13 Mentorship matters: Documenting the unseen impact of instructor-student relationships

Jeff Spears; Amanda Deliman; Hannah Lewis; Jim LaMuth; and Kim Hales

Introduction

This chapter explores the critical yet often unrecognized role of documenting instructor mentorship as a core component of teaching excellence in higher education. Mentorship encompasses a range of instructor-to-student interactions, including academic guidance, psychosocial support, research support (graduate and undergraduate), and career exploration for students (DeAngelo, Mason, & Winters, 2016; Thiry & Laursen, 2011). Despite its importance, mentorship is rarely documented comprehensively in teaching documentation portfolios (Ocobock et al., 2022). By systematically capturing the multifaceted impacts of mentorship, instructors enhance their teaching portfolio and contribute to the broader discourse on teaching excellence. This chapter aims to empower instructors to demonstrate how mentorship serves as a key element of their educational contributions. The strategies offered are drawn from real-world examples, including dossiers submitted by faculty members in Utah State University’s Faculty-to-Student Mentorship Program. These contributors are deeply involved in guiding students and serve on the steering committee for the mentorship program.

These perspectives on mentorship are informed by their lived experiences as educators, mentors, and researchers within higher education. Having served as program directors and faculty members across a variety of institutional roles, including steering committee members for Utah State University’s mentorship initiative, we draw on both qualitative reflections and institutional data to advocate for the meaningful integration of mentorship into teaching documentation. Our backgrounds in social work, teacher education, social sciences, and student engagement shape the lens through which we evaluate mentorship as a facet of teaching excellence.

At most universities, mentorship is encompassed by teaching requirements for the purpose of promotion to demonstrate teaching excellence. To support instructors in their efforts, this chapter provides practical strategies for capturing mentorship outcomes. We consider the value of mentorship within the context of teaching excellence, discussing how it supports students’ academic success, emotional resilience, and career readiness. We also use the Ragins and Scandura (1999) dimensions model to explore methods for documenting these mentorship impacts, including the use of student testimonials, tracking mentee achievements, and reflecting on mentorship practices. Through this approach, instructors can effectively showcase how mentorship is integral to their educational contributions, fostering a richer understanding of teaching excellence beyond classroom instruction.

Literature review

Definition of Mentorship and Impact

Through an extensive literature review, Utah State University’s Statewide Faculty-to-Student mentorship program was built on an operational definition of mentorship, grounded in a theoretical framework and supported by a rigorous methodology (Law et al., 2021). Most mentorship programs lack a clear definition of mentorship rooted in literature (Law et al, 2021 Nora and Crisp (2007) identify four cornerstones of mentorship in a teaching capacity: (a) psychological/emotional support, (b) goal setting and career paths, (c) academic subject knowledge support, and (d) role modeling. Each of these constructs establishes an operational definition of mentorship on a collegiate level (Law et al., 2020). Therefore, the mentorship program at USU defined mentoring as building purposeful and personal relationships in which a more experienced person provides guidance, feedback, and support to facilitate the growth and development of a less experienced person (Law et al., 2021).

Recognizing the critical role of mentorship, instructor engagement significantly enhances students’ sense of belonging within the university (Phinney et al., 2011). A student is more likely to engage in research, experience hands-on learning, and eventually engage as a mentor in their own careers by participating in professional mentorship (Gürtunca, 2024). Mentors possess the ability to instill career role modeling (Raposa et al., 202; Hagler, 2018) and psychosocial behavior deemed appropriate in professional settings (Nadder, 2024).

Mentorship is Teaching Excellence

Mentorship is traditionally part of the role statement for instructors, where it often remains an implicit expectation rather than a formally recognized responsibility (Gürtunca, 2024). Colleges that focus on mentoring as part of the tenure process provide essential training and ways to craft promotion materials (Etzkorn & Braddock, 2020). These universities believe mentorship is vital to teaching excellence (Kaplan & Mills, 2024). Teaching excellence consists of several attributes required of an instructor, including professional industry connections, research, leadership, and institutional rankings (Bweupe & Mwanza, 2022). Most universities leverage instructor mentoring programs as a method to enhance student-to-work transitions into career exploration, explore research, and sharpen pedagogical approaches to teaching philosophies (Nabi et al., 2024).

Furthermore, an undergraduate researcher engaging in refereed presentations or symposiums enhances their communication skills development, which in turn leads to an increase in their science identity, research self-efficacy, and sense of belonging to a field of study (Corwin et al., 2015; Fakayode et al., 2014; Robnett et al., 2015). Students in STEM majors often learn the academic path for acceptance into graduate and health professional programs from their mentors (Daniels et al., 2019). In majors where the requirements for graduate school are more strenuous than just academic achievements, mentors can assist in career exploration, foster discussions of volunteer opportunities, facilitate crafting competitive applications, and frame leadership roles/research during undergrad (Zentgraf, 2022). The literature clearly articulates the benefits of mentoring, yet it fails to highlight ways of documenting it for promotion and career development.

There is little evidence in the literature educating instructors on how to document mentorship in promotional materials and articulating a compelling story of student development (Aderibigbe, Gray, & Colucci-Gray, 2018; Mena et al., 2016). Most instructor mentorship programs require a paradigm shift from a theory focus to a hands-on approach to student support, which is not part of most graduate training programs (Rehman et al., 2024). At USU, documentation is a form of storytelling and must be communicated in a way understandable by outside professionals (Galey et al., 2019). In the following section, the statewide mentorship program at USU will be reviewed for the benefits of student mentoring and suggestions for incorporating storytelling in promotional packets.

Testing the Construct: Mentoring Benefits of Mentors

Ragins and Scandura (1999) developed and tested several dimensions related to the costs and benefits of being a mentor. Their instrument tested two benefits of mentoring: rewarding experience and improving job performance. Their initial work and instrument focused on mentoring in a professional setting, querying high-level managers and executives, not instructors in academia. USU’s Statewide Faculty-to-Student mentoring program uses four of Ragins and Scandura’s dimensions in their end-of-semester post-assessments as part of a 6-year study of how mentoring can impact students and instructors. A research protocol for collecting and analyzing these assessments of the mentorship program was approved by USU’s Institutional Review Board. The results discussed below represent aggregate data. Table 1 depicts the four expected benefits from Ragins and Scandura’s instrument that align with the values discussed in this chapter.

Table 1

Ragins and Scandura’s Instrument Dimensions

|

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements. Strongly Disagree Somewhat Disagree Neither Disagree nor Agree (Neutral) Somewhat Agree Strongly Agree

|

|

Dimension: Rewarding Experience Question 1: One’s creativity increases when mentoring others

|

|

Dimension: Improved Job Performance Question 2: Mentoring has a positive impact on the mentor’s job Question 3: Mentoring is a catalyst for innovation Question 4: Mentoring has a positive impact on the mentor’s job performance

|

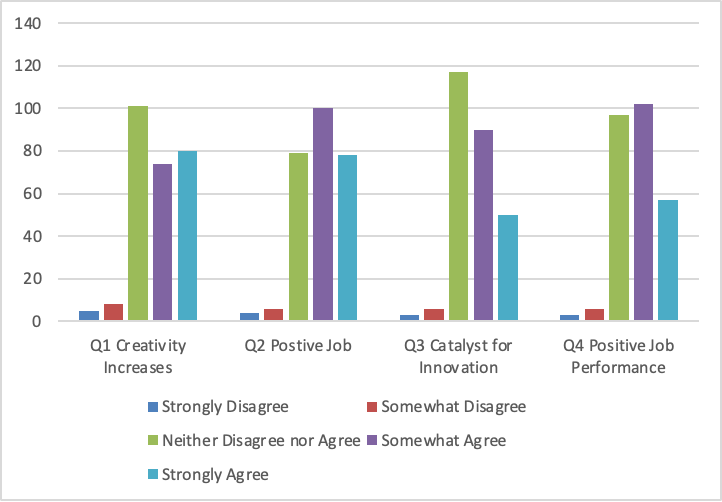

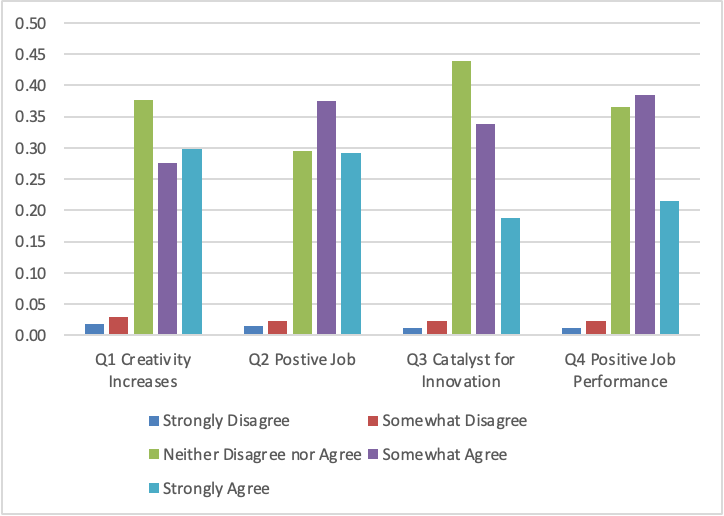

At the end of each semester, instructors were asked to respond to Likert scale questions ranging from 1-Strongly Disagree to 5-Strongly Agree. Between Fall 2020 and Spring 2024, between 23 to 54 mentors participated in the research component of the program each semester. Response rates for the post-semester assessments ranged from 64.7% to 100%. At an alpha level of 0.01, the p-values for all four questions are less than the significance threshold, leading us to reject the null hypothesis that all were equally likely to be chosen, in each case. Therefore, we conclude that statistically significant evidence suggests that the responses to these questions were not evenly distributed across the five options. All the bar charts are skewed left with higher values from Neutral to Strongly Agree as seen in Figure 1 and Figure 2. Based on these results we conclude that mentoring is having a positive impact on instructors in these dimensions of interest. The detailed results for the Chi-Square test are included in the Appendix.

Figure 1

Responses from Instructors Given in Actual Count Over Four Years

Figure 2

Responses from Instructors Given as Proportions Over Four Years

Translating Mentorship into Documentation

The above data indicates the success of the mentorship program at USU from the perspective of the instructors. In most programs, success is based on the responses from students, yet instructors are just as invested in the process. However, much like the literature suggests, instructors are left with little guidance to tell the story of their efforts for promotion and tenure. Based on our work in the statewide mentorship program at USU, we offer the following strategies to document mentorship as teaching excellence:

Student Testimonials. Testimonials offer a student perspective on the impact of customized mentorship (Morales et al., 2017). Each student has different needs, and mentors will vary in their approach to mentorship. Regardless of circumstance, students benefit from being mentored by instructors who have experienced the ups and downs of higher education and forged professional, community, and college resource connections (Guzzardo et al., 2021). The narrative of the student experience can be a point of emphasis in promotion and tenure materials. These letters of support regarding mentorship can range from college retention/graduation efforts, research endeavors, graduate letters of recommendation, and application of lessons from class in professional settings.

Instructors can request testimonials from students to include in their teaching materials. As part of best practice, the authors recommend that the student has completed the class and that grades have been submitted. Mentors can also reflect on how mentorship has improved their teaching excellence. The definition of teaching excellence (Bweupe & Mwanza, 2022) would encourage instructors to consider connecting the student to academic/professional support, guiding research projects, and exploring their leadership abilities. At most institutions, mentorship is categorized as part of teaching but is not required for promotion and tenure.

Student-Directed Projects. Instructors mentorship is crucial to the development and oversight of student research (Vela et al., 2024). Instructors can offer guidance through the IRB process, project conceptualization, and result interpretations (Nolan et al., 2020). In documentation, instructors should discuss how student research connects to their teaching philosophy. In some cases, course content might be incorporated into student research. The best advice for instructors is to intertwine teaching in the classroom with research goals.

For some student-directed projects, the instructor is more of an advisor to the student project and provides guidance. This would include honors projects, mentored projects, and lab mentorship in the sciences. These projects could be displayed in the teaching portfolio as a table with reflection prompts of student development.

One of the potential benefits of student research is publications and presentations. Instructor mentors should document presentations/articles on their CV. In the evaluation process, these student works will allow for a chance to highlight real-world changes stemming from research. Coupled with student testimonies/letter of support for mentoring efforts, the two strategies will provide ample opportunities to discuss the impact on teaching excellence.

Mentor/Mentee Publication Tabulations. In teaching documentation, instructors complete a section on teaching improvement. The topics can range from changes in the classroom to mentorship opportunities. Most instructor mentors create a table with the students mentored, year, name of the research, and format – publication, presentation, and posters (Phillips & Dennison, 2023). Instructors should also include PowerPoints of presentations to provide more content for the reader. We also suggest that a reflection be included on how the mentorship project impacted their teaching and supplemented their research agendas. Table 2 is an example of displaying an instructor presentations/publications in teaching documentation:

Table 2

Sponsored Student Presentations/Articles

|

Student(s) |

Year |

Presentation/Article |

Name of Conference (Local, State, National, International) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Number of Mentees. Instructors can count how many mentees they guided over the course of the academic year. These numbers can quantify the time spent outside the classroom or advising sessions (Hart-Baldridge, 2020). In certain role statements, program-specific advising is left to the instructors once a student matriculates into the course of study under the direction of the mentor. In Table 3, instructors are encouraged to track not only mentorship but also the services provided to the students, discussed below.

Table 3

Instances of Student Mentorship

|

Student(s) |

Year |

Type of Mentorship |

Goal of Mentee/Result |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mentees Goal Setting. Since mentoring meetings happen monthly at USU, instructors and students are encouraged to develop goals for academic and career achievements. The instructor can document these goals. In fact, students who create goals based on mentorship are more likely to achieve milestones (van Lent & Souverijn, 2020). Students should establish short-term tasks – for example, excellent grades in classes and passing the first semester of college. These goals allow students not only to develop confidence but also to scaffold into larger, more complex goals, such as job preparation and critical thinking skills (Greco & Kraimer, 2020).

Narrative Reflections. The above suggestions provide instructors with the opportunity to explain the impact of mentoring a student to meet certain professional markers. Whether the student is working on short- or long-term goals, the instructor can reflect on how their involvement/skill set was instrumental to student development. Moreover, describing this development provides an opportunity for instructors to refer to presentations, papers, and other scholarly work in their dossier.

Challenges

Teaching excellence involves more than just effective classroom pedagogy; it includes providing meaningful mentorship opportunities to students. This section will focus on some challenges with documenting mentorship and suggestions for possible solutions. First, instructors who perceive mentorship as time-consuming may opt out of even the most successful programs (Faulconer et al., 2020). This is especially true for instructors who lack an understanding of how mentoring is part of their teaching excellence. Colleges with student mentorship programs are another factor for instructors participating in mentorship (Phillips & Dennison, 2023). For example, at USU, mentorship is part of the role statement for instructors and is highly encouraged by the administration to bolster graduation and retention rates.

Second, mentees who are not adequately prepared for the mentoring experience are a common challenge in all forms of mentoring; mentors indicate that mentees often lack training and understanding of the program goals and expectations (Ehrick et al., 2004). Mentors expect mentees to be engaged and reliable and value their time and commitment (Obobock et al., 2021). Productive and purposeful mentoring conversations require mentees to establish objectives and meet the standards outlined early in mentor pairing; creating an environment for helpful learning dialogues varies from the informal conversations that mentees may be accustomed to (Mullen & Klimaitis, 2019). Formalized training for mentees and mentors may help mitigate these challenges by focusing on the importance of goal setting and understanding the program’s intended purpose.

Third, in all the requirements for instructors, the ability to document milestones or achievements might be difficult to manage over the course of a career. Most instructors meet with their students monthly and never think about documenting the mentoring opportunity. Instructors write several letters of recommendation as support without tallying how many were written throughout their career.

Lastly, mentorship is a skill typically not part of a curriculum in graduate school. In most advanced career disciplines, content in curriculum development tends to dominate the training of future instructors (Phillips & Dennison, 2023). As they become teachers, they may not know how to provide resources for their students, provide research mentorship, and prioritize student growth outside the classroom. This chapter recommends certain strategies for instructors to document teaching excellence. Documentation is critical to not only promotion/tenure but also reflecting on meaningful work with students. Table 4 addresses some of the common challenges facing college instructors and possible suggestions to engage in student mentoring.

Table 4

Addressing the Concerns of Student Mentoring

|

Challenge(s) |

Suggestion |

|

Time-consuming |

Set boundaries (Only mentor a few students) Encourage administration to count mentorship in teaching statements through documentation. |

|

Students lack interest in mentoring. |

Review your research/work in class to spark discussion Discuss the importance of course material in career/graduate school Offer mentorship as an option with specific examples – presentation opportunities or publications |

|

Difficulty in documenting mentorship |

Keep a journal of mentoring activities Add accomplishments to CV Track the letters of reference each year

|

|

Lack skills/training for mentoring |

Start with students in class or advising requirements Attend workshops/conferences on mentoring Discuss importance of mentoring students with department head/dean |

Conclusion

Documenting mentorship as an integral dimension of teaching excellence offers many benefits- not only for individual instructors but also for students and the institution. By acknowledging mentorship in teaching documentation, we validate its profound impact on student success, foster a culture of professional growth, and elevate mentorship as a critical component of academic excellence. This chapter’s detailed overview of mentorship documentation methods, from direct evidence of student achievements to incorporating reflection narratives, demonstrates how instructors can make mentorship a documented, measurable aspect of their roles. Through examples from Utah State University’s program, readers can see how these strategies translate to tangible outcomes, such as improved retention rates and strengthened student engagement. Recognizing mentorship as a fundamental aspect of teaching excellence aligns with the university’s mission to promote holistic student development and helps instructors convey the full scope of their contributions to the academic community. As higher education continues to evolve, systematic documentation of mentorship will be essential for honoring these contributions and reinforcing the integral role of mentorship in teaching excellence.

References

Aderibigbe, S., Gray, D. S., & Colucci-Gray, L. (2018). Understanding the nature of mentoring experiences between teachers and student teachers. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 7(1), 54-71.

Bweupe, B. S., & Mwanza, J. (2022). No one has bothered to know: Understanding the constructions of teaching excellence in higher education institutions of Zambia: A Hermeneutic Phenomenological Approach. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 10(9), 87-114. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2022.109007

Corwin, L. A., Graham, M. J., & Dolan, E. L. (2015). Modeling course-based undergraduate research experiences: An agenda for future research and evaluation, CBE—Life Sciences Education, 14(1), 1–13. https://doi. org/10.1187/cbe.14-10-0167.

DeAngelo, L., Mason, J., & Winters, D. (2015, November 7). Faculty engagement in mentoring undergraduate students: How institutional environments regulate and promote extra-role behavior. Innovative Higher Education, 41, 317-332. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10755-015-9350-7

Daniels, H. A., Grineski, S. E., Collins, T. W., & Frederick, A. H. (2019). Navigating social relationships with mentors and peers: Comfort and belonging among men and women in STEM summer research programs. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 18(2), ar17 https://www.lifescied.org/doi/pdf/10.1187/cbe.18-08-0150

Ehrich, L. C., Hansford, B., & Tennent, L. (2004). Formal mentoring programs in education and other professions: A review of the literature. Educational Administration Quarterly, 40(4), 518-540. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X04267118

Etzkorn, K. B., & Braddock, A. (2020). Are you my mentor? A study of faculty mentoring relationships in US higher education and the implications for tenure. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 9(3), 221-237. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMCE-08-2019-0083

Fakayode, S. O., Yakubu, M., Adeyeye, O. M., Pollard, D. A., & Mohammed, A. K. (2014). Promoting undergraduate STEM education at a historically Black college and university through research experience. Journal of Chemical Education, 91(5), 662–665. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/ed400482b

Faulconer, E. K., Dixon, Z., Griffith, J., & Faulconer, L. (2020). Perspectives on undergraduate research mentorship: A comparative analysis between online and traditional faculty. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 23(2), 1.

Galey, F., Read, S., Spicer-Escalante, M. L., Bullock, C. F., Blackstock, A., Bernal, S., … & Lott, K. H. (2019). USU Teaching Documentation: Dossiers from the Mentoring Program. Utah State University.

Greco, L. M., & Kraimer, M. L. (2020). Goal-setting in the career management process: An identity theory perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000424

Gürtunca, B. (2024). The role and the effectiveness of the mentorship in education: the effect and the importance of the mentors in forming the careers and psychosocial functions of teachers. Journal of Innovation Transformation and Development Research, 1(1).

Guzzardo, M. T., Khosla, N., Adams, A. L., Bussmann, J. D., Engelman, A., Ingraham, N., … & Taylor, S. (2021). “The ones that care make all the difference”: Perspectives on student-faculty relationships. Innovative Higher Education, 46, 41-58.

Hagler, M.A. (2018). Processes of natural mentoring that promote underrepresented students’ educational attainment: a theoretical model. American Journal of Community Psychology, 62(1-2) 150– 162.

Hart-Baldridge, E. (2020). Faculty advisor perspectives of academic advising. NACADA Journal, 40(1), 10-22.

Kaplan, B. B., & Millis, B. J. (1995). No sticks, just carrots: Soliciting teaching portfolios from teaching excellence award nominees. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 6(1)

Law, D., Hales, K., & Busenbark, D. (2020). Student success: A literature review of faculty to student mentoring. Journal on Empowering Teaching Excellence, 4(1), 22-39.

Law, D., Busenbark, D., Hales, K. K., Taylor, J. Y., Spears, J., Harris, A., & Lewis, H. M. (2021). Designing and implementing a land-grant faculty-to-student mentoring program: Addressing shortcomings in academic mentoring. Journal on Empowering Teaching Excellence, 5(2), 27-45.

Morales, A.W., Agili, S. S., Vidalis, S. M., Null, L. M., & Sliko, J. L. (2017). The role of customized mentoring in a successful STEM scholarship program for underrepresented groups. In American Society for Engineering Education (ASEE), Proceedings of the 124th ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition. Columbus, OH: United States

Mena, J., García, M., Clarke, A., & Barkatsas, A. (2016). An analysis of three different approaches to student teacher mentoring and their impact on knowledge generation in practicum settings. European Journal of Teacher Education, 39(1), 53-76.

Mullen, C.A., & Klimaitis, C.C. (2021), Defining mentoring: a literature review of issues, types, and applications. Annuals of the New York Academy Sciences, 1483, 19-35. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.14176

Nabi, G., Walmsley, A., Mir, M., & Osman, S. (2024). The impact of mentoring in higher education on student career development: A systematic review and research agenda. Studies in Higher Education, 50(4), 1-17.

Nolan, J. R., McConville, K. S., Addona, V., Tintle, N. L., & Pearl, D. K. (2020). Mentoring undergraduate research in statistics: Reaping the benefits and overcoming the barriers. Journal of Statistics Education, 28(2), 140-153.

Ocobock, C., Niclou, A., Loewen, T., Arslanian, K., Gibson, R., & Valeggia, C. (2022). Demystifying mentorship: Tips for successfully navigating the mentor–mentee journey. American Journal of Human Biology, 34, e23690.

Nadder, H. M. (2024). Nurse faculty mentoring of students to optimize student success: A basic qualitative study. Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 20(1), e27-e33.

Phillips, S. L., & Dennison, S. T. (2023). Faculty mentoring: A practical manual for mentors, mentees, administrators, and faculty developers. Taylor & Francis.

Phinney, J. S., Torres Campos, C. M., Padilla Kallemeyn, D. M., & Kim, C. (2011). Processes and outcomes of a mentoring program for Latino college freshmen. Journal of Social Issues, 67(3), 599–621. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2011.01716.x

Raposa, E. B., Hagler, M., Liu, D., & Rhodes, J. E. (2021). Predictors of close faculty-student relationships and mentorship in higher education: Findings from the Gallup− Purdue Index. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1483(1), 36-49.

Rehman, R., Arooj, M., Ali, R., Ali, T. S., Javed, K., & Chaudhry, S. (2024). Building stronger foundations: Exploring a collaborative faculty mentoring workshop for in-depth growth. BMC Medical Education, 24(1), 797.

Ragins, B. R., & Scandura, T. A. (1999). Burden or blessing? Expected costs and benefits of being a mentor. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20(4), 493–509.

Robnett, R. D., Chemers, M. M., & Zurbriggen, E. L. (2015). Longitudinal associations among undergraduates’ research experience, self-efficacy, and identity. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 52(6), 847–867.

Thiry, H., & Laursen, S. L. (2011). The role of student-advisor interactions in apprenticing undergraduate researchers into a scientific community of practice. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 20(6), 771–784.

van Lent, M., & Souverijn, M. (2020). Goal setting and raising the bar: A field experiment. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 87, 101570.

Vela, J. C., Abrego, M., Rodriguez, A. D., Ramos, D., & Guerra, B. (2024). Exploring the experiences of faculty mentors and graduate research assistants in a college of education at an HSI. Journal of Latinos and Education, 23(3), 997-1016

Zentgraf, L. L. (2020). Mentoring reality: From concepts and theory to real expertise and the mentor’s point of view. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 9(4), 427-443.

Appendix

At the end of each semester, instructors were asked to respond to Likert scale questions ranging from 1-Strongly Disagree to 5-Strongly Agree. Under the null hypothesis that instructors are equally likely to select any of the five options, we conducted Chi-square goodness-of-fit tests for four questions related to instructors’ perceptions. The detailed results are as follows:

- For Question 1, the Chi-square value was 145.545, with a p-value of 0.0000

- For Question 2, the Chi-square value was 152.045, with a p-value of 0.0000

- For Question 3, the Chi-square value was 191.406, with a p-value of 0.0000

- For Question 4, the Chi-square value was 171.981, with a p-value of 0.0000

At an alpha level of 0.01, the p-values for all four questions are less than the significance threshold, leading us to reject the null hypothesis in each case. Therefore, we conclude that statistically significant evidence suggests that the responses to these questions were not evenly distributed across the five options. Based on these results we conclude that mentoring is having a positive impact on instructors in these dimensions of interest.