12 Poles

1. Polish Presence in Colonial America

1 As with certain other European ethnic groups introduced in this book, a handful of Poles, perhaps six, were attracted to Jamestown, the first permanent English colony in North America. There is historical evidence, for instance, that Captain John Smith, in preparation for the Jametown venture, sought to recruit Polish artisans with various specialties, including glass blowing, pitch and tar making, soap making and lumbering.[1] Somewhat later, between the late 1600s and early 1700s, a group of Polish Protestants joined William Penn’s Pennsylvania colony.

2 When the American Revolution broke out, “about a hundred Poles with military experience came to participate in a fight for freedom,” an idea “that inspired many European liberals and revolutionaries” of the time. The two most well-known Poles were both recruited by Benjamin Franklin in Paris. They were Count Kazimierz (Casimir) Pulaski, a cavalryman, and Tadeusz Kósciuszko, a military engineer.[2] Some accounts credit Pulaski as “father of the American cavalry” for his contributions to cavalry tactics and discipline.[3] Kósciuszko planned and supervised the building of many forts and fortifications for the Continental army, including those at West Point, New York.[4]

3 Other early Polish immigrants to the U.S. included refugees fleeing failed rebellions in the homeland. Otherwise, until the 1870s, Poles came to the United States only in small numbers “as individuals or in small family groups, and they quickly assimilated and did not form separate communities, with the exception of Panna Maria, Texas,” situated southeast of San Antonio. Established by German Poles from Silesia in 1854, Panna Maria is the oldest Polish settlement in the United States.[5]

2. The Rise and Fall of Poland

1 According to John Bukowczyk, Poland in the 1500s was “[t]he largest and perhaps the most powerful state in Europe,” standing in the way of “tsarist, Tartar, and Turkish incursions” into the heart of Europe.[6] The Kingdom of Poland had first emerged in 1025 during the High Middle Ages, and in 1569 it had forged an alliance with Lithuania to form the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.[7]

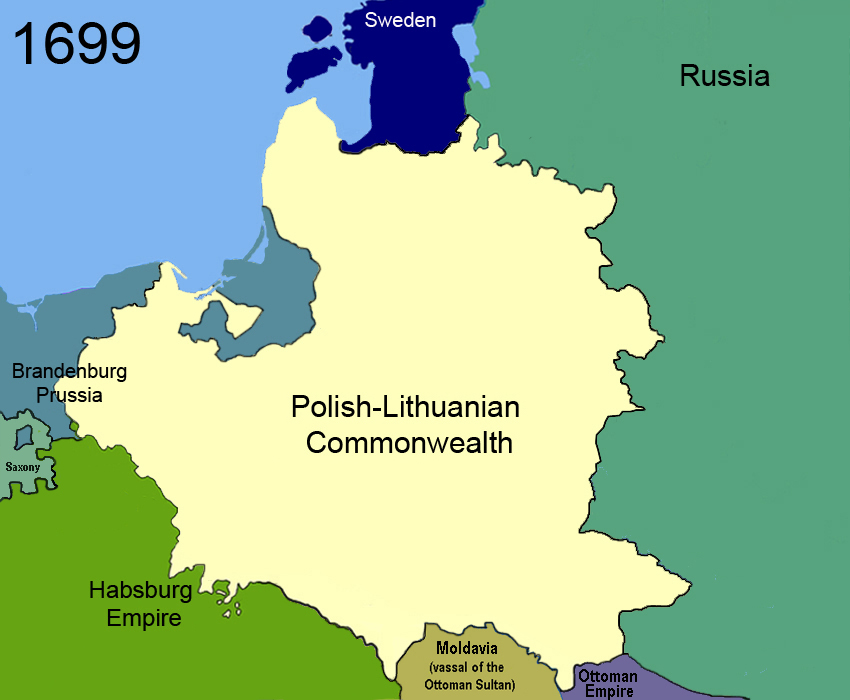

2 But by 1699, the Commonwealth found itself trying to fend off the encroachments of powerful neighbors, notably Prussia, the Habsburg Empire (which comprised Austria and other territories), and Russia. As the series of maps above illustrates, the Prussians, Habsburgs, and Russians carved off increasingly larger pieces of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1772 and 1793, finally partitioning it entirely amongst themselves in 1795.[8] Although the Polish people engaged in numerous armed uprisings in response to foreign rule, these all ended in failure, and Poland ceased to exist as an independent state.[9] Ethnic Poles in effect became stateless, which would subsequently make it difficult for immigration officials to accurately account for them, as we shall soon see.

3. Polish Mass Migration

1 From about 1870 to 1930, Poles were among several of the largest groups of new immigrants bound for the United States. However, because of the dissolution of Poland, historians have had a difficult time determining with confidence the true extent of Polish immigration, as many Poles may have initially been counted as Austrians, Germans, or Russians depending upon which occupied sector of the old Polish homeland they were coming from. Nevertheless, in 1900, the U.S. Census began asking respondents about their mother tongue, and many Polish speakers previously misidentified at the time of immigration could subsequently be counted as Polish, thus providing a more accurate estimate of Polish immigration. According to Daniels, “from two to two-and-a-half million ethnic Polish immigrants” came during the peak years before the U.S. clamped down on immigration in the 1920s, “of whom perhaps one-third returned to Poland.”[10]

2 At any rate, Polish mass migration to America took place in three phases, each with its own time frame and regional dynamics. Poles from German-held territories were the first to emigrate, followed by Austrian Poles (Galicians) and finally Russian Poles.[11]

3 German Poles had actually begun emigrating in the 1850s. A diverse group, they included artisans, intellectuals, children of the lower aristocracy, and farmers. The vast majority, perhaps 87 percent, arrived before the end of the century. In the middle of this wave of emigration, the process of German unification occurred wherein various German-speaking states, including Prussia, came together to form the German Empire. Unfortunately, while German unification may have been good for Germany, it worsened the hardships already faced by German Poles. Economic disruptions, including land reform that favored German landowners, meant that Polish landowners often lost their lands. Coupled with the general lack of other economic opportunities, this left many German Poles with little choice but to emigrate in search of better prospects.[12]

4 German Poles who came before the 1880s generally came as families and “took up farming because they arrived when land in the West was still cheap, they possessed enough money to buy it, and, as they considered themselves permanent settlers, they wanted to put down roots in America.”[13] On the other hand, the circumstances for Austrian and Russian Poles, who came later, were quite different. By the time they arrived in great numbers, land prices were much higher, and most newcomers lacked the financial means to acquire land. Besides, many saw themselves only as sojourners looking to make some money and return home.[14]

5 The second wave of Polish migration from 1890 to 1914 consisted of Poles from Austrian-held Galicia. This group comprised mostly peasants and day laborers. Finally, as a predominantly 20th-century event came the third wave consisting mainly of Russian Poles, mostly small land holders and agricultural wage laborers.[15]

6 From the 1870s to the 1930s, Polish immigrants gravitated mostly to major cities such as Chicago, Milwaukee, Buffalo, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and Detroit, or to smaller industrial areas in the East, North, or Midwest. These were well-thought-out choices, representing places where Poles might be best able to compete for jobs. Polish immigrants tended to avoid Cincinnati and St. Louis, where by the early 1900s, African Americans were meeting the demand for unskilled labor. Similarly, they bypassed Boston and Philadelphia, where light industry jobs required a level of skill and qualifications that Polish immigrants did not possess. By state, Illinois, Wisconsin, Ohio, Michigan, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Minnesota attracted the greatest concentration of Poles, providing work in various industries, including mining, quarrying, manufacturing, and textiles, and where unskilled labor was in constant demand.[16]

4. Working Lives of Polish Immigrants

1 Landing in U.S. during the decades of a rapidly growing industrial economy, these particular waves of immigrants—primarily young, single, and male—joined a growing work force of both native-born and various other ethnic groups, heading off into the mines and factories. Because industrialists had distinct notions about the supposed characteristics of various ethnic groups, Poles often found themselves pigeonholed as most suitable for heavy industrial work. They were stereotyped, for instance, as being more robust than Italians and as possessing other “desirable” qualities; employers believed Poles to be submissive, easily disciplined, and willing to “work long hours and overtime” without complaint.[17]

2 But Polish workers were actually guided very much by their own preferences, often grounded in Polish customs. Austrian and Russian men, for instance, avoided work in the “needle trades,” which they regarded as “women’s work.” And they weren’t afraid of “dirty, hard, and dangerous jobs,” such mining and factory work. As Bukowczyk has noted: “[t]hey soon found that the worse the job, the greater the opportunity.”[18]

3 In the U.S., Polish immigrant women made a more direct contribution to the household than they had in the home country. They often worked outside the home at domestic service or light manufacturing, at least until the first child was born, after which they usually followed the Polish cultural norm of staying at home as full-time mothers and homemakers. (This contrasted with the tendency of Italian women, who often continued to work long after marriage.) However, even when they took up full-time domestic roles, Polish women often still earned money. For instance, they often collected a fee from boarders for services rendered in laundering clothes, cooking meals, etc. Moreover, as happened with other immigrant working-class minorities, Polish women’s authority in the household tended to rise in the American context, changing the basic gender roles that had existed in the home country and sometimes contributing to domestic conflict.[19]

5. Polonia in America

5.1 Immigrant Generation

1 The term Polonia was often used by the Polish-language press in the late 19th century to describe “the imagined community of all Polish-speaking immigrants in the United States.” The term could also be used as a qualifier to refer to the Polish-speaking community living in any particular local area, such as a big city, so that one could refer to “Chicago Polonia, Buffalo Polonia, or Milwaukee Polonia.” Of course, ethnic identity is not a static entity but an idea that changes as a peoples’ idea of themselves changes in accordance with the historical and social conditions of the times; therefore, Polonia was an ever-evolving conception—different in the late 19th century from what it would be in mid-20th century.[20]

2 At any rate, as hundreds of thousands of Poles settled in groups in the northeastern United States in the late 19th century, they created a distinct cultural presence, preserving many of the cultural values of the Polish peasantry from Stary Kraj (i.e., the old homeland). One of the most important cultural values they brought with them was their Catholic faith. The earliest Polish settlers usually attended Irish and German Catholic parishes until they were able to establish their own, but once they did, the parish became the pillar of the Polish community, providing a site not only for religious activity but also for social activity.[21]

3 Once the local parish was established, a parish school often followed. Parish schools generally provided education only through the six or eighth grade. Classes were taught in Polish and the curriculum was heavy on religion and Polish history with English taught as a foreign language. After the establishment of the parish and the school, the next priority was to put in place “a comprehensive system of secular organizations to address various community and individual needs.”[22]

4 As for family life in American Polonia, it closely mirrored that in rural Poland. The foundation of family life was the extended family, with the eldest male as its acknowledged leader. Although each family member was entitled to personal respect, overall, the needs of the family took precedence over individual needs. The honor of the family was of utmost importance, and good behavior in the community was enforced through “peer pressure, the threat of gossip, and religious proscriptions enforced by the local parish priest.” Separation and divorce, forbidden by the Catholic Church, ensured stable family structures.

5 Because in America, “most families could not exist on the income of a single wage earner,” whenever possible, everyone in the household had to work. Adult males worked outside the home, while women managed the household. Women were often responsible for managing the family budget, and the father and children were expected to turn over their pay. Women often tended a family garden, “using the produce to supplement the family diet or to sell or barter outside the home.” As one immigrant explained:

… if your wife was thrifty, she baked at home, kept chickens in the garden, sewed for the children—you did not spend too much then because everything was so cheap—if you had other people working in the family and you did not drink in bars and saved your money, you could get somewhere like buy a house.[23]

6 While the family was the primary unit of social identification in Polonia, beyond that, the okolica, or neighborhood, was the center of social life. Especially in big cities, Polish neighborhoods could be thought of as both segregated and decentralized. They were segregated in the sense that Poles tended to cluster together in specific areas of the city. But they were decentralized in the sense that a city would typically have a number of different Polish wards dispersed around the city in areas that were not necessarily contiguous.[24]

7 Traditional Polish American values generally revolved around “security, stability, order and respectability” more than “progress.” Living in segregated ethnic communities enabled Poles to recognize these values while protecting themselves from overt discrimination by non-Poles and at the same time providing avenues for success within the ethnic neighborhood “based on the rural culture of their origin—being active in the church and community, holding leadership positions in organizations, and owning their own home.” The downside was that it “retarded immigrant acculturation into American life.” It was unnecessary, for instance, even to learn English “unless one aspired to move beyond the ethnic community.”[25]

8 Social status was very important in Polonia. In Stary Kraj, there had been a direct relationship between social status and land ownership. In America, home ownership took the place of land ownership as the primary source of social prestige, and American Poles strove hard to achieve it—with great success, as it turned out, compared to other ethnic groups. In 1930, for example, 70% of Poles owned their own homes, compared to 63% of Czechs, 25% of Yugoslavs, and about 33% of English and Irish. Surveys of home ownership in other cities across the East have revealed similar patterns. Similarly, whereas in Poland, status had been measured by the number of cows one owned and the size and quality of one’s farm buildings, in America these measures came to be replaced by family affluence and leadership in community organizations.[26]

9 Finally, Polonia was characterized by a well-defined status structure. At the top were the ethnic merchants who constituted a sort of wealthy upper class. Next came the skilled workers and owners of small businesses whose income was less than that of the larger merchants, while at the bottom were the unskilled workers, miners, and day laborers. In short, as James Pula has observed, “the average Polish American community of the immigrant generation was thus focused on Old World institutions … providing for the needs of their members through means compatible with both their European heritage and the demands of the urban American environment.”[27]

5.2 Second and Third Generation Polonia

1 In the 1920s, Polish Americans began, for the first time, to be employed in large numbers outside of urban Polonia. Otherwise, “many were becoming small business operators in their ethnic communities.” Leadership was in the process of being passed from the immigrant generation to their second-generation offspring. At the same time, the imposition of nationality quotas by Congress in 1921 and again in 1924 led to a sharp reduction in the influx of new Polish immigrants from 100,000 per year before 1921, to just less than 31,000 in 1921 and a bare 5,982 in 1924.[28]

2 One world event that brought a new dynamic to Polonia was the re-creation after World War I of an independent Poland. Several new developments emerged out of this. First, many Poles in the United States decided to return. However, Poles returning to a romanticized Poland were often disappointed, finding life in Stary Kraj unsatisfactory, and as many as 20,000 ended up re-immigrating to America. Meanwhile, in American Polonia, the nationalistic concern for the pre-World War I partitioned homeland that had united American Poles for so long largely disappeared. The result was a reorientation of American Polonia “away from a focus on European affairs to a more domestic focus on issues of concern to Poles in America. … Polish business and professional enterprises flourished and a genuine Polish middle class developed in virtually every ethnic community of any size.”[29]

3 As the second and third generations grew to maturity, signs of assimilation became unmistakable. “Athletic teams, social clubs, business and professional organizations, neighborhood groups, and youth clubs supplemented, or even replaced, the organizations founded during the immigrant generation.” Polish-language newspapers complained about the lack of cultural awareness among Polish youth. Polish radio programs began playing non-Polish music, and traditional Polish religious and folk music began to be reserved just for holidays. Polonia had begun to “Americanize.” Conflict between generations increased steadily as the traditions and perspectives of immigrant parents were reshaped or discarded by their children and grandchildren. Young Polish Americans often moved out of the ethnic ghettos, sometimes even anglicizing their names.[30]

* * *

4 After the euphoria that had enveloped the Polish American community following the reconstitution of Poland after World War I, the unfolding events of World War II twenty years later came as a terrible blow. When Nazi tanks rolled into Poland in 1939, Polish Americans reacted to the news with shock and outrage. As isolationist Americans began lobbying immediately against U.S. involvement, Polish Americans strongly opposed them, supporting the programs of the Roosevelt Administration to render financial and material support to England and its allies. After the U.S. entry into the war, Polish Americans also enlisted in the armed forces in large numbers, worked in defense-related industries, and purchased government bonds to finance the war.[31]

5 Although Polish Americans had largely supported the presidential administration of Franklin Roosevelt, many felt deeply betrayed by the capitulations of Roosevelt and Winston Churchill to the Soviet dictator, Joseph Stalin, in negotiations over the post-World War II Polish borders, which in effect had allowed Stalin to determine the borders and political landscape of the region. For Polish Americans, this was a grave concern, as it meant that Poland’s post-war fate was heavily influenced by the Soviet Union. They felt that the Western Allies had failed to protect Poland’s sovereignty despite the sacrifices made by the Polish people during the war. As a result, many Polish Americans, who had traditionally supported the Democratic Party, began to reevaluate their political allegiances.[32] Some abandoned the Democratic Party, and it would be nearly twenty years before Polish Americans would regain their previous enthusiasm for the party, in the 1960s.

6. Post–World War II Exodus from Poland

1 World War II had a significant impact on Polish American identity, changing the social composition and organizational structures of Polonia. First, the war drove a generation of Polish intellectuals out of Poland—many of them Jews who were fleeing from Nazi persecution. This influx of “internationally renowned, Polish-born intelligentsia not steeped in Polish-American political battles nor in Polish-American social and cultural life” introduced a decidedly new cultural dimension to the Polish American community. Furthermore, over a quarter of a million Poles had served in the Polish military (the third largest contingent under Supreme Allied Command after the Americans and British), and after the war many of them entered the U.S. as displaced persons.[33]

2 Assimilation into American society presented challenges for displaced persons, who grappled with trauma, cultural adjustments, and the need to start anew in a foreign country. Even when displaced persons might have tried to assimilate into the existing Polish American community, there was bound to be friction due to cultural, social, and educational differences between the newcomers and the long-established Polish Americans.[34] “Polish displaced persons with working-class, artisanal, and farming backgrounds integrated easily into blue-collar Polish America.” On the other hand, “middle class refugees fitted no better in Polonia than they did in mainstream American society.”[35]

3 Displaced Poles in the educated classes tended to resent the way older Polish Americans condescendingly referred to them as, “Biedaki,” (poor souls). On the other hand, Polish Americans found the educated Poles arrogant. They seemed not to hide their disdain for Polish Americans as people who worked “like peasants,” were “completely uneducated,” and “completely divorced from Polish culture.” The more educated newcomers seemed to think that they could automatically “assume the traditional class roles that persons of their position had held in prewar Poland and were dismayed to find a ‘lack of respect for educated people’ among Polish-Americans.” Moreover, they were shocked “at the poor Polish spoken by Polish Americans.” Others were horrified to discover that the Polish Americans were “already American.”[36]

7. Erosion of Polish American Identity

1 In the post-war years, Polonia was reshaped by economic and demographic forces. In fact, the very idea of a cohesive Polonia was called into question. By the 1960s and 1970s, it was no longer possible to define the “typical” Polish American family. The typical Polish immigrant family of 1910—with five children, living in the factory district of an industrial city, supported by “the man of the house” working a blue-collar job—was a distant memory. Many second-generation Polish Americans had moved to the suburbs, where they had only two or three children, but possibly two wage-earners, and were living much as many other Americans lived. Meanwhile, some second-generation, working-class Polish Americans had remained in Polonia’s aging urban neighborhoods, doing things much as they always had, but now alongside Black and Hispanic families that had been moving into traditionally Polish neighborhoods in increasing numbers. There might also be Polish displaced persons and their offspring who had entered the country after WWII, who differed markedly from the Polish American descendants of the first immigrants that had come a century earlier.[37]

2 Moreover, by the 1960s, the presence of immigrants in the United States as a percentage of the total population had reached its lowest level in fifty years, and the decades long campaign to “Americanize” immigrants had led to considerable homogenization and the erosion of ethnic identity among many Americans of European ancestry, Polish Americans included.

3 Other factors, like intermarriage with non-Polish spouses, as well as the considerable intermixing of various groups in American defense plants and military units during the Second World War, had also contributed. But as Bukowczyk has observed, Polish Americans were well aware “that their position in postwar America remained structurally separate from the mainstream. Thirty-thousand young Polish Americans,” Bukowczyk notes, “gave their lives during the Second World War. Yet returning servicemen … recalled being passed over for promotion because of their ‘unpronounceable’ surnames.” As a result, Polish Americans sometimes changed their names.[38]

4 American mass culture also treated Polish Americans with disrespect. According to Bukowczyk, “postwar mass culture absorbed none of the positive elements of Polish-American culture” as it had, for example, with respect to its depiction of Jewish and Black characters. Polish American characters to whom blue-collar ethnic viewers and their children could relate seemed, by comparison, completely absent. Instead, Polish Americans often encountered anti-Polish stereotypes, just one notable example being Marlon Brando’s portrayal of Stanley Kowalski in “A Streetcar Named Desire.”[39]

5 Another disconcerting indignity often faced by Polish Americans during this era was the ubiquitous circulation of “Polak jokes,” which generally portrayed Polish people as dim-witted and bumbling but otherwise harmless. Such jokes not only circulated widely in the general population but were prominently featured on network television. Ironically, by the 1980s, “sensitivity to racism … did not cause Americans to reject anti-Polish bigotry,” as joke-tellers began recycling jokes that had once been “colored” or “Black” jokes,[40] as if an unacceptable disparagement of one group became strangely acceptable when aimed at another.

6 As Bukowczyk has complained:

Though many Polish-Americans—conductors Stanislaw Skrowaczewski and Leopold Stokowski (himself half-Polish, half-Irish), sculptors Richard Stankiewicz and Janusz Korczak-Ziolkowski, artists Richard Anuszkiewicz and Karol Kozlowski, inventor Tadeusz Sendzimir, and biochemist Hilary Koprowski—have made substantial achievements in postwar America, their success has gone largely unnoticed and has done little to neutralize the anti-Polish stereotypes so prevalent in American mass culture.[41]

7 It is perhaps understandable why Polish Americans may have wished to disavow or downplay their ethnic heritage, and yet, the 1970s would usher in an unexpected era of ethnic revival.

8. Revival

1 Suddenly, in the 1970s, a broad-based ethnic revival was sweeping Polish America and other ethnic enclaves as well. Before it peaked in the 1980s, it initiated a reappraisal of immigrant culture and its place in the American tapestry. It began just as the percentage of Polish Americans attending college increased dramatically, with new branches of state universities opening in industrial cities where high concentrations of Polish Americans resided, including Chicago, Milwaukee, Detroit, and Buffalo. By keeping tuition low, government aid began providing educational opportunities for the children of blue-collar workers previously unable to afford a university education.[42]

2 But the interest of the new generation in ethnic issues came as a surprise to many sociologists. Moreover, as Mary Cygan has observed, to a generation “exposed to the cultural storms shaking American universities in the 1960s and 1970s,” the problem of ethnic identity required a more radical approach than the genteel critique offered in the interwar years by Polish culture clubs. “Like their peers,” says Cygan,

… this generation of Polish American students was suspicious of what seemed to them to be middle-class, homogenized, corporate-centered culture, yet undergraduates from working-class families often felt alienated from the middle-class youth culture as well. Absorbing arguments of the civil rights movement, some of them began to talk of Polonia as a minority community. Stressing the blue-collar dimension of Polonia culture, they advanced an identity that acknowledged class distinctions [which had become] blurred by the [growing tendency of ethnic Europeans to identify merely as] white. Like African American youth at the time, they [i.e., Polish Americas] looked for an alternative lifestyle grounded in an ethnic culture.[43]

3 According to Bukowczyk, as “second-generation Polish Americans … fled from their backgrounds, … third-and fourth-generation Poles rediscovered theirs.” In 1972, “1.1 million more persons identified themselves as Polish-Americans,” according to the U.S. Census Bureau, “than had done so a mere three years earlier.” There was also “a surge of interest in Polish history, folklore, and culture,” and some Polish Americans even began reclaiming their surnames, as exemplified by the “Warren, Michigan, politician named Jacob returning to Jakubowski or the Detroit television news reporter bravely changing his name, Conrad, back to Korzeniowski.”[44]

4 On the other hand, third- and fourth-generation Polish Americans could be quite selective in their embrace of ethnic identity, consciously deciding what to accept or discard. Some became part-time ethnics, fully Polish at the Polish bar, restaurant, film or cultural festival, yet otherwise indistinguishable from other Americans in daily life. Others might pursue “professional careers related to their ethnicity, working as linguists, translators, librarians, politicians, or historians,” while not displaying other overtly ethnic characteristics. Then, there were those of mixed backgrounds, who might embrace multiple identities, choosing to affiliate with one or another parent’s ethnicity or alternating between them based according to the situation. “A young Polish/Italian-American, for example, might be Polish on Pulaski Day and Italian at the Saint Gennaro festival.”[45]

9. Is There Still a Polonia?

1 Since the 1970s, the status of Polish Americans has benefited from the notoriety achieved by many prominent Polish Americans, including political figures who rose to prominence in the 60s and 70s, like politicians Edmund Muskie and Zbigniew Brzezinski (Secretary of State and National Security Advisor respectively under President Jimmy Carter) Leon Jaworski (Special Prosecutor during the Watergate scandal), and Barbara Mikulski (who served Maryland for 10 years as a Representative and 30 years as a Senator).

Politicians: Edmund Muskie, Zbigniew Brzezinski, Leon Jaworski, Barbara Mikulski

2 Then there were the accomplishments in high culture during the 70s and 80s—movie directors like Roman Polanski and Andrzej Wajda, philosopher Leszek Kolakowski, novelist Jerzy Kosinski, and poet Czesław Miłosz, who received the Nobel Prize in 1980. Achievements such as these and others enhanced Americans’ perception of the Polish American community.[46]

Movie directors: Roman Polanski & Andrzej Wajda; Philosopher: Leszek Kolakowski;

Novelist: Jersey Kosinski; Poet: Czesław Miłosz

3 Yet whether the notion of Polonia still serves a useful function remains an open question today for scholars of Polish American history and culture. Cygan, Bukowczyk, and Pula all lean towards yes, but it is an ambiguous yes. What seems clear is that whatever Polonia is today, “it is not,” in Pula’s words “the Polonia of 1900 or even 1950. What is unclear is whether there will be any recognizable form of Polonia a century hence.” There was little doubt in Pula’s opinion that Polonia was in decline already in 1995, when the traditionally Polish neighborhoods of Saint Mark’s Place and the Lower Eastside had lost their ethnic character, with, among other changes, the “Dom Polsky” (Polish Community Center) first becoming a nightclub and then an American community center.[47]

10. Where Polish Americans Live Today

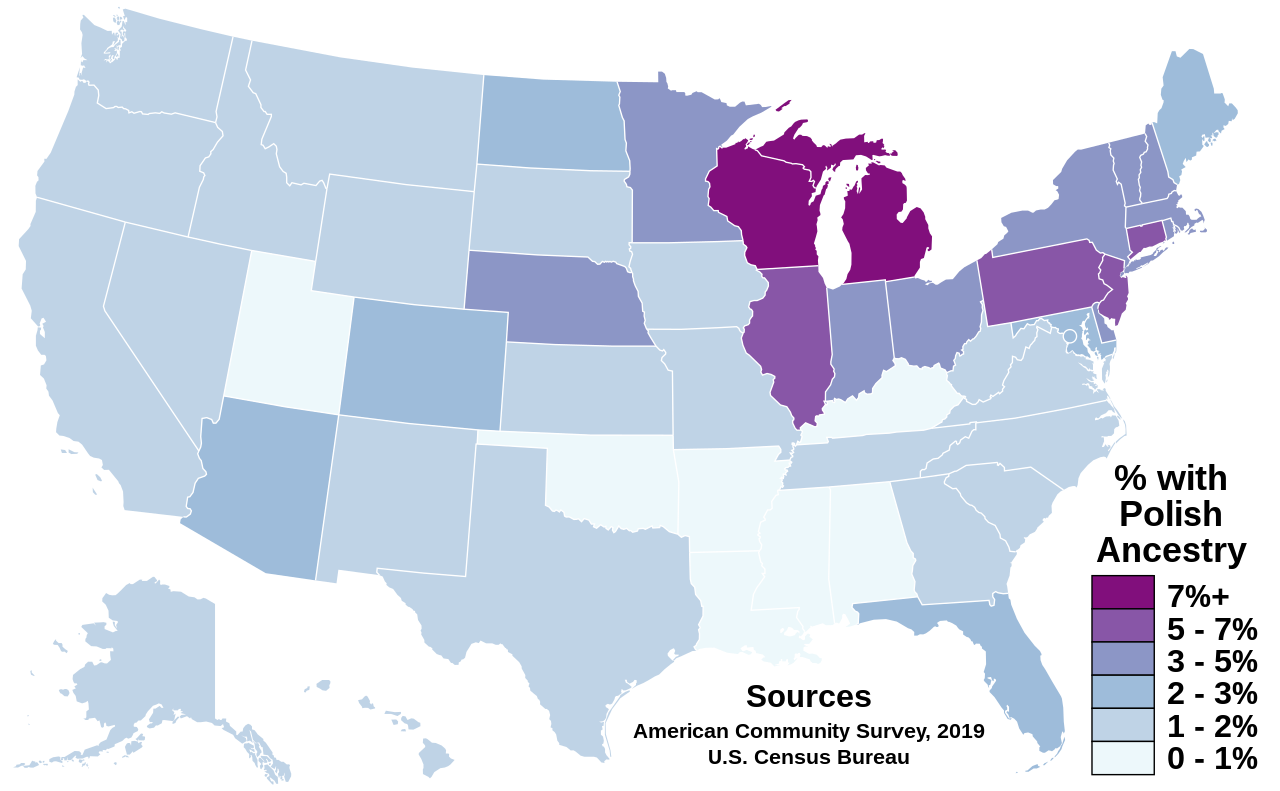

1 Americans with Polish ancestry can be found in every part of the country today, but the highest concentrations live for the most part in the regions bordering on the Great Lakes and in the Northeast.

Chapter 11 Study Guide/Discussion Questions

Activity 11.1

Based on your understanding of subsections 1–3, answer and discuss the following questions with one or more fellow readers.

1. What role did Poles play in colonial America?

2. Describe the misfortune that befell Poland in the 18th century.

3. Create a table like the one below to describe the characteristics of Polish migration in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

| Time Frame | Territorial Origins | Occupations of Migrants | Reasons for Emigrating |

| 1850s–1880s

|

|||

| 1890s–1914

|

|||

| 20th-century

|

Activity 11.2

Based on your understanding of subsections 4–5, answer and discuss the following questions with one or more fellow readers.

- Explain how stereotypes and cultural preferences shaped the experiences of Polish immigrants in the U.S. during the industrial era.

- Describe how the immigrant experience altered gender roles in Polish American families.

- To what does the term “Polonia” refer? Explain the significance of each of the following values associated with the idea of “Polonia:” (Catholicism, the local parish, family dynamics, division of labor, “okolica,” traditional Polish values, determinants social status)

- Describe the changes that second and third generation Polish Americans introduced into Polonia.

Activity 11.3

Based on your understanding of subsections 6–9, answer and discuss the following questions with one or more fellow readers.

- Describe how the Second World War and its aftermath disrupted Polonia’s understanding of itself.

- Identify some of the factors that contributed to the erosion Polish American identity between the 1950s and the 1980s.

- Identify the factors that served to bolster Polish pride during the same time frame.

- What seems to be the status Polonia today?

Media Attributions

- Kazimierz Pułaski © Jan Styka is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Tadeusz Kościuszko © Karl Gottlieb Schweikart is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Poland, 1699 © Esemono is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Poland, 1772 © Esemono is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Poland, 1793 © Esemono is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Poland, 1795 © Esemono is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Polish Coal Miner © Marion Post Wolcott is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Basilica of Saint Josaphat © Sulfur/James Steakley is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Polish Village © Unknown/Asehn is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Houses in Polish District, Detroit, Michigan © John Vachon is licensed under a Public Domain license

- War Relief to Poland © Detroit News Staff is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license. Used with permission under Fair Use

- Polish Museum, Chicago © Antonio Vernon, (TonyTheTiger at en.wikipedia) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Gallery Images – Prominent Polish Americans in Government

- Edmund Muskie © Bettmann Archives is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Zbigniew Brzezinski © Jack E. Kightlinger is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Leon Jaworski © Bernard Gotfryd is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Barbara Mikulski © US Senate is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Gallery Images – Polish Americans in the Film, Literature, and Philosophy

- Roman Polanski © Georges Biard is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Andrzej Wajda © Anonymous is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Leszek Kolakowski © Bert Verhoeff is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Jerzy Kosinski © Rob Mieremet is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Czeslaw Milosz © Artur Pawłowski is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Americans with Polish Ancestry by state © Abbasi786786 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Wikipedia contributors, "Jamestown Polish craftsmen," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed July 21, 2023). ↵

- Daniels, Coming to America, 218–219. ↵

- Wikipedia contributors, "Casimir Pulaski," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed July 21, 2023). ↵

- Wikipedia contributors, "Tadeusz Kościuszko," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed July 21, 2023). ↵

- Daniels, 219; Wikipedia contributors, "Polish Americans," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed July 21, 2023); Wikipedia contributors, "Panna Maria, Texas," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed July 21, 2023). ↵

- John J. Bukowczyk, A History of the Polish Americans, (New York: Rutledge, 2008), 1. ↵

- Wikipedia contributors, "Poland," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed July 22, 2023). ↵

- Wikipedia contributors, "Territorial evolution of Poland," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed July 22, 2023). ↵

- Bukowczyk, History of Polish Americans, 4–5. ↵

- Daniels, 219. ↵

- Bukowczyk, 11; Daniels, 219. ↵

- Bukowczyk, 6, 11; Daniels, 219. ↵

- Bukowczyk, 20. ↵

- Bukowczyk, 20–21, 23. ↵

- Bukowczyk, 11–12; Daniels, 219. ↵

- Bukowczyk, 51–52. ↵

- Bukowczyk, 21. ↵

- Bukowczyk, 21–22. ↵

- Bukowczyk, 25. ↵

- Mary E. Cygan, "Inventing Polonia: Notions of Polish American Identity, 1870–1990," Prospects, Vol 23, Oct. 1998, 209. ↵

- James S. Pula, Polish Americans: An Ethnic Community, (New York: Twayne Publishers, 1995), 20-21. ↵

- James S. Pula, Polish Americans, 21. ↵

- Pula, 24–25. ↵

- Pula, 23. ↵

- Pula, 23–24. ↵

- Pula, 27–29. ↵

- Pula, 29. ↵

- Pula, 67. ↵

- Pula, 69; 73. ↵

- Pula, 79–81. ↵

- Pula, 84–87. ↵

- Bukowczyk, 90–92. ↵

- Bukowczyk, 92–93. ↵

- Bukowczyk, 92–93. ↵

- Bukowczyk, 95. ↵

- Bukowczyk, 95–96. ↵

- Bukowczyk, 103. ↵

- Bukowczyk, 106–107. ↵

- Bukowczyk, 112. ↵

- Bukowczyk, 112–113. ↵

- Bukowczyk, 113. ↵

- Cygan, "Inventing Polonia," 234. ↵

- Cygan, 234. ↵

- Bukowczyk, 119. ↵

- Bukowczyk, 120. ↵

- Bukowczyk, 121. ↵

- Pula, 145. ↵