8 Growing the Leaders of Tomorrow Through Agricultural Education

Jeremy Case

About the Author

Jeremy Case grew up in Twin Falls, Idaho, where he participated in 4-H and FFA for most of his high school experience. He enjoys riding in equestrian sports, quilting, and photography. At USU, he’s a member of Sigma Phi Epsilon, Collegiate 4-H, and the USU Western and English Equestrian Teams. Jeremy is currently a freshman studying Animal, Dairy, and Veterinary Science, Biotechnology Emphasis with minors in Chemistry and Biology.

In His Words: The Author on His Writing

Whenever I presented at my FFA chapter’s agricultural education events, I received strange answers about what chickens give us, such as milk and seeds. So, I asked myself, “Why aren’t schools prioritizing students knowing where their food comes from like they are the arts or history?” Having been through agricultural education programs myself, I wanted to explore the possibility of requiring these programs, as they develop positive life skills and responsibility aside from agricultural understanding.

This essay was composed in May 2022 and uses MLA documentation.

THE SMELL OF WET SOIL HUNG TIGHTLY in the humid air. Small weeds crept across the concrete path, their leaves reaching up to catch the water from the hose as I carefully watered each plant. The desert sun shone brightly down through the cream panels, warming my back and illuminating each leaf like a stained-glass window. The fans carried a gentle breeze throughout. My jeans brushed against the wood of the tables that are worn smooth by the many years of use from students who cared for this greenhouse before me. I performed the tasks for the day like clockwork: measuring plants, transplanting seedlings, trimming, updating inventory, preparing orders, and ensuring the greenhouse conditions were at homeostasis. I can’t believe this is my last day in class before I graduate.

For many public high school students, this, unfortunately, is not a common memory. Gymnasiums, whiteboards, calculators, tile floors, class bells, and uniformly arranged rows of desks dominate the mind. Universal public education began in the United States as early as the 1830s with “common schools” that would deliver a liberal education of “the ‘three R’s’ (reading, writing, arithmetic), along with other subjects such as history, geography, grammar, and rhetoric” (“History and Evolution…”). Modern-day public education continues to retain these basic components, preparing students for successful careers in the workforce by developing relevant life skills. General education is the program designed to ensure that

students hone life skills…including oral and written communication, teamwork and collaboration and problem-solving,” which consistently rank amongst the “top life skills valued by employers in the United States and globally. (Crews et al.)

In an attempt to define these critical mathematics and English literacy objectives, the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) and the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices (NGA Center) established the Common Core in 2009 (“About the Standards”). The Common Core is an attempt to federally standardize the skills and knowledge necessary for students to succeed in college or the workforce. Currently, 41 states, the District of Columbia, four U.S. territories, and the Department of Defense Education Activity have voluntarily adopted the Common Core, establishing a rudimentary set of general education requirements nationally (“About the Standards”).

Targeted skills of general education are often evaluated through standardized exams or evaluation rubrics derived from Common Core standards. Current Common Core anchor standards include reading and comprehension of diverse, complex texts; writing argumentative, informative, and narrative texts for a range of tasks, purposes, and audiences; research and evidence-based reasoning; and speaking and listening skills (“Common Core State Standards…”). Despite the Common Core emphasizing strong language and mathematical literacy, it fails to develop other life skills that are critical in the workplace, such as leadership and public speaking. In order to ensure that students receive an education that best prepares them for life, secondary schools ought to incorporate additional general education requirements into curricula that target life skill development besides English and mathematical literacy—the unlikely solution being agricultural education.

Agricultural education is a means through which students can explore a variety of subjects within the agricultural industry, from welding to animal science. Agriculture classes are commonly offered as elective or science credits in secondary education systems, and they primarily focus on developing specialized skills via experiential and hands-on learning. As agriculture is a vast field, students can pursue programs and certifications in—but not limited to—plant science, greenhouse management, animal science, livestock management, welding, agribusiness, agricultural mechanics, veterinary medicine, agronomy, forestry, and many more.

However, agricultural education is not only limited to the traditional school environment; extracurricular programming provides applied learning opportunities beyond the classroom. The two primary agricultural youth organizations that supplement curricula in the United States are the 4-H and FFA programs. These organizations allow youth to explore their interests by planning further, executing, and keeping detailed records for a project of their choice. 4-H and FFA projects provide experiential learning for youth in specialized facets of the agricultural industry, often involving responsibility and management of financial resources. Although animal husbandry and market projects are what commonly come to mind, 4-H and FFA offer great opportunities to grow skills in engineering, science, home economics, culinary arts, and public speaking. Further, these agricultural programs encourage youth to participate in community service and leadership positions, with responsibilities of planning, collaboration with stakeholders, communication, conduct of meetings, and community service projects. While both programs provide quality access to agricultural education, 4-H and FFA differ from one another in their structure and realized impacts on youth.

The 4-H Program

The 4-H program is an international youth organization that advocates to “make the best better” through positive youth development and experiential, project-based learning. Founded in 1902 to originally improve farming practices, the organization has grown into a vast “network of more than 6 million youth, 611,800 volunteers, [and] 3,500 professionals” delivered in nearly every county across the United States (“What Is 4-H?”). The success of the 4-H program is founded on the partnership and collaboration of the United States Department of Agriculture, National 4-H Council, and Cooperative Extension.

The structure of the 4-H program begins with the land-grant university of a specific state. For example, Utah State University is the land-grant university for the state of Utah. The land-grant university has an extension office in nearly every county of their respective state, each containing a network of extension and 4-H educators whose mission is to conveniently provide the knowledge and research of the university to their community. The specialization of the extension agents is targeted toward the specific needs of the community, ranging from Family and Consumer Sciences to Agronomy. However, nearly all counties have 4-H Coordinators and 4-H Youth Development Professionals that deliver curriculum from the National 4-H Council to their counties. 4-H club volunteers work closely with extension agents to provide hands-on learning opportunities to their 4-H youth members.

Of course, 4-H primarily takes place as an extracurricular activity outside of normal school hours. This exclusivity tends to limit accessibility for families who may not have the support or financial resources to arrange for after-school commitments. In order to combat this accessibility issue, land-grant universities are beginning to integrate the 4-H program into public schools as actual classes. Offering in-school hours where students can earn credit for agricultural education and involvement is gaining traction in many school districts across the nation. For example, the 4-H Juntos program has recently been launched in a few of Idaho’s Twin Falls and Jerome County public schools.

According to Suzann Dolecheck, former Twin Falls County 4-H Youth Development Educator, the Juntos program “provides at-risk…students and their families with the knowledge, skills, and resources to ensure high school graduation and increase awareness to post-secondary education opportunities,” with the University of Idaho largely focusing on the Latinx community of Southern Idaho and the Native American tribes of Northern Idaho (Dolecheck). The program is funded externally by the CYFAR (Children, Youth and Family at Risk) federal grant as well as through the University of Idaho Extension (Dolecheck). 4-H Juntos is integrated into public schools as an actual course taught by a Juntos coordinator from the University of Idaho county extension over multiple periods of the school day, making it accessible to those in marginalized and minority communities. Youth receive personalized advising from their coordinator, life skills in classroom activities through 4-H programming, family and community engagement, and access to 4-H summer leadership camps. The fledgling Juntos program is hopefully expected to expand to surrounding counties in the future.

By sowing greater access to agricultural education through the 4-H program as an extracurricular activity and a class students can take, youth can reap life skills more successfully. An Idaho 4-H Impact Study published in the Journal of Extension reports that 4-H youth are more likely to perform well in academia, more likely to hold leadership positions, more likely to acquire independent living skills, and nearly half as likely to engage in risky behaviors compared to their non-4-H counterparts (Goodwin et al.); many of these data showed great statistical significance. Youth participating in the 4-H program tend to obtain valuable life skills more efficiently through the experiential education the 4-H program provides. Thus, agricultural education seems to succeed in facets that the Common Core and general education fail to address.

The National FFA Organization

The National FFA Organization is another primary leader like 4-H that provides youth opportunities in agricultural education. However, the FFA program has already been successfully integrated into the United States public school system as a partner to secondary agricultural education. The National FFA Organization, founded in 1928, currently has “735,038 FFA members, aged 12-21, in 8,817 chapters in all 50 states, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands” in grades 7 to 12 and through college (“Our Membership”). Students enrolled in agricultural education courses take a three-component approach to ensure proper skill and leadership development.

Agricultural education initiative in public schools is founded upon the Three-Component Model: Classroom and Laboratory, Supervised Agricultural Experience (SAE), and FFA (“Agricultural Education”). Students receive education in the classroom and laboratory that lays a foundation for their SAE project, through which they gain specialized skills in an experiential learning process of their choice. Projects range from agricultural science to raising market steers, whose management requires accurate record keeping, financial planning, and writing. The FFA program supplements the classroom and SAE education by providing opportunities for personal growth through competitive events, leadership conventions, career exploration, and service opportunities.

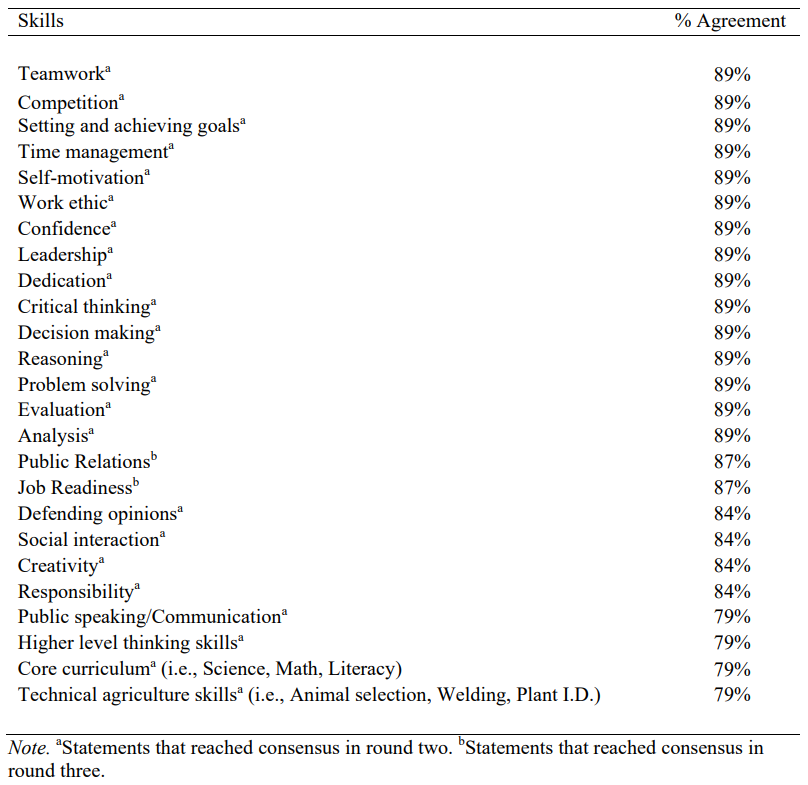

FFA offers two forms of competitive events that target career-relevant and leadership skills: Career Development Events (CDEs) and Leadership Development Events (LDEs). These competitions encompass livestock judging, meats evaluation and technology, veterinary science, floriculture, public speaking, employment skills, agribusiness, and many more. According to a study conducted by Lundry et al. on 30 agricultural education teachers, FFA competitive events are incredibly efficacious for professional and life skill development. Participants were asked to rate their agreement on a scale of 0-6 regarding the efficacy of FFA CDEs. The results of Round Two and Three from the study are summarized in the table below:

The study demonstrates that FFA Career Development Events (CDEs) and Leadership Development Events have positive impact on youth. The high agreement ratings reflect intentional advancement of life skills, such as leadership and teamwork, that the Common Core and general education fail to address. FFA works in conjunction with public agricultural education to ensure that students have access to these opportunities inside and outside of the classroom, allowing students of all socio-economic backgrounds to participate. However, these opportunities are only limited to schools that have the infrastructure to offer agricultural courses.

Discussion

Through the 4-H Program and the National FFA Organization, agricultural education provides immense opportunities for positive youth development and a successful career in the workforce. To provide our students with the best opportunities for a successful life, agricultural education should be incorporated into the general education curriculum.

However, some barriers block agricultural instruction from being integrated into general education programs. Agriculture teacher retention, financial strain, and accessibility between urban and rural communities pose logistical challenges for secondary public schools.

A study by Lemons et al. investigates why agriculture teachers may leave their profession. The study interviewed nine previous teachers who must have taught for at least one full academic year and have left the profession voluntarily—not due to coercion, termination, or non-renewal. Data analysis revealed five significant reasons for leaving the profession: passions for the profession, alternative opportunities, expectations, retrospective burdens, and people (Lemons et al.). Although passion and previous experience in agricultural education and/or FFA are factors that retain instructors, many “teachers do not receive adequate compensation for the work they do” and lack pre-services that prepare them for their careers in agricultural education (Lemons et al.).

Tackling the issue of teacher retention is complex, and no one solution will fit all schools. However, agriculture teachers are essential to maintaining quality programming, as they are the face of agriculture in the classroom and many students’ first experience with it. The primary reason why teachers leave agricultural education lies not in teaching itself but rather in a lack of administrative support. These teachers do not receive proper resources or compensation for their work, resulting in frustration with the administration and eventual resignation. Applying for external grants can provide additional resources to agricultural educators, helping relieve strained school budgets. Regarding compensation, schools can offer more benefits to teachers, which can include—but are not limited to—additional vacation days or paid time for chaperoning FFA activities outside of normal school hours.

Besides teacher retention, the addition of agriculture programs could place even more financial strain on school budgets. Hiring more teachers and broadening course offerings could complicate matters in schools without pre-existing agriculture programs. As each district and school allocate fiscal assets differently, the solution to this issue is beyond the scope of this essay. Yet, the positive impact of agricultural education on life skill development is worth the investment in the students’ future. Funding does not need to come directly from taxpayer money either; it can be sourced externally via grants and organizations, such as 4-H Juntos in Idaho.

Aside from employment issues and budgeting concerns, accessibility to such programs in schools varies drastically between urban and rural populations. Rural schools tend to have easier access to land, livestock, and facilities to supplement classroom education that urban communities lack. As a result, rural schools tend to already have agricultural programs in place that can readily accommodate a new general education requirement. Therefore, the primary issue lies within urban communities; yet it is these communities whose marginalized groups are in most need of the life skills that agricultural education cultivates.

Animal rearing and crop farming represent only a minor fraction of the vast field of agriculture. Fortunately, this is reflected in modern agricultural education. Many facets of agriculture do not require state-of-the-art animal facilities, such as nutrition and soil science. Courses covering these topics can be taught in the classrooms of urban cities with as little as a bag of soil and a microscope. Expanding agricultural programs to urban schools will also provide greater access to 4-H and/or FFA programming, through which youth can gain leadership, financial, and other life skills through their experiential learning platforms. Integrating more affirmative-action agricultural programs into urban general education, like 4-H Juntos, would immensely benefit students of marginalized communities as well.

Of course, we still have a long way to go before agricultural education can be required nationally in general education curricula. The challenges of teacher retention, budgeting, and rural-urban accessibility slow down progress. However, the goal of public education is to develop essential life skills in youth so that they can be successful in the workplace and life.

Public speaking, leadership, teamwork, and problem-solving are some of the most highly desired skills in the professional workforce (Crews et al.). Yet, the current general education program fails to target these critical skills. Agricultural education—in conjunction with the 4-H Program and the National FFA Organization—ultimately provides a strong experiential learning platform through which students develop essential life skills that that lack in classroom Common Core. Thus, agricultural education ought to be integrated into general education requirements.

Growing the leaders of the future in our public education system should be a top priority. Despite the financial and accessibility issues, developing the infrastructure to require agricultural education in secondary schools is worth the investment. Before we know it, our students will inherit complicated global challenges like climate change and producing more food with fewer resources. The least we can do is ensure they have the skills necessary to become the leaders of tomorrow.

For more information regarding the 4-H and FFA programs, please visit the following websites:

- The 4-H Program: https://4-h.org/

- The National FFA Organization: https://www.ffa.org/

- Utah State University Extension: https://extension.usu.edu/

Works Cited

“About the Standards.” Common Core State Standards Initiative About the Standards Comments, Common Core State Standards Initiative, 2022, http://www.corestandards.org/about-the-standards/.

“Agricultural Education.” National FFA Organization, The National FFA Organization, 14 Jan. 2019, https://www.ffa.org/agricultural- education/#:~:text=Agricultural%20education%20first%20became%20a,states%20and% 20three%20U.%20S.%20territories.

“Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects.” Common Core State Standards Initiative.

Crews, Kimberly, et al. “Developing Culturally Relevant Rubrics to Assess General Education Learning Outcomes.” Journal of Applied Business and Economics, vol. 22, no. 11, 2020, https://doi.org/10.33423/jhetp.v20i12.3781.

Dolecheck, Suzann. Email Interview. April 27, 2022.

Goodwin, Jeff, et al. “Idaho 4-H Impact Study.” Journal of Extension, vol. 43, no. 4, Aug. 2005.

“History and Evolution of Public Education in the US.” Center on Education Policy, 2020.

Lemons, Laura L., et al. “Factors Contributing to Attrition as Reported by Leavers of Secondary Agriculture Programs.” Journal of Agricultural Education, vol. 56, no. 4, 2015, pp. 17– 30., https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2015.04017.

Lundry, Jerrod, et al. “Benefits of Career Development Events as Perceived by School-Based, Agricultural Education Teachers.” Journal of Agricultural Education, vol. 56, no. 1, 2015, pp. 43–57., https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2015.01043.

“Our Membership.” National FFA Organization, The National FFA Organization, 16 Dec. 2021, https://www.ffa.org/our- membership/#:~:text=The%20National%20FFA%20Organization%20provides,seven%2 0through%2012%20and%20college.

“What Is 4-H?” Utah State University Salt Lake County Extension, Utah State University Extension, https://extension.usu.edu/saltlake/4h/basics#:~:text=As%20a%20part%20of%20the,learni ng%20and%20learning%20in%20fun.