23 Social Media and Politics: Polarizing America

Sarah Young

About the Author

Sarah Young was born and raised in Boise, Idaho until she moved to Logan, Utah to attend Utah State University when she was 18 years old. She is currently a sophomore studying English and plans to attend law school upon completion of her Bachelor’s degree. Sarah currently works at the library on campus and for fun, she plays on the Utah State women’s rugby team, as well as enjoys going on walks.

In Her Words: The Author on Her Writing

I chose to write about this topic because I’m sad and tired seeing how my peers interact with each other—people are mean. As I conducted my research, the Pew Research Center provided me with the most compelling and accessible information, as well as a multitude of articles pulled from the USU Library databases. I used a synthesis matrix to combine my research and from there, the essay sort of put itself together.

This essay was composed in April 2022 and uses MLA documentation.

I WAS HAVING A CONVERSATION WITH MY YOUNGER SISTER a month or two ago about politics. It was a conversation that contained eerily similar complaints to ones that I have seen and heard many times in the comment sections of TikToks, in Instagram captions, and posted to countless Facebook stories. This conversation started as most conversations do when it comes to politics, with feelings of anger. My sister was telling me about how an old family friend—a good, kind boy she’d spent her childhood with—was a Republican. Now this may seem like a small inconsequential fact about this boy, but to my 16-year-old sister, finding out he was a Republican (a party she couldn’t accurately describe if her life depended on it) was like finding out he was a monster. I wish I was exaggerating, but she was genuinely crushed by the news. I asked her why she cared and she responded with—and this is a direct quote—“Cuz Republicans, conservatives, whatever, are the scum of the earth.” I was astonished. We both knew this boy our entire lives and she had loved him wholeheartedly up until that day. Yet all it took for her to change her mind about his character, values, and even place in society was his political affiliation. I bring up this story because it encapsulates a growing fear I have. My fear is that it has become all too easy and all too common to hate people who have differing beliefs than our own. This fear didn’t start with that conversation with my sister, though. As I said prior, comments like hers are ones I have read all over social media about any and everything political. And so more accurately, my fear is that this ease of hate, accompanied by a myriad of negative mindsets and actions, has been emphasized, encouraged, and fortified by the use of social media.

Social media was created with a vision of growing democracy, a new and improved network of communication with friends, family, work, and the world in general; it was meant to be a resource and a tool for progress and positive change. Many scholars argue that the presence of social media in the world has done a lot of good. And they’re right; social media has exponentially increased the amount of easily available information, it’s a hub for creating and developing relationships, and it’s a great form of cheap, simple entertainment. The purpose of this essay is not to argue that social media is inherently bad. The concern and problem needing to be discussed is rooted in the fact that social media has also become one of the dominant resources for sharing and receiving news in our society. In fact, according to a survey conducted in the summer of 2021 by the Pew Research Center, about 48%, or nearly half, of all adults living in the U.S. say they get their news off of social media at least “often” (Walker). It’s an undeniable fact that news in the U.S. is widely received and shared on a variety of social media platforms because social media has become less of an option for communication and more of a monopoly over it.

Social media use for news is not the only statistic on the rise in recent years. The United States seems to have divided and dug itself into trenches of harsh, unrelenting polarization across political parties. Specifically, and most notably between the Democratic and Republican parties, as well as politically conservative versus liberal citizens. It’s gotten to the point that popular news media stations like Fox News and CNN cover and write more about anti-opposing party propaganda than the actual news; there is almost nowhere unbiased to turn for facts, stories, and information that isn’t laced with traces of partisan hatred. This lack of credibility in the typical news media is a huge cause for concern, especially when considering the effects of it. People are constantly hearing subtle and obvious hate speech about the other half of the entire country and it has pitted U.S. citizens against each other on a new and surprising level.

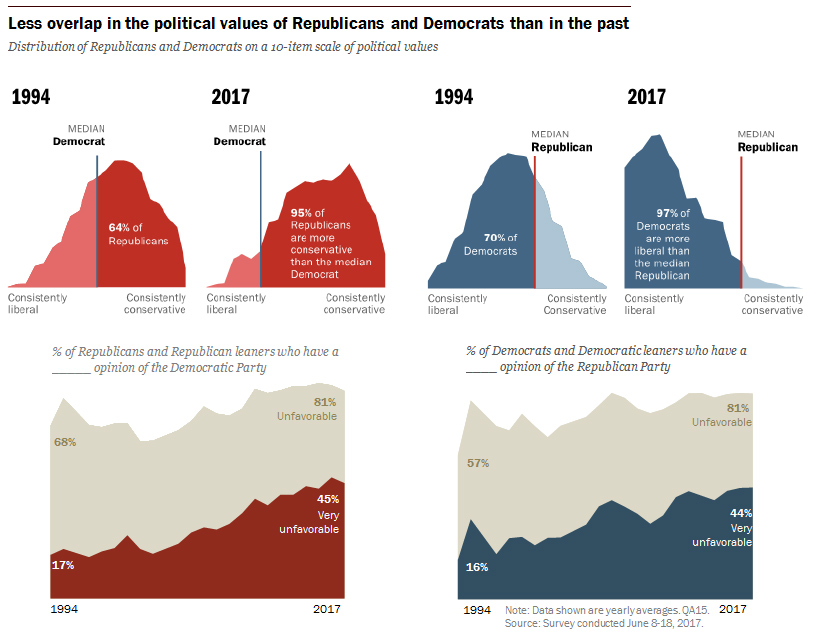

The image above shows a comparison of overlap in political values between Democrats and Republicans as well as the percentages of opinion regarding the opposing party (refer to Figure 1). The data shows significantly less overlap between political values with numbers jumping from 64% of Republicans showing consistently conservative beliefs in 1994 to 95% in 2017. The same was observed for Democrats voting liberally. In 1994, 70% showed liberal values and the percent only increased in the following years, jumping all the way up to 97% in 2017. Even more concerning than this loss of overlap and mutual understanding is the data showing that in 2017, almost half of all Democrats and Republicans reported having a “very unfavorable” opinion of the opposing party and over 80% reported an “unfavorable” one. The animosity felt between political parties in this country is unquestionable. However, it does beg the question of causality and possible influences. These questions are what prompted my research into how social media has impacted political polarization in the United States. Throughout my research, I found many sources discussing a multitude of opinions and research done; however, it proved difficult acquiring empirical evidence because polarization is based on human emotion and that is always tricky to capture. Regardless of this difficulty, I discovered four main impacts that were consistent throughout my resources and findings: Social media has created an echo chamber effect on its users, aided in the arousal of problematic viewpoints, fake news, and an overall increase in the dehumanization of peers.

Social media is built according to such an algorithm that users are able to self-select the information they want to see. This ability is one of the many favorite aspects of social media; it can be an entirely personalized experience, making it an excellent source for entertainment. However, this personalized experience contributes to polarization in a powerful way. In “How Social Media Shapes Polarization,” an essay mainly about how social media has negatively impacted society and individual cognition and the nuances surrounding the use and effects of algorithms on social media platforms, the authors explain,

. . . different platforms may facilitate different types of polarization . . . Some platforms’ algorithms seem to amplify content that affirms one’s social identity and pre-existing beliefs. For instance, Facebook’s news feed seems to increasingly align content with cues about users’ political ideology. (Van)

The authors were discussing in this paragraph how individual algorithms are slightly different in how they affect polarization, but they all do in some way. One key way in which algorithms work to polarize people is by aiding in the creation of echo chambers. The term echo chamber refers to the effect of self-selecting the information one sees on their social media feed. These effects, as shown by a study done in 2010 by the Department of Psychology at the New School for Social Research in New York, include the creation of tight-knit groups who share congruent beliefs, the fostering of polarized values in such groups, intensified reactions/responses to moral disagreeances, and an overall reduction in openness and willingness to hear divergent opinions (Carpenter). The insulation from opposing points of view is a recipe for polarization and stringent isolation of beliefs and values because there is no room left for the consideration of alternative ideas.

Beliefs and values are entirely individualistic and so there is, to some degree, room for the creation of positive ingroups and a sense of duty and loyalty within such groups. However, it is impossible to fully grasp an issue or idea with only personal beliefs and research as one’s evidence. It is also all too easy to get caught up in the storm of fake news present on social media and have said beliefs be misconstrued and distorted in such a way that progress and learning become hindered even further. Fake news is any false or misleading information that is created to be shared with a purpose in mind. The purpose is typically to gain money or to wound/uplift someone’s reputation. It’s been said that “[p]artisan polarization is the primary psychological motivation behind political fake news sharing on Twitter” (Osmundsen). Polarization and fake news media are inevitably linked. In fact, in 2021, social media was recognized as “the least trustworthy news source worldwide,” yet well over half of all Facebook and Twitter users reported using those respective platforms “regularly” as their source for news (Djordjevic).

The article, “Does the Internet Make the World Worse? Depression, Aggression, and Polarization in the Social Media Age” discusses the overall impact social media has had on users and consumers since its inception in the early 2000s. The authors explore questions surrounding how social media has increased suicide rates and depression in multiple countries, how it has made users more aggressive towards each other, and most importantly for this discussion, how social media has contributed to political polarization. The authors presented many interesting points and claims regarding self-reinforcement (“echo chamber” effects experienced by users), data surrounding extreme viewpoints and their amount of interaction and followers, as well as the incentives surrounding the spread of fake news and propaganda. The author, Christopher Ferguson, specifically noted documented incentives, by means of campaign donations, for politicians to spread more extreme views, propaganda, and false information (Ferguson). The impact of not only the internet being filled with false facts, but of political machines promoting this spread of fake news is detrimental to society to say the very least. In fact, according to Berta García-Orosa, the author of “Disinformation, Social Media, Bots, and Astroturfing: The Fourth Wave of Digital Democracy,” there is a huge “cause for concern about the manipulation of citizens, especially around elections and referendums, through the creation of artificial public opinion that could provoke chaos and conflict in politics” (García-Orosa). The normality of fake news on social media paired with abuse of this normality from politicians has a direct, intentional, and divisive effect on polarization in the U.S.

In the same vein, problematic viewpoints, specifically data-deficient and extreme ones, spread widely and quickly on social media. Underqualified people, as well as those harboring extreme views, can post whatever and whenever they want with little to no repercussions. These beliefs are shared and then none-the-wiser users are subjected to it, and oftentimes people take what they see at face value and adopt the same or similar beliefs. In fact, data suggests that politicians who display the most extreme views on social media, also have the highest number of followers (Ferguson). This shows that extreme views have an extremely high likelihood of being shared across media platforms and are even incentivized in a way by the algorithms’ promotion of content that has a high number of views, or content creators who have a high number of viewers. According to a study done on nearly three million different social media posts, the posts that were about a political opposition were more likely to be shared than those about a political friend—especially if said post reflected “animosity” toward that opposition (Van). Viewers who have most likely found themselves in an echo chamber of their own. According to the authors of “Political Polarization and Moral Outrage on Social Media,”

. . . the prevalence of one sided arguments and the marginalization of deviant views may facilitate the expression of increasingly extreme viewpoints. Perceptions of community consensus may foster the emergence of tight knit group identities and embolden extreme members to speak up. (Yarchi 5)

The authors are essentially saying here that users isolated by echo chambers have a high tendency toward joining insulated groups who are oftentimes prone to the extremes.

Finally, when considering all of the prior mentioned impacts on polarization, there is one final impact that they all contribute to: the dehumanization of one’s peers. Specifically referring to online incivility and an overall lack of empathy shown, as well as received. Research shows that as interactions between politically opposed groups become rare, there is a congruent effect of eroding respect and empathy for members of those groups or any other outsiders (Yarchi 5). Unfortunately, this means that there is a severe loss in effective, bipartisan communication between U.S. citizens, as well as between politicians. Not only is there a loss of communication, there is the loss of empathy and respect. People are downright inhumane to others online and the reason behind why this occurs is put simply and accurately here: “. . . expressing outrage is easy online because the target of the outrage need not be present, the potential for retaliation is minimal, and distant targets inspire less empathic concern” (Carpenter).

Polarization in the U.S. is at an all-time high and has only been on the rise since the creation and popular adoption of social media. Social media acts as an unreliable, intoxicating, and destructive method of communication. The possibilities for psychological damage and distortion are nearly endless and so it really is no wonder this country has become so divided. Of course, social media has its redeeming qualities when it comes to entertainment, but it also has wreaked havoc on public opinion, intelligence, and humanity, which cannot and should not be ignored. Because of the way social media is built and functions, it is the individual responsibility of all users to take the information and stories they hear on these platforms with a grain of salt; to not take what they see at face value and to make active attempts at understanding the views of others and accepting them as humans capable and deserving of their own beliefs. Moral of the story: Don’t be like my sister.

Works Cited

Carpenter, Jordan, et al. “Political Polarization and Moral Outrage on Social Media.” Connecticut Law Review, vol. 52, no. 3, Feb. 2021, pp. 1107–20. EBSCOhost, https://dist.lib.usu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=asn&AN=149895908&site=ehost-live

Djordjevic, Milos. “27 Alarming Fake News Statistics [the 2021 Edition].” Letter.ly, 1 Apr. 2021, https://letter.ly/fake-news-statistics/.

Ferguson, Christopher J. “Does the Internet Make the World Worse? Depression, Aggression and Polarization in the Social Media Age.” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, vol. 41, no. 4, Dec. 2021, pp. 116–35. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.1177/02704676211064567.

García-Orosa, Berta. “Disinformation, Social Media, Bots, and Astroturfing: The Fourth Wave of Digital Democracy.” El Profesional de La Información, vol. 30, no. 6, Nov. 2021, pp. 1–9. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2021.nov.03.

Osmundsen, Mathias, et al. “Partisan Polarization Is the Primary Psychological Motivation behind Political Fake News Sharing on Twitter.” American Political Science Review, vol. 115, no. 3, Aug. 2021, pp. 999–1015. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000290.

Pew Research Center. “Less Overlap in the Political Values of Republicans and Democrats than in the Past.” Visual Capitalist, Visual Capitalist, Oct. 2017, https://www.visualcapitalist.com/charts-americas-political-divide-1994-2017/.

Van Bavel, Jay J., et al. “How Social Media Shapes Polarization.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences, vol. 25, no. 11, Nov. 2021, pp. 913–16. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.07.013.

Walker, Mason, and Katerina Eva Matsa. “News Consumption across Social Media in 2021.” Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project, Pew Research Center, 20 Sept. 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2021/09/20/news-consumption-across-social-media-in-2021/.

Yarchi, Moran, et al. “Political Polarization on the Digital Sphere: A Cross-Platform, Over-Time Analysis of Interactional, Positional, and Affective Polarization on Social Media.” Political Communication, vol. 38, no. 1/2, Jan. 2021, pp. 98–139. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1785067.