8 Italians

1. Early Italian Presence in the Americas

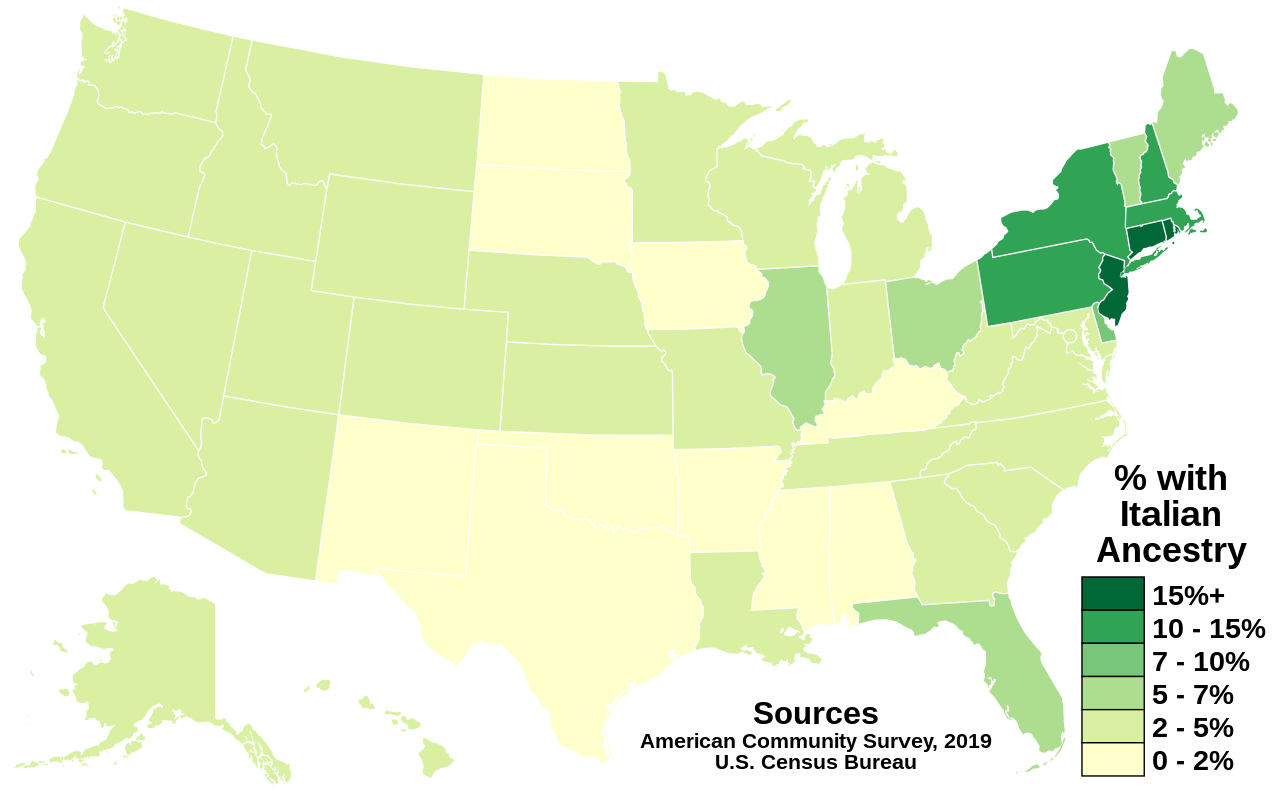

1 According to immigration historian Roger Daniels, “no other ethnic group in American history” immigrated in such large numbers in so short a time as did the Italians; more than 4.1 million Italians entered the U.S. between 1880 and 1920. Curiously enough, “Italians, like the Chinese, had a strong migratory tradition,” and Italians had emigrated to a wide variety of destinations outside of Europe, including to North Africa and South America. But prior to the late 1800s, only a scattered few thousand Italians had come to North America.[1]

2 And yet, the few who came did leave an impression. In his book Coming to America, Daniels runs through a list of notable Italians starting with Cristoforo Colombo (Christopher Columbus). Then there was Amerigo Vespucci from Florence, after whom the Americas were named. Vespucci explored the coast of South America, but he never made it to North America. A Venetian, Giovanni Caboto, was the first European to explore the New England coast, although students of American history often mistake Caboto as an Englishman because of the anglicized spelling of his name (John Cabot) that often appears in English-language accounts. And another Florentine, Giovanni da Verrazzano, was the first European to sail into New York Harbor. These Italian explorers, however, were all working on behalf of other European powers—Colombo for Spain, Vespucci for Spain and later for Portugal, Caboto for England, and Verrazzano for France.[2]

3 In addition to these Italian sea captains, Italian soldiers accompanied the Spaniard De Soto on his trek across the South and into the Southwest as well as the Frenchman La Salle on his forays around the Great Lakes and down the Mississippi River. And Italian priests were among the first Catholic mission fathers to establish settlements in the Southwest when it was still part of the Kingdom of New Spain. “All told several hundred Italians participated in the exploration and conquest of North America.”[3]

4 There were Italians present in the British colonial era and throughout the U.S. national era as well. For example, as early as 1622, there were several Venetian glassblowers in Jamestown. In 1656, a community of more than a hundred Waldensians (Italian Protestants) settled in the Dutch colonies of New York and Delaware. And when Thomas Jefferson built Monticello—his plantation home near Charlottesville, Virginia—he recruited Italian stonemasons to help. Later, after he had become president, Jefferson recruited Italian musicians to form the core of the first United States Marine Band. During the American War of Independence, Italian soldiers served in the revolutionary armies, and a wealthy Italian fur trader, Giuseppe Maria Francesco Vigo, provided provisions and crucial wartime intelligence to American military leader George Rogers Clark, operating in the Western frontier in Illinois during the Revolutionary War. (Nearly a hundred years later, during the American Civil War, Italians could be found fighting on both sides.)[4]

5 Besides Jefferson’s bandsmen, Italian musicians and artists made other early contributions to the fledgling United States. For instance, Mozart’s librettist for the operas Don Giovanni and The Marriage of Figaro, an Italian named Lorenzo da Ponte, supervised the building of the first American opera house. Italian painters and sculptors also decorated the first U.S. Capitol as well as its successor, after the first one was burned by the British in 1814. Although “most of the Italians who came here [in the early- to mid-19th century] were artisans, merchants, businessmen, professional people, musicians, actors, and waiters,” some Italians engaged in hard labor as well. Italian stone cutters, for example, helped develop the granite quarries in Vermont (and formed one of the first Italian American trade unions). Italians mined coal near Scranton, Pennsylvania, and Italians showed up to mine gold during the California Gold Rush in 1849. By the latter 19th century, small Italian communities could be found in cities as disparate as New York, San Francisco, and New Orleans.[5]

2. First Great Italian Influx

1 Italian immigration to the U.S. remained relatively sparse until 1880, when the first major wave of Italian immigration began, largely precipitated by the Italian Unification which had taken place twenty years earlier in 1861. Prior to unification, Italy had been fragmented, much like the divided German states, consisting of various small regions all under separate rule. With the consolidation of the various states of the Italian Peninsula and its outlying isles into a single state came economic and social disruptions. Northern regions enjoyed greater economic development and became more industrialized and prosperous, while the South remained largely agrarian and underdeveloped. Driven by poverty and lack of economic opportunity, young Italians, particularly in the south of Italy, sought better prospects by migrating. From 1880 to 1914, 13 million Italians migrated out of Italy; nearly one-third of them came to the U.S. in the quest for “bread and work.[6]

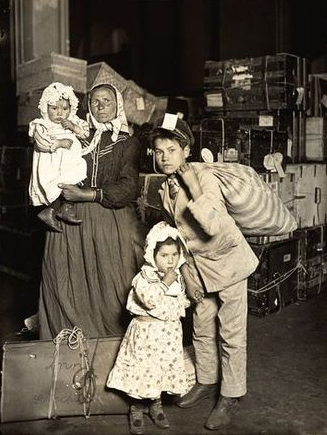

2 Two-thirds of the Italians who arrived at Ellis Island in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were contadini, landless peasants from the southern part of Italy, including from Sicily and Sardinia. At first, most of them were male, and they usually came, like the Chinese, with the intention only to make enough money to go back home and perhaps buy land. In fact, as many as 60% of Southern Italian migrants eventually did return home. At any rate, like the Irish before them, the Italians had no previous industrial experience, so their work prospects in America began with “a pick and shovel,” and they went to work “digging canals, paving street, installing gas lines, building bridges and skyscrapers, excavating tunnels and laying tracks.” According to Marcella Bencivenni, “[i]n 1890, nearly 90% of the laborers in New York Department of Public Works were Italian immigrants,” making it tempting to conclude that Italians virtually built modern-day New York City.[7]

3 Like the Irish and the Chinese, the Italians faced extreme prejudice from American employers who referred to them as “black labor.” Nor did Italian immigrants have any unwillingness to work with blacks, which no doubt reinforced the racist employers’ contempt for them. At the same time, labor organizers disliked the Italians, accusing them, along with the Chinese and the Irish, of “depressing wages and downgrading standards of living for American workers.”

4 Another challenge the first Italian immigrants confronted was the padrone system. Under this system, labor bosses, known as “padrones,” served as intermediaries between Italian workers and employers. The padrones recruited, transported, and supervised groups of Italian laborers, often serving as labor contractors. Italian immigrants, many of whom were unskilled and spoke little to no English, often relied on the padrones to secure employment and provide basic accommodations. However, the padrone system was is a double-edged sword. True, it often provided some measure of support, like helping the new immigrant find employment and promising a degree of job security in a new and challenging environment. On the other hand, padrones often charged high fees which came out of a worker’s earnings. They also exerted control over various aspects of workers’ lives, from living conditions to leisure activities, resulting in a form of indentured servitude. Moreover, the housing accommodations they provided were often overcrowded and substandard.[8]

5 Although the overwhelming majority of Italian immigrants worked at manual labor in the big cities of the East, not all did. Some went to San Francisco and worked as fishermen and stevedores. Others worked the coal mines of Kansas, Pennsylvania, Minnesota, Colorado and Michigan. Approximately 15 and 20 percent were skilled workers and artisans—barbers, tailors, bricklayers and stonemasons. The skilled workers and artisans also had higher rates of literacy, and some were steeped in radical ideas as far as politics and labor were concerned.[9]

6 A small minority of Italians made a living in farming, and some introduced new crops and new techniques, in some cases establishing agricultural empires. In the 1880s, for instance, “immigrants from Genoa, Turin, and Lombardy began to enter California’s then small grape-growing, winemaking industry.” One of the first California wineries to grow out of this development was the Italian-Swiss Colony vineyard in Asti, California. Meanwhile, farther south, two brothers named Joseph and Rosario Di Giorgio acquired 40,000 acres in California’s Central Valley and established “the Di Giorgio Fruit Corporation, which became the largest shipper of fresh fruit in the state.” (In the 20th century, the company gained a bad reputation as a notorious exploiter of labor and would eventually clash with Filipino and Chicano labor organizers.)[10] (See Chapter 2 for more on that.)

7 After 1900, more Italian immigrants began entering industrial jobs as machine operators. By that time, Italian women had also begun arriving in greater numbers and could be found working in the canning, garment, and cigar manufacturing industries. Some women also earned money by providing domestic services, including midwifery, boarding, cooking, and cleaning. Women with children often worked from home or in small tenement workshops doing embroidery, making lace, or doing small sewing jobs that paid by the piece. “By 1920, close to 80 percent of hand embroiderers in New York were Italian women who worked for the most part from home.”[11]

8 As Italian immigrants steadily adapted to their new American lives, their communities began to take on a distinctive character. The establishment of “Little Italies” mirrored the pattern seen in other ethnic neighborhoods like Klein Deutschland and Chinatown, where immigrants clustered together “in small enclaves along regional lines that replicated familiar social patterns, values and institutions.” These Little Italies became the epicenters of many emerging Italian American communities that offered Italian immigrants security and support in the face of the challenges they encountered daily in their adopted homeland. The close-knit neighborhoods also became hubs for Italian labor and political organizing, initially motivated by the discrimination that Italian immigrants faced from the mainstream American labor unions that sought to exclude them.[12]

3. Labor Organizing and Politics

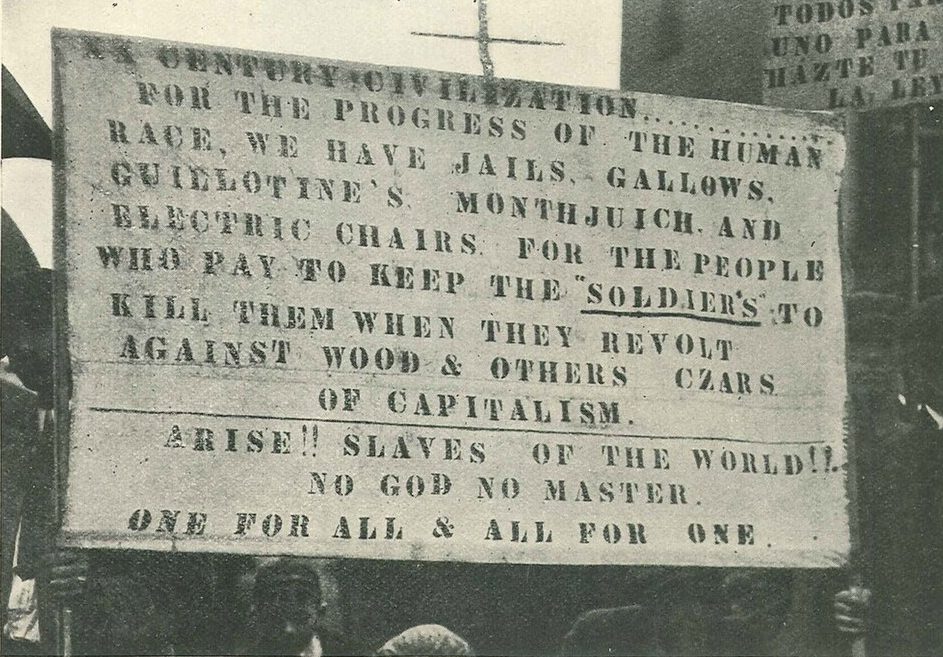

1 Ironically, American labor leaders considered Italian Americans to be unorganizable, but this was hardly the case. As Marcella Bencivenni has insisted, Italian immigrants were actively engaged in various forms of labor organizing “almost immediately upon arrival. Inspired by charismatic radical leaders or sovversivi (subversives)—as anarchists, socialists, syndicalists and communists were collectively known—Italian immigrants formed mutual aid societies, workers’ cooperatives, cultural organizations and trade unions.” According to Bencivenni:

The first consumers’ cooperative among Italians opened on Mulberry Street in lower Manhattan in 1879. More followed in the next years in radical strongholds such as Philadelphia, Paterson (New Jersey), Barre (Vermont), San Francisco, and Ybor City (Florida). Between 1882 and 1896 in New York City, Italian pastry cooks, barbers, garment workers, masons, shoe workers, musicians and woodworkers in New York City each established a mutual aid society affiliated with the Socialist Party, and similar ones were formed in other cities.[13]

2 Although some of the earliest organizing efforts were opposed by “local padroni” and other powerful, and for the most part corrupt, men “who controlled the political and social life of the Little Italies … eventually the Italian Socialist Federation established in 1902 was able to attain … organizational stability and unity, leading hundreds of thousands of Italians into the labor struggle.”[14]

3 When given the opportunity, Italians were willing to join American trade unions. The Knights of Labor—a fraternal organization that embraced all workers and promoted a wide variety of political reforms, including an eight-hour day work day, the abolition of child labor, and equal pay for equal work—was particularly attractive to Italian Americans. On the other hand, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) was less welcoming, creating many barriers to entry such as “prohibitively high initiation fees, apprenticeship requirements, and citizenship or naturalization papers.” While many skilled Italian workers did join the AFL, they often found themselves marginalized within the organization, and “they also found the culture and discipline of the AFL, which held meetings only in English, oppressive and alienating.[15]

4 The establishment of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in 1905 also played a pivotal role in shaping Italian American participation in the labor movement. Often referred to as the Wobblies, the IWW’s members adopted a radically inclusive approach to labor organizing, welcoming immigrants and unskilled laborers into its ranks without prejudice. Italian immigrants found the IWW’s message of solidarity and its commitment to social and economic justice appealing, making the IWW a prominent force in mobilizing Italian laborers and advancing their rights within the American labor movement.

5 According to Bencivenni:

… the Italians became the mainstay of industrial unionism, leading some of the most important IWW strikes in the northeast and also forging important multiethnic alliances. In San Francisco, for example, during the early 1910s they formed a Latin branch of the IWW with Hispanic and French radicals that propelled a series of labor agitations among the city’s bakers, cannery workers and salumieri (sausage makers). Similarly, in Ybor City, Florida, Italians organized with Cubans and Spaniards in the cigar factories, producing a distinct Latin radical subculture around commonly held values: working class solidarity, distrust of centralized power and anticlericalism.[16]

6 But the greatest contribution of the Italian Americans to the U.S. labor movement, according Bencivenni, was the historic strike that took place in Lawrence, Massachusetts in 1912, a strike that “lasted three months and ended with an historic victory for industrial workers and a congressional investigation of working conditions in the textile mills.” Of all the strikers, representing over twenty different nationalities, the Italians were the largest and most militant, “providing leadership … and strategies that drew on familiar homeland tactics,” but which were new within the U.S. context, namely the first moving picket line and the removal of children to other cities in order to ensure their safety during the strike.[17] Of course, the organized labor movement achieved many other successes and partial successes as well as some failures throughout the first decades of the 20th century.

Strikers sent their children out of town and then went to confront armed militia.

7 As the 1920s dawned, with American standards of living on the rise, Italian radicalism decreased, as did American radicalism in general. At the same time, immigrants witnessed the rise of anti-Communist hysteria following the Russian Revolution and a resurgence of nativism, and they watched with concern as the Ku Klux Klan began attacking immigrants. Many Italian workers thought it best to “quietly distance themselves from ‘un-American’ values and lifestyles.” On top of that, the new immigration quotas enacted in 1924 virtually ended Italian immigration, thereby depriving the labor movement of new members. During the 1930s, “the Great Depression temporarily revived Italian [American] efforts to ameliorate” the worst excesses of capitalism, but by then Italians no longer represented a distinctive labor movement; they had instead “become part of a multiethnic American working class.”[18]

* * *

8 In the realm of electoral politics, Italian Americans’ rise to prominence, as contrasted with that of the Irish Americans, was delayed by circumstances beyond their control. For one thing, compared to the Irish, the Italians were relative newcomers to the U.S. True, the Italians threw themselves into the political process right away, registering to vote, voting, campaigning for public offices, and getting elected locally, usually with the help fellow Italians. But unfortunately, the “Mafia” stereotype—i.e., the mistaken view that everyone of Italian descent was somehow connected to organized crime— hindered Italian Americans’ ascent to higher office, at least in the decades before the end of World War II.[19]

9 Like the Irish, most Italian Americans tended to support the Democratic Party because of its pro-working-class, pro-immigrant policies. Although they occasionally decided to punish the Democrats for a perceived betrayal, such as Democratic president Woodrow Wilson’s refusal to support Italian nationalists during the Paris Peace Conference in 1920, which prompted Italians to swing en masse to the Republicans, Italian American voters usually returned again to the Democratic fold.[20]

10 Blaming the Republican president Herbert Hoover for the Great Depression, Italian Americans voted overwhelmingly for Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932. The New Deal policies that the Roosevelt administration put in place largely benefited Italian Americans through its relief and recovery programs as well as its labor legislation, which guaranteed the rights to unionization and collective bargaining. Roosevelt further solidified Italian American support for the Democratic Party for the next several decades by backing Italian American candidates running for elected office and by appointing them to prominent positions within the administration.[21]

11 A few Italian American politicians, however, did succeed as Republicans in the period between the two world wars despite the dominance of the Democratic Party during the New Deal era. Notable examples include Angelo J. Rossi, a Republican who served as mayor of San Francisco from 1931 until 1944, and Fiorello La Guardia, mayor of New York from 1934 to 1945. La Guardia in particular, who was of mixed Italian and Jewish ancestry, was the first Italian American mayor of New York City and is widely regarded as perhaps the greatest mayor in that city’s history.[22]

4. The Strange Appeal of Benito Mussolini

1 In the wake off the radical Italian Labor movement, the response of Italian Americans to the rise of Benito Mussolini, the fascist dictator who governed Italy from 1922 to 1943, might seem somewhat paradoxical. Mussolini initially garnered overwhelming support among Italian Americans. But perhaps that support is less surprising in view of the fact that substantial segments of the wider American public also viewed Mussolini favorably during that era, with mainstream American publications such as The New York Times, the Plain Dealer (Cleveland), and the Washington Post even publishing articles singing his praises![23] The fact that the fascists were anti-communist might have played some role in the uncritical acceptance they enjoyed.

2 At any rate, the attraction that many Italian Americans felt towards Mussolini might be most easily understood as a compensatory move on the part of an ethnic group still struggling for full acceptance within American society. Indeed, as Stanislao Pugliese has observed:

Mussolini’s overheated rhetoric to the effect that contemporary Italians were the descendants of the ancient Romans and that modern Italy had been denied its rightful “place in the sun” … had a powerful attraction to Italians in America. …[E]migrants who had originally thought of themselves as Napoletani, Calabresi, Palermitani, etc., only began to think of themselves as Italians once they set foot in the New World. There, they were subject to prejudice, racism and stereotypes, sometimes fostered by an older generation of northern Italian immigrants. Political, legal and immigration authorities and the general culture accepted those negative and pernicious stereotypes. No wonder then that Fascism functioned as an ideology of compensation for the first and second generation of Italian immigrants.[24]

3 In any event, not all Italian Americans were fooled by the fascist propaganda. For instance, those in the Italian American labor movement who were steeped in principles of workers’ rights and social justice found Mussolini’s authoritarianism and suppression of labor rights deeply troubling and were not as easily deceived. And Italian American intellectuals, as well as their exiled Italian counterparts, were clearly aware of the threat that Mussolini posed to democratic freedoms.[25]

5. World War II Changed Everything

1 In the end, despite Benito Mussolini’s initial appeal among Italian Americans, World War II changed everything. Four days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, when Mussolini declared war on the United States as a Japanese ally, the reaction in Little Italies was one of “stunned silence, then tears and lamentation of ‘vergogna’ (shame), followed by pledges of loyalty to the United States.” Mussolini photos and Italian flags disappeared, replaced by portraits of FDR and small American flags. The Governor of New York, Charles Poletti, an Italian American, declared: “There has never been any doubt that Americans of Italian extraction are loyal and devoted to the principles of freedom and liberty on which America was founded. Thousands and thousands of young Italo-Americans have [already] volunteered in the Army and Navy of the United States.”[26]

2 Italian Americans suspected of having connections to Italian fascist organizations were interned. Similarly, Italian immigrants that had not become naturalized citizens faced curtailments to their freedoms, if not internment as “enemy aliens.” Otherwise, generally speaking, the wartime treatment of Italian Americans, like that of German Americans, was not as egregious as that of Japanese Americans, who were rounded up and interned in mass.

3 At the same time, Italian Americans made substantial contributions to U.S. military efforts during World War II. An estimated 1.5 million Italian Americans served in the armed forces in both the European and the Pacific theaters. An often-neglected chapter in the story of Italian American military service is that of their role in the operations of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor to the CIA. Italian Americans were valuable OSS operatives thanks to the language skills and cultural knowledge they brought to the organization.[27]

4 In short, World War II mobilized the entire U.S. population in an unprecedented effort, and Italian Americans joined Americans of all backgrounds as fellow employees in wartime industries, as well as volunteers in organizations dedicated to national service. According to Candeloro: “The World War II experience Americanized Italians and all the other ethnic groups in America. And it rewarded their efforts with social, economic, and cultural changes that integrated Italians into the mainstream and propelled them into the middle class.”[28]

6. Coming of Age Politically

1 In the wake of World War II, Italian Americans experienced a political coming of age. After the 1948 elections, for example, their representation in state legislatures doubled in the Northeast. In the same year, their influence also grew nationally, with eight Italian American candidates winning seats in the U.S. House of Representatives, whereas no more than four congressmen of Italian background had served in Washington in any previous year. The following year Carmine De Sapio assumed the leadership of Tammany Hall, breaking a long tradition of Irish control of that organization. In 1950, three of the candidates vying to be mayor of New York City were all of Italian ancestry. And the same year, John O. Pastore became the first Italian American to be elected to the U.S. Senate.[29]

2 In the following decades, Italian Americans would continue to distinguish themselves politically, serving in various governmental capacities at the local, state, and national levels, and achieving a number of firsts. For example, Mario Cuomo was the first Italian American to be elected Governor of New York, a position that he held from 1983 to 1994. Geraldine Ferraro made history in 1984 as the first Italian American as well as the first woman to ever be nominated for Vice President on a major party ticket. In 1986, Antonin Scalia became the first Italian American Supreme Court Justice. And Nancy Pelosi, who was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1987, became the first woman Speaker of the House in 2007, a position she held from 2007 to 2011 and again from 2019 to 2023.[30]

Government: Mario Cuomo, Geraldine Ferraro, Antonin Scalia, and Nancy Pelosi

7. Italian Americans and Popular Culture

7.1 Music

1 The influence of African Americans as the leading innovators in the history of American popular music is, of course, undeniable. However, perhaps no immigrant group rivaled the influence of Black musicians on the American musical scene in as big a way as the Italian Americans, beginning with Enrico Caruso. As John Gennari has explained, Caruso—an Italian opera singer who was born in Naples and emigrated to the United States—was “the first international pop star of the twentieth century.” He made his U.S. debut in 1903 at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. As surprising as it might seem today, opera had been a popular genre in 19th century America, enjoyed not just by people with money but by people from many different social classes. Caruso, with his impassioned verismo (or realistic portrayal of everyday life and emotions), helped effect a transition in popular taste away from the text-centered approach of German opera to “an emphasis on the spectacle of vocal display.”[31]

2 The influence of Enrico Caruso on popular music was facilitated by the rise of the phonograph recording industry. By 1907, his recording of Vesti la giubba was the first record to sell more than a million copies. Caruso was also major influence on the great African American jazz trumpeter Louis Armstrong, who heard Caruso’s recordings when he was still a teenager working among Sicilians and Black musicians in a Sicilian-owned honky-tonk in New Orleans. “Sicilians like trumpeter Nick La Rocca, drummer Tony Sbarbaro, and clarinetist Leon Roppolo were part of the same fertile New Orleans musical environment that produced Buddy Bolden, Freddie Keppard, Joe Oliver, Sidney Bechet, Jelly Roll Morton, Louis Armstrong, Kid Ory and other of the great African American figures of early jazz.”[32]

3 According to Gennari, the most famous jazz musician to come out of New Orleans’ “Little Palermo” neighborhood was the “fiery trumpeter” and “flamboyant singer,” Louis Prima. “Like his idol Louis Armstrong, Prima embraced his role as an entertainer with infectious joy and an intuitive gift for humor.” And unlike some Italian Americans of the jazz era, who were anxious to pass as white and sometimes disparaged Black musicians, “Prima showed no interest in claiming a white identity and was proud to often be mistaken for black.” With a career spanning four decades, Prima’s influence crossed multiple genres—New Orleans jazz in the late 1920s, swing in the 1930s, jump blues from the late-40s to mid-50s, and early R&B, rock ‘n’ roll, boogie-woogie, and Italian folk music from the 1940s through the 1960s. Blending his Sicilian identity with jazz and swing and integrating Italian music and language into his songs, Prima inspired ethnic musicians generally, and Italian Americans particularly, to openly celebrate their ethnic roots.[33]

4 In the early 1930s, with the spread of modern mass media, a radio-friendly new pop music featuring an intimate, romantic vocal style emerged that became known as “crooning.” Among the first popular “radio crooners” were the Italian Americans Russ Columbo and Rudy Vallee, and the Irish American Bing Crosby. Critics who had been originally skeptical of the crooners would later come to appreciate the style, which was later perfected by Italian American singers, like Francis (Frank) Sinatra, Pierino (Perry) Como, and Dino Crocetti (Dean Martin), as embodying an “extraordinary synthesis of classical and popular styles, restoring the bel canto principles of eighteenth-century Italian opera while incorporating the casual ease introduced by the radio crooners.”[34]

Singers: Frank Sinatra, Perry Como, and Dean Martin

5 As the rock ‘n’ roll era gained momentum in the late 1950s and early 1960s, a new wave of Italian American musicians made their mark on the evolving pop music scene. Teen idol Frankie Avalon turned out number one billboard hits like Venus and Why. Walden Robert Cassotto (Bobby Darin) created unique blends of pop, rock, and swing. Connie Francis (Concetta Rosa Maria Franconero), the top-charting female vocalist of the late 1950s and early 1960s, “bridged the diverging sophisticated pop and teenage rock-and-roll audiences” with chart-toppers such as Lipstick on Your Collar.

6 In the meantime, “The Four Seasons,” an all–Italian American band initially featuring Frankie Valli, Bob Gaudio, Tommy DeVito, and Nick Massi, gained fame with a harmonious doo-wop sound and Frankie Valli’s distinctive falsetto. Among their memorable hits were songs like Sherry and Big Girls Don’t Cry.[35]

* * *

7 But according to John Gennari: “The figure who most gloriously bestrides the postwar Italian American golden age and our own is Tony Bennett (Anthony Dominick Benedetto).” Throughout a career spanning over seven decades, Tony Bennett remained grounded in his formative bel canto training and his “informal studies of jazz greats like Lester Young, Stan Getz and Art Tatum.”

8 Although a career such as Bennett’s cannot be adequately summarized in a few brief paragraphs, here are some of the stepping stones. His first successes came in the 1950s when his Crosby-styled ballads became jukebox hits. In 1953, he made a big splash with Rags to Riches, a big band number that showcased the signature vibrato that he favored in the early years. By the late 1950s, Bennett was more deeply into the jazz world, collaborating with Art Blakey, Jo Jones, Cándido Camero, and Chico Hamilton. In the early 1960s, he cut his iconic recording, I Left My Heart in San Francisco, for which he won his first Grammy Award in 1963.[36]

9 But it would be another 30 years before he won another Grammy. In the late 1960s and the 1970s, Tony Bennett’s career languished as he, along with many other jazz musicians, unwilling to compromise their musical aesthetic, struggled against the overwhelming dominance of rock and roll. Then he staged a remarkable comeback in the 1980s and ’90s. Under the shrewd management of his son Danny, Bennett began appearing in venues strategically chosen in order to get him in front of younger, “hip” audiences. Danny was sure that his father’s music would resonate with young people if they only had the opportunity to hear it. Finally, in 1994, he debuted on MTV, “becoming the preeminent custodian and proselytizer of the pre-rock Great American Songbook among fans raised on classic rock, soul, funk, disco, hip hop and alt-rock.[foonote]Gennari, 426; Wikipedia contributors, “Tony Bennett,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed December 3, 2023). [/footnote]

10 Tony Bennett continued to create music and perform well into the 21st century. At the age of 88, he began a collaboration with Lady Gaga (Stefani Joanne Angelina Germanotta), touring with her throughout 2014 and 2015, and releasing two albums with her: Cheek to Cheek in 2014 and Love for Sale in 2021. Love for Sale subsequently won a Grammy for Best Traditional Pop Vocal Album in 2022. In 2021, it was revealed that Bennett had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 2016, making the last five years of his career all the more remarkable. Tony Bennett retired in 2021, and died on June 21, 2023, at the age of 96, marking the end of an era.[37]

7.2 Cinema

1 It is impossible to do justice in a few paragraphs to the prominence of Italian Americans in the film industry. They have been film directors and actors, art directors and directors of photography, music composers, costume designers, make-up artists and so on. Unfortunately, the best we can do here is mention a few names and a few representative films. There was, of course, the great opera star Enrico Caruso, who made cameo appearances during the silent film era. But the most prominent Italian American actor prior to the emergence of the “talkies” was Rudolph Valentino, who was often regarded as Hollywood’s first male sex symbol. During the silent film era, especially in the 1920s, Valentino gained immense popularity, especially with women, for his handsome looks, charm, and passionate on-screen performances. His roles in films like The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921) and The Sheik (1921) established him as a romantic and exotic leading man.

2 Film director Frank Capra also got his start during the silent film era, although he would later become better known during the Golden Age of Hollywood for classics like It Happened One Night (1934) and Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), each of which earned him an Oscar for Best Director. A third film, You Can’t Take It with You (1938), further secured him Oscars for both Best Picture and Best Director. Capra’s legacy also includes the beloved It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), a timeless classic that has continued to resonate with audiences across the decades.

3 The first Italian American actor to win an Oscar was Frank Sinatra. He won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor in the film From Here to Eternity (1953). Sinatra went on two star in a number of other films, including The Man with the Golden Arm (1955) and The Manchurian Candidate (1962), as well as in several musicals, including Guys and Dolls (1955) and Pal Joey (1957), for which he won a Golden Globe. From the 1950s on, Italian Americans would become increasingly prominent as actors, directors, and producers in Hollywood and the broader film industry.

* * *

4 While the above details are well-known to students of Italian American cinema, Giuliana Muscio has observed that standard histories generally fail to mention how Italian immigrants in the early sound film era of the 1930s laid the groundwork for the cinematic successes of Italian Americans after the 1950s. For example, Muscio points out that no fewer than seventeen Italian-language films were produced in the United States during the 1930s—three in Hollywood and the rest “by artists of the Italian immigrant stage on the East Coast.”[38]

5 Out of these early forays into sound film, two cinematic traditions emerged, each of which approached Italian identity from a slightly different point of view: “the Italian films made in California integrated the Hollywood experience with elements of … [the era’s] Italian middle class culture, whereas the East Coast films expressed the popular culture of the Neapolitan stage, favoring the sceneggiata format” (characterized by melodramatic storytelling, dramatic dialogue, and musical elements).[39] The two traditions would eventually converge in the work of Italian American directors like Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese, who were at the forefront of the so-called renaissance of American cinema in the 1970s.[40]

* * *

6 An interesting feature of contemporary cinema is how heavily populated it is with Italian American theatrical families that were active in the formative 1930s, including “the Barbato, the Gardenia, and the Cecchini-Aguglia families, and most notably, the Pennino-Coppola family.” Francis Ford Coppola, best known for The Godfather (I, II, and III), is a good example of the tendency. Francis’ maternal grandfather Francesco Pennino, for example, was an Italian immigrant and a notable composer who managed theaters in the 1930s and collaborated on musical projects with his son-in-law Carmine Coppola—Frances Ford Coppola’s father. Carmine Coppola, in turn, contributed original music to many of his son Francis’s movies, including all three Godfather movies as well as Apocalypse Now and The Outsiders. Moreover, Francis Ford Coppola’s elder brother August and his younger sister Talia (born Coppola) Shire were also active in the movies, especially Talia, who played Connie Corleone in The Godfather series and also appeared in Rocky and many other notable movies.[41]

7 Other filmmakers in the family include Francis’s wife, Eleanor (born Neil) Coppola (right), who is a documentary filmmaker, artist, and author, as well as three of their children, including their two sons, Gian-Carlo Coppola and Roman Coppola, and their daughter Sofia Coppola. Sofia Coppola, in particular, has gained recognition for her work both in front of and behind the camera. As an actor, she made her film debut in 1972 as an infant in The Godfather, and she returned in 1990 as Mary Corleone, the daughter of Michael Corleone, in the The Godfather, Part III. As a filmmaker, she is known for her distinctive style. Films directed by Sofia Coppola have included The Virgin Suicides, Marie Antoinette, and Lost in Translation, which earned her an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay.

Coppola Family

Top: Carmine Coppola (father of August, Francis, and Talia)

Middle: August Coppola, Francis Ford Coppola, and Talia (Coppola) Shire

Bottom: August’s children—Christopher Coppola & Nicholas Cage/Francis’ children—Gian-Carlo, Roman & Sofia/Talia’s children—Jason & Robert Schwartzman

8 Even Francis’s granddaughter Gia (below), the daughter of Gian-Carlo, is in the movie business as a film director and screenwriter.[42]

9 We have barely scratched the surface of the Italian American contributions to cinema, but unfortunately, we must leave the topic behind now. As Muscio has stated: “The list of performers with Italian last names is impressive as well as extensive: De Niro, Pacino, Turturro, Travolta, Stallone, Gazzara, Aiello, Sciorra, Tucci, Mantegna, Liotta, Pesci, Sarandon, Mastrantonio, Gandolfini, the Sorvinos, Tomei, Shire, Palminteri, Sinise, Buscemi, D’Onofrio, DeVito, Cannavale, Falco and so on—too long a list to examine individual personalities’ careers.”[Muscio, 445.[/footnote]

Actors: Robert De Niro, Al Pacino, Susan Sarandon, Danny DeVito, John Turturro, Marisa Tomei, Stanley Tucci

7.3 Sports

1 Italian immigrants arriving in the United States in the late 19th and early 20th century did not bring any sport tradition with them other than bocce. In the struggle to survive in a new land, they saw no particular value in sport, considering it a waste of time. Indeed, parents usually actively discouraged their children from taking any interest, let alone participating, in sport. In time, however, Italian Americans came to participate in virtually every kind of sport at both the amateur and professional levels, and they would even become prominent managers and executives of sports teams and organizations.[43]

2 When Italian Americans finally did venture into sports, baseball tended to be their game of choice. As Lawrence Baldassaro has expressed it, “baseball had become so entrenched in popular culture that journalists imbued it with symbolic import, both as a means of teaching newcomers and their children how to become Americans and as a model of fair play and opportunity.” Baseball thus served as a major route towards the assimilation Italian Americans into American society.

7.3.1 Baseball

1 The first major league player of Italian descent was Ed Abbaticchio, who began a nine-year career in 1897 (and who also played professional football from 1895 to 1900). Francesco Pezzolo, or Ping Bodie (1911–1921), was the first Italian to attract national attention, as well as “the first of many Italian Americans from the San Francisco Bay area to play in the majors.” In 1924, Babe Pinelli emerged as both a player and the first Italian American major league umpire with a distinguished 22 year career (1935–1956). In 1925, when Tony Lazzeri of the Pacific Coast League hit sixty home runs, he “quickly became the first Italian American to achieve star status.” The Yankees, anxious to attract fans from New York’s large Italian American population, signed Lazzeri, who joined the powerful batting lineup known as “Murderers’ Row,” which included Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, among others. Lazzeri would eventually be inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1991. Lazzeri’s teammate Frank Crosetti, who joined the Yankees in 1932, played for seventeen years, then served as third base coach until 1968. Crosetti’s thirty-seven consecutive years with the Yankees remains a franchise record.[44]

2 In 1936, Joe DiMaggio, the son of Sicilian immigrants, made his debut with the New York Yankees. DiMaggio would subsequently succeed Babe Ruth as one of the baseball’s greatest players of all time and come to be acknowledged as the greatest Italian American athlete and “one of the most … admired celebrities of the twentieth century.” Over a thirteen-year career with the Yankees, DiMaggio established a legacy marked by three American League Most Valuable Player awards and many other notable achievements, including a still unsurpassed fifty-six-game hitting streak in 1941. Beyond baseball, he became a cultural phenomenon as well, inspiring songs and literature. Nicknamed “Joltin’ Joe,” DiMaggio’s achievements were a great source pride for Italian Americans. Less well known is the fact that Joe’s older brother Vince and his younger brother Dom were also major league players; Dom, over ten seasons with the Boston Red Sox, was a seven-time All-Star selection, and Vince, over a ten-year career, was a two-time All-Star.[45]

3 Despite the immense popularity of players like DiMaggio, media responses to Italian American ball players were ambivalent. Celebratory stories often carried a patronizing tone, using derogatory terms like “dagos” and “wops,” reflecting a marginalization that persisted until the 1950s. Nevertheless, from the era of DiMaggio till the end of the century, players of Italian descent continued to distinguish themselves on the diamond: Rocky Colavito, Tony Conigliaro, Frank Malzone, Rico Petrocelli, Joe Pepitone, Larry Bowa, Steve Sax, Jack Clark, Jim Fregosi, Joe Torre, Ron Santo, and Sal Bando, among others. Italian Americans players also distinguished themselves as pitchers, with Dave Giusti, Dave Righetti, Andy Pettitte, and John Franco as notable examples. And while in the early decades of the 21st century, players of Italian descent may have decreased in numbers, they continued to grace the game with players like Barry Zito, Dustin Pedroia, and Joey Votto making significant contributions.[46]

4 Italian Americans also made inroads into baseball management. “After Yogi Berra became the first Italian American manager to win a pennant (1964), Billy Martin became the first to win a World Series title in 1977, followed by Tommy Lasorda (1981 and 1988) and Joe Altobelli (1983). By the late 20th century, there were six highly successful baseball managers of Italian American heritage: Joe Torre, Tony La Russa, Joe Maddon, Larry Bowa, Mike Scioscia, and Joe Girardi.[47]

7.3.2 Boxing

1 Although “Italian Americans have made their greatest mark in baseball,” it was through boxing that they first entered into the world of sport in the United States. “Italian American fighters rose to prominence in the 1920s” winning fourteen world titles. Every year from 1917 to 1929, there was at least one Italian American titleholder. Many boxers of Italian background fought under assumed names to avoid discrimination or attract fans from other ethnic groups. Pete Herman (Peter

Gulotta), the bantamweight champion from 1917 to 1920 and again in 1921, was among the first universally recognized titleholders, and Johnny Dundee (Giuseppe Curreri) held titles in junior lightweight and featherweight between 1921 and 1924. Other notable champions included Rocky Kansas, Salvatore Mandala (fighting as Sammy Mandell), and Tony Canzoneri, who achieved the remarkable feat of winning world championships in three weight classes.[48]

2 Italian American fighters continued to be prominent through the middle of the twentieth century. Between the mid-1940s and mid-1960s, Italian Americans were particularly prominent in the middleweight class. Rocky Graziano (Rocco Barbella), Jake LaMotta, Carmen Basilio, and Joey Giardello (Carmine Tilelli) all won the middleweight crown. The lives and careers of Graziano and LaMotta were both adapted into hit movies. LaMotta in particular was immortalized in cinema by none other than the renowned Italian American director Martin Scorsese in his much-acclaimed 1980 film, Raging Bull, in which Robert De Niro played LaMotta and won an Oscar as Best Actor.[49]

3 Despite all the successes recorded by Italian American boxers, the most prestigious achievement in the sport, the world heavyweight title eluded them until September 23, 1952, when Rocky Marciano (Rocco Marchegiano) knocked out Jersey Joe Walcott to become the first Italian American heavyweight champion. Although somewhat small for a heavy weight at 5 feet 10 inches and 180–190 pounds, Marciano had tremendous punching power in both hands. After the title fight with Walcott, Marciano defended his title six times before retiring in 1956. He “is the only undefeated heavyweight champion in history, winning all forty-nine of his bouts, forty-three by knockout.” Today, Marciano remains the most revered Italian American boxer in the history of the sport.[50]

4 There have been other Italian American champions from the 1950s on, including Tony DeMarco, Willie Pastrano, Vito Antuofermo, Arturo Gatti, Ray Mancini, and Vinny Pazienza. However, according to Baldassaro, the 1950s were the glory days for Italian American fighters. Indeed, an Italian American was featured in Ring magazine’s “Fight of the Year” in all but two years between 1945 and 1959.[51]

5 A discussion of Italian American contributions to the world of boxing would not be complete without acknowledging the significant roles played by several notable trainers—Cus D’Amato, Angelo Dundee (Angelo Merena), and Lou Duva—all of whom have earned spots in the International Boxing Hall of Fame. Of the three, perhaps the most well-known is Angelo Dundee, renowned for his astute guidance in shaping the career of the legendary Muhammad Ali.[52]

7.3.3 Football

Activity 7.1

Based on your understanding of subsections 1–3 of the chapter, engage with the following tasks and discuss your responses with one or more fellow readers.

Create two tables like the ones below and record key bits of information in Column 2 that is responsive to the topic headings listed in Column 1.

1. First Italians in the Americas

| Early Italian presence in the Americas

|

|

| Explorers

|

|

| Soldiers and priests

|

|

| Artisans, craftsmen, and musicians

|

2. Late 19th and early 20th century immigration waves

| Characteristics of Italian immigrants (1880–1920)

|

|

| Factors driving immigration

|

|

| Challenges

|

|

| Typical forms of employment

|

|

| Community formation

|

Answer and discuss the following questions with one or more fellow readers.

- What evidence does the text offer to support the proposition that American labor leaders largely misjudged the willingness of Italian workers to fight for workers’ rights?

- What are obstacles did Italian Americans face in their efforts to get elected political offices? Identify a notable exception and describe that individual’s most notable achievements.

Activity 7.2

Based on your understanding of subsections 4–6 of the chapter, answer and discuss the following questions with one or more fellow readers.

- Why were Italian Americans attracted to Benito Mussolini? In what way was this fascination less remarkable than it might seem today?

- Identify several ways in which World War II “changed everything” for Italian Americans.

- How did the political fortunes of Italian Americans change after the 1948 U.S. elections?

Activity 7.3

Based on your understanding of subsections 7–9 of the chapter, engage with the following tasks and discuss your responses with one or more fellow readers.

1. Music and Cinema

Create a table like the one below and record key bits of information in Column 2 that is responsive to the topic headings listed in Column 1.

| Music | Cinema | |

| General observations on Italian American contributions to music and cinema

|

||

| Notable artists & achievements (1900–1929)

|

||

| Notable artists & achievements (1930–1959)

|

||

| Notable artists & achievements (1960–present)

|

2. Sports

Answer and discuss the following questions with one or more fellow readers

a. In what way did the initial orientation of Italian Americans towards sport differ from that of Irish Americans?

b. In what ways did the earliest sports achievements of Italian Americans resemble those of Irish Americans? How might these similarities be explained?

c. What differences can you discern in Italian Americans’ participation in sports (at least as reflected in this text) from about the 1970s on?

Media Attributions

- Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello © Martin Falbisoner is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Italian Immigrants, 1905 © Lewis W. Hine is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Little Italy, Boston © Ajay Suresh is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Millworkers Banner of Revolt © Author Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Gallery Images – 1912 Lawrence, MA Millworker’s Strike

- Lawrence, MA, Children’s Exodus © Ex-Bain News Service is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Standoff Between Militia and Strikers © Author Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Fiorello LaGuardia © Fred Palumbo is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license. Used with permission under Fair Use

- Benito Mussolini © Author Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Frank Capra Receiving Medal of Honor © U.S. Army is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Gallery Images – Prominent Italian American Government Officials

- NY Governor Mario Cuomo speaks at Cornell Convocation May 1987. Film scan. © Kenneth C. Zirkel is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Geraldine Ferraro, 1998 © Rebecca Roth is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Antonin Scalia © Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Nancy Pelosi © John Harrington is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Enrico Caruso © Author Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Louis Prima © William P. Gottlieb is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Gallery Images – Italian American Singers

- Frank Sinatra © Capitol Records is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Perry Como, 1962 © NBC Television is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Dean Martin, 1958 © Elmer Holloway is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Connie Francis, 1961 © ABC Television is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Rudolph Valentino, 1921 © Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Martin Scorsese © Montclair Film is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Pacino and Brando in The Godfather © Paramount Pictures is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license. Used with permission under Fair Use

- Eleanor Coppola © Dick Thomas Johnson is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Carmine Coppola © Author Unknown is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license. Used with permission under Fair Use

- Gallery Images – Coppola Film Family

- August Coppola © Author Unknown is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license. Used with permission under Fair Use

- Francis Ford Coppola © Greg2600 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Talia Coppola Shire © ABC Television is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Christopher Coppola © hinnk is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Nicolas Cage © Georges Biard is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Gian-Carlo Coppola © Author Unknown is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license. Used with permission under Fair Use

- Roman Coppola © Martin Kraft is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Sofia Coppola © Georges Biard is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Jason Schwartzman © Sachyn is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Robert Schwartzman © Sina Nill is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Gia Coppola © thepaparazzigamer is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Gallery Images – Famous Italian American Actors

- Robert De Niro © Petr Novák, Wikipedia is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Al Pacino © Thomas Schulz is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Susan Sarandon © GuillemMedina is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Danny DeVito © Gage Skidmore is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- John Turturro © David Shankbone is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Marisa Tomei © Elena Ternovaja is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Stanley Tucci © Martin Kraft is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Tony Lazerri © Lou or Nat Turofsky is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Dimaggio and Marciano with Eisenhower © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Jennifer Rizzotti © Sphilbrick is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Diana Taurasi © SusanLesch is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Mary Lou Reton © Tony Barnard is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Americans with Italian Ancestry © Abbasi786786 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Roger Daniels, Coming to America: A History of Immigration and Ethnicity in American Life, 2nd edition, (New York: Harper Perennial, 2002), 188–189. ↵

- Daniels, Coming to America, 189–190. ↵

- Daniels, 190. ↵

- Daniels, 190–192. ↵

- Daniels, 191–193. ↵

- Wikipedia contributors, "Italian Americans," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed October 21, 2023). ↵

- Marcella Bencivenni, "From Margins to Vanguard to Mainstream: Italian Americans and the Labor Movement." In The Routledge History of Italian Americans, 1st ed., eds. William Connell and Stanislao Pugliese, (New York: Routledge, 2016), 271. ↵

- Bencivenni, "From Margins to Vanguard," 271–272. ↵

- Bencivenni, 272. ↵

- Daniels, 193–194. ↵

- Bencivenni, 272. ↵

- Bencivenni, 272. ↵

- Bencivenni, 273. ↵

- Bencivenni, 273. ↵

- Bencivenni, 273–274. ↵

- Bencivenni, 277–278. ↵

- Bencivenni, 278. ↵

- Bencivenni, 281. ↵

- Stefano Luconi, "The Bumpy Road Toward Political Incorporation, 1920–1984." In The Routledge History of Italian Americans, 1st ed., eds. William Connell and Stanislao Pugliese, (New York: Routledge, 2016), 319. ↵

- Luconi, "The Bumpy Road," 319. ↵

- Luconi, 320–322. ↵

- Luconi, 322. ↵

- Dominic Candeloro, "World War II Changed Everything." In The Routledge History of Italian Americans, 1st ed., eds. William Connell and Stanislao Pugliese, (New York: Routledge, 2016), 382. ↵

- Stanislao G. Pugliese, "Fascism and Anti-fascism in Italian America." In The Routledge History of Italian Americans, 1st ed., eds. William Connell and Stanislao Pugliese, (New York: Routledge, 2016), 349. ↵

- Pugliese, "Fascism and Anti-fascism in Italian America," 354. ↵

- Candeloro, "World War II Changed Everything," 374. ↵

- Candeloro, 378; 382. ↵

- Candeloro, 382. ↵

- Luconi, 325–326. ↵

- Wikipedia contributors, "Italian Americans," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed November 30, 2023). ↵

- John Gennari, “Groovin': A Riff on Italian Americans in Popular Music and Jazz.” In The Routledge History of Italian Americans, 1st ed., eds. William Connell and Stanislao Pugliese, (New York: Routledge, 2016), 415–416. ↵

- John Gennari, “Groovin'," 417. ↵

- Gennari, 418–419. ↵

- Gennari, 421–422. ↵

- Gennari, 426–428. ↵

- Gennari, 426. ↵

- "Tony Bennett," Wikipedia. ↵

- Giuliana Muscio, "Italian Americans and Cinema." In The Routledge History of Italian Americans, 1st ed., eds. William Connell and Stanislao Pugliese, (New York: Routledge, 2016), 433–434. ↵

- Muscio, "Italian Americans and Cinema," 435. ↵

- Muscio, 443. ↵

- Muscio, 444. ↵

- Muscio, 444; Wikipedia contributors, "Sofia Coppola," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed December 6, 2023); Wikipedia contributors, "Gia Coppola," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed December 6, 2023). ↵

- Lawrence Baldassaro, "Italian Americans in Sport." In The Routledge History of Italian Americans, 1st ed., eds. William Connell and Stanislao Pugliese, (New York: Routledge, 2016), 464. ↵

- Baldassaro, "Italian Americans in Sport," 464–465. ↵

- Baldassaro, 465. ↵

- Baldassaro, 466–468. ↵

- Baldassaro, 468. ↵

- Baldassaro, 468–469. ↵

- Baldassaro, 469. ↵

- Baldassaro, 469. ↵

- Baldassaro, 470. ↵

- Baldassaro, 470; Wikipedia contributors, "Angelo Dundee," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed December 7, 2023). ↵

- Baldassaro, 470. ↵

- Baldassaro, 471–472. ↵

- Baldassaro, 472; Wikipedia contributors, "Jennifer Rizzotti," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed December 8, 2023). ↵

- Wikipedia contributors, "Diana Taurasi," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed December 8, 2023). ↵

- Baldassaro, 473. ↵

- Baldassaro, 473–476. ↵

- Baldassaro, 474–475. ↵