9 Carbon & Functional Groups

Jung Choi; Mary Ann Clark; and Matthew Douglas

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Explain why carbon is important for life

- Describe the role of functional groups in biological molecules

Many complex molecules called macromolecules, such as proteins, nucleic acids (RNA and DNA), carbohydrates, and lipids comprise cells. The macromolecules are a subset of organic molecules (carbon-containing molecules) that are especially important for life. The fundamental component for all of these macromolecules is carbon. The carbon atom has unique properties that allow it to form covalent bonds to as many as four different atoms, making this versatile element ideal to serve as the basic structural component, or “backbone,” of the macromolecules.

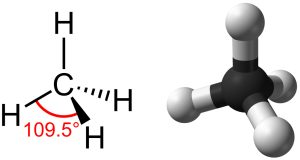

Individual carbon atoms have an incomplete outermost electron shell. With an atomic number of 6 (six electrons and six protons), the first two electrons fill the inner shell, leaving four in the second shell. Therefore, carbon atoms can form up to four covalent bonds with other atoms to satisfy the octet rule. The methane molecule provides an example: it has the chemical formula CH4. Each of its four hydrogen atoms forms a single covalent bond with the carbon atom by sharing a pair of electrons. This results in a filled outermost shell.

Hydrocarbons

Hydrocarbons are organic molecules consisting entirely of carbon and hydrogen, such as methane (CH4) described above. We often use hydrocarbons in our daily lives as fuels—like the propane in a gas grill or the butane in a lighter. The many covalent bonds between the atoms in hydrocarbons store a great amount of energy, which releases when these molecules burn (oxidize). Methane, an excellent fuel, is the simplest hydrocarbon molecule, with a central carbon atom bonded to four different hydrogen atoms, as Figure 2.21 illustrates. The shape of its electron orbitals determines the shape of the methane molecule’s geometry, where the atoms reside in three dimensions.

As the backbone of the large molecules of living things, hydrocarbons may exist as linear carbon chains, carbon rings, or combinations of both. Furthermore, individual carbon-to-carbon bonds may be single, double, or triple covalent bonds, and each type of bond affects the molecule’s geometry in a specific way. This three-dimensional shape or conformation of the large molecules of life (macromolecules) is critical to how they function.

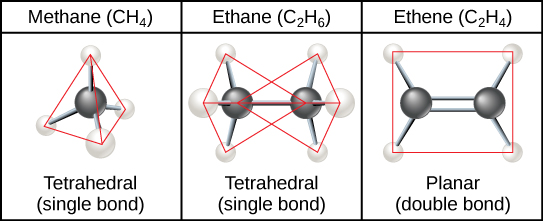

Hydrocarbon Chains

Successive bonds between carbon atoms form hydrocarbon chains. These may be branched or unbranched. Furthermore, a molecule’s different geometries of single, double, and triple covalent bonds alter the overall molecule’s geometry, as Figure 2.22 illustrates. The hydrocarbons ethane, ethene, and ethyne serve as examples of how different carbon-to-carbon bonds affect the molecule’s geometry. The names of all three molecules start with the prefix “eth-,” which is the prefix for two carbon hydrocarbons. The suffixes “-ane,” “-ene,” and “-yne” refer to the presence of single, double, or triple carbon-carbon bonds, respectively. Thus, propane, propene, and propyne follow the same pattern with three carbon molecules, butane, butene, and butyne for four carbon molecules, and so on. Double and triple bonds change the molecule’s geometry: single bonds allow rotation along the bond’s axis, whereas double bonds lead to a planar configuration and triple bonds to a linear one. These geometries have a significant impact on the shape a particular molecule can assume.

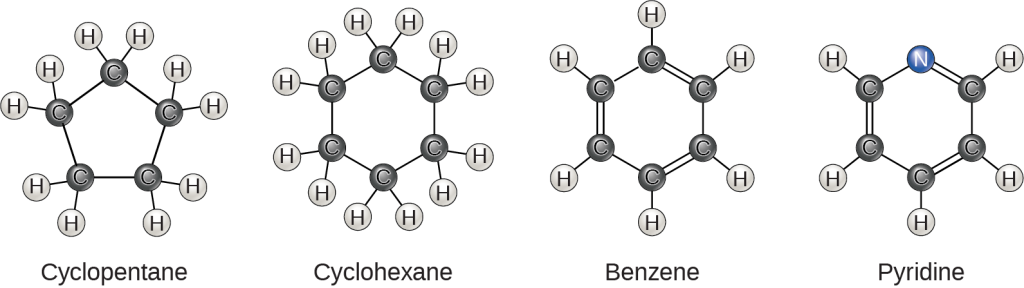

Hydrocarbon Rings

So far, the hydrocarbons we have discussed have been aliphatic hydrocarbons. Another special type of hydrocarbon, the aromatic hydrocarbon, consists of closed rings of carbon atoms with alternating single and double bonds. We also find ring structures in aliphatic hydrocarbons, which we can see by comparing cyclohexane’s structure to benzene in Figure 2.23. Examples of biological molecules that incorporate the benzene ring include some amino acids and cholesterol and its derivatives, including the hormones estrogen and testosterone. We also find the benzene ring in the herbicide 2,4-D. Benzene is a natural component of crude oil and has been classified as a carcinogen. Some hydrocarbons have both aliphatic and aromatic portions. Beta-carotene is an example of such a hydrocarbon.

Isomers

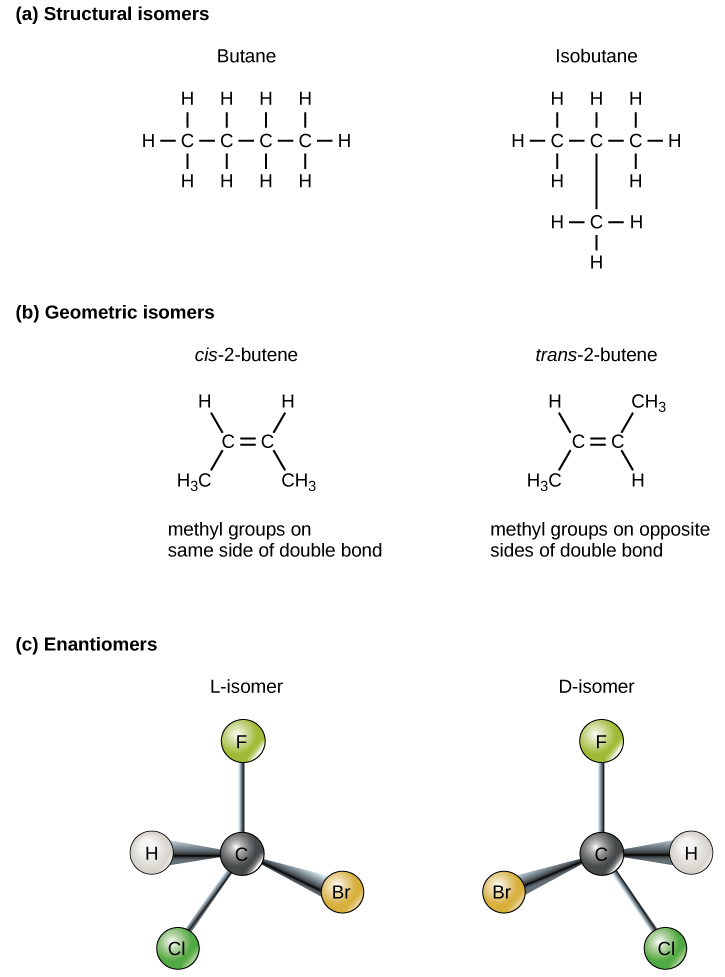

The three-dimensional placement of atoms and chemical bonds within organic molecules is central to understanding their chemistry. We call molecules that share the same chemical formula but differ in the placement (structure) of their atoms and/or chemical bonds isomers. Structural isomers (like butane and isobutane in Figure 2.24a) differ in the placement of their covalent bonds: both molecules have four carbons and ten hydrogens (C4H10), but the different atom arrangement within the molecules leads to differences in their chemical properties. For example, butane is suited for use as a fuel for cigarette lighters and torches, whereas isobutane is suited for use as a refrigerant and a propellant in spray cans.

Geometric isomers, alternatively, have similar placements of their covalent bonds but differ in how these bonds are made to the surrounding atoms, especially in carbon-to-carbon double bonds. In the simple molecule butene (C4H8), the two methyl groups (CH3) can be on either side of the double covalent bond central to the molecule, as Figure 2.24b illustrates. When the carbons are bound on the same side of the double bond, this is the cis configuration. If they are on opposite sides of the double bond, it is a trans configuration. In the trans configuration, the carbons form a more or less linear structure, whereas the carbons in the cis configuration make a bend (change in direction) of the carbon backbone.

Visual Connection

Which of the following statements is false?

- Molecules with the formulas CH3CH2COOH and C3H6O2 could be structural isomers.

- Molecules must have a double bond to be cis–trans isomers.

- To be enantiomers, a molecule must have at least three different atoms or groups connected to a central carbon.

- To be enantiomers, a molecule must have at least four different atoms or groups connected to a central carbon.

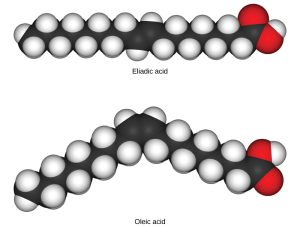

In triglycerides (fats and oils), long carbon chains known as fatty acids may contain double bonds, which can be in either the cis or trans configuration, as Figure 2.25 illustrates. Fats with at least one double bond between carbon atoms are unsaturated fats. When some of these bonds are in the cis configuration, the resulting bend in the chain’s carbon backbone means that triglyceride molecules cannot pack tightly, so they remain liquid (oil) at room temperature. Alternatively, triglycerides with trans double bonds (popularly called trans fats) have relatively linear fatty acids that are able to pack tightly together at room temperature and form solid fats. In the human diet, trans fats are linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, so many food manufacturers have reduced or eliminated their use in recent years. Polyunsaturated fats contain more than one double bond. In contrast to unsaturated fats, we call triglycerides without double bonds between carbon atoms saturated fats, meaning that they contain all the hydrogen atoms that a carbon chain of their length possibly could. Saturated fats are a solid at room temperature and usually of animal origin.

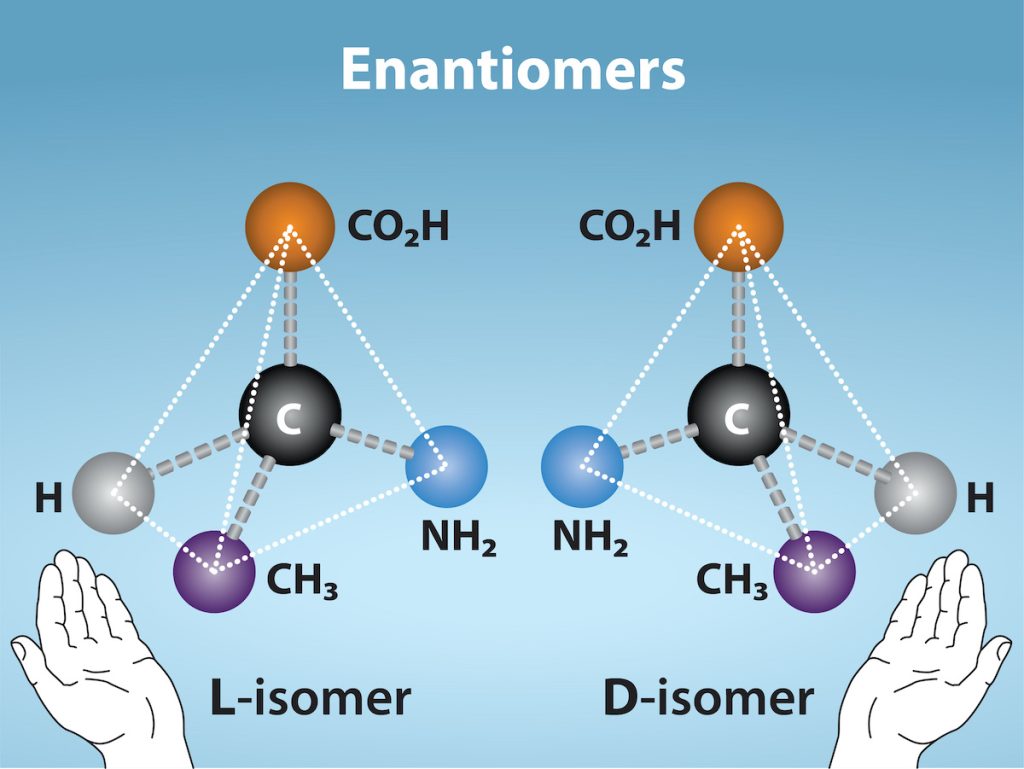

Enantiomers

Enantiomers are molecules that share the same chemical structure and chemical bonds but differ in the three-dimensional placement of atoms so that they are non-superimposable mirror images. Figure 2.26 shows an amino acid alanine example, where the two structures are nonsuperimposable. In nature, the L-forms of amino acids are predominant in proteins. Some D forms of amino acids are seen in the cell walls of bacteria and polypeptides in other organisms. Similarly, the D-form of glucose is the main product of photosynthesis and we rarely see the molecule’s L-form in nature.

Functional Groups

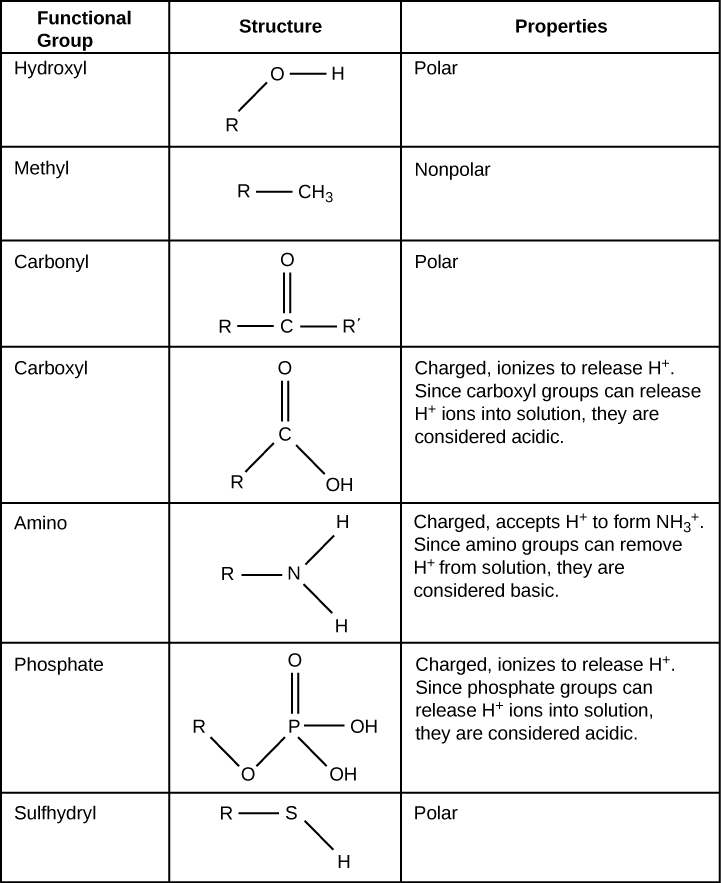

Functional groups are groups of atoms that occur within molecules and confer specific chemical properties to those molecules. We find them along the “carbon backbone” of macromolecules. Chains and/or rings of carbon atoms with the occasional substitution of an element such as nitrogen or oxygen form this carbon backbone. Molecules with such other elements in their carbon backbone are substituted hydrocarbons.

The functional groups in a macromolecule are usually attached to the carbon backbone at one or several different places along its chain and/or ring structure. Each of the four types of macromolecules—proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids—has its own characteristic set of functional groups that contributes greatly to its differing chemical properties and its function in living organisms.

A functional group can participate in specific chemical reactions. Figure 2.27 shows some of the important functional groups in biological molecules. They include: hydroxyl, methyl, carbonyl, carboxyl, amino, phosphate, and sulfhydryl. These groups play an important role in forming molecules like DNA, proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids. We usually classify functional groups as hydrophobic or hydrophilic depending on their charge or polarity characteristics. An example of a hydrophobic group is the nonpolar methyl molecule. Among the hydrophilic functional groups is the carboxyl group in amino acids, some amino acid side chains, and the fatty acids that form triglycerides and phospholipids. This carboxyl group ionizes to release hydrogen ions (H+) from the COOH group, resulting in the negatively charged COO– group. This contributes to the hydrophilic nature of whatever molecule bears it. Other functional groups, such as the carbonyl group, have a partially negatively charged oxygen atom that may form hydrogen bonds with water molecules, again making the molecule more hydrophilic.

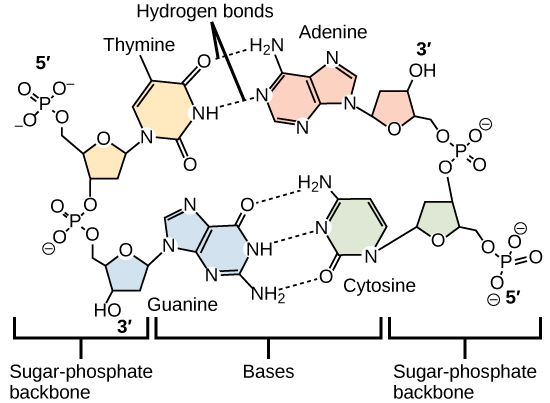

Hydrogen bonds between functional groups (within the same molecule or between different molecules) are important to the function of many macromolecules and help them to fold properly into and maintain the appropriate shape for functioning. Hydrogen bonds are also involved in various recognition processes, such as DNA complementary base pairing and the binding of an enzyme to its substrate, as Figure 2.28 illustrates.