7 Chapter 7 – Nonverbal Communication

James Stein, PhD

Introduction

Intuitively, most people understand that nonverbal communication matters. From the common reference to the eyes as “the window of the soul” to popstar Jesse McCartney famously declaring, ” I don’t speak Spanish, Japanese, or French, but the way your body’s talking definitely makes sense,” there are a bounty of ways in which we are reminded that meaning is communicated through more than just the spoken word. Lest we fall into a series of “well, no duh” moments, we will frame our discussion of nonverbal communication as less about what and more about why and how. Yes, of course nonverbal communication is meaningful – substantially more meaningful that verbal communication. But establishing that nonverbal communication matters is only part of the deal. Following our introductory section, the real work of understanding what nonverbal communication can look like in interpersonal interactions and what implications it can carry will matter much more. Let’s begin.

7.1 – Introducing Nonverbal Communication

Nonverbal communication is defined as communication that is produced by some means other than words (eye contact, body language, or vocal cues, for example; Ekman & Friesen, 1969). Rather than thinking of nonverbal communication as the opposite of, or as separate from, verbal communication, it’s more accurate to view them as operating side by side—as part of the same system. Yet, as part of the same system, they still have important differences, including how the brain processes them. For instance, nonverbal communication is typically governed by the right side of the brain and verbal, the left (Andersen, 1999). As such, the way that we craft, interpret, and normalize verbal and nonverbal communication differs dramatically. Let’s look at some of the ways in which nonverbal messaging is special.

Nonverbal Communication Conveys Important Emotional Messages

You’ve probably heard that more meaning is generated from nonverbal communication than from verbal. Some studies have claimed that 90 percent of our meaning is derived from nonverbal signals, but more recent and reliable findings claim that it is closer to 65 percent (Guerrero & Floyd, 2006). We may rely more on nonverbal signals in situations where verbal and nonverbal messages conflict and in situations where emotional or relational communication is taking place (Hargie, 2011). For example, the question “What are you doing tonight?” could mean any number of things, but we could rely on posture, tone of voice, and eye contact to see if the person is just curious, suspicious, or hinting that they would like company for the evening.

We also put more weight on nonverbal communication when determining a person’s credibility. If a classmate delivers a speech in class and her verbal content seems well-researched and unbiased, but her nonverbal communication is poor (her voice is monotone, she avoids eye contact, she fidgets), we may have reasonable (though technically unfounded) questions about her credibility. Conversely, in some situations, verbal communication might carry more meaning than nonverbal. When texting, for example, verbal communication likely accounts for most meaning generated. That is, unless you are a big emoji person. Moreover, the advent of stickers, audio/screen filters, and easy-to-access video editing services on apps like Snapchat and Tiktok can move the needle back in nonverbal communication’s favor. Importantly, these advents open the door for misunderstandings in a variety of ways. Such miscommunications are in need of explicit attention.

Nonverbal is Ambiguous

A particularly challenging aspect of nonverbal communication is the fact that it is ambiguous. Said differently, nonverbal communication can be a bit random. In the seventies, nonverbal communication as a topic was trendy. Some were under the impression that we could use nonverbal communication to “read others like a book.” One of the authors remembers her cousin’s wife telling her that she shouldn’t cross her arms because it signaled to others that she was closed off. It would be wonderful if crossing one’s arms signaled one meaning, but think about the many meanings of crossing one’s arms. An individual may have crossed arms because the individual is cold, upset, sad, or angry. It is impossible to know unless a conversation is paired with nonverbal behavior.

Another great example of ambiguous nonverbal behavior is flirting! Consider some very stereotypical behavior of flirting (e.g., smiling, laughing, a light touch on the arm, or prolonged eye contact). Each of these behaviors signals interest to others. The question is whether an individual engaging in these behaviors is indicating romantic interest or a desire for platonic friendship…and that can have some really embarrassing outcomes if acted on improperly.

Let’s not also forget the desire for people to fancy themselves human lie detectors. Ironically, lie detectors aren’t admissible in court anymore – and for good reason! A person’s heart rate, blood pressure, or sweat production increasing does not necessarily mean that they are lying! Sorry, to ruin the fun, but a person looking up and to the left is not giving away that they’re lying. Behaviors, in a vacuum, mean very little until appropriately contextualized. Thus, no one specific behavior can tell you for sure whether or not someone is lying.

Omnipresent

Nonverbal communication is omnipresent, as in, all around us at all times. Silence is an excellent example of nonverbal communication being omnipresent. Have you ever given someone the “silent treatment?” If so, you understand that by remaining silent, you are trying to convey some meaning, such as “You hurt me” or “I’m really upset with you.” Thus, silence makes nonverbal communication omnipresent.

Another way of considering the omnipresence of nonverbal communication is to consider the way we walk, posture, engage in facial expression, eye contact, lack of eye contact, gestures, etc. When sitting alone in the library working, your posture may be communicating something to others. If you need to focus and don’t want to invite communication, you may keep your head down and avoid eye contact. Suppose you are walking across campus at a brisk pace. What might your pace be communicating?

When discussing the omnipresence of nonverbal communication, it is necessary to discuss Paul Watzlawick’s assertion that humans cannot, not communicate. This assertion is the first axiom of his interactional view of communication. According to Watzlawick, humans are always communicating. As discussed in the “silent treatment” example and the posture and walking example, communication is found in everyday behaviors that are common to all humans. We might conclude that humans cannot escape communicating meaning.

Usually Trusted

Here’s a big problem, the combination of nonverbal communication’s omnipresence and ambiguity means that people are predisposed to 1) believe they’re great at interpreting nonverbal messages and 2) inherently trust nonverbal messages over their verbal counterparts. Communication scholars agree that the majority of meaning in any interaction is attributable to nonverbal communication. We have learned through research that the myth of “a lack of eye contact means someone is lying” is not necessarily true; but this myth does tell a story about how our culture views nonverbal communication. That view is simply that nonverbal communication is important and that it has meaning.

Another excellent example of nonverbal communication being trusted may be related to a scenario many have experienced. At times, children, adolescents, and teenagers will be required by their parents/guardians to say, “I’m sorry” to a sibling or the parent/guardian. Alternatively, you may have said “yes” to your parents/guardians, but your parent/guardian doesn’t believe you. A parent/guardian might say in either of these scenarios, “it wasn’t what you said, it was how you said it.” Thus, we find yet another example of nonverbal communication being the “go-to” for meaning in an interaction.

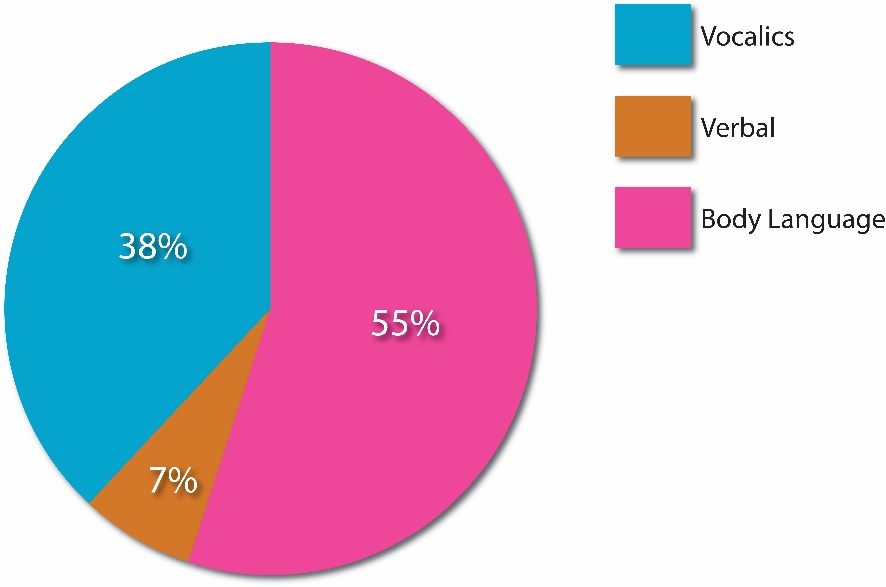

According to research, as much as 93% of meaning in any interaction is attributable to nonverbal communication. Albert Mehrabian (1971) asserts that this 93% of meaning can be broken into three parts: verbal communication, vocalics, and body language. Mehrabian’s work is widely reported and accepted. Other researchers Birdwhistell and Philpott say that meaning attributed to nonverbal communication in interactions ranges from 60 to 70% (Birdwhustell, 1970). Regardless of the actual percentage, it is worth noting that the majority of meaning in interaction is deduced from nonverbal communication.

Contradicting

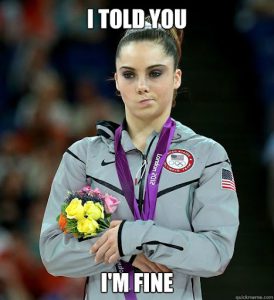

In 2012, Olympic gymnast McKayla Maroney was part of a gymnastics team that won the gold medal and also won a silver medal in the individual vault challenge. It was her reaction to winning this silver medal, however, that memeified her, and cemented her presence in internet lore. Importantly, McKayla’s expression of frustration, despite winning multiple olympic medals, became a beacon of verbal/nonverbal contradiction.

Figure 7.2 – McKayla Maroney’s iconic olympic facial display. Image curtesy of tumblr.com.

Consider a situation where a friend says, “The concert was amazing,” but the friend’s voice is monotone. A response might be, “oh, you sound real enthused.” Communication scholars refer to this as “contradicting” verbal and nonverbal behavior. When contradicting occurs, the verbal and nonverbal messages are incongruent. This incongruence heightens our awareness, and we tend to believe the nonverbal communication over verbal communication.

Can Lead to Misunderstandings

Comedian Samuel J. Comroe has tremendous expertise in explaining how nonverbal communication can be misunderstood. Comroe’s comedic routines focus on how Tourette’s syndrome affects his daily living. Tourette’s syndrome can change individual behavior, from uncontrolled body movements to uncontrolled vocalizations. Comroe often appears to be winking when he is not. He explains how his “wink” can cause others to believe he is joking when he isn’t. He also tells the story of how he met his wife in high school. During a skit, he played a criminal and she played a police officer. She told him to “freeze,” and he continued to move (due to Tourette’s). She misunderstood his movement to mean he was being defiant and thus “took him down.” You can watch Comroe’s routine here.

Although nonverbal misunderstandings can be humorous, these misunderstandings can affect interpersonal as well as professional relationships. One of the authors of this text once interviewed a candidate for a job opening at their university. During deliberations, the committee members noted that this particular candidate sounded “unenthusiastic” and “nervous,” primarily due to the lack of eye contact being made throughout the interview. The author reminded their committee members that a lack of eye contact and monotonic speech pattern may not be the result of a lack of enthusiasm, but instead the result of the candidate being on the autism spectrum. Thus the means and methods through which that candidate connects with others may look differently than more common nonverbal indicators.

As you continue to learn about nonverbal communication, consider how you come to understand nonverbal communication in interactions. Sometimes, the meaning of nonverbal communication can be fairly obvious. Most of the time a head nod in conversation means something positive such as agreement, “yes,” keep talking, etc. At other times, the meaning of nonverbal communication isn’t clear. Have you ever asked a friend, “did she sound rude to you” about a customer service representative? If so, you are familiar with the ambiguity of nonverbal communication.

7.2 – Channels of Nonverbal Communication

One important quality of nonverbal communication is that it is multifunctional. As such, there are dozens and dozens of channels through which nonverbal communication can be enacted. Thinking back to the earlier chapters, you’ll remember that a channel is simply the means through which a message is delivered. We’re going to cover some of the most well-known channels, and perhaps some of the more under-appreciated, but meaningful channels as well.

Physical Appearance

Although not one of the traditional categories of nonverbal communication, we really should discuss physical appearance as a nonverbal message. Whether we like it or not, our physical appearance has an impact on how people relate to us and view us. Someone’s physical appearance is often one of the first reasons people decide to interact with each other in the first place.

Let’s try an exercise. Whether you’re single or not, let’s pretend that you’re on the dating market and swiping through your favorite (or, perhaps, most tolerable) dating app. Would you consider swiping “yes” on a profile with a detailed, creative, and humorous description, but no profile picture? We’re guessing you wouldn’t. However, you might swipe right on a profile that features 3-4 very physically appealing pictures and no description whatsoever. Is that fair? No, but it does highlight the importance and primacy that we place on physical appearance.

Dany Ivy and Sean Wahl (2009) argue that physical appearance is a very important factor in nonverbal communication:

The connection between physical appearance and nonverbal communication needs to be made for two important reasons: (1) The decisions we make to maintain or alter our physical appearance reveal a great deal about who we are, and (2) the physical appearance of other people impacts our perception of them, how we communicate with them, how approachable they are, how attractive or unattractive they are, and so on.

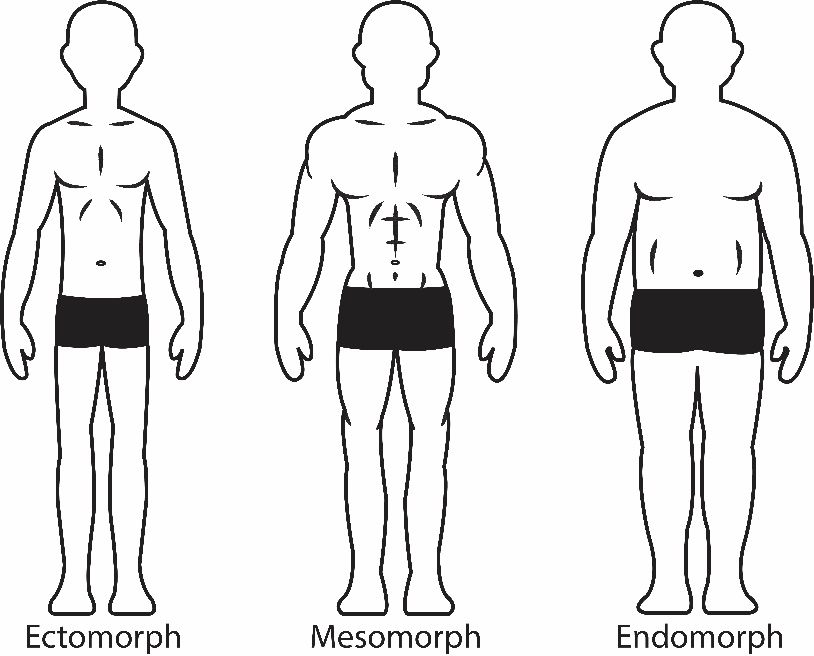

In fact, people ascribe all kinds of meanings based on their perceptions of how we physically appear to them. Everything from your height, skin tone, smile, weight, and hair (color, style, lack of, etc.) can communicate meanings to other people. To start our discussion, we’re going to look at the three somatotypes (aka body types; Sheldon, 1940).

Figure 7.3 Sheldon’s Somatotypes. Image taken from Sheldon, 1940.

Now, the Somatotyping Scale is based on the general traits that the three different somatotypes possess. Most people are more familiar with their physical looks. None of these body types are inherently better than the other, but their existence does raise a couple of meaningful points. First, knowing your Somatotype is important for producing the “best” version of yourself. Some folks are naturally a bit huskier (endomorphs), and would look gaunt and unhealthy if they tried to force themselves to look skinny. Others are naturally a bit more wiry (ectomorphs) and would therefor look silly if they tried to bulk up like their favorite gym influencer. Interestingly, and a reoccurring theme throughout the literature on physical attraction, is that people tend to view the more average body (i.e., mesomorphs) as the most attractive. This theme is referred to as koinophilia and it describes the tendency that humans have to gravitate toward the most common or ordinary looking people. As you consider your own body image, this can be a meaningful way to ground yourself and avoid the tendency to achieve aesthetic perfection.

Unfortunately, someone’s physical appearance has been shown to impact their lives in a number of different ways:

- Physically attractive students are viewed as more popular by their peers.

- Physically attractive people are seen as smarter.

- Physically attractive job applicants are more likely to get hired.

- Physically attractive people make more money.

- Physically attractive journalists are seen as more likable and credible.

- Physically attractive defendants in a court case were less likely to be convicted, and if they were convicted, the juries recommended less harsh sentences.

- Taller people are perceived as more credible.

- People who are overweight are less likely to get job interviews or promotions.

Now, this list is far from perfect and doesn’t necessarily take every possible scenario into account. Furthermore, there are some minor differences between females and males in how they perceive attraction and how they are influenced by attraction. Culture can also play a large part in how physical attractiveness impacts peoples’ perceptions. All this to reinforce that humans are not robots, we create and recreate our perceptions of attractiveness. What one person finds attractive another may find repulsive. So, yes, there are certain universal traits that most if not all people find attractive, but the individual and socio-cultural elements of attraction are equally worthy of consideration. Not to mention the fact that it’s not only about how you look, it’s about how you act! A physically attractive body isn’t worth much if the person operating that body doesn’t know how to use it! For that reason, we must next cover kinesics.

Kinesics refers to the study of hand, arm, body, and facial movements. And boy is it widely studied. In fact, many universities have entire kinesiology departments. It’s widely studied and applied in sports, as the mechanics of a jump shot, the swing of a bat, and throwing of a football, among other movements, greatly determine an athlete’s success on the field of play. We will look specifically at three different types of kinesics: facial expressions, eye behavior (oculesics) and gestures.

Facial Expressions. You may have heard the expression “a smile is worth a thousand words.” We have been smiling most of our lives, ever since the fourth week of life. These spontaneous smiles turn into smiles of genuine enjoyment known as Duchenne smiles. What is a Duchenne smile? According to the Paul Eckmann Group:

The Facial Action Coding System (FACS) research has shown that in a true enjoyment smile, the skin above and below the eye is pulled in towards the eyeball, and this makes for the following changes in appearance: the cheeks are pulled up; the skin below the eye may bag or bulge; the lower eyelid moves up; crows feet wrinkles may appear at the outer corner of the eye socket; the skin above the eye is pulled slightly down and inwards; and the eyebrows move down very slightly. A non-enjoyment smile, in contrast, features the same movement of the lip corners as the enjoyment smile but does not involve the changes due to the muscles around the eyes.

Figure 7.3 – A “Duchenne” or genuine smile. Image curtsey of tumblr.com.

A little story regarding these emotions. When Drs. Ekman and Freisen were collecting their data over 50 years ago, they first believed that there were just six universal displays. Like any good scholar, the two double checked their work and indeed found that contempt, that final expression in the above figure, is also universal. Contempt (feelings that you are superior to another or that they are beneath you) is distinguished by the simple act of pulling one corner of the mouth upward. Simple, but deadly. Consider the colloquialism of someone having a “punchable face.” No figure in modern pop culture exemplifies this expression more than Martin Shkrely, aka the “pharma bro.”

Figure 7.5. – Martin Shkrely exemplifying the expression of contempt. Image curtesy of tumblr.com.

Martin’s constant looks of contempt while being questioned about his motives for raising aids medication 50,000% (that’s 500x) overnight made him a viral sensation back in 2015. And it wasn’t because of his price gouging, it was because of his face.

While these universal facial expressions were recognized across cultural groups, research also showed that there were distinct differences in how each culture interprets and displays these emotions (Andersen, 1999). These became known as cultural display rules. Cultural display rules are intrinsically held within a culture’s norms and standards of behaviors. They help to govern the types and frequencies of acceptable emotions (Tsai, 2021). Different cultures have different structures of behavior and, therefore, different rules regarding how they display their emotions. This is especially true when it comes to eye contact, which we’ll dive into next.

Oculesics. It should come as no surprise that humans send messages through eye behaviors, primarily eye contact. While eye behaviors are often studied under the category of kinesics, they have their own branch of nonverbal studies called oculesics, which comes from the Latin word oculus, meaning “eye.” The face and eyes are the main point of focus during communication, and along with our ears, our eyes take in most of the communicative information around us. That saying of the eyes being the window to the soul is actually accurate in terms of where people typically think others are “located,” which is right behind the eyes (Spielman et al., 2014). Certain eye behaviors have become tied to personality traits or emotional states, as illustrated in phrases like “hungry eyes,” “evil eyes,” and “bedroom eyes.” To better understand oculesics, we will discuss the characteristics and functions of eye contact and pupil dilation.

Eye contact serves several communicative functions ranging from regulating interaction to monitoring interaction, to conveying information, to establishing interpersonal connections. In terms of regulating communication, we use eye contact to signal to others that we are ready to speak or we use it to cue others to speak. I’m sure we’ve all been in that awkward situation where a teacher asks a question, no one else offers a response, and he or she looks directly at us as if to say, “What do you think?” In that case, the teacher’s eye contact is used to cue us to respond. During an interaction, eye contact also changes as we shift from speaker to listener. US Americans typically shift eye contact while speaking— looking away from the listener and then looking back at his or her face every few seconds. Toward the end of our speaking turn, we make more direct eye contact with our listener to indicate that we are finishing up. While listening, we tend to make more sustained eye contact, not glancing away as regularly as we do while speaking (Martin & Nakayama, 2010).

Emblems are gestures that correspond to a word and an agreed-on meaning. Many gestures are emblems that have a verbal equivalent in a culture. Since emblems are culturally determined, you might run into instances of ambiguity or miscommunication. For example, in the United States the “everything is OK or good.” We might also do this by sticking our thumb, and only our thumb, straight up. That said, sticking a different finger straight up carries monumental meaning, though only in certain Western countries. If you were to ask us exactly which countries it’s okay to direct your middle finger toward someone without ramification, we might shrug, which is another example of an emblem.

While emblems can be used as direct substitutions for words, illustrators help emphasize or explain an idea. Think about a person who went fishing and then shows how big that fish that they caught was by extending their arms to show its size. “It was thiiiiisssss big” they declare confidently. Both that statement, and the nonverbal hand display mean nothing without the other. Thus, the nonverbal display illustrates and compliments the verbal message.

Affect displays show feelings and emotions. Consider how music and sports fans show enthusiasm. It is not uncommon to see people jumping up and down at sports events during a particularly exciting moment in a game. However, there are different norms depending on the sport. It would be inappropriate to demonstrate the same nonverbal gestures at a golf or tennis game as a football game.

Figure 7.6 – An expression of pure joy. Photo curtesy of flikr.com.

Affect displays are not always positive, of course. Affect itself is not a positive or negative word. Consider this adorable child who is, ironically, engaging in an emblematic affect display, signaling his displeasure without uttering a single word

Figure 7.7 – An example of “flipping the bird” as an emblematic affect display. Image curtesy of tumblr.com

Lastly, gestures that help coordinate the flow of conversation are called regulators. Raising your hand during class indicates that you want to say something. Even the Zoom videoconferencing platform uses a “raise hand” icon to help regulate communication during a session. Regulators often include head nods, eye contact or aversion and changes in posture. They are considered to be turn-taking cues in conversation. Individuals may sit back when listening but shift forward to indicate a desire to speak. Eye contact shifts frequently during a conversation to indicate listening or a desire to speak. Head nods are used as a sign of listening and often indicate that the speaker should continue speaking.

Those who study Vocalics focus not on the words that we choose, but the manner in which we say the words using our vocal cords. It includes the study of paralanguage,which is the set of physical mechanisms that we use to produce sounds orally. These mechanisms involve the throat, nasal cavities, tongue, lips, mouth, and jaw. The most common aspects of vocalics that we will focus on are pitch, pace, and volume, each of which we will cover below.

Pitch is how harmonically high or low you say something. The rate at which your vocal folds vibrate in your throat are responsible for the pitch of your voice. Low-frequency vibrations make for a lower-pitched sound, while higher frequency vibrations make for a higher-pitched sound. If you end the sentence on a high note (known as “uptalk”), you might be perceived as sounding uncertain about the claim (Dolcos et al., 2012). If you end it on a low pitch, it might sound like you are stating a fact confidently.

Rate, sometimes called pacing, refers to how quickly you utter your words. Often, beginning public speakers will talk fast out of nervousness or too much excitement. Their area of improvement then is learning to slow down to allow the audience to “digest” the words. In high-energy humorous speeches, the speaker might talk faster, whereas in more serious dramatic speeches, the speaker would slow down to build the drama. Consider this clip from the 1990’s hit show King of the Hill.

The use of pauses is a natural aspect of pacing. There are two types of pauses: grammatical and non-grammatical. Grammatical pauses are used to highlight something in a sentence or to build suspense. An example would be a host saying, “And the winner is … Corey,” where the ellipsis (…) is a pause to build suspense. Non-grammatical pauses are not planned and may occur when a speaker loses their train of thought or is self-correcting.

Volume refers to the loudness of the language being spoken. You might have a friend who is a “loud talker” and can be heard from far distances having conversations with someone within social distance. On the opposite end of the spectrum, you may have a friend who is a “soft talker” who may be hard to hear in loud settings. In any case, we may have expectations for volume in certain settings. At a football game, loudness is encouraged by fellow fans. In a fine-dining romantic restaurant, soft-talking is expected by fellow patrons.

Haptics

Haptics is the study of touch as a form of nonverbal communication. Touch is used in many ways in our daily lives, such as greeting, comfort, affection, task accomplishment, and control. You have likely engaged in a few or all of these behaviors today, probably without even thinking about it. If you shook hands with someone, hugged a friend, kissed your romantic partner, then you used touch to greet and give affection. If you visited a salon to have your hair cut, then you were touched with the purpose of task accomplishment. You may have encountered a friend who was upset and patted the friend to ease the pain and provide comfort. Finally, you may recall your parents or guardians putting an arm around your shoulder to help you walk faster if there was a need to hurry you along. In this case, your parent/guardian was using touch for control.

Several factors impact how touch is perceived. These factors are duration, frequency, and intensity. Duration is how long touch endures. Frequency is how often touch is used, and intensity is the amount of pressure applied. These factors influence how individuals are evaluated in social interactions. For example, researchers state, “a handshake preceding social interactions positively influenced the way individuals evaluated the social interaction partners and their interest in further interactions while reversing the impact of negative impressions (Dolcos et al., 2012). This research demonstrates that individuals must understand when it is appropriate to shake hands and that there are negative consequences for failing to do so. Importantly, an appropriately timed handshake can erase the negative effects of any mistakes one might make in an initial interaction!

Touch is a form of communication that can be used to initiate, regulate, and maintain relationships. It is a very powerful form of communication that can be used to communicate messages ranging from comfort to power. Duration, frequency, and intensity of touch can be used to convey liking, attraction, or dominance. Touch can be helpful or harmful and must be used appropriately to have effective relationships with family, friends, and romantic partners. Consider that inappropriate touch can convey romantic intentions where no romance exists. Conversely, fear can be instilled through touch. Touch is a powerful interpersonal tool along with voice and body movement.

Proxemics

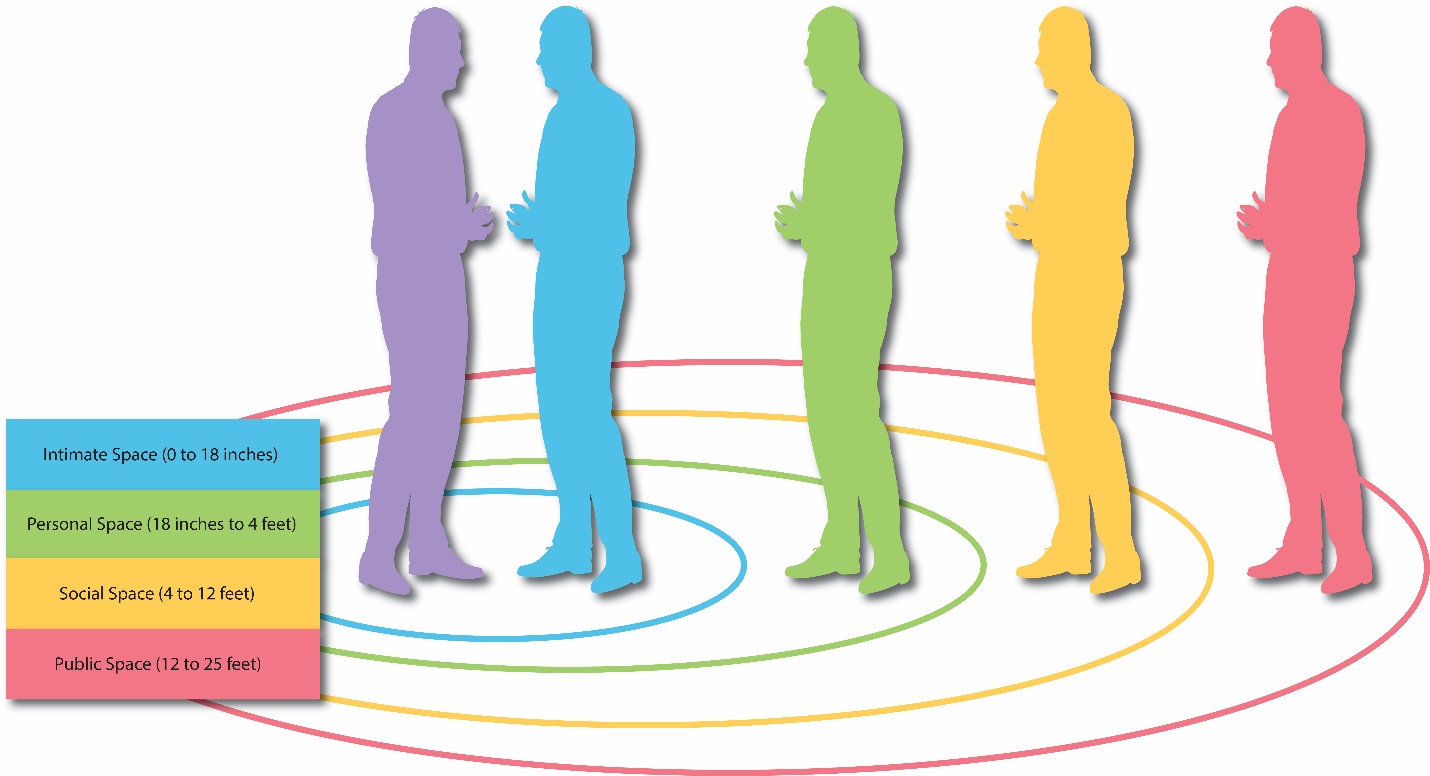

Proxemics is the study of communication through space. Space as communication was heavily studied by Edward T. Hall (1969, and he famously categorized space into four “distances. These distances represent how space is used and by whom.

Hall’s first distance is referred to as intimate space. This bubble ranges from 0 to 18 inches from the body. This space is reserved for those with whom we have close personal relationships, but not always. In the classroom, for example, you’re often required to sit little more than a foot away from your classmate. Context can dictate whether or not an 18 inch gap is intimate, or personal, which we’ll discuss next.

The second distance is referred to as personal space and ranges from 18 inches to 4 feet. You will notice that, as the distances move further away from the body, the intimacy of interactions decreases. Personal space is used for conversations with friends or family. If you meet a friend at the local coffee shop to catch up on life, it is likely that you will sit between 18 inches and four feet from your friend.

The next distance is social sapce, ranging from 4 feet to 12 feet. This space is meant for acquaintances. Like intimate space, social distance is relative. Again, in the classroom there is a good chance that you’re more than 12 feet away from your professor at any given time. Yet it’s the confines of the room that take a 15-30 foot gap and make it more social in nature.

Finally, the greatest distance is referred to as public space, ranging from 12 feet to 25 feet. In an uncrowded public space, we would not likely approach a stranger any closer than 12 feet. Consider an empty movie theatre. If you enter a theatre with only one other customer, you will not likely sit in the seat directly behind, beside, or in front of this individual. In all likelihood, you would sit further than 12 feet from this individual. However, as the theatre begins to fill, individuals will be forced to sit in Hall’s distances that represent more intimate relationships. How awkward do you feel if you have to sit directly next to a stranger in a theatre?

The Environment

The environment is everything around us and can be defined as any place, setting, location, surrounding in which something occurs. The physical environment plays a significant, but often underrated role in nonverbal communication (Jane, 2017; Patterson, 2016). Traditional dimensions include territory and how human beings utilize personal space (proxemics), inanimate objects even interior designs, furniture arrangement, lighting, colors, textures, and even time (chronemics, which we’ll get to in a moment.).

Consider the following questions:

- What message might a cluttered living room send?

- Is having desks split into two groups facing each other or in a circle the most effective arrangement for class discussions?

- Do you know someone who is guilty of ‘manspreading’ on public transit? Manspreading (or man-sitting) is when men sit “with their legs in a wide v-shape filling two or three single seats on public transport” (Patterson, 2016). This practice is clearly a high-power nonverbal display that violates social expectations of how public spaces should be utilized.

Manspreading is just one way in which we can use our bodies as an element of the environment. While there are physical characteristics about ourselves that we cannot change, we do have control over our clothing choices, grooming behaviors, such as hair style, and the artifacts with which we adorn ourselves, such as clothes and accessories. Have you ever tried to consciously change your “look?” Changes in hairstyle and clothes can impact how you are perceived by others. In addition to artifacts such as clothes and hairstyles, other political, social, and cultural symbols send messages to others about who we are, such as piercings and tattoos. Jewelry can also send messages with varying degrees of direct meaning. A ring on the “ring finger” of a person’s left hand typically indicates that they are married or in an otherwise committed relationship. Expensive watches can serve as status symbols, although only in certain communities. Tattoos can do the same thing, albeit in different contexts. Hopefully, this helps illustrate the interplay between appearance, proxemics, and environment.

In addition, we can use artifacts in the spaces we occupy, such as our home, office, or bedroom, to communicate about ourselves. The books that we display on our coffee table, the magazines a doctor keeps in his or her waiting room, or the placement of fresh flowers in a foyer all convey meaning to others. For example, imagine a bedroom that has the wall painted pink, a ruffle bedspread, and dolls displayed on the shelf. What do these items say about the person who occupies that room? What age would you think they are? Gender? What types of activities might you think the occupant likes by the various toys on display? In summary, whether we know it or not, our physical characteristics and the artifacts that surround us communicate much about us.

In the modern era we are forced to grapple with the virtual/online environment as complimentary to both our traditional environment and its own unique space. Research in this area is minimal, but growing. One easily accessible element of the online environment is the study of avatars. Avatars are computer-generated images that represent users in online environments or are created to interact with users in online and offline situations. Avatars can be created in the likeness of humans, animals, aliens, or other nonhuman creatures (Allmendinger, 2010). Avatars vary in terms of functionality and technical sophistication and can include stationary pictures like buddy icons, cartoonish but humanlike animations like a Mii character on the Wii, or very humanlike animations designed to teach or assist people in virtual environments.

Chronemics

Chronemics refers to the study of how time both affects and is an act of communication. Time can be classified into several different categories, including biological, personal, physical, and cultural time (Andersen & Andersen, 2005). Biological time refers to the rhythms of living things. Humans follow a circadian rhythm, meaning that we are on a daily cycle that influences when we eat, sleep, and wake. When our natural rhythms are disturbed, by all-nighters, jet lag, or other scheduling abnormalities, our physical and mental health and our communication competence and personal relationships can suffer. Keep biological time in mind as you communicate with others. Remember that early morning conversations and speeches may require more preparation for some, who are waking themselves up.

Moreover, some time is more rule governed than others. Formal time usually applies to professional situations in which we are expected to be on time or even a few minutes early. You generally wouldn’t want to be late for work, a job interview, a medical appointment, and so on. On the other hand, informal time applies to casual and interpersonal situations in which there is much more variation in terms of expectations for promptness. This is where terms like “fashionably late” come from. Knowing when to be on formal vs. informal time can make a big difference in the messages we send to others.

Personal time refers to the ways in which individuals experience time. The way we experience time varies based on our mood, our interest level, and other factors. Think about how quickly time passes when you are interested in and therefore engaged in something. You’ve likely listened to 20 minute lectures that felt like they were hours long, and half week long vacations that went by in an instant. Individuals also vary based on whether or not they are future or past oriented. People with past-time orientations may want to reminisce about the past, reunite with old friends, and put considerable time into preserving memories and keepsakes in scrapbooks and photo albums. People with future-time orientations may spend the same amount of time making career and personal plans, writing out to-do lists, or researching future vacations, potential retirement spots, or what book they’re going to read next.

Physical time refers to the fixed cycles of days, years, and seasons. In this way, physical time is universal. Physical time, especially seasons, can affect our mood and psychological states. Some people experience seasonal affective disorder that leads them to experience emotional distress and anxiety during the changes of seasons, primarily from warm and bright to dark and cold (summer to fall and winter). The same is true for seasonal depression. Thus, personal and physical time can blend in many ways.

Cultural time refers to how a large group of people view time. Polychronic people do not view time as a linear progression that needs to be divided into small units and scheduled in advance. Polychronic people keep more flexible schedules and may engage in several activities at once. Monochronic people tend to schedule their time more rigidly and do one thing at a time. A polychronic or monochronic orientation to time influences our social realities and how we interact with others.

Importantly, we can also use time as an act of communication. Let’s go back to our thought experiment on dating. Imagine that on Monday you matched with a person who is fairly good looking and moderately interesting. They ask you to go out with them Friday at 6 and you say yes. Then, on Wednesday, you match with a much more attractive and interesting person. This person asks you out as well – same time same day. What do you do? Do you maintain your commitment, or do you prioritize this new match? Whichever choice you make, you’re making use of time (specifically, an act of prioritization) to communicate to both of these people!

To sum, nonverbal communication comes in a wide variety of forms and presents itself across a wide variety of channels. But, as promised earlier, it’s not just enough to acknowledge what sorts of nonverbal messages exist, we must also understand how it works. In the next section we will take a deep dive into the various functions of nonverbal communication, and how each of these channels does work for us in our daily interactions.

7.3 – Functions of Nonverbal Communication

Now that we’ve covered such a wide array of nonverbal channels, it’s time to discuss how these channels function when we interact with others! Importantly, you’ll notice that in this conversation we often juxtapose nonverbal communication to its verbal counterpart. This is intentional. It’s so very necessary to understand that neither verbal nor nonverbal communication act alone. They are inextricably intertwined, and although humans tend to place more meaning on nonverbal communication, humans also heavily rely on verbal communication to draw that meaning! Let’s get into it.

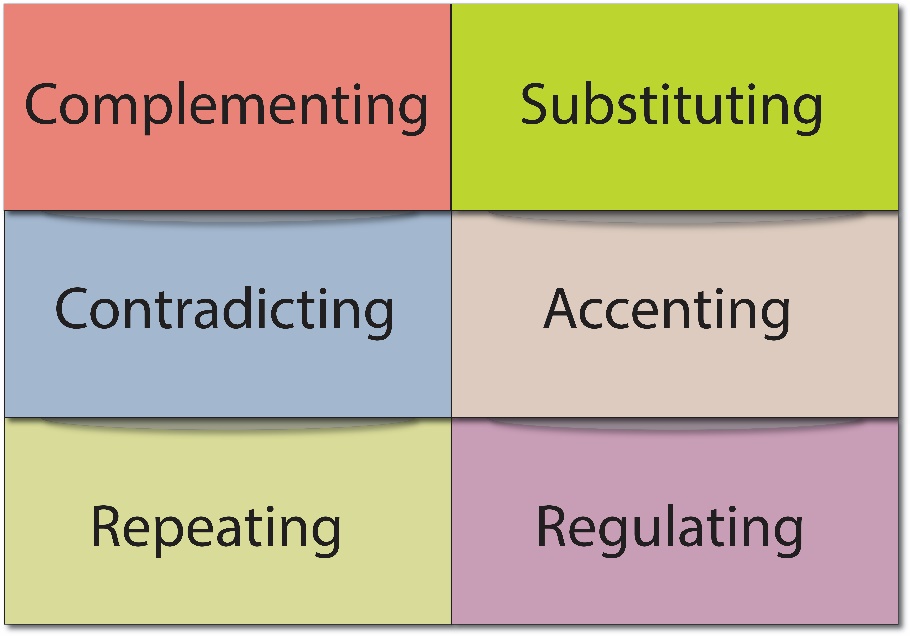

Research into nonverbal communication resulted in the discovery of multiple utilitarian functions of nonverbal communication. Consider the following six functions of nonverbal communication (Wrench et al., 2020):

Figure 7.9 – An illustration of the six primary functions of nonverbal communication. Image curtesy of libretexts.org.

Complementing is defined as nonverbal behavior that is used in combination with the verbal portion of the message to emphasize the meaning of the entire message. An example of complementing behavior is when a child exclaims, “I’m so excited” while jumping up and down. The child’s body is emphasizing the meaning of “I’m so excited.” Sometimes complimentary behaviors are intentional, other times they’re organic and unstoppable. For example, blushing deeply as you tell your significant over “I love you” for the first time. Yes, we can control some of this, but not all!

At times, a person’s nonverbal communication contradicts verbal communication. We already covered this when we discussed McKayla Maroney’s meme (“I told you, I’m fine!” she said, scowling and crossing her arms). The big question here is: when verbal and nonverbal communication contradict each other, which should you believe? Our instincts often tell us to believe the nonverbal, but this isn’t always the case. Always remember, “it depends” is one of the most consistent answers when it comes to question like this – and for good reason! Make sure you’re considering all options here.

Accenting is a form of nonverbal communication that emphasizes a word or a part of a message. The word or part of the message accented might change the meaning of the message. Gestures paired with a word can provide emphasis, such as when an individual says, “no *slams hand on table*, you don’t understand me.” By slamming the hand on a table while saying “no,” the source draws attention to the word. Words or phrases can also be emphasized via pauses. Speakers will often pause before saying something important. This use of pause is a form of accent in many ways, and for many different reasons.

Nonverbal communication that repeats the meaning of verbal communication assists the receiver by reinforcing the words of the sender. For example, nodding one’s head while saying “yes” serves to reinforce the meaning of the word “yes,” and the word “yes” reinforces the head nod. Now, this may sound a lot like complementing, and you’re not wrong. The difference here is that a repeating message is often emblematic and can act on its own. A child saying that they’re super excited while jumping up and down is complementary, but the jumping on its own doesn’t necessarily communicate excitement. Nodding one’s head yes, however, does indeed communicate that message on its own. Repeating nonverbal messages are more explicit than complementary messages.

Regulating the flow of communication is often accomplished through nonverbal behavior communication. You may notice your friends nodding their heads when you are speaking. Nodding one’s head is a primary means of regulating communication (this is an example of a backchannel cue). Other behaviors that regulate conversational flow are eye contact, moving or leaning forward, changing posture and eyebrow raises, to name a few. You may have noticed several nonverbal behaviors people engage in when trying to exit a conversation. These behaviors include stepping away from the speaker, checking one’s watch/phone, or packing up belongings. Note, regulators can begin, maintain, or end a conversation. It’s all about how you use them!

At times, nonverbal behavior serves as a substitute for verbal communication altogether. For example, a friend may ask you what time it is, and you may shrug your shoulders to indicate you don’t know. At other times, your friend may ask whether you want pizza or sushi for dinner, and you may shrug your shoulders to indicate you don’t care or have no preference. Again, note how explicit this is! Like repeating messages, substituting messages are highly emblematic in nature.

7.4 – Sending & Receiving Nonverbal Messages

Perhaps the most important function that nonverbal communication can serve is that of, well, communicating. We use your nonverbal messages to send messages to others. And, in turn, we listen to the nonverbal messages of others, and most of the time we don’t do it with our ears! So, let’s break down some of the most important elements of communicating with our nonverbal behaviors.

Nonverbal Communication Conveys Meaning

As we’ve already learned, verbal and nonverbal communication are two parts of the same system that often work side by side, helping us generate meaning. In terms of reinforcing verbal communication, gestures can help describe a space or shape that another person is unfamiliar with in ways that words alone cannot. Gestures also reinforce basic meaning—for example, pointing to the door when you tell someone to leave. Facial expressions reinforce the emotional states we convey through verbal communication. For example, smiling while telling a funny story better conveys your emotions (Hargie, 2011). A fluttering, bubbly tone to your voice can even further cement the meaning within this message.

One shockingly consistent finding in the nonverbal realm is that it contains a feature known as ontogenetic primacy – which is a fancy way of saying its the only form of communication we’re born with. For example, babies who have not yet developed language skills make facial expressions, at a few months old, that are similar to those of adults and therefore can generate meaning Oater et al., 1992). People who have developed language skills but can’t use them because they have temporarily or permanently lost them or because they are using incompatible language codes, like in some cross-cultural encounters, can still communicate nonverbally. Although it’s always a good idea to learn some of the local language when you travel, gestures such as pointing or demonstrating the size or shape of something may suffice in basic interactions.

Because nonverbal communication can contradict verbal communication, we run the risk of sending mixed messages (messages in which your words convey one thing and your nonverbals convey another). Consider the all important “friend-zone” as an example. Sometimes, when we’re talking with our crush, they might go so far as to indicate with their words that they’re not interested romantically. They may, however, engage in numerous intimate behaviors with us, like hugging, teasing, and extended bouts of one-on-one interaction. Mixed messages lead to uncertainty and confusion on the part of receivers, which leads us to look for more information to try to determine which message is more credible. If we are unable to resolve the discrepancy, we are likely to react negatively and potentially withdraw from the interaction (Hargie, 2011). Persistent mixed messages can lead to relational distress and hurt a person’s credibility in professional settings. This is why we view the friend-zone as a not-so-great place to be

Nonverbal Communication Influences Others

Nonverbal communication can influence people in a variety of ways, but the most common way is through deception. Deception is typically thought of as the intentional act of altering information to influence another person, which means that it extends beyond lying to include concealing, omitting, or exaggerating information. While verbal communication is to blame for the content of the deception, nonverbal communication partners with the language through deceptive acts to be more convincing. Since most of us intuitively believe that nonverbal communication is more credible than verbal communication, we often intentionally try to control our nonverbal communication when we are engaging in deception. Likewise, we try to evaluate other people’s nonverbal communication to determine the veracity of their messages. This is where all of those popular myths come from: looking up and to the left means you’re lying, a lack of eye contact means you’re fibbing, squirming and sweating must mean you’re being untruthful. But there’s a reason why lie detectors are no longer admissible in courts – because we’re more likely to misunderstand a behavior than for that behavior to actual be evidence of fabrication!

The fact that deception served an important evolutionary purpose helps explain its prevalence among humans today. Species that are capable of deception have a higher survival rate. Other animals engage in nonverbal deception that helps them attract mates, hide from predators, and trap prey (Andersen, 1999). To put it bluntly, the better at deception a creature is, the more likely it is to survive. So, over time, the humans that were better liars were the ones that got their genes passed on. But the fact that lying played a part in our survival as a species doesn’t give us a license to lie. These evolutionary factors are distal in nature – meaning that we don’t think about them in our day-to-day routine and they don’t drive our behavior. No, our deception comes from much more socially motivated places.

Aside from deception, we can use nonverbal communication to “take the edge off” a critical or unpleasant message in an attempt to influence the reaction of the other person. We can also use eye contact and proximity to get someone to move or leave an area. The delivering of “side eye” can tell someone you’re displeased with them. Alternatively, a soft, warm gaze can let another know you’re there for them. Nonverbal cues such as length of conversational turn, volume, posture, touch, eye contact, and choices of clothing and accessories are important, but often overlooked elements of influence. Consider the classic Milgram experiment, summed up in this short video.

A couple of important caveats. First, recent investigations have pushed back on the findings of the Milgram study. Essentially, in addition to being a tremendously unethical experiment, the study also used flawed methodology that, years later, we’ve learned to account for. Second, yes, deception did occur in this experiment, but it’s not the deception that matters here, it’s the perceived credibility. The only reason that the “teachers” continued with the experiment was due to instructions from someone who looked credible. Thus we see the role of nonverbal factors influencing the choices of others.

Nonverbal Communication Regulates Conversational Flow

Nonverbal communication helps us regulate our conversations so we don’t end up constantly interrupting each other or waiting in awkward silences between speaker turns. Pitch, which is a part of vocalics, helps us cue others into our conversational intentions. A rising pitch typically indicates a question and a falling pitch indicates the end of a thought or the end of a conversational turn. We can also use a falling pitch to indicate closure, which can be very useful at the end of a speech to signal to the audience that you are finished, which cues the applause and prevents an awkward silence that the speaker ends up filling with “That’s it” or “Thank you.” We also signal our turn is coming to an end by stopping hand gestures and shifting our eye contact to the person who we think will speak next (Hargie, 2011). Conversely, we can “hold the floor” with nonverbal signals even when we’re not exactly sure what we’re going to say next. Repeating a hand gesture or using one or more verbal fillers can extend our turn even though we are not verbally communicating at the moment.

Nonverbal Communication Affects Relationships

To successfully relate to other people, we must possess some skill at encoding and decoding nonverbal communication. The nonverbal messages we send and receive influence our relationships in positive and negative ways and can work to bring people together or push them apart. Nonverbal communication in the form of tie signs, immediacy behaviors, and expressions of emotion are just three of many examples that illustrate how nonverbal communication affects our relationships.

Tie signs are nonverbal cues that communicate intimacy and signal the connection between two people. These can be objects such as wedding rings or matching tattoos, actions such as sharing the same drinking glass, or touch behaviors such as hand-holding (Afifi & Johnson, 2005). Touch behaviors are the most frequently studied tie signs and can communicate much about a relationship based on the area being touched, the length of time, and the intensity of the touch. Kisses and hugs, for example, are considered tie signs, but the way we kiss matters just as much. Consider how you might kiss your grandma as opposed to how you might kiss your significant other.

Immediacy behaviors play a central role in bringing people together and have been identified by some scholars as the most important function of nonverbal communication (Andersen & Andersen, 2005). Immediacy behaviors are verbal and nonverbal behaviors that lessen real or perceived physical and psychological distance between communicators. They’re often simple and platonic behaviors like smiling, nodding, making eye contact, and nonintrusive touch Comadena et al., 2007). Immediacy behaviors are a good way of creating rapport, (a friendly and positive connection) with people. Skilled nonverbal communicators are more likely to be able to create rapport with others due to attention-getting expressiveness, warm initial greetings, and an ability to get “in tune” with others, which conveys empathy (Riggio, 1992). These skills are important to help initiate and maintain relationships.

Nonverbal Communication Expresses Our Identities

Nonverbal communication expresses who we are. Our identities (the groups to which we belong, our cultures, our hobbies and interests, etc.) are conveyed nonverbally through the way we set up our living and working spaces, the clothes we wear, the way we carry ourselves, and the accents and tones of our voices. Our physical bodies give others impressions about who we are, and some of these features are more under our control than others. Physical attractiveness, height, adornment, and the artifacts we decorate our selves/territory with can all speak volumes about who we are to others. Although we can temporarily alter our height or looks—for example, with different shoes or different color contact lenses—we can only permanently alter these features using more invasive and costly measures such as cosmetic surgery. We have more control over some other aspects of nonverbal communication in terms of how we communicate our identities. For example, the way we carry and present ourselves through posture, eye contact, and tone of voice can be altered to present ourselves as warm or distant depending on the context.

7.5 – Roles, Rules, and Norms of Nonverbal Communication

In the United States, we have a cultural tradition of dressing up for Halloween. This tradition dates back to ancient Celtic beliefs. Basically, in order to protect themselves from evil spirits on New Year’s Eve when the boundary between the living and the dead was most accessible, people hid behind animal skin costumes. Over the many hundreds of years, dressing up in costume has become less about hiding from spirits and more about the nonverbal expression of individuality. It’s now just…part of life. We have parties, events, TV marathons, and all sorts of merchandising to reinforce the cultural significance of Halloween, a near entirely nonverbal holiday.

That said, a failure to adhere to cultural norms surrounding nonverbal communication can have devastating blowback. Back in 2012, an Orange County high school made headlines with a dress-up day titled “Señores and Señoritas Day,” which was supposed to be a play on the word seniors. Canyon High School is located in Anaheim, California, and this event was intended to be a spirit day celebrating graduating seniors and California’s Mexican heritage. The event dated back to at least 2009. It made sense to celebrate Hispanic heritage in this town, as over 50% of residents were Latino at the time. However, the school’s administration did not properly specify guidelines for this event and broadly announced for students to wear Hispanic-themed attire.

The ambiguous instructions led to students showing up to school dressed as US Border Patrol agents, immigration agents, gardeners, a pregnant woman pushing a baby stroller, and gang members with bandanas and teardrop tattoos. While these may seem like extreme examples, could students have dressed up in anything that did not perpetuate stereotypes? Even with clear guidelines, how does one avoid reducing the Hispanic culture to stereotypes and caricatures? How did the administration not see that this event was the epitome of cultural appropriation? The answer is unclear, but one thing we can do proactively to limit events like this is to be aware of the power of our nonverbal messages.

Guidelines for Sending Nonverbal Messages

First things first, we’ve got to consider impression formation. Nonverbal cues account for much of the content from which we form initial impressions, so it’s important to know that people make judgments about our identities and skills after only brief exposure. Our competence regarding and awareness of nonverbal communication can help determine how an interaction will proceed and, in fact, whether it will take place at all. People who are skilled at encoding nonverbal messages are more favorably evaluated after initial encounters. This is likely due to the fact that people who are more nonverbally expressive are also more attention getting and engaging and make people feel more welcome and warm due to increased immediacy behaviors, all of which enhance perceptions of charisma.

Know that NVC affects interactions. Nonverbal communication affects our own and others behaviors and communication. Knowing this allows us to have more control over the trajectory of our communication, possibly allowing us to intervene in a negative cycle. For example, imagine being stuck in traffic on the way to an important job interview. Our frustration builds as it becomes more and more apparent that we’re going to be late. So we grip the steering wheel hard, we mumble about how stupid the other drives must me, our face heats up, and we tug at our shirt to loosen it. The more we do these reinforcing behaviors the angrier we become. Then, eventually, we show up to the interview and absolute mess and are less likely to get hired a a result. Increased awareness about these cycles can help you make conscious moves to change your nonverbal communication and, subsequently, your cognitive and emotional states (McKay et al., 1995). That said, overdoing these behaviors can feel deceptive and misleading, resulting in negative consequences and crossing the line into unethical communication.

As your nonverbal encoding competence increases, you can strategically manipulate your behaviors. This is extremely useful for those of us who work in customer service. As a waiter, you might learn the tendencies of your regulars, matching their nonverbal energy and building rapport. This can result in higher tips and an overall more pleasant work experience. The strategic use of nonverbal communication to convey positive messages is largely accepted and expected in our society, and as customers or patrons, we often play along because it feels good in the moment to think that the other person actually cares about us.

One specific tactic humans can use to build rapport is called mirroring – which involves the loose replication, but not imitation, of another person’s nonverbal tendencies. Humans have evolved an innate urge to mirror each other’s nonverbal behavior, and although we aren’t often aware of it, this urge influences our behavior daily (Alan & Pease, 2004). Think, for example, about how people “fall into formation” when waiting in a line. Our nonverbal communication works to create an unspoken and subconscious cooperation, as people move and behave in similar ways. When one person leans to the left the next person in line may also lean to the left, and this shift in posture may continue all the way down the line to the end, until someone else makes another movement and the whole line shifts again.

As you get better at monitoring and controlling your nonverbal behaviors and understanding how nonverbal cues affect our interaction, you may show more competence in multiple types of communication. For example, people who are more skilled at monitoring and controlling nonverbal displays of emotion report that they are more comfortable public speakers (Riggio, 1992). Since speakers become more nervous when they think that audience members are able to detect their nervousness based on outwardly visible, mostly nonverbal cues, it is logical that confidence in one’s ability to control those outwardly visible cues would result in a lessening of that common fear.

Understand How NVC Regulates Conversations. The ability to encode appropriate turn-taking signals can help ensure that we can hold the floor when needed in a conversation or work our way into a conversation smoothly, without inappropriately interrupting someone or otherwise being seen as rude. People with nonverbal encoding competence are typically more “in control” of conversations. This regulating function can be useful in initial encounters when we are trying to learn more about another person and in situations where status differentials are present or compliance gaining or dominance are goals. Although close friends, family, and relational partners can sometimes be an exception, interrupting is generally considered rude and should be avoided. Even though verbal communication is most often used to interrupt another person, interruptions are still studied as a part of chronemics because it interferes with another person’s talk time. Instead of interrupting, you can use nonverbal signals like leaning in, increasing your eye contact, or using a brief gesture like subtly raising one hand or the index finger to signal to another person that you’d like to soon take the floor.

Understand How NVC Relates to Listening. Part of being a good listener involves nonverbal-encoding competence, as nonverbal feedback in the form of head nods, eye contact, and posture can signal that a listener is paying attention and the speaker’s message is received and understood. As we learned in chapter five, active listening combines good cognitive listening practices with outwardly visible cues that signal to others that we are listening. Listeners are expected to make more eye contact with the speaker than the speaker makes with them, so it’s important to “listen with your eyes” by maintaining eye contact, which signals attentiveness. Listeners should also avoid distracting movements in the form of self, other, and object adaptors. Being a higher self-monitor can help you catch nonverbal signals that might signal that you aren’t listening, at which point you could consciously switch to more active listening signals.

Understand How NVC Relates to Impression Management. The nonverbal messages we encode help us express our identities and play into impression management, which is a key part of communicating to achieve identity goals. Being able to control nonverbal expressions and competently encode them allows us to better manage our persona and project a desired self to others—for example, a self that is perceived as competent, socially attractive, and engaging. Being nonverbally expressive during initial interactions usually leads to more favorable impressions. So smiling, keeping an attentive posture, and offering a solid handshake help communicate confidence and enthusiasm that can be useful on a first date, during a job interview, when visiting family for the holidays, or when running into an acquaintance at the grocery store. Nonverbal communication can also impact the impressions you make as a student. Research has also found that students who are more nonverbally expressive are liked more by their teachers and are more likely to have their requests met by their teachers (Mottet et al., 2004)

Increasing Nonverbal Competence

While it is important to recognize that we send nonverbal signals through multiple channels simultaneously, we can also increase our nonverbal communication competence by becoming more aware of how it operates in specific channels. Although no one can truly offer you a rulebook on how to effectively send every type of nonverbal signal, there are several nonverbal guidebooks that are written from more anecdotal and less academic perspectives.

Kinesics. As we discussed, there are a ton of different kinesic behaviors. As a result, there are a ton of different ways to become keenly aware of, and then monitor our kinesic displays. When it comes to gestures we want to make sure we’re using emblems, illustrators, and regulators only when appropriate. When on the phone, engage with gesticulations, they can help add subtle tonality to your voice! Be aware of your adaptors and how they influence your credibility. Are you scratching, picking, squirming, or fidgeting? How might that affect the ways that others see you? Don’t forget, even though we cannot discern meaning from any one nonverbal behavior per se, that doesn’t mean people don’t try to! Since many gestures are spontaneous or subconscious, it is important to raise your awareness of them and monitor them. Be aware that clenched hands may signal aggression or anger, nail biting or fidgeting may signal nervousness, and finger tapping may signal boredom.

As for eye contact, you need to know the cultural norms. Eye contact is useful for initiating and regulating conversations. So it might be helpful to “catch the eye” of another before speaking. Alternatively, avoiding eye contact or shifting your eye contact from place to place can lead others to think you are being deceptive or inattentive- unless of course you’re in Eastern Asia, in which case that lack of eye contact is considered respectful. Thus, make use of what’s known as civil intention with your eye contact. The notion of civil inattention refers to a social norm that leads us to avoid making eye contact with people in situations that deviate from expected social norms, such as witnessing someone fall or being in close proximity to a stranger expressing negative emotions (like crying). We also use civil inattention when we avoid making eye contact with others in crowded spaces (Goffman, 2010)

Lastly, it’s beneficial to be aware of your facial expressions. You can use facial expressions to manage your expressions of emotions to intensify what you’re feeling, to diminish what you’re feeling, to cover up what you’re feeling, to express a different emotion than you’re feeling, or to simulate an emotion that you’re not feeling (Metts & Planlap, 2002). Be aware of the power of emotional contagion (the spread of emotion from one person to another). Since facial expressions are key for emotional communication, you may be able to strategically use your facial expressions to cheer someone up, lighten a mood, or create a more serious and somber tone. Smiles are especially powerful as an immediacy behavior and a rapport-building tool. Smiles can also help to disarm a potentially hostile person or deescalate conflict!

Haptics. We want to be very, very careful with our use of touch, especially with people who we don’t know all that well. Remember that culture, status, gender, age, and setting influence how we send and interpret touch messages. In professional and social settings, it is generally OK to touch others on the arm or shoulder. Although we touch others on the arm or shoulder with our hand, it is often too intimate to touch your hand to another person’s hand in a professional or social/casual setting. One good rule to follow is the E-P-T rule, which stands for eyes, proxemics, touch. First, engage with eye contact. If it is reciprocated, you can try decreasing the space between you and the other person. If this is well received, you may then attempt physical contact. Above all, when it comes to touch, always be explicitly aware of the other person’s comfort level and adjust your behavior accordingly.

Vocalics. The good news about vocalics is that it comes a bit more naturally than some of the others, especially since it is so immediately apparent. That said, we sometimes let certain behaviors slip away from us, so there’s a few things to watch out for. Verbal fillers are often used subconsciously and can negatively affect the credibility and clarity of your message. In fact, verbal fluency is one of the strongest predictors of persuasiveness (Mehrbian,, 1971). Becoming a higher self-monitor can help you notice your use of verbal fillers and begin to eliminate them. Moreover, vocal variety increases listener and speaker engagement, understanding, information recall, and motivation. So having a more expressive voice that varies appropriately in terms of rate, pitch, and volume can help you achieve communication goals.

Proxemics. Like touch, we want to be extra careful with how we handle the balance between our and another person’s space. When breaches of personal space occur, it is a social norm to make nonverbal adjustments such as lowering our level of immediacy, changing our body orientations, and using objects to separate ourselves from others. We can also shift the front of our body away from others to disallow access to body parts that are considered vulnerable, such as the stomach, face, and genitals (Andersen, 1999). When we can’t shift our bodies, we might use coats, bags, books, or our hands to physically separate or block off the front of our bodies from others. Although pets and children are often granted more leeway to breach other people’s space, since they are still learning social norms and rules, as a pet owner, parent, or temporary caretaker, be aware of this possibility and try to prevent such breaches or correct them when they occur.

Chronemics In terms of talk time and turn taking, research shows that people who take a little longer with their turn, holding the floor slightly longer than normal, are actually seen as more credible than people who talk too much or too little (Andersen, 1999). Our lateness or promptness can send messages about our professionalism, dependability, or other personality traits. For most social meetings with one other person or a small group, you can be five minutes late without having to offer much of an apology or explanation. Consider, however, how your professor acts when you’re five minutes late to class versus how you might act when your professor is the one who is late. And remember, time can illustrate priorities. Quality time is an important part of interpersonal relationships, and sometimes time has to be budgeted so that it can be saved and spent with certain people or on certain occasions—like date nights for couples or family time for parents and children or other relatives.

7.6 – Conclusion

Activity 1: Distance Violations

You can test the importance of distance by deliberately violating the cultural rules for use of the proxemic zones outlined by cultural anthropologist Edward T. Hall:

- Join with a partner. Choose which one of you will be the perpetrator and which will be the observer.

- In three distinct situations, the perpetrator should deliberately use the “wrong” amount of space for the context. Make the violations as subtle as possible. You might, for instance, gradually move into another person’s intimate zone when personal distance would be more appropriate. (Be careful not to make the violations too offensive!)

- The observer should record the verbal and nonverbal reactions of others when the distance zones are violated. After each experiment, inform the people involved about your motives and ask whether they were consciously aware of the reason for any discomfort they experienced.

Activity 2: Micro-expressions

Test your ability to detect micro-expressions for free by using the link: http://www.microexpressionstest.com/micro-expressions-test/

How well did you interpret the micro-expressions?

Now retake the test — this time with a partner — to see if you can agree on what micro-expression is being displayed. Then address the following:

● Discuss why you chose the expression you did.

● Talk about how easy or difficult it is to interpret these brief nonverbal cues.

References:

- Afifi W. & Johnson, M. L. (2005). The Nature and Function of Tie-Signs. In The Sourcebook of Nonverbal Measures: Going beyond Word, (Ed. Valerie Manusov). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Allmendinger, K. (2010). Social Presence in Synchronous Virtual Learning Situations: The Role of Nonverbal Signals Displayed by Avatars. Educational Psychology Review 22(1). 42.

- Anderson, P. (1999). Nonverbal Communication: Forms and Functions Mountain View, CA: Mayfield. 2–8.

- Andersen, P. A. & Andersen, J. F. (2005). Measures of Perceived Nonverbal Immediacy. In The Sourcebook of Nonverbal Measures: Going beyond Words, (Ed. Valerie Manusov), Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Birdwhistell, R. L. (1970). Kinesics and context: Essays in body motion communication. University of Pennsylvania Press, p. xiv.

- Comadena, M. E., Hunt, S. K., & Simonds, C. J. (2007). The Effects of Teacher Clarity, Nonverbal Immediacy, and Caring on Student Motivation, Affective and Cognitive Learning. Communication Research Reports 24(3). 241-248.

- Dolcos, S., Sung, K., Argo, J. J., Flor-Henry, S., & Dolcos, F. (2012). The power of a handshake: Neural correlates of evaluative judgments in observed social interactions. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 24(12), 2292-2305.

- Eckman, P and Friesen, W.V. (1969). Head and body cues in the judgement of emotion: A reformulation. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 24, 711-724.

- Goffman, E. (2010). Relations in Public: Microstudies of the Public Order New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

- Guerrero, L. K. & Floyd, K. (2006). Nonverbal Communication in Close Relationships. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum,.

- Hall, E.T. (1969). The hidden dimension. Doubleday.

- Hargie, O. (2011). Skilled Interpersonal Interaction: Research, Theory, and Practice, 5th ed. London: Routledge.

- Ivy, D. K., & Wahl, S. T. (2019). Nonverbal communication for a lifetime (3rd ed.). Kendall-Hunt; pg. 155.

- Jane, E. A. (2017). ‘Dude… stop the spread’: antagonism, agonism, and manspreading on social media. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 20(5), 459-475.

- Martin, J. N & Nakayama, T. K. (2010). Intercultural Communication in Contexts, 5th ed. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

- McKay, M., Davis, M., & Fanning, P. (1995). Messages: Communication Skills Book, 2nd ed. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

- Mehrabian, A. (1971). Silent messages. Wadsworth.

- Metts S. & Planlap, S. (2002). Emotional Communication. In Handbook of Interpersonal Communication, 3rd ed.. (Eds. Mark L. Knapp and Kerry J. Daly). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Mottet, T. P., Beebe, S. A., Raffeld, P. C., & Paulsel, M. L. (2004). The Effects of Student Verbal and Nonverbal Responsiveness on Teachers’ Liking of Students and Willingness to Comply with Student Requests, Communication Quarterly 52(1). 27–38.

- Oster, H., Hegley, D., & Nagel, L. (1992). Adult Judgments and Fine-Grained Analysis of Infant Facial Expressions: Testing the Validity of A Priori Coding Formulas. Developmental Psychology 28,(6 )1115–1131.

- Patterson, M. (2018). Nonverbal Interpersonal Communication. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. Retrieved 5 Mar. 2020, from https://oxfordre.com/communication/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228613-e-657

- Patterson, M. L., & Quadflieg, S. (2016). The physical environment and nonverbal communication. In APA handbook of nonverbal communication (pp. 189-220). American Psychological Association.

- Pease A.. & Pease, B. (2004). The Definitive Book of Body Language (New York, NY: Bantam.

- Riggio, R. E. (1992). Social Interaction Skills and Nonverbal Behavior. In Applications of Nonverbal Behavior Theories and Research (Ed. Robert S. Feldman). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Sheldon, W. H. (1940). The varieties of human physique. Harper and Brothers.

- Spielman, R. M., Dumper, K., Jenkins, W., Lacombe, A., Lovett, M., & Perlmutter, M. (2014). Psychology. OpenStax.

- Tsai, J. (2021). Culture and emotion. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba Textbook Series: Psychology. DEF Publishers.

- Wrench, J. S., Punyanut-Carter, N. A. & Thweatt, K. S. (2020). Interpersonal Communication – A Mindful Approach to Relationships. SUNY New Paltz & SUNY Oswego via OpenSUNY