7 One institution’s journey toward redefining and more holistically assessing teaching effectiveness

Bethany B. Stone; Casandra E Harper; Stephen A. Klien; and Victoria Mondelli

Faculty voice, administrator frustration, low student response rates, and stalled reform efforts to enact substantive changes to how the University of Missouri (MU) evaluated teaching fueled the desire on campus to find a better way. In 2019, MU began a journey away from an overemphasis of a single item on student course evaluations to a constituent-informed, evidence-based, multi-measure system to evaluate and document teaching quality. By sparking a campus-wide conversation and initiative, a new model of effective and inclusive teaching was created that led to new instruments, all aligned to a framework that is proving useful in our overall mission to continuously reflect on and improve teaching for improved student learning (MU Teaching for Learning Center, 2024). As with all major campus transformations, change is slow and as some tensions are resolved, new ones emerge. MU’s journey may hearten readers at the outset of their own journey to transform how teaching is evaluated. We hope this chapter is useful to you in describing our process so that it can be applied in your context. Our inclusive efforts were recognized through the MU Shared Governance Award in 2021, celebrating a collaborative participatory approach for one of the most essential facets of the academy: teaching quality for student learning. The MU model is licensed with a Creative Commons license so that others can reuse, remix, and/or revise it to come alive for different campus contexts.

Before the Task Force to Enhance Learning and Teaching (TFELT), made up of instructors and a few administrators from across campus, was convened jointly by the Office of the Provost and Faculty Council, the Director of the Teaching for Learning Center (one of the co-authors of this chapter) was tasked to gather the literature, review past task force recommendations (from university and system-level task forces), and learn from peers engaging in similar work. Culling resources, learning from models collected by the American Association of Universities (AAU), and visiting colleagues around the country was invaluable in laying the groundwork of a successful process for TFELT. Our annual teaching conference (May 2019) brought national leaders in this work to engage with faculty and encourage the effort: Carl Weiman (Stanford University), Emily Miller (AAU), Ginger Clark (University of Southern California), and others. Based on advice from these national leaders, throughout the entire process we sought input broadly from the MU community including undergraduate and graduate students, instructors, staff, and administrators to reflect the diverse MU perspectives and reflect our campus’s values and priorities. Over the two-year process, TFELT hosted 23 advertised community sessions to encourage feedback from university members during all stages of the project. Encouraging broad participation from across campus both built awareness and provided feedback along the way, which strengthened the quality of the work.

Defining effective teaching and creating the model

Having received its charge, TFELT enacted a process of collaborative inquiry to define teaching quality. The MU Teaching for Learning Center (T4LC) provided key support to TFELT, including providing resources, assisting with communication, and recruiting community members. In addition to the staff of the T4LC, four faculty fellows were onboarded to aid with the research, resource development, planning, and, later, training and implementation.

This body knew the importance of each word and took great care in not only defining quality teaching, but also bringing our campus values, especially inclusivity, to the fore. For example, rather than “Teaching Excellence,” TFELT aimed to evaluate “Inclusive and Effective Teaching” at MU. The group moved forward with the conviction that before you can make tools, you need to articulate what you want to measure. TFELT’s first steps were to 1) define what effective teaching looked like at MU and 2) identify key dimensions that represent that definition. With those goals in mind, TFELT sought out broad representation among the campus community to help construct a common definition of effective teaching. In this section, we describe our process for creating this model.

To define effective teaching at MU, TFELT and the T4LC support team designed community engagement activities to capture, categorize, and test ideas. Open invitations were sent out to all members of campus. TFELT also recruited undergraduate and graduate students, instructors, staff, and administrators. Each demographic provided an important viewpoint to the activities as we worked to shape our definition and model. The result of the first round of community sessions produced artifacts that TFELT could reference as they scripted the following campus definition of Inclusive and Effective Teaching:

At the University of Missouri, effective and inclusive teaching fosters student learning through evidence-based, relevant, organized, and engaging instruction. Effective educators promote diversity by creating inclusive and equitable learning environments with instruction that is student focused. Sustained teaching effectiveness requires continual refinement through deliberate reflection and professional development, and it is supported by institutional resources and programs.

Four Dimensions of Inclusive and Effective Teaching

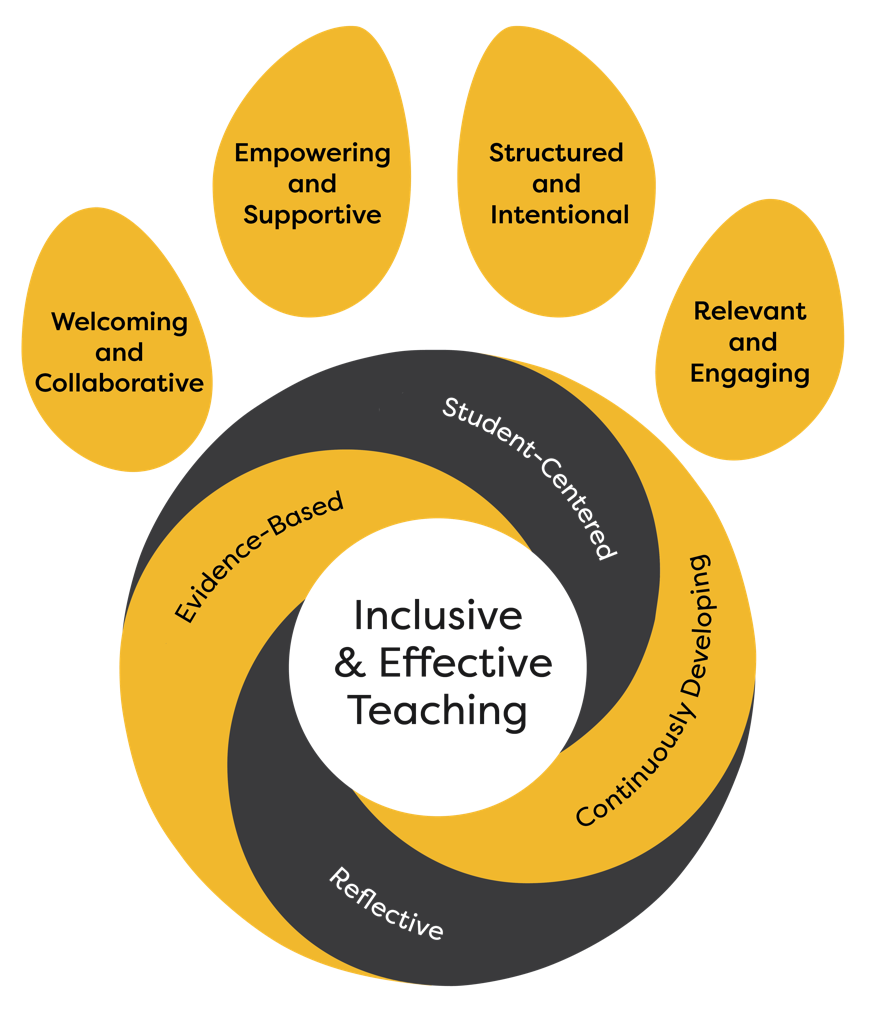

In addition to the definition above, insights drawn from the literature on effective teaching and shared within the university engagement sessions also contributed to the creation of a working model (Figure 1). Teaching practices that rose to the top during the community engagement discussions divided into four dimensions (i.e., observable elements seen by students) and four foundations (i.e., key practices for faculty that might go unseen by students). These proved helpful in scaffolding the assessment tools, such as the self-reflection, peer review rubric, and the student feedback forms. These dimensions and foundations would also be used to organize future professional development opportunities.

Figure 1

University of Missouri Model of Inclusive and Effective Teaching

Note. The “toes” of the pawprint design display the four dimensions of Inclusive & Effective Teaching. The four items in the center of the “paw” are the foundations of Inclusive & Effective Teaching.

The four Dimensions of Inclusive and Effective Teaching, summarized in Table 1, included observable elements of inclusive and effective learning environment. One important discussion was that effective teaching is inclusive teaching that supports a diversity of backgrounds and perspectives. TFELT considered using Inclusive, Diverse, and Equitable Instruction as a fifth dimension. Ultimately, they decided that inclusive teaching practices are key to the success of the other four dimensions and should be reflected throughout the model. They prioritized featuring its integration in the definition and model, as well as throughout the tools and processes used to evaluate teaching. Based on the community conversations and review of the literature, TFELT identified the following Dimensions (TFELT, 2021):

- Welcoming and Collaborative – The instructor welcomes and actively includes all students and perspectives in the learning environment. Students in the course collaborate with the instructor and other students (Deslauriers, 2019). Key related terms: inclusive, interactive, dialogue, creative, relationships, respectful.

- Empowering and Supportive – The instructor invites students to set and reach their learning goals. The instructor supports student success through giving constructive feedback, mentoring, advising, and guiding students while listening and responding to student needs (Cavanagh, 2016). Key related terms: professional, encouraging, inspiring student action, approachable.

- Structured and Intentional – The instructor plans the course well, describes the course clearly, and aligns learning objectives, learning activities, and assessment. The instructor clearly communicates these expectations and what students need to do to meet them. Key related terms: clear communication, outcome based, high standards, accessible, scaffolded (Ambrose et al., 2010).

- Relevant and Engaging – The instructor helps students discover the relevance of the subject matter to their lives and future professions. The instructor engages students in active learning to produce authentic and creative works. Key related terms: active learning, collaborative, modeling disciplinary process, metacognition, culturally knowledgeable (Ambrose et al., 2010).

Table 1: Dimensions and Foundations of Inclusive and Effective Teaching

|

Dimensions |

Definition |

|

Welcoming and Collaborative |

classroom environment is inclusive, incorporates peer and instructor interactions |

|

Empowering and Supportive |

instruction is responsive to student learning needs |

|

Structured and Intentional |

course design, learning materials, assessments, and lessons advance specific learning objectives |

|

Relevant and Engaging |

active learning opportunities are connected to student life experience |

|

Foundations |

Definition |

|

Evidence-Based |

informed by relevant teaching and learning research |

|

Student-Centered |

prioritizes student perspectives and outcomes |

|

Reflective |

considers goals, practice, outcomes and feedback |

|

Continuously developing |

informed by professional development and peer dialogue |

The Four Foundations of Inclusive and Effective Teaching

In addition to the four dimensions, TFELT identified four Foundations of Inclusive and Effective Teaching, also summarized on Table 1. These foundations may not be observable by students but are important in the scholarship and professional development of the educator and, therefore, provide a foundation for inclusive and effective teaching. TFELT, working with the MU community, identified the following foundations (TFELT, 2021):

- Evidence-Based – The educator uses current research on learning and teaching to design and update their courses (Lovett et al., 2023).

Example: An instructor changes how she forms student laboratory groups based on research that single–gender groups performed statistically lower on reasoning activities than mixed gender groups (Paine & Knight, 2020).

- Student-Centered – The educator engages students as partners in the learning process and considers student perspectives and experiences when deciding what is learned, how it is learned, and how learning is assessed (Felten & Lambert, 2020).

Example: An instructor designs game-based learning activities to broaden student engagement and participation (Bisz & Mondelli, 2023).

- Reflective – The educator sets goals and changes the course based on information gathered in their course, both the assessments of student learning and, separately, the ongoing feedback from students, peers, and self-evaluation (Namaziandost et al., 2023; Winstone & Boud, 2020).

Example: Students incorrectly answer assignment questions that ask them to apply new concepts with some of the difficult concepts from earlier exam units. The instructor talks to peers and creates a post-exam activity to help students understand difficult concepts before shifting to new material.

- Continuously Developing – The educator engages in professional development on an ongoing basis to adjust to changes that happen in the discipline, in our students, and in our society (Guerra et al., 2023).

Example: ChatGPT, an open-access Generative Artificial Intelligence, became mainstream in 2023. The instructor realized he needed to teach students how to appropriately use the new tool. To learn more on how he could guide the use of this technology, he participated in a series of campus workshops (Chiu, 2024).

Developing New Processes for Three Areas of Teaching Assessment

Upon completing the development of MU’s new definition and model, TFELT divided into three working groups. Each group investigated and developed proposals for innovating the evaluation on teaching in terms of the three primary sources of evidence typically used to document effective teaching: student feedback, peer review, and evidence-based instructor self-reflection. To develop recommendations aimed at fostering professional growth and development, the working groups considered two levels of teaching evaluation: formative and summative assessment. Formative assessment is a process of evaluation intended solely to provide feedback for reflection and improvement and thus is kept separate from teaching evaluation processes connected to personnel decisions such as tenure and promotion. Teaching evaluation intended for making such merit-based decisions involves a process of summative assessment: the evaluation of performance relative to established expectations (Tobin et al., 2015). While most instructors associate the “evaluation of teaching” with summative assessment procedures, TFELT decided to develop and promote parallel formative assessment recommendations for each of the three areas examined by the working groups.

Student Feedback

One working group was charged with exploring innovative changes in the use of end-of-semester student survey data to evaluate teaching. The status quo in this area was the use of scores from a single global “teaching effectiveness” item on the survey as the sole metric for assessing student responses to teaching. TFELT initially expected their primary recommendations in this area would focus on developing new processes for interpreting and reporting survey results in ways that would support a richer, multifaceted and growth-focused approach to evaluating student feedback data. This work resulted in TFELT’s recommendation to improve processes of student feedback data collection and reporting. The goal was to assist instructors in generating data reports that could compare results in an instructor’s different course types and demonstrate longitudinal trends in student responses. In addition, the task force recommended the elimination of normative data comparisons between instructors for summative teaching evaluation, as this practice is inaccurate and often problematic (Berk, 2013; Linse, 2017).

The working group quickly identified a need to develop a new student feedback survey instrument. After examining the current survey form through the lens of the new Dimensions of Inclusive and Effective Teaching, the working group determined that the survey items and resulting constructs did not provide complete evidence regarding some important areas of teaching practice. Additionally, the survey asked students to provide responses in areas outside of the reasonable scope of student ability (Kreitzer & Sweet-Cushman, 2022), including the instructor’s content area expertise and the appropriateness of teaching strategies. These findings led TFELT to recommend the formation of an interdisciplinary design team to develop and pilot a new survey instrument. The design team, created in March 2021, grounded their work on recommendations from research on student feedback surveys, relevant and appropriate psychometric norms for developing and testing assessment tools, and the availability of previously validated and nationally recognized survey items from diverse sources. Goals for the new instrument included focusing survey items on student perceptions of the course and the learning environment that are relevant to effective teaching practices, as well as replacing the single-item global teaching effectiveness score with scores on five survey constructs, each comprised of multiple survey items, aligning with the Dimensions of Inclusive and Effective Teaching. The initial instrument was drafted in the spring of 2021; four rounds of pilot testing and revision were conducted between May 2021 and December 2022. During this time the design team held community meetings across campus to collect feedback on the various survey revisions. The new survey was implemented university-wide at the end of the Fall 2023 semester.

Finally, TFELT recommended that the university promote the use of formative student feedback on teaching by instructors. The early collection of student feedback at the midpoint of the semester, and perhaps even earlier, enables the instructor to adjust the course and teaching strategies as needed. This practice also enables instructors to communicate the utility and importance of teaching feedback to students during the course. This practice has been associated in student feedback research to higher student response rates (Chapman & Joines, 2017) and improved quality of written feedback comments for end-of-semester surveys. Most recently, MU’s Assessment Resource Center worked with the T4LC to revise MoCAT (“Missouri Cares About Teaching”), the university-wide midterm student feedback survey tool, to align with the new summative student feedback instrument.

Peer Review

Another TFELT working group was charged with developing new tools and procedures for a university-wide peer review process. The status quo in this area across campus was inconsistent in design, implementation, and outcomes, varying widely between academic units. While some departments and colleges used rigorous procedures and intentionally developed instruments, others relied primarily on idiosyncratic letters written following a classroom observation by reviewers selected by the instructor being reviewed. Because of the variable frequency and quality of available peer review evidence, TFELT discovered that this evidence would often be discounted by review committees in favor of more “objective” student feedback data. Given these concerns, the working group pursued three interconnected lines of work to develop recommendations for improving the peer review of teaching.

First, after consulting a Deans’ Office workload survey from 2019 and consulting with colleagues in academic units across campus regarding their current approaches to peer review, the group drew on research findings as well as examples of peer review tools from University of Southern California, University of Oregon, and Vanderbilt University to develop new tools for formative and summative peer review of teaching. Following the recommendation of the American Educational Research Association (AERA) to use “formal observation protocols” for classroom observation (AERA, 2014, p. 3), an inventory of research-informed effective teaching practices was developed that aligns with the four Dimensions of Inclusive and Effective Teaching. The practices on this inventory included not only elements of teaching typically accessible to peer reviewers during classroom observations, but also elements of effective course design and learning materials that reviewers can examine in the instructor’s learning management system course site. This latter area of peer review was informed in part by a similar inventory used in the Quality Course Review process for online courses by Missouri Online. The items on the inventory, as was the case for the new student feedback survey, were also designed to apply to as many kinds of courses and teaching modalities as possible, which enables reviewers to consider peer review evidence based on a commonly shared set of best practices for Inclusive and Effective Teaching.

Two parallel tools using the same items and categories were developed. The first was for formative teaching assessment, using a simple checklist format. The second was for summative teaching assessment, using a rubric format to identify relative levels of effectiveness. Based on feedback from focus group sessions, TFELT did not include numerical scores on these instruments, given the potential negative incentives caused by a perceived “measurement” of objective teaching quality. Instead, the design philosophy of the tools focused on fostering teaching growth and development.

In addition to the new peer review tools, the working group drew on research and exemplary processes from other institutions to develop a three-stage protocol for a given peer review (Fletcher, 2018). These three stages apply to formative and summative peer reviews. First, the peer reviewer and the instructor have an initial meeting in which they discuss the nature of the course, the instructor’s broader teaching context, and particular teaching objectives and challenges about which the instructor desires specific feedback. Second, the peer reviewer observes the instructor’s teaching in the selected class, either through in-person observation in the in-person learning environment and/or through observation of instructor/student interactions and assignment feedback in online courses. This stage also involves the examination of the instructor’s course materials. Finally, the peer reviewer and instructor under review have a post-observation meeting in which the reviewer can share observations and suggestions, and the instructor can ask and answer additional questions. This final meeting not only provides the instructor with helpful feedback but also gives the reviewer an opportunity to ask about aspects of teaching that may not have been visible during the observation. For example, certain aspects of in-class instruction or activities may take place during different parts of the course or may not be as readily observed by a reviewer, such as aligning learning activities with assessments and learning objectives, providing students with assignment feedback, or interacting with students outside of class. Discussing such teaching elements enables the review to be more complete than one based solely on a single classroom observation.

Finally, given the significant changes introduced by this new approach to peer review, the working group developed training materials and workshops to provide instructors with opportunities to learn and practice these innovations (see Fletcher, 2018). The reviewer training resources developed during this work include online mini-courses with instructional videos and textual content. Additionally, in-person workshops enable participants to put the new tools into practice with video examples of classroom teaching. The working group also developed recommendations for the frequency and sequencing of formative and summative peer reviews for instructors, as well as guidelines for departments to identify and assign peer reviewers, and a recommendation to develop an online system to manage and archive peer reviews. A pilot program for formative peer review was conducted in the Spring 2020 semester to assess the development of training and the efficacy of the new observation checklist. Pilot testing, the collection of feedback on the tools and processes during community engagement sessions across campus, and refinement of the tools continued through the Spring 2021 semester. A workflow guide document was also developed to assist in implementing the peer review process. Currently, academic units may elect to adopt the new peer review processes, and implementation across campus is broadening.

Self-Reflection

TFELT, recognizing the value of regular self-reflection as an important practice for Inclusive and Effective Teaching (see Blumberg, 2015; Kirpalani, 2017), recommended the implementation of an annual teaching self-reflection as a means for including instructor-generated evidence into the university’s annual review process. Self-reflection provides, first and foremost, an effective mechanism for formative teaching assessment aimed at improving professional practice based on sense-making of prior experiences (Blumberg, 2015). The tool developed by the self-reflection working group sought to include distinct elements of teaching for learning into an integrative reflection experience. These include:

- the instructor’s teaching philosophy

- contextualization of the instructor’s student feedback

- inclusive teaching practices

- the alignment of course learning objectives, assessments and learning activities

- the four Dimensions of Inclusive and Effective Teaching

- self-assessment of previous teaching goals and the establishment of new goals.

The working group proceeded to develop an initial draft of a self-reflection tool based on four guiding priorities: that the self-reflection process be efficient, substantive, balanced, and useful for professional development. At the same time, TFELT concluded that the incorporation of self-reflection documents into the summative teaching assessment process, particularly for promotion and tenure, could be problematic. One primary concern was the perceived conflict between the value of authentic reflection on teaching challenges and difficulties on the one hand and the potential that such a document might be used by peer reviewers as evidence of problematic teaching. This concern has the potential to incentivize instructors to conduct inauthentic self-reflection, focusing solely on teaching strengths to minimize their vulnerability. TFELT ultimately recommended that, while self-reflections should be required for the annual review process, the contents of that self-reflection would only be accessible to department chairs in a position to provide the instructor with direct formative feedback. These chairs can then confirm completion of annual self-reflections, without disclosing the contents, to review committees for promotion and tenure purposes. This provides evidence that the instructor is regularly conducting research-supported best practice for intentional, learner-centered teaching.

The working group conducted three pilots of the teaching self-reflection between November 2020 and March 2021. Following each pilot, the tool was revised to make it both easier and more flexible to complete by eliminating prompts, consolidating others, and providing instructors with choices for responding to some important areas. The working group also developed a Teaching Improvement Plan as an optional opportunity for more in-depth formative self-reflections. The T4LC also developed online and in-person training opportunities for peer reviewers and instructors.

The self-reflection was first made available on an opt-in basis for academic units and individual instructors on campus beginning with the Spring 2022 annual review process. The roll-out experienced some challenges due to unclear communication within some colleges as well as technical difficulties introduced by the Qualtrics online survey application used to administer the annual review. The university’s Academic Affairs Committee and the T4LC responded with revisions to the process and training sessions. The teaching self-reflection became a required element for annual reviews beginning with the Spring 2024 annual review process. As one outcome of the bumpy initial implementation of the required self-reflection using the Qualtrics survey tool, the T4LC worked with the Academic Affairs Committee in Spring 2023 and again in Spring 20244 to analyze feedback on the self-reflection. What resulted were several improvements on the process: a reduction and streamlining of reflection prompts that also minimized redundancy with other components of the annual review, as well as moving the tool out of Qualtrics and directly into the online annual review self-report for easier and more user-friendly completion. In addition, the Provost’s Office and the T4LC have worked together to ensure that online support information for self-reflection is consistently aligned and updated as process improvements are implemented.

Incentives

One of the key charges of TFELT was to create suggestions about how effective teaching could be rewarded and incentivized. A separate working group within TFELT was created to address this need. Incentives can be helpful, in part, because change can be difficult. The changes described within this chapter were substantive and evidence based. Implementing the new tools and responding to the new dimensions and foundations of effective teaching requires an investment of time that should be acknowledged. Hopefully, instructors will see the impact of their efforts on students’ academic success and learning, and in their own effectiveness in the classroom. It can also be helpful to offer extrinsic incentives, such as monetary incentives, awards, and professional development opportunities and resources. In this section, we describe the merit-based and non-monetary awards that TFELT recommended to recognize effective teaching.

For monetary awards, TFELT recommended a merit-based system where the three evaluation tools (student feedback survey, peer review, and self-reflection), and the holistic tool that draws evidence from these three individual tools, could be used to create a star rating ranging from one to five stars. Leaders at the college or departmental level would be tasked with ensuring a three-star average across the academic unit. A separate pool of funds, provided by the Provost or Deans would be used to reward instructors according to a formula that considered the star ratings, the percentage of time allocated to teaching, and the amount of funding per star available that year. TFELT suggested that instructors receiving 1 or 2 stars would have a smaller incentive and could apply that toward professional development for teaching. Those with three to five stars could receive the funds as a direct payout. We illustrated this system with an example of one department of eight instructors where $20,000 was set aside for incentive funding. In this example, 24 stars were allotted (to average three stars across the department), and each star was worth $1,666.67 in incentive funding. Someone whose teaching represented 40% of their role would receive $666.67 for one star and $3,333.33 for five stars in this scenario. An instructor whose teaching comprised 80% of their role would have a larger multiplier so their incentive in this example would range from $1,333.33 for one star to $6,666.68 for five stars.

TFELT suggested this system because it offered a way to be responsive to fluctuating resources within a given year while offering a transparent way to incentivize and reward inclusive and effective teaching efforts across all instructors. The many community feedback sessions further emphasized the need to acknowledge the teaching efforts of tenured, tenure-track, and non-tenure track faculty, who may have different teaching loads. Drawing from multiple forms of evidence strengthens the quality of the assessment and hopefully results in targeted strategies for improvement, as needed. TFELT also suggested non-monetary awards that recognize effective teaching across the four key dimensions described in an earlier section. Educators could be nominated for exemplifying one of the dimensions and a committee could be tasked with reviewing the nominees and selecting an awardee for each category. These could be awarded at both the college and university levels. Recipients of all four awards might receive an additional award for Excellence in Evidence-Based Teaching. While there are no current plans to distribute merit awards by college or department, there are plans to create a campus-wide teaching award for inclusive and effective teaching, learning, and assessment.

Change Management

In 2020, the backdrop to the TFELT work devolved from a business-as-usual vibe into a global pandemic, and University leaders were hesitant to mandate new forms of teaching evaluation at that time. Instead, the institution focused on developing high-quality training for each of the newly created tools for documenting effective teaching. Open access, multi-modal online modules for instructors were complemented by synchronous in-person, scenario-based workshops. As more educators on campus became competent and confident with the new framework and tools, pilot projects helped to socialize so much newness to a recovering community. Departments within the colleges of Engineering, Education and Human Development, and Arts & Sciences were early adopters and shared their experiences at the steady stream of teaching events, conferences, and other venues. Chairs and Faculty Council committee members shared their perspectives on what was working well and what needed immediate attention due to redundancy, workload concerns, and faulty technology platforms. Slowly and intentionally, the Office of the Provost began incorporating new requirements to be provided as part of the annual review and promotion and tenure processes. They launched the newly required, end-of-semester student feedback instrument and the aligned and optional new mid-semester student feedback form. This “gradual release” change management process has given autonomy to individual academic units about their rate of adoption and is leading our university to achieve its overall goal.

Conclusion

In this chapter we described the process of revamping MU’s evaluation of teaching from over-emphasis on a dated student evaluation form to a new approach that accounts for student feedback, peer review, and self-assessment of teaching. The process for making these changes was intensive. It required two years of dedicated involvement by TFELT and subsequent years of continued integration and advocacy by T4LC staff. The proposed changes to assess teaching align with a newly created model of inclusive and effective teaching that is evidence-based, allows for formative and summative reviews, and reflects the input of MU stakeholders who helped shape these discussions.

There is much to celebrate about TFELT’s accomplishments under the challenging circumstances of working through a global pandemic. This contributed to an extended timeline for the committee’s work (two years instead of one) and led to delays in implementing recommended changes. In hindsight, further assurances and clarity related to how and when TFELT’s recommendations would be implemented may have facilitated the committee’s work and led to more buy-in from university stakeholders along the way and momentum in getting all parts of the plan implemented. For example, the community sessions were key to incorporating helpful changes in response to diverse needs across campus. Some instructors who were skeptical about whether any changes would result did not participate in TFELT’s activities but wanted their perspectives included once changes were implemented. Fortunately, future assessment and updating will provide more opportunities for everyone to contribute ideas and strategies on how MU evaluates inclusive and effective teaching.

References

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., & Norman, M. K. (2010). How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching. Jossey-Bass.

American Educational Research Association. (2014). Rethinking faculty evaluation: AERA report and recommendations on evaluating education research, scholarship, and teaching in postsecondary education. AERA.

Berk, R.A. (2013). Top 10 flashpoints in student ratings and the evaluation of teaching. Stylus Publishing.

Bisz, J., & Mondelli, V. L. (2023). The educator’s guide to designing games and creative active-learning exercises: The allure of play. Teachers College Press.

Cavanagh, S. (2016). The spark of learning: Energizing the college classroom with the science of emotion. West Virginia University Press.

Chapman, D.D., & Joines, J.A. (2017). Strategies for increasing response rates for online end-of-course evaluations. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 29(1), 47-60.

Chiu, T.K.F. (2024). Future research recommendations for transforming higher education with generative AI. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 6, 100197 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2023.100197

Deslauriers, L., McCarty, L. S., Miller, K., Callaghan, K., & Kestin, G. (2019). Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(39), 19251–19257.

Felten, P., & Lambert, L. M. (2020). Relationship-rich education: How human connections drive success in college. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Fletcher, J.A. (2018). Peer observation of teaching: A practical tool in higher education. Journal of Faculty Development, 32(1), 51-64.

Guerra, A., Nørgaard, B., & Du, X. (2023). University educators’ professional learning in a PBL pedagogical development programme. Journal of Problem Based Learning in Higher Education, 11(1), 36-59. https://doi.org/10.54337/ojs.jpblhe.v11i1.7375

Kirpalani, N. (2017). Developing self-reflective practices to improve teaching effectiveness. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 17(8), 73-80. https://articlegateway.com/index.php/JHETP/article/view/1436

Kreitzer, R.J., & Sweet-Cushman, J. (2022). Evaluating student evaluations of teaching: A review of measurement and equity bias in SETs and recommendations for ethical reform. Journal of Academic Ethics, 20, 73-84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-021-09400-w

Lovett, M.C., Bridges, M.W., DiPietro, M., Ambrose, S.A., & Norman, M.K. (2023). How learning works: Eight research-based principles for smart teaching (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

MU Teaching for Learning Center. (2024). Review of teaching. https://tlc.missouri.edu/review-of-teaching/

Namaziandost, E., Heydarnejad, T., & Azizi, Z. (2023). The impacts of reflective teaching and emotion regulation on work engagement: Into prospect of effective teaching in higher education. Teaching English Language Journal, 17(1), 139-170. https://doi.org/10.22132/TEL.2022.164264

Ngatia, L.W. (2022). Student-centered learning: Constructive alignment of student learning outcomes with activity and assessment. In R.J. Blankenship, C.Y. Wiltsher, and B.A. Moton (Eds.), Experiences and research on enhanced professional development through faculty learning communities (pp. 72-92). IGI Global.

TFELT. (2021). Task Force to Enhance Learning & Teaching (TFELT) Proposal. University of Missouri Teaching for Learning Center. https://tlc.missouri.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2023/10/TFELT-Report-Collected-Documents-Progress-Update-March-2021.pdf

Tobin, T.J., Mandernach, B.J., & Taylor, A.H. (2015). Evaluating online teaching: Implementing best practices. Jossey-Bass.

Winstone, N. E., & Boud, D. (2020). The need to disentangle assessment and feedback in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 47(3), 656–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1779687