1 The teaching dossier as genre: A SoTL-informed approach to documenting teaching excellence

Shannon M. Sipes and Michael Morrone

This chapter argues a teaching dossier (the primary outlet for documenting teaching effectiveness) is its own genre of academic writing and that the scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) provides the most effective cross-disciplinary lens in which to engage with this genre. Salient defining characteristics of the genre are its purpose–to evaluate teaching quality, stakeholders–the faculty member who writes and complies the dossier and evaluating readers, and sub-genres such as teaching philosophy statements and curricula vitae. The genre’s core purpose, to evaluate teaching quality, also serves as a core purpose of SoTL, with peer review making the evaluations “akin to judgments made about manuscripts or funding proposals for editors or grant officers” (Bernstein, 2008, p. 48).

In making this argument, the chapter provides delineations of genre and SoTL, interweaving explicit examples of how both the process of creating the dossier and the product itself fit within the operationalized definitions of each adopted by the authors. Although the examples provided throughout the chapter focus primarily on the promotion process, SoTL as a lens for evaluating teaching dossiers effectively grounds writing and reading of dossiers in other contexts such as hiring, retention, and teaching awards. Each of the chapter authors brings a unique perspective to making this argument.

As the director for the SoTL program for the Indiana University Bloomington campus and lead instructional consultant in the teaching center, Shannon Sipes supports faculty in implementing, investigating, and documenting evidence-based approaches to teaching and learning. In this position she thinks about how the mostly unseen pedagogical work of instructors can be made seen through the use of rhetoric, data, and products valued in the academy.

Michael Morrone’s approach to documenting teaching excellence is colored by his decade of leadership of Indiana University’s Faculty Academy on Excellence in Teaching, attainment of the highest non-tenure track teaching rank at Indiana University, and opportunities stemming from his status as a white, male, cisgender faculty member at a large, predominantly white institution. He is dedicated to recognizing excellent teaching regardless of discipline, philosophical underpinnings, or an instructor’s background.

Evaluation of Teaching

Every faculty member will face evaluation of teaching for administrative purposes regardless of their contract status. Faculty on the tenure track pass through a series of reviews at regular intervals as they achieve promotion to advance through their careers. A growing number of institutions are employing faculty in contract renewable teaching tracks that follow a similar promotion process as tenure track lines, but without the security of tenure at the end. Evaluation of teaching informs hiring and retention decisions for all faculty including part-time faculty. Finally, teaching awards, whether for full-time and part-time faculty, require the application of criteria of effectiveness and excellence to determine awardees.

For tenure track faculty in the United States, probationary faculty status typically lasts up to 7 years (Andrews, 2009). During this time, the faculty member will draft an argument for promotion to non-probationary status and compile selected evidence, a dossier, of quality work to share for peer review by promoted colleagues both internal and external to the faculty member’s institution. Both the internal and external reviewers typically access the institutional promotion criteria and evaluate the provided evidence against the criteria. In the end, the reviewers will vote on promotion and articulate the degree to which they agree with the argument.

The promotion process typically occurs as an annual cycle. This cycle establishes a rhetorical situation in which the promotion candidate’s private argument for promotion becomes public and subject to social action. During this cycle both the writer’s role in compiling a teaching dossier, and subsequently, the readers’ evaluation of the dossier reinforces the notion that a dossier is one of the most important career-related genres in higher education.

Similar to the promotion context, selection processes for teaching awards and recognition of teaching excellence often rely on dossiers. For example, at Indiana University the university president’s selection of a wide variety of teaching awards follows faculty review of nominee dossiers. Several Indiana University campuses require dossiers for faculty review to support selection of the Trustees Teaching Awards as does selection to the University-wide Faculty Academy on Excellence in Teaching (FACET).

Teaching Dossier as Genre

We are not the first to claim academia has its own genre. A university’s genre system is made up of materials unique to students, professors, administrators, and staff (Auken, 2020). Within the university genre system is a subset referred to as academic promotional materials; including university brochures (Osman, 2006), tenure and promotion evaluations (Hyon, 2008), dissertations and academic papers (Hyon, 2008), Fulbright grant application (Casal & Kessler, 2020), and teaching philosophy statements (Wang, 2023).

In this chapter, we adopt the view of genre as social action. In this view “a genre is a rhetorical means for mediating private intentions and social exigence; it motivates by connecting the private with the public, the singular with the recurrent” (Miller, 1984, p. 163) and thus the expression of teaching with the review committee. Understanding a genre allows the reader to understand the motives and goals of the writer before they begin to engage with the product for any given situation (Russel, 2023). In the case of a teaching dossier, the private intention of the creator is to achieve promotion, a teaching award, a grant, or similar. This intention becomes public when the dossier is shared with the appropriate review committee. Over time, this process has become the systematic way the creator and the reader interact in the social environments tied to these goals. The dossier as genre informs both decisions in response to the private intention and the ongoing evolution of criteria and process.

“Knowledge of a genre is generally accessible only to the members of the discourse community the genre belongs to” (Osman, 2006, p. 112). In the case of academic promotional materials such as teaching philosophy statements, teaching dossiers, and tenure and promotion evaluations, the discourse community consists of the teacher creating the materials, their academic peers and administrators reviewing the materials, and anyone else the teacher shares the materials with (i.e. students or colleagues). Therefore, access to example materials within this genre are only available to those who have successfully written in the genre or the informal network of mentors a teacher has access to.

Genres do not exist in isolation, but in patterns related to other genres and categorized by their social role (Russell, 2023). Universities provide guidelines to their community members on what to include within a teaching dossier with variability across institutions (Taylor & Charlebois, 2024). Deepening our understanding of the dossier as a genre increases our understanding of its structural organization and the sociocultural factors that influence the organization (Osman, 2006).

Within the academic discourse community, however, ascertaining what is a quality dossier remains complicated for both writers and evaluators of dossiers, as there is a lack of consensus about the best way to document teaching excellence (Barbeau & Cornejo Happel, 2023; Berk, 2018; Taylor & Charlebois, 2024). Guidelines for review of a dossier are abundant (ACE, AAUP, & United Educators, 2000; Miller, 2023; Prescott, 2023), but no such guidelines beyond a checklist exist for the writer to communicate their proficiency in each requirement. An instructor may be an excellent teacher, but failure to convey this in writing can be the difference in successfully achieving the goal for which the dossier is reviewed.

Due to the personal and confidential nature of the promotion process, teaching dossiers are typically semi-private, with faculty having limited if any exposure to examples before preparing their own. Given the significance they hold in a high stakes decision-making process, it is critical we come to a shared and transparent understanding of the expectations for the dossier. Wang (2023) claims statements of teaching are “a critical, high-stakes genre that academics must master for their career development and success in the face of increasing institutional demands and fierce job market competition” (p. 2). If one aspect of the teaching dossier holds potential for significant impact, how much more critical is mastering the genre of teaching dossier?

Documenting Teaching Excellence

Over the last several decades, documenting teaching excellence has become more nuanced, moving from relying primarily on student evaluations of teaching to a reality that dossiers must include multiple sources of evidence (Barbeau & Cornejo Happel, 2023; Cohen, 2003; Delgadillo, 2019; Simonson, Earl, & Frary, 2021). To complicate matters further, some review processes include colleagues external to the dossier writer’s university making judgments based on a subset of evidence contained in the full dossier (Indiana University, 2024; University of Houston, 2022). Colleagues internal to the dossier writer’s university are likely to work with a committee at the department, school, or campus level to discuss the dossier and vote on the promotion case or teaching award. Variations in process, audience, and standards for excellence that evolve as we learn more about effective teaching and learning create a daunting rhetorical situation for documenting teaching excellence.

Evaluators of teaching quality typically review a variety of documentation. On one hand it is well-established, or at least highly credible, that consideration of a variety of evidence contributes to an evaluation of teaching effectiveness. On the other hand, there is not agreement that a specific set of materials or evidence leads to an exact assessment. At minimum, a strong dossier should triangulate three sources of evidence of effective teaching: students, peers, and self (Berk, 2018; Taylor & Charlebois, 2024). Brookfield (1995) suggests the addition of a fourth source, theoretical literature. This practice removes the impact of a single source of data and provides a richer picture into one’s teaching.

Dossiers “demonstrate to potential gatekeepers, such as members of various hiring, award review, or admission committees, why they are competent teachers deserving of employment, awards/recognition, or admission” (Wang, 2023, p. 1). Writers do this by addressing course design, scholarly teaching, learner-centeredness, and professional development (Simonson, Earl, & Fray, 2021; Taylor & Charlebois, 2024). SoTL offers a lens to writers to communicate their teaching effectiveness to others.

SoTL as the Lens

Despite the lack of consensus in the higher education literature around what constitutes effective teaching (Barbeau & Cornejo Happel, 2023; De Courcy, 2015; Hu, 2020), SoTL offers an answer to documenting effective teaching through examples, a process for determining one’s own teaching effectiveness, and the language to share this effectiveness with others. Using SoTL as the lens to writing and reading a teaching dossier means that our understanding of what SoTL is will be used to engage with, analyze, and evaluate the dossier. When applying a lens to the writing process, the writer will reflect upon their work and elaborate to meet the goals inherent in the lens. It can be a guide to the writer in the revision process by encouraging critical questioning about how the argument made in the work addresses the applied lens. SoTL has been used as the lens in examining academic integrity (Kenny & Eaton, 2022), generative AI (Moya & Eaton, 2023), and professional development in academic librarianship (Mitchell & Mitchell, 2015).

A commonly accepted definition of the SoTL was provided by Potter and Kustra (2011) as “the systematic study of teaching and learning, using established or validated criteria of scholarship, to understand how teaching (beliefs, behaviors, attitudes, and values) can maximize learning, and/or develop a more accurate understanding of learning, resulting in products that are publicly shared for critique and use by an appropriate community” (p. 2). Reflecting on the components of this definition in relation to teaching dossiers reifies the notion that SoTL is an appropriate lens for dossier composition and evaluation.

Systematic study of teaching and learning. In this component, an instructor is urged to intentionally look at their teaching and student’s learning over time in a critical and deliberative manner. As an instructor composes a dossier, a variety of documentary evidence is included with a narrative triangulating this evidence to examine the teaching and learning overall.

Using established or validated criteria of scholarship. The university promotion guidelines (or award guidelines), provide criteria for evaluating teaching and often stipulate certain required documents as evidence. These criteria are typically established through faculty governance or by an awarding entity and informed by the body of literature on teaching and learning.

Understand how teaching can maximize learning. Many dossier reviewers will expect a robust analysis of the writer’s impact on learning. After all, effective teaching ought to maximize learning. The term maximize is crucial. Many methods can lead to documenting impact on learning, but SoTL is differentiated from other forms of educational inquiry by its goal of improving teaching and learning (Potter & Kustra, 2011).

Result in products publicly shared for critique and use by an appropriate community. There are at least three ways that dossiers meet this criterion of SoTL. Simply put, all dossiers result in a product that is publicly shared for critique. The reflection on and development of a dossier connects multiple foundations, sources of criteria, and evidence. These connections create a fertile ground not only for critique and discussion, but also for contributing new ways of knowing and doing for the community of teachers and scholars. Building off the notion of contribution, the teaching-related activities included in a dossier are themselves fertile ground for further study.

Teaching Dossier as SoTL

We argue that the dossier itself is a form of SoTL as it is a publicly disseminated study of teaching excellence which relies on a pre-established methodology for analyzing the dossier writer’s reflective, evidence-based argument for teaching excellence. All SoTL seeks to answer a research question or reflect on a teaching and learning context (Potter & Kustra, 2011): the dossier is no different as it answers the question to what degree does the instructor’s teaching fulfill the criteria set forth in guidelines. Thus, the steps of compiling a quality dossier mirror the SoTL process, beginning with framing the research question, identifying a relevant teaching/learning framework, planning interventions, investigating outcomes, and documenting the work as a form of scholarship shared for peer review and contribution to the institution or entity that considers the dossier (Richlin, 2001).

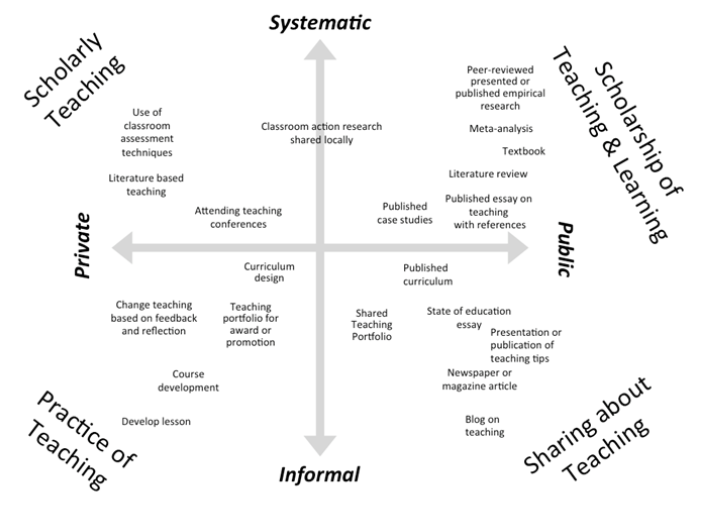

While the guidelines assert the research question and criteria for evaluation, the evidence itself will derive from many aspects of teaching. One model that describes the “dimension and activities related to teaching” (DART) (Kern, Mettetal, Dixon, & Morgan, 2015) identifies products as they individually relate to SoTL. This visual framework places products created through teaching on two axes ranging from private to public and informal to systematic. In the DART model, SoTL falls in the quadrant representing public and systematic work and includes products such as peer reviewed articles and textbooks. Typically, the private, informal products in this framework lack dissemination, formal peer review, or assurance of rigorous methodology. Placement in the dossier, however, should demonstrate rigorous criteria-based reflection as the dossier writer asserts the products are evidence of teaching excellence. And the dissemination of a dossier transforms the private nature of many of the private, informal products as they become publicly shared for peer review.

Figure 1

Dimensions of Activities Related to Teaching (DART Model)

Note: Figure reprinted with permission. Kern, B., Mettetal, G., Dixson, M. D., & Morgan, R. K. (2015). The role of SoTL in the academy: Upon the 25th anniversary of Boyer’s scholarship reconsidered. Journal of the Scholarship for Teaching and Learning, 15(3), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.14434/josotl.v15i3.13623.

Additionally, dossiers often rely on a combination of evidence produced through quantitative and qualitative methodologies with work products in all quadrants of the DART model serving as evidence.

From a genre point of view, the DART model includes dossier sub-genres such as teaching statements, syllabi, and publications. Hyon (2008, p. 179-180) calls work such as a dossier a meta-genre comprised of prior work taking place in other genres. While Hyon includes promotion and tenure reports among these meta-genres, we extend the term meta-genre to the dossier itself, which may include a wide range of sub-genres in response to the guidelines of the entity issuing the criteria.

Application of the SoTL Lens

The following vignettes present concrete applications of the SoTL lens in the context of a faculty member’s dossier for an award and for promotion.

Vignette 1

The Faculty Academy on Excellence in Teaching (FACET) is a faculty-run, grassroots community supporting scholarly teaching across the Indiana University system. Membership in this community is via an application process that is reviewed at both the campus and state level by members of the FACET community. One of the application guidelines ask faculty to document their engagement with student feedback. Meeting the criteria requires the following:

- The applicant clearly describes commitment to ongoing growth in teaching in response to student feedback.

- The evidence strongly supports the conclusion that engagement with student feedback led to the growth described in the statement.

- The documented growth exemplifies the candidate’s teaching philosophy in action.

- The description exemplifies ongoing reflective practice.

(FACET, 2023).

To make a claim that the applicant is committed to learner-centered pedagogy, the applicant may provide a statement that documents a change in teaching based on student feedback. The statement will also be supported by evidence.

For example, the applicant might conduct a narrative analysis of the comments on the end-of-year student evaluations of teaching and discover students felt there was too much reading in the course. They might then talk with the teaching center to learn about the scholarship around appropriate amounts of reading in a course and through use of a course workload estimator tool discover it is not the number of assigned readings, but the density of the readings. They also learn about UDL principles, making sure readings are accessible to all students, and the fact traditional reading is not always necessary. As a result in the next semester, they provide some readings as podcasts, blogs, or other content such as traditional journal articles. At the end of the semester, a review of the student comments indicates the complaints about too much reading are no longer there.

In this example, the statement will describe the specific teaching and learning issue and provide evidence of the need for change, the scholarly basis for the interventions, and outcomes. The reflective statement itself will also be supported with the pre and post reading list as well as pre and post reflections on the student evaluation data.

Vignette 2

The teaching philosophy statement in a promotion dossier will describe and explain elements of the teaching philosophy as they apply to teaching strategies in particular classes and teaching situations. As one writes a teaching statement, the descriptions of successful application of the teaching philosophy in specific classes may take the form of a case study. A case study according to the Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning is described as “a description of the teaching situation or problem, which must be well-grounded in the literature, solution or solutions attempted, quantitative or qualitative analysis of the effectiveness of the solution, reflection on the implications and possible generalization to other settings or populations” (About the Journal, 2025). While the teaching statement is unlikely to contain a full case study, it might include an abstract of a case study describing a teaching situation or problem in their own teaching, the solutions attempted, and a brief summary of the quantitative or qualitative analysis of the effectiveness of the solution. The teaching statement might also reflect on the implications of the solutions across courses the instructor has taught.

Vignette 3

As instructors respond to teaching and learning situations, their interventions often lead to new teaching materials, assessments, and learning resources and activities. The SoTL lens promotes an evidence-based approach to decisions about new interventions or course materials. Consider the mix of diagnostic, formative, and summative assessments to track student growth. The data these assessments produce allow the instructor to view the course through the lens of a researcher, analyzing data, and supporting course evolutions.

Conclusion

By presenting SoTL as a lens through which to engage with the teaching dossier, we offer readers a theoretical framework in which to situate other chapters in this volume. Many of the artifacts used to demonstrate teaching excellence (teaching philosophy statements, end of course evaluations, peer teaching observations, examples of student assessment, professional development activities, and more) become part of the dossier. SoTL offers individual faculty a lens through which these individual pieces of evidence can be synthesized into a compelling argument.

Consider telling your dean you have a teaching problem, or students are having a problem learning in your course. Likely, this elicited anxiety or similar negative reaction. Now consider telling your dean about the problem you’re currently addressing in your scholarship. In the first instance, a problem is not welcome while in the second, the problem is the lifeblood of the activity (Bass, 1998). By taking a systematic approach to understanding teaching, you are able to positively and more accurately understand how the choices you make as the instructor can impact learning on the part of the students.

By taking this same approach when evaluating an instructor’s teaching, the resulting conversations take on an air of continuous improvement and growth as a scholarly teacher rather than a remedial or punitive nature. Does the narrative and accompanying artifacts included in the teaching dossier, demonstrate the instructor approached their teaching over the course of their review period systematically, using established or validated criteria of pedagogical scholarship, to understand how their teaching maximized learning for their students?

References

About the Journal. (n.d.). Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. Retrieved May 14, 2025 from https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/josotl/about

American Council on Education [ACE], The American Association of University Professors [AAUP], & United Educators (2000). Good practice in tenure evaluation. Advice for tenured faculty, department chairs, and academic administrators. https://www.aaup.org/sites/default/files/files/Good%20Practice%20in%20Tenure%20Evaluation.pdf

Andrews, J. G. (2009, January – February). On extending the probationary period. Academe. https://www.aaup.org/article/extending-probationary-period

Auken, S. (2020). On genre as social action: Uptake, and modest grand theory. Discourse and Writing/Rédactologie, 30(1), 161-171. https://doi.org/ 10.31468/cjsdwr.823

Barbeau, L. & Cornejo Happel, C. (2023). Critical Teaching Behaviors: Defining, Documenting, and Discussing Good Teaching. New York: Routledge.

Bass, R. (1999). The scholarship of teaching: What’s the problem? Inventio: Creative Thinking about Learning and Teaching, 1(1), 1–10.

Berk, R. A. (2018). Start spreading the news: Use multiple sources of evidence to evaluate teaching. Journal of Faculty Development, 32(1), 73-81.

Bernstein, D. J. (2008). Peer review and evaluation of the intellectual work of teaching. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 40(2), 48–51. https://doi.org/10.3200/CHNG.40.2.48-51

Brookfield, S. (1995). Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher. San-Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Casal, J. E., & Kessler, M. (2020). Form and rhetorical function of phrase-frames in promotional writing: A corpus- and genre-based analysis. System, 95:102370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102370

Cohen, J. (2003). Documenting teaching excellence within the peer review of teaching. Journalism and Mass Communication Educator, 58(2), 115-118.

De Courcy, E. (2015). Defining and measuring teaching excellence in higher education in the 21st century. College Quarterly, 18(1).

Delgadillo, L. M. (2019). Documenting teaching excellence for tenure- and non-tenure-track positions in family and consumer sciences. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 47(4), 303-421. https://doi.org /10.1111/fcsr.12311

FACET. (2023). FACET nominee review form. https://facet.iu.edu/doc/FACET-Nominee-Review-Form-2023

FACET. (2025). Strategic plan. https://facet.iu.edu/about_us/strategic-plan.html

Hu, C. C. (2020). Understanding college students’ perceptions of effective teaching. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 32(2), 318-328.

Hyon, S. (2008). Convention and inventiveness in an occluded academic genre: A case study of retention – promotion – tenure reports. English for Specific Purposes, 27, 175-192.

Indiana University (2024). Guidelines for promotion reviews for instructional ranks at Indiana University – Bloomington. https://vpfaa.indiana.edu/doc/instructional-ranks-promotion-guidelines_2024.11.07-for-posting.pdf

Kenny, N., Eaton, S.E. (2022). Academic Integrity Through a SoTL Lens and 4M Framework: An Institutional Self-Study. In: Eaton, S.E., Christensen Hughes, J. (eds) Academic Integrity in Canada. Ethics and Integrity in Educational Contexts, vol 1. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83255-1_30

Kern, B., Mettetal, G., Dixson, M. D., & Morgan, R. K. (2015). The role of SoTL in the academy: Upon the 25th anniversary of Boyer’s scholarship reconsidered. Journal of the Scholarship for Teaching and Learning, 15(3), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.14434/josotl.v15i3.13623

Miller, C. R. (1984). Genre as social action. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 70(2), 151–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/00335638409383686

Miller, S. (2023). A review of U.S. tenure and promotion guidelines in media and communication and their support for engaged scholarship. Communication Education, 72(1), 96–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2022.2137217

Mitchell, L. N. & Mitchell, E. T. (2015) Using SoTL as a lens to reflect and explore for innovation in education and librarianship. Technical Services Quarterly, 32(1), 46-58. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/07317131.2015.972876

Moya, B.A., & Eaton, S.E. (2023). Examining recommendations for artificial intelligence use with integrity from a scholarship of teaching and learning lens. RELIEVE, 29(2), art. M1. http://doi.org/10.30827/relieve.v29i2.29295

Osman, H. (2006). Communicative functions of a promotional genre as a social action. Journal of Language Studies, 2, 111-123.

Potter, M. K. & Kustra, E. D. H. (2011). The relationship between scholarly teaching and SoTL: Models, distinctions, and clarifications. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 5(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2011.050123

Prescott, Jr., W. A. (2023). Reviewing promotion dossiers as a professional responsibility. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 87(11). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpe.2023.100574

Richlin, L. (2001). Scholarly teaching and the scholarship of teaching. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 86. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Russell, D.R. (2023). Motivation and genre as social action: A phenomenological perspective on academic writing. Frontiers in Psychology, 14:1226571. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1226571

Simonson, S. R., Earl, B., & Frary, M. (2021). Establishing a framework for assessing teaching effectiveness. College Teaching, 70(2), 164–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2021.1909528

Taylor, S., & Charlebois, S. (2024). Teaching dossier guidance for professional faculty: An evidence-based approach for demonstrating teaching effectiveness. Frontiers in Education, 9:1284726. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1284726

University of Houston. (2022). General guidelines for NTT promotion review. https://www.uh.edu/provost/faculty/policies-and-procedures/faculty-policies/non-tenure-track/documents/2022-2023-general-guidelines-for-ntt-promotion-review.pdf

Wang, Y. A. (2023). Demystifying academic promotional genre: A rhetorical move-step analysis of teaching philosophy statements (TPSs). Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 65:101284.