12 Chapter 12 – An Introduction to the Dark Side of Interpersonal Communication

History, Definitions, Deception, Gaslighting, and Jealousy

Robert D. Hall, PhD

Introduction

Parents lie to their children all the time, and it is a pretty universal phenomenon. In the United States’ folklore, many of our parents tell their children that Santa Claus delivers presents to good children and coal to bad children. In Iceland, parents tell their children that the Yule Lads give a small gift to good children and a raw potato to bad children. In both cases, these are not true. If something is not true, it is lie, and lying is bad, right? Well, most of us would not consider these lies our parents told us as “bad” or “evil.” Rather, United States culture would say that not practicing the tradition of lying about Santa Claus would be the “bad” thing. So, how can telling the truth be “bad” and lying be “good?” When we consider the dark side of interpersonal communication, we can begin to effectively answer these questions. Thus, in this chapter, we will explore the dark side of interpersonal communication, beginning with the history of the dark side, defining the dark side today, and providing examples of how we see the dark side in our lives.

12.1 Brief History of the Dark Side of Interpersonal Communication

To understand the dark side of interpersonal communication, it is important for us to first know why we need to study the dark side. For context, interpersonal communication is a relatively young discipline in academia, becoming formalized first in the 1970s. During the 1970s, there was a strong public outcry for peace and positivity amidst controversial and tumultuous wartimes. As such, our early interpersonal communication studies largely reflected the cultural ideals of the time, making it seem like the ultimate goal of interpersonal communication was always to become more intimate, or emotionally or psychologically connected (Dillow, 2023), with the other. Parks (1982) critiqued this era of research as exemplifying the bias of intimacy. The exceptional bias toward positivity lead to early findings such as: the more we disclose, the closer we become (Altman & Taylor, 1973) and being physically attracted to someone is beneficial to a relationship (Berscheid & Waister, 1974).

However, we know that these phenomena aren’t always inherently beneficial. For example, one of the authors of this book once sat on an overseas flight. During the flight, the person next to him talked for hours about his issues with sleeping. However, once this flight ended, the author did not feel any closer to this individual. In fact, the author felt less intimate with this person. In this way, the author exemplified what Petronio (2002) may call a reluctant confidant, or someone who receives personal, private information from another person but does not want to receive such information. This example demonstrates why Parks’s (1982) critique is so important: we should not categorize behaviors into simply “good” or “bad.”

Along with Parks (1982), Cupach and Spitzberg (1994) provided us with a first look at the dark side of interpersonal communication. Cupach and Spitzberg (1994) initially provided us with the dark side of interpersonal communication as “social interaction that is difficult, problematic, challenging, dysfunctional, distressing, and disruptive” (p. vii). Later on, Spitzberg and Cupach (1998) expanded this definition, attempting to create a typology of behaviors that could be considered dark-sided such as betrayal, deviance, bullying, sexual harassment, unrequited love, and social incompetence. However, these authors were still not satisfied as attempting to create a typology of dark-sided interpersonal behaviors could not possibly account for all topics that could be considered a part of the dark side.

12.2 Defining the Dark Side Today

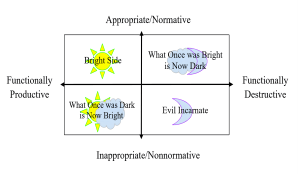

Today, the dark side of communication consists of two key dimensions: appropriateness/normativity, or the degree to which something is considered acceptable by society, and functionality, or the degree to which something serves to improve a relationship (Spitzberg & Cupach, 2007). The light and dark sides of communication are tied to each other as acceptable behaviors can lead to negative outcomes and unacceptable behaviors can lead to positive outcomes. This is called functional ambivalence, or the idea that behaviors in and of themselves are neither good nor bad. Rather, as dark side scholars, we consider social and relational appropriateness and norms along with whether a behavior is/was beneficial to a relationship. When we consider our two dimensions of the dark side of interpersonal communication, Spitzberg and Cupach (2007) provided us with four quadrants of the dark side (figure 1.1). To effectively define the dark side, we will next consider each quadrant of the dark side.

Quadrants of the Dark Side

When evaluating appropriateness/normativity and functionality, we consider where our behaviors may fall along these dimensions: the bright side, what once was bright is now dark, what once was dark is now bright, and the evil incarnate. To help explain each of these, we will describe them in terms of (a) the dimensions and (b) an example of providing social support to a friend after learning they failed a test. To begin, we will first examine the bright side.

The Bright Side. First, the bright side quadrant is conceptualized as behaviors that are deemed both appropriate/normative and functionally beneficial to the individuals and relationship. Suppose your friend, Inez, just texted you that she failed a test. Being her friend, you respond saying you are sorry and ask if there’s anything you can do to help her. Inez thanks you for being such a great friend. When considering the dark sided dimensions, we would consider this behavior as part of the bright side because your response would be considered appropriate/normative in this scenario, and it is/was beneficial to the relationship in question. However, not all behaviors that seem “bright” stay “bright,” and we will consider this idea next.

What Once was Bright is Now Dark. Second, the what once was bright is now dark quadrant is conceptualized as behaviors that are deemed both appropriate/normative, but they end up being functionally destructive to the individuals and relationship. Suppose that Inez texted you that she failed a test. As her friend, you respond that you are sorry, and you ask her if there’s anything you can do to support her. She says that she just needs some alone time. However, you think she needs a pick-me-up, so you bake her cupcakes and head to her dorm room. You knock on the door, and she answers. She says, “Oh…thank you, I guess. I’m not really in the mood for company…like I told you.” She then shuts the door, leaving you standing there. In this scenario, it is likely that both of your feelings were hurt in some way. You may feel that she was ungrateful for your gift, but she may feel like you didn’t respect the clear boundaries she set up. In this instance, we would say this behavior falls under the what once was bright is now dark quadrant. As a society, we may say that baking your friend cupcakes and delivering them to her after finding out some bad news is an appropriate/normative thing to do as a friend. However, despite appearing “bright,” this behavior was actually destructive to the relationship.

What Once was Dark is Now Bright. Third, the what once was dark is now bright quadrant is conceptualized as behaviors that are deemed inappropriate/nonnormative, but they end up being functionally productive or beneficial to the individuals and relationship. Suppose Inez texted a friend, Cam, that she failed a test and she is really sad about it. Cam then tells you that Inez failed a test and is upset about it. In response, you go to Inez’s dorm room and offer to hang out with her and be there to support her during this difficult time. Inez agrees to hanging out, and, at the end of the night, says she is grateful that Cam told you about the test as she feels much better now. As a society, we may say that sharing sensitive private information about others without their knowledge, potentially a form of gossip, could be inappropriate. Additionally, acting on such knowledge could further exacerbate this inappropriateness. However, we see in this scenario that Inez is not upset about the “inappropriate” behavior. Instead, what was once dark has become bright, showing that interpersonal behaviors initially thought of as “bad” may actually end up “good.” Still, some behaviors do not turn towards the “good” at all.

Evil Incarnate. Finally, the evil incarnate quadrant is conceptualized as behaviors that are deemed inappropriate/nonnormative and are functionally destructive to the individuals and relationship. Suppose that Inez texted us that she failed a test and is feeling upset about it. Instead of talking to her about it, you decide to tell your friends about her failure. Rather than offering her support, you and your friends decide to create a TikTok dance about Inez’s failure to try to get a following to encourage her to not give up, and the dance goes viral throughout campus. Inez ends up dropping out of college out of embarrassment and never speaking with you again. As a society, we would likely say that sharing such private information in such a public fashion would be inappropriate. Additionally, we see that the behavior was destructive to both Inez and the relationship.

Final Thoughts on the Four Quadrants. These quadrants are meant to demonstrate that any interpersonal behavior, such as social support, can be evaluated based on two dimensions: appropriateness/normativity and functionality. The quadrants further demonstrate the notion of functional ambivalence which tells us that any interpersonal behavior is neither “good” nor “bad,” but just is. We, as a society, tend to have norms for what we deem appropriate behavior, but these behaviors aren’t always beneficial to a relationship. In the examples above, we saw how social support, a behavior we may think is “good” (and it certainly can be “good”), can actually be detrimental to a relationship.

Figure 1.1: Four Quadrants of the Dark Side

Adapted from Brian H. Spitzberg and William R. Cupach, The Dark Side of Interpersonal Communication 2nd ed., p. 6.

So…What is the “Dark Side?”

Now that we have defined the quadrants of the dark side, we can reflect on what it means to study the “dark side” of interpersonal communication. Rather than a field of study that examines only “negative” aspects of interpersonal communication (Cupach & Spitzberg, 1994) or a typology of behaviors (Sptizberg & Cupach, 1998), we follow Dillow’s (2023) definition, based on Spitzberg and Cupach’s (2007) refinement of the dark side of interpersonal communication, where “the dark side functions more as a perspective or way of looking at things; it is a way of asking questions that draws attention to the inappropriate and destructive elements of all kinds of behaviors, even those that ostensibly begin as, are intended as or are usually evaluated as positive” (p. 10). With this definition, Dillow (2023) demonstrates how the dark side allows us to explicitly study and reflect on the gray areas of interpersonal communication, which largely reflects how we live our interpersonal lives.

In the next section, we are going to take a look at how we may be able to tell where a behavior will fall into the dark side.

Determining the Darkness

Whether you believe a communication behavior falls on the light or the dark side, may in large part be determined by how you perceive the situation, type of relationship, and the other person’s intentions. Numerous factors can determine whether someone perceives a communication behavior to be aversive or not (Kowalski, 2019). Inspired by Kowalski’s 2019 book, Behaving Badly: Aversive Behaviors in Interpersonal Relationships, we have created a set of questions to ask yourself to help understand if communication in your relationships falls on the dark side:

- Do certain people in your life leave you feeling like you doubt yourself and questioning your perceptions? Certain communication behaviors from the dark side can negatively impact our self-concept and self-esteem.

- Is there a power imbalance in the relationship? Relationships with power imbalances, such as between a boss and employee or parent and child, are more likely to experience aspects of the dark side.

- How close are you to the other person? The closer the relationship, the more likely we experience pain when faced with communication from the dark side.

- How frequent is the questionable communication behavior? A one-time transgression can be forgiven, but negative repeated behaviors are more likely to fall into the dark side.

- How severe is the communication behavior? Mild behavior may be accepted, but even a one-time severe occurrence can derail a relationship.

- Does the behavior interfere with your basic psychological needs, such as the need to belong, have a sense of control, and experience self-esteem?

As you reflect on your answers to these questions, you may notice that there are a variety of communication behaviors that fall into both the light and dark sides of communication. In the rest of this chapter, we review a few behaviors that are typically thought of as “dark”: deception, gaslighting, and jealousy.

12.3 Deception

As mentioned at the start of this chapter, deception is a commonplace and perhaps universal behavior. From Santa Claus to the Yule Lads, parents have a knack for deceiving children from the very start despite being perhaps one of our most trusted relationships. Yet, we wouldn’t inherently call this a “bad” thing as a society, which means that sometimes deception is a “good” thing. Given the nuance in how we, as a society, determine “good” from “bad” forms of lying, it is imperative for us to begin with answer to the question: What is deception?

Dillow (2023) cites Zuckerman et al.’s (1981) definition of deception “as intentionally transmitting (or strategically failing to transmit) information to create a belief in the target [of the deceptive act] that the sender knows or believes to be false” (p. 106). Buller and Burgoon (2006) give us a more simplistic definition of deception as “deception occurs when communicators control the information contained in their messages to convey a meaning that departs from the truth as they know it” (p. 205). Taken together, deception can function to strategically manipulate information while impacting the dynamic nature of one’s relationship.

What do you think this means in a relationship when a relational partner decides to deceive someone? Theorists who study deception focus on how and why people engage in deception and try to get away with it and how the other person tries to figure out whether or not to believe the deceptive act (e.g., Buller & Burgoon, 2006). Whether or not a relationship can overcome deception really depends on that interplay between how someone responds when faced with deception and how the deceiver responds back in order to repair the relationship. Given that different types of deception can lead to different responses, we will next overview the types of deception.

Types of Deception

Not all of our lies are built the same. Later, we will discuss the various reasons for why we may deceive, but we first need to learn the different types of deception that might occur in our relationships: deception by omission and deception by commission. These two types of deception differ according to the level of distortion that is involved and how much potential impact there is on a relationship because of how this deception is perceived. We will first examine deception by omission.

Deception by omission involves intentionally holding back some of the information another person has requested or would be expected to share. For example, a relational partner might ask why you didn’t respond to their text last night, and you could say you were busy while leaving out who you were busy with. Omitting information can violate relational expectations and can have an impact on the trust and intimacy that was already built in the relationship. If our relational partners find out that we have violated their expectations of trust and undermined it through deception by omission, the trust in the relationship may decline. If deception by omission does lead to relationship decline, we will then have to spend some time determining how to repair such a relationship.

When we commit deception by commission, we deliberately communicate false information. This type of deception goes beyond just a strategic withholding of information. When there is deception by commission, there is an intentional level of control of both the quantity and quality of information the relational partner receives. This type of deception includes:

- Lies of convenience (commonly referred to as white lies): This is when information is presented as slightly false and there may be minimal consequence to presenting the information as such. Oftentimes, these white lies are communicated to enable one to feel less guilty or to ensure that someone’s feelings are not hurt. Take the classic example of if one’s partner asks, “Does this outfit make me look fat?” If we say, “yes,” our partner may feel hurt even though the response was honest. Would it have been better for us to tell a white lie and just say, “no?” Thus, white lies often function as what’s called a social lubricant—a social behavior “that essentially enhances our ability to get along with each other by reducing conflict among [those in the interaction]” (Dillow, 2023, p. 109).

- Lies of exaggeration: An exaggeration is a type of deception by commission that includes the embellishing of facts or the stretching of the truth (which can get more elaborate over time). When someone exaggerates or overstates by playing with the boundaries of what is considered factual or truthful, this type of misrepresentation can lead to mistrust in a relationship given the blurring of boundaries between truth and fiction.

- Bald-faced lies: A bald-faced lie is a type of deception that involves an outright falsification of information. When someone communicate a bald-faced lie, there exists an intent to truly deceive someone.

“I’m not a liar!” by kewl is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Now that we’ve reviewed two broad categories of the types of deception, we will next discuss our motivations for engaging in deceptive behaviors.

Why Do We Deceive?

If we know that deception in a relationship carries with it the risk of destroying the trust we have built in our relationships, why would we decide to deceive someone in the first place? There are many reasons we might contemplate or use to determine and justify engaging in an act of deception:

- Partner-focused motives for deception aim to protect and avoid hurting someone (e.g., hurt, worry, or psychological harm, Dillow, 2023). Our example under “lies of convenience” would likely fit into this motivation.

- Self-focused motivations for deception aim to avoid undesirable consequences that would come from being honest instead (e.g., protect our own resources, gain power/control, avoid personal negative outcomes, Dillow, 2023).

- Relationship-focused motivations for deception aim to preserve the relationship from harm. Here, we may try to avoid any type of unpleasant interaction with our relational other and avoid potential damage to the shared relationship. For example, if you met your ex-lover for coffee with interest only in being platonic, but we only tell our partner we met a friend for coffee to avoid conflict. These often start with good intentions, but they could have exacerbated negative effects in the long term if the deception is discovered.

Reflect on your past relationships and times you have engaged in any level of deception or felt you were deceived, and consider why. Do these reasons seem reasonable to you? We may find we can justify reasons (big or small) on why we might need to deceive in a relationship, but we also have to consider the short-term and long-term effects on a relationship if deception becomes commonplace.

Every communication act has a consequence, and we should be prepared to accept these consequences should we choose to engage in any form of deception in our relationships. First and foremost, as indicated earlier, if our relational partners find out we have withheld any information, and they perceive us to be lying, there will likely be some kind of harm to the relationship and/or a loss of trust. Perhaps our relational partner becomes more guarded on whether to completely trust us in future interactions. There may also be collateral damage or harm to others who aren’t directly involved simply because they are in our personal network and may peripherally experience an after effect of the deception.

However, the varying motivations for deception come with various levels of forgiveness. The more altruistic our deception, the more appropriate or forgivable the deceptive act. For example, the deceptive act of telling children about folk heroes often does not lead to long-lasting trust issues with one’s parents despite being a long-term deceptive act. Here, the deceptive act is seen as more altruistic, or for the sake of the other, and thus not a grievous offense.

Now that we have covered deception, its types, and various motivations for deception, we will next explore gaslighting.

12.4 Gaslighting

In 2018, Oxford Dictionaries named gaslighting one of its most popular words. For gaslighting to take place, it takes at least two people: the gaslighter, the one who creates doubt and confusion; and the gaslit, the one who questions their perceptions as a result of the gaslighter’s actions. Thus, gaslighting is a behavior where the gaslighter twists and exploits the gaslit’s words, emotions, and experiences to make the gaslit person feel like they’re either imagining or exaggerating events that occurred in the past.

If we find ourselves on the receiving end of gaslighting, we may find ourselves manipulated to the point where we begin to doubt our thoughts and perceptions of events, our emotions, and even our self-concept. To illustrate, if a wife tells her husband that she is overwhelmed with housekeeping and needs more support from him, and he responds that he does 90% of the cleaning (when he does not), and doesn’t know what she’s talking about, he gaslighted her. The use of gaslighting can not only cause someone to doubt themselves, but it is often considered a form of abusive communication that can negatively impact an individual’s mental health and well-being. Consider the story of Chanel Miller, who was inadvertently a victim of gaslighting from her family:

In the New York Times bestselling memoir Know My Name, Chanel Miller described the awful night when Brock Turner sexually assaulted her behind a dumpster on the campus of Stanford University. In a haunting passage, Miller recounted listening to friends and coworkers discuss the case without knowing that she was “Emily Doe,” the name assigned to her in press coverage of the assault. These well-meaning friends and colleagues pondered why a non-student would attend a university party, what she wore that night, and whether she enjoyed it because, after all, the assailant was a sexy jock. Later, Miller recalls the case prosecutor’s relief upon meeting her boyfriend: an older, employed, handsome, and athletic man. Miller’s own testimony that she was unconscious and could not consent to sex seemed to mean less than her boyfriend’s social desirability in a jury’s assessment of whether she had really been assaulted. (Graves & Spencer, 2022)

Gaslighting can be used in a variety of interpersonal relationships for a variety of reasons. Gaslighting can occur in romantic partnerships, with family, friends, and even with co-workers or a boss. For gaslighting to occur, both parties must value the relationship, there is usually unequal power between the partners, and the target of gaslighting does not want to lose the relationship and needs approval. Stressful relationship topics such as money, sex, child-rearing, and other complex issues can trigger gaslighting in an effort to diffuse tension and conflict, attempt to control the situation, and to ease anxiety (Stern, 2007). Although gaslighting techniques can be a strategic approach used by a person or group, often people who use gaslighting techniques are unaware of what they are doing. Thus, we will next describe some common forms of gaslighting to help us identify if we are being gaslit or the ones engaging in gaslighting behavior.

Common Forms of Gaslighting

Below, we list some common forms of gaslighting:

- Blaming the other person for the problem;

- o If there is a relational problem, the blame typically falls on both individuals to some extent. In terms of gaslighting, blaming the other person falls more in line with scapegoating.

- Minimizing the seriousness of the event;

- Diminishing the other person’s self-concept;

- Ridiculing the other person;

- Verbal attacks;

- Changing the subject;

- Blatant lying;

- Denial that something occurred.

To illustrate, consider this scenario:

Rachel and her new boyfriend Daniel are out for the evening with some of his friends. During the evening, Daniel makes a sexually explicit and vulgar comment at Rachel’s expense. Later that evening on their way home, Rachel lets Daniel know she is unhappy with the comment. First, Daniel outright denies that he made such a comment (denial). Daniel then blames Rachel, telling her that the situation is her fault, and claiming that she is so uptight his friends will never like her (scapegoating). He ends up saying “we both know you are just too sensitive” (diminishing self-concept). Rachel is left questioning her perception of the evening and wondering if she is being too sensitive.

Stern (2019) identified several common phrases that can be used by gaslighters to manipulate the other person, including:

- You’re so sensitive!

- You know that’s just because you are so insecure.

- Stop acting crazy. Or: You sound crazy, you know that, don’t you?

- You are just paranoid.

- I was just joking!

- You are making that up.

- It’s no big deal.

- You’re overreacting.

- You are always so dramatic.

- Don’t get so worked up.

- That never happened.

- You’re hysterical.

- There you go again!

- You are so ungrateful.

- Nobody believes you, why should I?

Chances are most people have experienced some form of gaslighting at some point in their lives (Stern, 2019). If you are a victim of gaslighting you may:

- Constantly second-guess yourself;

- Have difficulties making simple decisions;

- Continually ask yourself, “Am I being too sensitive?”;

- Feel confused or even “crazy”;

- Always apologize to your abuser;

- Not understand why you’re not happier when you have so many good things in your life;

- Feel as if you can’t do anything right;

- Wonder if you’re a “good enough” spouse/employee/friend/person.

Take some time to reflect on your answers to the questions. If you answer “yes” to one or more questions, you may be in a relationship where gaslighting is occurring. If you believe you are caught in the gaslight tango, developing your toolbox of communication skills can help you form healthy responses. Thus, we will next highlight some ways to respond competently to gaslighting behaviors.

Boston – Beacon Hill / Gaslight Lamp & Fire Escape by David Ohmer from Flicker licensed under CC BY 2.0.

How to Respond to Gaslighting with Communication Competence

It is important to recognize that gaslighting can have damaging effects on an individual’s self-concept, mental health, and overall well-being over time. If you find yourself using the gaslighting techniques described earlier, work on breaking the cycle by developing your assertiveness, emotional intelligence, and conflict management strategies to better address problems as they arise. If you believe that someone in your life is gaslighting you, it is worthwhile to develop a communication response strategy. Below, we offer some tips on how to develop such a response strategy to gaslighting:

- Learn to recognize gaslighting when it is happening.

- Practice assertive communication to stand up for yourself without exacerbating the issue.

- Check your perceptions with yourself and the other person. For example, if your partner criticizes you, rather than becoming defensive, use perception checking to try and get to the heart of the issue.

- Set boundaries with simple communication statements such as “I am uncomfortable with the direction of this conversation. We can come back to it later,” “It may not be your goal to criticize me, but I feel hurt, and I do not want to continue this conversation right now,” or, “I know you see the situation one way, but I don’t agree with you.”

- Seek feedback and support from people outside of your relationship.

- Consider consulting a therapist or counselor. If the gaslighting occurs at work, contact Human Resources.

Now that we have covered gaslighting, how to identify gaslighting behaviors, and how to respond to gaslighting, we will next cover jealousy.

12.5 Jealousy

Like with deception and gaslighting, jealousy is perhaps a more common experience than we give credit to. If you are like most people, you may have experienced both ends of jealousy, including feeling the emotion and finding yourself in a relationship with a jealous partner. In this section, we will begin this section with a definition of jealousy, followed by types of jealousy, and concluding with responses to jealousy.

Defining Jealousy

Jealousy is a complex interpersonal experience that is often conflated with words such as envy and rivalry. Thus, it is important for us to begin with defining each of these terms to better understand what we mean when we experience jealousy. First, jealousy is defined as “an interactive, interpersonal experience…[that] entails the need to protect and defend a valued relationship from the threat of a perceived or actual third-party rival” (Bevan, 2013 as cited in Dillow, 2023, p. 84). For example, if you typically eat lunch on Tuesdays with your best friend, but that friend cancels to meet a different friend for lunch, you may experience jealousy given the threat of a third-party rival in this scenario. When experiencing jealousy, we have something that another person wants, and we are jealous of the threat this other person—third-party—poses to us.

Envy is what we experience when we wish we “had some positive quality or commodity that another person possesses” (Dillow, p. 85). For example, one of your authors went to the Black Friday sale in an attempt to purchase Taylor Swift’s “Tortured Poets Department” vinyl. He overslept and did not make it time, but saw that someone in line had a copy in their hands. The author experienced envy because this person had a commodity (i.e., the vinyl album) that your author did not have.

Rivalry is what occurs “when at least two people compete for some reward that neither of them currently possess…or that both of them have in some measure but are competing against each other to get more of/hold on to” (Dillow, p. 85). Suppose that one of your authors woke up on time and made it to the Black Friday sale. If he and the other customers were standing around the kiosk with the vinyl albums, they may view each other as rivals given that none of them have what they want, but they are aiming to compete for the same reward.

“Jealousy” by Ktoine is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Thus, while jealousy, envy, and rivalry have similarities, it is important for us to recognize the key differences to better describe the interpersonal behaviors we experience. Each of us can consider how people think, feel and respond to a perceived threat to a relationship. Although much reference is made to the “green-eyed monster” of jealousy in romantic relationships, it can also occur with friends, siblings, co-workers, and other people in our daily lives. Jealousy can be triggered by events, such as thinking your partner is flirting with someone attractive, but it can occur even in the absence of an actual rival. How we experience jealousy can be influenced by a variety of factors, including our personality, culture, and the unique characteristics of the relationship.

As with other aspects of the dark side of communication, jealousy can serve both negative and positive functions in relationships. Previous research has suggested that jealousy is related to six interpersonal communication functions: preserving self-esteem, maintaining (protecting) the relationship, reducing uncertainty about both the primary and rival relationship, restoring balance in the relationship, and reassessing the relationship (Guerrero & Anderson, 1996). One potentially positive outcome of jealousy is that it can motivate people to take steps to improve their relationship (Henniger & Harris, 2014), such as investing time and effort in the relationship. Nonetheless, jealousy has been linked to relationship dissatisfaction and increases in deception and relationship violence (Elphinston, et al., 2013; Guerrero, et al., 2005).

Types of Jealousy

Jealousy can show itself in different forms, including cognitive, behavioral, or emotional jealousy (Guerrero & Andersen, 1998). Cognitive jealousy occurs when you experience negative thoughts about your partner’s behavior or a third party whom you believe is interfering in your relationship. For example, if someone starts texting your partner late at night, sending pictures and flirtatious messages, you may find yourself questioning the other person’s motives. Emotional jealousy refers to the emotions that are mixed in with your jealous experience, such as hurt, anger, and fear. Lastly, behavioral jealousy occurs when you take steps to monitor your partner, such as checking their phone, tracking their location, or trying to limit and/or control who they associate with.

Responding to Jealousy

What is the best way to manage feelings of jealousy when they arise? Research has shown that using a “self-reliance” strategy may work the best (Salovey & Rodin, 1988). This approach calls for you to acknowledge your feelings while not letting the triggering event derail you from what you were doing. Furthermore, research suggests that following up the triggering event with calm discussions about jealous feelings (e.g., disclosure) and demonstrating increased affection toward partners lead to the most positive outcomes in these situations (Kennedy-Lightsey, 2018).

Conclusion

In this chapter, we have covered the history of the dark side of interpersonal communication, defining the dark side today, and three interpersonal behaviors typically described as “dark”: deception, gaslighting, and jealousy. Through this introduction to the dark side, we have provided each of you with a more nuanced look at interpersonal communication and how it manifests across our relationships. Upon concluding this chapter, it is our hope that each of us leaves with a better understanding of how our interpersonal communication behaviors are functionally ambivalent, allowing for us to better evaluate destructive and productive elements of our interpersonal behaviors in various relationships.

References

Altman, I., & Taylor, D. A. (1973). Social penetration: The development of interpersonal relationships. Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Berscheid, E., & Walster, E. (1974). Physical attractiveness. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 7, 157-215. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60037-4

Bevan, J. L. (2013). The communication of jealousy. Peter Lang.

Buller, D. B. & Burgoon, J. K. (2006). Interpersonal deception theory. Communication Theory, 6(3), 203-242. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.1996.tb00127.x

Cupach, W. R., & Spitzberg, B. H. (1994). The dark side of interpersonal communication. Laurence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Dillow, M. R. (2023). An introduction to the dark side of interpersonal communication. Cognella.

Elphinston, R. A., Feeney, J. A., Noller, P., Connor, J. P., & Fitzgerald, J. (2013). Romantic jealousy and relationship satisfaction: The costs of rumination. Western Journal of Communication,77(3), 293-304. https://doi.org/10.1080/10570314.2013.770161

Graves, C. G., & Spencer, L. G. (2022). Rethinking the rhetorical epistemics of gaslighting. Communication Theory, 32(1), 48-67. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtab013

Guerrero, L. K., & Andersen, P. A. (1996). Jealousy experience and expression in romantic relationships. In P. A. Anderson & L. K. Guerrero (Eds.), Handbook of

Guerrero, L. K., Trost, M. R., & Yoshimura, S. M. (2005). Romantic jealousy: Emotions and communicative responses. Personal Relationships, 12(2), 233-252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1350-4126.2005.00113.x

Henniger, N. E., & Harris, C. R. (2014). Can negative social emotions have positive consequences?: An examination of embarrassment, shame, guilt, jealousy, and envy. In W. G. Parrott (Ed.), the positive side of negative emotions (pp. 76-97). The Guilford Press.

Kennedy-Lightsey, C. D. (2018). Cognitive jealousy and constructive communication: The role of perceived partner maintenance and uncertainty. Communication Reports, 31(2), 115-129. https://doi.org/10.1080/08934215.2017.1423094

Parks, M. R. (1982). Ideology in interpersonal communication: Off the couch and into the world. In M. Burgoon (Ed.), Communication yearbook 5. Transaction Books.

Petronio, S. (2002). Boundaries of privacy: Dialectics of disclosure. State University of New York Press.

Salovey, P., & Rodin, J. (1988). Coping with envy and jealousy. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 7(1), 15-33. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1521/jscp.1988.7.1.15

Spitzberg, B. H., & Cupach, W. R. (1998). The dark side of close relationships. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Spitzberg, B. H., & Cupach, W. R. (2007). The dark side of interpersonal communication (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Zuckerman, M., DePaulo, B. M., & Rosenthal, R. (1981). Verbal and nonverbal communication of deception. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 14, 1-59. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60369-X

This chapter contains sections from the following material:

“Interpersonal Communication: Context and Connection-OERI” licensed CC BY-SA.