60 Language of the Canyon

Lauren McKinnon

This essay was composed in August 2021. Lauren McKinnon was a Graduate Instructor (2021-2023) and the Graduate Assistant Director of Composition (2022-2023) at USU’s Department of English. She graduated with her Master’s in English with an emphasis in Creative Writing in 2023.

BEFORE MORNING SUN HAS WARMED the canyon orange, a group of five college students carrying ropes arrives at a cliff edge.

“Is this our first wrap?” I ask, peering over the edge. The drop is only about thirty feet, with sandstone walls sliding into a dry pothole, but the exposure is dangerous. The rock has been carved by flash floods, making it smooth and erasing any potential foot or handholds.

“Dude, we could totally down climb that,” my friend McKay says. I exchange looks with the group, including two wide-eyed college students who have never been canyoneering before. Looking back at the drop, I say, “Better safe than sorry. I can see the bolts right over there—will someone check the webbing?” The vernacular is lost on the new members of the canyoneering club, but my husband, who is president of the club, always takes time to show new members what the webbing is and how to identify if it needs to be replaced. As we continue through the canyon, I listen to him explain how to repel, the phrases we use to call to each other throughout the canyon to let the group know we are safe, and other necessary skills for the sport.

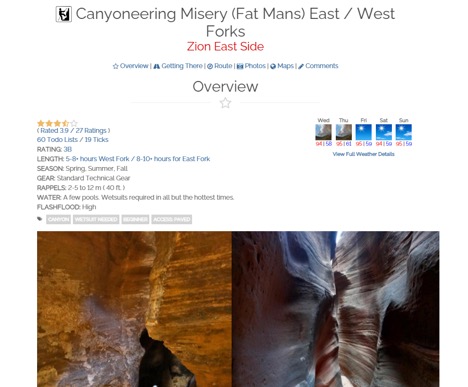

Canyoneering is a discourse community I am actively involved in. Canyoneering is the exploration of slot canyons, using tactical gear to descend and navigate natural obstacles, such as cliff faces, making this sport particularly prominent within the natural geography of southern Utah. To access canyons, one must collect online information conduct research prior to the trip, which requires collecting online information referred to as “beta.” Beta is used to determine the skill levels necessary for completing a canyon, the obstacles and terrain you may encounter, as well as GPS coordinates you may refer to. Beta is published online by previous canyoners, and successful canyoneering depends entirely on the ethos of the author publishing beta, the logos of the route described, and a firm understanding in canyoneering discourse. For this essay, I will be referring to beta published online regarding Misery, a popular canyoneering route in Zion National Park.

When analyzing beta, I am betting my life and the lives of my friends on the author’s credibility, which is the ethos of the document. To confirm credibility, you must always refer to when beta was published. By analyzing how recent the beta was published, along with other canyoners most recent comments, canyoners can determine whether the route has been naturally altered past the point of safety. Flash floods, recent rain, forest fires, and broken bolts can all affect the safety of a route, so it is important to receive the most updated and relevant information from sources that are reliable. Most of the times, beta is accurate, however; there have been times rappels are inaccurately measured, in which case, it is important to have extra ropes and the skills necessary to save yourself. For clarification—rappelling is the act of descending cliff faces using tactical gear such as ropes, harnesses, and belay devices. Rappels can be anywhere from ten to three hundred feet high.

Furthermore, beta also uses logos to communicate the difficulty of canyoneering routes. For this example, I am using beta from a website called Road Trip Ryan, a common canyoneering site. The route we are looking at is called Misery. The beta includes basic logistics to help readers understand the terrain of the canyon including how long the canyon may take to complete, how many miles it is, what kind of gear to bring, how many rappels there are, as well as primary resource photos which show accurate footage of what to expect in the canyon.

When analyzing beta, unless readers have a background knowledge on canyoneering, the lexicon of the document will be confusing. The first information noted is the canyon rating. Canyons are rated alphabetically from A to C based on how much water you will encounter and on a number scale from 1 to 4 based on how difficult the terrain is. Roman numerals may also be used to base how long the canyon will take, and finally, risk designation is rated by ratings like cinematic movies: PG, R, and X. As a new canyoner, analyzing beta may feel a bit like decoding nonsense. It is important to refer to other online sources or experienced canyoners if the language causes any confusion, otherwise, your life and the life of your group is at risk. The unfamiliar lexicon used in beta may either encourage those not actively involved in this discourse community to seek help, or worse, forego prior research and attempt a canyon without proper preparation. There have been many times I have interacted with individuals who are newer to the sport, who are afraid of seeming like a “gumby,” which is a derogatory term used in the community to describe someone who is less knowledgeable or cannot keep a quick pace. The shame associated with this term prevents some canyoners from even trying to understand beta because it may be overwhelming to understand. Oftentimes, this results in overconfident facades which lead to injury as underprepared individuals enter a canyon without the proper skills, gear, or understanding of what terrain they may encounter.

The existence of accurate beta is imperative to the survival of canyoneering as a sport and community. The publishing of accurate beta depends on the logos and ethos of the document, and the vernacular of the community may be exclusive to those unfamiliar with the sport, or worse, encourage compensating attitudes which lead to injury. Overall, canyoneering is a thrilling sport most fun when shared with others, so it is important to explain terminology and skillsets to those interested in learning.