Joints and Movement

Objective 9.10

9.10.1 Explain the functional classification of joints.

9.10.2 Characterize synarthrotic, amphiarthrotic, and diarthrotic joints.

9.10.3 Explain the anatomical classification of joints.

9.10.4 Characterize fibrous, cartilaginous, and synovial joints.

9.10.5 Compare and contrast functional and anatomical classification of joints.

9.10.6 Describe the key features of a synovial joint.

9.10.7 Describe the different movements of a joint.

Now that we’ve got the bones figured out, we’ll finish this unit by turning to the connections between bones — joints. The root arthro- means joint. From this, for example, we get arthritis (inflammation of a joint) and arthroscopy (visualizing inside a joint with a small camera).

Joint Classifications

There are two systems for classifying joints. The first is the functional classification; the second one is an anatomical classification. These two systems are not mutually exclusive; rather, they are related and there is a lot of overlap in the two classification schemes.

The functional classification of joints has three divisions based on the joint’s function (ie, degree of movement).

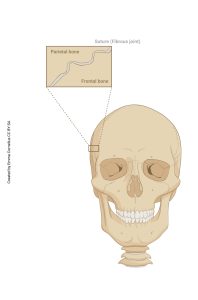

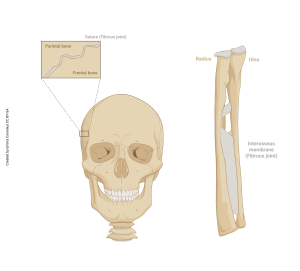

1. Synarthrotic joints (syn-, without) are not capable of any functional movement. Of course, there is a chance that the joints in your skull can move, but you probably would prefer they didn’t.

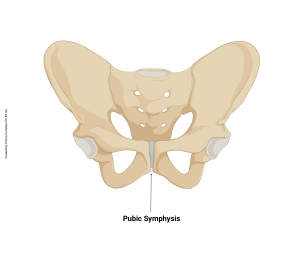

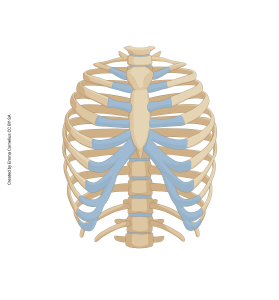

2. Amphiarthrotic joints are slightly moveable. The joints between the vertebrae and the ribs, as well as the joints between the ribs and the sternum, are capable of a small amount of movement, which we utilize when we do chest compressions in CPR. Similarly, during childbirth, the pubic symphysis is slightly moveable.

-

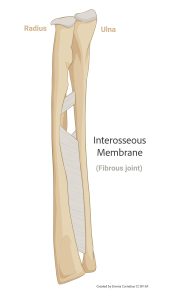

- Another example of amphiarthrotic joints are the sheets of connective tissue between the radius and ulna and another between the tibia and fibula called the interosseus membranes. The name, of course, means “between the bones”

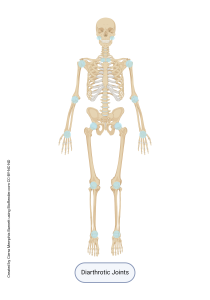

3. Diarthrotic joints are fully moveable. The shoulder, elbow, hip, and knee joints are examples of these. There are many others.

The anatomical or structural classification of joints also has three divisions, but is based on how the bones at the joint are held together.

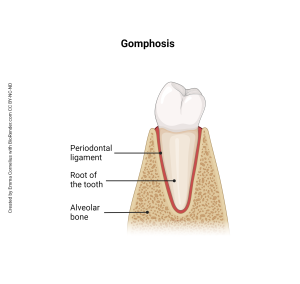

1. Fibrous joints are made of a band of dense irregular connective tissue. This type of joint holds together the bones of the skull; it is also what holds teeth in place. (Technically, since teeth are not bones, the connection between each tooth and its bony socket is called a gomphosis. However, because teeth and bones are very similar, most people would classify this a fibrous joint.)

-

- The interosseous membranes, seen as amphiarthrotic joint tissue, are also fibrous joints in the anatomical classification.

2. Cartilaginous joints like that between true ribs and sternum or between false ribs and true ribs, is where bones are held together by cartilage.

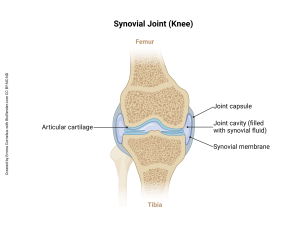

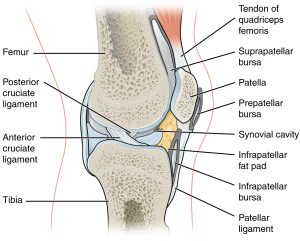

3. Synovial joints have a synovial cavity present which is filled with synovial fluid. Articular cartilage covers the bones where they are in contact. The entire structure is contained by a joint capsule.

There is a rough, but imperfect, alignment between the functional and structural/ anatomical classification schemes for joints. Some joints are easy to classify using both schemes. For example, the joints between the bones of the skull are clearly synarthroses functionally, and fibrous joints anatomically. They are immovable joints bound together by a band of dense connective tissue.

Using the same approach, the hip joint is a diarthrosis and also a synovial joint. Likewise, the temporomandibular joint is also a diarthrosis (functionally) and a synovial joint (anatomically).

(anatomically).

As already mentioned, some joints or joint-like structures resist simple classification. For example, the joint between a tooth and the mandible (or maxilla), a gomphosis, is functionally a little bit synarthrosis and a little bit amphiarthrosis. Anatomically, it is clearly a fibrous joint. The small amount of movement in the gomphoses between teeth and bone is what keeps orthodontists busy straightening teeth.

Synovial Joints are typically diarthroses in the functional classification. Ideally, the structures of a synovial joint are specialized to allow freedom of movement without friction or strain. Since this is a joint, there are two or more bones involved that must be held together.

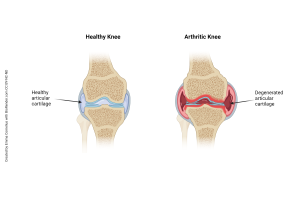

At the place where bones might rub against each other there is a pad of articular cartilage (hyaline) that both reduces friction and provides a cushion at the joint. Since bone has a large mineral component, two moving bones in direct contact would cause damage to both (and does, in the disease arthritis). The articular cartilage prevents this from happening, and provides a slightly elastic but strong tissue at the place where joint motion occurs.

A set of membranes called the joint capsule holds the bones in the correct position and also encloses the fluid portion of the joint. The joint capsule is made up of a strong outer fibrous capsule, and an inner synovial membrane that secretes synovial fluid. This fluid helps to lubricate and cushion the joint.

At points where tendons and ligaments move across bone, there are slippery bags called bursae (singular bursa, Latin for purse) that allow these to move past each other without friction.

One “feature” of synovial joints is that since they must allow for free movement; they are often structurally imperfect and subject to damage.

Clinical Connection

Common Joint Disorders

Aging joints have three common problems. Osteoarthritis is an inflammation of a joint, particularly a synovial joint. (Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune process which affects joints, and is a completely separate disease.) Some degree of osteoarthritis is inevitable with aging. As the “parts” of the joint become worn, there is direct contact between bones and the bone produces little spikes (osteophytes) in response as it remodels. The osteophytes cause further damage to the joint, and the process spirals downward.

Bursitis is an inflammation of the bursa which allows tendons and ligaments to slide past bones at joints.

Although septic bursitis is sometimes seen, and is caused by microorganisms traveling to the bursal sac, a sterile bursitis is much more common. The bursa becomes inflamed and swollen.

Sprains are microscopic tears in a ligament. Obvious tears, where the collagen fibers completely separate from each other, are also called sprains. Orthopedic surgeons use a grading system (from 1 to 3) to describe the degree of tearing, with 1 describing the microscopic tears and 3 describing the total ripping apart of a ligament.

In contrast, strains are tears in a muscle or the tendon that connects muscle to bone.

Joint Movements

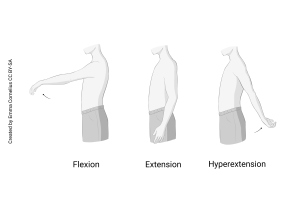

Most movements at joints are angular movements. These movements change the angle of a joint. For example, if you lift an imaginary dumbbell, as you contract the biceps brachii muscle in your arm, you are decreasing the angle at the elbow joint. If you let your arm drop back into anatomical position, you are increasing the angle at the elbow joint.

Movements that decrease the angle of a joint are called flexion. Movements that increase the angle of a joint are called extension. If an extension movement (increasing the angle of a joint) reaches the anatomical position and keeps going, it is called hyperextension.

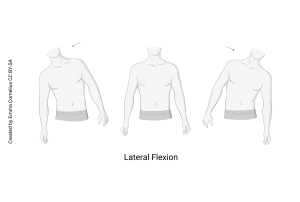

Since the vertebral column can bend sideways, the movement of lateral flexion is only possible in the spine.

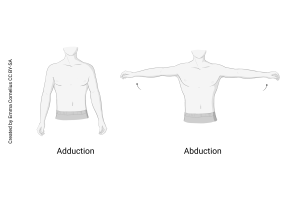

If someone comes to your house and abducts your dog, they are taking your dog away. A motion that takes a body part away from the midline is abduction. A motion that brings a body part closer to the midline is adduction. Anatomists usually say “ay-bee-duct” or “ay-dee-duct” to indicate which they mean, to avoid confusion when listening.

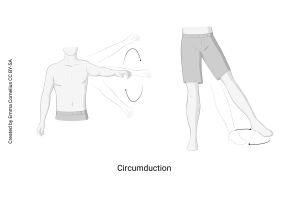

A circular movement with the shoulder or hip joint is circumduction. Note that these are neither flexion nor extension (they don’t change the angle of a joint) and neither abduction nor adduction (they don’t change the relationship of the body part to the midline).

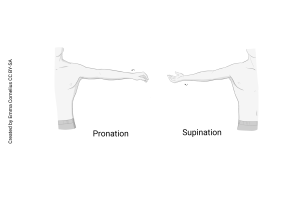

Supination and pronation are motions that occur at a few joints. Supination is, when starting with your palm facing backwards or downward, turning/rotating your palm to face forward or upwards. Often this is remembered by having to turn your palm upward to hold something in your hand, such as a cup of soup (holding soup=supination). Pronation is the opposite movement. In pronation you rotate the hand so the palm faces backwards or downwards. When you are typing or using a computer mouse, your hand is typically in pronation.

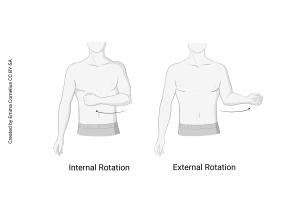

Some joints can also perform internal (medial) rotation and external (lateral) rotation. Internal rotation is a rotation towards the center of the body. External rotation is rotation away from the center of the body. These movements can be seen when looking at the movements at the shoulder joint.

Media Attributions

- U09-080 fibrous joints skull only © Cornelius, Emma is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U09-076 Pubic symphysis © Cornelius, Emma is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U09-080 fibrous joints inteross only © Cornelius, Emma is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U09-079 Diarthrotic Joints © Barnett, Cierra Memphis is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- U09-080 fibrous joints © Cornelius, Emma is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U09-081 ribs © Cornelius, Emma is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U9-082 and 084 synovial joint of the knee © Cornelius, Emma is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- U09-083 gomphosis © Cornelius, Emma is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- U9-082abursa synovial joint © Betts, J. Gordon; Young, Kelly A.; Wise, James A.; Johnson, Eddie; Poe, Brandon; Kruse, Dean H. Korol, Oksana; Johnson, Jody E.; Womble, Mark & DeSaix, Peter is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- U09-085 Healthy vs Arthritis © Cornelius, Emma is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- U09-086 flexion, extension © Cornelius, Emma is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U09-087 lateral flexion © Cornelius, Emma is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U09-088 adduction, abduction © Cornelius, Emma is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U09-089 circumduction © Cornelius, Emma is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U09-090 pronation, supination © Cornelius, Emma is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U09-091 © Cornelius, Emma is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license