1 Indigenous America

1. First Nations

1 The Italian explorer, Christopher Columbus, is often credited as the person who “discovered” the Americas. In 1492, Columbus broke with European sea-going tradition and sailed west from Spain across the Atlantic Ocean under the theory that the earth was round and that he could therefore reach the Far East by sailing west. When he ran into the island that became known as Hispaniola (shared today by the Dominican Republic and Haiti), he thought he had landed somewhere in the East Indies—the islands in or near the Indian Ocean. That being the case, Columbus referred to the people he encountered as Indians. Although based on a geographical error, the term stuck and is still used today to refer to the Indigenous people of the Americas as a whole.

2 Of course, many critics of the claim that Columbus discovered America will point out that the Norse explorer, Leif Erikson, actually beat Columbus by about 500 years. Sometime around the year 1,000, historians believe, Erikson founded the short-lived colony of Vinland in present-day Newfoundland, Canada. However, this Norse colony did not survive.[1]

3 At any rate, from the perspective of America’s Indigenous peoples, both of these claims are Eurocentric distortions of world history. For by the time European explorers and settlers became aware of the Americas, both North and South America had already been discovered, explored, and settled for over 12,000 years (and perhaps for as long as 20,000 to 30,000 years).[2]

4 Well before the establishment of the United States, there were perhaps five to ten million Indigenous people organized in over six hundred independent tribes, bands, and groups inhabiting every part of North America. Each group had its own land base, economic system, government, social institutions, and cultural distinctiveness. Some groups lived by hunting, fishing, and gathering; others practiced intensive horticulture and trading. Some societies were organized in simple bands while others had complicated confederated governments. Hundreds of different languages were spoken representing as many as twelve distinct and unrelated linguistic families. Contrary to the way some early colonial sources portrayed North America, it was NOT an uninhabited wilderness.[3]

5 Now just to be clear, the descendants of the first inhabitants of the Americas are still here today, including in the lands currently comprising the United States. But unfortunately, continued Native presence is too often overlooked in discussions of the character of contemporary America. Here in the United States today, Indians are sometimes imagined as people who lived in the past, dressed themselves in picturesque clothing, and gave American settlers a hard time before finally being subdued in the final few years of the 19th century. Too many non-Indigenous people forget that like every other historical group, Indians moved on with the times, even as they had to endure more than their fair share of hardship and sorrow throughout the 20th century and now on into the 21st.

2. Speaking of Indians

1 Readers might notice that the term Indian appears quite a few times in the last section and wonder whether this is an appropriate, polite, or proper way to refer to the Indigenous peoples of America. Currently, a wide variety of terms are used to refer generically to the descendants of Indigenous people: Indians, American Indians, Native Americans, indigenous nations, tribal nations, Indian tribes, or in Alaska: Alaskan Natives, and interestingly, in Canada: First Nations.[4] It can all seem a bit confusing.

2 So—what is the correct terminology? Well, the National Museum of the American Indian has noted that American Indian, Indian, Native American, and Indigenous American are all acceptable when discussing Indigenous Americans in general.[5] However, not every Indigenous person will find every one of the above terms acceptable. Indeed, it might be the case that older generations of Native people are okay with the term “Indians” as a collective reference, while some among the younger generation are not, as illustrated by one of the young men who appears in the video clip at the end of this section.

3 At the same time, it is important to note that there is no such thing as a single, unitary group that comprises the Native American community. On the contrary, the American Indian population consists of a surprising number of tribes, which are historically and legally related to the United States as sovereign nations. The relationship between the U.S. and Indigenous nations will be discussed in more detail later. For the moment, the important thing to understand is the significance of this fact for the question of how Indigenous communities self-identify. To be competent cross-cultural communicators, non-Indigenous people need to understand that “indigenous communities expect to be referred to by their own names—Navajo or Diné, Ojibwe or Anishinaabe, Sioux or Lakota, Suquamish, or Tohono O’odham.”[6]

4 The above examples may leave some readers wondering why so many tribes seem to have multiple names. The reason is that when Europeans first encountered Native peoples, they named them in Spanish, or French, or English, and the tribes became known by those names. For example, Navajo comes from Spanish, while the “Navajo” people call themselves Diné in their own language; Sioux comes from French, while some “Sioux” people refer to themselves as Lakota or Dakota. (It is actually somewhat more complicated than this, but the current explanation should be sufficient for our present purposes.)

5 It may all seem hopelessly confusing to non-Native people, but the key takeaway is this: in interacting with particular Native people, or “when talking about Native groups or people, use the terminology the members of the community use to describe themselves collectively.”[7] When in doubt, be a good listener, and if that isn’t enough, one can ask: “how do the people of your community prefer to be identified by outsiders?” Or “what tribal name do members of your community consider proper and respectful?”

3. Nations, Not Minorities

1 Literally speaking, a minority group is a group of people who are present in fewer numbers than the members of some larger group. However, in social, political and legal discourse, “a minority group [also] refers to a category of people who experience relative disadvantage as compared to members of a dominant social group”[8] whether or not the minority group is smaller or larger than the dominant group.

2 In the United States, minority groups would include African Americans, Asian Americans, Hispanic Americans, women, gay and gender non-conforming people, to give just a few examples. Notice that American Indians are missing from the list of examples. By the definition quoted above, one might think that American Indians surely fit the definition of a minority group, and indeed they do. American Indians are both a numerical minority and a category of people who generally do not share the same power, privileges, rights, and opportunities as the White, Anglo majority. On the other hand, as political scientist David E. Wilkins has argued, because of the unique status of American Indian groups as sovereign nations vis-à-vis the United States, Indian peoples are not minorities in the same way that other racial and ethnic groups in the U.S. are.[9]

3 To appreciate this point, it is important to remember what has already been said about the state of affairs in North America when Europeans began colonizing it—i.e., there were over six hundred independent tribes, bands, and groups of Indigenous people already here. Some of the larger tribal nations coexisted with other tribes by means of sophisticated inter-tribal alliances. Some tribal nations were economically and militarily powerful. Tribes sometimes waged war against one another, but they also negotiated and maintained peace through the exercise of careful diplomacy.

4 After American independence, the United States entered this historical moment as just another nation among nations. At the time of the founding and for many years after, American leaders understood that as a practical matter no sovereign nation could bind another sovereign nation to its own laws and its will without great cost. Powerful though the United States was becoming as its population grew in the late 17th and 18th centuries, the power of Indian nations was not insignificant. Just as it was necessary to mediate disputes with sovereign nations like England, France, and Spain by negotiating treaties, the U.S. had to deal with the Indian tribes as the sovereign nations they were, by negotiating treaties.

5 A treaty is “a formal agreement … between two or more sovereign nations that create[s] legal rights and duties for the contracting parties.”[10] Thus, from the beginning, the relationship between Indian peoples and the United States “was a political one, steeped in diplomacy and treaties.”[11] No other racial or ethnic minority in the United States has or can have this kind of relationship with the federal government; for this reason, Indigenous legal scholars and activists continually emphasize the point that Indian peoples are not minority groups.

4. Legal Status of American Indians

1 The legal status of Indian tribes, and of individual Indians as well, is very complicated, so only a brief summary will be offered here.

2 To begin with, unlike all other U.S. citizens, American Indians’ legal status is not rooted in the United States Constitution, but instead in the more than five hundred treaties that the United States government negotiated with Indian tribes as sovereign nations. In other words, the relationship between Indian tribes and the United States is extra-constitutional (or outside of the Constitution) which is the fundamental document that established the framework of the U.S. government! In fact, there are only three direct references to Indians or Indian tribes in the Constitution:

- Article 1, section 2, clause 3: Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States … according to their respective numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the Whole number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other persons. [emphasis added]

- Article 1, section 8, clause 3: The Congress shall have Power to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes.

- The language in clause 3 of Article 1, section 2 (item #1 above) reappears in Section 2 of the 14th Amendment.

3 The rights of American Indians are therefore not directly guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution. On the other hand, according to Article 6 of the U.S. Constitution:

… all treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme law of the land, and the judges of every State shall be bound thereby, any thing in the Constitution or laws of any State to the contrary notwithstanding.

4 This means that “a tribe’s treaty rights are, at least in constitutional theory, the supreme law of the land, and should be subject to full protection under the Constitution’s rubric,”[12] thus affording Indians significant legal protections even if they fall short of the full protections explicitly guaranteed by the Constitution.

5 Another complexity concerns the question of U.S. citizenship. Today, Indians are U.S. citizens; however, from the time the Constitution was first adopted in 1789 and throughout the entire 19th century and even into the early 20th century, Indians were not legally considered to be U.S. citizens since they belonged instead to their own tribal nations. True, the U.S. Congress took actions from time to time suggesting that it eventually intended to extend citizenship to certain individuals and groups of Indians, often under the condition that they abandon their tribal citizenship and give up their claims to tribal property. Indian tribes often resisted efforts to get them to relinquish their sovereignty in exchange for citizenship status. It wasn’t until 1924 when Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act that Indians acquired citizenship status (whether they wanted it or not, and some did not).[13] At any rate, even after Congress made it clear that they were citizens, Indians were sometimes prevented from voting, a situation which was not explicitly addressed until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

5. Limitations on Tribal Sovereignty

5.1 The Doctrine of Discovery

1 You might think that the status of Indian tribes as sovereign nations would give Indian peoples the legal power to conduct their own affairs as they might wish, and to a limited extent, this is true. However, from the beginning, the U.S. government accepted the idea of Indian sovereignty only as a necessary expedient to avoid (or postpone) war. Otherwise, the U.S. government’s goal was the eventual domination of the continent by Anglo-European settlers, accompanied by the minimization or even elimination of Indian presence.

2 Today Americans generally take pride in the idea that we are governed by “rule of law.” One feature of this idea is that the decisions of governments are rightly made by applying known legal principles and respecting precedent (i.e., previously established decisions). But when European powers came to the Americas, they brought their legal theories with them, theories designed to help Europeans settle legal disputes among themselves. It might, therefore, come as a shock to Americans to learn that the basis for the laws and policies developed to govern the relationship between the Indian tribes and the United States was based on a dubious legal principle known as the Doctrine of Discovery.

3 The Doctrine of Discovery was developed primarily by Spain, Portugal, England, and the Catholic Church in the 15th and early 16th centuries to regulate the exploration and colonization of any lands occupied by non-European, non-Christian people. The Doctrine was based on medieval ideas regarding the inherent superiority of European peoples culturally, morally, and religiously, which they presumed gave them the God-given right to confiscate the lands of non-Christians.[14] (Spain relied on the same doctrine to subjugate the Indigenous peoples of Mexico.)

4 As surprising as it might seem, the Doctrine of Discovery still plays a role in American law today. For example, “the deed to almost all real estate in the United States originates from a federal title that itself came from an Indian title. … Furthermore, the three fundamental tenets of American Indian law, the plenary power, the trust responsibility, and the tribal diminished sovereignty doctrines … all arose from the Doctrine of Discovery.”[15]

5 The three principles mentioned above (plenary power, trust responsibility, and diminished sovereignty) all place limitations on Indian sovereignty. At the same time, they make it difficult to arrive at a clear understanding of Indian rights and of the U.S. government’s responsibilities to tribal nations as well as to their individual members. Especially confusing is that while certain principles (notably plenary power and trust) often work against tribal interests, there are other situations in which they work to the benefit of tribal interests. This is a complicated subject, but at the risk of oversimplification, a brief summary follows.

5.2 Plenary Power

1 Plenary means unqualified or absolute. In federal Indian policy and law, plenary power means that Congress recognizes itself as the only body with authority to manage Indian affairs; Congress may prohibit state governments from acting in Indian-related matters. Moreover, Congress has declared that its powers over Indian affairs are absolute, which means its authority to exercise control over Indian tribes, their lands and resources, is unlimited. It is hard to see how this principle is consistent with ideas like tribal sovereignty, or treaty rights as supreme law of the land, or with the fact that since 1924 Indians have been U.S. citizens, or with the very idea of democratic government.[16] From the perspective of tribal nations, this is all quite troubling, and it is not hard to see why.

2 On the other hand, because of its plenary power, Congress is able to make laws that provide Indians unique benefits which “other groups and individuals are ineligible for—medical care, educational benefits, … housing aid, tax exemptions, etc.”[17] Thus, the potential of Congress’s plenary power to both benefit and harm tribal interests is a source of ambiguity and conflict in the relationship between the United States and Indian nations.

5.3 Trust

1 The trust doctrine—also known as the trust relationship—is another legal principle that sometimes works to the benefit of Indian tribes but at other times interferes with tribal interests. The trust doctrine arises from the fact that “the majority of federal/Indian treaties … contained promises by the United States to protect tribes, to control and support their commercial activities, and sometimes to provide educational and medical care.”[18] Thus the U.S. government originally regarded Indian tribes not as genuinely sovereign nations on an equal footing with the United States but as domestic dependent nations needing U.S. protection.[19] Practically speaking, this was usually not an unreasonable assessment of the desperate needs of Indian tribes after conflict with the United States had deprived them of their traditional land bases and completely destroyed their means of subsistence.

2 However, today the federal government too often continues to exercise its trust responsibility in outdated ways that frustrate the desires of tribal nations “to exercise political, economic, and cultural self-determination.”[20] When the federal government makes decisions for tribal nations as if the “feds” know best, it perpetuates centuries old racist and ethnocentric ideas of Indigenous peoples as incapable of discerning their own best interests, and of course, it offends the dignity of tribal nations. And to make matters worse, the federal government doesn’t always faithfully or competently carry out its obligations to protect tribal interests. For example, in the 19th century, when the desires of White settlers came into conflict with tribal interests, the government often privileged White settlers’ desires. Even today, when the interests of powerful third-party interests, such as those of corporations or even those of the U.S. government itself, come into conflict with tribal interests, the interests of tribal nations are often disregarded.

5.4 Diminished Sovereignty

1 The third fundamental principle of Indian law—which is closely related to the first two discussed above—is the principle of diminished tribal sovereignty. This principle, or theory, like the other two, also flows from the Doctrine of Discovery. It is the idea that all real property rights and tribal sovereign rights were automatically and immediately limited when Europeans or Americans first “discovered” Native territories. The U.S. Supreme Court has even grounded some of its decisions in this theory.[21] It isn’t difficult to imagine the harm that diminished sovereignty has done and has the potential to continue doing to tribal dignity and the desires of Indian peoples for self-determination.

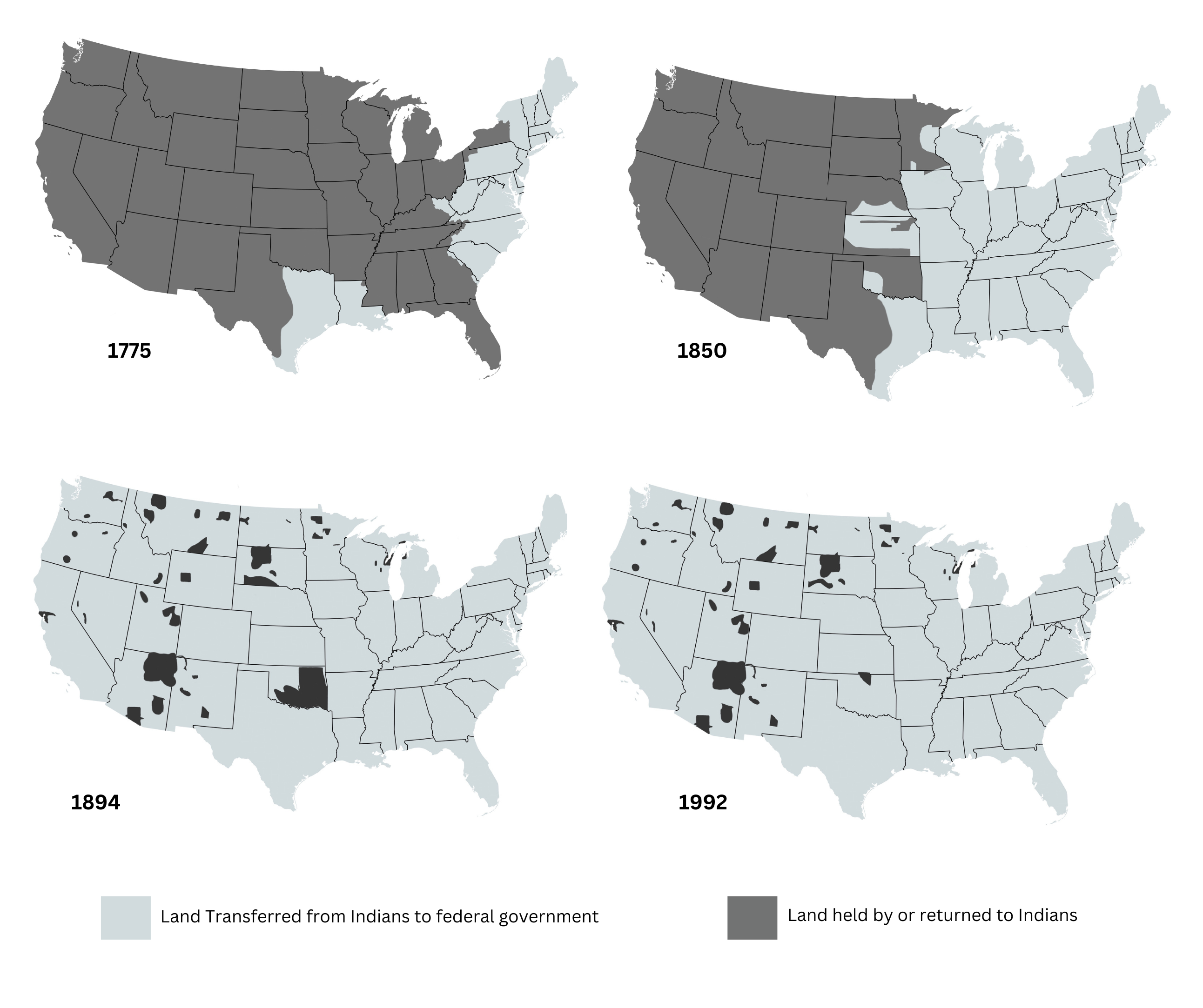

2 Historically, the United States pretended to deal with Indians in ways that had an appearance of legality, for instance by negotiating treaties and buying lands from various Indian tribes, but such treaties were often negotiated when Indian peoples were under duress and had little choice but to agree to bad deals. In some cases, they were virtually forced to sign treaties or face violent reprisals. Map 1.1 is a dramatic illustration of the results. The areas in white represent the lands transferred from Indians to the federal government between 1775 and 1992. The areas in dark represent lands held by Indians or returned to them. Today, tribal lands in the continental United States (including Alaska) only constitute 100 million acres, or 4% of the land.[22] This is roughly the size of the state of California.

6. Resisting Settler Colonialism

1 No one with a sense of social justice can study the history of Indigenous America without feeling anger, outrage, righteous indignation, and sadness. Most non-Indians are never exposed to a full recounting of the injustices that Indigenous peoples have endured as a result of U.S. settler colonialism. Usually, these injustices are merely hinted at as if they were simply the unfortunate errors of a less enlightened past, best forgotten and largely overcome today. But the past is rarely ever past, and the descendants of Indigenous peoples continue to live with the consequences of the U.S. settler colonial regime established even before the nation’s founding and then maintained ever since. Although we cannot provide the detailed account that this subject deserves, many excellent histories are available; (see Suggestions for Further Reading at the end of the chapter.) Nevertheless, we would be remiss if we did not at least give a brief outline of that shameful history.

6.1 Dispossession and Removal

1 Anglo-European migration to the lands of North America that would eventually become the United States began in the early 17th century as just a trickle, but by the early 19th century, it had grown into a mighty torrent. When the English began establishing colonies on the Atlantic Coast of North America, the entire Indigenous population north of present-day Mexico was perhaps only about five million. This population was widely distributed, of course, even if it was more heavily concentrated in the Eastern regions of the continent and along the Pacific Coast. During the 1600s, the first predominantly English settlers along the Atlantic coast were greatly outnumbered, but not for long. By the time of the first U.S. Census in 1790, shortly after the American Revolution, the non-Indian population had already reached about four million, and twenty years after that, it was over seven million.

2 In the meantime, the Indian population had decreased dramatically. Indigenous depopulation had several causes. For one thing, European and African diseases spread through Indigenous communities, diseases against which Indigenous peoples had developed no natural immunity. But the violence of colonialism is often underestimated. Indeed, settler colonialism seriously undermined the ecological and economic basis of Indian life, greatly exacerbating the effects of disease on the Native population.[23]

3 From the founding of the first successful English colonies, settlers continually put pressure on Indigenous people to make room for newcomers. At first, Native people accommodated new settlers, sometimes willingly and at other times more reluctantly. Native communities even tried, at times, to incorporate the newcomers into existing political systems. They tried to form alliances with settler groups, often as the way, for example, to gain an advantage over rival Native communities. However, Native people soon found that the settlers’ desire for land was insatiable. As waves and waves of European migrants arrived decade after decade, always demanding more and more land and resources, Native people began to push back. In the early colonial period, Indigenous nations exploited the conflicts between rival European nations. For example, as the American Revolution was in the making, some tribes aligned themselves with the British against the settlers because they considered the settlers a greater threat to tribal sovereignty.

4 American history textbooks in the United States generally present the outcome of the American Revolution as something to celebrate, which of course it was for the nation’s founders, but for Indigenous people, it was a disaster. The British presence in the American colonies had helped hold settler colonial expansion in partial check by prohibiting settling in the territories west of the Appalachian Mountains. With the British out of the way, the new U.S. republic launched an all out campaign to remove Indigenous people from the frontiers of eastern colonial America that non-Indigenous settlers desired for themselves. With the benefit of an ever more secure land base in the East and a professional Army, as well as an array of civilian militias and rangers, the United States engaged in a strategy of total war. Frontier rangers conducted search and destroy missions, burning down Native villages, destroying crops, and indiscriminately killing women and children or enslaving them. And Native people often retaliated in kind.

5 When war became too costly or too inconvenient for the U.S. government, leaders in Washington sometimes turned to treaties to try to accomplish through diplomacy that which proved difficult to achieve by means of war. The government proposed treaties in order to acquire land by paying various Indigenous nations to give up their claims to particular tracts of land. And they made agreements with Indigenous nations to establish borders between settler lands and Native lands, which the United States solemnly promised to uphold, sometimes in sweeping language, using words like “forever,” or “as long as the grass shall grow.” Too often Native people found that treaties were not honored, and some Native leaders refused to engage in treaty-making. But often Native people had little choice but to agree if they wished to survive.

6 By the early 1800s, Native people had already been resisting settler colonialism for two hundred years. They had suffered much loss but had developed cultures of resistance. They had made “accommodations to the colonizing social order, including absorbing Christianity into already existing religious practices, using the colonizer’s language, intermarrying with settlers and … with other oppressed groups, such as escaped African slaves.”[24] However, in spite of the accommodations of many Eastern Native nations, the general sentiment among Whites was that Indians were not wanted among them and had best leave or be removed.

7 Removal involved the large-scale migration of indigenous people from lands that they previously occupied, often after they had already made concessions to accommodate colonial populations and had moved from ancestral lands to settle in new places. The story of Indian removal is a long one. Numerous Native communities in every part of the continent from the Atlantic coast to California faced it throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Sometimes Native communities moved voluntarily, even if reluctantly, just to get away from troublesome Whites. But history is also replete with stories of forced removal, the most widely known of which was a series of forced relocations between 1830 and 1850 of 60,000 Cherokee, Muscogee, Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw from the Southeast to areas west of the Mississippi River. The forced relocations carried out by the government after the passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830 resulted in the death of thousands of Native people and is known as the Trail of Tears.

8 By 1850, the United States had expanded westward to the Mississippi River, and the eastern half of the country was firmly under settler-colonial control. The West had been designated as Indian Country by this time, and many Eastern Indian nations had been relocated there, yet White settlers were now coming for the lands west of the Mississippi. To the Indigenous nations of the West, White people were not strangers. White traders had been coming into the West to trade with the Native inhabitants for at least fifty years. But the relentless intrusion of White settlers into Native lands in the West was particularly exacerbated by the discovery in 1849 of gold in California. Pioneers poured across the Plains, intruding on the lives of Native people, bringing disease, alcohol, and violence. In 1851, Congress sought to guarantee the safe passage of settlers through Indian country by passing the Indian Appropriations Act, which formally established a Reservation system designed to confine various tribes to specific, strictly delimited, lands from which they were not to stray.

9 The various Indigenous nations of the Great Plains, Rocky Mountains, and Desert Southwest did not submit easily to such settler colonial domination. After 1865, soldiers, battle-hardened in the American Civil War and armed with advanced weaponry, now came west to subdue the “hostile tribes.” But Native fighters were formidable, and the U.S. Army in the West lost many battles. The most famous military defeat is surely the annihilation of George Armstrong Custer at the Battle of Little Big Horn.

10 The U.S. Army often responded to their humiliating defeats by launching attacks on Native villages and indiscriminately killing women, children, and elders. The so-called “Indian Wars” lasted for more than fifty years. The “Sioux Wars” and the “Apache Wars” are perhaps the most dramatic examples of the long-running resistance of Western Indian nations to U.S. domination. Some skirmishes in the Southwest persisted even into the early 20th century, but for the most part, the dispossession of Indian lands was complete by about 1890. In the end, Indigenous people were unable to withstand the sheer force of numbers and overwhelming abundance of military resources that the United States was able to throw at them.

6.2 Land Theft and Cultural Erasure

6.2.1 Indian Appropriations Act of 1871

1 While Congress passed multiple Indian Appropriation Acts over the years, the purpose of these acts had always been to provide money for the government to carry out its treaty obligations with various Indian nations. However, the Indian Appropriations Act of 1871 was a different matter. This one had a rider attached to it that officially declared the end of the U.S. Government’s policy of treaty-making. It read:

No Indian nation or tribe within the territory of the United States shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation, tribe, or power with whom the United States may contract by treaty; but no obligation of any treaty lawfully made and ratified with any such Indian nation or tribe prior to March 3, 1871, shall be hereby invalidated or impaired.[25]

2 This was a direct assault on the notion of Indigenous nations as sovereign and a step towards the denial of Indigenous claims to the legal right of self-determination.

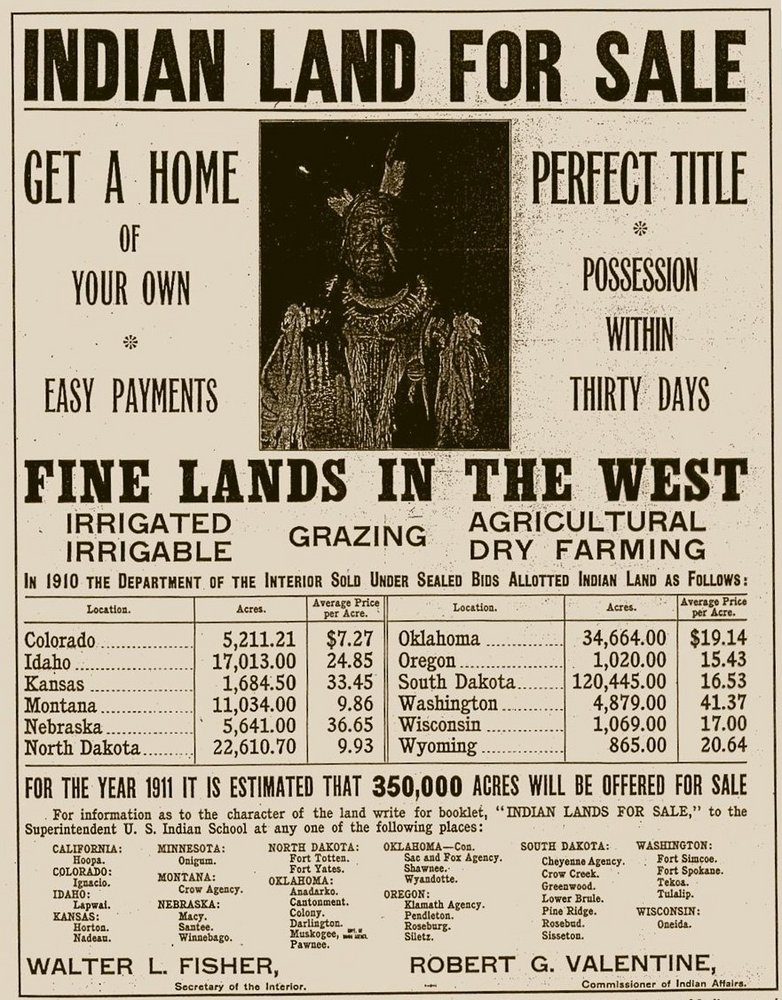

6.2.2 General Allotment (aka Dawes) Act

1 Throughout the 1880s, the United States enacted many laws and policies aimed at coercing Indians to give up Indigenous ways of life and adopt those of the White settlers. Among the most damaging to the cultural integrity of Indigenous people was the General Allotment Act of 1887. Driven by the belief that the primary obstacle to the “civilizing” of Native peoples was their communal use of tribal lands, the U.S. government in an effort to promote the ideology of “private property” began trying to break up reservations by distributing individual plots of land to individual Indians. Heads of households got 160 acres, while single persons over eighteen got 80 acres, and those under eighteen got 40 acres. Allotted land would not be owned outright, however; it would be held in trust by the government. And land left over after allotment to tribal members was declared “surplus” and sold to non-Indians. In this way, tribal holdings dwindled to a fraction of their former areas. But the consequences of allotment were not just material. Allotment had cultural ramifications as well. Recipients of allotments were required to adopt a Euro-American farming life,[26] thus allotment also served to undermine Native cultures.

2 Another unfortunate consequence of the allotment era was how the “discourse of blood” worked its way into U.S. government thinking and policy about “who was deserving of status as Native American” and how it “operated as a set of ideas about human nature that were powerful and intuitive”[27] and that had the covert effect of reducing the Indian population by defining people of mixed-descent as other than Indian. To understand how this worked, we need to discuss at greater length the meaning of “discourse of blood.”

3 Discourse of blood refers to a way of characterizing Indian identity in biological/racial terms. Central to the discourse (or way of talking about race) was the notion of blood quantum, which is a folk concept for defining the racial heritage of a person by calculating the fraction of inheritance attributable to various ancestors. It was thought that a parent with no mixed heritage constituted what was known as a “full-blood,” so if, for example, a “full-blood” Indian woman were to have a child fathered by a “full-blood” White man (or vice versa), the child would be half Indian and half White, or in other words a “half-blood.” Or to give another example, if a half-blood Indian woman and a White man were to have a child, the child would be 1/4 Indian. (In other words, one of the child’s four grandparents would be a “full-blood” Indian.)

4 But let’s do a little thought experiment. Let us suppose the child’s White father has abandoned the family, and the child’s “half-blood” Indian mother lives with her (less than “half-blood” or “mixed-blood”) child in the community of the “full-blood” Indian grandparent (let’s suppose it is a grandmother). The child grows up immersed in the Native community—let’s say Anishinaabe—speaks the Anishinaabe language, practices Anishinaabe customs and traditions, and identifies as Anishinaabe. Is she Anishinaabe? Or is she White? Framed in this way, the question seems absurd to us, and so it seemed to many Native people when the discourse of blood first crept into Indian policy after the period of allotment was already well underway.

5 Indeed, Jill Doerfler, a professor of American Indian Studies who grew up on the White Earth reservations has argued, that as far back as the mid-1800s,

… memories recounted in the oral testimonies of the White Earth Anishinaabeg … demonstrate that White Earth Anishinaabeg did not use blood as a metaphor for ancestral/racial ancestry; to them, this association was illogical and senseless. In their understanding, the meanings of the terms “full-blood” and “mixed-blood” were not bound to notions of ancestry but were flexible terms generally tied to a variety of lifestyle choices, such as clothing and religious affiliation, as well as economic conditions.[28]

In other words, the Anishinaabeg regarded identity as more a matter of culture than of biology.

6 Similarly, the Five Tribes that had been relocated to Oklahoma after the Indian Removal Act, in particular the Cherokee, interpreted “blood” in terms of cultural orientation and upbringing rather than of ancestry.[29] In fact, when the General Allotment Act first went into effect in 1887, even the U.S. government paid very little attention to supposed racial classification in determining eligibility for allotment. All that was required for allotment was for a recipient to be recognized by a tribal nation as a member.[30]

7 By the middle of the 1890s, however, many non-Indians who had flooded into Indian territory after the Civil War had managed to get themselves, fraudulently, onto tribal rolls among the Five Tribes in order to take advantage of allotment. Yet rather than working with the Five Tribes to remove the intruders, the government began instead to promote a trope that portrayed mixed-descent people, who actually were eligible for allotment under tribal laws and practices, as if they were a problem. Characterized as shrewd, manipulative, corrupt, and undeserving, government officials often took it upon themselves to declare mixed-descent people as ineligible for tribal citizenship. As a result, many mixed-descent people ended up being unjustly dispossessed.[31]

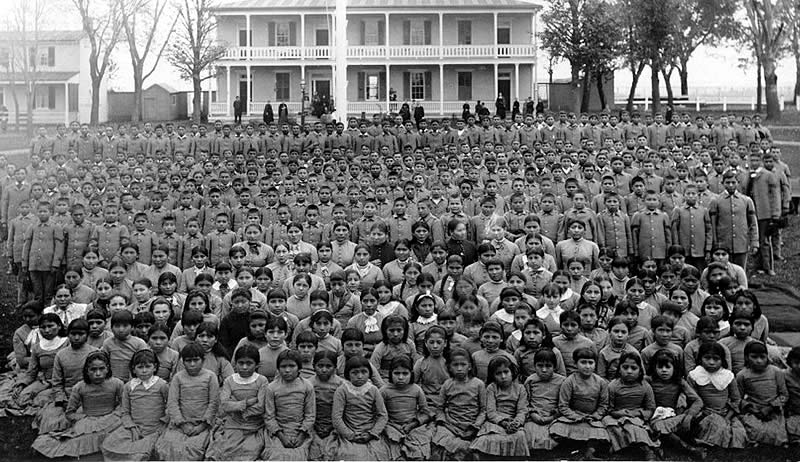

6.2.3 Indian Boarding Schools

1 An even more insidious attempt to erase Native culture involved the establishment of boarding schools. The first boarding school, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, was established in Pennsylvania in 1879 by Richard Henry Pratt, a Civil War veteran and a veteran of the Indian Wars. In 1875, Pratt had been given the task of interviewing Indian combatants after their capture to determine how they should be charged. “Somehow his sympathies were engaged, and he tried to clear as many of them as possible.” But since the combatants were deemed too dangerous to return to their tribes and homelands, Pratt was then tasked with escorting them to prison at Fort Marion, Florida where Platt began experimenting with Indian education, hiring teachers to instruct them in English, art, and mechanical studies.” Impressed by “the Indians’ aptitude for ‘civilization,'” as Pratt put it, he would eventually lobby Congress for funds to set up a school dedicated to “the civilization of American Indians.”[32]

2 Pratt was open-minded, even radical for his time, believing that all human beings, given equal opportunities, would have equal capacities. Nevertheless, he was still caught up in the White-supremacist ideology that could see no redeeming value in Native culture. Reflecting on his mission, Pratt once opined:

A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one … In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.[33]

3 After the establishment of Carlisle, dozens of other boarding schools sprang up across the country. Some parents, believing that assimilation was inevitable, saw the boarding schools as opportunities to enable their children to adapt successfully to the realities of life in a world dominated by Whites, and they sent their children willingly. But too often parents were coerced against their better judgement into participating in the boarding school system.

4 Although not every Indian who attended a boarding school has condemned the experience, the system is notorious for its cruelty and abuse. From the moment children arrived at boarding school, they were systematically robbed of their cultural identities from the hair on their heads to the clothes they wore and even the languages they spoke and the religions they practiced. For instance, children were prohibited from speaking their native languages and a typical punishment for anyone caught doing so was to have their mouth washed out with soap. Beatings, confinement with only bread and water for rations, denial of comfort and medical care when ill, and sexual abuse were not uncommon.[34] Generations of Native children were thus brutalized and traumatized, leaving them cut off from their families and their heritage and stripped of self-esteem, angry and often broken for life.

5 But none of what has been said above should be taken to mean that Native peoples accepted their circumstances passively. From the origins of settler-colonialism on, tribes and individuals engaged in resistance and negotiation with the policies that were imposed upon them.

6.2.4 Indian Reorganization Act

1 By the 1920s, the strategies of allotment and forced assimilation had come to be seen as failed policies. As a general mood of progressive political and popular thought took hold in the U.S., policymakers began to rethink federal Indian policy. When President Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in 1933, he appointed John Collier as Commissioner of Indian Affairs. The progressive minded Collier rejected the policies of forced assimilation that had characterized federal Indian policy for much of its history. He was particularly critical of the Indian Boarding School system and soon advanced three educational reforms:

(1) the substitution of community day schools and local public schools for boarding schools; (2) the replacement of a curriculum that suppressed Indian culture with one that promoted it; and (3) the adoption of vocational programs that served the immediate needs of the Indian communities.[35]

2 Collier also worked with Congress to pass The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934. Also known as the “Indian New Deal,” the IRA represented a significant reversal of federal policy. Indeed, David E. Wilkins, a member of the Lumbee Nation and prominent specialist in federal Indian law, has characterized the IRA as “a legitimate but inadequate effort on the part of Congress to protect, preserve, and support tribal art, culture, and public and social organization.” It sought to restore to Native peoples “some measure of tribal self-rule,”[36] towards which all previous federal Indian policy had been hostile.

3 While its ultimate aim continued to be the gradual assimilation of Indians into American society, the IRA put an end to the infamous allotment policy with its steady erosion of Indian homelands. It also created processes for recovering some of the lands already lost and “devised structures by which new lands could be incorporated.”[37] It even paved the way for tribes to establish their own tribal governments, which many tribes did. On the downside, it placed limits on the forms that tribal governments could take, privileging constitutions, charters, and by-laws that closely resembled U.S. state and local governments. Moreover, the structuring of tribal governments remained subject to the approval of the federal government.[38] Another unfortunate consequence of the Indian Reorganization Act was its failure to disavow the discourse of blood that had seeped into Indian policy during the earlier period of General Allotment. In fact, the discourse of blood continued to be pervasive as one tool of the Indian New Deal.[39]

4 But in spite of its shortcomings, the Indian Reorganization Act was a philosophically radical departure from the previous era of assimilation and brought with it the possibility of redressing past wrongs and honoring the desires of many Native nations for self-determination. At the same time, it failed to rid government policy of certain established ideas about “blood,” people of mixed descent, and authentic Indian culture with divisive consequences for mixed-descent people that still persist today.[40]

6.3 Termination and Relocation

6.3.1 Termination

1 By the 1940s, the winds that had been blowing in the direction of greater respect for Native cultures and greater latitude for self-government all began blowing in exactly the opposite direction. After John Collier’s tenure as Commissioner of Indian Affairs ended, Indian policy came to be dominated once again by men with assimilationist prejudices. The assimilationists’ basic argument was that Indians had already become assimilated enough to handle their own affairs and no longer needed government services. It was time for Indians to stand on their own feet as “equal” citizens and integrate with mainstream society. Even some Native Americans believed that they would be better off free of federal oversight.[41]

2 Throughout the 1940s, the assimilationists, Native American as well as White, largely disregarded the expressed needs and the protests against assimilation of more traditional-minded Indians. Meanwhile Congress chipped away at the trust relationship that had existed between the U.S. government and Native people since the beginning of treaty-making. Finally, in 1953, the Termination Act (House Resolution No. 108) was signed into law.[42] Its ultimate goal was to eventually end the federal-Indian trust relationship once and for all and quickly assimilate Indians into American society.[43]

3 Although termination would not be immediate for every tribe, policymakers established a set of guidelines designed to eventually accomplish the objective of terminating every tribe.[44] In other words, Native groups would all lose whatever original status they had enjoyed as sovereign nations, including whatever protections that had afforded them. However, as termination proceeded, it soon became clear that it was nothing more than another in a long list of attempts by the U.S. government, not just to separate Native people from communal lands, but to do away with Native people themselves.[45]

4 Fortunately, the process of termination took so long that the tribes who were scheduled for it later had an opportunity to see what a disaster termination had been for the Menominee, who had been the first to experience it. Some tribes fought the government’s efforts to terminate them. The Menominee themselves, after agreeing to termination, spent years fighting for restitution and eventually got their reservation back. But the era of forced termination lasted for almost twenty years before it was finally ended in 1970, although some tribes are still fighting to undo the damages they suffered from it.[46]

6.3.2 Relocation

1 In the 1940s, the vast majority of Indians lived on reservations. Only 6% lived in cities compared with 56% of other Americans. However, by 1970, half of all Indians lived in cities.[47] This huge demographic shift is often associated with termination and the federal relocation programs that accompanied it throughout the 1950s, 60s, and early 70s.[48] (See for example, the Indian Relocation Act of 1956.) But for some Native people, migration away from reservations began well before termination. Of course, Indian boarding schools had taken Indians away from the reservation since the late 1800s. But World War II played a big role in the mid-20th century. When the United States entered the war, many American Indians enlisted in the military. Overall, about 25,000 Indians served in the armed forces during the war, a proportionately higher percentage than any other ethnic minority. Moreover, roughly fifty thousand Indian men and women left the reservation to work in aircraft factories, in other war industries, and on the railroads.[49]

2 When World War II ended, military veterans, in particular, unable to find work on or near reservations, or simply unable after the war to readjust to life on the reservation, often moved to cities in search of jobs. The younger generation, too, curious about city life, sometimes left the reservation for the city.[50] So voluntary relocation was not a completely new experience for Native people. However, beginning in the 1950s, the federal government began aggressively promoting relocation, ostensibly as a means of raising the living standards of Native people. Of course, the government was also keen to separate as many Native people from reservation life as possible in furtherance of its termination scheme and as a way of cutting services to reservation Indians. As a result, relocation became a more ubiquitous experience for many Native people.

3 Among the first urban centers to receive relocated Indians in the 1950s were Denver, Salt Lake City, Los Angeles, Cleveland, San Francisco, St. Louis, San Jose, Seattle, Tulsa, and Minneapolis.[51] Some Native people were unprepared for urban life and the challenges of adapting away from their reservations, and many accounts highlight the dire circumstances they faced. Urban Indians often felt “abandoned by a paternalistic federal government that raised expectations for a better standard of living” that never materialized;[52] however, relocation was not always a disaster. As David Treuer has written:

… relocation wasn’t necessarily a one-way street: Indians moved to the city and moved back to the reservation, or their children did. And while they were in cities they mixed not only with other races but with other tribes as well. … the old tribal warfare, and the intertribal bigotry that marked tribal relations in the nineteenth century, faded away as Indians from vastly different tribes found themselves living as neighbors in the city. They found they had much more in common with one another: a shared historical experience if not shared cultures, the same class values, the same struggles. Networks among tribes—forged through marriage, school, city living, and service in the armed forces—were strengthened from 1940–1970.[53]

4 Or as Douglas Miller has emphasized, relocation was not simple a case of an entire generation of Native people being duped by the White man. Rather, Native people recognized the opportunities that relocation provided to “transcend physical and cultural boundaries of the reservation and a resolutely second-class citizenship.” They “weighed the potential consequences and made bold decisions about their futures.”[54] According to Miller, the prevailing narrative that Native people were always helplessly shuffled to locations of the government’s choosing does not accurately reflect the facts. Native people made relocation work on their own terms, often negotiating their own opportunities, coming and going wherever and whenever they pleased.[55]

5 By the 1960s, half of the American Indian population lived in cities and towns, but they were in close and constant contact with the other half still living on reservations. Moreover, “Indians were growing in numbers and strength. … [and] the civil rights movement that was beginning to rock the country had a counterpart that rocked Indian communities and would grow, by the 1970s, to capture the attention of the entire country.”[56]

7. Indigenous Revival

7.1 From Termination to Self-Determination

1 By the mid-1960s, President Lyndon Johnson’s administration had recognized what a dismal failure termination had been for the economic and political welfare of Native people. In 1964, having declared “War on Poverty,” Johnson signed the Economic Opportunity Act and established the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) to administer the local distribution of funds to alleviate poverty wherever it might be found. There was plenty of poverty on Indian reservations and among Indians in general, and the Economic Opportunity Act would become a direct benefit to Indian tribes.

2 Indeed, the Great Society programs launched during the Johnson administration were major innovations in federal-Indian policy. For instance, for the first time in U.S. history, Indian tribal governments were recognized by federal agencies as legitimate governments and granted federal funds on a government-to-government basis, just as other U.S. state and local governments were. This meant that tribal governments would no longer be dependent for money upon bureaucrats in the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). As Philip Deloria has observed,

Tribes could, to some degree, set their own priorities. They could hire, supervise, and fire people on their own. They had telephones and copying machines to spread information throughout Indian country and the money to hold conferences to organize for the common good. They could go to Washington whenever they wanted to and not only when the superintendent or the central office of the BIA told them they could. These things altered the nature of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the relationship between tribes and the federal government. They changed the face of Indian affairs in a way that will never completely be reversed.[57]

3 According to David Treuer, “The OEO was the beginning of the end of the top-down control that had been exercised on Indian people from the beginning of contact with White people.”[58] Although the OEO itself did not survive the presidency of Ronald Reagan, the policy of “self-determination without termination” has remained intact since it was first announced by President Richard Nixon in 1970.[59]

4 The U.S. government’s commitment to Native American self-determination received further reinforcement with the passage in 1972 of the Indian Education Act, which provided funding to improve education for Native communities and provided the means for Native people to exercise greater control over their schools. The law directed local educational agencies receiving funding to “use the best available talents, including people from the Indian community” and to develop programs that “build upon and support the heritage, traditions and lifestyle of the community being served,” and to do so “in open consultation with Indian parents, teachers, and where applicable, secondary school students.”[60]

5 The Indian Education Act was not without its problems, but it was a radical departure from the U.S. government’s efforts at cultural erasure and indoctrination during the Indian Boarding School era. Indeed, decade after decade and in spite of changes in presidential administrations, budget cuts, and inadequate funding, Native people made significant progress in gaining greater control over their educational needs. By the 1980s, most high schools in Indian country had Indian education programs, with a dedicated staff of Indian counselors to advise students on everything from drug and alcohol addiction to college scholarships. Some schools offered instruction in tribal languages, history, and culture. In the 1980s, many tribes also began establishing tribal colleges.[61] “By 2017, there were thirty-seven tribally controlled colleges and universities and 130 schools operated by Indian tribes and tribal organizations and funded by the Bureau of Indian Education.”[62]

7.2 The Rise of Red Power

1 During the 1960s and 1970s, U.S. government policies towards Native people still left much to be desired, but they were undeniably more enlightened, historically speaking, than federal Indian policy had ever been before, and they undoubtedly helped put Native people on the road to self-determination. But federal government policies alone were not responsible for the strides that Indians would make in the second half of the 20th century. As David Treuer points out, “change was coming from within Indian communities, too.”[63] Indeed, many of the changes in government policy were the result of Native activism.

2 While Indians created many different organizations in pursuit of their interests throughout the 20th century, three organizations that emerged in the middle decades of the century are particularly significant for understanding the reawakening of Indian pride and the collective determination on the part of Indians to reclaim their heritage and culture.

3 These three organizations—the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), the National Indian Youth Council (NIYC), and the American Indian Movement (AIM)—all shared the same objectives although the differed radically in tactics. Moreover, their vision of what Native peoples could and should be was markedly different from that of the prominent Indian leaders born a generation or more earlier. For example, as Bradely Shreve has pointed out, the first Indian-controlled intertribal organization founded in 1911—the Society of American Indians (SAI)—embraced the ideals of “assimilation, self-help, and social justice.”[64] As Shreve has put it:

… the founding members [of the SAI] believed that Native people needed to move away from the past, reject tradition and custom, and embrace currents of “modern civilization.” … They rejected notions of racial superiority or inferiority but believed that “natural laws of social evolution’ placed Native people below Europeans. Only through hard work, individual initiative, citizenship, and perseverance could the Indian advance up the hierarchical ladder.[65]

4 The New Indians,[66] as Stan Steiner called them in a book that first brought public attention to the Red Power Movement, did not agree with the SAI’s assessment of the problems that Indians faced in the 20th century. Rejecting the old so-called “progressive era” ideologies of assimilation and acculturation, the new Indians advocated instead: cultural preservation, enforcement of treaty rights, self-determination, and tribal sovereignty.

7.2.1 National Congress of American Indians

1 The oldest of the three organizations, and the one perhaps best seen as a precursor of the Red Power Movement, was the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), founded in 1944. The inaugural convention in Denver drew close to eighty delegates representing more than fifty tribes from twenty-seven states, and by the second convention in 1945, NCAI membership had grown to over three hundred members.[67]

2 When it was first founded, the NCAI’s primary mission was to combat the termination policies of the assimilation advocates in Congress. To this end, the NCAI adopted a platform advocating tribal sovereignty, territorial integrity, and the honoring of treaty rights, and went to work lobbying lawmakers and pursuing lawsuits.[68] The NCAI also worked to remedy violations of civil rights and the failure of the Indian Claims Commission to award just compensation to Native victims of fraudulent land deals and mismanagement of Native people’s trust funds. The NCAI was more successful on the civil rights front, helping to overturn discriminatory laws in Arizona and New Mexico that prevented Indians from voting. It was less successful, however, in its battles with the Indian Claims Commission.[69]

3 As it continued its work throughout the 1950s and into the ’60s and ’70s, the NCAI achieved many significant victories, among them—overcoming federal job discrimination against Indians, preventing language in the founding documents for Alaskan statehood that would have banned reservations, limiting the ability of states to exercise jurisdiction over Indian civil and criminal cases, and addressing “in a consistent and effective manner broad issues of health care, employment, and education.”[70]

4 In the early years, the NCAI was led by men and women most of whom had been born in the late 1800s or early 1900s, and while they were not as conservative as their predecessors in the Society of American Indians, the NCAI would soon be considered too conservative for a younger generation coming of age in the late 1950s and early ‘60s.

7.2.2 National Indian Youth Council

1 The founders of the National Indian Youth Council (NYIC) came on the scene when liberation movements against colonial oppression were popping up all over the world and the civil rights movement was gaining momentum in the United States. Most were college students who had grown up on reservations and in rural tribal communities.[71] Although the NIYC would adopt the same basic mission as the NCAI, namely to “preserve Native culture, uphold treaty rights, push for self-determination and promote tribal sovereignty,” its members tended to be impatient with the slow pace of change brought about by the NCAI’s approach to Indian issues. Where the NCAI maintained a strict policy of working entirely within the political and legal system and avoiding organized protests and direct action, the NIYC believed that “there comes a time when we must take action.”[72]

2 Before the founding of the NIYC, many of its members had participated in a variety of formative experiences. For instance, as college students, they had created on-campus Indian organizations which in turn spawned the Regional Indian Youth Council (RIYC), first in New Mexico and eventually in other states across the West. Some future NIYC leaders had even been officers in these regional organizations. By the end of the 1950s, the RIYC had brought hundreds of young women and men together in intertribal fellowship where they could discuss pertinent issues of the day, such as education, assimilation, language retention, and religion. In the process, participants also learned principles of political organization and even parliamentary procedure.[73]

3 Many future NIYC leaders had also participated in summer workshops hosted at the University of Chicago by anthropologists who were sympathetic to Indian issues. These six-week intensive courses brought together students from all over Indian country to learn about colonialism, racism, cultural and social theory, nationalism and the like. The workshops helped Indian youth understand the psychological effects of colonization on Native Americans and recover a sense of pride in their tribal cultures and heritage.[74]

4 In 1961, a group of young activists from diverse tribes, who had become acquainted through their participation in many of the organizations and events discussed above, found themselves at the American Indian Chicago Conference (AICC). Attended by some eight hundred Indians from over ninety band and tribes, for the purpose of establishing policy goals for the new Kennedy administration, the 1961 Chicago Conference was “the largest, most diverse intertribal gathering ever recorded up to that time.”[75] However, because the conference organizers had made no provisions for college students to participate in the conference proceedings, the students convened their own youth caucus and formed the nucleus of what would soon become the National Indian Youth Council. Frustrated with many in the older generation that they felt had bought into an assimilationist agenda, or were otherwise too cautious in their fight for Native self-determination, the NIYC leaders hoped to chart a more aggressive course.[76]

5 Inspired by what they saw happening in Black America where young people were directly challenging the status quo in the South by deliberately violating Jim Crow laws, the NIYC sought opportunities to directly attack the status quo in Indian country. One of the most well-known direct-action campaigns that the NIYC became involved in was the fight to force the state of Washington to honor treaties that had been signed more than one hundred years earlier. In particular, several treaties from the 1850s had granted various tribes in the Pacific Northwest the right to continue fishing and hunting according to traditional patterns. The tribes had even given up millions of acres of land in exchange for guaranteed fishing and hunting rights. Nevertheless, the state of Washington had a history of regulating commercial and sport fishing, and they had long sought to apply the same regulations to the local tribes in violation of the relevant treaties. According to Shreve, the Red Power Movement began in earnest when Native students first launched an organized “fish-in” movement in 1964 to protest these treaty violations.[77]

6 Fish-ins involved the deliberate violation by Native people of the state’s fishing restrictions. However, because the state did not readily buckle under the Indians’ direct-action campaign, the fish-in movement turned into a decade-long struggle, punctuated by arrests, episodes of violence, and numerous court cases. Over the years, some court rulings had been favorable to the Native cause, but many others had not. Eventually, in 1974, the Northwest Indians and Native activists finally prevailed in U.S. district court when the federal government supported Native claims against the state of Washington. In the United States v. Washington, Judge George Boldt ruled that “treaty Indians had the right to catch 50 percent of Washington’s harvestable fish.” Unfortunately, the Attorney General of Washington state refused to enforce the decision and appealed it to the Supreme Court. Ultimately, the Supreme Court in 1979 upheld Boldt’s decision and closed the case to further review.[78]

7 By that time, the NIYC was no longer directly involved in the fish-in movement, but their success in mobilizing intertribal cooperation and their savvy use of the media ten years earlier had “put the battle over fishing rights on the political map.” As Shreve has noted:

Their efforts stood as the first instance of united intertribal direct action, and they encouraged subsequent Indian activists to use civil disobedience and mass protests as a means to make changes in Indian policy. In the late 1960s and 1970s, many urban-based organizations followed the lead of the NIYC activists.[79]

7.2.3 American Indian Movement

1 Whereas the NCAI and the NIYC sprang up largely among Indians living in rural and reservation communities, the American Indian Movement (AIM) was primarily an urban-based movement. As mentioned earlier in the chapter, by 1970, as a result of the U.S. government’s post-World War II relocation programs, there were just as many Indians living in urban settings as there were living on reservations, so the rise of an urban Indian movement is hardly a surprise.

2 AIM was first founded in 1968 by a group of Ojibwes living in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The conditions that led to the establishment of AIM were similar to those that had led to the establishment of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in Oakland, California two years earlier. Fed up with police brutality in Black neighborhoods, the Black Panthers had done two things: 1) they had assumed their Second Amendment rights “to keep and bear arms,” and 2) they had begun following the police around, monitoring their activity. Just as the police in Oakland had a habit of harassing Blacks, the police in Minneapolis had a habit of harassing Indians, routinely raiding Indian bars and making mass arrests of Indians “for drunk and disorderly conduct.” Following the Black Panthers’ example, AIM began organizing self-defense patrols and monitoring police activity. Through confrontations with the police that sometimes turned violent and resulted in the arrests of AIM members, AIM succeeded in reducing the prevalence of such police raids.[80]

3 Moreover, like the Black Panthers, AIM established community service programs. As Shreve has noted:

AIM … gave urban Indians rides to work, distributed food to the needy, and raised money to help poor families. The organization worked to establish the Indian Health Board—the first urban Indian health care facility—and started the Little Earth Housing Project to improve living conditions. Perhaps most impressively, AIM founded the Heart of the Earth Survival School in Minneapolis and the Red School House in neighboring St. Paul.[81]

4 “By the 1970s there were about sixteen AIM survival schools in urban centers and reservation communities,” all founded by women, “among them Miniconjou activist Madonna Thunder Hawk and Ojibwe activist Patricia Bellanger.” The survival schools provided a welcome alternative for Native youth who in the public schools had long been subjected to discrimination and deprived of opportunities for an education that honored the heritage and values of their various tribal nations.[82]

5 Non-Indians, if they know anything at all about AIM, are likely to associate it with a number of dramatic events that commanded a lot of media attention at the time of their occurrences. First, we might mention the takeover of Alcatraz Island in the San Francisco Bay. Once a federal prison, Alcatraz had been abandoned in 1963. But in 1969, AIM joined forces with several other Native organizations, including the NIYC and a Bay area group, the United Native Americans to form a coalition that called themselves Indians of All Tribes (IAT). Under the leadership of LaNada Means (Shoshone-Bannock) and Richard Oakes (Mohawk), over eighty men and women managed to get themselves transported to Alcatraz where they then occupied it for nineteen months. Claiming that the land was rightfully Indigenous land, the occupiers demanded, among other things, that the island be turned into an Indian cultural center to replace the one in San Francisco that had recently burned down.[83]

6 The Alcatraz occupation lasted for nineteen months during which time AIM leaders engaged in negotiations with representatives both from the state of California and from the federal government, neither of which was successful. AIM’s ability to negotiate effectively was no doubt hindered by internal conflict among the leaders, but when Richard Oakes’ twelve-year-old daughter fell from one of the island’s structures and was killed, many of the occupiers lost heart. By the end of the occupation on June 11, 1971, the number of occupiers had dwindled to fifteen, and this small group was finally forcibly removed. In one sense, the occupation was a failure. No Indian cultural center was built; instead, the federal government transferred Alcatraz to the National Park Service, and it became part of the national park system. But according to Treuer, “[t]he episode had a deep and lasting impact … It caught the attention (and sympathy) of the Nixon administration and was hugely influential in Nixon’s decision to formally end the termination period. And it inspired AIM to bigger actions.”[84]

7 According to Nick Estes, after Alcatraz, AIM membership grew rapidly and “by 1973, there were seventy-nine chapters,” including “eight in Canada.” And as “the movement swept through Oceti Sakowin country, it adopted a specifically nationalist character,” making the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie a symbolic theme of their activism. “In 1970, AIM, United Native Americans, and Lakota activists from South Dakota occupied Mount Rushmore in the Black Hills to bring attention to the 1868 Treaty and the fact that the land upon which the monument had been built was stolen.”[85]

8 As time went on, AIM became increasingly militant, favoring “tactics of takeover and occupation” while also not shying away from inflammatory rhetoric and threats of violence as well as actual violence. In 1972, for example, AIM joined forces with NIYC and other activist groups in the Trail of Broken Treaties, a coast-to-coast caravan of thousands of Natives to BIA headquarters in Washington, D.C. where AIM leaders took over BIA offices. At the center of the organizers’ demands was a twenty-point proposal demanding, among other things, restoration and enforcement of treatymaking as a matter grounded in Constitutional authority. Such a restoration would force the federal government to recognize each Indigenous nation’s sovereignty.[86]

9 However, as often happened in events with prominent AIM presence, the takeover was chaotic and ill-planned, and before it was over, it devolved into violence and the sacking of the BIA building, “with little accomplished.”[87] Nevertheless, as Treuer has suggested, AIM “was showing Indians around the country that they were proud of being Indian,” and that “Indians from reservations and cities alike were, for the first time, pushing back against the acculturation machine that was part of America’s domestic imperial agenda, and doing it loud and proud.”[88] On the other hand, NIYC, which had always advocated non-violent direct action, had become increasingly unhappy with AIM’s readiness for violence, and the BIA takeover more or less marked the end of NIYC’s active alliance with AIM.[89]

* * *

10 Perhaps the most widely-remembered event of the early Red Power era was the 1973 AIM takeover of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation. Near the southwest corner of what is now South Dakota, Wounded Knee had been the site of a massacre in 1890 of at least 250 men, women, and children by the U.S. Seventh Cavalry and is typically regarded as marking the end of the Sioux Wars. The symbolic significance of Wounded Knee for Lakota people undoubtedly played a role in AIM’s decision to occupy it as a way of calling attention to the U.S. legacy of injustice towards Native people.

11 The so-called Second Wounded Knee incident had many precursors, but the main event arose when the more traditional Oglala Sioux of Pine Ridge sought to remove the increasingly authoritarian and corrupt tribal chairman, Dick Wilson. A “mixed-blood,” assimilated Lakota, Wilson had a reputation for favoring friends and family and discriminating against more traditional reservation residents.[90] Moreover, he had his own private paramilitary “GOON squad,” with which he terrorized his political opponents. Many in the community, especially elders and women, wanted to remove him and restore traditional tribal governance. When an effort to impeach him failed, the tribal leaders hoped to force him out with help from AIM. Unfortunately, Wilson also enjoyed the support of certain elements within the federal government, such as the FBI, which saw communist conspiracies lurking behind every liberation movement and had infiltrated civil rights groups and indigenous rights groups alike.[91]

12 With Wilson still in power and AIM members continuing to converge on Pine Ridge, the reservation became increasingly militarized with Wilson’s GOONs, U.S. marshals, Special Operations forces, and FBI agents. A tribal conference was convened in Calico to discuss the Dick Wilson problem, and upon the advice of spiritual leader Frank Fools Crow, AIM members left Calico, gathered at Wounded Knee and took it over. “Federal, state, and tribal law enforcement, already in Pine Ridge because of the political situations of the past year, blocked the roads and surrounded the village.” Although the strategy of the U.S. government was to wait the occupiers out rather than to mount an assault, AIM was determined not to give up. The situation turned into a 71-day siege, punctuated by demands on the part of AIM, failed negotiations, and frequent firefights, a few of which resulted in casualties.[92]

13 The siege of Wounded Knee got a lot of media attention until it became too dangerous for reporters to stay. The public was shocked to witness, in 1973, Native fighters, armed mainly with shotguns and hunting rifles, facing armored personnel carriers, helicopters, and federal troops armed with automatic weapons. The image was not a good one for the United States, especially considering the history of Wounded Knee, and many Americans were sympathetic to AIM. Towards the end of the standoff, several modest agreements were reached: “the Oglalas would have their grievances heard by the Whitehouse, and the Justice Department would investigate criminal activity on Pine Ridge,” but AIM leader and spokesman “Russell Means would turn himself in and face the charges against him.”[93]

14 In the end, it seemed there had been an awful lot of senseless violence for very few constructive results. Meanwhile, Dick Wilson maintained his grip on Pine Ridge and colluded with the FBI in a “dirty war” against his adversaries at Pine Ridge and a smear campaign against members of AIM. According to Nick Estes: “The dirty war that came after in Pine Ridge left forty-five unsolved homicides of AIM leaders and organizers,”[94] raising the suspicion that Wilson and the FBI may have resorted to targeted assassinations to try to crush the organization.

* * *

15 It is difficult to assess the legacy of AIM. It is certainly true, as Estes has observed, that “AIM has been blamed” not just “for the loss of life” during the 1973 Wounded Knee occupation but “for the murderous crackdown and the increased deprivations of Indigenous communities that followed.”[95] But to accept this at face value (which Estes does not) would be disingenuous. For what is also true is that murderous crackdowns, including discriminatory use of police violence and incarceration directed at Indigenous communities, as well as other groups, such as African Americans and Latinos, are endemic features of the U.S. justice system. We may think AIM’s tactics were extreme, but in effect, they revealed the extremes to which the U.S. has gone (and continues to go) to maintain the racial, ethnic, and economic status quo.

16 On the other hand, as David Treuer has observed: “Despite the destructive antics of its leadership, which hurt a great many people, Indians as well as non-Indians, … AIM did manage to make [positive] changes in Indian country, thanks mostly to its rank and file.” Some of AIM’s positive contributions to Indian communities have already been noted above. Others include: successfully advocating for Indian education in prisons (1978), and the creation of the Indian Opportunities Industrialization Center in Minneapolis, a job training program (1979).[96]

7.2.4 Native Women and Red Power

1 Often overlooked in telling the story of AIM, and indeed in the telling of many civil rights and liberation stories, is the role of women. In fact, after the Wounded Knee occupation, it was Native women who made many of the most constructive contributions to the Red Power movement. There is perhaps no more iconic example than Madonna Thunder Hawk. Present at Alcatraz and Wounded Knee, Thunder Hawk’s most important work came after the Wounded Knee occupation. According to Nick Estes:

She was central to organizing the Wounded Knee Legal Defense/Offense Committee, to combat the legal repression following the takeover; the We Will Remember Survival School, to provide an alternative education for Native youth; the International Indian Treaty Council, which advocates for the defense of Indigenous treaty rights at the United Nations; the Women of All Red Nations, organizing American Indian women around reproductive health, including against illegal sterilization and environmental contamination of Native lands; and the Black Hills Alliance, a Native and non-Native alliance formed to halt uranium mining in Black Hills.[97]

2 Thunder Hawk has continued right into the twenty-first century her tireless leadership and advocacy for Native peoples’ rights. For instance, she played a role in the establishment of the Lakota People’s Law Project, and she continues to fight against resistance from the state of South Dakota for the rights of Indian children to remain under Native kinship care in legal accordance with the Indian Child Welfare Act. In 2016, Thunder Hawk joined the movement against the Dakota Access Pipeline, camping at a protest on the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota. And more recently, she had a hand in the founding of the Women Warrior’s Project and participated in the documentary, Warrior Women, which highlights the contributions of Native women in the fight for social justice in Indigenous communities.

Chapter 1 Study Guide/Discussion Questions

Activity 1.1

After reading sections 1-5 of the chapter, discuss the following questions with one or more fellow readers.

-

- Evaluate the claim that Christopher Columbus discovered America.

- What is the most important thing to know about being a skillful communicator when speaking with an American Indian person about their identity?

- Why do Indian tribes often have at least two different names?

- What is a minority? In what sense do Native Americans fit the definition? Why does the writer say Native Americans are not “minorities?”

- Why does the writer say that the status of American Indians is extra-constitutional (outside of the Constitution)?

- What is the Doctrine of Discovery? Do you think the Doctrine of Discovery should have any place in American law? Why or why not?

- What is a treaty? What role do treaties play in U.S. law?

- List terms that refer to three legal principles that cause the status of American Indians to be a complicated issue. (Define each term.) Identify at least one advantage and one disadvantage of each principle for Native Americans.

Activity 1.2