5 Germans

1. Early German Migration to British North America

1 Unlike England and France in the 17th and 18th centuries, there really was no unified Germany until the Wars of German Unification (1866–1871). Instead, in the 17th and 18th centuries, the lands that would eventually become Germany were divided into a patchwork of small states and principalities, each with its own ruler and independent government. These fragmented territories were often marked by political rivalries and religious conflicts, with German princes vying for power and influence. This constant instability—political, economic, and social—compelled some adventurous German-speaking people to leave their homelands and cross the Atlantic, seeking brighter futures in British North America.

2 As early as 1608, eight Germans—five glass makers and three carpenters—had been among the first settlers of Jamestown. In 1621, four millwrights from Hamburg, Germany, arrived in Jamestown as well. And by the mid-1600s, Germans had settled in Virginia in even somewhat greater numbers, attracted by the tobacco trade.[1] However, those first Jamestown Germans are merely incidental to the story of German America, as there weren’t enough of them to constitute a significant ethnic German community. For the most part, they were assimilated into the English community.[2]

3 Gradually, German-speaking people would settle in modest numbers in all the colonies from Maine to Georgia. As for the first Germans in New England, a few arrived with the founders of the Massachusetts Bay colony in 1630; however, overall New England never attracted a very large German population. In fact, until 1683, the largest population of Germans in colonial America was in the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam, which was later taken over by the English and renamed New York.[3]

4 By far the largest concentration of Germans in the British colonies would eventually settle in Pennsylvania and its neighboring colonies. The first permanent German settlement in the colonies was Germantown, Pennsylvania, situated about five miles northwest of Philadelphia. Germantown was initially founded in 1683 by thirteen Mennonite families from Krefeld (in western Germany near the border with Holland). The Mennonites had been drawn to the colonies by the advertising of William Penn, the English writer, religious thinker, and influential Quaker who founded the Province of Pennsylvania based on a firm belief in religious tolerance. These original families were followed soon after by an influx of more Mennonites and some Quakers. Later, German settlers from various other religious groups, including Moravians, Schwenkfelders, Dunkers, and Waldensians, the so-called “sect people,” would come to settle in Pennsylvania, as well as Lutherans and Calvinists, also known as “church people,” who comprised the vast majority of colonial era Germans.[4]

5 Germantown soon earned a reputation for its wide variety of tradesmen, including carpenters, locksmiths, shoemakers, tailors, and weavers.[5] The weavers of Germantown produced so much fine linen that a textile store was opened in Philadelphia. In 1690, William Rittenhouse established the first paper mill in the colonies, and in 1710, he established a second one. Germantown later became one of the most important sites of publishing. Christopher Sauer, who immigrated in 1724, founded a printing house that became the largest in the colonies. Sauer published the first successful German newspaper and the first Bible ever printed in the American colonies, a 1743 German edition.[6]

6 Germantown also made a mark in the social history of the colonies in 1688, holding “the first public protest against slavery in North America [when] the German Quaker assembly passed a resolution condemning slavery.” Unfortunately, when the resolution was put forward for discussion at a meeting of the English Quakers, they were too timid to take a position, as the resolution entailed the implication that goods produced by practitioners of slavery ought to be boycotted, and the English Quakers were swayed by economic interests over moral principles.[7]

7 Throughout the 17th century, German migrants to colonial America consisted mainly of radical Pietists like the Germantown founders, but their numbers were actually quite small. At the beginning of the 18th century, for instance, Germantown itself still had only about 250 inhabitants. However, beginning in 1709, a wave of mass migration began that would bring German immigrants to the American colonies in unprecedented numbers.[8]

2. Palatine Exodus

1 Beginning in 1709, Germans in the Palatine region began to look to the American colonies for relief from the dire circumstances of their desperately poor lives. At the time, the Palatinate, or in German, the Pfalz, encompassed parts of the present-day German states of Rhineland-Pfalz in southwestern Germany and southwestern Hesse. The winter of 1708–1709, known as the Great Frost, was a disaster for much of Europe. It had been the coldest European winter in 500 years. It had had a devastating impact on crops and livestock,[9] and the agricultural crisis that it created, together with the ever-present threats of armed conflict and religious persecution that plagued life in the Pfalz, compelled a significant number of Palatine families to flee their poor villages. Lured by “rumors of free passage and free land to be granted by British authorities … would-be emigrants crowded the Dutch ports and the outskirts of London.”[10]

2 While it is difficult to settle on a consistent number regarding just how many Germans immigrated to the American colonies during the Palatine Exodus, the roughly 2,100 people who survived the voyages of 1710 may have represented “the largest single immigration to America in the colonial period.”[11]

3 At any rate, important as the mass migration from the Palatinate may be to the story of German colonial immigration, not all 18th century German immigrants came from the Palatinate. Overall, German immigrants represented many quite distinct subgroups and came from different regions of Germany with differing religious and cultural values. Large sections of Pennsylvania, Upstate New York, and the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia attracted German Lutherans or German Calvinists. Others belonged to small religious sects such as the Moravians, Mennonites, Amish, and Quakers. Finally, after the War of 1812, German Catholics began arriving in significant numbers.[12]

3. Prominence of German Settlement in Pennsylvania

1 From roughly 1717 on, and particularly between 1730s and the American Revolution, German immigration only intensified, with 70 to 80 percent of colonial German immigrants arriving in Philadelphia and settling in Pennsylvania.[13]

2 By the time of the American Revolution, fully one-third of all Pennsylvanians were German. By comparison, the English constituted another one-third, and the remaining one-third consisted of a mix of various other ethnic groups. In fact, the German population of Pennsylvania was so large that Benjamin Franklin feared the English in Pennsylvania would come to be so outnumbered that the English language would not be preserved and the governing of Pennsylvania would become a difficult affair. The Germans thus became, by virtue of their visible numerical presence, perhaps the first immigrant group to attract widespread prejudice from the Anglo inhabitants of colonial America. Benjamin Franklin even went so far as to suggest that there was a significant color line that separated the English from the Germans, declaring that the Germans “will never adopt our language, any more than they can acquire our complexion.” Franklin further disparaged the Germans for their clannishness and their lack of refinement.[14]

3 Other Anglo-Americans complained about their “total lack of education.” It was true that as many as a quarter of all Germans in the colonial era were illiterate, as they had come from German principalities offering no compulsory schooling. This situation led the governor of Pennsylvania to support “a plan to establish charity schools among the Germans.” Indeed, in the 1750s–1760s, Anglo authorities opened schools that included German American children, but Christopher Sauer, the first German-language printer and publisher in North America, denounced these schools as “having only a political purpose,” namely to interfere with the language, culture, and religion of the Pennsylvania Germans, and thus to Anglicize German American children. The German community subsequently resolved “to establish their own schools to preserve their German heritage,” and that brought about “the demise of the so-called charity schools.”[15]

4 By 1752, the Pennsylvania Germans numbered about 100,000—of whom an estimated 60% were Lutheran, 30% Reformed, and 10% sectarians. A small number were “clergymen, teachers, doctors, businessmen, and artisans, but the majority were … burghers and farmers … with little or no education.” But despite their humble status, they typically embraced “a strong sense of family, a deep religious faith, and a love and pride in their German heritage.”[16]

5 The typical farm family occupied a house located on a hillside in a wooded area. “A dated stone, or a date painted or carved into the wooden frame [of the house] would indicate the name of the owner and the year of construction, as was the custom in Germany. Roofs generally were covered with tile.” Outside might be a bakehouse and a smokehouse for the preparation of German-style breads and meats. A barn, constructed with fieldstone and framed in wood following architectural forms prevalent in southwestern Germany, would have been essential. “Most farms also had a garden, an orchard, and a beehive.” As might be expected, “food customs reflected those of Germany as well. A typical meal consisted of fresh wurst, roast pig, apples, geese cakes, beer, and molasses candy.”[17]

6 As for German families, they were usually large, and everyone worked, even the children. Moreover, German farmers, once settled, rarely moved unlike many Anglo farmers who seemed to have a penchant for moving continually westward. As a result, it is not surprising to find Pennsylvania farms today that have been in the same family since before the American Revolution.[18]

4. German Americans and the American Revolution

1 The Pennsylvania Germans held diverse political views. The sectarians were largely conscientious objectors and pacifists. As a matter of religious conviction, they refrained from military affairs and participation in politics, and some even refused to pay taxes. However, they made up only 10% of the Pennsylvania Germans, so while the sectarians took an anti-war stance when the American Revolution broke out, members of the larger religious denominations, the Lutheran and Reformed communities, had no reservations about military service, and many Pennsylvania Germans played major roles in the American Revolution, as did Germans throughout the colonies.[19] There were a number of German American regiments in the Continental Army and a significant number of German American officers. One notable example was Peter Muehlenberg, a Lutheran pastor from a prominent Pennsylvania family. Muehlenberg commanded the 8th Virginia Regiment and after the founding of the Republic, served several terms in the House of Representatives and briefly in the Senate.[20]

2 Significantly, George Washington’s bodyguard unit—consisting of 53 soldiers and 14 officers—were all German Americans.[21]

5. German Americans and the New Republic

1 The first U.S. Census, conducted in 1790, revealed the new United States to be already becoming a multicultural society, albeit one with a large dominant Anglo-American majority. People of English descent made up 2.3 million of the nearly 3.9 million inhabitants, or nearly 60% of the total. German Americans made up the second largest ethnic group at 350,000, or 9% of the population; however, two centuries later, German Americans would comprise 25% of the population, reflecting the massive tide of German immigrants that would eventually come to the U.S. At any rate, in 1790s, German settlement patterns were becoming clear. As indicated earlier, the center of German America lay in Pennsylvania, where 33.3% of the inhabitants were of German heritage. [22]

2 Other states with significant German American populations included: Maryland (11.7%), New York (8.2%), New Jersey (9.2%), W. Virginia & Virginia (6.3%), N. & S. Carolina (9.7%), and Georgia (7.6%). German Americans had also moved in large numbers into Kentucky and Tennessee (14%). Wherever German American communities thrived, characteristically German religious and secular institutions sprang up as well to meet their own particular needs. [23]

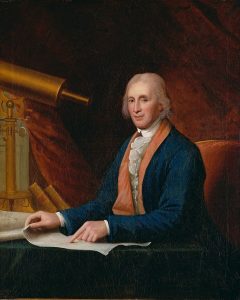

3 Having taken an active role in the struggle for independence, German Americans emerged as a group deeply invested in politics, governance, and the establishment of institutions that would put the new Republic on firm foundations. One example was David Rittenhouse, the great-grandson of William Rittenhouse, who had established the first paper mill in the colonies. David Rittenhouse served on the commission to establish the first U.S. Bank, and he was the first director of the U.S. Mint.[24]

4 Rittenhouse resembled Benjamin Franklin in the breadth of his interests, not only in politics and governance, but as a scientist and inventor. He was an “astronomer, … clockmaker, mathematician, surveyor, [and] scientific instrument craftsman,” as well as a “public official.” He was a member of the American Philosophical Society and served for a time as its librarian and secretary. From 1791 to 1796, following Benjamin Franklin’s death in 1790, Rittenhouse served as president of the society. Among his other political activities was the founding of Democratic-Republican Societies in Philadelphia, intended to promote republicanism and democracy and fight aristocratic tendencies in the new nation. [25]

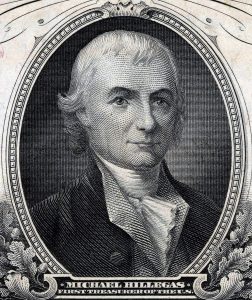

5 The distinction of being the first U.S. Treasurer also goes to a German American, Michael Hillegas, the son of German immigrants. Before the American Revolution, Hillegas had “acquired a considerable fortune from sugar refining, iron manufacturing, and banking, as well as from family businesses” During the Revolutionary War, from 1775, Hillegas served as Treasurer of the United Colonies, a position he continued to hold after the war ended in 1783, until Congress created the Treasury Department in 1789.[26]

6 There were German Americans among the first members of Congress, too. For example, Frederick Augustus Muehlenberg, brother of Peter Muehlenberg, having served in various capacities in the Pennsylvania Assembly, became the first Speaker of the House in the First Congress. He then went on to serve terms in the next three Congresses. Among other German American members of Congress were men such as Simon Driesbach, Charles Schumacher, and Michael Leib. German Americans who served as governors included Johan Adam Treutlein in Georgia and Simon Snyder in Pennsylvania. In fact, by 1942, twelve of the first twenty-seven governors of Pennsylvania had been German American.[27]

6. Political Leanings in the New Republic

1 In the 1790s, after the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, the outlines of a two-party system had already begun to take shape in the new United States of America. The Federalists, led by prominent figures such as Alexander Hamilton and John Adams, supported a strong central government and favored policies for the promotion and protection of U.S. commerce and industry. The Federalists were strongly pro-British and tended to be anti-French, especially with respect to the French Revolution. In contrast, the Democratic-Republicans (or Republican Party, for short) was established by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison and advocated instead a limited central government, strong deference to states’ rights, and support for agrarian interests and free trade. The Republicans were also sympathetic to French aspirations for liberty as expressed by the French Revolution.[28]

2 Many German Americans aligned themselves with the Republican Party in opposition to the Federalists. According to Don Tolzmann, the Federalists’ vision of government favored “the privileged, the wealthy, and the well-born.” Federalists also tended to be “mainly of English descent” and to openly express nativist fears that the Anglo element in America might be diluted by unrestricted immigration. German Americans were thus naturally suspicious of the Federalists.[29]

3 The Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 that were passed with strong Federalist support during the presidency of John Adams, only confirmed German American suspicions. Seeking to restrict immigration and limit criticism of the government, the Acts created a sense of hostility towards immigrants. Many German Americans, feeling targeted, became disillusioned with the Federalists and aligned themselves with the Republican Party, which opposed the Alien and Sedition Acts as destructive to civil liberties. The German American press became largely pro-Jefferson in the early 1800s, and “German Americans … swung overwhelmingly behind Jefferson for the election of 1800.” The Jeffersonian Republican Party would become the basis for the emergence of the Democratic Party during the first half of the 19th century, and most German Americans would remain Democrats “until the question of slavery caused the old parties to disintegrate, resulting in a new political alignment in the 1850s.”[30]

7. More Small Waves Before the Great Flood

1 The American Revolution and the economic depression that followed, along with the French Revolution (1789–1799) and the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), dampened immigration to North America for roughly 50 years. According to Walter Kamphoefner, “[a]lthough German immigration never stopped entirely, it was seriously curtailed.” Interestingly enough, it was another climate event that kicked off the first substantial 19th-century wave. On April 11, 1815, on an island east of Java in Indonesia, the violent eruption of the volcano Tambora sent volcanic ash and dust into the atmosphere where it encircled the earth, “darkening the sun and lowering temperatures in the northern hemisphere.”[31]

2 The year 1816 became known in New England as “Eighteen Hundred and Froze to Death,” and, more generally, as “the year without summer.” New England saw “repeated hard frosts, subfreezing temperatures, and snowfalls” throughout the summer, which killed off much of the region’s harvest.[32] Meanwhile, “[s]now fell in June in Germany; … grain failed to ripen, and prices in France and Germany reached levels that were not exceeded in the whole next century.” Then, just as they had done at the time of the Great Frost over a century earlier, thousands of people from the Palatinate in southwest Germany made their way to America hoping for better circumstances. Nevertheless, this wave subsided after a few years as the agricultural crisis passed and food prices returned to normal.[33]

3 By 1830, there was an unmistakable German-American settlement triangle in the U.S. with its three corners located in New York, Ohio, and Virginia. But German immigration in the early decades of the 19th century had been modest at best, ranging only from between 200 to 2,000 persons per year. Indeed, most German Americans living in the U.S. in 1830 had arrived before the American Revolution and were fully assimilated into U.S. society. Only after 1830 would German immigration substantially increase. In 1832, for instance, roughly 10,000 German immigrants arrived, and in 1837, there were almost 25,000. These were still relatively small numbers, though, compared with the number of arrivals that came after 1850. For instance, “from 1852 to 1854 more than half a million Germans came to America,” pushed by political unrest in Germany as well as by the “rise of the factory system which threw tens of thousands of artisans out of work.”[34]

8. The Spirit of 1848

1 As new German immigrants entered the U.S. in record numbers through the ports of New York and Baltimore in the mid to late 19th century, they flowed into the region around the Great Lakes and along the Ohio River. A smaller but significant number entered in New Orleans and streamed up the Mississippi River to its confluence with the Missouri River just north of St. Louis. By the time the American Civil War broke out (1861–1865), the German population was heavily concentrated in a 200-mile-wide belt stretching across the northern states from New York and Maryland to the Mississippi. Cities like Cincinnati, Detroit, Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Louis had all acquired strong German elements.[35]

2 The quickening of German immigration after 1830, and even more so after 1848, was prompted in part by a desire to be rid of the old, hereditary, monarchical systems of privilege characteristic of life in much of Europe. In 1848, widespread demands for democratic reforms in Germany and elsewhere featured impassioned crowds taking to the streets, engaging in protests and sometimes armed confrontations to challenge the established order.[36] When the revolution failed, many revolutionists had to run for their lives from the aristocracies they had tried to overthrow. Many of them fled to the United States. Although those who had taken an active role in the revolution were but a small minority of the nearly one million Germans who came here in the 1850s, the revolutionists’ idealism was widely shared by the majority of their fellow countrymen.[37]

3 The Forty-Eighters, as they would come to be called, were quite diverse in their political views, regional backgrounds, and occupations, but they tended to be united in their dedication to principles of freedom and democracy, and most were fiercely anti-slavery.[38] Forty-Eighters were also strongly inclined towards active participation in politics, unlike the majority of German immigrants—both those who had come before 1848 and those who would come after—who tended to be disinterested in politics.[39] Consequently, Forty-Eighters wound up playing a major role in the politics of the immediate pre– and post–Civil War eras.

4 Another notable characteristic of the Forty-Eighters was their tendency to reject conventional religious belief. Whereas most German Americans were religiously devout, “[t]he typical Forty-Eighter was a freethinker, if not an atheist.”[40] A freethinker in this context was someone who took the philosophical position that “beliefs should not be formed on the basis of authority, tradition, revelation, or dogma,” but “should instead be reached by other methods such as logic, reason, and empirical observation.”[41]

* * *

5 The Forty-Eighters arrived in the United States at a time when two major political issues were roiling the country. First, there was the problem of slavery which had become ever more contentious with the westward expansion of the country. While an uneasy equilibrium had existed between the original northern and southern states with respect to their positions on slavery, the question of whether slavery would be permitted in the new western territories was becoming so divisive in the 1850s that it would only be settled by a civil war.

6 In 1820, Congress had passed a law known as the Missouri Compromise, which sought to balance the desires of northern states to stop the expansion of slavery, with the desires of southern states to expand slavery. The compromise allowed Missouri to become a new state where slavery would be permitted, while Maine would become a new free state. The compromise further stipulated that in the future, slavery would not be permitted in the western territories north of 36°30′ N latitude—or roughly the line running due west along a line described by Missouri’s southern border. This would have excluded slavery from the Kansas and Nebraska territories when they were conceived decades later.

7 Unfortunately for abolitionists, in 1854, the Missouri Compromise was undermined by the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which granted to the settlers themselves the right to decide the question of slavery in those territories. Violent clashes followed the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act as pro-slavery settlers flooded into Kansas seeking to establish slavery in violation of the agreement that had been established by the Missouri Compromise. These circumstances laid the foundation for the birth of the modern Republican Party (as distinct from the earlier Jeffersonian Republican Party, which had been largely absorbed by a Democratic Party that was becoming ever more wedded to the preservation of slavery). Indeed, the new Republican Party came together primarily in opposition to the expansion of slavery into the western territories, with many Republicans arguing for the eventual abolition of slavery.

8 Because they were consistent in their dedication to principles of liberty and democracy, Forty-Eighters tended to be adamantly opposed to slavery, which they believed made a mockery of the Declaration of Independence.[42] Many Forty-Eighters were, therefore, naturally attracted to the new Republican Party.[43]

9 The second major political issue of the day that naturally concerned Forty-Eighters was the status of immigrants in the eyes of native-born Americans, especially those of English descent, many of whom were quite likely to define a “true” American as someone that was at least culturally English, if not of English descent. This tended to complicate the political allegiances of Germans, whether they belonged to long-settled German American communities, or whether they were more recent arrivals, like the Forty-Eighters.

10 Traditionally, German Americans had been Democrats, for the Democratic Party had historically been the immigrant-friendly party, depicting itself as “the natural home of the foreign-born and the national guarantor of their aspirations for liberty, democracy, and opportunity”[44]—even if it explicitly promised these blessings only to White people.[45] The Democrats were usually quick to remind immigrants of the party’s historically staunch resistance to “every attempt to abridge the privilege of becoming citizens and the owners of soil,”—a reference to its opposition to the Alien and Sedition Acts during the Federalist era.[46]

11 Democrats also presented themselves as the defender of workers’ rights. Indeed, the Democrats had significant support in the industrialized, urban North where many Irish and German immigrants, including Germany’s many craftworkers, earned their livings. Generally speaking, “German-American Democratic leadership included large numbers of earlier immigrants,” especially businessmen, manufacturers, newspaper publishers, or conservative ministers—”who were more firmly tied to the economic, political, and ideological status quo than most newcomers.”[47]

12 In contrast to long-established, conservative-leaning German Americans—sometimes called “Grays,”—the Forty-Eighters (or “Greens”) were generally more liberal, if not radical. Although both groups opposed slavery, the Greens were generally more vocal in their opposition, while the Grays were more inclined to put the issue out of mind. These differing political inclinations might help partly explain why Forty-Eighters were quick to support the new, anti-slavery Republican Party when it arose in 1854 during the Kansas-Nebraska furor, while older Germans remained loyal to the Democratic Party despite its pro-slavery platform.[48]

13 But it must have been a tricky balancing act for many German Americans to sort out their political allegiances after the rise of the Republican Party, for while Republicans stood decidedly against slavery, the party also harbored some nativist factions that were hostile to immigrants. The rise of anti-immigrant prejudice corresponded, as it always does, with the dramatic increase in immigration that began in the 1850s. The paranoia that seized certain Anglo-Americans soon manifested itself in the movement that became know as the Know-Nothing movement, so called because its members, when asked questions about the movement, pretended to “know nothing” about it.[49]

14 So the Democratic Party was pro-immigrant but also pro-slavery, and the Republican Party was anti-slavery, but with anti-immigrant factions as well. An anti-slavery immigrant had little choice but to struggle “to evaluate political issues and prioritize them according to their importance.” At any rate, according to Bruce Levine, the available data on voting patterns suggest that “overall, support for the Republican party grew significantly among German working people between 1856 and 1860”[50] despite the fact that the growing Know-Nothing movement might have made some German Americans think twice about supporting Republicans.

15 By 1855, Know-Nothings had acquired significant power in seven states, winning governorships and seats in state legislatures, and even gaining seats in the U.S. Congress. Know-Nothing supporters attacked German American churches, halls, festivities, and picnics, precipitating bloody riots in cities around the country, including in Columbus, Cincinnati, and Louisville. Things got so bad that German Americans felt compelled to form self-defense militias, and violent clashes with Know-Nothing mobs sometimes occurred.[51] In the end, the approaching national crisis leading up to the outbreak of Civil War along with “the increasing political clout of German-Americans eventually led to the downfall of the Know-Nothings, as German-Americans came to be viewed as essential to victory in the election of 1860.”[52]

9. The Most Famous Forty-Eighter

1 Without a doubt, the most renowned representative of the spirit of 1848, and especially of the essence of the German contribution to that movement, was Carl Schurz. He embodied “its idealism and its ideals, its vigor and independence, its youthful buoyancy and optimism.” Born Karl Schurz on March 2, 1829, in the village of Liblar near Bonn on the Rhine, Schurz was just 19 years old on the eve of the 1848 revolution. Deeply committed to hopes of German unification and a democratization of the government, Schurz had been forced to flee when the revolution failed, going first to Switzerland and then to London. In London, Schurz married Margarethe Meyer of Hamburg, and a month later in August 1852, the young couple immigrated to the United States.[53]

2 Schurz’s rise to fame, influence, and respect in America was astounding. It began quietly enough for a newlywed, twenty-three-year-old immigrant landing in New York, with virtually no fluency in English at all. In Schurz’s own words:

Here in America I lived for several years quietly and unobtrusively in an ideal happy family circle. … I studied, observed, and learned assiduously, until at last in the year ’56, when the movement against slavery developed magnificently, I found myself drawn into public life. I knew that I should accomplish something. America is the country for ambitious capability, and the foreigner who studies its conditions thoroughly, and with full appreciation, can procure for himself an even greater field of activity than the native.[54]

3 During these first few “quiet years,” Schurz dedicated himself to learning English as quickly as he could, adopting a method that we might today call the “reading method.” It began with the daily reading of a newspaper. Soon he supplemented this by reading “the works of Goldsmith, Scott, Dickens, Thackeray, Macaulay, the commentaries of Blackstone (as he was looking forward to a legal career), and last of all, because of their enormous vocabulary, the plays of Shakespeare.” After a time, he supplemented this reading with exercises in translation.[55]

4 To Schurz, the greatest impulse to human action was the unselfish pursuit of a spiritual objective, and this he found in the pursuit of the abolition of slavery, a cause that would eventually bring him into the orbit of future president Abraham Lincoln. Schurz developed immense admiration and respect for Lincoln at the same time that he developed a deep abhorrence of Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas, Lincoln’s chief rival, whom Schurz regarded as an avowed defender of the slave system. As Schurz became involved in politics, he initially honed his public speaking skills on German-speaking audiences, learning first how to capture a crowd in his own language before eventually attempting to do it in his adopted language. When the time came, Schurz campaigned for Lincoln in front of German-speaking and English-speaking audiences alike, taking Douglas apart with power and wit. Schurz has often been regarded as instrumental “in helping to bring about the election of Lincoln in 1860.”[Morgan, 230–231.[/footnote]

5 After Lincoln became president, he appointed Schurz to serve as ambassador to Spain, but when the Civil War broke out, Schurz received a commission to serve as a Union Army general, participating ably as a commander in many well-known battles, including the Second Battle of Bull Run, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, and the Battle of Chattanooga. When the war ended, Schurz resigned from the army. Three years later, he ran to represent the state of Missouri in the U.S. Senate, becoming the first German American to serve in that body, where he dedicated himself to reforming the civil service.[56]

6 In 1876, Schurz was appointed by President Rutherford B. Hayes to be Secretary of the Interior, the Department that, among other things, oversaw Indian affairs. Unfortunately, despite his sympathy for the injustices faced by Native people, Schurz’s tenure as Secretary of the Interior might be seen in retrospect as having been marred by his support for the assimilationist policies of the day. In particular, his backing of initiatives like industrial schools, which sought to assimilate Native American children into mainstream culture, can be criticized for contributing to the erosion of indigenous self-determination and cultural heritage.[57] However, at a time when no one was able to exercise sound judgement on a just path forward in Indian affairs, perhaps it is too much to ask for perfect insight from a man whose moral instincts were otherwise so often correct.

10. German Americans and the Civil War

1 When the Civil War broke out in 1861, German Americans and especially Forty-Eighters—as exemplified by Carl Schurz as just discussed above—overwhelmingly sided with the North. There were many reasons for this, and the average German American may have had his or her own reasons, but three possibilities are worth noting here.

2 First, because of the German commitment to liberty and equality, Germans could not identify with the Southern cause, i.e., the preservation of “a system that depended on slavery for its livelihood.” Closely associated with this was the fact that the landed aristocracy of the South reminded German immigrants of the European nobility system that they had left Germany to be free from. Secondly, “[m]ost Southern plantation owners were opposed to European immigration” since their economic system did not require it.[58] The economic system of the North, by contrast, was aligned with the economic interests of immigrants. Thirdly, German Americans opposed the idea of secession. If some of the old-time German farmers were apathetic and failed to see why it should concern them, Forty-Eighters were quick to educate them. Using their old homeland as “glaring proof of the dangers of disunion,” Forty-Eighters pointed out the folly of allowing the only “outstanding republic in the world, whatever its faults” to disintegrate into disunion. German Americans, they argued, had “an obligation to prevent that calamity in their adopted country.”[59]

3 So when President Lincoln called for volunteers to serve in the Union Army, German Americans were quick to respond. For example, within two days, German Americans in Cincinnati met in the Turner Hall to form Ohio’s all-German Ninth Infantry Regiment. Over the next several days, enough men had volunteered to form the regiment’s requisite ten companies. “Similar scenes occurred in Chicago, Milwaukee, Indianapolis, Philadelphia, and New York.”[60] Overall, German Americans enlisted in numbers that far exceeded their percentage of the total population. Although people of German ancestry made up less than 5% of the free White population of the United States in 1860, they made up 30% of the Union Army.[61] Of the 2.5 million soldiers in the Union Army, for instance, 750,000 were German American or German-born immigrants. In fact, “the German-born alone amounted to 216,000,” and the Union Army had about 500 German-born officers.[62]

4 However, none of this should be taken to mean that all German Americans approved of the war. Party affiliation—whether or not the German American community of any particular state or locality had voted Democratic in the 1860 election or whether they had swung over to the newly founded Republican Party—predicted in large part the degree of community support for the Union cause. For instance, Germans in “Missouri, Illinois, Minnesota, and the cities of Brooklyn, Buffalo, and perhaps Pittsburgh,” where Republicans had prevailed, were more supportive of the Union cause. But in the states of “Wisconsin, Iowa, Indiana, and in New York City, Albany, and Philadelphia,” where Democrats had retained the majority, people were less enthusiastic. Indeed, in Wisconsin in 1862, it became “necessary to impose a draft to meet the state’s troop obligations,” which prompted a local revolt in which “a drunken mob … seized and destroyed the draft lists and drove off the officials in charge.”[63]

5 Although the overwhelming majority of Germans who served in the military during the Civil War did so for the Union, there were German Americans that fought for the Confederacy. But compared to the northern German Belt where the vast majority of Germans had settled, the German population in the South was considerably more sparse, and the presence of German Americans in the Confederate Army was therefore correspondingly much smaller. At the time of the Civil War, only about 75,000 Germans lived in southern states, including 15,000 in New Orleans, and not all of them supported the Southern cause, even if there were some that did.[64] In fact, “[w]hen the war began, many Germans fled North.” Nevertheless, Texas, Virginia, and Louisiana had enough of a German presence to field a number of all-German companies, as did Georgia.[65]

6 In the end, whether by conviction or by coincidence, the majority of German Americans could boast that they had fought on the right side in the defining issue of the day—the slavery issue. As Rippley has put it:

For many years after the war, editors of German-language newspapers could proudly place their ethnic brothers behind the cause of equality, justice, and reform, customarily asserting that the Germans were solidly aligned with Lincoln’s principles. Identified with the Great Emancipator, they could forever see themselves as having formed a bulwark against the immorality of slavery, against the illegality of secession, and not least, against the xenophobia of Know-Nothingism.[66]

7 In the meantime, although the influx might ebb and flow in any given year due to the ups and downs of the economy, Germans continued to immigrate in robust numbers until the end of the century, lured by the Homestead Act of 1862 that granted free land to anyone who staked a claim and lived on it for at least five years, and by the post-Civil War industrial expansion that produced a desperate need for immigrant labor. From 1820 to 1900, 5 million Germans came to America, more than any other group. Their closest rivals were the Irish (3.8 million) and the Brits (3 million).[67]

11. The Anglo/German Cultural Divide

1 By the beginning of the 20th century, German communities comprised the largest (or second largest) immigrant group in many cities across the Northeast and Midwest, including Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, Buffalo, Cincinnati, Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Louis, among others. Moreover, German immigrants had introduced many things that seem to us today typically American, for example, new foods and beverages such as hot dogs, pretzels, lager beer, etc.; educational methods and systems like kindergarten, high school, the research university, physical education, and vocational education; holiday traditions including the Christmas tree, Santa Claus, the Easter Bunny and Easter egg hunts.[68] Anglo Americans had come to see many of these things as parts of American culture.

2 However, fundamental ideological differences prevented Anglo Americans and German Americans from seeing eye to eye on many issues that went straight to the heart of what it meant to be an American, or indeed to become an American. Anglos “had confidence in the ability of American institutions and culture to incorporate diverse European groups into one national culture and society dominated by a white, English-speaking Protestant majority.” Germans, on the other hand, already politically and economically integrated, did not especially appreciate the notion that immigrants (or their offspring) should be expected to defer in matters of culture to an English-speaking Anglo elite.[69]

3 Instead, German Americans “argued for a pluralistic understanding of American society in which the preservation of the ethnic group and its language, culture, and institutional structure was understood as a societal benefit that should be promoted and defended.” To these German Americans, being a true American was a matter of “exemplify[ing] American ideals, especially the idea of liberty,” and “[t]he best way of expressing one’s freedom as an American was to be true to one’s ethnic heritage.” In other words, for German Americans, “being a good American meant being a good German: speaking good German, being active in German social and cultural groups, and displaying the positive characteristics of German immigrants … to other groups.” Believing that “they could pick and choose which aspects of American culture they wished to adopt,” German Americans saw no contradiction in their desire to live in their own neighborhoods, maintain their language, and not marry outside of their group while still being fully American. “In short, German Americans believed that they could assimilate into American society on their own terms, not the terms of the larger, Anglo American English-speaking Protestant majority.”[70]

4 Indeed, German Americans found much in the typical Anglo American attitude and lifestyle that they positively disliked. For one thing, they did not approve of the egalitarian relationships they observed in the Anglo family, especially as reflected in the relationships between children and parents. The German family, with the father as the undisputed head of the household, was clearly more patriarchal. In the world of work and business, German Americans disliked the Anglo penchant for speculative and risky investment, and sometimes even shady business dealing, with the aim of obtaining individual financial wealth. To the German American, the purpose of work was to provide for the support of the family, and the value of work was in its quality, not the salary attached to it. But even more significantly, perhaps, because it directly threatened the German American life style, Germans criticized the tendency of Anglo women to be continually involved in crusades designed to reform society according to Anglo values.[71]

5 More concretely, Germans opposed what they saw as Puritan-inspired efforts on the part of zealous Anglo Americans to pass laws against alcohol consumption and Sabbath-breaking. For German Americans, the frequenting of Lokals and beer gardens was a cornerstone of social life in the late 19th and early 20th century. And the designation of Sunday as a day for the whole family to get together with friends to enjoy beer or wine and perhaps a picnic basket at a local park or neighborhood beer garden was another aspect of it.[72] If Anglo Americans wanted to abstain from alcohol and set Sundays aside for Bible reading, that was certainly their right. But why should they impose it on others?

* * *

6 To best appreciate German American social life between the Civil War and World War I, a brief profile of Kleindeutschland, the large German quarter of New York City, may be useful. In 1880, German immigrants and their American-born children made up an astounding 549,142 people, or nearly half of New York’s population of 1.2 million, making it the third-largest German-speaking city in the world behind Berlin and Vienna.[73] As Ziegler-McPherson has elaborated:

In Kleindeutschland, a German immigrant could buy German food and other household items at thousands of German grocery stores, delicatessens, butcher shops, and bakeries; drink German-style lager beer in more than five hundred Lokals (bars); drink beer and listen and dance to German music at eight hundred beer gardens; see a classical German play or new vaudeville skit at three theaters; read more than twenty German-language newspapers and magazines; buy German-language books at Westermann and Company or Ernst Steiger’s or borrow them from the Astor Library; participate in thousands of clubs, fraternal orders, and labor unions; exercise and play sports at two gymnasiums; bank at the Germania Bank, Sender Jarmulowsky’s bank, the German Savings Bank, the German American Bank, or the German Exchange Bank; receive unemployment, injury, or funeral assistance from thousands of mutual benefit societies; and on Sunday, choose from thirty-three churches and synagogues that conducted services in German. Only the public schools in the neighborhood were controlled by outsiders, and even here, some New York City public schools offered instruction in German. Parents could also choose from eleven private German-language schools for their children.[74]

7 Moreover, the German community was highly organized, and just as in Germany the Verein (plural, Vereine) played a central role in community social life. Vereine were clubs, associations, or societies, of which there were many different sorts: mutual benefit and charitable societies, homeland societies, and labor unions; choirs, bands, dance clubs, and theater clubs; sports clubs devoted to fencing, gymnastics, and shooting; religious societies, and the list goes on. Indeed, there were thousands of such Vereine in New York, and it was not unusual for a person to belong to more than one.[75]

8 As previously mentioned, the prominent role of social drinking and the German notion of how best to spend a Sunday afternoon were particular sources of cultural contention between German and Anglo Americans. In 1880, the typical New Yorker worked a six-day week. German immigrants attended their Vereine (meetings) in the evenings and on Sundays. The meetings were accompanied by social drinking and attended by men, women, and children alike, which was shocking to Anglo Americans (not to mention illegal in New York). In fact, the German and the Anglo conception of the bar or saloon were worlds apart. The traditional Anglo bar, for instance, was exclusively a man’s domain, and the only women that might be tolerated were prostitutes. But for German Americans, bars and beer gardens were family-friendly environments, and visiting the local beer garden was a common way for the family to spend a Sunday afternoon or evening.[76]

12. The Great Disappearing Act

1 The outbreak of World War I was a tragedy, not just for the countries involved, but also for the status of Germans in America. As Ziegler-McPherson has suggested, “Before World War I, German Americans had been the ethnic group best positioned to promote alternative visions of American society and theories of assimilation, and the United States had countless large and small German communities where this alternative understanding of pluralism was developed and lived on a daily basis.”[77] Yet the end of the war in 1918, “nearly all visible aspects of German culture in New York City had been eliminated,” and by 1930, “the institutions and social activities that had made the German community so visible for so many decades were largely gone.”[78]

2 World War I began as a quarrel between Austria and Serbia when a Bosnian-Serb nationalist assassinated the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and his wife Sophie, Duchess von Hohenberg. In the beginning, Americans of all backgrounds hoped the incident would remain a local affair. But unfortunately, the European powers had aligned themselves in mutual defense agreements which pitted Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy against France, Russia, and the United Kingdom. When Austria held Serbia responsible for the assassination and declared war on Serbia, Russia came to Serbia’a defense, which prompted Austria’s ally, Germany, to declare on Russia, drawing France and the United Kingdom into the conflict against Germany and Austria; soon all of Europe was at war.

3 At first, German Americans, and indeed Americans of all backgrounds, tended to oppose U. S. intervention and urged the United States to remain neutral. “The loudest voices for neutrality were German-language newspapers, who sought to both inform their readers of the German side of the war and to lobby for neutrality,”[79] while “the English-language press increasingly supported England.” Publicly, President Woodrow Wilson had consistently called for American neutrality, although his actions made it clear that “he was not only pro-English, but anti-German.” In fact, the whole Wilson administration was dominated by Anglo Americans who were clearly pro-British.[80]

4 Meanwhile, the U.S. remained neutral for thirty-three months from August, 1914 until April, 1917. During that time, however, German Americans faced increasing hostility, especially from Anglo Americans who increasingly sought to assert the idea of “100 percent Americanism” as the primary way of defining one’s Americanness. According to this position, one could only be 100 percent American, and nothing less. The idea of being a “hyphen,” for example, German-American or Irish-American, was unacceptable.[81]

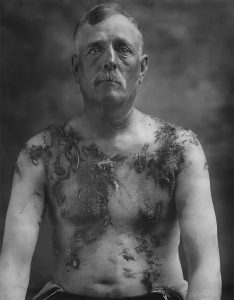

5 After the U. S. entered World War I, an anti-German hysteria took hold of the country. People of German heritage and all things German became its target. German Americans’ loyalty to the United States was questioned. More than six thousand Germans who were legal residents, but not yet naturalized citizens, were rounded up and interned at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia, as “enemy aliens.” German language use came under attack in whatever form it took. Twenty-six states passed laws against the use of German anywhere in public. The German American press was censored. The Secret Service often raided the offices of its editors. The post office sometimes refused to deliver German-language publications to subscribers. German language instruction was eliminated from schools, and German language materials were removed from libraries. German American associations and community leaders came under attack amid efforts to shut the organizations down. Individuals of German descent were harassed, threatened, beaten, and lynched. Germans were slandered in the mass media and depicted in hateful and offensive ways in cinema. And even after the war ended, anti-Germanism continued for some time unabated.[82]

6 German Americans responded to these unrelenting attacks by performing what Ziegler-McPherson has described as a “Great Disappearing Act.”

Yes, German Americans continued to meet with friends and socialize, but these gatherings were more often informal than formal, and groups no longer chose to identify themselves as German to their neighbors and the larger community … There was no more parading around the street on the way to or from a Verein celebration; the picnics and festivals that had attracted thousands were over.[83]

German Americans had simply become one among the many ethnic groups in the city with no special prominence.

13. Weathering World War II

1 When the Second World War broke out, German Americans rightly worried about the possibility of once again becoming victims of anti-German hysteria. But while the war did engender renewed anti-German sentiment, its severity compared to that which had accompanied the First World War was mitigated by a number of factors.

2 First, the visibility of German Americans as a distinctive ethnic group had been greatly reduced following their “great disappearing act” after World War I. Therefore, there were fewer targets to excite anti-German hysteria. Secondly, while German Americans had spoken out in defense of Germany during the First World War, they either maintained a firmly isolationist or neutral position, or were openly critical of Hitler’s Germany during the Second World War. Moreover, President Franklin Roosevelt was more careful not to speak out against the German American community as Woodrow Wilson had done twenty years earlier, therefore not encouraging anti-German sentiment. (However, nearly 11,000 German Americans did find themselves interned upon suspicion of “potential for espionage or sabotage.”[84] although this paled in comparison to the more than 100,000 Japanese Americans that were interned based on no reason other than race.)[85]

* * *

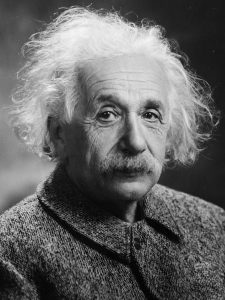

3 In the immediate aftermath of the Nazi takeover of Germany, more than a million Germans fled to escape tyranny and persecution. Two hundred thousand of them came to the U.S., among them “scientists, artists, musicians, writers, philosophers, doctors, architects, and actors, many of whom were Jewish.” No doubt the most famous was Albert Einstein[86]

4 From 1941 to 1950, a quarter of a million more German-speaking immigrants came to the U.S., displaced from eastern and southeastern Europe, the Soviet Union, and the old eastern German provinces of Pomerania, Silesia, and East Prussia. In the 1950s and 1960s, as Germany rebuilt, another three-quarter of a million came. Only in the 1970s did the numbers drop to less than one hundred thousand. And although German Americans had adapted to the anti-German prejudice of the two world wars by laying low and staying out of sight, the newcomers started something of an ethnic revival. Thanks in part to the success of the post-war German recovery and the remarkable turnaround in U.S.-German relations, anti-German sentiment seemed to have been reversed. It also did not hurt that Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in Europe, and President of the United States from 1952 to 1960, was of German descent.[87]

14. Return of Ethnic Pride

1 By the 1970s, the United States was becoming more tolerant of celebrations of ethnic pride, at least when it came to ethnic groups that were considered White. People of color would still have to fight for a place in the sun, as other chapters in this book illustrate, although by this time there seemed to be an awakening among some segments of the population of the need to right historic wrongs towards America’s “despised” minorities. At any rate, a number of reasons for the 1970s “ethnic heritage revival” can be mentioned. First, there was the posthumous re-publication in 1964 of President John F. Kennedy’s 1958 book A Nation of Immigrants. Kennedy, the first Irish American president, had celebrated America’s pluralistic ethnic heritage, and German Americans appreciated his praise of their contributions to U.S. culture.[88]

2 The passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 also represented a significant break with nativist immigration policies that had been in place since the 1920s, when the number of immigrants in the U.S. reached its peak. In 1921, the U.S. had imposed tight controls on new immigration through a mechanism known as the National Origins Formula, which laid the foundation for the Immigration Act of 1924. This law was designed to preserve American homogeneity by favoring immigration from Western and Northern Europe while limiting immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe and Asia.[89]

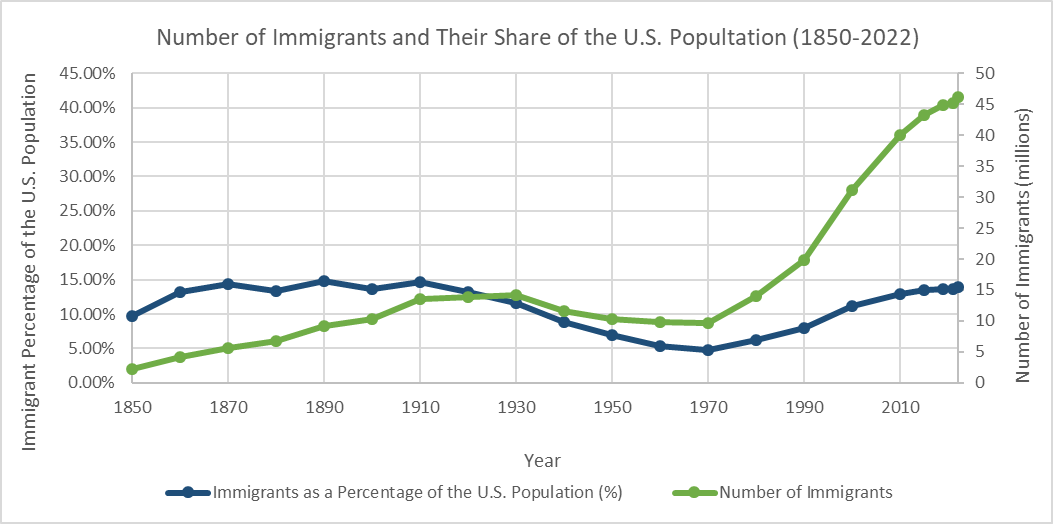

3 As a result of the Immigration Act of 1924, the number of all immigrants as a percentage of the total U.S. population fell from 13.2% in 1920 to 4.7% in 1970. The clearly discriminatory U.S. immigration policies were increasingly being criticized by international organizations such as the United Nations and by the Civil Rights Movement in the U.S. By contrast, the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act led to a dramatic increase in immigration, as demonstrated in the graph below, and it opened the possibility of immigration to many previously excluded groups.

4 Education policy in the U.S. throughout the 1960s and ’70s also did much to promote an interest in ethnicity and pluralism through laws such as the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (1965) and the Ethnic Heritage Studies Act (1972). Then in 1976, the United States celebrated its Bicentennial, i.e., its 200th birthday as a nation, during which many conferences, publications, and celebrations highlighted the contributions of Germans from the American Revolution on. When it came time for the 1980 census, the U.S. Census Bureau included questions to gather more detailed information about people’s ethnic backgrounds. These data demonstrated that people of German ancestry made up a larger share of the U.S. population than many had previously realized. In fact, when considering various German heritage groups such as Austrians, Swiss-Germans, Alsatians, and Luxembourgers, it became apparent that people of German ancestry constituted one of the largest ethnic groups in the U.S.[90]

5 It seemed that for the first time since before the world wars, German Americans could once again feel free to take pride in their heritage. German heritage festivals enjoyed a revival, in particular Oktoberfest. Cities with an historically large German presence, like Cincinnati and Milwaukee, reintroduced German bilingual programs. German American institutes and centers sprang up in universities across the country, and German historical and heritage societies were established in many historically German localities.[91]

15. German American Identity Today

1 Despite the openness to celebrations of ethnic identity brought about by the ethnic heritage revivals of the ’60s and ’70’s and the multicultural movement of the ’80s and ’90s, most Americans of German descent no longer identify strongly as German American. Most are clearly aware of their German family background and remain perfectly willing to report it in ancestry surveys. They may even casually embrace certain German cultural elements, such as attending a local Oktoberfest or enjoying German cuisine, but this in itself doesn’t make them much different from Americans with no German heritage at all who may do the same thing.

2 At the same time, data from the 2020 United States Census indicate that “German” (either alone or in combination with other ancestries) is the most frequently reported ancestry in the United States today. People of German ancestry comprise about 12.8% of the U.S. population, a proportion which is greater than any other ethnic group. “English” and “Irish,” in nearly equal proportions (about 9.5%), are the second and third most frequently reported ancestries.[92]

3 It might seem surprising that people of German descent outnumber those of English descent, but it is important to keep in mind that census data is based on self-reporting, and individuals may choose how they wish to identify their ancestry or ethnicity. It is therefore possible that people of German descent only appear to outnumber people of English descent because the latter do not specifically identify as English; rather they may simply identify as “American,” which is the fourth most frequently reported ethnicity (5.3%). But it is also possible that some people of German descent do not identify as such and identify as “American” as well. Either way people of German ancestry make up a significant proportion of America’s multi-ethnic society, clearly vying with Anglo Americans for the status as the largest ethnic group in the U.S.

4 And although individuals of German ancestry tend not to openly proclaim their German heritage as their ancestors once did, communities in the Midwest, like Cincinnati or Milwaukee, where 19th century German settlement was most concentrated, still seem willing to display their German ethnic roots. On the other hand, signs of German ethnicity are barely noticeable in the Mid-Atlantic, where most 18th century German settlement occurred and which in the 19th century was “a close second to the Midwest as a destination for … German newcomers.”[93]

Chapter 5 Study Guide/Discussion Questions

Activity 5.1

After reading subsections 1–5 of the chapter, answer and discuss the following questions with one or more fellow readers.

- What evidence can you find to support the argument that perhaps the Germans deserve to be regarded as among the principal founders the United States?

- What evidence can you find to support the generalization that the earliest German arrivals in the American colonies were not culturally homogeneous?

- Describe the friction that existed between the English and the Germans during the colonial era. Describe some of the prejudicial and stereotypical views that English colonists held towards the Germans.

- Describe some German contributions to the American Revolution.

- What role did Germans play in the founding the new Republic?

Activity 5.2

Based on subsections 6–9 of the chapter (and keeping in mind that all German Americans did not agree with each other on every political matter) what political positions might be most typical of German Americans in the period between the American Revolution and the Civil War?

- Create a table like the one below to summarize your conclusions.

| Topic | Typical German American Position |

| Opposition to the Federalists | |

| Support for the Democratic-Republicans | |

| Opposition to the Know-Nothings | |

| Opposition to the Southern Democrats | |

| Support for the Modern Republicans |

2. Given German American pro-immigration and anti-slavery positions, what dilemma did the Modern Republican Party pose for German Americans?

3. What two major rationale did German Americans give, especially Forty-Eighters for supporting the North during the American Civil War?

Activity 5.3

Based on subsections 10–12 of the chapter, answer and discuss the following questions with one or more fellow readers.

- Identify typical areas of cultural conflict between Anglo Americans and German Americans during the late 1800s and early 1900s.

- How did World War I create a problem for German Americans? In your opinion, did German Americans have a point in urging American neutrality in World War I? To what does the phrase “the Great Disappearing Act” refer?

- How was the typical German American response to World War II different from their response to World War I? What factors may have moderated American suspicion of German Americans somewhat during World War II as compared with World War I? In what sense was U.S. involvement in World War II perhaps more justifiable than its involvement in World War I?

Activity 5.4

- Identify at least two factors at play during the 1960s and ’70s that may have contributed to a renewed sense of pride among German Americans?

- What changes occurred in the framing of the 1980 U.S. Census, and what big surprise did the survey reveal?

- In what regions of the country does German American heritage seem to be most fully on display?

- As we will learn in the next chapter, people of Irish American ancestry often proudly embrace an Irish identity. Based on what you have learned about the history German people in America, what is your theory about why people of German ancestry in the United States are not similarly attached to a German identity?

Media Attributions

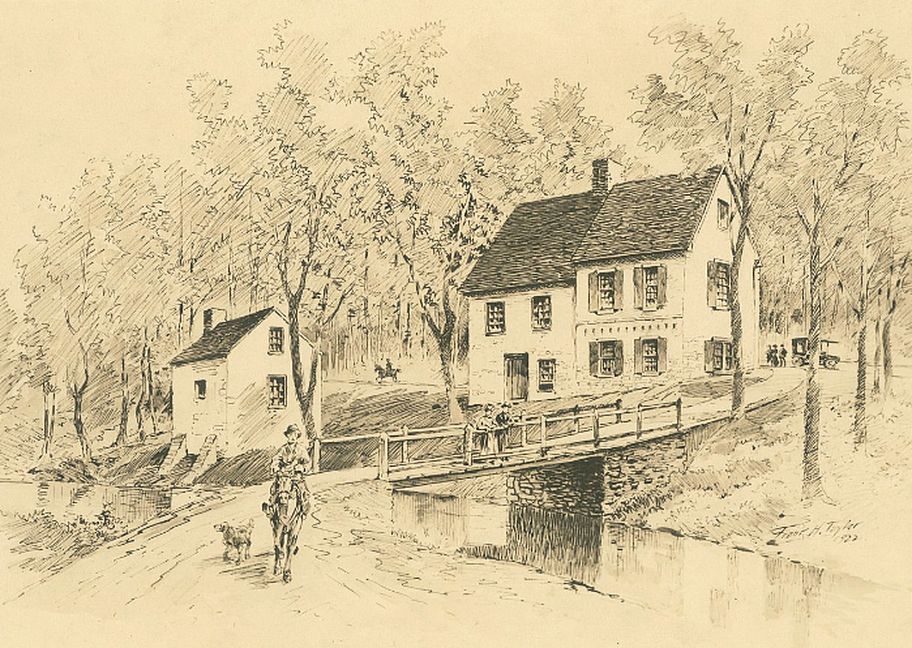

- Gallery Images – Historical Houses in Germantown, Pennsylvania

- Bechtel House © Smallbones is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Theoboldt Endt House © Smallbones is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Clarkson Watson House © Smallbones is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Grumblethorpe Tennant House © Smallbones is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Ottinger House © Smallbones is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Howell House © Smallbones is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Rittenhouse Manor © Frank Hamilton Taylor is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Farm with a Pennsylvania German–style barn © Nicholas A. Tonelli is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Peter Muehlenberg © Author Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

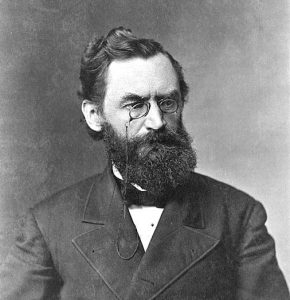

- David Rittenhouse © Charles Willson Peale is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Michael Hillegas © Bureau of Engraving and Printing & Smithsonian Institution is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Frederick Augustus Conrad Muhlenberg © Joseph Wright is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Missouri Compromise © User:Golbez. is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Carl Schurz © M.B. Brady is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 20th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment German Officer Corps © Unknown/James Steakley is licensed under a Public Domain license

- German Beer Garden © Alfred Fredericks is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license. Used with permission under Fair Use

- John Meintz, Tarred and Feathered © Author Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Dormitory of Interned Germans © Bain News Service is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Albert Einstein © Orren Jack Turner is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Immigrants 1850-2022 © Migration Policy Institute. Adapted here for non-commercial educational purposes under fair use. The graph is not covered by this book’s Creative Commons license.

- Percentage of Americans with German Ancestry © Abbasi786786 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Don Heinrich Tolzmann, The German-American Experience, (Amherst, NY: Humanity Books, 2000), 31–35. ↵

- Walter D. Kamphoefner, Germans in America: A Concise History, (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2021), 9. ↵

- Tolzmann, The German-American Experience, 36–42. ↵

- Kamphoefner, Germans in America, 9–10. ↵

- Tolzmann, 45. ↵

- Kamphoefner, 11. ↵

- Kamphoefner, 11. ↵

- Kamphoefner, 11–12. ↵

- Wikipedia contributors, "Great Frost of 1709," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed June 21, 2023). ↵

- Kamphoefner, 12. ↵

- Wikipedia contributors, "German Americans: Palatines," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed June 21, 2023). ↵

- Wikipedia contributors, "German Americans: Colonial Era," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed June 21, 2023). ↵

- Kamphoefner, 12–13. ↵

- Tolzmann, 89–90. ↵

- Tolzmann, 90. ↵

- Tolzmann, 85. ↵

- Tolzmann, 85–86. ↵

- Tolzmann, 85–86. ↵

- Tolzmann, 88; 95–96. ↵

- Tolzmann, 97–98. ↵

- Tolzmann, 101–102. ↵

- Tolzmann, 111–112. ↵

- Tolzmann, 111–112. ↵

- Tolzmann, 113. ↵

- Wikipedia contributors, "David Rittenhouse," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed June 23, 2023). ↵

- Tolzmann, 113. ↵

- Tolzmann, 113–114. ↵

- Wikipedia contributors, "First Party System," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed July 9, 2023). ↵

- Tolzmann, 114. ↵

- Tolzmann, 115. ↵

- Kamphoefner, 25. ↵

- John Van Houten Dippel, Eighteen Hundred and Froze to Death: The Impact of America's First Climate Crisis, (New York: Algora Publishing, 2015), 2–3. ↵

- Kamphoefner, 25. ↵

- Tolzmann, 122; 151. ↵

- La Vern J. Rippley, The German-Americans, (Lantham, MD: University Press of America, 1976/1984), 44. ↵

- Carl J. Friedrich, “The European Background.” In The Forty-Eighters: Political Refugees of the German Revolution of 1848, edited by A. E. Zucker, (New York: Russell & Russell, 1950/1967), 4–7. ↵

- Mischa Honeck, We Are the Revolutionists: German-Speaking Immigrants and American Abolitionists After 1848, (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2011), 2–3. ↵

- Honeck, We Are the Revolutionists, 3. ↵

- Friedrich, “The European Background,” 22; Lawrence S. Thompson and Frank X. Braun, "The Forty-Eighters in Politics." In The Forty-Eighters: Political Refugees of the German Revolution of 1848, edited by A. E. Zucker, (New York: Russell & Russell, 1950/1967), 111–112. ↵

- Friedrich, “European Background,” 20–21. ↵

- Wikipedia contributors, "Freethought," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed July 6, 2023). ↵

- Bruce Levine, The Spirit of 1848: German Immigrants, Labor Conflict, and the Coming of the Civil War, (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1992), 49–50; 54. ↵

- Rippley, The German-Americans, 52–53. ↵

- Levine, The Spirit of 1848, 233. ↵

- Levine, 237. ↵

- Levine, 233–234. ↵

- Levine, 226. ↵

- Rippley, 52–53. ↵

- Tolzmann, 200. ↵

- Levine, 250. ↵

- Tolzmann, 200–201. ↵

- Tolzmann, 202. ↵

- Bayard Quincy Morgan, "Carl Schurz." In The Forty-Eighters: Political Refugees of the German Revolution of 1848, edited by A. E. Zucker, (New York: Russell & Russell, 1950/1967), 221; 224–227. ↵

- Morgan, "Carl Schurz," 228. ↵

- Morgan, 229. ↵

- Ella Lonn, “The Forty-Eighters in the Civil War.” In The Forty-Eighters: Political Refugees of the German Revolution of 1848, edited by A. E. Zucker, (New York: Russell & Russell, 1950/1967), 189–191. ↵

- Wikipedia contributors, "Carl Schurz," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia (accessed December 21, 2023). ↵

- Rippley, 58. ↵

- Lonn, “The Forty-Eighters in the Civil War,” 184. ↵

- Levine, 256. ↵

- Wikipedia contributors, "1860 United States census," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed July 11, 2023); "1860 Census: Population of the United States". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 11, 2023. (Used to determine population of persons of German ancestry in 1860.) ↵

- Tolzmann, 209–210. ↵

- Kamphoefner, 190–191. ↵

- Tolzmann, 210. ↵

- Rippley, 68–69. ↵

- Rippley, 70–71. ↵

- Tolzmann, 222–224. ↵

- Christina A. Ziegler-McPherson, The Great Disappearing Act: Germans in New York City, 1880–1930, (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2022), 5; 9. ↵

- Ziegler-McPherson, Great Disappearing Act, 2–4. ↵

- Ziegler-McPherson, 3. ↵

- Tolzmann, 232–233. ↵

- Ziegler-McPherson, 22; Tolzmann, 234. ↵

- Ziegler-McPherson, 6. ↵

- Ziegler-McPherson, 14–15. ↵

- Ziegler-McPherson, 15–22. ↵

- Ziegler-McPherson, 22–23. ↵

- Ziegler-McPherson, 4. ↵

- Ziegler-McPherson, 134. ↵

- Ziegler-McPherson, 119-120. ↵

- Tolzmann, 270–271. ↵

- Ziegler-McPherson, 3-4. ↵

- Tolzmann, 280–290. ↵

- Ziegler-McPherson, 137. ↵

- Tolzmann, 334–335. ↵

- Russell A. Kazal, Becoming Old Stock: The Paradox of German-American Identity, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004), 273. ↵

- Tolzmann. ↵

- Tolzmann, 349–352. ↵

- Tolzmann, 353. ↵

- Wikipedia contributors, "Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed September 7, 2023). ↵

- Tolzmann, 353–355. ↵

- Tolzmann, 355–356. ↵

- United States Census Bureau, “German-American Day: October 6, 2022,” Press Release Number CB22–SFS.142, (accessed September 9, 2023); Wikipedia contributors, "German Americans," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed September 9, 2023). ↵

- Kazal, Becoming Old Stock, 1. ↵