26 Active Transport

Jung Choi; Mary Ann Clark; and Matthew Douglas

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Understand how electrochemical gradients affect ions

- Distinguish between primary active transport and secondary active transport

Transmembrane Protein Structure and Functions

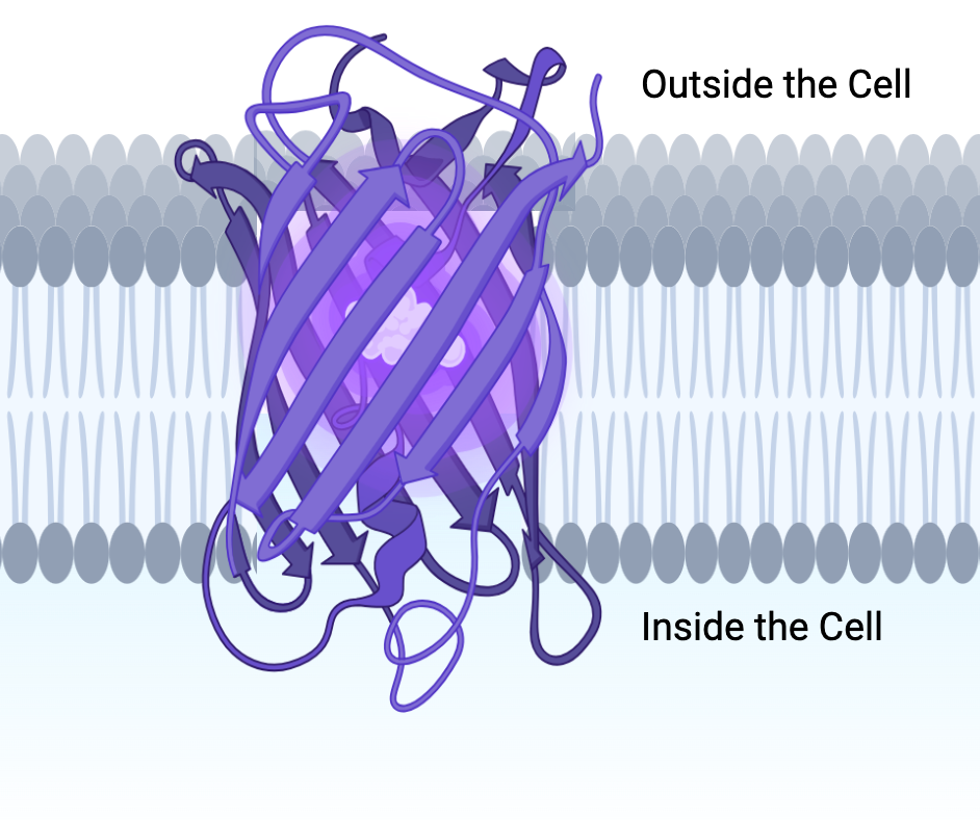

The ribbon structure of a transmembrane protein is a specialized form of the ribbon diagram used to depict the architecture of proteins that span biological membranes. These proteins are embedded within the lipid bilayer and often have regions that interact with both the hydrophobic core of the membrane and the aqueous environments on either side.

Here’s how the ribbon structure of a transmembrane protein is typically represented:

1. Transmembrane Helices:

- Alpha Helices: The most common structural motif in transmembrane proteins. These helices are depicted as cylindrical or coiled ribbons passing through the lipid bilayer.

- The helices are oriented vertically (perpendicular to the plane of the membrane) in the diagram, showing how they span the membrane.

- They are usually depicted in a way that emphasizes their interaction with the hydrophobic core of the lipid bilayer. The helices are often colored or shaded to distinguish the transmembrane segments from the extracellular or intracellular regions.

2. Extracellular and Intracellular Loops:

- The loops that connect the transmembrane helices are shown as thinner ribbons or lines.

- Extracellular Loops: These loops extend from the transmembrane helices into the extracellular space, often involved in ligand binding or signaling.

- Intracellular Loops: These loops project into the cytoplasm and are frequently involved in signaling pathways or interactions with other intracellular molecules.

- These loops can vary in length and complexity, and they are key to the protein’s function.

3. Beta Sheets:

- Less common than alpha helices in transmembrane regions, but when present, they can form beta barrels. These are depicted as broad, curved ribbons forming a cylindrical structure that allows the sheet to span the membrane.

- Beta barrels create a pore or channel through the membrane, and the ribbon diagram often emphasizes the orientation of the strands (with arrows pointing in the direction of the peptide chain).

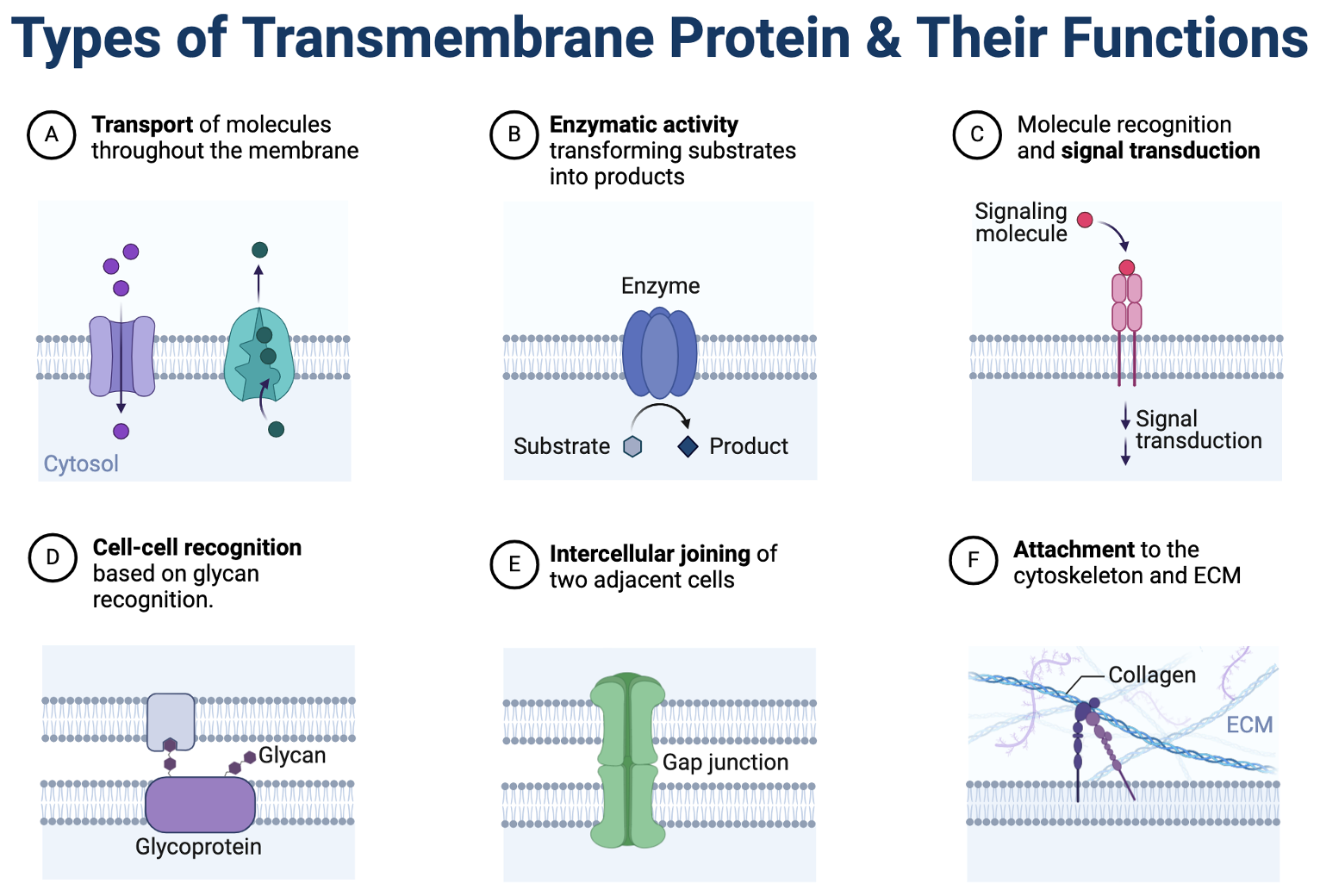

Transmembrane proteins are integral membrane proteins that span the lipid bilayer, playing crucial roles in various cellular processes. In the Imagine below are a six different types of transmembrane proteins all having a important and unique function for the cell.

Active transport mechanisms require the cell’s energy, usually in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). If a substance must move into the cell against its concentration gradient—that is, if the substance’s concentration inside the cell is greater than its concentration in the extracellular fluid (and vice versa)—the cell must use energy to move the substance. Some active transport mechanisms move small-molecular weight materials, such as ions, through the membrane. Other mechanisms transport much larger molecules.

Electrochemical Gradient

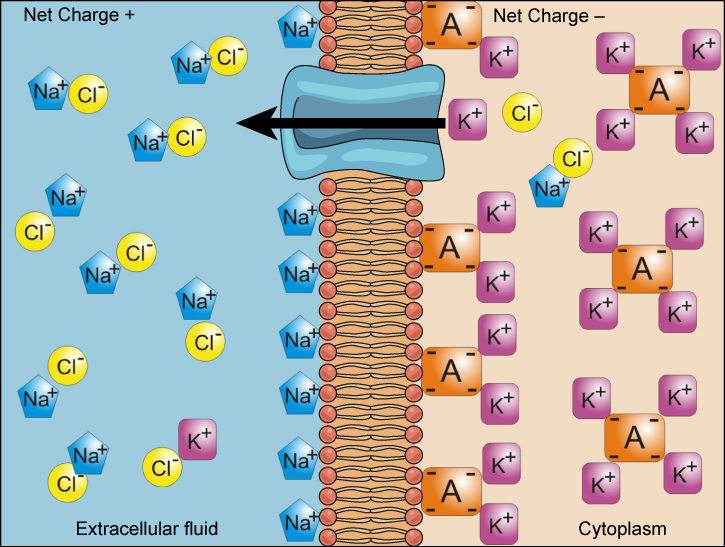

We have discussed simple concentration gradients—a substance’s differential concentrations across a space or a membrane—but in living systems, gradients are more complex. Because ions move into and out of cells and because cells contain proteins that do not move across the membrane and are mostly negatively charged, there is also an electrical gradient, a difference of charge, across the plasma membrane. The interior of living cells is electrically negative with respect to the extracellular fluid in which they are bathed, and at the same time, cells have higher concentrations of potassium (K+) and lower concentrations of sodium (Na+) than the extracellular fluid. Thus in a living cell, the concentration gradient of Na+ tends to drive it into the cell, and its electrical gradient (a positive ion) also drives it inward to the negatively charged interior. However, the situation is more complex for other elements such as potassium. The electrical gradient of K+, a positive ion, also drives it into the cell, but the concentration gradient of K+ drives K+ out of the cell (Figure 5.16). We call the combined concentration gradient and electrical charge that affects an ion its electrochemical gradient.

Visual Connection

Injecting a potassium solution into a person’s blood is lethal. This is how capital punishment and euthanasia subjects die. Why do you think a potassium solution injection is lethal?

Moving Against a Gradient

To move substances against a concentration or electrochemical gradient, the cell must use energy. This energy comes from ATP generated through the cell’s metabolism. Active transport mechanisms, or pumps, work against electrochemical gradients. Small substances constantly pass through plasma membranes. Active transport maintains concentrations of ions and other substances that living cells require in the face of these passive movements. A cell may spend much of its metabolic energy supply maintaining these processes. (A red blood cell uses most of its metabolic energy to maintain the imbalance between exterior and interior sodium and potassium levels that the cell requires.) Because active transport mechanisms depend on a cell’s metabolism for energy, they are sensitive to many metabolic poisons that interfere with the ATP supply.

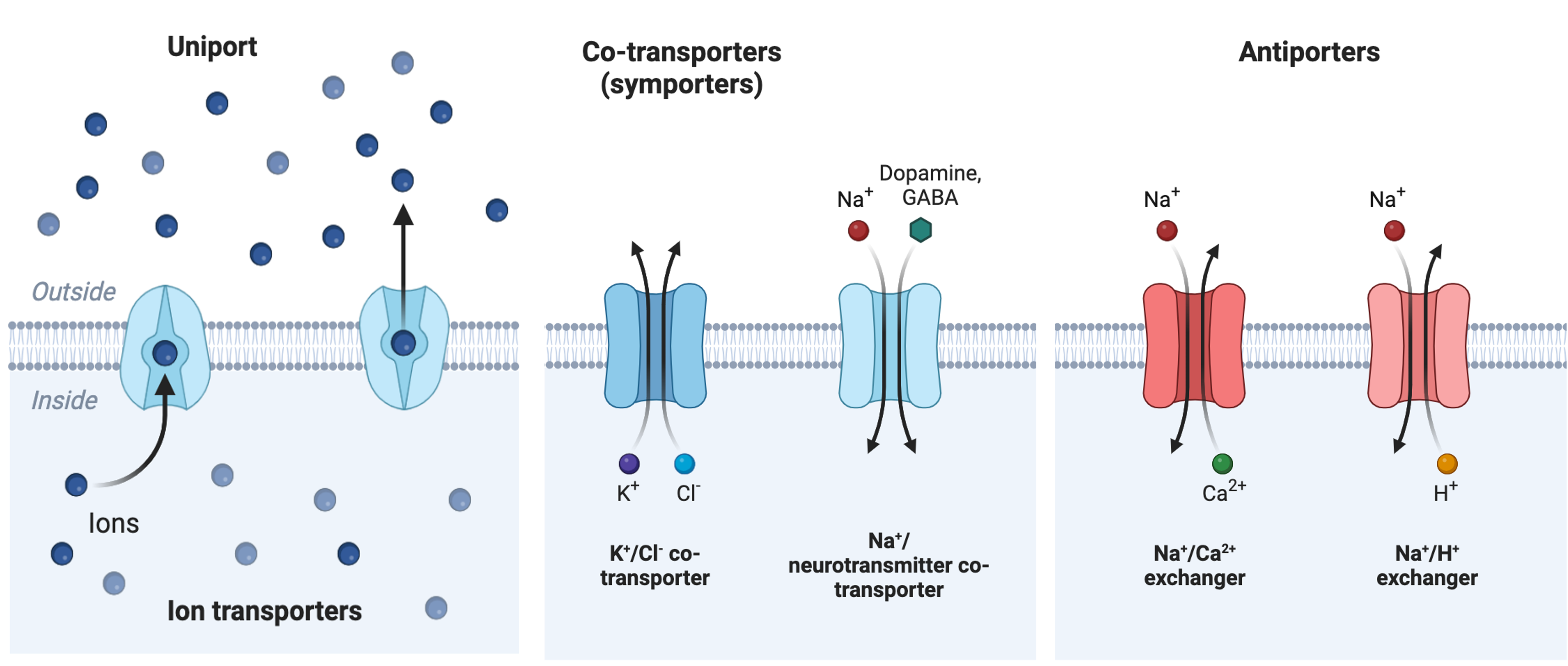

Two mechanisms exist for transporting small-molecular weight material and small molecules. Primary active transport moves ions across a membrane and creates a difference in charge across that membrane, which is directly dependent on ATP. Secondary active transport does not directly require ATP: instead, it is the movement of material due to the electrochemical gradient established by primary active transport.

Carrier Proteins for Active Transport

Primary Active Transport

The primary active transport that functions with the active transport of sodium and potassium allows secondary active transport to occur. The second transport method is still active because it depends on using energy as does primary transport (Figure 5.18).

One of the most important pumps in animal cells is the sodium-potassium pump (Na+-K+ ATPase), which maintains the electrochemical gradient (and the correct concentrations of Na+ and K+) in living cells. The sodium-potassium pump moves K+ into the cell while moving Na+ out at the same time, at a ratio of three Na+ for every two K+ ions moved in. The Na+-K+ ATPase exists in two forms, depending on its orientation to the cell’s interior or exterior and its affinity for either sodium or potassium ions. The process consists of the following six steps.

- With the enzyme oriented toward the cell’s interior, the carrier has a high affinity for sodium ions. Three ions bind to the protein.

- The protein carrier hydrolyzes ATP and a low-energy phosphate group attaches to it.

- As a result, the carrier changes shape and reorients itself toward the membrane’s exterior. The protein’s affinity for sodium decreases and the three sodium ions leave the carrier.

- The shape change increases the carrier’s affinity for potassium ions, and two such ions attach to the protein. Subsequently, the low-energy phosphate group detaches from the carrier.

- With the phosphate group removed and potassium ions attached, the carrier protein repositions itself toward the cell’s interior.

- The carrier protein, in its new configuration, has a decreased affinity for potassium, and the two ions move into the cytoplasm. The protein now has a higher affinity for sodium ions, and the process starts again.

Several things have happened as a result of this process. At this point, there are more sodium ions outside the cell than inside and more potassium ions inside than out. For every three sodium ions that move out, two potassium ions move in. This results in the interior being slightly more negative relative to the exterior. This difference in charge is important in creating the conditions necessary for the secondary process. The sodium-potassium pump is, therefore, an electrogenic pump (a pump that creates a charge imbalance), creating an electrical imbalance across the membrane and contributing to the membrane potential.

Secondary Active Transport (Co-transport)

Secondary active transport uses the kinetic energy of the sodium ions to bring other compounds, against their concentration gradient into the cell. As sodium ion concentrations build outside of the plasma membrane because of the primary active transport process, this creates an electrochemical gradient. If a channel protein exists and is open, the sodium ions will move down its concentration gradient across the membrane. This movement transports other substances that must be attached to the same transport protein in order for the sodium ions to move across the membrane (Figure 5.20). Many amino acids, as well as glucose, enter a cell this way. This secondary process also stores high-energy hydrogen ions in the mitochondria of plant and animal cells in order to produce ATP. The potential energy that accumulates in the stored hydrogen ions translates into kinetic energy as the ions surge through the channel protein ATP synthase, and that energy then converts ADP into ATP.