4 Chapter 4: Technology and Ethics

Shariq I. Sherwani, PhD, MBA and Robert D. Hall, PhD

Introduction

In our modern world, it may seem like ancient history to have had access to mobile devices, color- and hi-definition televisions, laptops, and social media networking sites (SNS). Yet, in the scale of human history, the world of modern technology and the internet is still relatively young. Since the Internet’s creation in 1969, public access to the Internet and the creation of the World Wide Web (www) in 1991, and the proliferation of internet service providers through the late 1990s, the technology that shapes your life today and tomorrow is still relatively new. In this chapter, we will review what we call computer-mediated communication (CMC) and key findings of CMC applied to interpersonal communication. We will then transition into a discussion on communication ethics given technology’s and the internet’s ever evolving landscape of what could be considered ethical or unethical. To get started, it’s essential to understand the evolution of CMC.

4.1 History of CMC

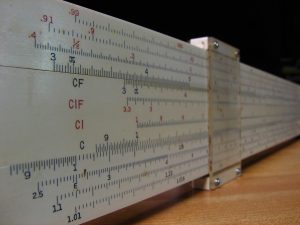

So, our first question should be, “What is a computer?” In its earliest use, “computers” were people who performed massive amounts of calculations by hand or using a tool like an abacus (Image 1) or slide rule (Image 2). As you can imagine, this process wasn’t exactly efficient and took a lot of human resources. Today, it would seem inhumane that the word “computer” would refer to a person. The 2016 movie Hidden Figures shows the true story of a group of African American computers who created the calculations to land the first astronaut on the moon. The first mechanical ancestor of the computer we have today was created in 1801 by a Frenchman named Joseph Marie Jacquard, who created a loom that used punched wooden cards to weave fabric. The idea of “punch cards” would be the basis of many generations of computers until the 1960s. The 1970s saw the start of the explosion of the personal computer. In 1981, IBM released the Acorn, which runs on Microsoft DOS, which is followed up by Apple’s Lisa in 1983, which had a graphic user interface. With the onset of the personal computer, technology has come a long way in enabling these personal devices to interact with one another.

Image 1. “Abacus” by blaahhi is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Image 2. “Slide Rule” by Roger Smith is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

With each new computer development, we’ve seen new technologies emerge that have helped us communicate and interact. One significant development in 1969 changed the direction of humanity forever. Starting in 1965, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology were able to get two computers to “talk” to each other. Of course, it’s one thing to get two computers side-by-side to talk to each other, but could they get computers at a distance to talk to each other (in a manner similar to how people use telephones to communicate at a distance)?

Researchers at both UCLA and Stanford, with grant funding from the U.S. Defense Department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), set out to attempt having computers at a distance to talk to each other. In 1969, UCLA student Charley Kline attempted the first computer-to-computer communication over a distance from his terminal in Los Angeles to a terminal at Stanford. The first message to be sent was to be a simple one, “login.” The letter “l” was sent, then the letter “o,” and then the system crashed. So, the first message ever sent over what would become the Internet was “lo.” An hour later, Kline got the system up and running again, and the full word “login” was sent.

In addition to email, another breakthrough in computer-mediated communication was the development of Internet forums or message/bulletin boards, which were online discussion sites where people can hold conversations in the form of posted messages. Steve Walker created an early message system for ARPANET. The primary message list for professionals was MsgGroup. The number one unofficial message list was SF-Lovers, a science fiction list. As you can see, from the earliest days of the Internet, people were using the Internet as a tool to communicate and interact with people who had similar interests.

4.2 Asynchronous and Synchronous Communication

For our part, these technologies are what we call asynchronous, or communication in which the sender and receiver are not concurrently engaged in communication. When Person A sends a message, Person B did not need to be present at the same time to receive the message. There could be a delay of hours or even days before that message received and Person B responded. In the case of e-mails and early mediated communication, asynchronous messages were akin to letter writing. As the Internet grew and speed and infrastructure became more established, the development of synchronous technology develops, or a form of communication in which the sender and receiver are concurrently engaged in communication. When Person A sends a message, Person B is receiving that message in real-time like they would in a face-to-face (FtF) interaction. In this case, synchronous messages are akin to talking to someone on the telephone, which in and of itself is a type of mediated communication.

Nonverbal Cues

One early realization about email and message boards is that people relied solely on text to interpret a message with no form of nonverbal communication attached. While we will more explicitly discuss nonverbal communication in Chapter 7 of this text, one of the key concerns of CMC researchers is that of nonverbal cues. As we will discuss in Chapter 7 in this text, so much of how we understand each other is based on our nonverbal behaviors, and emoticons, or emotion icons, were an attempt to bring a lost part of the human communicative experience to a text-based communicative experience. We should be aware that people form impressions of us based not just on what we post on our profiles but also on our friends and the content that they post on our profiles. In short, as in our offline lives, we are judged online by the information we post, the emoticons we use, the things we like, and the company we keep (Walther et al., 2008). So, let’s take a look at the important considerations of nonverbal cues in CMC.

First, CMC interactions “filter out” communicative cues found in FtF interactions (Culnan & Markus, 1987). For example, if you’re on the telephone with someone, you can’t see their eye contact, gestures, facial expressions, etc. If you’re reading an email, you have no nonverbal information to help you interpret the message because there is none. That’s what is meant by nonverbal cues that have been filtered out. Unfortunately, even if we don’t have the nonverbal cues to help us interpret a message, we interpret the message using our perceptions of how the sender intended us to understand this message, which is often wrong.

Image 3. “Emojis Minimalistas” by tobiaschames is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

While some websites may have spelled-out rules for interacting on their platform, often referred to as Terms of Service, there are also norms for how people communicate. A norm, in this context, is an accepted standard for how one communicates and interacts with others in a communicative environment. For example, one norm that can really frustrate people in text-based CMC environments is yelling, or TYPING IN ALL CAPITAL LETTERS. Despite the fact that users often create ways to make up for filtered-out cues, it is still possible to form and maintain important interpersonal relationships via CMC. Thus, we will next discuss social information processing theory.

4.3 Social Information Processing Theory

The first truly unique theory designed to look at CMC from a communication perspective came from Joseph Walther back in 1992 in his social information processing theory. As someone with a background in communication, Walther realized that interpersonal interactions change over time. As such, some of the other communication theories really didn’t take into account how interpersonal relationships evolve as the interpersonal interactants spend more time getting to know one another. Other CMC theories (e.g., media richness theory, Lengel, 1983) tend to focus on the filtered-out nonverbal aspects of CMC and assume that because of the lack of nonverbal cues in CMC, people will inherently find CMC as either less rich or less present when compared to FtF interactions. Walther (1992), however, argued that the filtering out of nonverbal cues doesn’t hurt an individual’s ability to form an impression of someone over time in a CMC context. Ultimately, Walther argues that relationships formed in a CMC context can develop like those that are FtF over time. He does admit that these relationships will take more time to develop, but that they can reach the same end states as those relationships formed FtF.

Walther (1996) later expanded his ideas of social information processing to include a new concept he dubbed hyperpersonal interactions. Hyperpersonal interactions are those that exceed those possible of traditional FtF interactions. For example, many people who belong to online self-help groups discuss feelings and ideas that they would never dream of discussing with people in an FtF interaction unless that person was their therapist (Moya et al., 2008). Furthermore, during CMC interactions an individual can refine her or his message in a manner that is impossible to do during an FtF interaction, which will help present a specific face to an interactant (Walther, 2007). I’m sure we’ve all written a text, Facebook post, or email and then decided to delete what you’d just written because it was in your best interest not to put it out to the world. In CMC interactions, we have this ability to fine-tune our messages before transmitting; whereas, in FtF messages, once something has been communicated, there is no ability to refine the message. Furthermore, in FtF interactions, there is an expectation that the interaction keeps moving at a steady pace without the ability to edit one’s ideas; whereas, with CMC we can take time to fine-tune our messages in a way that is impossible during an FtF interaction.

In acknowledging that we can create important and lasting impressions and relationships through CMC, it is imperative for us to consider how to interact ethically via CMC. Thus, we will next discuss a key concept in developing our online presence and professionalism: netiquette.

4.4 Netiquette

Over the years, numerous norms have been created to help individuals communicate in the CMC context, and they’re so common that we have a term for them, netiquette. Netiquette is the set of professional and social rules and norms that are considered acceptable and polite when interacting with another person(s) through mediated technologies. Let’s breakdown this definition.

Contexts

First, the definition emphasizes that different contexts can create different netiquette needs. Specifically, how one communicates professionally and how one communicates socially are often quite different. For example, you may find it entirely appropriate to say, “What’s up?!” at the beginning of an email to a friend, but you would not find it appropriate to start an email to your boss in this same fashion. Furthermore, it may be entirely appropriate to downplay or not worry about spelling errors or grammatical problems in a text you send to a friend, but it is completely inappropriate to have those same errors and problems in a text sent to a professional-client or coworker.

This lack of professionalism is also a problem commonly discussed by college and university faculty and staff. Think about the last email you sent to one of your professors. Was this email professional? Did you remember to sign your name? We mention this because the context is different from your day-to-day use of email. Here are some general guidelines for sending professional emails:

“Netiquette Reminders” by doreen.gailo is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

- Include a concise, direct subject line.

- Do not mark something as “urgent” unless it really is.

- Have a proper greeting (Dear Dr. W, Mr./Mrs./Ms. X, Professor Y:, etc.)

- Double-check your grammar.

- Correct any spelling mistakes.

- Include only essential information.

- Your message should be concise.

- Make your intention known clearly and directly.

- Make sure your message follows a logical organization.

- Be polite and ensure your tone is appropriate.

- Avoid all CAPS or all lowercase letters.

- Avoid “textspeak” (e.g., plz, lol, etc.).

- If you want the recipient to do something, make the desired action very clear.

- Have a clear closing (using “please” and “thank you”).

- Do not send an email if you’re angry or upset.

- Edit and proofread before hitting “send.”

- Use “Reply All” selectively (very selectively).

Rules & Norms

Second in the definition of netiquette, netiquette is a combination of both rules and norms. Part of being a competent communicator in a CMC environment is knowing what the rules are. For example, if you know that the rules ban hate speech on an SNS, then engaging in hate speech using that platform shows a disregard for the rules and would not be considered appropriate behavior. In essence, hate speech is anti-netiquette. We also do not want to ignore the fact that norms often develop in different CMC contexts. For example, maybe you’re taking an online course and you’re required to engage in weekly discussions. One common norm in an online class is to check the previously replies to a post before posting your reply. If you don’t, then it’s like jumping into a conversation that’s already occurred and throwing your two-cents in without knowing what’s happening.

Acceptable & Polite CMC Behavior

Third, we believe that netiquette attempts to govern what is both acceptable and polite. Yelling via a text message may be acceptable to some of your friends, but is it polite given that typing in all caps is generally seen as yelling? Being polite is merely showing others respect and demonstrating socially appropriate behaviors.

Mindfulness Activity

If you’ve spent any time online recently, you may have noticed that it can definitely feel like a cesspool. There are so many trolls that are making the Internet a place where genuine interactions are hard to come by. Abblett (2019) came up with five specific guidelines for interacting with others online:

- Be kind and compassionately courteous with all posts and comments.

- No hate speech, bullying, derogatory or biased comments regarding self, others in the community, or others in general.

- No Promotions or Spam.

- Do not give out mental health advice.

- Respect everyone’s privacy and be thoughtful in the nature and depth of one’s sharing .

Think about your interactions with others in the online world. Have you ever communicated with others without considering attention, intention, and attitude?

Online Interaction

Fourth, the definition of netiquette involves interacting with others. Now, this interaction can be one-on-one or one-to-many. The first category, one-on-one, is more in the wheelhouse for interpersonal communication. Examples of one-on-one CMC could include sending a text to one person, sending an email to one person, talking to one person via Zoom, etc. One-to-many is also a possibility and will require its own sets of rules and norms. Some common examples of one-to-many CMC could include engaging in a group chat via texting, “replying all” to an email received, being interviewed by a committee via Zoom, etc. Notice that our examples for one-to-many involve the same technologies used for one-on-one communication. With one-to-many, we’re dealing with a larger number of people involved in the communicative interactions.

Range of Mediated Technologies

Lastly, netiquette can vary based on the different types of mediated technologies. For example, it may be considered entirely appropriate for you to scream, yell, and curse when your playing with your best friend on Fortnite, but it wouldn’t be appropriate using the same communicative behaviors when engaging in a video conference over Zoom. Both technologies use Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) to some extent, but the platforms and the contexts are very different, so they call for different types of communicative behaviors. Some differences will exist in netiquette based on whether you’re in an entirely text-based medium (e.g., email, texting, etc.) or one where people can see you (e.g., Zoom, Teams, etc.).

Ultimately, engaging in netiquette requires you to learn what is considered acceptable and polite behavior across a range of different technologies. With each medium, then, we must consider how to act ethically. Thus, we will now turn to a discussion on communication ethics.

Communication Has Ethical Implications

Another culturally and situationally relative principle of communication is the fact that communication has ethical implications. Communication ethics deals with the process of negotiating and reflecting on our actions and communication regarding what we believe to be right and wrong. Aristotle said, “In the arena of human life the honors and rewards fall to those who show their good qualities in action.” Judy C. Pearson, Jeffrey T. Child, Jody L. Mattern, and David H. Kahl Jr., “What Are Students Being Taught about Ethics in Public Speaking Textbooks?” Communication Quarterly 54, no. 4 (2006): 508. Aristotle focuses on actions, which is an important part of communication ethics. While ethics has been studied as a part of philosophy since the time of Aristotle, only more recently has it become applied. In communication ethics, we are more concerned with the decisions people make about what is right and wrong than the systems, philosophies, or religions that inform those decisions. Much of ethics is gray area. Although we talk about making decisions in terms of what is right and what is wrong, the choice is rarely that simple. Aristotle goes on to say that we should act “to the right extent, at the right time, with the right motive, and in the right way,” a quote which connects to communication competence, which focuses on communicating effectively and appropriately.

Communication has broad ethical implications. Later in this book we will discuss the importance of ethical listening, how to avoid plagiarism, how to present evidence ethically, and how to apply ethical standards to mass media and social media. These are just a few examples of how communication and ethics will be discussed in this book, but hopefully you can already see that communication ethics is integrated into academic, professional, personal, and civic contexts.

When dealing with communication ethics, it’s difficult to state that something is 100 percent ethical or unethical. I tell my students that we all make choices daily that are more ethical or less ethical, and we may confidently decide only later to learn that it was not the most ethical option. In such cases, our ethics and goodwill are tested, since in any given situation multiple options may seem appropriate, but we can only choose one. If, in a situation, we decide and we reflect on it and realize we could have made a more ethical choice, does that make us a bad person? While many behaviors can be more easily labeled as ethical or unethical, communication isn’t always as clear. Murdering someone is generally thought of as unethical and illegal, but many instances of hurtful speech, or even what some would consider hate speech, have been protected as free speech. This shows the complicated relationship between protected speech, ethical speech, and the law. In some cases, people see it as their ethical duty to communicate information that they feel is in the public’s best interest. The people behind WikiLeaks, for example, have released thousands of classified documents related to wars, intelligence gathering, and diplomatic communication. WikiLeaks claims that exposing this information keeps politicians and leaders accountable and keeps the public informed, but government officials claim the release of the information should be considered a criminal act. Both parties consider the other’s communication unethical and their own communication ethical. Who is right?

Since many of the choices we make when it comes to ethics are situational, contextual, and personal, various professional fields have developed codes of ethics to help guide members through areas that might otherwise be gray or uncertain. Doctors take an oath (Hippocratic Oath) to do no harm to their patients, and journalists follow ethical guidelines that promote objectivity and provide for the protection of sources. Although businesses and corporations have gotten much attention for high-profile cases of unethical behavior, business ethics has become an important part of the curriculum in many business schools, and more companies are adopting ethical guidelines for their employees.

National Communication Association Credo for Ethical Communication

Throughout your life journey, you will be challenged to think critically about a variety of communication issues, and many of those issues will involve questions of ethics. Therefore, it is important that we have a shared understanding of ethical standards for communication. I tell my students that I consider them communication scholars while they are in my class, and we always take a class period to learn about ethics using the National Communication Association’s (NCA) “Credo for Ethical Communication,” since the NCA is the professional organization that represents communication scholars and practitioners in the United States.

We all have to consider and sometimes struggle with questions of right and wrong. Since communication is central to the creation of our relationships and communities, ethical communication should be a priority of every person who wants to make a positive contribution to society. The NCA’s “Credo for Ethical Communication” reminds us that communication ethics is relevant across contexts and applies to every channel of communication, including media. National Communication Association, “NCA Credo for Ethical Communication,” accessed May 18, 2012,http://natcom.org/Tertiary.aspx?id=2119&terms=ethical %20credo. The credo goes on to say that human worth and dignity are fostered through ethical communication practices such as truthfulness, fairness, integrity, and respect for self and others. The emphasis in the credo and in the study of communication ethics is on practices and actions rather than thoughts and philosophies. Many people claim high ethical standards but do not live up to them in practice. While the credo advocates for, endorses, and promotes certain ideals, it is up to each one of us to put them into practice. We all have been witness to unethical communication at one point in our lives or another. We may have even contributed to such communication. What drives such behavior? What are some examples of unethical communication that you have witnessed? Read through the whole credo. Of the nine principles listed, which do you think is most important and why? The following are the nine principles stated in the credo. The credo can be accessed at the following link http://natcom.org/Tertiary.aspx?id=2…thical%20credo.

- We advocate truthfulness, accuracy, honesty, and reason as essential to the integrity of

communication. - We endorse freedom of expression, diversity of perspective, and acknowledgement of dissent to

achieve the informed and responsible decision-making fundamental to civil society. - We strive to understand and respect other communicators’ intent before evaluating and

responding to their messages. - We promote access to communication resources and opportunities necessary to fulfill human

potential and contribute to the well-being of individuals, families, communities, and societies. - We promote a supportive climate of communication that entails caring, mutual understanding

and respect for individual communicators’ needs and characteristics. - We condemn communication that degrades individuals and humanity through distortion,

intimidation, coercion, and violence, and through the expression of intolerance and hatred. - We commit to supporting the courageous expression of personal convictions in pursuit of

fairness and justice. - We advocate sharing information, opinions, and feelings when facing significant decisions, while

also respecting privacy and confidentiality. - We accept responsibility for the short- and long-term consequences of our own communication

and expect the same from others

Key Takeaways

- Getting integrated: Increasing your knowledge of communication and improving your communication skills can positively affect your academic, professional, personal, and civic lives.

- In terms of academics, research shows that students who study communication and improve their communication skills are less likely to drop out of school and are more likely to have high grade point averages.

- Professionally, employers desire employees with good communication skills, and employees who have good listening skills are more likely to get promoted.

- Personally, communication skills help us maintain satisfying relationships.

- Communication helps us with civic engagement and allows us to participate in and contribute to our communities.

- Communication meets our physical needs by helping us maintain physical and psychological well-being; our instrumental needs by helping us achieve short- and long-term goals; our relational needs by helping us initiate, maintain, and terminate relationships; and our identity needs by allowing us to present ourselves to others in particular ways.

- Communication is a process that includes messages that vary in terms of conscious thought and intention. Communication is also irreversible and unrepeatable.

- Communication is guided by culture and context.

- We learn to communicate using systems that vary based on culture and language.

- Rules and norms influence the routines and rituals within our communication.

- Communication ethics varies by culture and context and involves the negotiation of and reflection on our actions regarding what we think is right and wrong.

Exercises

- Getting integrated: The concepts of integrative learning and communication ethics are introduced in this section. How do you see communication ethics playing a role in academic, professional, personal, and civic aspects of your life?

- Identify some physical, instrumental, relational, and identity needs that communication helps you meet in a given day.

- We learned in this section that communication is irreversible and unrepeatable. Identify a situation in which you wished you could reverse communication. Identify a situation in which you wished you could repeat communication. Even though it’s impossible to reverse or repeat communication, what lessons can be learned from these two situations you identified that you can apply to future communication?

- What types of phatic communion do you engage in? How are they connected to context and/or social rules and norms?

References

Abblett, M. (2019). 5 rules for sharing genuinely and safely online: No matter what kind of social community you find yourself in, it is important to abide by a few specific guidelines for safe sharing. Mindful. Retrieved from https://www.mindful.org/5-rules-for-sharing-genuinely-and-safely-online/

Culnan, M. J., & Markus, M. L. (1987). Information technologies. In F. M. Jablin, L. L. Putman, K. H. Roberts, and L. W. Porter (Eds.), Handbook of organizational communication: An interdisciplinary perspective (pp. 420-443). Sage

Lengel, R. H. (1983). Managerial information process and communication-media source selection behavior [Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation]. Texas A&M University.

Moya, M., Oliveros, J. A., Rentutar, D., Reyes, M. G., Sison, M. A. (2008). Up close and hyper-personal: The formation of hyper-personal relationships in online support groups. Plaridel Journal of Communication, Media, and Society, 5(1), 89-118. https://doi.org/10.52518/2008.5.1-05mmylvrsrnttrrysssn

Walther, J. B. (1992). Interpersonal effects in computer-mediated interaction: A relational perspective. Communication Research, 19(1), 52–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365092019001003

Walther, J. B. (1996). Computer-mediated communication: Impersonal, interpersonal, and hyperpersonal interaction. Communication Research, 23(1), 3-43. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365096023001001

Walther, J. B. (2007). Selective self-presentation in computer-mediated communication: Hyperpersonal dimensions of technology, language, and cognition. Computers in Human Behavior, 23(5), 2538-2557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2006.05.002

Walther, J. B., van der Heide, B., Kim, S. Y., Westerman, D., & Tong, S. T. (2008). The role of friends’ appearance and behavior on evaluations of individuals on Facebook: Are we known by the company we keep?. Human Communication Research, 34(1), 28-49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2007.00312.x

This chapter included sections of the following materials:

“Connecting and Relating: Why Interpersonal Communication Matters” licensed by Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

“Interpersonal Communication” licensed by CC BY 3.0.