33 Artificial Intelligence: Misunderstood or Forgotten?

Nate McHenry

Writer Biography

Nate McHenry is halfway through his tenure at Utah State University, as he progresses toward a Physical Therapy Doctorate program. He currently lives with his wife and newborn daughter in Logan, UT, and enjoys the outdoor recreation in the area.

Writing Reflection

Researching artificial intelligence for this essay helped me to realize how much we depend on technological advances, and how taken for granted they are. Just the convenience it provides is amazing, and I wanted to take the opportunity to provide evidence in support of using AI.

This essay was composed in October 2022 and uses MLA documentation.

NOTE: McHenry researched and composed this essay before the November 2022 release of ChatGPT

MUSIC HAS EVOLVED with the rest of the world and has many different uses and meanings, a large portion of that is associated with emotional expression and connection. Used often in religious fervor, groups of people would gather to listen and perform to give thanks and plead before their gods and deities (Andrews). This creative expression is often used as a way to characterize what makes us human. Yet when composers, such as Iannis Xenakis, use artificial intelligence (AI) to compose emotionally moving pieces, is the human component lost? Rebecca Baker touches on this ethical question concerning AI in her essay “Computers vs Composers: A Modern War on Music” as she describes the use of technology in composing music. She argues for the use of computers and artificial intelligence in musical notation, that the emotional connection and expression found in music throughout history hasn’t been lost with computational composition, but that AI has allowed composers to broaden their creativity and innovation (Baker). Many artists today continue to use AI to provide quick and easy music, as well as virtual concerts used during the COVID-19 pandemic (Marr).

As Baker discusses the relationship between computers and composers, purposeful or not, she neglects to broach if it’s even ethical to use artificial intelligence. Much of the public’s opinion surrounding AI stems from a lack of knowledge and misperceptions about the technology. As these algorithms and learning software started to gain rampant use and publicity in the early 2000s, a research article was published to help answer some of the many questions surrounding this technology. Appropriately titled “What Is Artificial Intelligence?”, John McCarthy provides a simple question-and-answer-formatted paper to put to ease several worries from the public. Is artificial intelligence really how it’s portrayed in movies and pop culture, evolving quickly and dangerously, such as the AI supervillain Ultron in Avengers: Age of Ultron? No, not really (McCarthy). This article provides a great baseline to compare how it has grown the past few decades as other publications are released through the years, especially with 2020 research by William Rapaport, who even gives artificial intelligence a more accurate name to further quench the surrounding anxieties. He determines that computational cognition is a more respectable and understanding title which will be explored later (Rapaport). As AI has evolved and more research has been done revolving around its use, artificial intelligence remains a series of closed-ended algorithms that provide ease and efficiency in accomplishing tasks, thus giving it a positive ethical value.

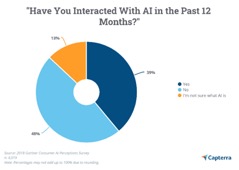

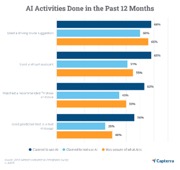

The largest argument against the use of artificial intelligence is that the public is generally scared of using it, but this fear stems from the unknown. Brian Westfall presents statistics taken from Gartner research about how much a population understands about AI (Figures 1 and 2). The trends show that when asked at the time of the study, 48% of people had not interacted with AI in the past 12 months with another 13% not sure what AI even is (Westfall). Unfortunately, we do not know how much of the statistics overlapped and in which direction, but the percentage of people who claimed to have not used AI in these four activities is surprising. What these individuals do not understand is that “intelligence is the computational part of the ability to achieve goals in the world” (McCarthy). In other words, the intelligence part of AI allows someone to get from point A to point B using a smartphone or GPS; search for information across databases; control a smart home through a virtual assistant; find a new movie or television show to watch based on previous streams; and even use predictive text or grammar correcting services while texting or writing essays. The percentage of population who miscomprehend the technology despite using it daily is astounding. Meanwhile, the developers of certain AI use an unwritten rule that these services don’t need to be foolproof, they just need to be “good enough” (Rapaport 53). This policy allows for AI to be seamlessly inducted into daily living to improve these seemingly common tasks.

Rapaport provides analysis for several different definitions, but ultimately his own definition is simplest. He explains that “artificial” and “intelligence” do not properly convey what is really being accomplished as artificial is associated with fake, and just as neurons firing in a human’s nervous system is a real thing, so are the bits of information being passed within a computer system. In synthesizing the work of Wang, Rapaport states “[h]e seems to think that if AI is computational, then there must be a single algorithm that does it all (or that is ‘intelligent’). He agrees that this is not possible; but whoever said that it was?” (Rapaport 53). Consequently, Rapaport prefers the term “computational cognition,” though it can still be abbreviated to AI (Rapaport 54).

Despite the population’s lack of knowledge about artificial intelligence, a great percentage of corporations and businesses are adding AI to their repertoire. So why are businesses turning to computational cognition? Won’t implementing this technology cause so many individuals to become unemployed? Companies are trying to maximize profits, and they do this with AI in two ways: augmentation and automation. Both are used to create efficiency. Automation is “the removal of humans from an activity,” taking out human error from specific tasks, while augmentation is “the empowering of humans in an activity” (Bergdahl). While machines and software may be replacing workers, most of these jobs are cases where the individual being affected does not have comparative advantage, or the ability to do said task more effectively than another task. Specialization is instead being increased because now someone must maintain the system, and they also need to teach other people how to use and maintain the learning machines.

As stated before, companies are trying to maximize profits and another way to do so uses a method called the productivity theory. The productivity theory, in simple terms is the ability to increase production in multiple ways and make the laborer more valuable. “[A]utomation raises the demand for labor in nonautomated tasks” (Acemoglu and Restrepo 6). As a task increases in complexity, the value of an employee increases with it. Augmentation allows for this process to be sped up and allows the user more creativity in their field. As artificial intelligence is continually implemented in the workplace, the value of the employee increases for responsibilities that cannot be accomplished by technology alone.

While these ideals could be explored further and theories and data trends used to predict future use and capabilities of artificial intelligence, the evidence provided is sufficient to satisfy the claim that AI is a great tool. Though the fear of the unknown hinders the progress of AI slightly, the observations made from its use show that this and relative technology trend positively on an ethics scale. The implementation of artificial intelligence in the workplace allows for an increase of jobs, and of job productivity. All thanks to software that has the ability to compute cognitive tasks.

Works Cited

Acemoglu, Daron, and Pascual Restrepo. “Artificial Intelligence, Automation and Work.” NBER Working Paper Series, National Bureau of Economic Research, Jan. 2018, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w24196/w24196.pdf.

Andrews, Evan. “What Is the Oldest Known Piece of Music?” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 18 Dec. 2015, https://www.history.com/news/what-is-the-oldest-known-piece-of-music#:~:text=The%20history%20of%20music%20is,been%20preserved%20in%20oral%20traditions.

Baker, Rebecca. “Computers vs. Composers: A Modern War on Music.” Voices of USU: An Anthology of Student Writing, vol. 15, 2022, pp. 11–24.

Bergdahl, Jacob. “4 Business Strategies for Implementing Artificial Intelligence.” Medium, Towards Data Science, 23 Feb. 2021, https://towardsdatascience.com/4-business-strategies-for-implementing-artificial-intelligence-24deff39158c.

Hamman, Michael. “On Technology and Art: Xenakis at Work.” Journal of New Music Research, vol. 33, no. 2, 2004, pp. 115–23. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1080/0929821042000310595.

Marr, Bernard. “How Artificial Intelligence (AI) Is Helping Musicians Unlock Their Creativity.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 14 May 2021, https://www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2021/05/14/how-artificial-intelligence-ai-is-helping-musicians-unlock-their-creativity/?sh=5d90c1907004.

McCarthy, John. “What Is Artificial Intelligence?” Professor John McCarthy: Father of AI, Stanford University, 2007, http://jmc.stanford.edu/artificial-intelligence/what-is-ai/index.html.

Rapaport, William J. “What Is Artificial Intelligence?” Journal of Artificial General Intelligence, vol. 11, no. 2, 2020, pp. 52-56, DOI: 10.2478/jagi-2020-0003.

Westfall, Brian. “How to Prepare Employees for AI in the Workplace.” Capterra, 26 Feb. 2020, https://blog.capterra.com/how-to-prepare-employees-for-ai-in-the-workplace/.

elf.