33 When the Game of Pretend Becomes Real

An Examination of the Factors Causing Conspiracy Theories to Become Harmful

Rebecca Cook

Author Biography

Rebecca Cook, a freshman at Utah State University, is always working hard to exceed. As a full-time student, she wants to major in social work to help her community and its members. She is the fourth of five kids and loves her family wholeheartedly. When she is not working or at school, you can find her reading, playing basketball, or playing games with friends and family.

Writing Reflection

Writing this essay, I learned a lot about what factors cause conspiracy theories to be harmful in our society. I chose this topic because many opinions greatly influence people, and I wanted to understand better how this is done. As I researched, I learned what factors lead to problems and how we can counter them and teach people to think critically. This is very important for people everywhere to learn.

This essay was composed in April 2024 and uses MLA documentation.

Birds aren’t real. Disney’s Frozen is a coverup. The moon landing was fake. We have all heard about these conspiracy theories and a thousand more. We laugh and joke about it, finding them entertaining and silly. But what about the theories that are a little more dangerous? Is the government hiding aliens in Area 51? Are top Democrats behind a child sex ring? What about COVID-19? Was it really an accident? Are the vaccines helpful or harmful? The theories themselves are not too dangerous, but the actions they spur people to take can have many negative consequences.

It can be easy to see how conspiracy theories are more than harmless little stories. But what exactly is it that leads people to action? What factors of conspiracy theories lead them to be harmful in American society? To address this question, this essay will discuss four primary factors: social media, mental health, deep-seated motivations, and how conspiracy theories are incorrigible.

Playing the Game

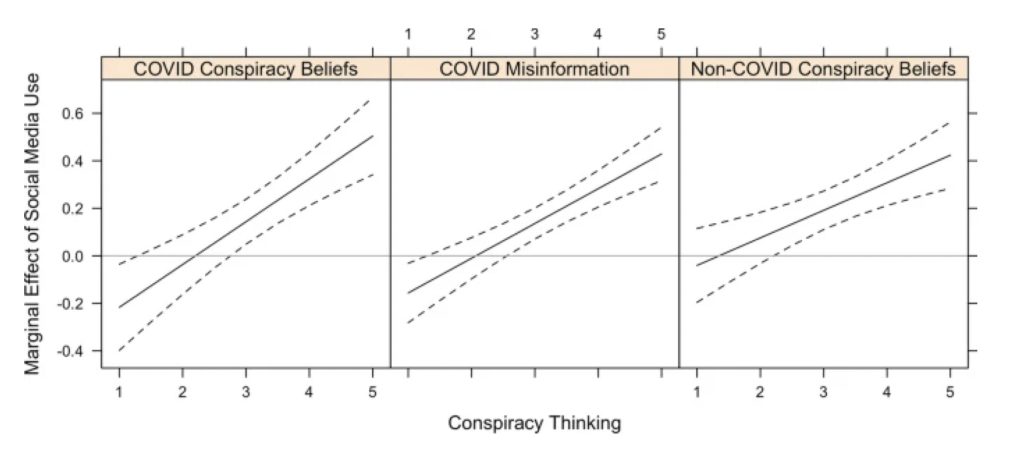

Social media use is the first and most widely known aspect that can lead to harmful behaviors due to conspiracy theories. In his research, Adam Enders gives the chart below, which helps us understand the correlation between social media use and the belief in conspiracy theories. Using COVID as an example, Enders shows a strong correlation between the use of social media and conspiracy thinking. His research discovered that the more people use social media, the more they think conspiratorially (Enders). This led to the question many people now ask: what about social media led to what seems like such a drastic change in conspiracy thinking?

The speed at which social media allows ideas to spread is one factor contributing to the prominence of conspiracy thinking in the last decades. Adding to the above chart (Figure 1), David Klepper, a reporter who has written for numerous papers, including The New Yorker, states, “Conspiracy theories have a long history in America, but now they can be fanned around the globe in seconds, amplified by social media, further eroding truth with a newfound destructive force” (Klepper). Algorithms in social media play a huge role in conspiracy theories’ ability to spread information quickly and efficiently. Algorithms are made to keep users on social media sites or apps for as long as possible, and so they work to generate engagement posts. As Colleen Tighe says, “VIRALITY EXISTS NOT TO REWARD THE USER’S INNATE TALENT OR PASSIONS BUT TO CONTINUE TO ENTICE OTHERS TO USE AN APP [AND] GENERATE MASSIVE PROFIT” (Tighe). Inflammatory theories and misinformation posts get high visibility because they get a lot of engagement, whether good or bad. High visibility and engagement expose more people to conspiracy theories. As ideas spread at a never-before-seen speed, people can find others who believe the same misinformation and conspiracies and feed on each other, repeating what the others say and strengthening their beliefs. Christine Mikhaeil explains, “We found that social media can help breed a shared identity toward conspiracy theory radicalization by acting as an echo chamber for such beliefs” (Mikhaeil). This “echo chamber” she refers to is confirmation bias at work. With social media and the internet, it has become increasingly easy for people to find “information” that supports any viewpoint they seek, even conspiracy theories that seem a little out there, like Amelia Earhart being eaten by giant crabs. These sources conclude that social media contributes to the dangerous behaviors resulting from conspiracy theories as they allow the ideas to spread rapidly.

The Players Are Stubborn

At this point, we might ask, why don’t we show conspiracy theorists the fault in their thinking? This question is answered by an assistant professor at Georgia State University when she states, “Instead of withering in the face of evidence that contradicts their beliefs, such groups often choose to deepen their commitment and this, in turn, can lead to radicalization” (Mikhaeil). This unwillingness to listen is the heart of the problem with the dangers of conspiracy theories. It is not the theories themselves but the stubbornness of the theorists. It is incredibly difficult to reason with someone and get them to set down their sword when they are told they are a bloodthirsty monster. In accordance with this observation, Ryoji Sato explains, “The problem with CTs [conspiracy theories] stems from the way in which the relevant belief is formed, and not from the falsity of the belief per se… CT beliefs are incorrigible in the sense that CT believers are not persuaded by rigorous empirical evidence or rational persuasion” (Sato).

For this reason, Mikhaeil points to the believers instead of the beliefs as a solution to this growing problem. Her theory is that the most important preventative action we can take as a society is developing the critical thinking skills of citizens so they know how to investigate whether sources are credible. As people do this, they are not fooled into believing a theory and questioning its reasons later, but they question the theory first and look for proof within it.

The Game Becomes Real

Melinda Moyer, a science journalist, shows us another side that leads people to conspiracy theories: “Experiments have revealed that feelings of anxiety make people think more conspiratorially… Feeling alienated or unwanted also seems to make conspiratorial thinking more attractive” (Moyer). Moyer pinpoints a specific group of people who are more susceptible to believing conspiracy theories. Concurring with this statement, Sato explains, “In an effort to make sense of the situation, CTs [conspiracy theories] outwardly explain why bad things happen, where the blame lies, and how to redress related injustices” (Sato). People begin turning to these beliefs instinctually and want to act on them so they can resolve the issues. This action they take, depending on the theory, can be dangerous because these theories often point fingers and make people or groups real live villains.

When people begin to take action to defend themselves due to these thoughts and ideas being pressed upon them, it, in turn, only makes the situation worse. Jon Green is a psychologist who was a founding member of the Suicide and Self-Injury Special Interest Group of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies and is the current president of the Men’s Mental and Physical Health Special Interest Group. In the article “Depressive Symptoms and Conspiracy Theories,” Green discusses people’s activity during the COVID-19 pandemic. His article aligns with Moyer’s ideas, which can be seen through the violent behavior and the “flouting of public health guidelines” (Green). He states,

These beliefs allow individuals to cope with stress, uncertainty, anxiety, and/or other conditions by providing narratives to explain threatening phenomena when other answers are difficult to generate. As such, it seems straightforward that the experience of depression correlates with holding conspiracy beliefs. (344)

Green not only assents to Moyer’s conclusions, but what is worse is these violent and unsafe behaviors often contribute to the depressing state of bad situations, perpetuating this cycle. People become stressed or depressed about a situation, and then they read something online telling them who to blame, so they react to that, which causes a negative impact. This negative impact makes others view the situation as only getting worse and worse, and so they slowly become depressed. This cycle goes round and round until someone works to stop the people from starting to take negative actions based on theories.

The Players Were Made This Way

Joseph Uscinski, a political scientist and professor, pioneered a new factor in the questions surrounding conspiracy theories and what influences believers when he states the most influential factors are people’s previous beliefs and ideologies. He uses recent studies to show how the traditional view of how conspiracy theories are adopted is not necessarily correct. The conventional belief was that someone would be exposed to misinformation, causing them to believe in a conspiracy theory, resulting in non-normative behavior. However, Uscinski argues that the studies done before the COVID-19 pandemic were sparse, and now that more data has been gathered on conspiracy theories (as they had a significant impact during the pandemic), there is a more likely explanation for what leads people to believe in conspiracy theories and therefore act irregular (Uscinski). He says that people’s ideologies and previous belief systems have a huge impact on how they perceive misinformation they are later exposed to. This idea brings up a whole new factor never truly considered before that can lead to non-normative or dangerous behavior based on conspiracy theories.

Uscinski states,

Well-evidenced theories of belief formation and media effects suggest that both beliefs in conspiracy theories and non-normative behaviors are the product of deep-seated motivations (e.g., identities, ideologies); these motivations are the foundational ingredients of belief formation that guide which information we integrate into our belief systems. (Uscinski)

This statement reevaluates the supposition that theories were pushed on people when they felt weak and instead explains how conspiracy theorists were struck by an idea they always believed in. The theories were not new ideas; they were concepts they always thought developed into words. Theorists were able to learn the name of what they always believed, and the theories took that belief and let it fester and grow until they were ready for action.

Conspiracy theories often appeal to people who feel situations must be changed or fixed. Describing work from a group of scientists at the University of Miami, Melinda Moyer states they “have shown that people who dislike the political party in power think more conspiratorially than those who support the controlling party” (Moyer). These findings affirm the new research presented by Uscinski. When people’s political parties are in control, their belief system is satisfied. If they are not, they begin to look toward sources that share conspiracy theories. They see these theories as not “theories” so much as what they always knew was true. The conspiracy theories motivate them to “fix” what is wrong, leading them to abnormal behavior that is sometimes dangerous. An example of this could be seen in the storming of the White House on January 6, 2021. The people involved shared a similar belief system: that the Republican Party and former president Donald Trump should remain in charge. They didn’t trust Democrats in much of anything, let alone running the country. So when rumors and theories started spreading that the election had been “rigged,” it was easy for them to see this and rationalize it as what they always thought since it affirmed the belief that “democrats are untrustworthy.” This shared belief, paired with the narrative about the election, led them to severe and violent actions in a desperate attempt to gain people’s attention to this problem and “fix” it.

Uscinski proposes a greater emphasis on conspiracy believers rather than conspiracy theories. He emphasizes the need for more research with a focus on the theorists and highlights that now is the ideal time to do this. Moyer also advocates for this need as new information confirms this idea every day.

The Winner

As we examine these four main factors that lead to harmful behaviors, the question turns to whether there is a solution. Many people have offered ideas, but the range is wide, and what might really work has yet to be thoroughly researched. However, I agree with Joseph Uscinski’s urging for more research to be done now that we have more access to tangible data and Christine Mikhaeil’s advice on focusing more on the conspiracy theorists rather than the theories themselves. As more research is done, we might teach our society to develop high levels of critical thinking, which would help solve this problem and benefit society as a whole. An important piece that must be considered is finding a way for our society to provide the emotional comfort theorists find in their theories. It is essential to consider where sources are coming from and what someone could gain from specific theories. Doing this will help our society push back on conspiracy theories and their harmful consequences.

Works Cited

Enders, Adam M., et al. “The Relationship between Social Media Use and Beliefs in Conspiracy Theories and Misinformation – Political Behavior.” SpringerLink, Springer US, 7 July 2021, link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11109-021-09734-6.

Green, Jon, et al. “Depressive Symptoms and Conspiracy Beliefs.” Applied Cognitive Psychology, Nov. 2022. EBSCOhost, https://doi-org.dist.lib.usu.edu/10.1002/acp.4011.

Klepper, David. “Grave Peril of Digital Conspiracy Theories: ‘What Happens When No One Believes Anything Anymore?’” AP News, AP News, 31 Jan. 2024, apnews.com/article/dangers-of-digital-conspiracy-theories-ec21024be1ed377a35fb235d9fa2af36.

Mikhaeil, Christine Abdalla, and The Conversation US. “The 4 Stages of Conspiracy Theory Escalation on Social Media.” Scientific American, 20 Feb. 2024, www.scientificamerican.com/article/conspiracy-theories-how-social-media-can-help-them-spread-and-even-spark-violence/.

Moyer, Melinda Wenner. “People Drawn to Conspiracy Theories Share a Cluster of Psychological Features.” Scientific American, 20 Feb. 2024, www.scientificamerican.com/article/people-drawn-to-conspiracy-theories-share-a-cluster-of-psychological-features/.

Sato, Ryoji. “The Rabbit-Hole of Conspiracy Theories: An Analysis from the Perspective of the Free Energy Principle.” Philosophical Psychology, vol. 36, no. 6, Aug. 2023, pp. 1160–81. EBSCOhost, https://doi-org.dist.lib.usu.edu/10.1080/09515089.2023.2210161.

Tighe, Colleen. “The Algorithm Oligarchy.” Nation, vol. 317, no. 13, Dec. 2023, pp. 22–25. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=asn&AN=174049877&site=ehost-live.

Uscinski, Joseph, et al. “Cause and Effect: On the Antecedents and Consequences of Conspiracy Theory Beliefs.” Current Opinion in Psychology, vol. 47, Oct. 2022. EBSCOhost, https://doi-org.dist.lib.usu.edu/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101364.