7 Scientific Support of Positive Dog Training Methods

Terese Durand

Terese Durand is currently going into her junior year at Utah State. Originally from San Jose, California, Terese came out to Utah hoping to achieve a bachelor’s degree in Animal Sciences during her time here. Terese is striving for admission into the vet program at UC Davis and hopes to one day become an Animal Veterinary Behaviorist and help owners of frightened, anxious animals achieve better quality of life for their pets.

Writing Reflection

In the summer semester break between my freshman and sophomore year, I impulsively went down to the Humane Society and bought a dog. Her name is Zara, and she was five months old at the time, and currently she is in training to be my service dog. When I first got her, I had no clue what I was doing. I had never raised a puppy before. Potty training was hard, and learning how to exercise a high-energy breed required me to change my lifestyle, and general training was very frustrating. I turned to the internet for help and realized just how easy it was to get lost in the maze of dog training myths and false truths. I trained her with strictly positive reinforcement only, but I saw how many others out there were training their dogs on negative reinforcement because they had never been shown anything to prove that they didn’t need to use those methods. I wrote this paper to provide solid, scientific proof of the effects of different training methods in order to help dispel some of the myths that new and experienced dog owners alike fall prey to.

This essay was composed in December 2022 and uses MLA documentation.

DOGS ARE ONE OF THE most popular pets in American households, with over sixty-nine million households in America owning at least one dog. The Best Friends Animal Society estimates that currently one hundred eight million dogs are owned across the country (“The State of Animal Welfare”). However, of the millions of Americans owning a dog, not all of them are aware of the differences in training techniques within the dog training industry and the possible harm they might be inflicting on their furry friend. As growing amounts of studies are making the connection between positive training methods and increased dog welfare widely known, it is the responsibility of every “pet parent” to choose the more humane option.

Of all the techniques and theories practiced today for training and behavior modification in dogs, the main methods of the industry can be simplified into two main categories: aversive training methods and positive reinforcement training methods. Aversive training methods are defined as anything designed to use fear, pain, or discomfort to force a dog to perform the desired behavior or stop the undesired behavior. This method can include the use of tools such as choke chains, prong collars, or electronic collars, or the use of other methods such as hitting, scolding, or dominance techniques such as “alpha rolls,” the act of forcefully rolling a dog onto its back in order to force submission and “correct” the unwanted behavior. Choke chains are chains that are used to apply pressure to the dog’s neck. This method is aversive when it is essentially used to strangle the dog in order to stop them from pulling. Prong collars are commonly used in order to prevent dogs from lunging and pulling. These collars work by applying sharp pressure into the circumference of the dog’s neck via prongs that are situated in pairs around the entirety of the collar.

Trainers who use these tools claim that to correctly fit a prong collar, it must sit directly behind the dog’s ears and under the throat latch, resting on the most sensitive area of a dog’s neck and on certain organs such as the thyroid and salivary glands. According to Jim Casey, a mechanical engineer quoted in a Pet Professional’s Guild letter, “A dog can pull against its leash/collar with more force than its own weight and can exert even more force if it gets a running start before it reaches the end of its leash. When a trainer is using this collar on a dog and snaps the leash to deliver a “correction,” that action has the potential to deliver well over 500 psi per prong simultaneously into the circumference of the dog’s neck. Considering a typical flat collar, an 80 pound dog can cause a contact force of approximately 5 pounds per square inch (psi) to be exerted on its neck. This force increases to 32 psi if a typical nylon choke collar is used and to an incredible 579 psi per prong if a typical prong collar is used. This represents over 100 times the force exerted on the dog’s neck compared to a typical flat collar” (qtd. in Steinker and Tudge 2). By this explanation, when a trainer is using this collar on a dog and snaps the leash to deliver a “correction,” that action has the potential to deliver well over 500 psi per prong simultaneously into the circumference of the dog’s neck. This greatly increases the risk of injury to the sensitive tissues on the underside of the dog’s neck as well as increasing the likelihood that these collars inflict large amounts of pain on the dogs that wear them.

Another of the most common tools used in aversive training is the electric collar. These collars have been branded by other terms such as “static” or “educator” collars in order to attempt to downplay the truth that these collars deliver an electric impulse into the sensitive tissues under the dog’s neck and cause the muscles to seize. Again, most trainers using these tools claim that to properly fit an electric collar it must rest on the underside of the dog’s neck with one prong on either side of the trachea and that the collar must be delivering a level of shock that the dog shows visible discomfort. This positioning allows for the electric impulse to be delivered to the most sensitive areas of the dog’s neck. For all of these tools, it is the stopping of the pressure or pain that is the reward. This method is the cornerstone of the aversive training technique.

Positive reinforcement training methods can be defined as any methods that focus on rewarding the desired behavior in order to increase the frequency that the behavior is voluntarily offered by the dog. This method can include the use of food rewards, toys, praise, and positive experiences such as greeting other dogs, greeting friendly strangers, sniffing interesting smells, or anything else that the dog enjoys. There are many reasons why dog owners should seek positive training methods, the first of which being the physical harm that is done to the dog when using the tools associated with negative reinforcement techniques. Prong and choke chains can cause serious harm to the dog’s neck, not only on the surface skin level but even underneath, damaging the thyroid and other organs that rest on the underside of the dog’s neck. According to an infographic supplied by the San Francisco ASPCA, some dogs have died from injuries caused by prong collars or choke chains (“What’s Wrong with the Prong?”).

While these tools are some of the equipment generally used in aversive training, they are not always used in a strictly harmful manner. Handlers of show dogs use chain collars when in the ring in order to communicate to the dog through the use of tension while allowing the judge to view the most amount of the dog as possible. The goal when using these collars is not to prevent the dog from pulling, but merely to use the slight tightening of the collar to communicate direction to the dog. These different uses for chain collars are just some examples of how tools can be used in different manners and that it is the philosophy behind the tool that matters.

An example of how tools can be used in either a positive or an aversive manner within a training philosophy is the methodology of LIMA. LIMA is an acronym for the phrase “Least Intrusive, Minimally Aversive” and is used to describe a trainer who uses the least intrusive and minimally aversive training strategy out of a set of humane and effective tactics that are likely to succeed in achieving the behavior change. LIMA adherence requires trainers to be educated and skilled in order to ensure that the least aversive procedure required is used when training the dog. LIMA is generally used by trainers helping owners with severely reactive dogs. Some of the tools that trainers recommend for their clients can include prong collars and e-collars, however, the use of these within the actual training is generally strictly limited. These are “last resort” or “emergency situation” tools, used only when the dog is not responding to other methods and there is a risk of harm to adults, children, or other animals. (“Least Intrusive”)

For the most part, shock is either limited to some of the lowest settings or restricted to only the vibration or beep, and that input is paired with a specific behavior that is antithetical to the unwanted behavior. This is what is known as “positive punishment”. Positive punishment is the application of an aversive stimulus in order to decrease the unwanted behavior, similarly to how shock and prong collars are used in aversive training. However, in LIMA the aversive stimulus is paired with redirecting the dog into a wanted behavior that cannot be completed while performing the unwanted behavior. An example would be when a trainer teaches a dog that a buzz or slight shock from the collar means to look to the handler for a treat. When the dog is focused on a trigger, such as another dog, and at risk of performing an unwanted behavior, like charging or barking, the handler would then use the collar to beep at, vibrate, or shock the dog. If trained correctly, the dog would then turn to look at the handler, looking away from the trigger and choosing to place themselves in a situation where they can no longer negatively react to their trigger. This both removes the risk of the dog attacking their trigger as well as sets the dog up to succeed and be rewarded, one of the cornerstones of positive training.

LIMA is a training method that pairs a very minimal aversive input with a higher presence of reward, with the goal being that the dog will no longer need the shock before they choose to turn and get their reward from the handler. Although the tools used in LIMA are the same as in other training philosophies such as dominance theory, the goal of LIMA is to have the dog progress so much that the trainer no longer needs to rely on the use of these tools, and that the dog will eventually choose the more favorable behavior without any outward stimulus from the handler. The use of aversive tools for the routine training of puppies or unreactive dogs is not LIMA. In an excerpt from the Certification Council for Professional Dog Trainers on the theory behind LIMA, “LIMA does not justify the use of punishment in lieu of other effective interventions and strategies. In the vast majority of cases, desired behavior change can be affected by focusing on the animal’s environment, physical well-being, and operant and classical interventions such as differential reinforcement of an alternative behavior, desensitization, and counter-conditioning” (“Least Intrusive”). In essence, the use of aversive tools is a small part of the LIMA method, and dogs are generally helped on a lower scale through the management of their environment and through the use of basic psychological tactics, such as classical and operant conditioning. Using tools strictly in an aversive manner without the use of conditioning and positive reinforcement is not LIMA, as the most aversive and intrusive method has been used first.

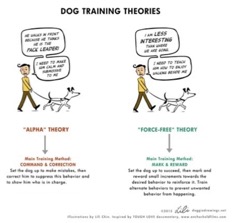

Another example of the difference in perspective between the philosophy behind LIMA and positive reinforcement methods versus aversive training mentalities is shown in an infographic illustrated and published by Lili Chin (Figure 1). Within, there is a clear example of the differences in perspective that these training methods use. For aversive training methods, sometimes called “alpha” or “dominance” theory, the idea is that the dog is disobeying because they believe that they are of a higher rank than the handler (Chin). The show Cesar 911 is one show in particular that has contributed to outdated training methods, like dominance theory, persisting in the dog training industry today. For positive reinforcement methods, also known as “force free” training techniques, the handler is told to acknowledge the idea that the dog is simply more interested in surrounding stimuli than the handler and that they should set their dog up to succeed rather than simply punish undesirable behaviors.

While the difference between these two mentalities is clear when explained in this way, it is not as clear to many, and some believe that it makes more sense that a dog is thinking itself to be more “dominant” than its handler. One reason for the perseverance of this belief is due to the appearance of dog training shows on platforms like cable TV and YouTube. The show Cesar 911 is one show in particular that has contributed to outdated training methods, like dominance theory, persisting in the dog training industry today. Several organizations have released statements against this show in particular, as well as statements speaking out against the methods used when following dominance theory (“Cesar Millan Response”, “Position Statement on Training Aids and Methods”, “Position Statement on the Use of Dominance Theory”).

One organization that has released such statements against these ideas is the American Veterinary Society of Animal Behavior (AVSAB). In the position statement, the Use of Dominance Theory in Behavior Modification, the AVSAB details several of the shortcomings of aversive training methods used in dominance training: “Evidence supports the use of reward based methods for all canine training… Negative reinforcement methods and aversive training tools have also been shown to increase levels of cortisol in dogs… Reward-based training methods have been shown to be more effective than aversive methods. Multiple survey studies have shown higher obedience in dogs trained with reward based methods…Aversive training has been shown to impair dogs’ ability to learn new tasks” (“Position Statement on Humane Dog Training” 1-2).

Cortisol is one of the biomarkers that researchers look for in order to evaluate stress levels in dogs. A study conducted by Ana Vieira de Castro et al. found that when dogs were trained using aversive methods, there were higher elevations of cortisol compared to the cortisol levels of dogs that had been trained using positive and rewards based methods (Vieira de Castro et al.). These high cortisol levels were also associated with more stress behaviors such as lip-licking, yawning, panting, etc. and spent more time tense during training in the aversive training group compared to the positive reinforcement group. The heightened presence of these hormones in the group using negative reinforcement suggests that the use of these methods increases the amount of stress that dogs feel during training, decreasing their enjoyment during training and their willingness to learn.

While the research documenting the consequences of using negative reinforcement methods versus positive reinforcement methods reaches back decades, some of the most recent studies examine a specific link between training methods used and the welfare of the dog (Kwan and Bain). In a study conducted by Nicola Rooney and Sarah Cowan, 53 dog owners were asked about their preferred training methods and asked to teach seven common tasks. This study found that owners using a higher proportion of punishment had dogs that were less likely to interact with a stranger and less playful. In this same study, it was found that dogs whose owners used aversive training methods were worse at performing novel tasks than dogs whose owners used positive training methods (Rooney and Cowan). The results of this study suggest that using techniques that incorporate the use of pain or force when teaching dogs a new skill is less effective than using positive reward methods, and can cause behavioral changes in the dogs that these negative methods are used on.

Due to the findings of such research studies, multiple organizations are calling for trainers to abandon aversive training tools and encouraging owners to seek out trainers that use positive training methods over all others. Using techniques that incorporate the use of pain or force when teaching dogs a new skill is less effective than using positive reward methods. One of these organizations is the Pet Professionals Guild, established in order to educate owners about the benefits of positive reinforcement methods. In an open letter written by representatives Angelica Steinker and Niki Tudge, various pitfalls of aversive training techniques are discussed, informing the reader of various problems with aversive training tools and explaining why these training methods should be retired. In an excerpt from this position statement, Dr. Sorya V. Juarbe-Diaz, DVM, discusses the fact that the use of aversive methods in behavior modification does not serve to teach dogs anything, it only stops the unwanted behavior: “Mistakes are inherent in any type of learning – if I continually frighten or hurt my students when they get something wrong, eventually they will be afraid to try anything new and will not want to learn from me any longer… sufficient scientific data in both humans and dogs [shows] that such methods are damaging and produce short term cessation of behaviors at the expense of durable learning and the desire to learn more in the future” (qtd. in Steinker and Tudge 2).

While some pet owners may not understand the difference between the idea of stopping an unwanted behavior and teaching an alternative behavior, it becomes clear with an all too real example of when a fearful dog punished for growling escalates their method of communicating discomfort from a low growl to a bite. Punishing the dog for growling, a verbal method to communicate fear to an apparent approaching threat, can lead to a dog forgoing this verbal warning and with no other behavioral option to fall back to, the dog decides that the only available action is to bite. This is an example of stopping a behavior with disastrous consequences. Instead, a more appropriate method is to teach the dog an alternative behavior to growling. Rather than punishing the dog for the behavior, the behavior is deterred by directing the dog’s attention to a different task. Some common tasks that fearful dogs are taught to fall back on include turning their attention to their handler for treats, sitting, lying down, or moving away from the threat. These are all options that the dog is taught to choose rather than growling, and all of these options would prevent a dog from believing that their only other option to growling is to bite.

The main reason that these harmful methods are still used is merely the fact that they are used on animals. Parents would never use any of these methods on children, but society perceives the use of these tools as acceptable on dogs. Juarbe-Diaz continues, “What most surprises me about the use of collars that choke… is that people think it is OK to use them in animals, whereas they would recoil in horror if teachers in schools were to use them in human pupils. We use force, pain and fear to train animals because we can get away with it… You can go with so-called tradition or you can follow the ever expanding body of evidence in canine cognition that supports teaching methods that encourage a calm, unafraid, and enthusiastic canine companion” (qtd. in Steinker and Tudge 2). As Dr. Juarbe-Diaz explains, just because something is traditional or something that one is familiar with, that does not mean that the method is automatically the best method available. As more and more studies are conducted on the effect that training has on the dog-handler bond, the more pet owners should elect to have their dogs undergo rewarding and positive training experiences in order to foster an attitude of confidence and a zest for learning.

As shown through the multiple studies conducted over the years on the effects that negative training methods have on learning in both humans and other animals, there is no evidence that aversive training methods are more effective than force free methods in any context. While aversive methods can be used in limited situations such as LIMA, there is absolutely no reason for dog owners to reach for a prong collar before a bag of treats. Animals are sentient, they deserve our compassion and respect. We assume the responsibility for their happiness and quality of life when we take them home, something that can be severely impacted by the training methods used. Thankfully, more and more dog trainers are becoming aware of the plethora of benefits that positive reinforcement methods have over aversive methods, allowing pet owners to become more educated and have more access to these scientifically proven training methods.

Works Cited

“Cesar Millan Response – AVSAB.” American Veterinary Society of Animal Behavior, 2016, https://avsab.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Cesar_Millan_Response-download.pdf.

Chin, Lili. “Doggie Drawings: Infographics.” Doggie Drawings, 2012, https://www.doggiedrawings.net/infographics.

Kwan, Jennifer Y, and Melissa J. Bain. “Owner Attachment and Problem Behaviors Related to Relinquishment and Training Techniques of Dogs.” Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 168-83, 2013, doi:10.1080/10888705.2013.768923.

“Least Intrusive, Minimally Aversive (LIMA) Effective Behavior Intervention Policy.” CCPDT, Certification Council for Professional Dog Trainers, 14 Sept. 2021, https://www.ccpdt.org/about-us/least-intrusive-minimally-aversive-lima-effective-behavior-intervention-policy/.

“Position Statement on Humane Dog Training – AVSAB.” AVSAB, American Veterinary Society of Animal Behavior, 2021, https://avsab.ftlbcdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/AVSAB-Humane-Dog-Training-Position-Statement-2021.pdf.

“Position Statement on Training Aids and Methods.” ASPCA, ASPCA, 2022, https://www.aspca.org/about-us/aspca-policy-and-position-statements/position-statement-training-aids-and-methods.

“Position Statement on the Use of Dominance Theory in Behavior Modification – AVSAB.” AVSAB, American Veterinary Society of Animal Behavior, 2008, https://avsab.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Dominance_Position_Statement-download.pdf.

Rooney, Nicola, and Sarah Cowan. “Training Methods and Owner-Dog Interactions: Links with Dog Behaviour and Learning Ability.” Applied Animal Behaviour Science, vol. 132, no. 3-4, pp. 169-77, July 2011, 10.1016/j.applanim.2011.03.007.

“The State of Animal Welfare Today.” Best Friends Animal Society – Save Them All, Best Friends Animal Society, 2021, https://bestfriends.org/no-kill-2025/animal-welfare-statistics.

Steinker, Angelica, and Niki Tudge. “Open Letter on Why Changes Are Needed.” The Pet Professional Guild – Open Letter on Why Changes Are Needed, Pet Professional Guild, 2012, https://petprofessionalguild.com/callforchangetrainingequipment.

Vieira de Castro, Ana, et al. “Carrots versus Sticks: The Relationship between Training Methods and Dog-Owner Attachment.” Applied Animal Behaviour Science, vol. 219, 2019, p. 104831, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2019.104831.

“What’s Wrong with the Prong?” SF SPCA, SFSPCA, 31 Dec. 2020, https://www.sfspca.org/behavior-training/prong/.