32 Social Media and National Parks: Our Duty to Travel Responsibly

Jessica John

This essay was composed in December 2021 and uses MLA documentation.

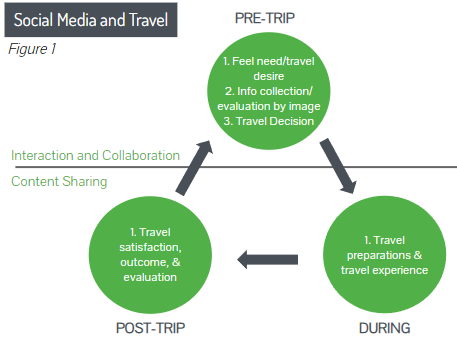

IN 1901, JOHN MUIR, the father of national parks in the U.S., said that “thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wilderness is a necessity; and that mountain parks and reservations are useful not only as fountains of timber and irrigating rivers, but as fountains of life” (Muir). Despite being said well over a century ago, Muir’s statement holds more truth than ever today. National Parks have been a staple of American outdoor recreation since the beginning of their introduction. Nonetheless, technological advances, the slew of Covid-19 anxieties, and our everyday fast-paced society have driven people to nature in record numbers. Though nature has been a constant, it hasn’t been unaffected by the vast changes our society has undergone, including the exponentially increasing influence of social media. In 2015, Instagram had 370 million annual users, and Facebook had 1.49 billion annual users (Facebook, and Statista). This data also shows that in the five short years between 2015 and 2020, those numbers skyrocketed. Instagram experienced an increase of 538.2 million people, giving them 908.2 million annual users. Similarly, Facebook experienced an increase of 1.3 billion people, landing them at 2.79 billion annual users (Facebook, and Statista). As social media has grown and strengthened its presence in our culture, it has become a key factor in multiple facets of decision-making. A Gallup Poll in 2014 found that 62% of Americans felt that social media had no influence on their purchases at all, but that number has been completely overturned in recent years, with 73% of teens reporting that social media is the best way to advertise products and promotions to them (Barysevich). In addition to everyday consumer decisions, social media has completely transformed the way people decide on and plan travel. Whether it is finding the perfect destination or posting our own vacation pictures, social media has made it easier than ever to find the best trip possible. In 2017, published communications researcher Dr. Rizki Briandana developed a multi-phase cycle that details how social media is involved in our travel decisions. Focused particularly on platforms based on photo sharing such as Instagram and Facebook, the cycle involves interaction and collaboration in the first phase and content sharing in the second phase (Figure 1).

In the first phase, the emphasis on information collection and evaluation by image highlights social media’s influence on how people decide where they want to travel. The speed at which information and photos can spread through social media has increased exposure to previously isolated destinations, including those of National Parks, at an unprecedented rate, altering many historical travel patterns. As it is currently being utilized, increased social media usage is doing more harm than good when it comes to National Parks and other protected lands.

Like most things in the age of technology, National Parks have been experiencing extensive changes. Overcrowding has moved to the forefront of the slew of problems facing our National Parks. Multiple parks, including Yellowstone, Zion, and the Grand Tetons have set monthly visitation records this year. Zion, for example, blew their previous monthly record of 595,000 visitors in June of 2019 out of the water in June of 2021 with 676,000 visitors that month (Associated Press). The Parks system is not equipped to handle high influxes of visitors. The infrastructure is out of date, they are often understaffed, and the parks simply lack the space. The overcrowding has prompted concerns over the safety of visitors, staff, and even wildlife. During the summer of 2021, “Arches national park had to close its gate more than 120 times this summer alone when parking lots filled up, creating a safety hazard for emergency vehicles,” making high volume days that much more dangerous (Gammon). Increased visitation may come from a variety of changes in our present-day culture, but a prominent one is social media. As it is currently being utilized, increased social media usage is doing more harm than good when it comes to its effects on National Parks and other protected lands.

To begin with, social media travel inspiration accounts play a significant role in increasing visitation to National Parks and other protected lands. Back in 2014, my dad, grandmother, brother, and I decided to hike into the Grand Canyon to camp in Havasupai. Our reservation was booked during monsoon season, and at the time, you could abandon your reservation for a full refund or simply reschedule for a later date. Because of this, when the forecast showed rain, the entire hike and much of the falls themselves were free of other tourists. However, Havasupai quickly lost its status as a hidden gem as travel Instagram accounts gained traction. With its picturesque teal waters, Havasupai appeared front and center on countless travel inspiration Instagram accounts and bucket list travel blogs, including @havasupaifalls, a travel inspiration account with over 41,000 followers. In turn with this increase in exposure and photo-sharing, visitation to Havasupai started skyrocketing. Reservations are no longer refundable, and the waitlists have seen dramatic increases. This is not an isolated phenomenon. Stunning, almost too-good-to-be-true photos of travel inspiration from locations all around the United States and even the world go viral across Instagram regularly. Kanarraville Falls, just south of Zion, is considered a victim of social media’s influence. Charlotte Simmonds with the Guardian stated that the falls were “once a hidden gem but now featured in countless Instagram posts.” She also noted the way the stream banks are experiencing extreme erosion and are consistently littered with trash due to increases in tourists and hikers who saw the Kanarraville Falls on social media. These accounts serve as highly effective advertisements to the billions of social media users searching for travel destinations. Some argue that travel-centered social media is not a negative factor but rather a positive information center that allows more people to experience America’s beautiful places. While this is certainly true, this aspect of social media’s impact is misused as well as underutilized. When encouraging travel to these places based solely on aesthetics, uninformed tourism increases. The lands in National Parks are protected for a reason, meaning that travel to these areas often require more research and information than other vacations. Because this research tends to be lacking when travel is decided upon based solely on social media, it has numerous side effects that are damaging to the protected lands in National Parks.

Social media’s influence on the increasing tourism to National Parks has generated and escalated the sustainability issues many of them are facing. The dramatic influx in tourism that led to overcrowding has caused substantial increases in pollution in National Parks. A study conducted by researchers at Iowa State found that ozone levels in 33 of the largest National Parks in the United States “were statistically indistinguishable from those of the 20 largest U.S. metropolitan areas” (Keiser et al.). The packed parking lots and backed-up roads in National Parks are not simply a hassle for visitors now but are worsening the air quality in the lands we are trying to preserve. While climate change is a global issue, research shows that National Parks “bear the disproportionate brunt of global warming” (Simmonds, et al). The Park Service is not equipped to keep up with the environmental challenges. The infrastructure was last fully updated in the 1960s, leaving the parks woefully unprepared for the increased crowds and environmental challenges. For example, Havasupai is particularly susceptible to flash floods. These floods are highly detrimental and leave the waterfalls and river in a very fragile and unstable condition, so as influxes of hikers and tourists increase foot traffic and further degrade the fragile soil. In addition to the worsening environmental impacts, the chief spokesperson for the National Park Service, Jenny Anzelmo-Sarles, has noted that the more visitors the parks see, the more graffiti, litter, and careless behavior they see (Gammon). Not only does this cause problems for the preservation of the parks themselves, but it also poses issues for the towns that surround them. Water pollution and other contaminants from influxes of tourists have affected the people of surrounding towns. To this, there is an argument that the economic benefits of increasing tourism in National Parks outweigh the ecological harm, especially considering the fact that much of the revenue generated goes back into the National Parks System. However, social media’s influence has caused the increase in visitation to rise so much that even with the extra revenue, the maintenance crews cannot keep up with the rate of pollution and overcrowding. Additionally, the economic benefits do not have to come at the cost of conservation, which was a large goal of establishing National Parks. Revenue can be maintained and even increased through reservation systems, standard entry fees, and private philanthropy. The prominent pollution from overcrowding in the parks proves just how powerful social media is, especially when it is being improperly utilized.

Social media-driven overcrowding is not only dangerous to the preservation of the National Parks themselves but also for the tourists themselves. Uneducated tourists and higher crowds have led to higher numbers of preventable accidents, including dehydration, fatal falls, dangerous animal encounters, and simply careless behavior. A study on accidents and accountability in National Parks by environmental communications researcher Dr. Rickard found that each year, approximately 6,000 visitors of National Parks suffer serious injuries or fatalities. Additionally, the National Park service responds to over 14,000 emergency medical events and 4,000 search and rescues nationwide (Rickard). Because social media platforms such as Instagram and Facebook focus largely on sharing photos, many of the tourists who chose their destinations based on aesthetic photos are largely uneducated about the areas they are visiting. Dr. Rickard’s study found that there tends to be a “perception of invulnerability” and an “exaggerated sense of control” in tourists that can increase accidents. When most of our information is gathered through social media, and there are such dramatic lines and waits, it is easy to forget that National Parks are still wild lands and not a natural Disneyland. This misconception about the nature of National Parks deflects the blame from our own carelessness as tourists and unfairly places it on the National Park Service and park rangers themselves. During an interview I conducted with the hosts of the popular “National Park After Dark” podcast, Cassie Yahnian and Danielle LaRock, they discussed how the public reacts to accidents in National Parks. LaRock and Yahnian noted that there is a strong perception of National Parks as a controlled environment when in reality they are some of the only “true wild places” left. LaRock cited social media as a huge driving factor for this false sense of security, recalling a story of tourists attempting to sue the National Park Service after a tragic bear attack, with the tourists’ family arguing that dangerous animals should be fenced in. However, the victims were uneducated and disregarded signs posting advice on proper camping locations and practices in the park.

While accidents and fatalities in National Parks are not new, they have been increasing as the parks become more crowded. In Yosemite alone, there has been a “90% increase in vehicle accidents, a 60% bump in calls for ambulance services and a 130% rise in searches and rescues,” putting a severe strain on park staff and resources (Simmonds). In addition to outdated infrastructure and clogged roads, the overcrowding of National Park Service staff and park rangers is severely overwhelmed by the influx of tourists. Park rangers are severely overwhelmed, trying to manage the park logistics, rowdy tourists, and the influx of accidents. Due to budget restrictions, staffing has stayed the same, even in spite of the swelling visitation rates. Very few park rangers are fully specified in one area of park management; most rangers are expected to be equipped to handle parking, traffic control, rescues, preservation and conservation, and more, meaning that they are stretched thin. As tourists, it is our responsibility to educate ourselves on these areas in order to preserve them in the pristine state they were meant to be, rather than expect to come into a highly controlled, regulated environment. That is simply not the nature of our National Parks.

Furthermore, in addition to increasing exposure to a lot of our National Parks, social media creates a drive to find the “perfect picture.” Many of the photos on social media of these scenic destinations are unrealistic, whether that includes editing, photoshop, or rare circumstances, but their beauty has caused many tourists to seek out these photos themselves. The search for these photos has driven tourists to the scenic National Parks in droves, which contributes to both overcrowding and an increase in preventable accidents. In 2018, Meenakshi Moorthy and Vishnu Viswanath fell to their deaths in Yosemite National Park while taking a selfie on a cliffside 1,000 feet above the floor of the valley (McCormick, Safi). Maschelle Zia, manager of Horseshoe Bend, stated that “social media is the number one driver” and that “people don’t come here for solitude–they are looking for the iconic photo” (Simmonds). The hosts of “National Park After Dark” described the changes they’ve seen over the years as regular visitors of the parks across the country. When LaRock first began visiting National Parks, any pictures there were taken on digital cameras. The crowds were significantly smaller than the ones we see today, stating that the appearance of cell phones seemed to go hand in hand with the drastic crowd increases (John). Geotagging, or using GPS to pin the exact location photos on social media were taken, has increased the problematic search for the perfect picture by allowing others to track the spot and flooding it with phone-toting tourists. However, geotagged social media posts have also benefited the parks in some ways. There is an argument for the positive benefits of social media through its use as a form of citizen science. Social media posts have allowed environmental scientists to analyze greenness in seasonal cycles of vegetation across National Parks with a “95% confidence level” in areas that lack significant high-quality monitoring systems (Silva). It is inarguable that social media has proved to be a powerful data collection tool and a vessel for citizen science. It has provided data on tourist behaviors, as well as the flora and fauna of the parks. However, increased tourism increased preventable erosion, encroaching, and trampling of said flora and fauna. Its data can certainly be used for study and conservation, but the benefits don’t currently outweigh the environmental damages National Parks are experiencing due to increased, social media-motivated tourism.

Our National Parks are suffering. Our love for them is causing their degradation. What can be done? There are numerous proposed solutions, though not always popular. The most effective solution we have available at this time is placing tighter capacities on the number of visitors allowed into each park at a time. The capacities should be specifically tailored to each park based on size and environmental stability, as well as the busy and slow seasons. During slow seasons, National Parks should tighten the capacity limits to allow for natural regeneration, as well as for man-powered restoration and conservation efforts, which would allow them to be better prepared for the busy seasons. Furthermore, we have already established that social media has a powerful influence on tourists visiting these protected lands. This capacity for education and influence is severely underutilized, and it can be used to increase knowledge of safe, responsible, and sustainable practices in National Parks. Many of the National Parks Instagram accounts already include safety and travel tips in their captions, and this can be easily applied to travel inspiration accounts and blogs. As travelers and tourists ourselves, we can also spread awareness about safety tips or places to properly educate ourselves in order to create safer trips both for ourselves and our environment. Danielle LaRock and Cassie Yahnian focus on adding safety tips and advice about proper practices into their podcast after their story, hoping to educate their audience and establish relatability. In the wise words of Cassie Yahnian: “the first step is getting people to care, and when they care, good things come into play.” We have the power to influence the fate of protected lands in the United States. The immense power of social media is quite literally at our fingertips, and we have a responsibility to use its influence for good. In a world faced with the horrific effects of climate change, protecting these wild places is more important than ever. So despite the fact that as it is currently being utilized, increased social media usage is doing more harm than good when it comes to National Parks, it has the potential to create lasting and positive environmental change.

Works Cited

Associated Press. “Zion National Park Sets Another Visitation Record | Utah …” Zion National Park Sets Another Visitation Record, 19 July 2021, https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/utah/articles/2021-07-19/zion-national-p ark-sets-another-visitation-record.

Barysevich, Aleh. “How Social Media Influence 71% Consumer Buying Decisions.” Search Engine Watch, 20 Nov. 2020, https://www.searchenginewatch.com/2020/11/20/how-social-media-influence-71-co nsumer-buying-decisions/.

Briandana, Rizki, and Nindyta Dwityas. “Social Media in Travel Decision Making Process.” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, July 2017, https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Rizki-Briandana/publication/322749479_Soci al_Media_in_Travel_Decision_Making_Process/links/5a6d1877458515d40757109 e/Social-Media-in-Travel-Decision-Making-Process.pdf.

Facebook, and Statista. “Facebook Mau Worldwide 2021.” Statista, Facebook, 1 Nov. 2021, https://www.statista.com/statistics/264810/number-of-monthly-active-facebook-users-worldwide/.

Gammon, Katharine. “National Parks Are Overcrowded. Some Think ‘Selfie Stations’ Will Help.” SEJ – Society of Environmental Journalists, 1 Sept. 2021, https://www.sej.org/headlines/national-parks-are-overcrowded-some-think-selfie-stations-will-help.

John, Jessica, et al. “Social Media and Our National Parks with Hosts of National Park After Dark.” 12 Nov. 2021.

Keiser, David, et al. “Study: Air Pollution and National Park Visitation.” Study: Air Pollution and National Park Visitation | Department of Economics, 19 July 2018, https://www.econ.iastate.edu/study-air-pollution-and-national-park-visitation.

McCormick, Erin, and Michael Safi. “‘Is Our Life Just Worth a Photo?’: The Tragic Death of a Couple in Yosemite.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 3 Nov. 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/nov/02/yosemite-couple-death-self ie-photography-travel-blog-taft-point.

Muir, John. “Our Forests and National Parks.” Our Forests and National Parks, by John Muir, 1901, https://college.cengage.com/history/ayers_primary_sources/forestsnational_parks_ muir_1901.htm.

Rickard, Laura N., and Sara B. Newman. “Accidents and Accountability: Perceptions of Unintentional Injury in Three National Parks.” Leisure Sciences, vol. 36, no. 1, Jan. 2014, pp. 88–106. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1080/01490400.2014.860795.

Silva, Sam J., et al. “Observing Vegetation Phenology through Social Media.” PLoS ONE, vol. 13, no. 5, May 2018, pp. 1–14. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0197325.

Simmonds, Charlotte, et al. “Crisis in Our National Parks: How Tourists Are Loving Nature to Death.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 20 Nov. 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/nov/20/national-parks-america-ov ercrowding-crisis-tourism-visitation-solutions.

Swift, Art. “Americans Say Social Media Have Little Sway on Purchases.” Gallup.com, Gallup, 23 June 2014, https://news.gallup.com/poll/171785/americans-say-social-media-little-effect-buyin g-decisions.aspx.