41 Addressing Factors That Impact Underreporting of Men Who Experience Sexual Assault

Alexis Klein

Writer Biography

Alexis Klein is a freshman at Utah State. She is originally from Perth, Australia and moved to the United States at six years old. She loves composing music and playing the piano. She is majoring in Communicative Disorders with minors in Human Development and Psychology. Alexis hopes to one day become a Speech Scientist and work on a cure for stutters.

Writing Reflection

Over the past couple of years, I have become obsessed with the TV show Law and Order: Special Victims Unit. I noticed an underrepresentation in men who are victims of sexual assault on the show, and even when they are portrayed, they are often portrayed in negative way, heavy with stereotypes. I wanted to explore how societal and environmental factors impact men reporting instances of sexual assault.

This essay was composed in December 2022 and uses MLA documentation.

Please be advised, this essay discusses assault, rape, and abuse. If you are experiencing or have experienced sexual assault and/or sexual abuse, the Rape, Incest & Abuse National Network (RAINN) offers a hotline where you can be connected to a trained staff member who can talk you through your experiences, refer you to local resources, provide you with information about laws in your community, and walk you through the next steps in your journey. This hotline is accessible by dialing 800.656.HOPE (4673).

Resources at USU:

- Office of Equity: Report sexual misconduct to USU’s Office of Equity. This website links you to several reporting options, including an online reporting form, email, or phone.

- Sexual Assault and Anti-Violence Information Office (SAAVI): SAAVI can help you report an assault, obtain a forensic exam, accompany you to the police, and answer questions about sexual violence, intimate-partner violence, or stalking.

- Campus Resources: Find links to access trained advocates, counseling services, Title IX Coordinator, and police.

Additional Resources:

- SafeUT (an app that connects you to licensed counselors)

- CAPSA (Nonprofit domestic violence, sexual abuse, and rape recovery center serving Cache County and the Bear Lake area. They provide support services for women, men, and children impacted by abuse. All of their services are FREE and confidential.)

- National Sexual Assault Hotline- 1-800-656-4673. Open 24 hours

- 1in6.org (support for men who have experienced sexual assault)

- RAINN hotline, 800-656-HOPE

- National Suicide Hotline: Call 988 or 1-800-HOPE

Men who are sexually assaulted often face a slew of stereotypes and stigmas that sometimes even they believe (Hammond et al). They might be ridiculed for not defending themselves, accused of liking it, and derided for not disclosing it sooner (1in6.org, RAINN). Three main factors contribute to underreporting abuse: sociocultural beliefs, perceptions of police intervention, and a lack of education surrounding sexual abuse. Before exploring these factors, it is best to start with a definition of sexual assault. In this essay, the terms assault, abuse, molestation and rape may be used interchangeably, depending on what the source has labeled. Statistics on the prevalence of this assault vary based on definition. The main statistic used for this essay comes from the non-profit organization, 1 in 6, which states that at least 1 in 6 men are sexually assaulted in their lifetimes (1in6.org). Sexual assault refers to any sexual assertion of power; this ranges from unwanted touching to rape (1in6.org). It may refer to a one-time event, or many events over the course of many years. For the purposes of this essay, that definition will be used when speaking about victims. Each person’s story is different, and the nuances of what constitutes abuse is important, but defining abuse is not the primary emphasis of this essay. In addition, it is important to note that transgender men have endured disturbingly higher rates of sexual abuse compared to cisgender men. To read more, refer to the study, “Gender Identity Disparities in Criminal Victimization: National Crime Victimization Survey, 2017-2018” (Williams Institute and Flores et al.).

The first factor that contributes to underreporting of abuse are sociocultural beliefs that lead to stereotypes (Rakovec-Felser). For example, often when a man is sexually assaulted by another man, it is assumed that the victim, perpetrator, or both are gay, and this assumption can come with negative and prejudicial associations that can silence victims and impact how their assault is investigated if they do report it. Regardless of the perpetrator’s or victim’s orientation, the sexual abuse is often about power, not sex (Hammond et al.). In many cases, abusers want to assert dominance over their victims. However, myths that link homosexuality to abuse are all too common. In one case, researchers reported that the therapist of a victim of sexual abuse told him, “I hope you are not one of those homosexuals who are going to waste my time telling me about imagined sexual abuse” (qtd. in Cook and Ellis). Harmful rhetoric and stereotypes like these can prevent men from disclosing and reporting instances of sexual assault.

When women are the perpetrators, stereotypes can misrepresent the men involved and prevent them from reporting their assault or impact if they are believed when they do report it. One false belief is that the victim is weak for not fighting back. However, a 2014 study showed that men were often afraid to report sexual violence committed by women because they were afraid of getting in trouble from the police (Rakovec-Felser). Because men are often perceived as stronger, they may find it embarrassing to report being assaulted by a woman. Another common myth is that the man should have “enjoyed” the assault or that they are “lucky” (NoMore.org). Although the belief isn’t as common as perhaps it once was, some still falsely believe that sexual assault can’t be committed by a woman to a man, and if it did happen, something must be wrong with the victim (Hammond et al.).

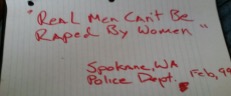

Another factor that can impact men reporting sexual assault is that police are often perceived as not believing victims. This is not to say that men are never believed; however, some men have had experiences with not being believed or have even been arrested. In Image 1, one man wrote and photographed words he reports the police department said to him when he reported his sexual assault; the sign reads, “Real men can’t be raped by women. Spokane, WA Police Dept. Feb, 99” (Project Unbreakable). This image is a part of Project Unbreakable, an online website where people can send in photographs of what perpetrators or others have said to them about their rape (Project Unbreakable). This shows that men are often not believed or think they won’t be believed by police. However, the perceivability of police believing victims is different depending on if the perpetrators is a man or woman. In a 2016 survey of men, both victims and non-victims, 59% of men said they “agreed” or “strongly agreed” with the following statement, “The police will not take it seriously if a woman assaults a man.” (Hammond et al). Of the remaining 41% of participants, 21% of the participants said that they were “unsure.” However, that number for perpetrators who are men was only 18%, with an additional 22% being unsure. The researchers also reported that among all of the statements asked to the group, that was the only statement that received high levels of agreement, meaning that a majority of the men agreed that police tend not to believe men who have experienced assault by a woman. This could contribute to men underreporting because if they feel they won’t be believed by authority figures, they may not want to get in more trouble by reporting.

Sometimes men who are victims of IPV, or Intimate Partner Violence, endure secondary abuse from those who are meant to support them. For example, in a study of men who have been victims of IPV in heterosexual relationships, “Participants also reported secondary abusive experiences, with police and other support services responding with ridicule, doubt, indifference, and victim arrest” (Walker). This point relates to myths about sexual abuse perpetrated by women; people don’t believe that a woman could hurt a man, and in some cases, the victim is even arrested. Stories like these–of men being arrested in cases where they have been assaulted–can lead to men not thinking that they will not be believed by the police, which impacts them wanting to report sexual abuse.

The final factor that could impact reporting among men is the lack of education about sexual assault. Because some sociocultural beliefs are still held regarding facets of sexual assault, and because police and other authority figures sometimes don’t take men seriously, education about sexual assault is limited. The lack of education that leads to underreporting can be traced to adolescence. According to Ashley Voogt, a researcher who conducted a meta-analysis of perceived credibility of victims of sexual assault, “adolescence appears to be age during which the role of gender stereotypes start to play an increasingly influential role” (Voogt). Children start junior high and high school in adolescence, and they begin to interact more with people of different genders. When there isn’t adequate education about sexual abuse in adolescence, these stereotypes continue to be enforced instead of dispelled.

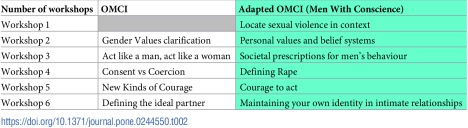

However, education about sexual abuse can help change men’s perspectives. In one 2021 study, researchers held workshops for college students in South Africa (de Villiers et al.). These workshops had the goal of informing college students about sexual assault and rape. After the first set of workshops, the researchers adapted the workshops based on the sessions, which is what the green portion of Table 1 displays. Although the workshops were geared to minimizing male perpetrators and violence, the participants still learned to dispel myths they held about sexual assault and wanted to open up the conversation. One participant stated that “after I attended the workshops, I realized how much we needed to start … like discussion groups or like a sexual violence forum on campus” (de Villiers et al.).

Another participant stated that “maybe we don’t want to face up to it [because] it’s so scary … [because] it can happen to anyone” (qtd. in de Villiers et al.). He also stated that “I think if we as leaders can share our ideas and thoughts with others, like we did in the workshops … I think that will help make sexual violence a less scary issue to engage with” (qtd. in de Villiers et al.). These men not only learned about sexual assault, but changed their mindsets on sexual assault and thought about why they were hesitant to speak about it. This study shows how even a few workshops can increase men’s awareness of sexual assault, and could help them potentially identify sexual assault in their environment.

What about older adults? In the case of “Bill,” a 45-year-old man suffering from marriage problems and anger issues, he didn’t know that experiences he had endured previously were actually sexual abuse. When asked, he didn’t report having traumatic events in his life, but according to researchers, his reporting of it seemed to downplay the impact; he “noted that some ‘funny-business’ had occurred” (Cook and Ellis). Because “Bill” was not educated on what sexual abuse or assault was, he did not have the correct way to label his assault and didn’t realize that he was a victim. This likely contributed to the intimacy and anger issues seen later in life.

In addition to a lack of education, men often don’t disclose abuse or report it because of shame. One study found that men typically wait 20-25 years after the event to report it (Cook and Ellis). In an op-ed from ESPN, Alec Govi, a former college athlete, tells of being molested by his coach. He didn’t want to report it because he felt ashamed. Govi states that he “couldn’t understand why I trusted him and allowed him to do what he did over and over” and that “the shame…was unbearable” (Govi). For this reason, he didn’t seek help or even disclose until another survivor of abuse perpetrated by the coach reached out to him.

In Govi’s case, he might not have reported the abuse had he not connected with others and became educated on sexual abuse. In the case of “Bill,” he never sought help or reported the sexual abuse because he didn’t know how to label it. And for the anonymous person who reported to the Spokane Police Department in Image 1, his claim was dismissed on the basis of sociocultural beliefs. What can happen when abuse isn’t reported until 20-25 years later? Barriers in each step of a victim of sexual assault’s journey can impede help-seeking, and there are lifelong consequences for this. Some of those consequences are linked to sexual function, including erectile dysfunction, low self-esteem, and low sex drive (Cook and Ellis). Other consequences can impair their ability to work and live life happily. Men who have been assaulted are at a much higher risk for suicidal thoughts and behaviors as well as alcohol abuse, problems in relationships, and underachieving at work (1in6.org).

Many factors can prevent men from reporting or disclosing their experiences. Those factors include sociocultural beliefs that surround victims and perpetrators, perceptions of being believed by police, and a lack of education on sexual assault. And when men report sexual abuse, they may be faced with disbelief from the police, support systems, therapists, or even society as a whole. People who don’t seek help for sexual assault are at a higher risk for impaired sexual function as well as the ability to work and have typical relationships. These factors impact not only reporting, but also the rest of the victim’s life. By being more aware of these factors, it can help men to feel more comfortable in reporting instances of sexual assault and receive help.

Resources for Victims of Sexual Assault

- National Sexual Assault Hotline- 1-800-656-4673. Open 24 hours

- 1in6.org

- RAINN.org

- National Suicide Hotline: Call 988 or 1-800-HOPE

Works Cited

“The 1 in 6 Statistic – Sexual Abuse and Assault of Boys and Men.” 1in6, 19 July 2018, https://1in6.org/get-information/the-1-in-6-statistic/.

Flores, Andrew R., et al. “Gender Identity Disparities in Criminal Victimization: National Crime Victimization Survey, 2017-2018.” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 111, no. 4, 2021, pp. 726-729. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2020.306099.

Govi, Alec. “Op-Ed: Building Back Trust and Finding My Voice after Sexual Abuse.” Daily Bruin, https://dailybruin.com/2022/08/28/op-ed-building-back-trust-and-finding-my-voice-after -sexual-abuse. Accessed 20 November 2022.

Hammond, Laura, et al. “Perceptions of Male Rape and Sexual Assault in a Male Sample from the United Kingdom: Barriers to Reporting and the Impacts of Victimization.” Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling, vol. 14, no. 2, 2016, pp. 133–149., https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.1462.

Joan M. Cook, PhD; Amy E. Ellis. “The Other #Metoo: Male Sexual Abuse Survivors.” Psychiatric Times, MJH Life Sciences, https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/other-me-too-male-sexual-abuse-survivors.

Rakovec-Felser, Zlatka. “Domestic Violence and Abuse in Intimate Relationship from Public Health Perspective.” Health Psychology Research, vol. 2, no. 3, Sept. 2014, pp. 62–67. EBSCOhost, https://doi-org.dist.lib.usu.edu/10.4081/hpr.2014.1821. Accessed 20 November 2022.

“Transgender People over Four Times More Likely than Cisgender People to Be Victims of Violent Crime.” Williams Institute, 31 Mar. 2021, https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/press/ncvs-trans-press-release/.

de Villiers T, Duma S, Abrahams N (2021) “As young men we have a role to play in preventing sexual violence”: Development and relevance of the men with conscience intervention to prevent sexual violence. PLoS ONE 16(1): e0244550. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244550.

Voogt, Ashmyra, et al. “The Impact of Extralegal Factors on Perceived Credibility of Child Victims of Sexual Assault.” Psychology, Crime & Law, vol. 26, no. 9, 2020, pp. 823–848., https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316x.2020.1742336.

Walker, Arlene, et al. “Male Victims of Female-Perpetrated Intimate Partner Violence, Help-Seeking, and Reporting Behaviors: A Qualitative Study.” Psychology of Men & Masculinities, vol. 21, no. 2, Apr. 2020, pp. 213–23. EBSCOhost, https://doi-org.dist.lib.usu.edu/10.1037/men0000222. Accessed 16 November 2022.