44 The Light-Dependent Reactions of Photosynthesis

Jung Choi; Mary Ann Clark; and Matthew Douglas

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Explain how plants absorb energy from sunlight

- Describe short and long wavelengths of light

- Describe how and where photosynthesis takes place within a plant

How can light energy be used to make food? When a person turns on a lamp, electrical energy becomes light energy. Like all other forms of kinetic energy, light can travel, change form, and be harnessed to do work. In the case of photosynthesis, light energy is converted into chemical energy, which photoautotrophs use to build basic carbohydrate molecules (Figure 8.9). However, autotrophs only use a few specific wavelengths of sunlight.

What Is Light Energy?

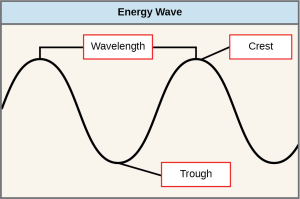

The sun emits an enormous amount of electromagnetic radiation (solar energy in a spectrum from very short gamma rays to very long radio waves). Humans can see only a tiny fraction of this energy, which we refer to as “visible light.” The manner in which solar energy travels is described as waves. Scientists can determine the amount of energy of a wave by measuring its wavelength (shorter wavelengths are more powerful than longer wavelengths)—the distance between consecutive crest points of a wave. Therefore, a single wave is measured from two consecutive points, such as from crest to crest or from trough to trough (Figure 8.10).

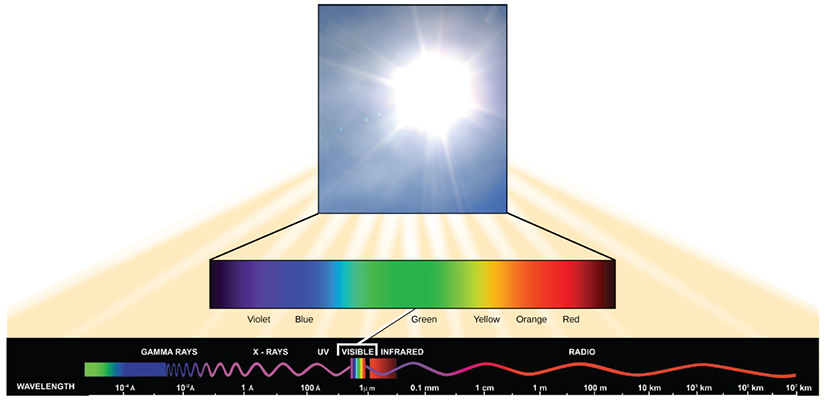

Visible light constitutes only one of many types of electromagnetic radiation emitted from the sun and other stars. Scientists differentiate the various types of radiant energy from the sun within the electromagnetic spectrum. The electromagnetic spectrum is the range of all possible frequencies of radiation (Figure 8.11). The difference between wavelengths relates to the amount of energy carried by them.

Each type of electromagnetic radiation travels at a particular wavelength. The longer the wavelength, the less energy it carries. Short, tight waves carry the most energy. This may seem illogical, but think of it in terms of a piece of moving heavy rope. It takes little effort by a person to move a rope in long, wide waves. To make a rope move in short, tight waves, a person would need to apply significantly more energy.

The electromagnetic spectrum (Figure 8.11) shows several types of electromagnetic radiation originating from the sun, including X-rays and ultraviolet (UV) rays. The higher-energy waves can penetrate tissues and damage cells and DNA, which explains why both X-rays and UV rays can be harmful to living organisms.

Absorption of Light

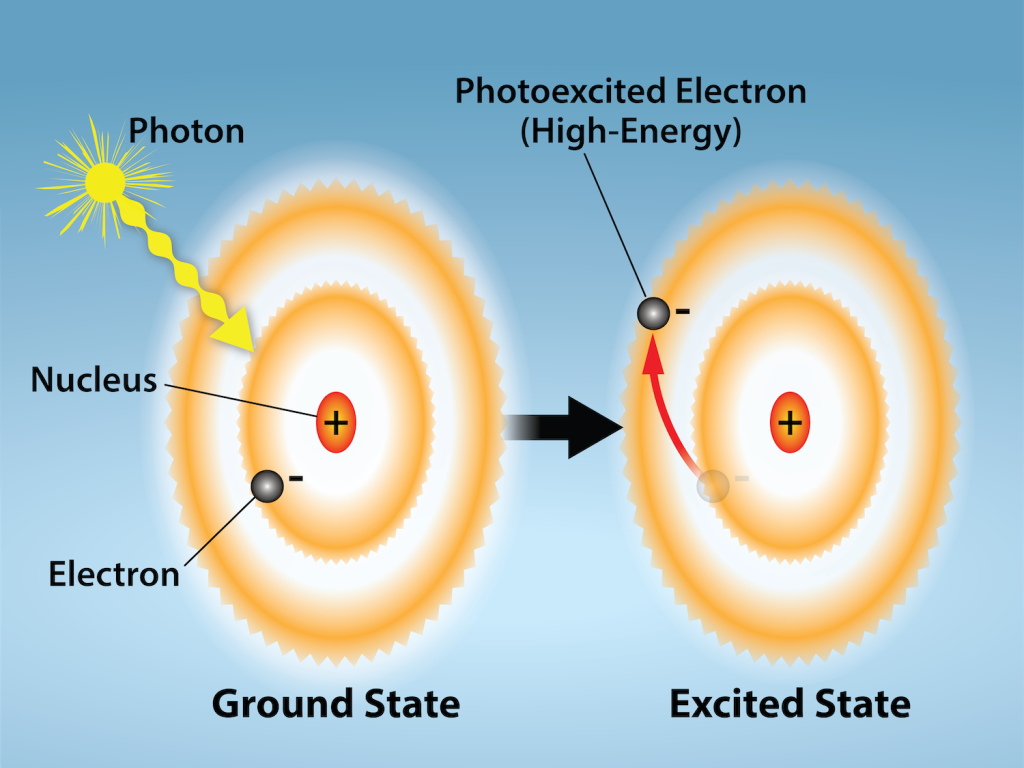

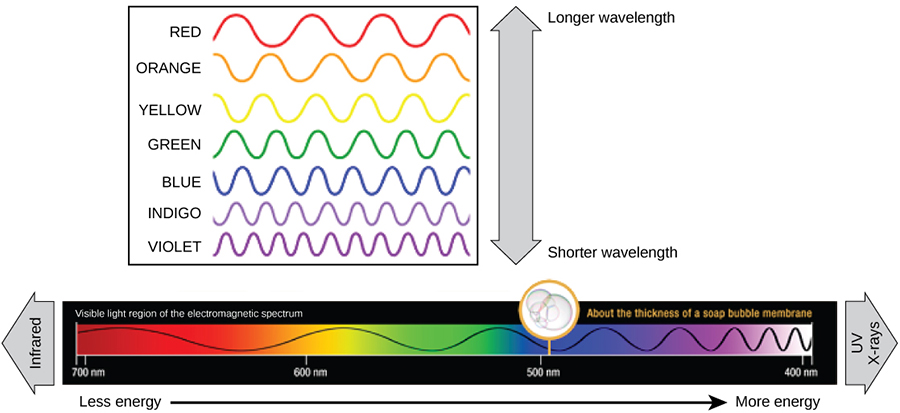

Light energy initiates the process of photosynthesis when pigments absorb specific wavelengths of visible light. Organic pigments, whether in the human retina or the chloroplast thylakoid, have a narrow range of energy levels that they can absorb. Energy levels lower than those represented by red light are insufficient to raise an orbital electron to an excited (quantum) state. Energy levels higher than those in blue light will physically tear the molecules apart, in a process called bleaching. Our retinal pigments can only “see” (absorb) wavelengths between 700 nm and 400 nm of light, a spectrum that is therefore called visible light. For the same reasons, plants, pigment molecules absorb only light in the wavelength range of 700 nm to 400 nm; plant physiologists refer to this range for plants as photosynthetically active radiation.

The visible light seen by humans as white light actually exists in a rainbow of colors. Certain objects, such as a prism or a drop of water, disperse white light to reveal the colors to the human eye. The visible light portion of the electromagnetic spectrum shows the rainbow of colors, with violet and blue having shorter wavelengths, and therefore higher energy. At the other end of the spectrum toward red, the wavelengths are longer and have lower energy (Figure 8.13).

Understanding Pigments

Different kinds of pigments exist, and each absorbs only specific wavelengths (colors) of visible light. Pigments reflect or transmit the wavelengths they cannot absorb, making them appear a mixture of the reflected or transmitted light colors.

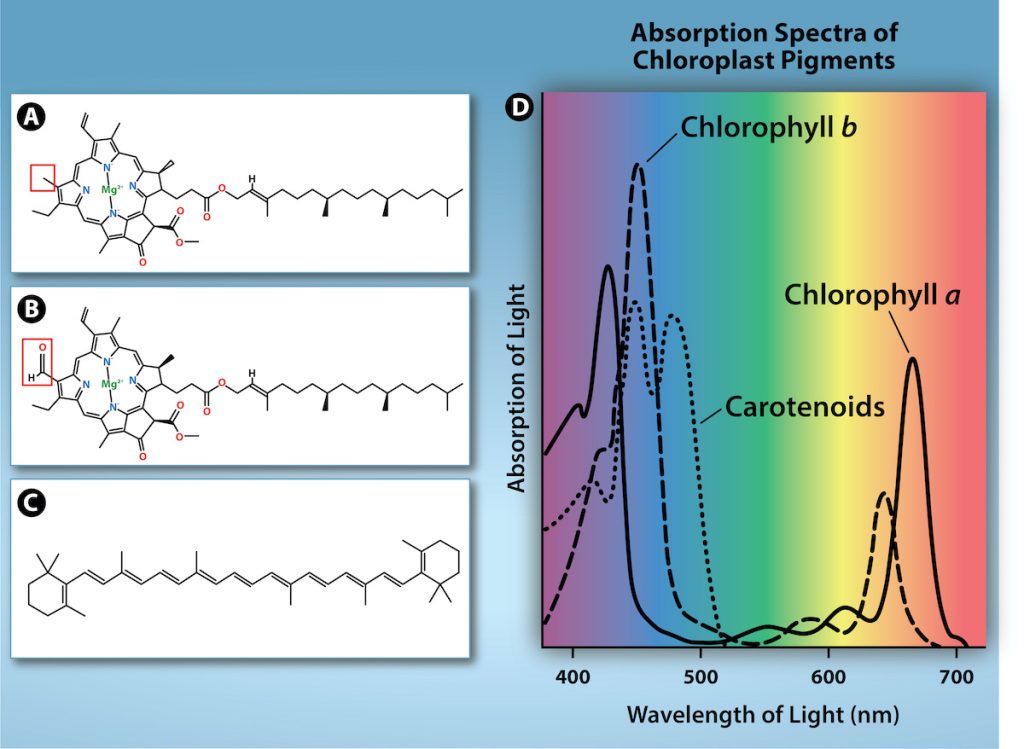

Chlorophylls and carotenoids are the two major classes of photosynthetic pigments found in plants and algae; each class has multiple types of pigment molecules. There are five major chlorophylls: a, b, c, and d and a related molecule found in prokaryotes called bacteriochlorophyll. Chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b are found in higher plant chloroplasts and will be the focus of the following discussion.

With dozens of different forms, carotenoids are a much larger group of pigments. The carotenoids found in fruit—such as the red of tomato (lycopene), the yellow of corn seeds (zeaxanthin), or the orange of an orange peel (β-carotene)—are used as advertisements to attract seed dispersers. In photosynthesis, carotenoids function as photosynthetic pigments that are very efficient molecules for the disposal of excess energy. When a leaf is exposed to full sun, the light-dependent reactions are required to process an enormous amount of energy; if that energy is not handled properly, it can do significant damage. Therefore, many carotenoids reside in the thylakoid membrane, absorb excess energy, and safely dissipate that energy as heat.

Each type of pigment can be identified by the specific pattern of wavelengths it absorbs from visible light: This is termed the absorption spectrum. The graph in Figure 8.14 shows the absorption spectra for chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and a type of carotenoid pigment called β-carotene (which absorbs blue and green light). Notice how each pigment has a distinct set of peaks and troughs, revealing a highly specific pattern of absorption. Chlorophyll a absorbs wavelengths from either end of the visible spectrum (blue and red), but not green. Because green is reflected or transmitted, chlorophyll appears green. Carotenoids absorb in the short-wavelength blue region, and reflect the longer yellow, red, and orange wavelengths.

Many photosynthetic organisms have a mixture of pigments, and by using these pigments, the organism can absorb energy from a wider range of wavelengths. Not all photosynthetic organisms have full access to sunlight. Some organisms grow underwater where light intensity and quality decrease and change with depth. Other organisms grow in competition for light. Plants on the rainforest floor must be able to absorb any bit of light that comes through, because the taller trees absorb most of the sunlight and scatter the remaining solar radiation (Figure 8.15).

When studying a photosynthetic organism, scientists can determine the types of pigments present by generating absorption spectra. An instrument called a spectrophotometer can differentiate which wavelengths of light a substance can absorb. Spectrophotometers measure transmitted light and compute from it the absorption. By extracting pigments from leaves and placing these samples into a spectrophotometer, scientists can identify which wavelengths of light an organism can absorb. Additional methods for the identification of plant pigments include various types of chromatography that separate the pigments by their relative affinities to solid and mobile phases.

How Light-Dependent Reactions Work

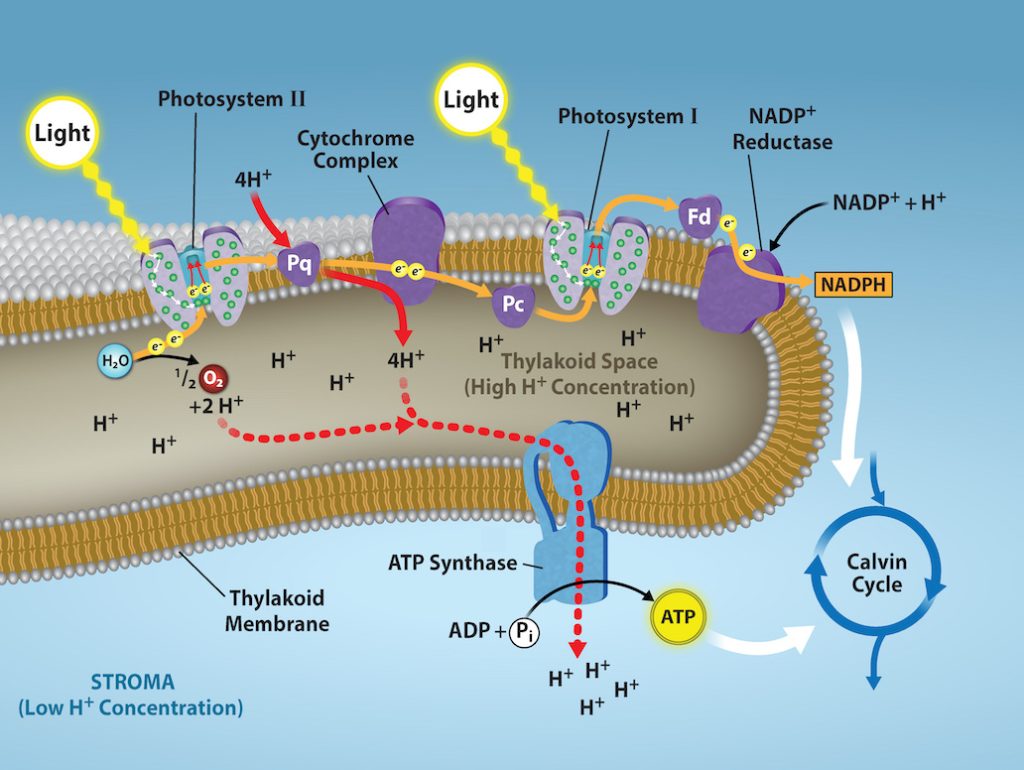

The overall function of light-dependent reactions is to convert solar energy into chemical energy in the form of NADPH and ATP. This chemical energy supports the light-independent reactions and fuels the assembly of sugar molecules. The light-dependent reactions are depicted in Figure 8.16. Protein complexes and pigment molecules work together to produce NADPH and ATP. The numbering of the photosystems is derived from the order in which they were discovered, not in the order of the transfer of electrons.

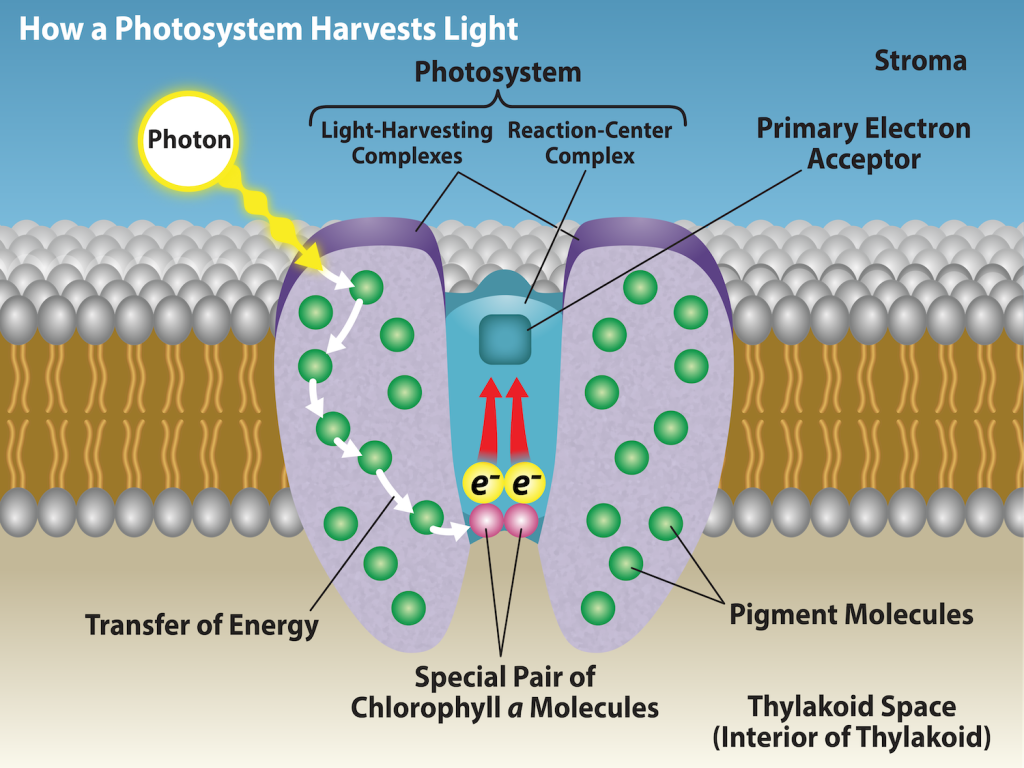

The actual step that converts light energy into chemical energy takes place in a multiprotein complex called a photosystem, two types of which are found embedded in the thylakoid membrane: photosystem II (PSII) and photosystem I (PSI) (Figure 8.17). The two complexes differ on the basis of what they oxidize (that is, the source of the low-energy electron supply) and what they reduce (the place to which they deliver their energized electrons).

Both photosystems have the same basic structure: a number of antenna proteins to which the chlorophyll molecules are bound surround the reaction center where the photochemistry takes place. Each photosystem is serviced by the light-harvesting complex, which passes energy from sunlight to the reaction center; it consists of multiple antenna proteins that contain a mixture of 300 to 400 chlorophyll a and b molecules as well as other pigments like carotenoids. The absorption of a single photon or distinct quantity or “packet” of light by any of the chlorophylls pushes that molecule into an excited state. In short, the light energy has now been captured by biological molecules but is not stored in any useful form yet. The energy is transferred from chlorophyll to chlorophyll until eventually (after about a millionth of a second), it is delivered to the reaction center. Up to this point, only energy has been transferred between molecules, not electrons.

Visual Connection

What is the initial source of electrons for the chloroplast electron transport chain?

- water

- oxygen

- carbon dioxide

- NADPH

The reaction center contains a pair of chlorophyll a molecules with a special property. Those two chlorophylls can undergo oxidation upon excitation; they can actually give up an electron in a process called a photoact. It is at this step in the reaction center during photosynthesis that light energy is converted into an excited electron. All of the subsequent steps involve getting that electron onto the energy carrier NADPH for delivery to the Calvin cycle where the electron is deposited onto carbon for long-term storage in the form of a carbohydrate. PSII and PSI are two major components of the photosynthetic electron transport chain, which also includes the cytochrome complex. The cytochrome complex, an enzyme composed of two protein complexes, transfers the electrons from the carrier molecule plastoquinone (Pq) to the protein plastocyanin (Pc), thus enabling both the transfer of protons across the thylakoid membrane and the transfer of electrons from PSII to PSI.

The reaction center of PSII (called P680) delivers its high-energy electrons, one at the time, to the primary electron acceptor, and through the electron transport chain (Pq to cytochrome complex to plastocyanine) to PSI. P680’s missing electron is replaced by extracting a low-energy electron from water; thus, water is “split” during this stage of photosynthesis, and PSII is re-reduced after every photoact. Splitting one H2O molecule releases two electrons, two hydrogen atoms, and one atom of oxygen. However, splitting two molecules is required to form one molecule of diatomic O2 gas. About 10 percent of the oxygen is used by mitochondria in the leaf to support oxidative phosphorylation. The remainder escapes to the atmosphere where it is used by aerobic organisms to support respiration.

As electrons move through the proteins that reside between PSII and PSI, they lose energy. This energy is used to move hydrogen atoms from the stromal side of the membrane to the thylakoid lumen. Those hydrogen atoms, plus the ones produced by splitting water, accumulate in the thylakoid lumen and will be used synthesize ATP in a later step. Because the electrons have lost energy prior to their arrival at PSI, they must be re-energized by PSI, hence, another photon is absorbed by the PSI antenna. That energy is relayed to the PSI reaction center (called P700). P700 is oxidized and sends a high-energy electron to NADP+ to form NADPH. Thus, PSII captures the energy to create proton gradients to make ATP, and PSI captures the energy to reduce NADP+ into NADPH. The two photosystems work in concert, in part, to guarantee that the production of NADPH will roughly equal the production of ATP. Other mechanisms exist to fine-tune that ratio to exactly match the chloroplast’s constantly changing energy needs.

Generating an Energy Carrier: ATP

As in the intermembrane space of the mitochondria during cellular respiration, the buildup of hydrogen ions inside the thylakoid lumen creates a concentration gradient. The passive diffusion of hydrogen ions from high concentration (in the thylakoid lumen) to low concentration (in the stroma) is harnessed to create ATP, just as in the electron transport chain of cellular respiration. The ions build up energy because of diffusion and because they all have the same electrical charge, repelling each other.

To release this energy, hydrogen ions will rush through any opening, similar to water jetting through a hole in a dam. In the thylakoid, that opening is a passage through a specialized protein channel called the ATP synthase. The energy released by the hydrogen ion stream allows ATP synthase to attach a third phosphate group to ADP, which forms a molecule of ATP (Figure 8.17). The flow of hydrogen ions through ATP synthase is called chemiosmosis because the ions move from an area of high to an area of low concentration through a semi-permeable structure of the thylakoid.

Link to Learning

Visit this site and click through the animation to view the process of photosynthesis within a leaf.