39 Family History: Source of Connection

Karina Dyches

Author Biography

Karina Dyches has loved writing since before she can remember. It is her favorite art medium and method of communication. When not writing or reading old classical novels, she loves to spend time with her family and friends, design things digitally, and work as an architectural drafter. You’ll probably see her wandering around campus with her walker and her service dog, Daisy, for the next decade as she pursues a Bachelor’s degree in Creative Writing.

Writing Reflection

For this essay, our entire class had to use “Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation” as a source. So, as I read it, I thought to myself, “What helps me the most when I feel lonely?” The answer is my amazing family and remembering those who’ve gone before. This essay was born out of that passion and shares some of the scientific benefits supporting it, as well as some of the negative responses to it.

This essay was composed in April 2024 and uses MLA documentation.

According to the Office of the Surgeon General, we are living in an epidemic. Surprise! But, unlike the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020, this is not an epidemic they can fix by telling us all to sit tight and stay home. No, in fact, that would make this particular epidemic worse. You see, we are living in an “epidemic of loneliness and social isolation.” It is both widespread, affecting approximately half of U.S. adults as they report experiencing loneliness, and concerning, as the lack of social connection can increase the risk for premature death as much as smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day does. The Office of the Surgeon General, in their 80-page Advisory on the subject, says, “We are called to build a movement to mend the social fabric of our nation. It will take all of us—individuals and families, schools and workplaces, health care and public health systems, technology companies, governments, faith organizations, and communities—working together to destigmatize loneliness and change our cultural and policy response to it. … Each of us can start now, in our own lives, by strengthening our connections and relationships” (Office of the Surgeon General, 5). There are many ways, obviously, to participate in this movement. However, as family is a fundamental unit of society, it stands to reason that our relationships with our own families would touch us fundamentally.

Nurturing these threads of connection with our family members can shape our identity and strengthen our sense of worth in life. This can be true even if those family members are no longer with us. Family history, also known as genealogy work, is the act of connecting with those who have gone before. As such, it can show us our role in the great chain of human life. We all have a family history – forefathers and foremothers, progenitors, and linear relatives – but how many of us know that? How many of us actually tap into this amazing buffer against loneliness and isolation? Not as many as should. Yet, I believe, it is a vital aspect of how one views themselves. Knowing your family history and genealogy fosters a sense of connection and serves as a buffer against loneliness and isolation.

In a study conducted with university students in their late adolescent years at three universities across the United States “explor[ing] the relationship between psychological and sociological components of adolescent identity development and family history knowledge,” researchers found that knowing your family history helps with relatedness/belonging, conviction/commitment to ideals, and healthy differentiation, all crucial steps in healthy identity development. Data was collected on participants’ relationships with their parents, identity development processes, and family history knowledge using the “Do You Know?” (DYK) scale (Haydon). The DYK scale is a questionnaire with 20 questions that inquire if participants know such information as where their parents were born, how their parents met, or even what was happening the day they themselves were born. None of the questions require family history knowledge from beyond the lives of parents and grandparents, showing that genealogical research doesn’t need to be extensive, or even intentional, to be effective. Just story time between a parent and a child can bolster a child’s sense of identity for the rest of their life. Robyn Fivush, who conducted a similar study on adolescents 14 to 16 years old, wrote, “Families that share stories, stories about parents and grandparents, about triumphs and failures, provide powerful models for children. Children understand who they are in the world not only through their individual experience, but through the filters of family stories that provide a sense of identity through historical time” (2). She continued, “we may be looking at a form of observational or vicarious learning” (Fivush 7). This is a powerful tool for those wishing to inspire more confidence in their children or, conversely, in themselves. As descendants, we can ask our parents, grandparents, and other older family members to share their defining memories and heartwarming anecdotes.

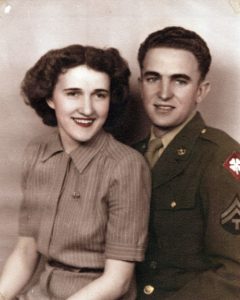

I grew up in a family that abounds in such storytelling. Figure 1 shows a young couple, seated for a professional photograph. This picture may look just like any other G.I. Joe and his girl, but, to me, I see my great-grandparents in a similar stage of life as me. It was taken when Joe Hilton (yes, his name really is Joe) was home for furlough towards the end of basic training in World War II and enjoying time with his parents, siblings, extended family, neighbors, friends, and, of course, his sweetheart before being shipped out overseas. Wanting to make it memorable, he took his girl, Joan Walker (whom he later married), to get a picture taken together professionally. What makes this story unique is, years and years later, this photo reminded Joe of how he had gotten a cold sore on his bottom lip right before furlough. He was so mad about the cold sore that he’d had the photographer “touch up” the photo! This is just one of the many, many stories that Grandpa Joe, who died last year at 99, told me growing up. His stories grounded me and gave me a window into the past, showing me how much human nature doesn’t change.

Research also suggests that learning about our family history can greatly affect how we live our lives. It makes us consider the legacy we want to leave behind and can direct our professional, educational, and personal choices. For example, a young high school dropout reenrolled in school with the intent to pursue studies in marketing after discovering that his deceased uncle had been a very successful marketer. Another young man, reintroduced to stories about his grandfather’s experiences as a soldier in World War II, chose to pursue a career in the armed forces (Haydon). A young woman called her little son Isaac, not realizing until she saw the family tree that her great-great-grandfather had been called Isaac (Kramer 389). Learning about our predecessors can point out interests we didn’t realize we had. It can provide guidance on which path we should take in our lives and help us see the meaning and legacy we are leaving behind us.

There are other widely accepted benefits to knowing your family history that are harder to prove scientifically. These benefits include resilience (when life gets hard, we have a whole reservoir of stories and examples to fall back on), greater connection with others (both living and dead since we can better see how we’re all connected), compassion and selflessness (as we are more familiar with others’ hard experiences), improved health choices (we know what we are genetically susceptible to), and enhanced self-worth (their challenges, triumphs, and sacrifices made us possible) (Coleman; “5 Benefits of Knowing Your Family History”). Who wouldn’t want these qualities in their life?

The Mass Observation Project, a social research project based at the University of Sussex, which issued themed “writing tasks” about aspects of everyday life to anonymous volunteer writers, asked in 2009, “why family history was popular, who does it, what questions it answers, which groups are most interested in it, the relationship between family history and history more generally, and how people ‘do’ family history” (Kramer 384). Responses came pouring in, varying so considerably that researchers concluded, “Rather than exposing the fragility of family ties, the passion for, as well as the hostility against, genealogy reveals that individual identity remains firmly anchored to, and rooted within, kinship networks, and that kinship itself remains fascinating and central to personal lives” (Kramer 392-393). This passion is evident throughout the world and brings thousands of people together annually. Hundreds of family reunions take place, whether formally or informally, each summer. Many small towns, growing up out of closely knit common heritage, celebrate their history with “Hometown Days” or something similarly named. A quick search for “genealogical conferences” brings up so many results that it seems one could be at a conference nearly all the time all year round. RootsTech – “The Largest Genealogy Conference in the World,” hosted by FamilySearch, draws hundreds of thousands of participants both virtually and in-person every March. Personally, I love doing family history research with my living family members, especially my grandmothers. Genealogy and family history pulls people together in a deeply connecting and enthusiastic way. It has often been called addicting – in the best way. There is an undeniable thrill when you are on a roll with genealogical research. Sharing that with someone else makes it even more exhilarating.

However, the quote above mentions hostility as well as passion. How could this be? If family history is so beneficial, why would it raise hostility? Negative responses to the Mass Observation Project’s query vary from skeptical at best to downright grouchy. Some thought family history research was just a way of stroking one’s ego. One woman wrote, “Sometime [sic] I think people may do the research to flatter themselves – they love to find traits in their ancestor that they share.” The opinion here is that the study of family history is ultimately an exploration of self and therefore, a selfish endeavor, not focused on the past at all (Kramer 386). While this assessment is sometimes true, it can be avoided. Like most things in life, family history is best approached with an open mind. Inevitably, unfortunate or disagreeable facts will come to light, but if we accept them and move on, we will be stronger for it.

Other people expressed a desire to focus rather on living family members. “I just want to keep all the family together,” wrote one woman in her 50s. “I am interested in my living relations more than the distant past” (Kramer 386). This is a valid concern, but the two activities are not mutually exclusive. Current family ties become stronger as we explore the past together. The connection between us grows with every common experience we share, and, as one study discovered, “family stories… were related to child well-being [more than o]ther kinds of narratives… such as stories of the [family members’] day” (Fivush 2). Simply sharing memories of our shared past, over and over again, increases the likelihood of forging unbreakable family bonds across the boundaries of time and space.

The most heavily heartbreaking reason used against family history research is because it might result in painful consequences. There were concerns about genealogical enquiry’s potential to uncover long-buried, deliberately concealed secrets, including questions of parentage. “In these contexts,” the conclusion was that “it seemed better to leave sleeping dogs lie: forgetting here is itself a deliberate act, a desire not to know” (Kramer 387). This is an extremely difficult situation to be in. A desire not to know where you came from for fear of upsetting a delicate balance is a very valid emotion and should be respected. In these cases, as well as cases of adoption, disownment, or similar circumstances, the idea of having a “found family” can apply in the past like it does in the present. History is full of heroes, and we can admire them whether we are related to them or not.

On a more scientific note, one study concluded that “Ancestral information did not increase social connection or life meaning.” However, the data collected only compared those who had received DNA test results and those who had not. Nothing was collected on those who knew family stories, – in fact, those who did were disqualified from participating (Kim). While an intriguing research angle, the results weren’t very surprising. In a keynote address at RootsTech, David Isay, the founder and president of StoryCorps, said, “The power of authentic stories, of stories told from the heart, of real honest stories, the power to build bridges between people, bridges of understanding, is infinite.” He also quoted Mary Lou Kownacki in saying, “It’s impossible not to love someone whose story you’ve heard” (FamilySearch). Stories are always what interest and connect us to another person, and it makes sense that applies to family history as well. Learning your family history stories has tremendous potential to bolster one’s sense of identity and connection and buffer against loneliness and isolation.

So, how can you begin? Simply. The next time you sit down to a meal with your family, invite them on a trip down memory lane with you. Talk about memories you all share (like family vacations) or ask about your parents’ childhoods. If that’s still overwhelming, perhaps use the 20 questions in the DYK scale (found here on PsychologyToday) as a launchpad. These simple prompts can unearth some great stories, I’m sure. If you want more stories, ask your grandparents about their lives – their memories and their ambitions, or their homes – the paintings on their walls and the curios on their mantels. Doing something simple like this will benefit everyone involved.

If visiting your family is off the table for now, consider opening a FamilySearch account. Their shared online family tree is easy to use (once you’ve connected yourself and all other living ancestors – i.e., parents or grandparents, etc.) and each individual has a very accessible “Memories” section, where users can share photos, stories, and audio recordings of deceased family members. If you try it out, you just might find some hidden treasures so get on and look around!

And, finally, pay it forward. Share the stories that mean the most to you with your family, especially those younger than you, whether it be as a sibling, cousin, aunt/uncle, or parent. Or you could record those stories in a journal or video collection for future use. The possibilities are endless.

In this way, we can all participate in the “movement to mend the social fabric of our nation” (Office of the Surgeon General, 5) and end the epidemic plaguing us.

Works Cited

5 Benefits of Knowing Your Family History. https://selecthealth.org/blog/2019/08/5-benefits-of-knowing-your-family-history. Accessed 30 Mar. 2024.

Coleman, Rachel. “Why We Need Family History Now More Than Ever • FamilySearch.” FamilySearch, 26 Sept. 2017, https://www.familysearch.org/en/blog/why-we-need-family-history-now-more-than-ever.

FamilySearch. RootsTech 2016 | David Isay (Keynote). 2016. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YOeG0V6BbfE.

Fivush, Robyn, Marshall Duke, and Jennifer G. Bohanek. “’Do You Know…’ The Power of Family History in Adolescent Identity and Well-being.” National Council on Public History, 23 Feb. 2010, https://ncph.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/The-power-of-family-history-in-adolescent-identity.pdf.

Haydon, Clive G., et al. “Identity Development and Its Relationship to Family History Knowledge among Late Adolescents.” Genealogy (2313-5778), vol. 7, no. 1, Mar. 2023, p. 13. EBSCOhost, https://doi-org.dist.lib.usu.edu/10.3390/genealogy7010013.

Kim, Tami, et al. “Effects of Ancestral Information on Social Connectedness and Life Meaning.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, vol. 111, Mar. 2024, p. 104563. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2023.104563.

Kramer, Anne-Marie. “Kinship, Affinity and Connectedness: Exploring the Role of Genealogy in Personal Lives.” Sociology, vol. 45, no. 3, June 2011, pp. 379–95. EBSCOhost, https://doi-org.dist.lib.usu.edu/10.1177/0038038511399622.

Office of the Surgeon General. “Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation.” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-social-connection-advisory.pdf, 2023.