2 Hispanic America

1. U.S. History with a Spanish Accent

1 In his wonderfully thought-provoking book, Our America, Felipe Fernández-Armesto upends the standard Anglo-American account of U.S. history, which imagines the country as originating with the founding of the English colonies of Jamestown (1607) and Plymouth (1620), and which treats the subsequent history of the country as if it unfolded from east to west. Fernández-Armesto rotates the picture to tell the story of the country as it unfolded from south to north. In this telling, the United States’ colonial origins are as much Spanish as they are English, and the descendants of the first Hispanic Americans have as much reason to count their ancestors among the nation’s founders as does any Anglo descendant of a Virginia planter or a New England Pilgrim.

2 Fernández-Armesto’s “Hispanic-accented account,” helps us see “today’s plural America” as the product of “the whole of America’s past, not a threat to traditional U.S. identity.” His alternative narrative intersects with the Anglo narrative while highlighting an argument that there is “no single frontier, no single language, or tradition, or identity, no manifest destiny, no culture that deserves to be hegemonic or that predominates or ought to predominate by virtue of U.S. historic experience.”[1]

2. Early Spanish Settlements in (Future) U.S. Territory

1 Founded over a hundred years before Jamestown, Puerto Rico was the first Spanish colony in what today is a U.S. territory. In 1508, Spanish explorer and conquistador, Juan Ponce de León founded a settlement at Caparra in Puerto Rico. Caparra was abandoned in 1521, but the city of San Juan, barely 8 miles away, replaced it as the capital of Puerto Rico, making San Juan the oldest continuously inhabited European city in the United States.[2]

2 Nobody thinks of Puerto Rico as the place where U.S. history began. That might be, in part, because the island of Puerto Rico became a U.S. possession only after the end of the Spanish-American War in 1898. It then became a U.S. territory after the passage of the Jones-Shafroth Act in 1917, which also granted Puerto Ricans U.S. citizenship.[3] Yet today, their fellow citizens in the 50 states too often forget the fact that anyone born in Puerto Rico is a U.S. citizen.

3 Putting Puerto Rico aside, the oldest continuously inhabited European settlement in the continental United States is San Agustín (Saint Augustine), Florida. Founded by the Spanish in 1565, it remained a Spanish city until 1819, when Spain ceded Florida to the United States.[4]

4 Another settlement in the United States with a Spanish heritage almost as old, if not older than Jamestown, is Santa Fe, New Mexico. The area was already under Spanish control in 1598,[5] even if the city of Santa Fe proper was not established until 1610, three years after Jamestown. This makes Santa Fe the oldest continuously inhabited state or territorial capital in the continental United States.[6]

3. Hispanic America Today

3.1 The Term Hispanic

1 Before continuing, it might be a good idea to briefly discuss the term Hispanic, which appears in this chapter’s title, and which I have already used several times in the above sections, as if it were clear and unambiguous, which it is not. Indeed, just as the term Indian may be a somewhat problematic way to refer to America’s Indigenous people, who, as discussed in Chapter 1, do not really represent a monolithic group, the term Hispanic obscures much about the diversity of American people to whom that label could be said to apply.

2 In fact, prior to the 1970s, the overwhelming majority of Americans that would come to be regarded as Hispanic were of either Mexican, Puerto Rican, or Cuban descent, and that is how they tended to identify. The idea that they all belonged to one, unified panethnic group with overlapping concerns never occurred to them. The drive to construct a panethnic Hispanic identity only began to take shape in the 1970s as civil rights activists, government agencies, and Spanish-language media executives, each with their own particular interests in mind, promoted the idea of an American Hispanic community animated by shared interests.[7]

3 Without getting into too much detail on the historical and sociological reasons for the emergence of the term Hispanic, suffice it to say that after its introduction in the decennial census in 1980, the term spread rapidly throughout academia during the 1980s.[8] Meanwhile, a competing term, Latino/Latina, became increasingly popular in grassroots movements and among community activists. While the term Hispanic, which emphasized Spanish heritage and language, tended to strike activists as too conservative, the term Latino/Latina seemed better aligned with their New World identities and better suited to their progressive critiques of colonialism and the struggle to undo it.

4 In current academic discourse, the terms Hispanic and Latino or Latina (or more recently Latinx) tend to be used interchangeably. But as with all labels connected to cherished identities, individuals tend to embrace different labels for their own particular reasons. The term Hispanic, in particular, is fraught with limitations. It centers Spanish heritage and language, effectively excluding millions of Latin Americans—most notably Brazilians—whose primary language is Portuguese rather than Spanish. This raises a crucial question: if the term Hispanic is meant to encompass those with origins in Latin America and Spain, why does it exclude Portuguese-speaking Brazil, which shares many of the same colonial and postcolonial dynamics as its Spanish-speaking neighbors?

5 The emphasis on Spanish also flattens the significant racial and cultural diversity of Latin American populations, many of whom do not claim Spanish ancestry as a defining feature of their identity. Indigenous, Afro-descendant, and Asian Latin Americans, for example, may feel alienated by a label that foregrounds European heritage. Ultimately, Hispanic functions as an externally imposed bureaucratic category, shaped more by governmental and institutional convenience than by how people actually understand their own identities.

6 Nevertheless, despite its limitations, Hispanic remains a useful term in this chapter for referring broadly to Spanish-speaking populations in the United States. While imperfect, it provides a practical framework for discussing shared historical and social experiences, even as the diversity it encompasses should not be overlooked.

3.2 Demographics of Hispanic America Today

1 According to the 2020 U.S. Census, Hispanics (alternatively designated in the census as Latinos) constitute the largest minority group in the United States. Just over sixty-two million people (or 19% of the U.S. population) self-identified as Hispanic or Latino in the census. Among all Hispanics, people of Mexican origin numbered over thirty-seven million, accounting for nearly 62% of the U.S. Hispanic population. People of Puerto Rican heritage constituted the second largest group at about 5.8 million. And the next six largest Hispanic origin groups were Cubans, Salvadorans, Dominicans, Guatemalans, Colombians and Hondurans.[9]

2 Because the issue of immigration is continually in the news—with the U.S.–Mexico border often in the spotlight—some non-Hispanics may be under the impression that most Latinos are immigrants and perhaps even undocumented. However, it is important to keep in mind that the vast majority of all Latinos, roughly 80%, are U.S. citizens, either by birth (67%), or naturalization (13%). The other 20% are non-citizens, some of whom are legal residents and others of whom are undocumented.[10]

3 Of course, the number of Latinos living in the U.S. who were not born in the U.S. but who immigrated from elsewhere is also not insignificant. In 2020, foreign-born Latinos, i.e., naturalized citizens and non-citizens taken together accounted for about one-third of the U.S. Hispanic population, or roughly twenty million people. But again, just to emphasize the point, the vast majority of Latinos living in the United States are U.S. citizens.[11]

3.3 The Mexican Diaspora

1 While the title of this chapter is “Hispanic America,” practical considerations preclude me from exhaustively covering all of Hispanic America. Instead, the rest of the chapter is devoted to the story of the largest segment of the U.S. Hispanic population, people of Mexican descent, who, as noted above comprised a whopping 62% of the entire Hispanic population or more than six and a half times the number of the next largest group, the Puerto Ricans, who comprised just 9.7% of the U.S. population.[12]

4. The Spanish Conquest of Mexico

1 The history of the United States is inextricably linked to that of its southern neighbor, Mexico. Like the United States, Mexico began as a European colony. What today we call Mexico was forcibly taken from indigenous people, while the people themselves were subjugated, marginalized, or absorbed through intermarriage with the conquerors. Later, Mexico, like the United States, separated from the mother country by means of armed rebellion. In this chapter, we will explore briefly how lands once controlled by indigenous peoples became colonies of Spain, then sovereign Mexican states, and finally, in some places, U.S. territories and eventually U.S. states. We’ll begin our exploration with a brief overview of the history of Mexico, or New Spain as it was called before Mexican independence.

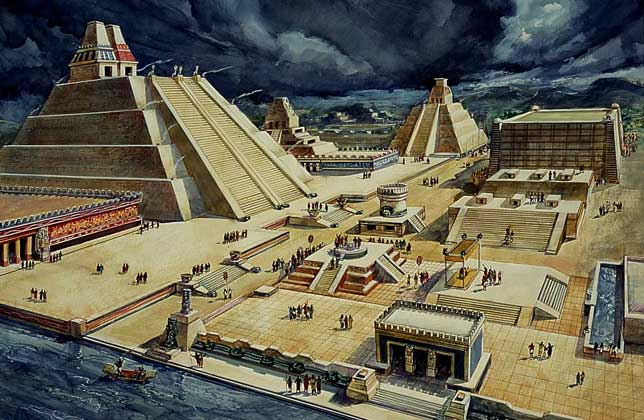

2 It will be convenient to begin our story in Cuba. In 1519, two years before the founding of San Juan, (Puerto Rico), the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés sailed from Cuba to the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico. His intention was to conquer the Aztec empire centered in Tenochtitlan (the site of modern-day Mexico City). With a population of perhaps 200,000 Tenochtitlan was undoubtedly the largest city in the New World. It may have been five times the size of London at the time and was rivaled only by European cities like Paris and Venice.[13] At any rate, it was by Cortés’ own account[14] a fabulous city.

3 By the time Cortés first set out for the Yucatan, two expeditions had preceded him, and these provided him with some knowledge of the land and the people. Moreover, he learned even more as he encountered various indigenous groups on his way to Tenochtitlan. He learned that the Aztecs (or Mexica, as they called themselves) had many enemies among non-Aztec peoples whom the Aztecs dominated by fear and intimidation and from whom they extracted tribute in the form of foods, clothing, and numerous other valuable commodities. Cortés was able to exploit the animosities some of these groups held towards the Aztecs, convincing them to join him as he made his way towards Tenochtitlan. However, when he encountered resistance, Cortés pillaged and burned native towns, and massacred the people.[15]

4 When Cortés reached Tenochtitlan, the Aztec emperor Montezuma welcomed the Spanish as royal guests.[16] It is not entirely clear why Montezuma allowed the Spanish into the city so readily, but one theory is that he mistook Cortés for a god whose arrival had long been prophesied. Historian Camilla Townsend disputes this theory, however, on the grounds that the story only began circulating decades after the Conquest, and Cortés himself, who wrote in detail about the events at the time, never mentioned such an idea. Instead, Townsend contends, Montezuma recognized the formidable advantage of the Spanish, with their metal weapons, crossbows, and cannons, backed by an army of thousands of indigenous Aztec enemies, and was unwilling to start a war he was sure to lose. Instead, he sought to buy the invaders off and perhaps stall for time.[17]

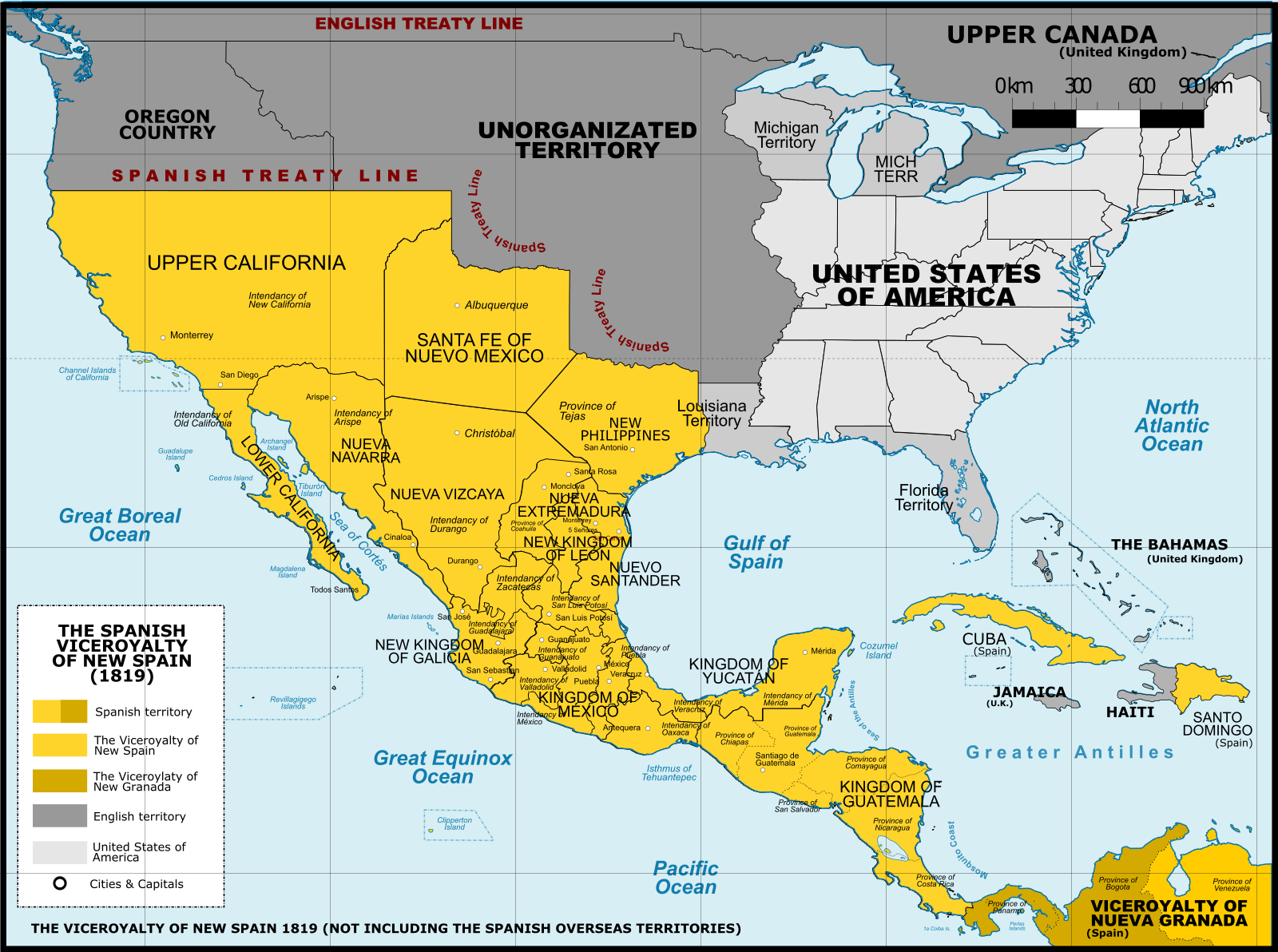

5 In the end, Montezuma failed. He was killed; war broke out, as did a deadly smallpox epidemic, which further weakened the Aztecs, and ultimately, Tenochtitlan fell to the Spanish invaders in 1521. Tenochtitlan, now in ruins, would eventually become Mexico City,[18] the capital and base for further exploration and conquest of a vast territory that became known as the Kingdom of New Spain under the direct control of the Spanish Crown.

5. The Kingdom of New Spain

1 Many of the most important cities in Mexico were founded in the next twenty-five years after the fall of the Aztec Empire. These cities became outposts of Spanish settlement, which was concentrated in Mexico City while the countryside remained inhabited mainly by indigenous populations.[19]

2 In the earliest years of the kingdom, conquistadors like Cortés sought to maintain and enrich themselves by exploiting these indigenous communities through the encomienda system. The encomienda was a Spanish legal institution by which the king rewarded those who had risked their lives in frontier warfare by granting them the right to collect tribute from the native population. In return, the recipient of the encomienda (the encomendero) was supposed to assume responsibility for protecting and Christianizing the Indians.[20]

3 Later, the Crown abolished the encomienda system for fear that it was creating a politically influential, wealthy class that abused the Indians whom the king considered his subjects. However, the encomienda system was replaced with the repartimiento, a system that required native men to perform periodic work considered essential for the public good. Participation in the repartimiento was compulsory, although the law stipulated that Indians had to be paid for their labor. It also set limits on the length of their service and on the type of work that could be required.[21] In practice, however, the system was often abused in ways that amounted to little more than slavery by a different name.[22]

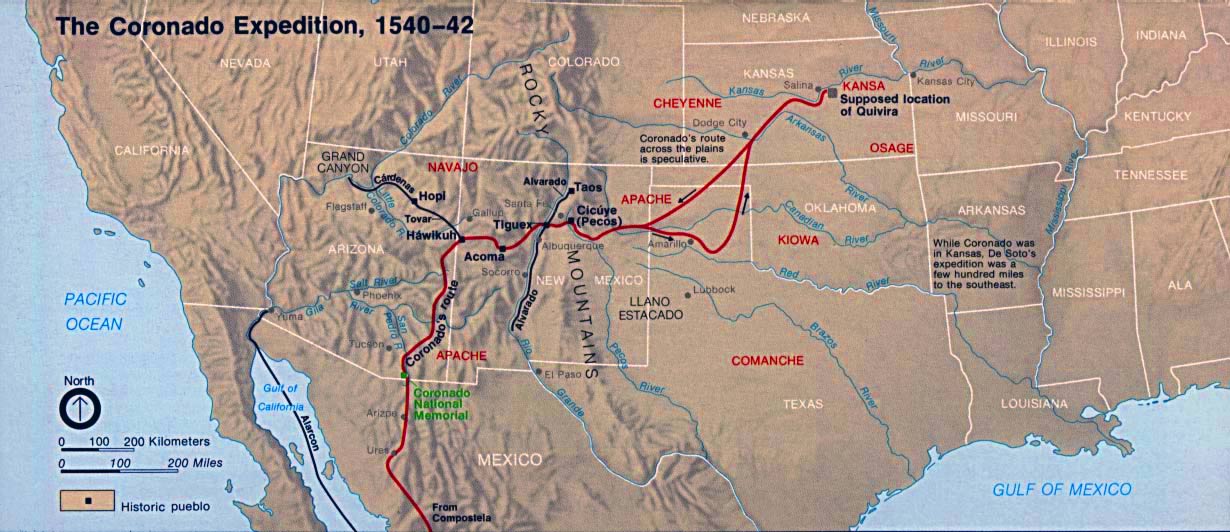

4 In the meantime, restless conquistadors, attracted by fantastic stories of fabulously rich cities in the north, went looking for them. One such explorer was Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, who led an expedition in 1540 in search of the Cities of Cîbola, often referred to today as the mythical Seven Cities of Gold.[23] Instead, Coronado found the sunbaked, mud-brick apartments of a modest town of Zuni people.[24] The search for Quivira, another supposed city of gold, only led into the vast plains of Kansas.[25]

5 While Coronado never found what he was looking for, his expedition ranged over eastern Arizona, northern New Mexico, and the panhandles of Texas and Oklahoma and into northeastern Kansas. In the 1500s, these lands were all claimed by New Spain. Three centuries later, they would become a contested frontier, over which Mexico, after gaining its independence from Spain, would go to war with the United States.

6 As for settling the far north, the first serious attempt was in 1598 when Juan de Oñate was commissioned by the Spanish Crown to explore and colonize it. Oñate led about six– or seven–hundred settlers into New Mexico and established a number of settlements, including the precursors of present-day Santa Fe, New Mexico, and El Paso, Texas. Of course, as in most cases of European encroachment on indigenous lands, the newcomers were not welcome. Oñate himself is infamous for his brutal dealings with the native people, which set the stage for a situation that would endure for three centuries. Natives and settlers alike greatly feared and mistrusted each other, and the settlers would maintain themselves by violent means, even as natives found ways to adapt to their presence. Moreover, the isolation of the far north by hundreds of miles from the closest settlements in northern New Spain would keep the settlements from growing very quickly so that throughout the 1600s, the Spanish population in New Mexico was probably never larger than three thousand. Nevertheless, this population was large enough to transform the character of the nearby land and indigenous people, at the same time that the land and indigenous people transformed the settlers.[26]

6. Pobladores of the Far North

1 In the beginning, New Spain was a kingdom largely of Spaniards, on the one hand, and Indians (or in Spanish, Indios), on the other. However, mestizaje (racial mixing) soon turned it into a kingdom of mestizos (persons of mixed Spanish and Indian heritage). A person could be mestizo by virtue of biological union or simply by borrowing and blending the cultural practices of the two groups. But being mestizo carried some stigma; Spaniards and Indians alike disapproved of mestizo persons. Nevertheless, labor was scarce, and mestizos had an important role to play in the frontier economy, so their presence became a fact of life. At the same time, labor shortages were also offset by the importation of African slaves, and their arrival further contributed to the growing mestizaje.[27] Over the second half of the 18th century, the population grew ever more racially mixed, settling on ranches, haciendas, and mining towns across the borderlands.[28]

2 The majority of pobladores (settlers) and soldiers who went north were mestizos,[29] and by the 1700s, the mestizo population was already a majority in the provinces of Nueva Vizcaya, Nuevo León, and Nuevo México.[30] The far northern reaches of the frontier from California to Texas became sites of extraordinary cross-cultural and racial amalgamation. The exact nature and extent of mixing varied from region to region, depending on ecological conditions and the characteristics of the native populations of each region. In Arizona and Texas, where the pobladores encountered more nomadic and war-like tribes, there was less intermixing, while in California and New Mexico, where the tribes were more settled, there was more intermixing. As a result, farming and ranching flourished earlier in California and New Mexico in ways they did not in Arizona and Texas.[31]

3 On the furthest reaches of the northern Spanish frontier lay California, where the Catholic Church provided the means of settlement through an extensive system of missions the purpose of which was to convert the indigenous peoples to Christianity. Of course, California was not the only site of Catholic missions, but it is where the mission system was most extensive. California missions were spaced about thirty miles apart, one day’s journey by horse, and reinforced by the strategic placement of presidios (military fortresses) for keeping order. However, despite the seemingly more orderly settlement of California, fewer pobladores migrated there from New Spain, so the Spanish population remained smaller than in other places on the northern frontier. Unfortunately, the California missions also became infamous for their paternalism, abuse, and harsh punishment of mission Indians in response to the Indians’ supposed transgressions.[32]

7. Mexican Independence

1 Settlement of the northern frontiers had proceeded slowly throughout the 1700s. As the early 1800s got underway, many Mexicans found themselves disenchanted with Spanish rule, and in 1810, a Catholic priest named Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla launched an unsuccessful crusade for Mexican independence. Although Hidalgo was captured and executed, insurgents kept the independence movement alive until 1821, when an army officer named Agustín de Iturbide finally succeeded in conducting a bloodless coup, making Mexico an independent country. Now just as all of this was happening in Mexico, the United States was on the verge of a major era of empire building.

8. U.S. Annexation of Mexican Land

1 By the early 19th century, New Spain had been exploring the North American continent for three centuries already, while the United States was only just beginning to probe its western frontier. In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson purchased the so-called Louisiana territory formerly claimed by France, virtually doubling U.S. land area overnight. The following year, Jefferson commissioned Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to explore and map the newly purchased territory. The Lewis and Clark expedition left Missouri in 1804, reached the Pacific Ocean on the coast of Oregon in 1805, and returned in 1806 with their reports of the vast territories of the Great Plains and the Northwest.

2 The opening of the Louisiana Territory to Anglo settlement put Anglo Americans in closer proximity to Spanish Territory. Then in the 1820s, Anglos began pouring across the Mexican border and settling in the territory then known as Tejas (Texas). Many of the newcomers were southern U.S. slaveholders eager to find new lands for their lucrative cotton growing enterprise. Alarmed, the Mexican government sent a commission to investigate.[33] A Mexican army officer of the day described the situation this way:

The Americans from the north have taken possession of practically all the eastern part of Texas, in most cases without the permission of the authorities. They immigrate constantly, finding no one to prevent them, and take possession of the sitio [location] that best suits them without either asking leave or going through any formality other than that of building their homes.

3 In 1830, the Mexican government outlawed slavery and prohibited continued American immigration. The Americans considered it an outrage and continued to cross the border in defiance of Mexican law. By 1835, there were about twenty thousand Anglos in Texas compared to only four thousand Mexicans. Men like Stephen Austin began agitating for an American takeover of Texas,[34] characterizing the conflict in racist and Hispano-phobic terms as “a war of barbarism and of despotic principles, waged by the mongrel Spanish-Indian and Negro race, against civilization and the Anglo-American race.”[35]

4 In 1836, there was a revolt in Texas, known as the Texas Revolution, when 175 Texas rebels launched an armed insurrection in San Antonio. The rebels included both Anglo-Texans and Tejanos, Mexican citizens, who had begun to identify with Texas as their homeland quite apart from Mexico. In other words, the Tejanos and the Anglo-Texans shared a similar desire to be free from the dictates of a centralist Mexican government in faraway Mexico City. When the Texans declared Texas to be an independent republic, the Mexican president and general Antonio López de Santa Anna brought an army to Texas to put down the revolt. On February 23, Santa Anna confronted the rebels in San Antonio where the rebels barricaded themselves inside the Alamo, a Catholic mission turned military fort. The rebels refused to surrender and fought to the death against the Mexican army after a 13-day siege. Santa Anna went on to capture the town of Goliad where he slaughtered 400 American prisoners. The American, Sam Houston, mounted a counterattack, surprising Santa Anna’s army at San Jacinto and slaughtering 630 Mexican soldiers.[36] These events basically established Texas as an independent republic although Mexico refused to acknowledge it as such.

5 At this point, it may be important to remind readers of a common American misconception. Americans, if they know anything at all about the Alamo, sometimes operate under the false narrative that Santa Anna attacked the United States and that the defenders of the Alamo were patriots defending their country against a foreign invader. The Alamo was in fact in Mexican territory, and Santa Anna’s intent was to put down a rebellion taking place in Mexico. It is also important to note that among the Anglo defenders of the Alamo were Tejanos, Mexican citizens who had begun to identify with Texas as their homeland quite apart from either Mexico or the United States. In other words, the Tejanos and the Anglo-Texans shared some sympathies with respect to their view of the Texas territory.

6 Texas remained a de facto independent republic until 1845 when the U.S. government, which also had an eye on gaining control of California, formally annexed Texas, thus starting a war with Mexico that would last for two years. The U.S. ultimately defeated Mexico, and when the war ended in 1848, with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the United States had taken practically the entirety of the American Southwest, including present-day California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas (and of course everything else further north that may have once been Mexican territory).

9. Foreigners in Their Native Land

1 Suddenly thousands of Mexicans found themselves inside the United States. They had not crossed over any border, rather the border had crossed over them. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo gave Mexicans living in the conquered territory the choice of either leaving within one year or becoming American citizens. Most Mexicans, seeing very little difference between one government and another, chose to stay in their established homes. They saw no reason why the frontier, which had always been insulated from the levers of government, would not continue to be relatively free. Now, a people whose ancestors had first been Spanish subjects and later Mexican citizens became United States citizens.[37]

2 Whether they recognized it or not, “Mexican Americans” had suddenly become a new constituency within U.S. society, but it is important to acknowledge that most did so with a certain sense of alienation. Where Spanish had once been the primary language, English was becoming more and more prevalent.[38] And Mexican communities that had interacted with Indians since the 16th century were now forced to deal with a different people who were powerful enough to assert their own political will. Anglo capitalists, entrepreneurs, lawyers, and other professionals moved in and took control of the political system, dislocating Mexican land owners, displacing local merchants, gaining control over agricultural production, appropriating raw materials, and in many cases, pushing Mexicans to the margins of society.[39]

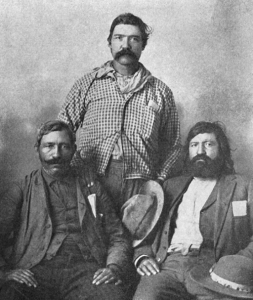

3 Many upper-class Mexican elites, hoping to earn a niche in the rapidly developing capitalist order, strove to maintain social distance from lower-class Mexicans whom they considered to be their “inferiors.” They hoped to gain acceptance among Anglos by labeling themselves “Spaniards.” Some few succeeded.[40] Meanwhile, the lower classes remained as always in their customary roles as laborers. Many continued making their livings as workers on ranches and farms.[41]

4 On the other hand, Mexican landowners found themselves continually fighting off attempts by Whites to separate them from their lands. The sheer variety of land theft schemes are too numerous to list, but certainly fraudulent legal maneuvering was one effective means of gaining control of a landowner’s property. In other instances, Anglo men sometimes acquired land by marrying Mexican women, then altering the purpose of a ranch to the financial detriment of everyone whose livelihood depended on the ranch. Outright intimidation and violence were also not uncommon.[42] When landowners lost their lands, the unemployed workers had to turn to day labor, seasonal work, and generally, low-paid and unstable forms of employment.[43]

5 Despite these sorts of disruptions, becoming a U.S. territory did not, in the short-term, radically alter Mexican-Americans’ everyday lives. That is, people still maintained the same basic cultural patterns, e.g., living arrangements, cooking, language use, religious practices, norms of conduct, and work habits, (even if the work was now under the supervision of the new Yankee bosses).[44] Nor was new immigration from Mexico a major factor in community development.[45] Instead, the main factor that affected community development was geographic clustering. That is, Anglos and Mexicans tended to settle different areas of the region. For example, Southern California tended to remain predominantly Hispanic, while in northern California, Anglos predominated. Mexican Tejanos (Texans) preferred to farm and ranch the chaparral country from San Antonio south to the Rio Grande and along the border to El Paso, while Anglo cattle ranchers outnumbered Mexicans in the east. Similar patterns were evident in New Mexico and Arizona, namely numerically greater Mexican presence in the south with greater Anglo presence further north. Tucson (Arizona), for instance, remained predominantly Mexican, while Phoenix and Prescott grew more Anglo.[46]

* * *

6 Although the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo had guaranteed to Mexican people living in the southwestern territories “the enjoyment of all the rights of citizens of the United States according to the principles of the Constitution,”[47] it would be disingenuous to pretend that Anglos regarded Mexicans as their equals. The words of a Mexican diplomat at the time, Manuel Crescion Rejon, would prove prescient:

Our race, our unfortunate people will have to wander in search of hospitality in a strange land, only to be ejected later. Descendants of the Indians that we are, the North Americans hate us, their spokesmen depreciate us, even if they recognize the justice of our cause, and they consider us unworthy to form with them one nation and one society; they clearly manifest that their future expansion begins with the territory that they take from us and pushing aside our citizens who inhabit the land.[48]

7 But Mexicans living on the frontier were faced not just with an absence of hospitality, as Rejon had expressed it; they were often confronted with outright violence. Anglo newcomers ran Mexican ranchers off their lands in Texas and drove Mexicans out of towns in Texas and Arizona. During the California Gold Rush, which had attracted men from all over the world and from as far away as China, the Anglos, who outnumbered other groups, often harassed the Spanish-speaking miners as well as the Chinese. California was notorious for passing discriminatory laws, just one example of which was the Foreign-Miners Tax of 1850, which required any miner who was not an American citizen to pay heavier taxes on the yields from their mines.[49] To Mexicans who were treated as foreign miners despite having gained citizenship as a provision of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, this was obviously an outrage.

8 When Mexican miners resorted to armed revolt, Anglos often retaliated with disproportionate violence. During the Gold Rush years, “scores of Mexican miners were lynched and murdered.” Some Mexicans responded to Anglo depredations by turning to banditry, meeting violence with violence. Anglos answered by forming “vigilance committees,” particularly in California and Texas, and “lynching became a common outlet for anti-Mexican sentiment, justified, according to its adherents, as the only means of dealing with Mexican banditry.” But countless Mexicans “were lynched for minor crimes or crimes they had not committed at all. The Texas Rangers became infamous for their wanton killing and lynching of innocent Indians and Mexican Americans.”[50] Yet in American popular culture, the Texas Rangers have often been depicted as frontier heroes, while the role of Mexican banditry has been treated as if it were the norm. Neither depiction is historically honest.

9 In the face of frontier violence, Mexican Americans banded together for their own protection, often setting themselves apart in rural villages, ranchos, and barrios, i.e., urban enclaves with their own “stores, barbershops, Catholic chapels, funeral parlors, and even private schools.” Meanwhile, new immigrants from Mexico tended to settle in areas already occupied by Mexican Americans, reinforcing traditional lifestyles, and the newcomers often brought newspapers from the south that served to keep alive Mexican Americans’ interest in political developments in Mexico.[51]

10 However, by the 1880s, the character of the Southwest was beginning to change. Whites had largely “consolidated their political and economic hold on the region,” and with that all the latest elements of a national mainstream culture had begun to appear, from consumer products to fashion. Moreover, “Mexican Americans began to enter Anglo settings more frequently,” including in the “growing urban centers where Anglos enjoyed a significant majority.”[52]

11 The changing cultural landscape also helped shape Mexican Americans’ sense of their own identities in diverse ways. Some Mexican Americans still idealized Mexico as the beloved homeland and continued to see themselves as Mexican through and through. They tended to reject Americanization as a process that would produce a community that was “neither Mexican nor American but a corruption of both heritages.” Others claimed the United States as their only home but embraced a bi-cultural identity. They recognized the practicality of learning English, while advocating for the preservation of Spanish through programs such as bilingual education in public schools. “Finally, there were those who were completely Americanized … [and] who felt no attachment to Mexico, its institutions, or its culture.”[53]

10. Mexican Labor Builds a New Southwest

1 Between 1880 and 1920, the Southwest underwent a radical economic transformation, becoming a center of extractive industries such as mining and agriculture, both of which required large inputs of labor. The growth in these enterprises was made possible by the extension of transcontinental railroad networks into all regions of the United States, allowing for the distribution of raw materials and agricultural products to every corner of the United States. Mexico too embarked on railroad building, connecting Mexico City with the border states of northern Mexico. Mexican workers, bound for the Southwestern U.S. which was hungry for labor, could get there quite easily.[54]

2 Mexican labor was indispensable to the booming economic development of the late 19th century Southwest. “Mexican labor built, maintained, and repaired the railroads that forged the links between the Southwest and the urban markets of the Midwest and the East. … Mexican labor also made agricultural expansion in the Southwest possible.” Mexican workers cleared land and harvested cotton in Texas, planted and harvested sugar beets in the Great Plains, and harvested citrus in California. Forty percent of the fruits and vegetables produced in the American Southwest was accomplished largely thanks to Mexican labor. In addition, the region’s “mines and smelters, … government irrigation projects, road construction, cement factories, and municipal rail work all depended on Mexican labor.”[55]

11. Northward into the 20th Century

11.1 From 1900 through the Great Depression

1 Robust migration from Mexico to the United States continued into the early 20th century. Approximately 219,000 Mexicans migrated to the U.S. between 1910 and 1920. As a result, the Spanish-speaking populations of Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas doubled in size, while that of California quadrupled in size![56] Several factors prompted Mexicans to migrate to the U.S. during these years in previously unprecedented numbers. For one thing, Anglo-American investment in Mexico’s infrastructure destabilized the Mexican economy, destroying the livelihoods of Mexican laborers who were engaged in traditional urban occupations and forcing others off of communal lands. Secondly, the Mexican Revolution, a civil war characterized by a series of regional armed conflicts, lasting from 1910 to 1920, caused many Mexicans to flee the chaos and violence.[57]

2 The outbreak of World War I (1914–1918) also enticed Mexicans to migrate to the U.S. as the supply of immigrant labor from Europe was cut off, creating widespread labor shortages. In response, Mexicans fanned out across the country to provide labor wherever it was needed. When the U.S. entered the war belatedly in 1917, Mexicans helped supply the increased labor associated with the war industries. Some Mexican Americans volunteered for military service and fought in Europe.[58] Throughout the first decades of the 20th century, Mexicans began to show up in greater numbers in regions beyond the Southwest. By the 1930s, Mexicans were evident in substantial numbers in the Great Plains and the Great Lakes and as far away from the traditional borderlands as Pennsylvania and New York.[59]

3 The 1920s, or so-called Roaring Twenties after World War I, were years of prosperity and economic expansion, but the “good times” ended abruptly in 1929 when the stock market crashed, followed by the Great Depression which lasted for about a decade. The Great Depression brought hard times to almost everybody. But Mexicans and Mexican Americans were particularly hard hit. The need for labor dried up almost overnight and millions of people found themselves jobless during the 1930s. As the government enacted its first modest attempts at providing economic relief for the unemployed, public officials “throughout the Southwest and in such cities as Gary, Indiana; Detroit, Michigan; Toledo, Ohio, where there were large concentrations of Mexicans and Mexican Americans, … decided that it would be cheaper to send the Mexican[s] … back to Mexico,” rather than to provide them the same economic support as everyone else. “Thus, a system of repatriation began.”[60] Julian Samora and Patricia Simon’s extended description captures the cruelty and injustice of the system:

During the first four years of the 1930s, well over four hundred thousand Mexicans were repatriated to Mexico. Most of those repatriated Mexican citizens were legal residents of the United States; many were American citizens that is, Mexican Americans. Some had lived in this country thirty or forty years and had established their homes and their roots here. Many families were broken up, for in some cases either the father or mother, or both, were alien, but the children, having been born and raised in this country, were American citizens and allowed to stay while their parents were repatriated. To be sure, some Mexican aliens departed voluntarily, but those who were forcibly removed and those whose families were disrupted suffered enormous hardships during this period.[61]

11.2 World War II Era

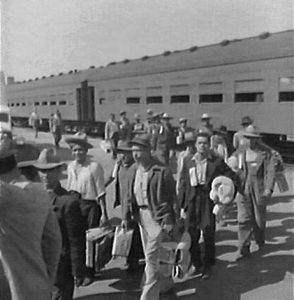

1 Significant immigration from Mexico did not resume again until the 1940s when the outbreak of World War II created economic conditions similar to those that had existed during World War I. The need for men to fight in the war and the need for workers in the war industries had drawn many laborers away from other essential work, in particular farm work. To address the farm labor shortage, the U.S. once again sought to import labor from Mexico. However, remembering the deportations of Mexicans from the U.S. in the 1930s and mindful, too, of the discriminatory tendencies of some U.S. states, the Mexican government insisted on negotiating worker protections around issues such as health care, wages, housing, food, and the number of working hours, as well as extracting assurances protecting Mexican nationals against discrimination. Understood to be part of Mexico’s contribution to the war effort, the so-called Bracero agreement was supposed to be primarily a temporary farm worker program although some braceros also worked on the railroads.[62]

2 More than 200,000 Mexicans entered the U.S. under the Bracero agreement during the war.[63] Unfortunately, despite the Mexican government’s efforts to secure a contract that protected the interests of Mexican workers, powerful farmer’s associations found ways to abuse the program. American “farmers continued to hire undocumented workers from Mexico,” which allowed them to circumvent provisions of the bracero agreement to the detriment of the undocumented. Moreover, “the bracero agreement [itself] undermined the wages of domestic farm workers, who were replaced by contract laborers from Mexico.” As Vargas has noted, “The flood of contract laborers and undocumented workers would contribute to canceling almost all of the accomplishments of Mexican Americans on the labor and civil rights fronts.”[64]

3 Meanwhile, Mexican Americans made significant contributions to the war effort. “The war production boom provided new opportunities for Mexican American women.” Although paid less than men, their pay in the defense industries was at least twice as much as the pay they had received in their previous jobs, and many were able to work “in areas previously closed to them because of gender discrimination.”[65] Moreover, nearly “a half a million Mexican Americans served in the armed forces,” and participated in combat in every theater of World War II from Europe and North Africa to the Pacific.[66]

4 Yet despite their service to the country overseas, Mexican Americans continued to face racism and discrimination at home. The story of Staff Sergeant Macario García of Sugarland, Texas is illustrative:

García … was one of a dozen Mexican Americans who received the Medal of Honor for acts of bravery in World War II. The Tejano received the award for his actions on November 20, 1944, near Grosshau, Germany. Despite García’s exemplary service fighting the Nazis in Europe, the Tejano returned to find … the unchanging and callous discrimination of Anglo-Texans. In September 1945, shortly after returning from Washington, DC, where he was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Truman, García was refused service in a restaurant in Richmond, Texas, because he was Mexican.[67]

5 García’s experience was nothing out of the ordinary. Time and again, Mexican American war veterans “found it difficult to obtain adequate health care or well-paying and meaningful work.” And Mexican Americans in general would have to struggle for decades against the indignities of “de facto second-class citizenship.” However, as was the case with Indigenous and African American war veterans, Mexican American veterans often returned home with a sense of newfound dignity and a greater willingness to stand up and fight for themselves and their communities.[68]

11.3 The More Things Changed, the More They Stayed the Same

1 The end of World War II ignited an unprecedented economic boom as U.S. industries turned from military production to the production of domestic consumer goods. Soldiers returning from the war easily found work—if they were White—whereas Mexican Americans and other racialized minorities often found the doors of opportunity closed as a result of the usual discriminatory social and economic practices that had always characterized life in the U.S.

2 Mexican Americans were also disadvantaged by the continuation of the Bracero Program, which was supposed to have been a temporary wartime program. The original rationale for the program had been to replace Mexican American farm workers who had been drafted or had volunteered in the armed services. However, big corporate growers, who were addicted to cheap labor, lobbied for the program’s continuance after the war. Many braceros simply remained as undocumented immigrants when their contracts expired, with the result that growers retained a ready pool of laborers, whose illegal status made them more susceptible to manipulation and who were willing to work for lower pay than returning Mexican American farm workers could have demanded.[69]

3 The continuation of the Bracero Program also inadvertently encouraged illegal immigration by raising the hopes of new braceros so that many more applied than could be accepted. Applicants who were rejected often immigrated illegally. Moreover, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) frequently colluded with growers, opening the border whenever growers clamored for workers. The INS even sometimes helped farmers recruit workers from among the undocumented entrants, who were allowed to become legalized as they worked. At the same time, by failing to recruit native-born farm laborers, and hiring braceros instead, growers were routinely violating the original Bracero agreement.[70]

4 By 1959, braceros were even working at non-agricultural jobs, such as “lumbering, trucking, light manufacturing, and ranching.” Employers felt no pressure to provide decent working conditions, and the “bracero wage” was becoming the norm for all agricultural workers, including native workers. And in direct violation of federal regulations, growers sometimes even used braceros to break strikes. In the meantime, even as powerful farming interests pressured the government to keep the labor coming from Mexico, nativists, labor unions, and even many long-established Mexican Americans were demanding that the U.S. government do something about the growing presence of undocumented workers in the labor force.[71]

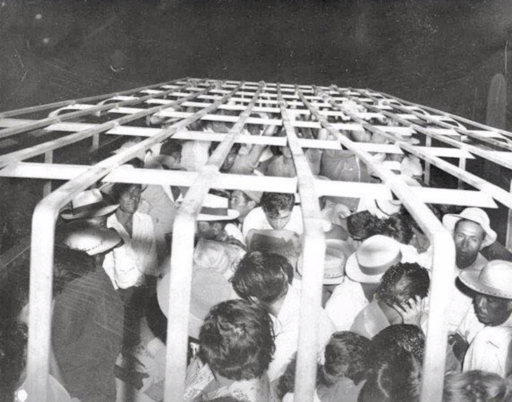

5 In 1954, in the face of an economic recession in which unemployment had doubled, the government finally responded in a heavy-handed way reminiscent of the mass deportations of the 1930s. In a highly publicized action known as Operation Wetback, federal agents sought to round up and deport undocumented Mexican nationals. Making few attempts to distinguish between American citizens of Mexican descent and undocumented Mexican nationals and with no recourse to due process, “this indiscriminate roundup caused families to be separated and children left behind.”[72]

12. Chicano Awakening

12.1 Identity

1 The 1960s and ’70s was a period of profound cultural, political, and social change in the United States. Many historically marginalized groups—Indigenous, Mexican, Black, and Asian—all mounted aggressive and sustained challenges to the systemic inequalities and institutionalized racism that had long plagued the nation.

2 Mexican Americans who came of age in the post-World War II years observed the growing prosperity of majority White communities and felt increasingly frustrated and disillusioned. Too often, their own communities continued to experience only persistent poverty, limited access to quality education, inadequate healthcare, and a lack of economic opportunities. Many of the most politically engaged Mexican Americans began to question whether the goal of trying to assimilate into mainstream society was a realistic one. Their elders had often assumed that assimilation was the best path to full and equal citizenship, but they had only been left further behind. Out of disillusionment, a new identity began to take shape—a Chicano identity—which in turn laid a foundation for the rise of a robust Chicano Movement, often referred to by participants at the time simply as el Movimiento.

3 But what is a Chicano? According to interpreters of the Chicano experience such as Maceo Motoya and Moctesuma Esparza, the word itself points to the indigenous roots of Mexican people. It is a reminder of the clash between Spain and the Aztec empire in the 16th century. According to this understanding, the word Chicano was derived from the root word for Mexico which is based on the name of the Aztec Indians, who called themselves Meshica, not Aztec, as the Spanish called them. However, the indigenous “sh” sound was written in 16th century Spanish as “x”—hence Mexica. According to Esparza, Chicano was simply a permutation of Meshica with the weak first syllable “me” dropped, leaving “shica” or “chica,” and that became Chicano—short for (Me)Chicano.[73]

4 While the word “Chicano” would eventually become popular among Mexican American civil rights activists in the 1960s, they were not the first Mexican Americans to adopt it. It was apparently used by Mexican immigrant workers as early as the 1920s. And in the 1940s, many second-generation Mexican Americans, especially the so-called pachucos, frequently self-identified as Chicano.

5 Pachucos were predominantly urban youth, living in the barrios of places like East Los Angeles and South El Paso. These young men and women (pachucos y pachucas), feeling alienated from both the dominant Anglo-American culture, as well as from the Mexican culture of their immigrant parents, rebelled against both by developing a street culture of their own making. This included a particular slang, or caló, and often a distinctive style of dress—known as a zoot-suit. First worn by young African Americans, a zoot-suit typically featured high-waisted pants with baggy legs, tapered tightly at the ankles, worn with a long coat with wide lapels, and topped off by a stylish pancake hat. Of course, not every pachuco was a zoot-suiter, as purchasing the suit required a substantial investment, and not every pachuco could afford a zoot-suit. At any rate “[b]oth pachucos and zoot-suiters called themselves Chicanos. Young Mexican Americans in the barrios who were neither pachucos nor zoot-suiters also referred to themselves as Chicanos after the 1940s.”[74]

6 In the 1960s, the term Chicano was popularized by a new generation—the Chicano Generation—some of whom had even gone through their own pachuco phase. Like the pachucos, this generation also pressed a counter-cultural agenda, but unlike pachucos, their rebellion would be a politically engaged one. “To be a Chicano in the 1960s and 1970s was to be an activist in the Chicano Movement.”[75]

7 What we are here calling “a Chicano Awakening” represented a profound generational shift involving a radical change in the way members of the Chicano Generation would come to define themselves as contrasted with the way their elders in the preceding “Mexican American Generation” had defined themselves. Chicano historian Mario García’s description of this contrast is worth quoting at length:

The Chicano Movement in its revisionist and oppositional interpretation of history stressed that Chicanos were fighting not only class oppression and ethnic and cultural discrimination, but also deep-seated racism. Earlier Mexican American civil rights struggles from the 1930s to the 1960s led by the Mexican American Generation used a “whiteness” strategy to argue that if people of Mexican descent were being recorded in the U.S. Census as “whites,” then there was no basis for discrimination and segregation of Mexicans based on race. The Chicano Generation eschewed such a strategy and noted that Mexicans had always been racialized in jobs, wages, housing, and education. The very term Mexican was racialized so that anything Mexican was considered by whites to be inferior. Chicanos emphasized this reality. They also argued that since they were a people of color, they not only needed to be proud of this but to combat racism as a people of color. The concept of racialization was an important recognition by the Chicano Movement and a way of challenging the mythic “melting pot.” If there were such a pot, why had Mexicans and Black people, for example, not been melted? It was because of racialization, the movement argued.[76]

8 While not discounting the heroic efforts of earlier generations of Mexican Americans—at labor organizing, challenging systemic discrimination, and fighting for educational rights—the new Chicanos faced the reality that these efforts had often failed or been only marginally successful. The Chicano Movement of the ’60s and ’70s would build on past legacies with renewed vigor and make unprecedented gains.

12.2 Huelga!: Organizing Farm Workers

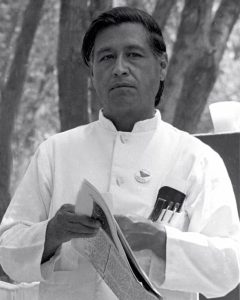

1 One of the most iconic achievements of the Chicano Movement was the successful effort to unionize farmworkers. In particular, the grape strike of 1965 centered in the San Joaquin Valley of California is often seen as the start of the Chicano Movement. The architects of this project were César Chávez and Dolores Huerta.

2 César Chávez was the first Chicano Movement leader to gain nationwide attention and is generally regarded as the Mexican American counterpart to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Moreover, Chávez was inspired by King’s philosophy of nonviolence as the best means of effecting change. Chávez understood from personal experience the hardships and suffering of migrant farmworkers. Indeed, his own parents had lost their farm during the Great Depression, forcing the family to become migrant farmworkers in order to survive. They had followed the harvest to California, lived in labor camps that lacked adequate sanitation, and César had even found it necessary to drop out of school in 8th grade to work full-time in the fields.[77]

3 Dolores Huerta, who in cooperation with César Chávez co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (known today as the United Farm Workers), was initially less well known to the general public than Chávez, but she has become better known in more recent years. As of this writing, Huerta is 93 and still active in the labor movement. In the 1960s, Huerta was as dynamic and effective a union lobbyist, spokesperson, and negotiator as anyone in the labor movement. Known by her adversaries in agribusiness as “the dragon lady,” she often went head to head with the lawyers of the powerful growers and extracted agreements that even Chávez himself might not have been able to get. Although Huerta didn’t grow up working in the fields, her father had been “a farmworker, miner, and union activist who also served in the New Mexico legislature.” Dolores had studied to become a teacher before she veered off of that course to become a union organizer.[78]

4 Chávez and Huerta got started as organizers in the 1950s working with the Community Service Organization (CSO), a Mexican American advocacy group that worked on issues related to voter registration, open housing, fighting school segregation, and police brutality. Eventually, becoming disenchanted by the CSO’s unwillingness to organize agricultural workers, Chávez and Huerta left the CSO and teamed up in 1962 to establish the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA). Chavez and Huerta went door-to-door in Delano, California, the heart of San Joaquin Valley agriculture, slowly organizing hesitant farmworkers, and by 1964, “the union had a few hundred members, an insurance program, and a credit union, as well as a newspaper, called El Malcriado.” In 1965, the union organized several small strikes which delivered higher wages to workers. However, “they failed to reach the union’s ultimate goal: recognition of the NFWA as the workers’ legal collective bargaining agent.”[79]

5 The beginning of the struggle against California’s most powerful growers came in September of 1965 when a rival union, the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) led by Filipino American activist Larry Itliong organized a series of walkout strikes among Filipino grape pickers. Itliong asked Chávez to join the strike, and an ambivalent Chávez, unsure whether the NFWA was financially secure enough to mount a big strike but hesitant about keeping his own people on the job in the face of the Filipino walkouts, put the issue to a vote. The NFWA, which by then had grown to 1,200 members, voted to join the Filipinos in solidarity and strike against Schenley Industries and DiGiorgio Fruit Corporation, two of California’s largest growers. The striking workers were met with the usual tactics of violence and intimidation on the part of the growers.[80]

6 In the spring of 1966, Chávez sought to bring national attention to the strike. Inspired by the nonviolent marches employed by Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in the South, Chávez organized a roughly 300-mile pilgrimage from Delano to the state capitol in Sacramento that lasted about 25 days.[81] Carrying a large flag with the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, the patron saint of Mexico, and flying the red farmworker’s flag with its black eagle, the marchers passed through one rural town after another singing “De Colores,” a song with religious origins. Their numbers grew each day, and they attracted national media attention.[82]

7 Meanwhile even before the march from Delano reached Sacramento, Dolores Huerta had successfully negotiated a UFWOC contract with Schenley, and in time, other growers signed contracts as well. That summer, NFWA and AWOC merged to form the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee (UFWOC), creating a much larger union with more resources and preparing to take on the largest grower of table grapes in the state, Giumarra Vineyards Corporation, which remained absolutely opposed to unionization.[83]

8 While Chávez organized the workers in the field, Huerta traveled the country organizing for the union, negotiating and lobbying for UFWOC in Sacramento and Washington, DC, and directing UFWOC boycotts.[84] In an effort to increase the pressure on Giumarra, UFWOC called for a nationwide boycott of Giumarra grapes. When Giumarra sought to get around the boycott by illegally selling their grapes using the labels of other grape companies, UFWOC extended the boycott to all table grapes.[85] As the struggle wore on, public awareness of the farmworkers’ cause grew. Politicians such as then presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy and Senator Walter Mondale recognized and supported the farmworkers’ cause, as did prominent Black civil rights leaders such as Ralph Abernathy.[86]

9 In the end, the fight to improve the lives of farmworkers was a long and bitter one with small victories and numerous setbacks along the way. The fight over grapes alone, which began in 1965 was not resolved until 1970 when “Lionel Steinberg, the owner of Freedman Farms, signed a contract with the farmworkers union and a union label was placed on his table grape crates.” Grapes with the union label commanded higher prices, and “[i]t wasn’t long before other grape growers, tired of their fruit rotting in warehouses, signed similar contracts and received the now coveted union label.” When Giumarra finally came to the negotiating table and brought all the other table grape companies along, “Dolores Huerta negotiated a settlement … that provided higher wages and benefits for scores of workers, ending the most successful consumer boycott in labor history.”[87]

10 In 1972, UFWOC was incorporated into the larger union movement as the United Farm Workers of America, and the wages and working conditions for farmworkers continued to improve. Between 1970 and 1974, workers saw a 70% wage increase, and the introduction of health care benefits, disability insurance, pension plans, grievance procedures, the elimination of the backbreaking short hoe, the banning of many pesticides, and the introduction of unemployment benefits.[88]

* * *

11 Unfortunately, throughout the late 1970s and the 1980s, the UFW failed to make the necessary transition from a social movement to a functional labor movement in no small part due to missteps on the part of César Chávez himself who became increasingly inflexible and dictatorial as time went on. Internal divisions, including leadership conflicts and disputes, weakened the organization, and the UFW encountered difficulties in retaining existing collective bargaining agreements and securing new contracts. The UFW also experienced a decline in membership and public attention and support began to drift in the direction of other social and political concerns. However, despite its decline, the UFW continued to exist and engage in advocacy efforts. It undertook various initiatives, such as supporting labor legislation and continuing to raise awareness about farmworker issues even as its ability to achieve large-scale results diminished compared to its earlier years.[89]

12.3 New Mexico Land Grants Movement

1 Another charismatic pioneer of the Chicano Movement was Reies López Tijerina. Born in Falls City, Texas in 1926, Tijerina would go on to lead a fight on behalf of the Hispanos of New Mexico “to regain the community land grants that the federal government and land corporations had taken from them after the War with Mexico.” The land dispossession that followed the war, Tijerina claimed, had clearly violated the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. “Tijerina traveled throughout New Mexico” during the early ’60s “organizing a land grant association called La Alianza Federal de Mercedes Libres (Federal Alliance of Free Land Grants).” The Alianza sought to educate the heirs of all Spanish land grants regarding their rights under the Guadalupe Hidalgo Treaty.[90]

2 But whereas Chávez and the United Farm Workers had held firmly to a philosophy of non-violence, Tijerina’s approach was much more militant. In October 1966, members of the Alianza briefly occupied Echo Amphitheater Park in the Kit Carson National Forest, claiming that it lay in the Tierra Amarilla land grant, which had been unlawfully taken by the government. To dramatize the event, Tijerina proclaimed the establishment of a city-state, the Republic of San Joaquín del Cañón de Chama, and the Alianza staged a series of “camp-ins.” When the Forest Service responded by sending law enforcement officers to arrest the Alianza members, Tijerina and several followers arrested the rangers for trespassing and ordered them out of the camp. Tijerina and several others were subsequently arrested on federal charges.[91]

3 After the Kit Carson National Forest episode, the Alianza continued its militant rhetoric and convened organizational meetings in Albuquerque. Claiming that the Alianza was “inciting violence, New Mexico District Attorney, Alfonso Sánchez, and State Police Chief Joseph Black ordered the Alianza not to hold any further meetings.” Denouncing the Alianza as radical agitators, state authorities began arresting suspected Alianza members[92]

4 On June 5, 1967, in “a desperate attempt by the Alianza to force authorities to release seven of their jailed members charged with illegal assembly and to make a citizen’s arrest of District Attorney Sánchez,” Tijerina led a raid on the Tierra Amarilla Courthouse (in Rio Arriba county about seventy-five miles northwest of Santa Fe). A violent confrontation ensued, resulting in shots being fired on both sides. Several people, including law enforcement officers and raid participants, were wounded. Ultimately, Tijerina and his supporters were outnumbered and forced to retreat. Tijerina and the Alianza members involved fled into the mountains, and the state of New Mexico launched the largest manhunt in the state’s history[93]

5 Tijerina was eventually captured, charged, and found guilty of assaulting U.S. Forest Rangers and appropriating government property during the Kit Carson National Forest affair. He served two years in jail, and the Alianza disbanded and reorganized as La Confederación de Pueblos Libres (Confederation of Free People). Despite the demise of the Alianza, Tijerina remained undeterred in his efforts to speak out about the land grants issue and seek justice for New Mexico’s Hispanos who had been dispossessed.[94]

12.4 Chicano Student Movement

12.4.1 Introduction

1 Leaders like Chávez, Huerta, and Tijerina inspired a whole generation of young urban Mexican Americans. Beset by feelings of alienation in their schooling and frustrated by chronically high levels of educational failure and the failure of schools to meet their educational needs, Mexican American students in the mid-1960s awakened to a new Chicano identity. In the decade of the ’60s, high school dropout rates for Mexican Americans were among the highest of any group in the U.S. The median grade attainment was only 8.1, compared to 9.7 for other non-Whites and 12.0 for Anglos. A major factor holding young Mexican Americans back was low expectations and pure neglect on the part of the largely Anglo teaching force in places like East Los Angeles and other urban school districts with large Mexican American populations.[95] In response, young Chicanos began to create advocacy groups on college campuses and in high schools, first in the Southwest and eventually across the country.

12.4.2 Chicano Youth Leadership Conference in Malibu

1 Undoubtedly, one of the most consequential events of the decade was the Mexican American Youth Leadership Conference (later called Chicano Youth Leadership Conference, CYLC) held in April 1966 at Camp Hess Kramer in Malibu, California. The venue was unusual in that Hess Kramer was a Reform Jewish youth camp run by a Rabbi named Alfred Wolf. But Wolf was an interfaith pioneer and a longtime ally of Los Angeles Chicanos. The purpose of the conference was to get the best and brightest Mexican-American high schoolers in Southern California together for a weekend of introspection, growth, and leadership training[96]

12.4.3 Young Citizens for Community Action and Brown Berets

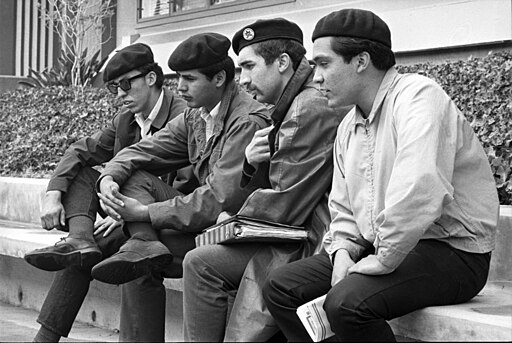

1 In the 1966 CYLC Conference, the conversations had continued beyond the conclusion of the conference, “and a group of six of the attendees, including David Sánchez, created Young Citizens for Community Action (YCCA), whose mission was “to reform the local educational system through political action and electoral participation.” A couple of years later, YCCA members began identifying as “Brown Berets.” Drawing inspiration from the Black Panther Party which had adopted a para-military image in an attempt to deter police harassment in the Black community, the Brown Berets dressed in military khakis and brown berets with a distinctive pentagonal patch bearing the words “La Causa” above the image of two bayoneted rifles and a cross. But while the group was often perceived as a militant organization, their militancy was often exaggerated. Indeed, their usual activities focused primarily on community organizing, education, and advocacy for civil rights. They were, however, strongly committed to trying to protect the Mexican American community from police brutality and holding police accountable for their actions.[97]

12.4.4 Mexican American Youth Organization and La Raza Unida

1 The following year, at Saint Mary’s, a small liberal arts college in San Antonio, Texas, five Chicano student activists—José Ángel Gutiérrez, Willie Velásquez, Mario Compean, Ignacio Pérez, and Juan Patlán founded the Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO). MAYO would become instrumental in the fight to address student grievances in Crystal City, Texas, a small farming and ranching community one-hundred miles southwest of San Antonio. Mexican American students in Crystal City had become fed up with the discrimination prevalent in local schools, characterized by bigoted teachers, a school wide ban on speaking Spanish, and the lack of transparency in selecting students for homecoming king and queen, cheerleading, and other honors, typically awarded to Anglo students despite the fact that Mexican Americans comprised a majority of the school.[98]

2 In December 1969, inspired by the Los Angeles Student Walkouts the year before, “Crystal City high school students walked out of their classrooms, eventually leading to a districtwide boycott. School board officials caved in a month later, acquiescing to student demands,” demonstrating to the Mexican American community “that they had strength in numbers and that political power was a possibility.”[99]

3 Gutiérrez and Compean soon seized the moment by establishing the Raza Unida Party (RUP) and starting to organize voters to challenge the Anglo establishment in South Texas. Although MAYO and the RUP did well at getting Mexican Americans registered to vote, they weren’t as successful at getting Mexican Americans to the polls, especially in urban areas. However, their efforts were moderately successful in getting Mexican Americans in seats on Texas school boards.[100]

12.4.5 East Los Angeles Student Walkouts

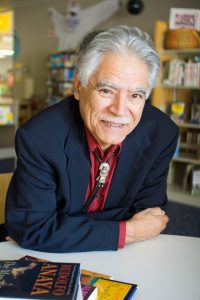

1 In the mid-1960s, Sal Castro, who had played a major role in mentoring Chicano Youth leaders through the annual Chicano Youth Leadership Conferences, emerged as one of the most influential Chicano educators in California. A dedicated teacher and activist, Castro played a crucial role in advocating for educational equity and empowerment of Chicano students. Best known for his leadership in the 1968 East Los Angeles high school walkouts, Castro worked tirelessly to raise student awareness regarding their Mexican heritage, encouraging them to protest the discriminatory practices, unequal treatment, and lack of resources in their schools.[101]

2 In March of ’68, after months of preparation by student organizers, many of whom had attended the annual CYLC events, more than 10,000 students in several schools across East Los Angeles walked out and refused to return. Students continued to walkout every day for two weeks as students pressed their demands for the elimination of discriminatory school policies and racist teachers, a curriculum that addressed Mexican American history and culture, and more Mexican American teachers and administrators.[102]

3 The Los Angeles police reacted to the walkouts in their usual heavy-handed way and were caught on film brutally beating students. Moreover, thirteen “organizers, student activists, … members of the Brown Berets, antipoverty workers, publishers of a local Chicano newspaper, and Lincoln High School teacher Sal Castro” were arrested, “and charged with conspiracy to disturb the peace.” Castro was fired from his job, but “[a]fter a series of dramatic sit-ins and protests, the school board reinstated [him] and all charges against the [thirteen defendants] were eventually dismissed.”[103] “The walk outs eventually led to meetings with parents and administrators and many of the students’ demands were met.”[104]

12.4.6 El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán

1 Another nexus of the Chicano Movement was Denver, Colorado, where Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales was busy advocating a new, nationalistic Chicano identity and pushing for community self-determination. Gonzales was born in Denver in 1928, placing him, along with Tijerina, Chávez, and Huerta, squarely in the Mexican American generation. Like many of the Mexican American generation, Gonzales began his career as an activist in the belief that assimilation was the way to acceptance in American society. In the late 1950s, Gonzales made his mark in Denver politics by registering voters for the Democratic Party, and in 1960, he helped turnout Mexican Americans to vote for John F. Kennedy. He subsequently held leadership positions in various government programs, including Denver’s War on Poverty program, which was part of President Lyndon Johnson’s antipoverty initiative. However, as time went by, Gonzales lost faith in the promise of assimilation and in electoral politics as a vehicle for change. He began to see the Democratic Party as happy to have Mexican American votes but failing to field Mexican American candidates or to truly take an interest in the issues and concerns of the Mexican American community.[105]

2 In 1966, Gonzales founded an organization called Crusade for Justice which provided the Chicano community benefits such as job training, a food bank, and a bilingual school for children that encouraged cultural pride. Crusade for Justice also protested against police brutality and racism in the media. In March 1969, Crusade for Justice organized a conference in Denver, Colorado, which remains today perhaps the defining event in the history of the Chicano Movement as a movement—the Chicano Youth and Liberation Conference. The meeting resulted in the drafting of El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán.[106]

3 El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán was a revolutionary indigenous manifesto and is perhaps the clearest and most succinct statement of Chicanismo, or the cultural consciousness underlying the Chicano Movement. Authored by Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales, Juan Gómez-Quiñones, and poet Alberto Baltazar Urista Heredia, better known simply by the pen name, Alurista, the manifesto opened with a preamble by Alurista. It read (in English translation):

In the spirit of a new people that is conscious not only of its proud heritage but also of the brutal “gringo” invasion of our territories, we, the Chicano inhabitants and civilizers of the northern land of Aztlán from whence came our forefathers, reclaiming the land of their birth and consecrating the determination of our people of the sun, declare that the call of our blood is our power, our responsibility, and our inevitable destiny.

We are free and sovereign to determine those tasks which are justly called for by our house, our land, the sweat of our brows, and by our hearts. Aztlán belongs to those who plant the seeds, water the fields, and gather the crops and not to the foreign Europeans. We do not recognize capricious frontiers on the bronze continent.

Brotherhood unites us, and love for our brothers makes us a people whose time has come and who struggles against the foreigner “gabacho” who exploits our riches and destroys our culture. With our heart in our hands and our hands in the soil, we declare the independence of our mestizo nation. We are a bronze people with a bronze culture. Before the world, before all of North America, before all our brothers in the bronze continent, we are a nation, we are a union of free pueblos, we are Aztlán.

Por La Raza todo. Fuera de La Raza nada.

4 Following the preamble, El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán was organized into three sections. Section 1 asserted that the plan was grounded in nationalism as the key organizing principle. While not articulating in detail everything this would entail, we can understand nationalism as embodying the ideology through which any nation defines itself—a nation being a group of people united by shared cultural features, including things like myths, religious beliefs, and language, as well as a belief in the right to territorial control over a national homeland. The Chicano people, or La Raza (the race), a term the manifesto also uses in several places, is imagined as having historically been situated in Aztlán, a place in the American Southwest from which, according to Aztec (or Mexica) legend, the Mexica migrated before settling in the Valley of Mexico.

5 Section 2 of the manifesto outlined organizational goals to include: the achievement of economic control, education relevant to Chicanos, institutions that serve the people, self-defense, maintenance of cultural values, and political liberation. Finally, Section 3 laid out proposed actions, including disseminating the plan widely, organizing walk-outs in schools on Mexican Independence Day (September 16th) to demand complete revision of the educational system, defending the community, and building an independent nation, economy, and political system. The document ended by emphasizing that El Plan Espiritual de Aztlan is a plan of liberation.

6 As Maceo Montoya has noted, “El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán was a radical document. To read it today is to get a glimpse into the mindset of Chicano youth hungry for revolutionary change.” However, “the concept of Chicano nationalism remained ambiguous in the overall Movement. Some viewed it as a separatist agenda, a literal call for a Chicano homeland … separate from the Anglo-dominated United States.” Others read it more metaphorically as expressing a spiritual aspiration, a desire for a greater measure of self-determination and control over Chicano communities, education, and the political process, “a call for agency rather than passivity, pride rather than shame, hopefulness rather than helplessness.”[107]

12.4.7 Student Movement in Higher Education

1 In the 1960s, more Mexican Americans than ever before were attending colleges and universities thanks in part to federal programs such as the Educational Opportunity Program (EOP), which actively recruited Mexican Americans, and the GI Bill, which assisted veterans. Inspired by el Movimiento and the larger civil rights movement generally, Mexican American college students nationwide became politically engaged and created student organizations on campus dedicated to making institutions of higher learning responsive to minority students. In the spring of ’68, shortly after the East Los Angeles student walkouts, Chicano students at San José State College expressed their disapproval of the status quo in California institutions of higher education by staging a walkout during the graduation ceremony.[108]

2 As the fall of ’68 rolled around, Chicanos joined a coalition of student groups organizing as the Third World Liberation Front (TWLF) and representing diverse ethnic minorities on campus including Blacks, Chicanos, Chinese and other Asians, Native Americans, and Philipinos. The TWLF staged a nearly five-month-long strike, from November 6, 1968 until March 21, 1969, at San Francisco State and the University of California at Berkeley to protest the perennially Eurocentric fixation of institutions of higher education in the U.S. and to demand a more balanced mix of ethnic studies programs, the hiring of more minority faculty, and the admission of more ethnic minority students at colleges and universities.[109] The protests led to violent clashes between students and police, but in the end, the strikes led to the creation of the first Ethnic Studies Department in the country, at Berkeley.[110]

12.4.8 El Plan de Santa Bárbara

1 In April 1969, just a month after the Chicano Youth and Liberation Conference in Denver, a group calling itself the Chicano Coordinating Council on Higher Education (CCHE), hosted a three-day conference at the University of California at Santa Barbara. The goal of the conference was to develop a blueprint for Chicano studies programs in colleges and universities throughout the U.S. The result was a 155-page document called El Plan de Santa Bárbara. The Plan emphasized the importance of community control in Chicano education and the necessity of Chicano political independence while establishing the foundation for the Chicano student group Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA).[111]

2 MEChA would go on to become a national organization with chapters in colleges and universities across the country, uniting purely local groups such as the Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO), the Mexican American Student Association (MASA), and others. It had three main goals: 1) to link the university with the Chicano community in order to both serve student needs and form alliances with local Mexican American groups; 2) to recruit Mexican Americans and promote the ideology of Chicanismo, emphasizing, in particular, the importance of giving back to family and community; and 3) to encourage the creation of Chicano Studies and support services that would be relevant to Chicano students. [112]

* * *

3 During the 1970s, thanks to the Chicano Student Movement, more Latinos would be attending colleges and universities than ever before “and they would eventually establish Chicano and Latino studies departments at over 160 universities.”[113]

13. Mexican Americans and the New Immigration

1 Despite its many achievements, by the end of the 1970s the Chicano Movement had just about run its course. In 1983, the Los Angeles Times ran an article reporting that while a plurality of Mexican Americans identified as Latino, only a small minority (about 4%) were willing to embrace the term Chicano.[114] Of course, self-identified Chicanos had probably never been more than a small minority of the Mexican American population, representing only the most politically engaged. Nevertheless, like all the other ethnic civil rights movements, the momentum of the Chicano Movement eventually stalled.