Naming Anatomical Planes and Directional Terminology

Objective 1.3

1.3.1 Describe the human anatomical position and identify the major regions of the human body.

1.3.2 Define and identify the directional terms used in human anatomy.

1.3.3 Identify and describe the three cardinal planes used to section the body.

1.3.4 Locate the major body cavities and demonstrate an understanding of the three-dimensional relationship between the body cavities.

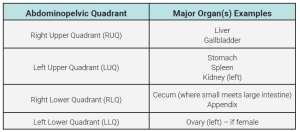

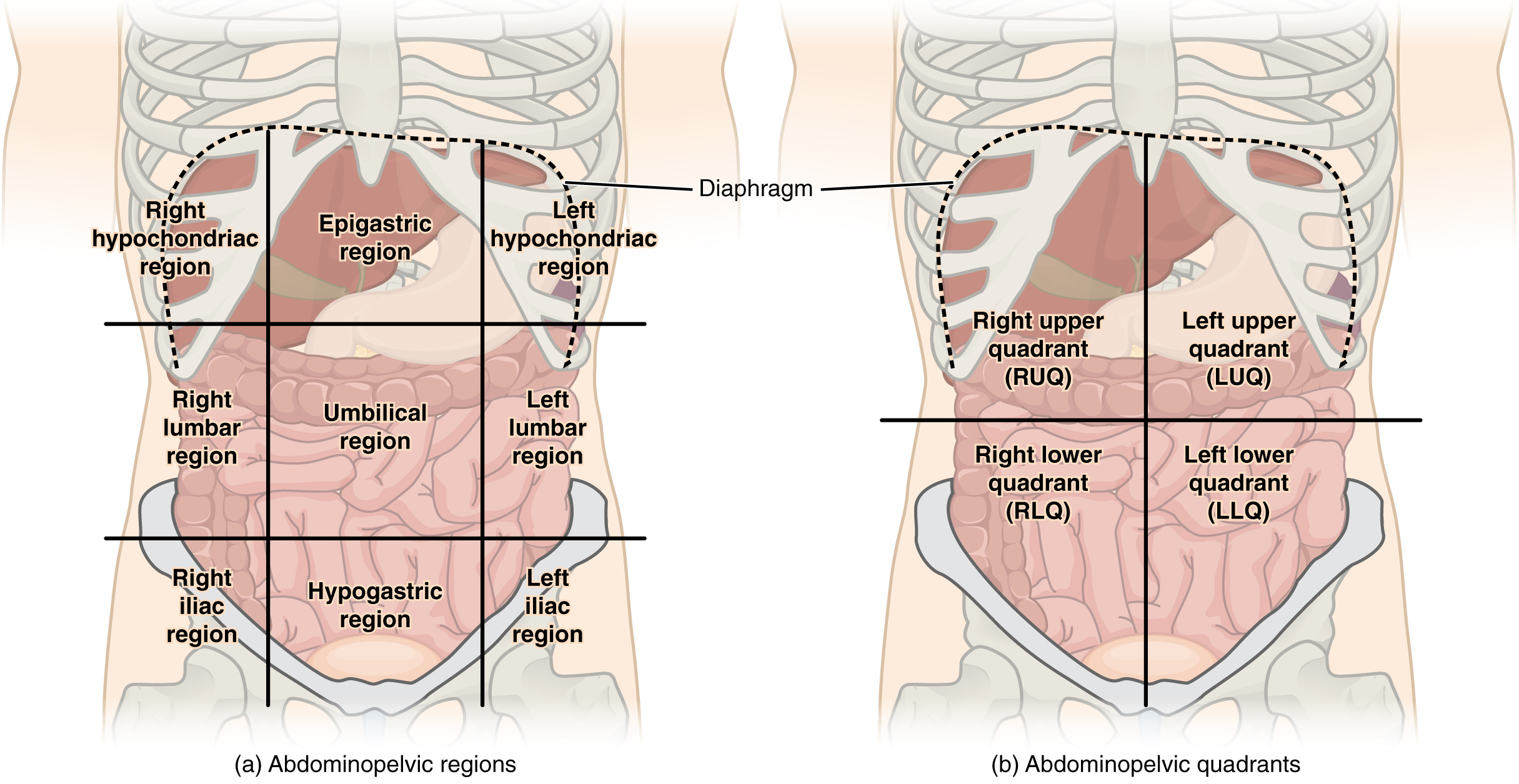

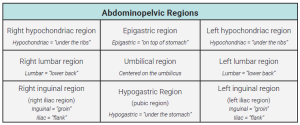

1.3.5 Identify the four abdominopelvic quadrants and the nine abdominopelvic regions, and the major organs that occupy them.

We will cover multiple topics in this objective:

- Anatomical position

- Directional terms

- Planes of section

- Body cavities

- Abdominopelvic quadrants and regions

- Regional anatomy

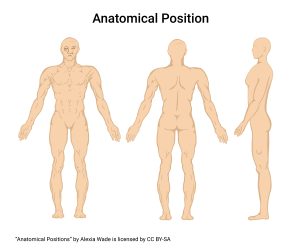

Anatomical Position

We need to define a single position for the human body so we can describe the relationship between various structures. For example, we use the term superior to mean “above” or “on top of”. You can put your hand on top of your head, but no one would say the hand is superior to the head. It’s the other way around.

We then define a “normal” position so that we can say where one structure is in relationship to another. We call it the human anatomical position.

In the anatomical position the subjects stands erect, facing the observer with the head level, the eyes facing forward, feet flat on the floor, feet directed forward, and the arms at their sides with the palms facing forward.

Now that we’ve defined a standard position, we’ll add words to describe specific locations on the outside surface of the human body. These are the terms commonly used in surface anatomy. We will also see all of these names again as we learn specific organ systems.

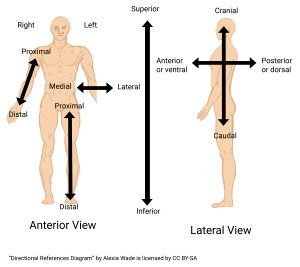

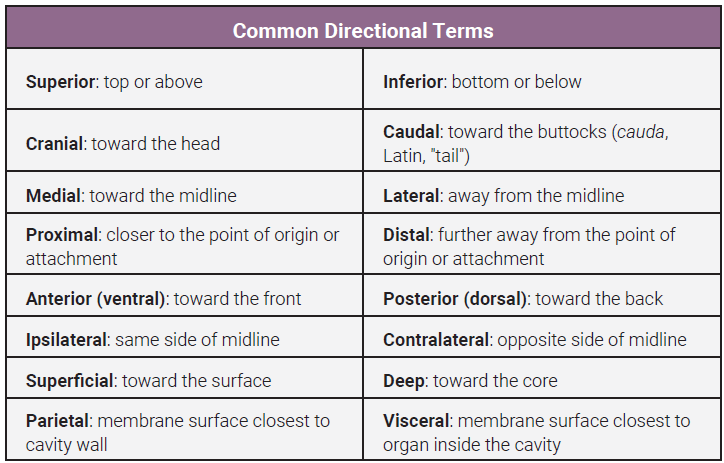

Directional Terms

Directional terms are pairs of words defining the two ends of an imaginary, two-headed arrow, like north and south; east and west. Before we use them, we have to imagine the human body in anatomical position.

Directional terms can relate to the structures on the body surface and to structures inside the body. Superficial means toward the surface. Deep means towards the core. Most organs inside cavities are covered with a double-layered membrane. Parietal is the membrane surface closest to the cavity wall. Visceral is the membrane surface closest to the organ inside the cavity. See the table for definitions of all of the directional terms we will study.

Let’s go through a few examples:

- The heart is superior to the bladder. The bladder is inferior to the heart.

- The nose is medial to the eye orbits. The ears are lateral to the nose.

- The sternum is anterior to the heart. The spinal column is posterior to the trachea.

- The right arm is contralateral to the left arm. The right arm is ipsilateral to the right leg. The right arm is contralateral to the left leg.

- The skin is superficial to the muscles. The muscle is deep to the skin.

- The visceral and parietal pleural membranes are examples of these terms. We will study them in depth in unit 17. The visceral pleura is the membrane that lines the surface of the lungs while the parietal pleura lines the wall of the thoracic cavity.

For all the structures named in this unit, you should be familiar with their relationship with each other. Example: “The brain is superior to the kidneys.”

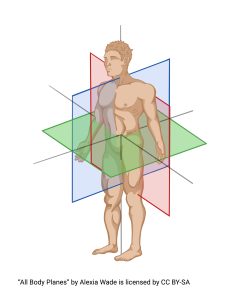

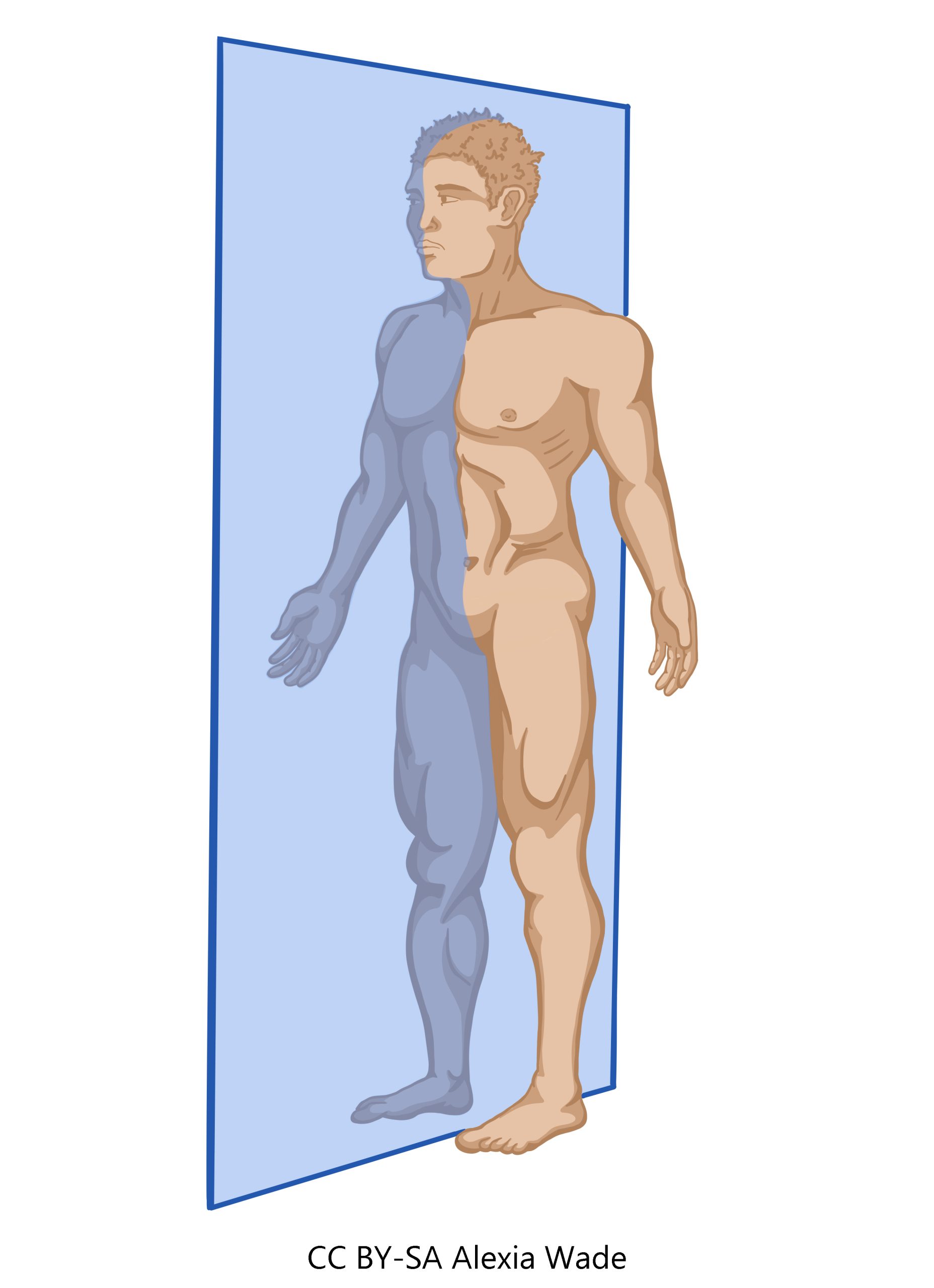

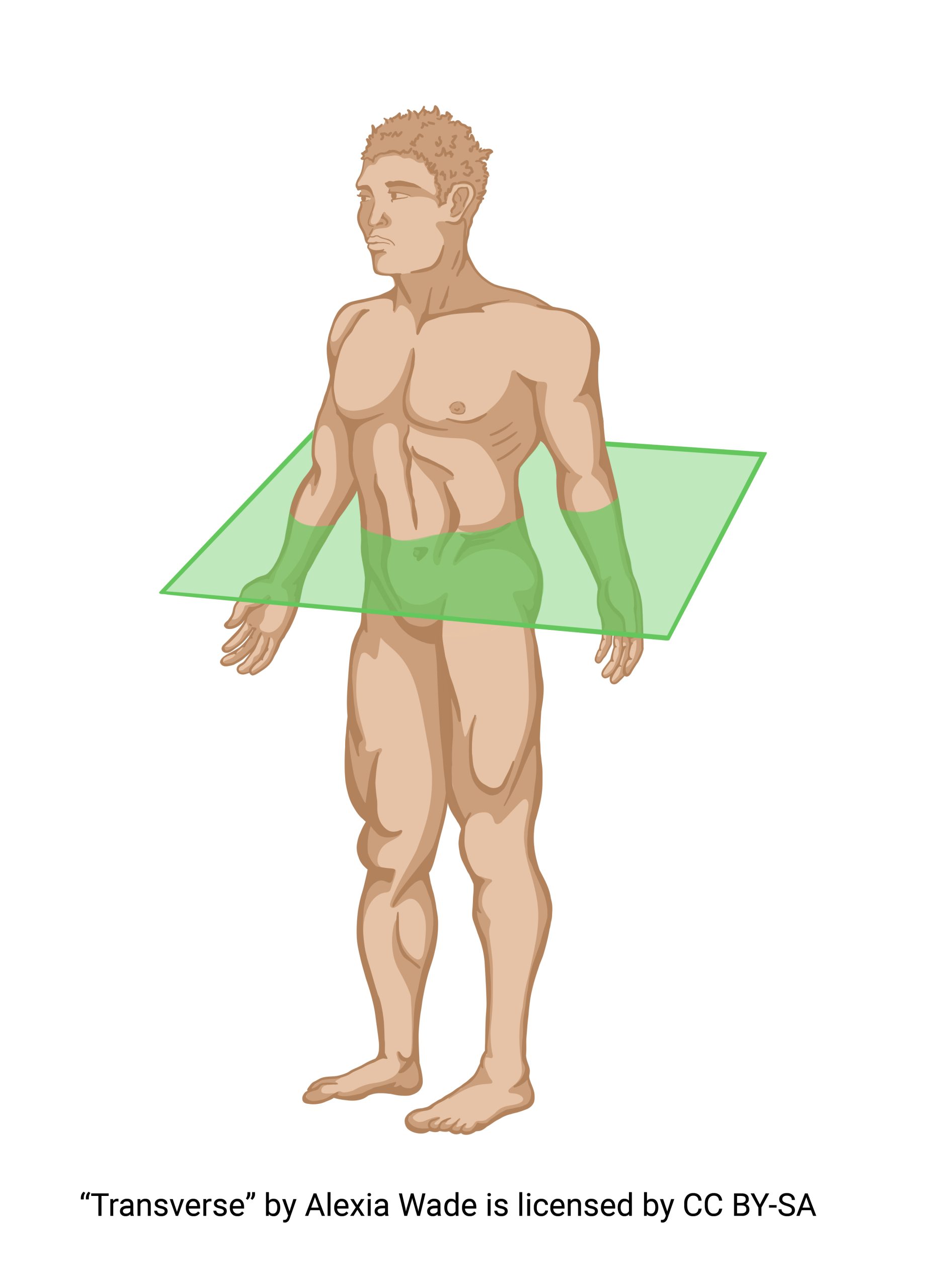

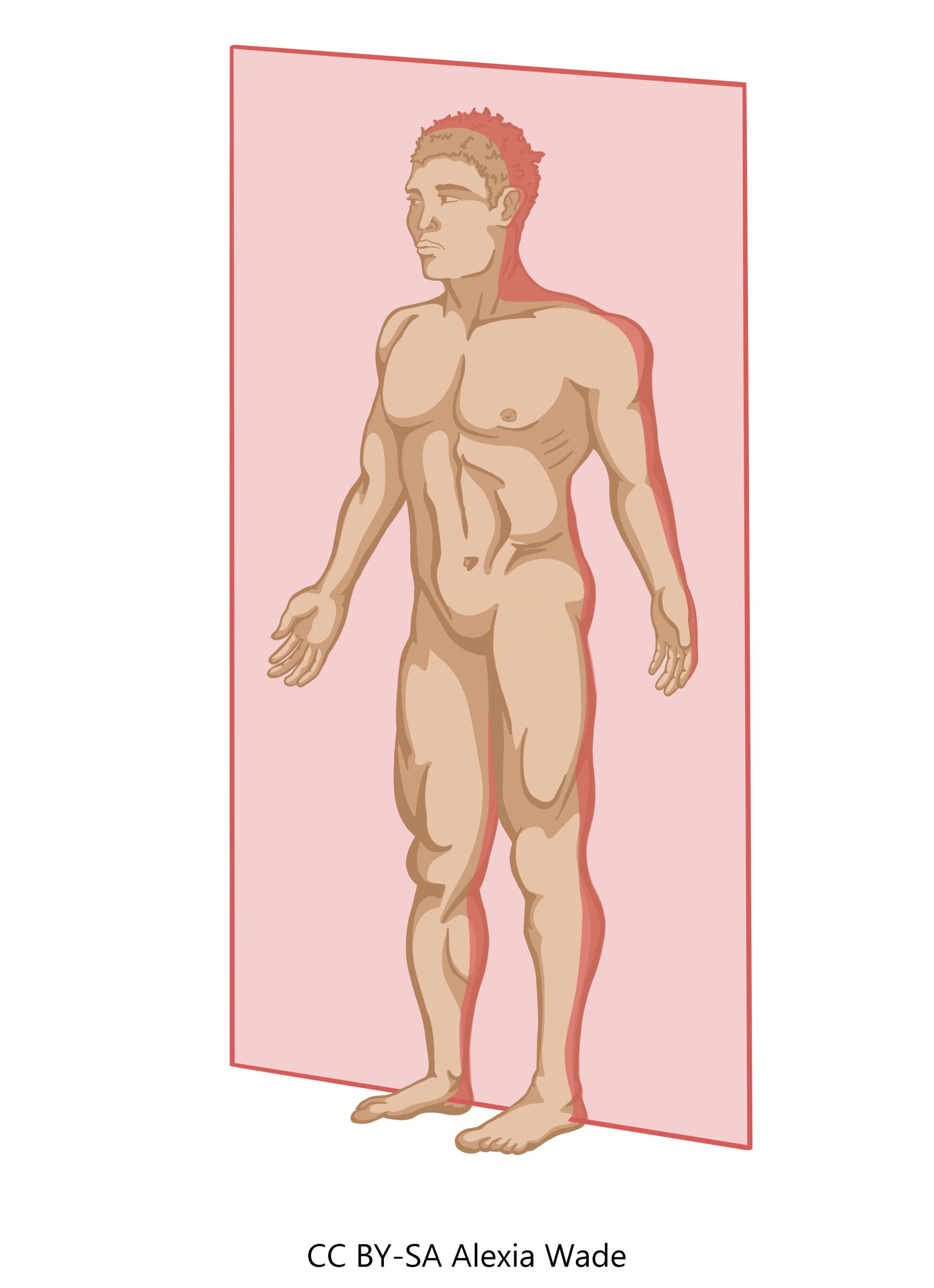

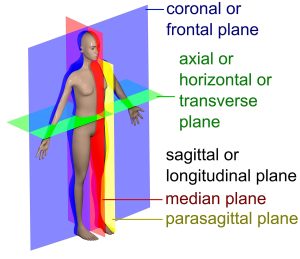

Body Planes

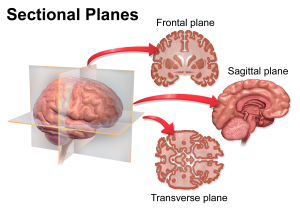

Next we will explore cardinal planes. There are three cardinal planes used to define sections through the human body.

1) sagittal: divides right from left sides of body.

2) transverse (also called horizontal): divides superior from inferior.

3) frontal (also called coronal): divides anterior from posterior (dorsal from ventral).

Note the importance of anatomical position in these descriptions. The transverse (horizontal) plane is parallel to the ground, which is how it gets its name. Yet, if you’re lying down on your back, the frontal plane is parallel to the ground. We still call it the frontal plane.

Technically, the sagittal plane is any section that divides left from right, but most anatomists use two more related terms: midsagittal (dividing the body into two equal, mirror-image halves) and parasagittal (all other sagittal planes). Sagittal and parasagittal are the same thing.

An oblique plane is any plane or section that does not fit the above descriptions. Because of the variations in cuts and the number of analyses, the number of possible sections in each of these planes is infinite.

In a sagittal cut, we can identify anterior and posterior, superior and inferior, but not right and left. We have divided the right from the left so we lose that information.

In a frontal cut, we can identify superior and inferior, left and right, but not anterior and posterior. We have divided the anterior from the posterior, so we lose that information.

In a transverse cut, we can identify anterior and posterior, left and right, but not superior and inferior. We have divided the superior from the inferior, so we lose that information. In each case, structures that are not seen in a surface view become visible.

You can also view organs in sections based on the cardinal planes. Notice how the shape of the section changes.

That’s the power of sectioning, as is done in many radiological studies such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) scans. In fact, “computed tomography” means using the computer to make slices from a series of low-dosage conventional X-rays.

Body Cavities

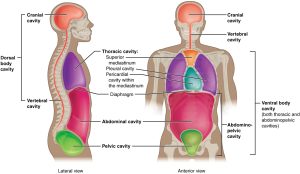

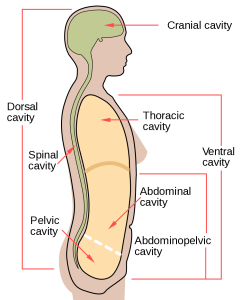

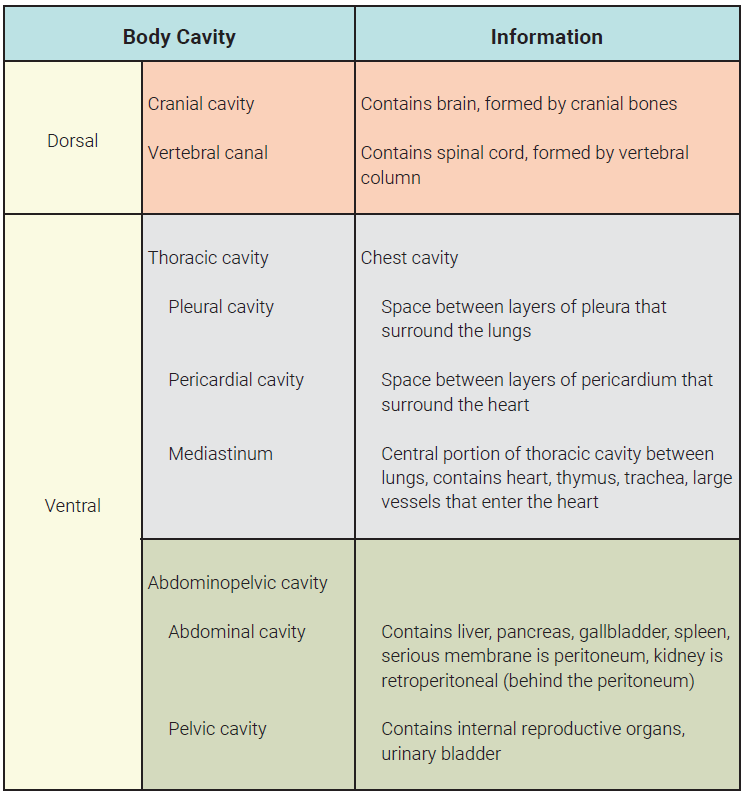

There are two main body cavities

- Dorsal (cranial and vertebral);

- Ventral (thoracic and abdominopelvic).

Each of these is subdivided into smaller cavities. The cranial cavity is in the skull; a hole in the bottom of the skull leads into the vertebral canal which is defined by the bony vertebrae.

The thoracic cavity contains the pleural cavities, pericardial cavity, and the mediastinum. The mediastinum contains the pericardial cavity, which in turn contains the heart. The pleural cavities contain the lungs.

The thoracic cavity is divided from the abdominopelvic cavity by the diaphragm. An imaginary line separates the abdominal and pelvic cavities within the abdominopelvic cavity.

The thoracic and abdominopelvic cavities are together called the ventral cavity. They are the adult derivatives of an embryonic cavity called the coelom (pronounced “seal-um”).

You should spend a lot of time thinking about these cavities, how they relate to each other, and how they relate to the body as a whole. For example, the thoracic cavity (chest) has a medial mediastinal cavity and two lateral pleural cavities. The heart is within the pericardial cavity and the pericardial cavity is within the mediastinum. The lungs are within the pleural cavities.

The pericardial cavity is therefore medial to the pleural cavities, and the pleural cavities are lateral to the pericardial cavity.

Abdominopelvic Quadrants & Regions

The abdominopelvic cavity is divided into either four quadrants or nine regions using surface features. To divide the surface of the abdomen into four quadrants, vertical and horizontal lines are drawn through the umbilicus (“belly button”) when the human body is in the anatomical position.

To divide the surface of the abdomen into nine regions, a “tic-tac-toe” pattern is centered on the umbilicus. The vertical lines are drawn through the middle of the clavicles (collarbones) and the horizontal lines are drawn at 1/3 and 2/3 of the distance between the diaphragm and the pelvic bone.

Regional Anatomy

The last topic of this objective is regional anatomy. Here is a list of the major regions of the human body and a graphic to match their location. You should be able to identify these regions on a graphic or photograph. (Note: Both the English term and the Greek or Latin term are given for each region; be familiar with both.)

- Head (cephalic)

- Skull (cranial)

- Base of skull (occipital)

- Face (facial)

- Forehead (frontal)

- Temple (temporal)

- Eye (orbital, ocular)

- Ear (otic)

- Cheek (buccal)

- Nose (nasal)

- Mouth (oral)

- Chin (mental)

- Neck (cervical)

- Spinal column (vertebral)

- Trunk

- Chest (thoracic)

- Breastbone (sternal)

- Breast (mammary)

- Shoulder blade (scapular)

- Back (dorsal)

- Abdomen (abdominal)

- Navel (umbilical)

- Hip (coxal)

- Loin (lumbar)

- Between hips (sacral)

- Pelvis (pelvic)

- Groin (inguinal)

- Pubis (pubic)

- Buttock (gluteal)

- Perineal

- Upper Extremity

- Armpit (axillary)

- Arm (brachial)

- Front of elbow (antecubital)

- Back of elbow (olecranal, cubital)

- Forearm (antebrachial)

- Wrist (carpal)

- Hand (manual)

- Thumb (pollex)

- Palm (palmar, volar)

- Back of hand (dorsum)

- Fingers (digital, phalangeal)

- Lower extremity

- Thigh (femoral) Knee

- Knee

- Anterior surface (patellar)

- Posterior surface (popliteal)

- Leg (crural)

- Calf (sural)

- Foot (pedal)

- Ankle (tarsal)

- Sole (plantar)

- Top of foot (dorsum)

- Heel (calcaneal)

- Toes (digital, phalangeal)

- Great toe (hallux)

Media Attributions

- U01-010 anatomical position © Wade, Alexia is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U01-011 directional terms diagram © Wade, Alexia is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U01-012 directional terms table © Bizell, Lizz is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U01-013 planes of section overview © Wade, Alexia is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U01-014 sagittal plane diagram © Wade, Alexia is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U01-015 transverse horizontal plane diagram © Wade, Alexia is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U01-016 frontal coronal plane diagram © Wade, Alexia is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U01-017 Anatomical planes in a human © Richfield, David and Häggström, Mikael is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U01-018 Coronal Plane © BruceBlaus is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- U01-019 Dorsal and Ventral Body cavities © Betts, J. Gordon; Young, Kelly A.; Wise, James A.; Johnson, Eddie; Poe, Brandon; Kruse, Dean H. Korol, Oksana; Johnson, Jody E.; Womble, Mark & DeSaix, Peter is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- U01-020 the Body cavities © Mysid is licensed under a Public Domain license

- U01-021 body cavities table © Bizell, Lizz is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U01-022 organs in quadrants table © Bizell, Lizz is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Regions and Quadrants of the Peritoneal Cavity © etts, J. Gordon; Young, Kelly A.; Wise, James A.; Johnson, Eddie; Poe, Brandon; Kruse, Dean H. Korol, Oksana; Johnson, Jody E.; Womble, Mark & DeSaix, Peter is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- U01-024 abdominopelvic regions table © Bizell, Lizz is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U01-025 Naming Parts of the Body © Betts, J. Gordon; Young, Kelly A.; Wise, James A.; Johnson, Eddie; Poe, Brandon; Kruse, Dean H. Korol, Oksana; Johnson, Jody E.; Womble, Mark & DeSaix, Peter is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license