11 Eastern European Jews

1. Jewish Exodus from Eastern Europe

1.1 Pushed to the Brink

1 Among the largest groups to immigrate to the U.S. during the last two decades of the 19th century and the first two decades of the 20th century were the Jews of Eastern Europe, the overwhelming majority of whom were fleeing the Russian Empire. Although Jews had come to colonial America in small numbers, mostly from Spain and Portugal, there were only about 250,000 Jews in the United States in 1880, and only about 50,000 were from Eastern Europe. The mass exodus of Jews from Eastern Europe only began in earnest in 1881, a year that Irving Howe has characterized as “a turning point in the history of the Jews as decisive as that of 70 A.D., when Titus’s legions burned the Temple at Jerusalem, or 1492, when Ferdinand and Isabella decreed the expulsion from Spain.”[1] By 1924, when Congress drastically cut immigration from Eastern Europe to almost nothing, there were roughly four million Jews in the U.S.—three million of them Eastern Europeans, including their children and grandchildren.[2]

2 For centuries the Jews of Eastern Europe had faced periods of discrimination and persecution followed by periods of relative tolerance, depending upon the ruling authorities. For instance, compared with the Russian Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was relatively more tolerant toward its Jewish population, especially after the issuance by Emperor Joseph II of the Edict of Tolerance (1782). Although the edict did seek to assimilate Jews into Austrian society by interfering with community formation and pressuring Jews to abandon their unique cultural, linguistic, and religious commitments, it nevertheless granted Jews certain rights and freedoms, including the right to own property, engage in various trades, pursue higher education, etc.[3]

3 On the other hand, the treatment of Jews was particularly severe in Russia, where they were forced to live in the so-called Pale of Settlement, “an area of about 386,000 square miles, from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea. By 1897, roughly 4.9 million Jews—94 percent of the total Jewish population of Russia—were crowded into the Pale of Settlement.[4] Jews were forbidden from venturing beyond the Pale, and they were prohibited from owning land. They were forced to live in increasingly crowded urban areas, earning livelihoods as merchants and artisans of which there were too many to make their work economically viable. Moreover, life in the shtetls, the Jewish towns, where anti-Semitic violence was a constant threat, made life in Russia intensely insecure. “Especially dreaded [in shtetl and big city alike] were the pogroms—massacres of Jews and the destruction of their shops and synagogues.”[5]

4 However, Jews took heart during the reign of Alexander II, Czar of Russia from 1855 to 1881, who had been relatively liberal and tolerant. For instance, among other reforms, “he had opened the doors of the universities to some Jews; [and] permitted Jewish businessmen to travel in parts of Russia from which they had been barred.” His policies had Russian Jews clinging to “modest hopes of winning equal rights as citizens.” But these hopes were dashed when Alexander II was assassinated and life took a disastrous turn under the anti-Jewish policies of Alexander III. Within weeks of the new czar’s accession to the throne, “a wave of pogroms … spread cross Russia.” With all promise of stability, peace, well-being, and equality suddenly gone, the Jews of Russia began their exodus.[6]

5 Between 1881 and the beginning of World War I, “approximately one third of the east European Jews [the vast majority of them from the Russian Empire] left their homelands—a migration comparable in modern Jewish history only to the flight from the Spanish Inquisition.”[7] Over a million Russian Jews emigrated between 1880 and 1910, followed by another million over the next decade. Most of them made their way to the United States. Although the mass exodus peaked between 1905 and 1906, it came to an end only in the 1920s, when the U.S. began to drastically restrict immigration.[8]

1.2 Arduous Journey Out of Russia

1 To escape from Russia, migrants had to first make their way to western Europe. Those living in the western or northwestern Russia might sneak across the German border and head to Berlin where they would regroup for the journey to major transatlantic ports: Hamburg or Bremen (Germany), Rotterdam or Amsterdam (Holland), or Antwerp (Belgium). Those in southern Russia or the Ukraine, generally crossed (illegally) over the Austro-Hungarian border and traveled by train to Vienna or Berlin and thence to the northern ports.[9]

2 Jews living in the Austro-Hungarian empire could cross legally to Germany and head to Berlin, while the preferred route of those in Romania was via Vienna or Frankfurt am Main to the ports of Holland. Those who did not want to risk illegal border crossings would take more roundabout journeys.[10]

3 The journey across borders was anything but simple; in fact, it was fraught with countless risks, especially for those without legal passports. Such migrants were especially vulnerable to all manner of exploitation: threats, intimidation, robbery, trickery, etc. Even legal travelers faced many indignities: interrogation, inspection, disinfection, quarantine for suspected disease—all of this on top of the general hardships of migration that often entailed discomfort and hunger. But as Irving Howe reminds us, “discomfort, hunger, humiliation, were as nothing to the one absolute fear gripping all emigrants: that one of their family might be sent back or kept off the boat after the dockside inspection.”[11]

2. Crossing to America

1 After the ordeal of the journey from eastern Europe to the ports of northern Europe came the ordeal of crossing the Atlantic by ship. Many migrants from the era left written accounts of their experiences traveling in steerage—the part of the ship reserved for passengers with the cheapest tickets. These accounts vividly describe experiences of disgust, misery, and despair in an environment pervaded by darkness, filth, suffocating heat, stench, and noxious vapors. The conditions often exacerbated passengers’ natural tendencies to seasickness, inducing fits of vomiting, followed by general stupor. Such experiences, however, seem to have been more typical of steerage before the turn of the century, after which the duration of voyages became much shorter and the quality of accommodations greatly improved, so travelers in the 20th century may have been spared the miseries of those who had come earlier.[12]

2 At the end of the long journey lay the prospective immigrant’s last obstacle, that of getting through the gauntlet of interrogators and multiple medical examiners at Ellis Island. Irving Howe describes the first stage in this series of ordeals:

On Ellis Island they pile into the massive hall that occupies the entire width of the building. They break into dozens of lines, divided by metal railings, where they file past the first doctor. Men whose breathing is heavy, women trying to hide a limp or deformity behind a large bundle—these are marked with chalk, for later inspection. … (A veteran inspector recalls: “Whenever a case aroused suspicion, the alien was set aside in a cage apart from the rest … and his coat lapel or shirt marked with colored chalk, the color indicating why he had been isolated.”) One out of five or six needs further medical checking—H chalked for heart, K for hernia, Sc for scalp, X for mental defects.[13]

3 This was only the first medical examiner that the immigrant had to get past. A second one, a specialist in “contagious and loathsome diseases,” examined each immigrant for leprosy, venereal disease (which required examinees to expose their private parts) and favus, “a contagious disease of the skin, especially of the scalp, due to a parasitic fungus.” And after that, a third doctor checked under each examinee’s eye lid for signs of trachoma, an infectious disease of the eye.[14]

4 After the medical examinations came more interrogations: “multilingual inspectors ask[ed] about character, anarchism, polygamy, insanity, crime, money, relatives, work. You have a job waiting? Who paid your passage? Anyone meeting you? Can you read and write? Ever in prison? Where’s your money?”[15]

5 It took about one day for the average person to pass through Ellis Island, but those detained for medical or other reasons usually had to stay for one or two weeks while waiting for their cases to be heard by boards of special inquiry that would determine their ultimate fate.[16] If they were fortunate, they would be admitted into the country; if not, they would be sent back to Europe.

6 After clearing the immigration inspections at Ellis Island, most Eastern European Jews headed for New York’s Lower East Side. In 1880, the area already had a small German Jewish quarter, dating from the early 19th century, but it was otherwise dominated by Irish and German immigrants. With the massive waves of Russian Jews joining the mix, the Lower East Side soon became the most densely populated area of the city, and by 1905, the Jewish population of the Lower East Side stood at about a half million[17]

3. Distinctive Features of Jewish Immigration

1 As Susan Glenn has noted: “The economic, political, and social oppression of eastern European Jews shaped the nature of their emigration, giving it several distinctive qualities.” For one thing, the vast majority of Jews who left Russia did so with no intention of ever returning. This contrasted sharply with many other emigrants from eastern and southern Europe, such as Italians, Poles, and Hungarians, many of whom intended to emigrate only “to earn enough money to make a better life for themselves when they eventually returned to their land of origin.” Indeed, “the return rate for non-Jews from eastern and southern Europe … ranged from 25 to 60 percent.” For instance, nearly 64 percent of Hungarians and 56 percent of Italians eventually returned to their homelands while “the estimated return rate for eastern European Jews was a mere 2 to 3 percent.”[18]

2 Furthermore, because Eastern European Jews did not intend to return, women and children comprised a significant proportion of Jewish emigrants. Roughly 43 percent of Eastern European Jews were women as compared, for instance, to only 21 percent of southern Italians. According to Glenn: “Among all the immigrant groups who left for America in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, only the Irish sent a greater proportion of women (52.9 percent).”[19] Moreover, 25 percent of all Jewish immigrants were children so that unlike the mostly childless bachelor community of New York’s Chinatown, the Jewish quarter “had throngs of children.”[20]

3 Jewish immigrants were distinctive in other ways as well. While most of them were certainly poor, they were not necessarily uneducated. For instance, “80 percent of the men and 63 percent of the women who came between 1908 and 1912 were literate.” In addition, many were trained in a profession or handicraft. Among the Jews who declared an occupation, about 66 percent were skilled workers. By comparison, only 16 percent of Italians were similarly skilled.[21]

4 Finally, where a majority of immigrants among other ethnic groups were overwhelmingly male, Jewish immigration was primarily a family affair. Of course, as Susan Glenn has noted, “[r]arely was it possible for the entire family to emigrate at one time, and many years often elapsed before its members could be reunited.” Although during the first decades of Jewish migration, men often did lead the way, just as with most other immigrant groups, later Jewish migration patterns became more dynamic and more variable, with women, particularly working-age daughters in the sewing trades sometimes becoming “the avant-garde of the overseas movement.” As Glenn has further articulated it:

Before the turn of the century the husband usually made the journey first, sent for the working-age children, and eventually arranged for his wife and the youngest family members to emigrate.

But after a network of relatives and countrymen and countrywomen upon whom they could depend was established in American cities, Jewish families … were [increasingly] willing and found it practicable to send one or more children including their working-age daughters, in advance. Artisans, factory workers, merchants, and others who found it difficult to make a living in Russia began to allow their daughters to travel to America ahead of the rest of the immediate family.

Daughters who might have otherwise entered the sewing trades or tried to find factory work in Russia left for the United States, where it was hoped they could earn a better living. Although the trades in Russia were overcrowded, the clothing industry in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, and other cities was rapidly expanding. Families hoped their daughters would find employment and earn enough money to bring over the rest of the household.[22]

5 Jewish immigration patterns were thus decidedly different from those of almost every other immigrant group, with the exception of the Irish, who also tended to immigrate to the U.S. with no intentions of returning to the home country, and among whom unmarried daughters often played a similar avant-garde role.

4. Life on New York’s Lower East Side

1 As the population of Jewish immigrants swelled in New York’s Lower East Side, some Jews felt almost as if they were living just as they had in Russia, that is, residing and working within a narrowly drawn area and interacting only with fellow Jews. On the other hand, if it seemed in some ways as though they had replicated the shtetl or ghetto back home, the pace of life was not nearly as leisurely. On the contrary, it had become greatly accelerated, with crowds of noisy people going in all directions, shouting, and working energetically at earning a livelihood. Peddlers with their packs or pushcarts seemed to be everywhere outside cafes and theaters trying to sell a variety of items: bandanas, collar buttons, hats, matches, tin cups, and suspenders, or fruits and vegetables. “The Jewish peddler soon became a figure of Jewish-American folklore.”[23]

2 However, street peddling was not the predominate line of work it might have appeared to be. In fact, an 1890 survey of Jewish workers in New York City suggested that only 10 percent of them were peddlers, while 60 percent worked in the garment industry. Indeed, as mentioned earlier, the vast majority of Russian Jews came to the U.S. with skills, especially in the sewing trades. They came at a time, moreover, when custom, tailor-made clothing was giving way to mass-produced clothing. Garment makers were using new inventions like “the Singer sewing machine, the electric cutting knife, and the buttonhole machine,” and they were employing assembly-line production methods. There was no shortage of work. But the work was dull, repetitive, and physically punishing, as workers stayed bent over their tasks in hot, dark “sweatshops,” heavily supervised and with very few breaks throughout workdays that were from eleven to sixteen hours long.[24]

3 Peoples’ residences were hardly any more pleasant than the sweatshop factories. A typical tenement was located in a brick building six or seven stories high. On every floor were four apartments, two at each end of a hall. The only direct light for each apartment was either a window facing the street or one overlooking a small backyard. Buildings were separated by five-foot wide air shafts. Eighteen to twenty families could live in one building, and the total population could range from 100 to 150 people. Most of the tenements had just two toilets per floor and no baths. Desperate for light and fresh air, people liked to escape on hot summer evenings to parks, such as Jackson Park, a large open area which once stood near the East River, “where a small band occasionally played and milk was dispensed at a penny a glass.”[25]

4 To foster community, Jews on the Lower East Side formed landsmanschaftn—”lodge[es] made up of persons coming from the same town or district in the old country,” di alte heym (the old home), as they called it.[26] People also sought company and conversation in the public bathhouses as well as the neighborhood delicatessens and candy stores. Jewish intellectuals met for tea and to debate philosophical and political ideas in cafés with names like Schreibers and Café Royale before rushing off to hear lectures at Cooper Union.[27]

5 But ultimately, Jews living in the tenements of the Lower East Side, particularly the younger generations, sought to distance themselves from immigrant customs and ethnic cultural traits that marked them as “greenhorns.” They sought to Americanize themselves by dressing according to the latest American fashions, by giving up Yiddish in favor of English, and eventually by leaving the Lower East Side.[28] Even so, as Irving Howe has reminded us:

This did not mean ceasing to be a Jew or to identify with Jewish interests; it did not even mean ceasing to live among Jews. It meant, simply, moving away. Moving away from immigrant neighborhoods in which Yiddish still prevailed; moving away from parents whose will to success could unnerve the most successful sons and daughters; moving to “another kind” of Jewish neighborhood, more pleasing in its physical look and allowing a larger area of personal space; and moving toward new social arrangements: the calm of a suburb, the comfort of affluence, the novelty of bohemia.[29]

6 Increasingly, the upwardly mobile younger generation dispersed to the outlying districts of Brooklyn, the Bronx, and beyond, where “they could live on tree-lined streets still bordered by open fields and vacant lots.”[30]

5. Revolution in the Clothing Industry

1 In the late 1800s, German Jews dominated the garment industry. As the Jewish newcomers from Russia arrived, many of them also became contractors and manufacturers. “Together, the German and Russian Jewish garment makers revolutionized the way clothes were made and what Americans wore.” Drawing on their tailoring skills and innovative techniques, they streamlined production. It became possible to make clothing both more quickly and more cheaply. The transformation democratized fashion, allowing for the mass production of stylish and affordable clothing, enabling a broader range of Americans to keep up with changing trends. Thanks to Russian Jewish garment workers, the average American girl could now be a “tailor-made” girl.[31]

2 But the garment industry was extraordinarily exploitative. The hours were long, the wages were low, and the working conditions were deplorable—hot, poorly ventilated, overcrowded, and unsafe. And the industry was extremely competitive, leading employers to be continually trying to find ways to cut production costs, which often resulted in downward pressure on the already low wages of the young women who formed a significant part of the workforce. Particularly frustrating for many young women working in the garment industry, who also tended to be attracted to the new urban consumerism of the times, was the fact that they did not earn enough to buy the fashionable clothing that they were producing and that they desired for themselves.[32] Despite the expense, however, many young workers managed to scrap together the money to dress fashionably.

6. Jewish Labor Movement

1 The political convictions of Russian Jewish immigrants were greatly influenced by various socialist ideologies absorbed back in Russia, including principles of collective action, workers’ rights, and social justice. It is, therefore, not surprising that Russian Jews were instrumental in the establishment of a robust labor movement, particularly in industries like the garment trade. They were instrumental, for instance, in establishing the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA).[33]

2 A distinctive feature of Jewish labor activism was the significant role that women played. They were often the majority of the workforce in garment factories, and the poor working conditions and exploitation they faced there strongly motivated them to action. One of the most dramatic stories of Jewish women’s activism is that of the Uprising of the Twenty Thousand, as it came to be known.

3 On November 22, 1909, twenty thousand shirtwaist (i.e. blouse) makers, most of them young women in their teens and early twenties, about two thirds of them Jewish and many of the rest Italians, went on strike. They were no longer willing to tolerate the many tyrannies that they had to endure in the workplace, from sexual discrimination to class exploitation. Limited strikes had already been tried against several firms—Triangle Shirtwaist Company and Leiserson Company in particular—but they had failed when the companies used strikebreakers and thugs to intimidate the women. Before the uprising of the twenty thousand, a mass meeting had been called to discuss the situation, and many leading labor leaders had given speeches about the need for solidarity, preparedness, and so on. On this particular occasion, however, a young woman named Clara Lemlich made history in a way that would be remembered and retold many times over in the history of Jewish labor in America. Lemlich made her way to the speaker’s platform and called, in Yiddish, for an end to idle talk:

I am a working girl, one of those striking against intolerable conditions. I am tired of listening to speakers who talk in generalities. What we are here for is to decide whether or not to strike. I offer a resolution that a general strike be declared—now.[34]

4 “A contagion of excitement swept the meeting,” and the general strike was on. It went on for weeks. Most of the shops were closed. A few of them tried to continue with scab labor, but the Jewish socialists threw themselves into the fight, and “the Women’s Trade Union League sent help to the picket lines, sharing blows and abuse with the Jewish and Italian girls.” The employers hired goons and thugs to beat the strikers and smuggle in scab labor, and when the cops showed up, the goons ran off, and the cops arrested the strikers! “The strike dragged on until mid-February 1910, and was finally settled with improvements in working conditions but without the formal union recognition for which the ILGWU had held out.”[35]

5 As Irving Howe has expressed it: “What the girls began, the men completed.” Five months after the shirtwaist makers strike, the cloak makers declared a general strike. Where the shirtwaist makers strike had involved 20,000 workers in a spontaneous uprising, the cloak makers strike was three times as large and carefully planned. Prior to the strike, a “$25,000 strike fund was collected, with about two thirds of that sum to be distributed as weekly strike benefits. On July 2 and 3, a secret vote of all the locals in the cloak industry favored the strike by 18,771 to 615. On July 7 the strike began. … It was precise, orderly, well-managed: something new among the immigrant workers.”[36]

6 The strikers wanted a forty-nine-hour week; the employees offered a fifty-three-hour week. As the two sides began to meet, wage demands also began to seem negotiable. “But the one point that seemed beyond compromise was a union demand that the employers bind themselves to hire only union members,” so the strike dragged on throughout the summer, causing suffering among the workers and steep financial losses among the smaller employers. Finally, on September 2, a settlement was reached the greatly improved situation of cloakmakers: “a fifty-hour week, wage increases, abolition of inside subcontracting, and a ‘preferential union shop’ that in practice” closely approximated the “closed shop” that the union desired. “[B]y 1910, one could speak of a Jewish working class, structured, disciplined, self-conscious, and with a much stronger tie to socialist politics than characterized the American workers.”[37]

7 “After 1910, strike followed strike, one after the other, in all the Jewish industries,” but in the spring of 1911, tragedy struck the Lower East Side of New York when the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, at the edge of Washington Square, one of the largest shops in the city, caught fire. Within eighteen minutes, 146 mostly young Jewish and Italian women, unable to escape, were burned to death. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, perhaps more than any other disaster in labor history, dramatized the dangerous conditions under which many workers labored in the early 20th century. “It was from such experiences that the immigrant Jewish working-class emerged in America.”[38]

7. Transition to Middle-Class

1 In the 1930s, about half of all American Jews of Eastern European descent still worked in manufacturing, although among the second generation, a slightly higher percentage had become clerks, office workers, salesmen, and the like. However, the economic landscape changed dramatically between the end of the 1930s and the mid-1950s, raising the children and grandchildren of the Eastern European Jews who had immigrated between 1880 and 1923 to about the same level previously achieved by the German Jews.[39]

2 Between the World Wars, the proportion of American Jews engaged in middle-class occupations grew considerably, and the types of middle-class jobs occupied by Jews gradually changed as well, as second and third generation American Jews in increasing numbers entered clerical services, public agencies, and the professions. By 1957, over 55% of Jews in the U.S. were either professionals, technicians, managers, public officials, or business owners. Only 18.2% worked in manufacturing. Moreover, “the total of professional and semi-professional workers among Jews was almost twice as high as among non-Jews” (27.6% compared to 14%). At the same time, over 80% of Jewish youth would eventually be attending college.[40]

8. Language and Culture

8.1 Yiddish

1 The primary language of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, particularly those of Ashkenazi (Central European) heritage, was Yiddish. Linguistically, Yiddish is a West Germanic language that emerged in Central Europe during the 9th century. Exhibiting elements of Hebrew and Aramaic as well as traces of Slavic and Romance languages, Yiddish was written in Hebrew characters.[41]

2 Yiddish played a significant role in Jewish America during the late 19th and early- to mid-20th century, connecting Jewish immigrants to their heritage and their European roots and remaining an essential aspect of Jewish identity in America. Yiddish facilitated daily interactions, commerce, and community life, allowing immigrants to communicate with one another, even if they spoke different native languages from their home countries. It played a pivotal role in labor activism, with labor unions, socialist movements, and labor rallies often utilizing Yiddish for mobilization and advocacy. Yiddish was also a rich medium for artistic expression within the new American context. Jewish immigrants or their children produced a homegrown Yiddish literature and poetry. Yiddish theater thrived in major cities, and Yiddish newspapers and magazines provided information and entertainment to Yiddish-speaking communities.

3 Although the prevalence of Yiddish eventually declined, especially after World War II, its impact on American culture is still evident today, with many Yiddish words and phrases having entered the American English lexicon. Here are just a few typical examples:

| Yiddish |

English |

| bagel | a dense bread roll with a hole in the middle |

| chutzpah | audacity or boldness |

| goy | a non-Jewish person |

| kibitz | to chat idly; to give unsolicited advice |

| kvetch | to complain or whine |

| mazel tov | congratulations; good luck |

| mishmash | a hodgepodge or jumble |

| nosh | to snack or eat lightly |

| oy vey | an expression of dismay or exasperation |

| putz | dumb or worthless person (slang for penis) |

| schlep | to carry something |

| schmaltz | sentimentality, excessive emotion |

| schmooze | to chat or converse informally |

| shtick | a gimmick or a comic routine |

| tuchus | a person’s buttocks |

8.2 Entertainment and Popular Culture

1 The first Eastern European Jewish immigrants, like all immigrants, naturally had to be concerned with putting bread on the table and keeping a roof over their heads. But as Irving Howe has explained:

In every gang of kids spilling onto the Jewish streets of 1900 or 1905—kids whose mothers hoped they would grow up to become manufacturers, accountants, and doctors—there was bound to be one who dreamed of “breaking in” with a comic act or vaudeville troupe. It was a desire that often left him uneasy: try explaining to immigrant parents that their darling son wants to become a “bum” who cracks jokes in gentile theatres![42]

2 However, there were more than a few young Jews who followed the perilous path of showbiz. Their names were once very well known, even if they aren’t so familiar today to the youngest amongst us: “Al Jolson, George Jessel, Eddie Cantor, Sophie Tucker, Fanny Brice, Ben Blue, Jack Benny, George Burns, George Sydney, Milton Berle, Ted Lewis, Bennie Fields, many others. And there are the hundreds,” as Howe has observed, “who played the small towns, the ratty theatres, the Orpheum circuit, the Catskills, the smelly houses in Brooklyn in the Bronx.”[43]

3 As unexpected as the proliferation of Jewish comics, singers, and dancers might have seemed, Howe has suggested some explanations. For one thing, “[T]he immediate Yiddish past offered some models” in particular, “the badkhn,” a kind of master of ceremonies at wedding festivities, whose primary role was to entertain the wedding guests with humorous and often satirical speeches, as well as “the jester, the fiddler, [and] the stage comedian.” But perhaps more significant was that “by the early 1900s a good portion of the theatrical business in New York” and beyond was under Jewish ownership and influence. This created opportunities in a relatively safe environment where Jewish performers could thrive and make their mark based on their talents.[44]

4 Nor was the influence of Jewish immigrants and their descendants limited to stand-up comedy and vaudeville. In the world of music, Jewish composers and musicians like George Gershwin, Irving Berlin, and Leonard Bernstein became iconic figures in American music; their compositions, from jazz to Broadway tunes, have left an indelible mark on the American cultural landscape.

5 In literature, Jewish authors like Isaac Bashevis Singer, Saul Bellow, and Philip Roth have garnered international acclaim for their novels, many of which explore themes of identity and the Jewish experience in America.

Novelists: Isaac Bashevis Singer, Saul Bellow, and Philip Roth

6 In theater, too, Jewish playwrights including Arthur Miller, Neil Simon, and Wendy Wasserstein have become synonymous with the American stage, creating plays and productions that reflect the diversity and complexity of American life.

Playwrights: Arthur Miller, Neil Simon, and Wendy Wasserstein

7 The influence of American Jews in the world of movies is another remarkable story. Jewish filmmakers, actors, producers, and screenwriters have all helped shape American cinema and the global film industry. In the early days of Hollywood, Jewish moguls like Louis B. Mayer, Adolph Zukor, and Carl Laemmle established major studios such as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), Paramount Pictures, and Universal Pictures.

Movie Studio Moguls: Louis B. Mayer, Adolph Zukor, and Carl Laemmle

8 Jewish directors, screenwriters, and producers, such as Steven Spielberg, Stanley Kubrick, Woody Allen, and Joel and Ethan Coen have created timeless classics and continue to influence the world of film with unique visions and storytelling prowess.

Movie Directors: Steven Spielberg, Stanley Kubrick, Woody Allen, and the Coen brothers

9 And actors of Jewish descent such as Lauren Bacall, Kirk Douglas, Dustin Hoffman, and Barbra Streisand have received critical acclaim and numerous awards for their outstanding performances in a wide range of film genres.

Actors: Lauren Bacall, Kirk Douglas, Dustin Hoffman, and Barbra Streisand

10 Unfortunately, a brief survey like this one cannot even begin to adequately enumerate the countless Jewish American contributions to the U.S. arts, entertainment, and popular culture scene.

9. American Judaism

1 By the time Eastern European Jews began to arrive in the United States in the late 1800s, earlier generations of Jews, mainly from western and central Europe, had already been adapting Judaism to a New World context. However, since the purpose of this chapter is to tell the story of the Eastern European Jewish immigration, we will skip over the history of Judaism in America prior to 1880.

2 As Jonathan Sarna has observed, many Eastern European Jews who immigrated after 1880 were likely to have abandoned their religious faith years earlier, but even if that was not always literally the case, the process of immigration tended to loosen Eastern European Jews from their religious moorings.[45]

3 At any rate, in the United States, Eastern European Jews encountered a religious world radically different from the one they had known in the home country. In Europe, their religion had virtually defined them, politically; “it was an inescapable element of their personhood. They were taxed as Jews,” drafted into the military as Jews, married or divorced according to Jewish law, by rabbis authorized by the state, and their passports and other official documents were stamped with their religious affiliation. Moreover, there were usually few impediments to their ability to observe Jewish laws and customs if they wished. In fact, the only way to cast off a Jewish identity was to convert to Christianity. [46]

4 On the other hand, religion in the United States “was a purely private and voluntary affair,” at least in theory, “totally outside of the state’s purview. Nobody forced Jews to specify their religion; they were taxed and drafted as human beings only. When a Jew married or divorced in America, it was state law, not Jewish law, that governed the procedure; rabbinic involvement was optional. Indeed, rabbis enjoyed no social status whatsoever in the United States. As a result, Judaism proved easy enough to abandon, but, in the absence of state support, difficult to observe scrupulously.”[47]

* * *

5 Among the Jews arriving from Eastern Europe, three basic orientations seemed apparent. Some Jews were “learned and pious,” and upon arrival, they tried to maintain their Eastern European practices and institutions. They often “differentiated themselves from others in the way they dressed—head coverings, beards, modest attire—and they attempted to regulate their lives according to the dictates of Jewish law and the rhythms of the Jewish calendar. They took less-well-paying jobs, like piecework or Hebrew teaching, in order to keep the Sabbath and the Jewish holidays sacred,” and they kept alive the hope that it would be possible “to re-create in America the kinds of traditional religious institutions that they believed Jewish life demanded.” On the other hand, “they did not expect their children, who attended public schools and played with non-observant Jews, to follow in their footsteps.”[48]

6 “A second type of immigrant was the hustler, known as a shvitser in Yiddish.” Their primary aim was to make money, and if that meant abandoning elements of their faith and upbringing, even their families, that’s what they did. They cared more about social and economic success than they did about preserving Judaism[49]

7 Finally, there was “the freethinking radical” who came with “a hardened political ideology and a predetermined social agenda. Raised under tyrannical regimes, these revolutionaries—socialists, anarchists, Communists, and the like—tended to view America and its political institutions through the distorting lens of East European politics.” Their mission was to promote the betterment of life in society. “They hated the very institutions that the hustlers and the pious Jews held most dear, and they professed not to care even if Judaism as a religion disappeared from the earth.”[50]

8 But the average Eastern European Jewish immigrant, according to Sarna, combined aspects of all three orientations. Like the learned and pious, they sought to preserve Judaism, “but they focused on what they saw as its major tenets and practices, allowing the rest to slip.” Like the hustler, they strove “to make money and forge ahead,” but not with the one-sided zeal of the hustler. And they shared the radical’s “vision of a better future,” but without the political extremism and revolutionary fervor. “They struggled, in short, to find some balance between their ancient faith, their economic aspirations, and their utopian ideologies—a halfway covenant between tradition and change. In so doing, even without realizing it, they followed in the footsteps of generations of earlier immigrants to America’s shores, from the Puritans onward.”[51]

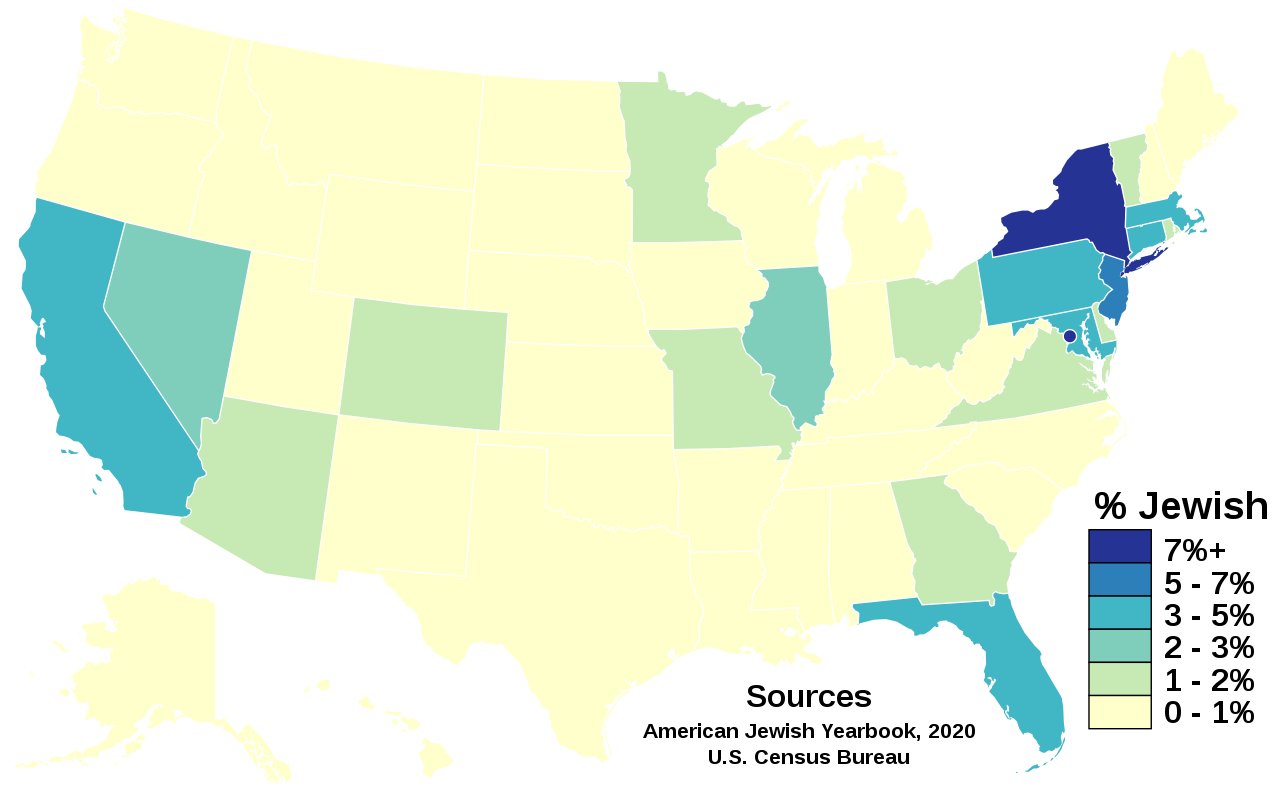

10. Where American Jews Live Today

Chapter 10 Study Guide/Discussion Questions

Activity 10.1

Based on your understanding of subsections 1–3 of the chapter, answer and discuss the following questions with one or more fellow readers.

- Describe the life circumstances of Jews in Eastern Europe in the 19th century.

- What was it like to emigrate from Eastern Europe during that time?

- Describe the transatlantic crossing.

- Compare and contrast the 19th-century Jewish migration with that of other European groups that you have studied.

Activity 10.2

Based on your understanding of subsections 4–7 of the chapter, engage with the following and discuss your responses with one or more fellow readers.

1. Create a table like the one below to describe life on the Lower East Side

| The streets

|

|

| The living conditions

|

|

| Typical occupations

|

|

| Working conditions

|

2. How did the lives of second and third generation Jews differ from that of the immigrant generation?

Activity 10.3

Based on your understanding of subsections 8–9 of the chapter, answer and discuss the following questions with one or more fellow readers.

- What is Yiddish? In which various aspects of life did Yiddish play a significant role? Explain.

- To what forms of art and entertainment did Jewish Americans contribute? With which Jewish artists or entertainers are you familiar?

- Describe several different orientations that characterize the religious life of American Jews.

Media Attributions

- Bychawa Shtetl © Author Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Steerage on the Kaiser Wilhelm © Alfred Stieglitz is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1898 Photo of Orchard Street on New York’s Lower East Side © Tenement Museum is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Lower East Side Tenements © Moncrief is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Six Shirtwaist Strike Women, 1909 © Kheel Center is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Clara Lemlich © Kheel Center is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire © Author Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Yiddish WWI Poster © Charles Edward Chambers is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Fanny Brice © NBC Radio is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Gallery Images – Famous Jewish American Composers

- George Gershwin © Mishkin is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Irving Berlin © Al Aumuller is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Leonard Bernstein © Jack Mitchell is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Gallery Images – Famous Jewish American Novelists

- Isaac Bashevis Singer © Bernard Gotfryd is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license. Used with permission under Fair Use

- Saul Bellow © Jeff Lowenthal is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Philip Roth © Nancy Crampton is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Gallery Images – Famous Jewish American Playwrights

- Arthur Miller © Eric Koch/Anefo is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Neil Simon © Solters/Sabinson/Roskin agency is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Wendy Wasserstein © Author Unknown is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license. Used with permission under Fair Use

- Gallery Images – Famous Jewish American Movie Moguls

- Louis B. Meyer © Los Angeles Times is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Adolph Zukor © Apeda Studio is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Carl Laemmle © Universal is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Gallery Images – Famous Jewish American Movie Directors

- Steven Spielberg © Romain DUBOIS is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Stanley Kubrick © Warner Bros, Inc. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Woody Allen © Colin Swan is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Coen Brothers © Rita Molnár is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Gallery Images – Famous Jewish American Actors

- Lauren Bacall © Author Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Kirk Douglas © Author Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Dustin Hoffman © Author Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Barbra Streisand © Author Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- American Jews by state © Abbasi786786 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Irving Howe, World of Our Fathers: The Journey of the East European Jews to America and the Life They Found and Made (New York: Open Road Media, Kindle Edition, 2017/originally published, 1976), 27. ↵

- Roger Daniels, Coming to America: A History of Immigration and Ethnicity in American Life, 2nd edition, (New York: Harper Perennial, 2002), 223. ↵

- Wikipedia contributors, "History of the Jews in Austria," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed September 24, 2023). ↵

- Howe, World of Our Fathers, 59. ↵

- Ronald Takaki, A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America, revised edition, (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2008), 262–263. ↵

- Howe, 27–30. ↵

- Howe, 61. ↵

- Daughters of the Shtetl, (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991), 42–43. ↵

- Howe, 63. ↵

- Howe, 64. ↵

- Howe, 78. ↵

- Howe, 80–85. ↵

- Howe, 86. ↵

- Howe, 86–87. ↵

- Howe, 87. ↵

- Howe, 88. ↵

- Howe, 122–123; Takaki, A Different Mirror, 267. ↵

- Daughters of the Shtetl, 47. ↵

- Glenn, 47. ↵

- Takaki, 267 ↵

- Takaki, 267. ↵

- Glenn, 48. ↵

- Takaki, 267–270. ↵

- Takaki, 271–274. ↵

- Takaki, 268–269. ↵

- Howe, 298. ↵

- Takaki, 269–270. ↵

- Takaki, 280–281. ↵

- Howe, 872. ↵

- Takaki, 289. ↵

- Takaki, 272. ↵

- Glenn, 164–165. ↵

- Howe, 472. ↵

- Howe, 474–475. ↵

- Howe, 477. ↵

- Howe, 477–479. ↵

- Howe, 479–480. ↵

- Howe, 484–486. ↵

- Howe, 961. ↵

- Howe, 962–963. ↵

- Wikipedia contributors, "Yiddish," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (accessed November 4, 2023). ↵

- Howe, 873. ↵

- Howe, 874. ↵

- Howe, 874. ↵

- Jonathan D. Sarna, American Judaism: A History, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 157. ↵

- Sarna, American Judaism, 159. ↵

- Sarna, 159. ↵

- Sarna, 158. ↵

- Sarna, 158. ↵

- Sarna, 158. ↵

- Sarna, 158–159. ↵