2 Triangulating teaching growth: A three-voice approach to evaluating and documenting your teaching

Terri A. Dunbar; Peggy Brickman; and Janette R. Hill

For many universities, student evaluations of teaching (SETs) are synonymous with teaching evaluation. Universities typically administer surveys to students at the end of the semester, year after year, to solicit evaluations of their instructors’ teaching. Instructors report their scores as evidence of their teaching excellence for formal evaluations. Different academic units review these scores while making consequential decisions, such as raises or promotions. For better or worse, SETs are deeply embedded within the academic evaluation system.

In the United States, institutions rely on SETs to evaluate teaching performance more than any other measure of teaching (Miller & Seldin, 2014). Overreliance on SETs makes it more challenging to recognize effective and evidence-based teaching, however. SETs are known to be biased, meaning factors other than the quality of instruction influence how students respond to the survey items including characteristics of the instructor (e.g., gender, Adams et al., 2022, Owen et al., 2024; race, Smith & Hawkins, 2011; native language, Fan et al., 2019), course (e.g., class size, Bedard & Kuhn, 2008; quantitative vs. non-quantitative, Uttl & Smibert, 2017), and students (e.g., gender, Tucker, 2014; expected grade, Wang & Williamson, 2022). SETs also have weak and inconsistent relationships with student outcomes, such as learning (Uttl et al., 2017). Therefore, differences in SET scores may not reflect actual differences in teaching effectiveness.

Robust and equitable teaching evaluation means considering multiple perspectives to evaluate teaching, which reduces the limitations and potential biases of any single measurement (Weaver et al., 2020). To this end, this chapter introduces a holistic approach to teaching evaluation, the three–voice model (TEval, 2019), which considers student, peer, and instructor voices as critical to evaluation. Following this introduction, we offer practical guidance for instructors on how to gather multiple sources of evidence, document teaching using the three–voice model, and triangulate across voices to demonstrate growth.

Three-Voice Model

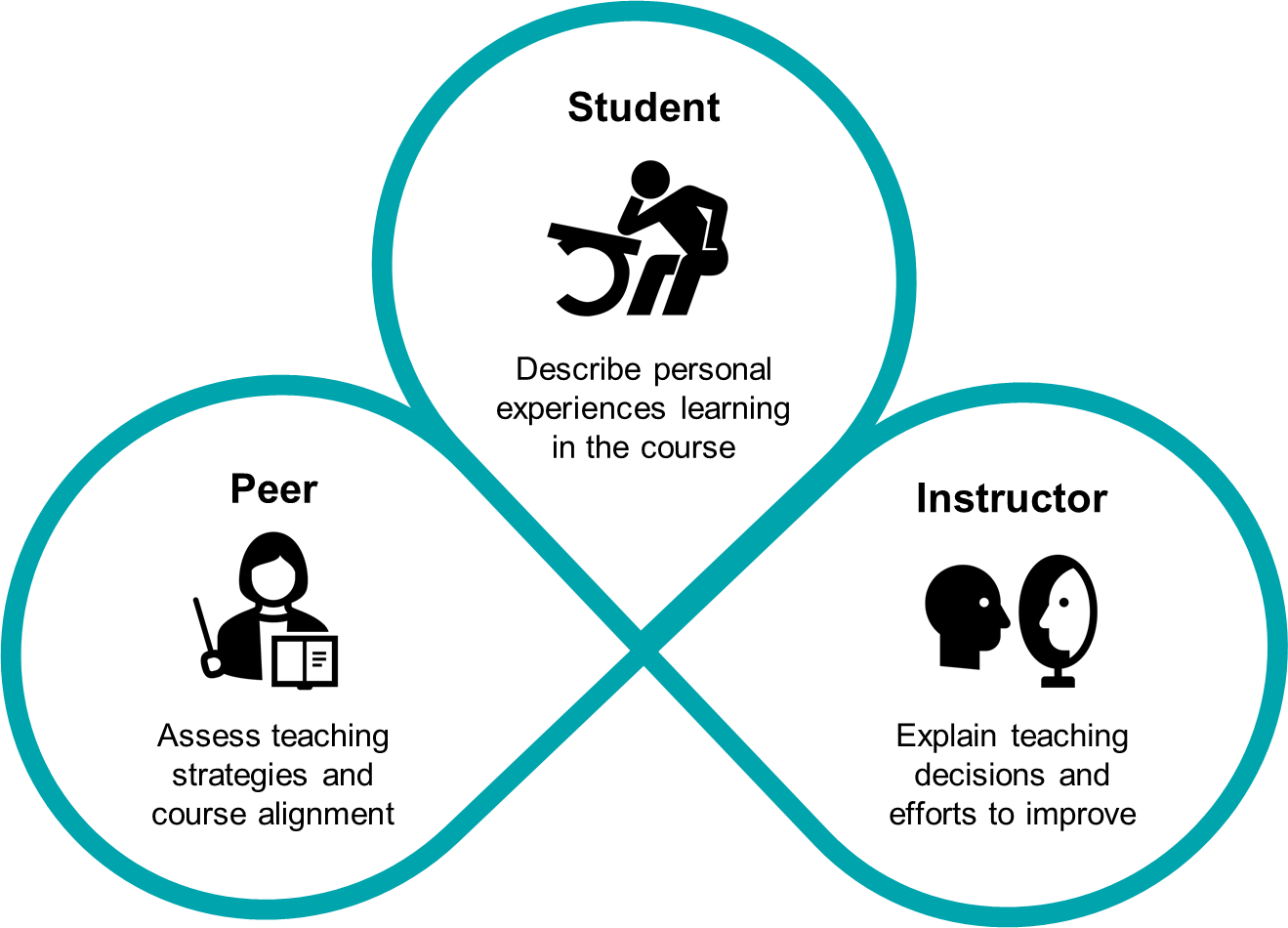

The three-voice model emphasizes using three sources of evidence (i.e., student, peer, instructor) to improve teaching over time and to evaluate teaching effectiveness (TEval, 2019). Figure 1 shows a visual representation of the model. Each voice highlights a unique perspective of an instructor’s teaching, speaking to different strengths and weaknesses. Although all three perspectives present their own biases, triangulating across them minimizes the influence of bias from any individual voice.

Figure 1

Three-Voice Model

The three-voice model expresses a common theme from several teaching evaluation frameworks, which state that evaluating teaching using the three voices provides additional insight into an instructor’s teaching beyond what a single voice can offer (Andrews et al., 2020; Finkelstein et al., 2020; NASEM, 2020; TEval, 2019; Weaver et al., 2020). The frameworks that underlie the model align components of effective teaching (e.g., classroom climate, evidence-based teaching) with multiple measures from the three voices (e.g., SETs, peer observations, self-reflection) to provide formative feedback on teaching and evaluate faculty for summative reviews. Similar frameworks include other perspectives, such as external reviewers (e.g., Framework to Assess Teaching Effectiveness; Simonson et al., 2022) or theories of teaching and learning (e.g., Four Lenses of Critical Reflection; Brookfield, 2017). However, when we sought to advance teaching evaluation at our institution, we found the three-voice model worked best for our context as it offered departments the most flexibility. The three-voice model now serves as the framework for our institutional teaching evaluation policy, which provides guidance for departments on how to incorporate the three voices into their departmental teaching evaluation process.

The first voice comes from students who are the “end users” of teaching. Their perspectives are typically gathered through SETs, but may be collected through other means (e.g., mid-semester feedback). Students speak to their day-to-day experience in class and with assessments, course materials, and interactions with the instructor. Another important source of information from students is their performance on assessments, which allows instructors to assess student learning outcomes to evaluate their teaching. Because responses on SETs may not reflect actual teaching quality (Carpenter et al., 2020), student voices shine best when focused on their lived experiences rather than judging the quality of instruction.

The second voice comes from peers who are colleagues of similar professional status that are also qualified to provide feedback on teaching (Chism, 2007). This qualification typically involves training to mitigate bias and improve accuracy in making judgments when providing feedback (Krishnan et al., 2022). Peers may evaluate teaching under several different circumstances, including hiring, promotion or tenure, post-tenure review, and teaching awards. Regardless of the purpose, peers provide an expert perspective on teaching through classroom observations or review of course materials. Peers from the same discipline are well-positioned to evaluate the alignment of course content and skills within the discipline and consider difficulties students face learning discipline-specific core concepts. Peers from any discipline can offer constructive and concrete feedback about an instructor’s teaching irrespective of the content. In general, peer voices speak to the effectiveness of the instructor’s teaching strategies.

The last voice comes from the instructors themselves; in other words, the instructors whose teaching is being evaluated. An instructor’s self-evaluation is less biased and more accurate when systematic documentation processes are used (Krishnan et al., 2022). Instructors may be asked to explain why they made certain teaching decisions, interpret feedback received from students or peers, describe efforts they took to improve their teaching (e.g., participating in professional development, critical self-reflection), and outline future teaching-related goals. The instructor’s voice is an important part of teaching evaluation because they are the most aware of the intent behind their actions. Instructors are the thread that ties all three voices together into a coherent picture.

Evaluating and Documenting Teaching Using the Three Voices

Each voice emphasizes different aspects of teaching, such as the student experience, an expert’s external perspective, and the instructor’s internal perspective. When examined holistically, the three voices offer instructors a better understanding of their strengths and weaknesses and generate multiple sources of evidence to help document teaching excellence. In this section, we provide examples of how instructors can evaluate and document their teaching using the three voices.

Student Voice

Instructors can use student voice to document their teaching by sharing student feedback about their experiences in the course and providing evidence of student learning. Both methods suffer from limitations and instructors should take caution in how they interpret and summarize each. As discussed previously, measurement tools such as SETs provide a biased perspective of teaching (Carpenter et al., 2020). Students speak well to their personal experiences in the course, but not necessarily to teaching quality. Evidence of student learning is also limited because factors other than teaching quality affect student performance such as self-regulation of motivation (Kryshko et al., 2020), academic goal orientation (Alhadabi & Karpinski, 2020), and academic and family stress (Deng et al., 2022). Despite these limitations, student voices are a critical part of an instructor’s teaching story and an easily accessible source of feedback. Table 1 lists example sources of evidence for student voice, highlights each source’s benefits and challenges, and shares resources for instructors to learn more.

Table 1

Example Sources of Evidence for Student Voice

|

Evidence |

Benefits |

Challenges |

Resources |

|

Student Evaluations of Teaching |

Commonly administered at institutions. Surveys change infrequently, making it easier to document longitudinal changes. |

Susceptible to bias. Results may not reflect actual teaching effectiveness. Qualitative analysis is time consuming. |

Overview of analyzing and interpreting SETs (Ory, 2006). Guidance for conducting qualitative analysis of SETs (Poproski, n.d.). |

|

Mid-Semester Feedback |

More flexible and adaptable than SETs. Current students will benefit from changes made based on their feedback. |

Time, resources, and knowledge of survey software. Students have fewer incentives to complete the survey. Not all feedback is actionable. |

Soliciting and utilizing mid-semester feedback (Marx, 2019). Impact of mid-semester feedback on students (Hurney et al., 2014). |

|

Classroom Assessment Techniques (CATs) |

Receive real-time feedback on teaching and learning process. Easy to implement during class. Can be used to iteratively refine a course during semester. |

Time consuming to analyze. Since CATs are ungraded, students may be less motivated to participate. |

Comprehensive book on CATs (Angelo & Zakrajsek, 2024).

|

|

Student Performance on Assessments |

Collected as part of course. Most direct evidence of student learning. Highlighting exemplary student work can be compelling and refreshing in dossiers, especially when visual. |

Affected by factors other than teaching quality. Student work must be anonymized and only used with student permission. Difficult for evaluators to assess quality of student work without rubrics. |

Using student learning outcomes to evaluate teaching (Berk, 2014).

|

Student feedback can be documented through SETs or mid-semester feedback. Feedback lends itself well to highlighting continuous improvement. We recommend instructors document their efforts using student feedback to inform course design decisions and improve their teaching. In addition, because student feedback is abundantly available, it allows instructors to track changes in instructional quality over time. The best method to document student feedback depends on the type of data being represented.

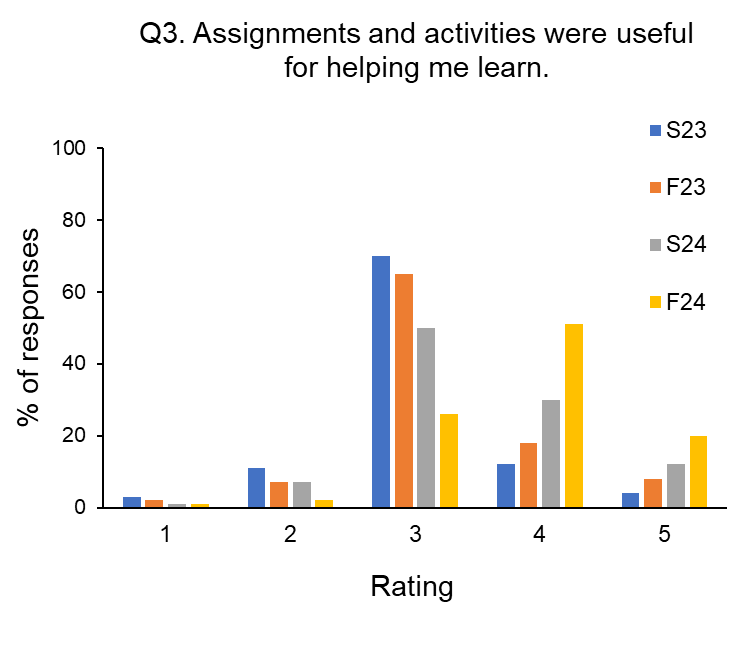

Student feedback includes both quantitative (e.g., numeric ratings) and qualitative (e.g., open-ended responses) data. Because responses to quantitative questions on SETs are often negatively skewed (i.e., more students select higher ratings than lower ratings) and not normally distributed, means are not the best representation of the data (Linse, 2017). Instead, instructors should graph the distribution of responses across each response option using bar graphs for specific questions (Figure 2). A single bar graph can include multiple courses or semesters/years, but including both reduces visibility and understandability. If needed, tables can summarize quantitative responses across several questions. To document qualitative responses, instructors can summarize common themes for open-ended questions and share representative quotes for each theme as space allows. In addition to summarizing the feedback, instructors should provide additional context about the course, share their interpretations of the findings, and explain how the feedback informed changes in instruction.

Figure 2

Example Bar Graph Showing Distribution of Responses

Evidence of student learning can be documented through classroom assessment techniques (CATs) and student performance on assessments. CATs are in-class, non-graded activities that provide real-time feedback on teaching and learning (Angelo & Zakrajsek, 2024); for example, asking clicker questions to assess how well students understand new concepts or using the muddiest point exercise to identify which part(s) of the lesson students find the most challenging. Instructors can use CATs to document their teaching by describing changes in student responses across the semester or by explaining how the results informed instructional changes mid-semester. Student performance (e.g., grades) can be examined across a semester, across courses, or within a single course over time and documented graphically. When instructors make significant changes to their teaching, student performance can be used to point out the effectiveness of these changes. Anonymous samples of student work are an alternative and more qualitative way to document student performance.

Peer Voice

Peers offer valuable insights for instructors to document how well their teaching supports student learning, including feedback on instructional strategies, teaching materials, assessments, learning goals, and curriculum alignment (Chism, 2007). Instructors typically value constructive feedback more when shared by peers compared to students (Brickman et al., 2016). In addition to formative evaluations, peers can also assess the quality of an instructor’s teaching for summative evaluations (e.g., promotion and tenure). Peer voice comes in several forms including observations, conversations, and review of teaching materials. Each form has benefits and challenges in how it provides instructors with a voice to inform their teaching practice (see Table 2 for a summary).

Table 2

Example Sources of Evidence for Peer Voice

|

Evidence |

Benefits |

Challenges |

Resources |

|

Observations |

Provides real-time feedback on instruction. Can discuss teaching before, during, and after the observation. Opportunities for growth for observer and instructor. |

Time for scheduling meetings and observation. Determining focal point for the observation(s). Without observer training, feedback quality may be poor. |

Practical guidance on implementing peer observation (Bandy, 2015; Tse, 2022). Comprehensive book on peer review of teaching (Chism, 2007). Review of peer observation literature (Thomas et al., 2014). |

|

Conversations with Colleagues |

Receive suggestions from multiple colleagues. Defined focus on a specific area of teaching or on teaching overall. Greater opportunity for autonomy. |

Feedback can be overly generalized and lack specificity. Conversations may be less directive and lack a focal point. |

Informal networks instructors use to talk about teaching (Roxå & Mårtensson, 2009). Building integrated networks to develop teaching (Taylor et al., 2022). |

|

Peer Review of Teaching Materials |

Offers multiple perspectives on teaching beyond classrooms. Can revise materials prior to using them. Opportunity to improve presentation of teaching practices for larger audiences. |

Time to review and implement feedback. Deciding which feedback to incorporate. |

Rubric for evaluating online and blended courses (CSU, 2022). Guidance for review of teaching materials (Chism, 2007). |

Peer observations are perhaps the most widely known form of peer voice. Observations may be “one and done” or occur multiple times. Providing structure through a rubric can be useful because it standardizes the observation process and provides guidance on what behaviors observers should look for in the classroom (Krishnan et al., 2022). Rubrics can be designed to focus on the observed session and to provide general feedback on teaching. Observers should be trained to help ensure they understand the peer observation process and can generate constructive feedback (Carroll & O’Loughlin, 2014). Creating time to meet before and after the observation also enhances the experience because it enables time for discussion, questions, and critical reflection on teaching (Heron et al., 2024). However, time is frequently cited as a challenge with peer observations (Kell & Annetts, 2009) and it is the dialogue before, during, and after the observation that is one of the greatest benefits.

Conversations with colleagues allow instructors to gather feedback from multiple peers simultaneously. Instructors can discuss teaching in different venues, such as departmental faculty meetings or meetings in faculty learning communities run by a teaching center. These conversations may be open-ended so the group can discuss teaching practices in general, or related to a specific topic of interest such as engagement in online classes. Diverse constructions of the group (e.g., across disciplines or experience levels) may also facilitate multiple forms of feedback and knowledge sharing. While challenges such as focal point and maintaining constructive conversations may occur, these collegial conversations offer instructors an outlet to discuss their teaching and receive the emotional, academic, and professional support they desire but often lack (Rienties & Hosei, 2015; Roxå & Mårtensson, 2009).

Review of teaching materials or portfolios is another source of feedback for peer voice. Teaching portfolios are curated collections of materials that document an instructor’s teaching responsibilities, philosophy, goals, and accomplishments (Seldin et al., 2010). Materials review can include any number of teaching related documents, ranging from a syllabus to instructional materials to a quiz or exam. It may also include online courses in learning management systems. Review of teaching portfolios created at major points of review (e.g., promotion, awards) offers another opportunity for peer feedback (Shah et al., 2020). Having a colleague review a teaching portfolio can help instructors edit and improve the overall presentation of their teaching experience. Peer review of teaching materials at any level provides an opportunity to improve teaching practices and additional evidence to document teaching excellence (Chism, 2007).

Various strategies can be used to document teaching practices for peer feedback. For observations, instructors can share the syllabus along with materials specific for the observed session(s). Colleagues may review assigned readings or other relevant course materials prior to a conversation. Instructors can create and share a teaching portfolio through an online platform (e.g., LMS, web-based drive) to enable convenient access to all materials being reviewed by peers.

Instructor Voice

Instructor self-reflection provides one of the most powerful mechanisms to influence professional development (Kreber & Cranton, 2000). Deliberate and thoughtfully crafted written narratives serve as a crucial avenue for self-reflection (McAlpine et al., 2010). These narratives assume several forms, including reflecting on videos of one’s teaching or other teaching artifacts (e.g., assessments, annotated student work). Narratives offer instructors the chance to comment on their course goals and whether these goals were met, share information about student outcomes to inform future teaching, and reflect on how to improve communication with students about instructional goals and strategies for success. Self-reflection also provides the opportunity to integrate feedback from student and peer voices with data from a systematic analysis of student learning to revise and improve instruction (Centra, 1993). Lastly, self-reflection forms the foundation for scholarship in teaching and learning, contributes to the development of pedagogical knowledge, and encourages on-going information seeking from peers and students. Table 3 shares a breakdown of the affordances, challenges, and resources to complete multiple forms of self-reflection, each of which supports a practice with a profound influence on instructor development (Kreber & Cranton, 2000).

Table 3

Example Sources of Evidence for Instructor Voice

|

Evidence |

Benefits |

Challenges |

Resources |

|

Notes from Regular Reflections |

Aids reflection in major teaching categories. |

Experience, education, and personal preferences differ between instructors, so uniform use may be challenging. Requires time and effort to synthesize into a format usable in teaching portfolios or reflective documents. |

Consider the following categories: Instructional (construct learning objectives, test items, sequence instruction). Pedagogical (facilitate collaboration, motivate students, help students overcome learning difficulties). Curricular (explain how course fits into program, learning skills). |

|

Reviewing Video Recordings of Your Teaching |

Best method to “see” your teaching and prompt critical reflection. Checklists exist to tally behaviors and prompt reflection. May benefit from debrief with and guidance from a colleague. |

Recording may threaten instructors’ self-esteem. Technology is challenging and time-consuming. Using a guiding framework is important to focus reflection. Without training, instructors may be unclear about what to focus on and may overemphasize personal preferences. |

Guide to using video to review teaching (Tripp & Rich, 2011). |

|

Protocols for Self-Reflection |

Helps instructors continuously improve teaching through systematic analysis of data. Can document teaching in ways that may not be captured by students or peers. |

Often lacks specificity and depth without formal structure or prompts. Requires pedagogical understanding to best express instructional decisions. Requires time and effort to synthesize into a format usable for formal evaluations. |

Self-reflection question prompts (Kirpalani, 2017; TEval, 2019). Teaching Practices Inventory (Wieman & Gilbert, 2014). |

|

Teaching Portfolio |

Provides thorough examples of teaching practices, content & alignment within curriculum, and evidence of student learning outcomes. |

Often lengthy and disorganized. May only highlight successes without opportunities to reflect on challenges. Difficult to evaluate. |

Guides to creating a teaching portfolio (Seldin et al., 2010; Tucker et al., 2013). Example supporting documents (TEval, 2019). Scoring rubric for teaching portfolios (Beckett et al, 2024). |

|

Teaching Philosophy |

Expresses values, teaching style, rationale for instructional decisions, and highlights best practices. Many instructors already possess one since these are often submitted for job applications. |

Daunting to write and often boring to read. May lack information about specific examples and skills. Requires pedagogical understanding to best express instructional decisions. Unclear how evaluators can identify and provide support to address challenges that are not the focus of the document. |

Guide to writing your teaching philosophy (Boye, 2012). Scoring rubric for teaching statements (Kearns et al., 2010). |

The process for evaluating teaching through self-reflection involves collecting evidence or systematic observation, analyzing evidence or observations, and reflecting on the findings to understand them (Andrews & Lemons, 2022). Although this process should be ongoing, the normal cycle of the semester presents natural reflective opportunities before, during, and after instruction. Before the semester starts, instructors can enact comprehensive plans to alter their courses and collect evidence of student learning. These plans should build on self-reflection from prior semesters and prompt systematic collection of data sources during the semester. These sources of evidence can be informal (e.g., notes from regular reflections based on interactions with students during class or office hours, grading assignments or exams, or teaching workshops) or formal (e.g., video recordings of teaching, student performance on assessments). After the semester, instructors can review the evidence to identify content challenges or instructional practices that hamper student learning and decide what steps they should take to improve (e.g., participate in teaching professional development).

To document this systematic process, instructors can use protocols for self-reflection or a teaching portfolio. Protocols for self-reflection provide prompts to document activities such as the type of courses taught, number of students, learning objectives, activities, accomplishments, and challenges (Kirpalani, 2017). Teaching portfolios allow instructors to demonstrate their teaching excellence and show how their teaching practices align with their teaching philosophy (Seldin et al., 2010). The standard teaching portfolio includes a narrative of teaching responsibilities, teaching philosophy statement, and evidence of teaching effectiveness. The prompts for self-reflection provide a good base for developing a written narrative of teaching responsibilities. To draft a teaching philosophy, instructors should reflect on their values, beliefs, and goals about teaching and learning, and then identify evidence from their teaching that shows their values, beliefs, and goals in action (Boye, 2012). The systematic self-reflection process often produces ample evidence of teaching effectiveness, and instructors are encouraged to reflect on feedback received from students and peers for additional evidence.

Triangulating Teaching Growth

One strength of the three-voice model is that it provides a balanced framework for demonstrating teaching excellence while reducing the limitations inherent in any single voice (Weaver et al., 2020). To apply the model, we encourage instructors to collect multiple sources of evidence from each voice at different time points, when possible. Because this process takes time, instructors should begin early and gather evidence consistently throughout their teaching career. Doing so not only supports ongoing growth through regular feedback and reflection but also builds a robust body of evidence for documenting teaching for summative reviews. After data collection, instructors can then triangulate across the diverse sources of evidence to identify patterns or common findings. When instructors use multiple sources to document their teaching, they make a stronger and more credible case for their excellence in the classroom.

Creating a Theme

Once feedback has been gathered from student, peer, and instructor voices, instructors can start making sense of the information. Like many forms of feedback (e.g., annual evaluations, peer review of research), teaching feedback elicits both cognitive and emotional reactions. The following 4-step process, adapted from Poproski (n.d.), provides a foundation for instructors to process the feedback, develop themes, and generate next steps or actions to take to improve their subsequent teaching.

The first step is an overall review of the information. Instructors should read through the various feedback provided (e.g., SETs, peer observation rubrics, self-reflection notes). At this stage, it is important to avoid making judgments while reading. Instead, focus on understanding the overall collection of feedback and its content. This broad overview will enable a “big picture” of the gathered feedback.

Next, instructors need time to react and reflect (good, bad, indifferent) to the feedback they are reviewing. Reviewing feedback on teaching can be daunting, especially when the feedback is not constructive. Instructors should take time to let themselves experience their emotions during the initial read through. It is also important to pause before moving on to the next phase, revisiting the information. Taking a break allows instructors to come prepared to review the feedback with a more objective eye.

Following the react and reflect phase, it is time to revisit the information with a goal of understanding the feedback from the perspective of those providing it (e.g., students, peers). Analyzing the information using a systematic approach is also useful during this phase. Instructors can analyze quantitative data (e.g., Likert questions) by looking at means and distributions, then view the data by question or in larger categories to identify trends. The qualitative data (e.g., open-ended responses) can be sorted into categories (e.g., positive, constructive criticism, not actionable) to identify themes (e.g., positive feedback about instructional activities used to engage students, actionable feedback to improve assessments of learning). After analyzing the data, instructors should review all findings together to identify larger patterns and themes across multiple sources of information. When the three voices overlap, this provides strong support for an observable pattern. When the voices disagree, instructors should dig deeper to determine where these differences are coming from. For example, perhaps students, peers, and the instructor have different interpretations of the intent behind a specific teaching decision. These larger patterns and themes that triangulate across the voices are the most critical to reflect on and grow as an instructor.

Deciding how to respond and actions to take is the final step in creating themes from the voices. Instructors should determine which teaching practices they will continue doing or modify in future courses based on the feedback they received. Taking notes on this process of reviewing, analyzing, and reflecting on feedback can also be useful for future use when instructors need to demonstrate their growth in teaching.

Three-Voice Template

We created this template for instructors to document their teaching and instructional growth using the three voices. This template may be modified for multiple evaluation purposes (e.g., annual reviews or promotion and tenure). For annual reviews, inclusion of data from the past few semesters should suffice, whereas multiple years of data should be included when documenting teaching in promotion dossiers.

Student Voice

Summary of Student Qualitative Comments from End-of-Course Experience Surveys

Themes: Identify three major categories of comments to reflect on below.

- Which two teaching elements did students identify as being most beneficial to their learning? How can you maximize those elements in the future?

- Which items signal a need for improvement? What steps can you take to improve in these areas?

- What changes are you considering for the next time you teach this course?

Summary of Student Survey Items

Provide a graphical representation of Likert survey items, preferably over several semesters or years to document change over time (see Figure 2 for an example).

Explain trends observed from the data (e.g., More students (>80%) selected a 4/5 response across the spring of 2023, 2024, and 2025).

Report response rates for each semester (e.g., Spring 25: 148/200, 74%).

Peer Voice

Summary of Peer Feedback

Describe the types of feedback received from peers (e.g., peer observation, informal engagement with faculty learning community, working with co-instructors or instructors of subsequent courses to identify student challenges).

Themes: Identify 1-3 themes from peer feedback, then define each theme in a sentence or two and provide explanatory quotes to support the theme. For example:

- Removing Barriers: It was noted in my formal peer teaching evaluation by my department that my use of concept mapping and modeling helped students understand the relationships across concepts.

- “…[Dr. XXX] revisited main themes at multiple time points to help students understand these concepts and to link related concepts. Her use of an expanding flow-chart as an overview tool (across several class sessions) as she was teaching the nervous system, was an excellent approach to remind students of the big picture.”

Evidence of Teaching Effectiveness from Other Categories

Provide descriptions of awards, recognition, or new courses developed to address critical needs in the department.

Self-Voice

Describe the three most significant accomplishments made toward teaching this year using the following prompts.

Accomplishment 1: Efforts made to identify areas for improvement in teaching. For example:

- Collecting assessment data or student feedback to recognize when they have not met learning outcomes.

- Example sources of evidence: Course assessment data like final exams, reflective notes after grading a test or project with possible suggested changes, mid-semester student feedback, SETs, video recordings of student performance, feedback from teaching assistants.

- Reflecting on evaluations by peers and students to identify areas for improvement in instructional practice.

- Example sources of evidence: Mid-semester student feedback, SETs, peer observations.

Accomplishment 2: Efforts made to improve the course. For example:

- Attending professional development opportunities.

- Example sources of evidence: Attendance at teaching center-sponsored events, workshops, or learning communities.

- Proposing or implementing significant changes to the course or showing why content should be kept the same because of this analysis.

- Example sources of evidence: Higher education literature, discussions from a faculty learning community or curricular group, revision or review of current course objectives or syllabi, peer review of teaching materials, peer observations.

- Trying something new in a course and critically reflecting on how it worked.

- Example sources of evidence: Notes from regular reflection.

- Engaging in course review or feedback.

- Example sources of evidence: Mid-semester student feedback, peer observations, peer coaching or mentoring.

Accomplishment 3: Evidence that shows how one’s teaching has changed and improved because of assessment or self-analysis. For example:

- Updated course content for accuracy, relevancy, or new discoveries in the field.

- Example sources of evidence: Higher education literature, teaching portfolio with assignments or assessments before and after the changes, updated syllabi.

- Changed course materials because of feedback from students or peers.

- Example sources of evidence: Teaching portfolio, altered course assessments, assessment data pre-post implementation of change.

Conclusion

This chapter introduced the three-voice model as an alternative framework to document teaching excellence, moving beyond traditional SETs to incorporate multiple perspectives in teaching evaluation. The three voices—student, peer, and instructor—complement each other, with each offering unique insights into an instructor’s teaching. Students can emphasize their personal experience in the course. Peers can offer feedback on alignment with learning outcomes and the effectiveness of teaching strategies. Instructors voice their own teaching narrative, integrating the other perspectives as evidence of their growth and to explain the reasoning behind pedagogical decisions. By triangulating across these voices, a richer and more holistic view of teaching emerges that goes beyond what SETs alone can capture.

While the examples provided in this chapter are not exhaustive, they offer a valuable starting point for instructors to diversify the feedback they gather on their teaching. We encourage instructors to first assess the sources of evidence already available at their institution, and then evaluate how well these sources represent the three voices. For areas where certain voices are underrepresented, instructors might consider incorporating additional feedback using the examples in this chapter to strengthen their upcoming annual review or promotion dossier. Ultimately, embracing this comprehensive approach to evaluation can foster continuous improvement in teaching and a deeper understanding of what constitutes excellence in the classroom.

References

Adams, S., Bekker, S., Fan, Y., Gordon, T., Shepherd, L. J., Slavich, E., & Waters, D. (2022). Gender bias in student evaluations of teaching:‘Punish [ing] those who fail to do their gender right’. Higher Education, 83, 787–807. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00704-9

Alhadabi, A., & Karpinski, A. C. (2020). Grit, self-efficacy, achievement orientation goals, and academic performance in University students. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 519–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2019.1679202

Andrews, S. E., Keating, J., Corbo, J. C., Gammon, M., Reinholz, D. L., & Finkelstein, N. (2020). Transforming teaching evaluation in disciplines: A model and case study of departmental change. In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, and L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming institutions: Accelerating systemic change in higher education. Pressbooks.

Andrews, T., & Lemons, P. (2022). Faculty self-reflection guide. University of Georgia. https://ctl.uga.edu/wp-content/uploads/faculty-self-reflection-guide.pdf

Angelo, T. A., & Zakrajsek, T. D. (2024). Classroom assessment techniques: Formative feedback tools for college and university teachers (3rd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Bandy, J. (2015). Peer review of teaching. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. https://derekbruff.org/vanderbilt-cft-teaching-guides-archive/peer-review-of-teaching/

Beckett, R. D., Sheehan, A. H., Isaacs, A. N., Ramsey, D., & Sprunger, T. (2024). Development and assessment of a rubric for evaluating teaching portfolios developed by teaching and learning curriculum (TLC) program participants. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 88(9), 101262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpe.2024.101262

Bedard, K., & Kuhn, P. (2008). Where class size really matters: Class size and student ratings of instructor effectiveness. Economics of Education Review, 27(3), 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2006.08.007

Berk, R. A. (2014). Should student outcomes be used to evaluate teaching? The Journal of Faculty Development, 28(2), 87–96.

Boye, A. (2012). Writing your teaching philosophy. Teaching, Learning, and Professional Development Center, 1–7.

Brickman, P., Gormally, C., & Martella, A. M. (2016). Making the grade: Using instructional feedback and evaluation to inspire evidence-based teaching. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 15(4), ar75. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.15-12-0249

Brookfield, S. D. (2017). Becoming a critically reflective teacher (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

California State University (2022). Quality learning and teaching rubric 3rd edition. https://ocs.calstate.edu/rubrics/qlt

Carpenter, S. K., Witherby, A. E., & Tauber, S. K. (2020). On students’ (mis)judgments of learning and teaching effectiveness. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 9(2), 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2019.12.009

Carroll, C., & O’Loughlin, D. (2014). Peer observation of teaching: Enhancing academic engagement for new participants. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 51(4), 446–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2013.778067

Centra, J. A. (1993). Reflective faculty evaluation: Enhancing teaching and determining faculty effectiveness. Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education.

Chism, N. V. N. (2007). Peer review of teaching: A sourcebook (2nd ed.). Anker Publishing.

Deng, Y., Cherian, J., Khan, N. U. N., Kumari, K., Sial, M. S., Comite, U., Gavurova, B., & Popp, J. (2022). Family and academic stress and their impact on students’ depression level and academic performance. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 869337. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.869337

Fan, Y., Shepherd, L. J., Slavich, E., Waters, D., Stone, M., Abel, R., & Johnston, E. L. (2019). Gender and cultural bias in student evaluations: Why representation matters. PLoS ONE, 14(2), e0209749. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0209749

Finkelstein, N., Greenhoot, A. F., Weaver, G., & Austin, A. E. (2020). A department-level cultural change project: Transforming evaluation of teaching. In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, and L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming institutions: Accelerating systemic change in higher education. Pressbooks.

Heron, M., Donaghue, H., & Balloo, K. (2024). Observational feedback literacy: Designing post observation feedback for learning. Teaching in Higher Education, 29(8), 2061–2074. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2023.2191786

Hurney, C., Harris, N., Bates Prins, S., & Kruck, S. E. (2014). The impact of a learner-centered, mid-semester course evaluation on students. The Journal of Faculty Development, 28(3), 55–62.

Kearns, K. D., Subiño Sullivan, C., O’Loughlin, V. D., & Braun, M. (2010). A scoring rubric for teaching statements: A tool for inquiry into graduate student writing about teaching and learning. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 21(1), 73–96.

Kell, C., & Annetts, S. (2009). Peer review of teaching embedded practice or policy‐holding complacency? Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 46(1), 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703290802646156

Kirpalani, N. (2017). Developing self-reflective practices to improve teaching effectiveness. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 17(8), 73–80.

Kreber, C., & Cranton, P. A. (2000). Exploring the scholarship of teaching. The Journal of Higher Education, 71, 476–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2000.11778846

Krishnan, S., Gehrtz, J., Lemons, P. P., Dolan, E. L., Brickman, P., & Andrews, T. C. (2022). Guides to advance teaching evaluation (GATEs): A resource for STEM departments planning robust and equitable evaluation practices. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 21(3), ar42. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.21-08-0198

Kryshko, O., Fleischer, J., Waldeyer, J., Wirth, J., & Leutner, D. (2020). Do motivational regulation strategies contribute to university students’ academic success? Learning and Individual Differences, 82, 101912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2020.101912

Linse, A. R. (2017). Interpreting and using student ratings data: Guidance for faculty serving as administrators and on evaluation committees. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 54, 94–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2016.12.004

Marx, R. (2019). Soliciting and utilizing mid-semester feedback. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. https://derekbruff.org/vanderbilt-cft-teaching-guides-archive/soliciting-and-utilizing-mid-semester-feedback/

McAlpine, L., Weston, C., Berthiaume, D., Fairbank-Roch, G., & Owen, M. (2010). Reflection on teaching: Types and goals of reflection. Educational Research and Evaluation, 10(4-6), 337–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803610512331383489

Miller, J. E., & Seldin, P. (2014). Changing practices in faculty evaluation. American Association of University Professors. https://www.aaup.org/article/changing-practices-faculty-evaluation

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2020). Recognizing and evaluating science teaching in higher education: Proceedings of a workshop—in brief. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25685

Ory, J. C. (2006, July 1). Getting the most out of your student ratings of instruction. Association for Psychological Science. https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/getting-the-most-out-of-your-student-ratings-of-instruction

Owen, A. L., De Bruin, E., & Wu, S. (2024). Can you mitigate gender bias in student evaluations of teaching? Evaluating alternative methods of soliciting feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2024.2407927

Poproski, R. (n.d.). Interpreting and responding to student evaluations of teaching. University of Georgia Center for Teaching and Learning. https://ctl.uga.edu/teaching-resources/feedback-and-evaluation-of-teaching/interpreting-responding-to-student-evaluations-of-teaching/

Rienties, B., & Hosein, A. (2015). Unpacking (in)formal learning in an academic development programme: A mixed-method social network perspective. International Journal for Academic Development, 20(2), 163–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2015.1029928

Roxå, T., & Mårtensson, K. (2009). Significant conversations and significant networks–Exploring the backstage of the teaching arena. Studies in Higher Education, 34(5), 547–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802597200

Seldin, P., Miller, J. E., & Seldin, C. A. (2010). The teaching portfolio: A practical guide to improved performance and promotion/tenure decisions. John Wiley & Sons.

Shah, P., Laverie, D. A., & Madhavaram, S. (2020). Summative and formative evaluation of marketing teaching portfolios: A pedagogical competence-based rubric. Marketing Education Review, 30(4), 208–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/10528008.2020.1823235

Simonson, S. R., Earl, B., & Frary, M. (2022). Establishing a framework for assessing teaching effectiveness. College Teaching, 70(2), 164-180. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2021.1909528

Smith, B. P., & Hawkins, B. (2011). Examining student evaluations of Black college faculty: Does race matter? Journal of Negro Education, 80(2), 149–162.

Taylor, K. L., Kenny, N. A., Perrault, E., & Mueller, R. A. (2022). Building integrated networks to develop teaching and learning: The critical role of hubs. International Journal for Academic Development, 27(3), 279–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2021.1899931

TEval. (2019). Transforming higher education—Multidimensional evaluation of teaching. https://teval.net

Thomas, S., Chie, Q. T., Abraham, M., Jalarajan Raj, S., & Beh, L. S. (2014). A qualitative review of literature on peer review of teaching in higher education: An application of the SWOT framework. Review of Educational Research, 84(1), 112–159. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313499617

Tripp, T., & Rich, P. (2012). Using video to analyze one’s own teaching. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(4), 678–704. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2011.01234.x

Tse, C. (2022). Peer feedback on your teaching. Center for the Advancement of Teaching Excellence at the University of Illinois Chicago. https://teaching.uic.edu/resources/teaching-guides/reflective-teaching-guides/peer-feedback-on-your-teaching/

Tucker, B. (2014). Student evaluation surveys: Anonymous comments that offend or are unprofessional. Higher Education, 68, 347–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9716-2

Tucker, P., Stronge, J., & Gareis, C. (2013). Handbook on teacher portfolios for evaluation and professional development. Routledge.

Uttl, B., & Smibert, D. (2017). Student evaluations of teaching: Teaching quantitative courses can be hazardous to one’s career. PeerJ, 5, e3299. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.3299

Uttl, B., White, C. A., & Gonzalez, D. W. (2017). Meta-analysis of faculty’s teaching effectiveness: Student evaluation of teaching ratings and student learning are not related. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 54, 22–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2016.08.007

Wang, G., & Williamson, A. (2022). Course evaluation scores: Valid measures for teaching effectiveness or rewards for lenient grading? Teaching in Higher Education, 27(3), 297–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1722992

Weaver, G. C., Austin, A. E., Greenhoot, A. F., & Finkelstein, N. D. (2020). Establishing a better approach for evaluating teaching: The TEval project. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 52(3), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2020.1745575

Wieman, C., & Gilbert, S. (2014). The teaching practices inventory: A new tool for characterizing college and university teaching in mathematics and science. CBE – Life Sciences Education, 13(3), 552–569. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.14-02-0023