10 Chapter 10 – Family Relationships

Definitions, Patterns, and Family as a System

Robert D. Hall, PhD

Introduction

Michael has always considered his family “abnormal.” When he was five, he was adopted by his adoptive parents, Jim and Tammy. However, when Michael was 10, Jim and Tammy divorced. Jim later remarried to Stephanie, becoming Michael’s stepmother. Additionally, Stephanie had two daughters and a son, giving Michael three stepsiblings. Still, Michael preferred to live with Tammy and spent most of his time at her house growing up. In a way, Michael felt closer to being a member of a single-parent household than a stepfamily. Even though he has stepsiblings, Michael actually considers his friend, Jeff, to be more like a brother given how often he and Jeff support and talk with one another. Through Michael’s experiences, some of us may relate as we come to understand the complexity of families and how they communicate. Thus, in this chapter we will explore the idea of family, family communication, and introduce some of the ways our families communicate. To start, we will first explore the key question of: “What is family?”

10.1 What is Family?

A nearly universal aspect of the human condition is that people have families. Even when mentioning the word, “family,” many of us may envision our family-of-origin, or those people who raised us. Yet, if we were to ask our friends, coworkers, and classmates who makes up our families, we would rarely find people with identical family behaviors and structures. Because of this, there is no single definition of the word “family” that is agreed upon across family disciplines. Our families are a dynamic, ever changing group of individuals working together to navigate the world. However, there are some common ways we view families, and we use three lenses to describe the main types of families: biogenetic, sociolegal, and role.

Biogenetic Family Lens

If you have ever heard the phrase, “blood is thicker than water,” when describing family, you have heard the biogenetic lens in action. The biogenetic lens of family considers two main criteria: whether the relationship is directly or potentially able to reproduce or whether the relationship shares genetic material (Braithwaite et al., 2019). So long as a family relationship is a heterosexual spousal relationship capable of reproducing or we share “blood” (i.e., genetics) with another, we would consider that person as “family” based on these two criteria alone. In Michael’s family from the introduction, he likely would not have considered his family to be biogenetic as he lacked shared genetic material with his parents. In the United States, the biogenetic family lens is the dominant lens for how we view family (Scharp & Thomas, 2016). Many of our customs and laws are centered around the idea of biogenetic family. For example, if an individual dies without a will, in many cases the person who is “next of kin,” or the individual’s closest living blood relative (note: some jurisdictions do include spouses or adopted family members as “next of kin,” Legal Information Institute, n.d.) will automatically receive any last rights of the individual (e.g., burial and funeral planning, finances). Additionally, when claiming parental rights, Utah State Law privileges the biogenetic family lens, stating “it is in the best interest and welfare of a child to be raised under the care and supervision of the child’s natural parents,” asserting that, “a child’s need for a normal family life in a permanent home, and for positive, nurturing relationships is usually best met by the child’s natural parents” (Utah Code 80-2a-201.1.c). All-in-all, we consider the biogenetic family as the dominant perspective of family in the United States given its pervasiveness through various aspects of culture and its precedence in defining how families in the United States should function (Scharp & Thomas, 2016). However, the biogenetic lens is not the only lens through which we can view family as other lenses may account for more diverse family types.

Sociolegal Family Lens

As opposed to considering an individual’s family simply by their ability to reproduce or whether they share genetic material, the sociolegal lens of family relies “on the enactment of laws and regulations to define family relationships and formally sanction them into law” (Braithwaite et al., 2019, p. 7). Here, it is important to note that some of our legislation and regulations, like those mentioned at the end of the previous paragraph, invoke the biogenetic lens into the sociolegal lens. However, other family relationships are further governed by legislation and regulations like adoptive families, foster families, same-sex marriage families, and stepfamilies among others. When considering the sociolegal lens, these familial relationships are exclusively defined by their legal standing as they often lack at least one biogenetic tie. In Michael’s family from the opening scenario, he was adopted by Jim and Tammy, demonstrating a sociolegal tie. Additionally, his father remarried, putting him in another sociolegal family relationship with his stepmother and stepsiblings. Thus, although the biogenetic family is the dominant perspective of family in the United States, the sociolegal family would be considered the next level down in the United States given its formality through legislation and regulation. Still, the biogenetic and sociolegal family lenses don’t account for all family types.

Role Family Lens

The final lens of family discussed in this chapter is the role lens through which “we consider people family when they act and feel like family,” using social behavior and emotion as the key aspects to define family (Briathwaite et al., 2019, p. 7). Basically, anytime someone feels “like family,” the role lens would consider those individuals to be have a familial relationship. In Michael’s case, his friend, Jeff, felt “like a brother” despite having no biogenetic or sociolegal ties. Jeff acted like family, so Michael considered him to be family using the role lens. The role lens is the most marginalized family lens, which is perhaps not surprising given the dominance of the biogenetic and sociolegal lenses in United States culture. However, it is a lens in which communication scholars are particularly interested in studying given how much the role lens relies on communication (Braithwaite et al., 2019). Thus, now that we have considered the three main lenses of family, we can form our definition of family.

Defining Family

As stated earlier, a single definition of family does not exist. Given the complexity and various lenses of family, it is not surprising to know that scholars struggle to come up with a universal definition. However, Braithwaite et al. (2019) do a solid job at providing a general definition of family that considers all three lenses of family we have discussed thus far. Braithwaite and her colleagues (2019) define family as “networks of people who share their lives over long periods of time, bound by ties of marriage, blood, law, commitment, legal or otherwise, who consider themselves as family and who share a significant history and anticipated future functioning as family” (p. 8). In this definition, the authors show that family doesn’t just come from nowhere–it takes a “long period of time” to become a family and families “share a significant history.” Additionally, the authors acknowledge that family can be biogenetic, sociolegal, or role based. The authors make a final claim that family exists beyond the past and the present as family is expected to have a future together in some way, shape or form. Now that we have provided an introductory answer to the question, “What is Family?” we will next discuss the question of, “What is family communication?”

Statistical Definition of ‘Family’ Unchanged Since 1930

By David Pemberton (2015, January 28)

What is the Census Bureau’s definition of “family”?

Printed decennial census reports from 1930 to the present are consistent in their definition of “family.” The 2010 version states: “A family consists of a householder and one or more other people living in the same household who are related to the householder by birth, marriage or adoption.”

The 1930 version is strikingly similar: “Persons related in any way to the head of the family by blood, marriage or adoption are counted as members of the family.”

But prior to 1930, the definition of a family was quite different.

The 1920 version went like this: “The term ‘family’ as here used signifies a group of persons, whether related by blood or not, who live together as one household, usually sharing the same table. One person living alone is counted as a family, and, on the other hand, the occupants or inmates of a hotel or institution, however numerous, are treated as a single family.”

The 1900 Census announced: “The word family has a much wider application, as used for census purposes, than it has in ordinary speech. As a census term, it may stand for a group of individuals who occupy jointly a dwelling place or part of a dwelling place or for an individual living alone in any place of abode. All the occupants and employees of a hotel, if they regularly sleep there, make up a single family, because they occupy one dwelling place …”

The older definition is closer to the current use of the term “household.”

Enumerator instructions beginning in at least 1860 and extending at least through 1940 emphasize this older definition of family.

Here is an example from the 1860 instructions: “By the term ‘family’ is meant either one person living separately and alone in a house, or a part of a house, and providing for him or herself, or several persons living together in a house, or part of a house, upon one common means of support and separately from others in similar circumstances. A widow living alone and separately providing for herself, or 200 individuals living together and provided for by a common head, should each be numbered as one family.”

The 1870 instructions add the element of eating together as one defining element of a family: “Under whatever circumstances, and in whatever numbers, people live together under one roof, and are provided for at a common table, there is a family in the meaning of the law.”

By 1930, the concept of a “household” had become more important and by implication was separated from the term “family”: “A household for census purposes is a family or any other group of persons, whether or not related by blood or marriage, living together with common housekeeping arrangements in the same living quarters.”

In 1960, the concepts of household and family were even more clearly delineated: “A household consists of a group of people who sleep in the same dwelling unit and usually have common arrangements for the preparation and consumption of food. Most households consist of a related family group. In some cases, you may find three generations represented in one household. Some household members may have no family relationship to the central group — boarders and servants, for example — but they should be included with the household if they eat and sleep in the same dwelling unit.”

In summary, the definition of family before 1930 was more similar to today’s definition of household. However, since 1930, the definition of family has remained the same, and includes those who are related to the householder by birth, marriage, or adoption.

10.2 What is Family Communication?

If something like family is so hard to define, how can we be expected to provide a definition for family communication? This question eludes family communication scholars to this day, but one thing that most family communication scholars agree on is that family is constituted, or created, through communication (Baxter, 2013; Braithwaite et al., 2019). In other words, without communication, a family cannot exist. Through this perspective, we come to know that families are discourse dependent, or reliant on communication processes that build and sustain family identity (Galvin, 2006). Here, it is important to note that some families are more discourse dependent than others. As Thompson et al. (2022) noted, families who have cultural representations of family “already built for them” differ from those “who must erect their own.” For example, a heterosexual family with one or more biological children has more cultural models for how to do family than a homosexual couple with one or more adoptive children (Dixon, 2018). To further exemplify, Galvin (2006) provided internal boundary management strategies and external boundary management strategies to demonstrate how discourse dependence helps build family identity.

Internal Boundary Management Strategies

Discourse dependent families utilize internal boundary management strategies, meaning they occur within the family, to create and negotiate their family identity. One such strategy is referred to as naming. Naming occurs when we indicate our familial status or connection with another family member (Braithwaite et al., 2019). For more dominant family structures (e.g., heterosexual spouses with one or more biological children), it seems “natural” to call the parental figures “mom” or “dad.” However, this is not as “natural” as it is invoking the dominant cultural standards for these types of families. Compare this with families who have homosexual spouses with adoptive children. Immediately, we can recognize that this family structure doesn’t have a clear-cut cultural model. In fact, research has shown that families with adoptive children often explicitly discuss what name to call the parental figures, called address terms (Kranstuber Horstman et al., 2018). Thus, while dominant family structures tend to have the discourse already built for them, other families are more dependent on discourse to make sense of their relationships because of the lack of well-developed cultural models (Braithwaite et al., 2019). However, families don’t exist in isolation–they interact with the social world that surrounds their life.

External Boundary Management Strategies

Discourse dependent families also utilize external boundary management strategies, meaning they occur with those not a part of the family, to create and negotiate their family identity. One such strategy is referred to as labeling. Labeling is similar to naming in that it indicates our familial status or connection, but it does so more to provide an orientation to a situation for those outside of the family unit (Braithwaite et al., 2019). For more dominant family structures, many children would not second guess a friend referring to their parents as “mom” and “dad.” However, discourse dependent families may use similar address terms to help others understand their family identity. For example, one of the author’s former students had a stepfather. The student explained that she would sometimes be asked how she refers to her stepfather. She would tell those people that she calls him “dad” because he acted more like a father to her than her biological father did. in this way, we can see how some discourse dependent families use the terms of the dominant culture to make sense of their own family identity, especially when interacting with those outside of the family structure. Now that we’ve defined family and family communication through discourse dependence, we will next discuss communication patterns of families.

10.3 Family Communication Patterns

One of the more prominent theories in the field of family communication is Koerner and Fitzpatrick’s (2006) family communication patterns theory (FCP). Theorists who utilize FCP to study families do so “to explain how family members develop a shared social reality through communication” considering “perceptions of agreement in attitudes, beliefs, and values” (Braithwaite et al., 2019, p. 59-60). According to Koerner et al. (2018), parent-child interactions are pivotal in developing our schemas, or mental interpretations of the social world, for interaction both within and outside of the family.

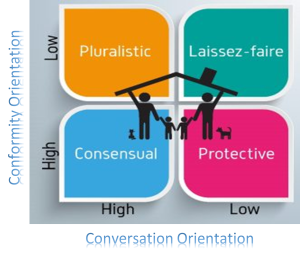

These schemas are considered along two orientations within FCP: conformity and conversation. The conformity orientation “refers to the degree to which family communication stresses a climate of homogeneity of beliefs, values, and attitudes” (Braithwaite et al., 2019, p. 60). In other words, families that are higher in the conformity orientation are more likely to be expected to follow similar belief structures and hold similar family values. However, those that are lower in the conformity orientation are more likely to be accepting of different belief structures and differing family values. The conversation orientation “references the degree to which all family members are encouraged to participate in unrestrained interaction about a wide range of topics” (Braithwaite et al., 2019, p.60). In other words, families that are higher in the conversation orientation are likely to have open discussions about many different ideas, perspectives, and worldviews. Families that are lower in the conversation orientation are more likely to have closed discussions with little talk about different ideas, perspectives, and worldviews. Within FCP, there are four different family typologies which we will cover next: consensual, protective, pluralistic, and laissez-faire (see figure 1). First, we will cover consensual families.

Consensual

For FCP theorists, consensual families are those that are high in conformity and high in conversation. Consensual families demonstrate a tension between adhering to parental authority and working to have open dialogue and explore new ideas together among all family members (Braithwaite et al., 2019). One way in which a consensual family may enact these ideas are for the parents to allow the children to have input on decision-making, but the parents have the final say. For example, Diego’s parents are considering buying a new television for the living room. Rather than the parents going out and buying one without telling the children, the parents decide to bring the topic up over dinner. The parents ask Diego and his siblings’ input on what kind of television to get. In the end, the parents will ultimately make the decision on which television to purchase, but Diego’s parents allowed for open dialogue and exploring options together with the children of the family. However, not all families engage in such open dialogue around family decision-making.

Protective

Protective families are families that are high in conformity, but low in conversation. Protective families tend to place “an emphasis to parental authority and…little to no concern for open communication among family members” (Braithwaite et al., 2019, p. 61). Such families would expect children to adhere to the parents’ decision-making and family values. For example, Kendra wants her children to attend church with her and her husband, Donovan, every Sunday. There is no discussion over where they will attend the service, and Kendra’s children can expect punishment if they object to attending the service as a family. In this way, we see that Kendra’s family is protective given that any differing ideas are shut down with respect to parental authority. However, while some families emphasize parental authority, others may emphasize family discussion.

Pluralistic

Some families are considered pluralistic families who are low in conformity and high in conversation. For pluralistic families, the parents feel little need to be in control and there are open discussions that have no restraints regarding topic and include all family members (Koerner & Schrodt, 2015). In one of the author’s families growing up, his parents expected the dinner table to be a place where politics was never discussed. Imagine this author’s surprise when he joined one of his friend’s family for dinner one night. At this dinner, the family discussed politics, religion, and sexuality within the span of one hour. No one was shut out of the discussion, and everyone seemed to have an equally held perspective on these topics despite the differing opinions. This family demonstrated a pluralistic family at this dinner given the unrestrained conversation and no conformity to any parental authority during this interaction. While some families may have unrestrained conversation, others may have little to no conversation at all.

Laissez-faire

Laissez-faire families are characterized by low conformity and low conversation. Families who are laissez-faire (roughly meaning “let it happen” in French) tend to have little conversation, and when they do the topics are limited. Additionally, those in laissez-faire families are relatively uninvolved in each other’s lives (Koerner & Schrodt, 2015). Many members of laissez-faire families tend to have little emotional attachment with their family and children tend to seek social support from outside influences like friends (Braithwaite et al., 2019). We may consider Michael’s family from the introduction more laissez-faire. Michael already has little interaction with his adopted father, and he doesn’t receive much social support from his adopted mother. He doesn’t really have an emotional attachment with his stepparents or stepsiblings either. Thus, Michael has formed a brother-like connection with his friend, Jeff, from whom he receives a lot of his social support.

Figure 1

Additional Thoughts on Family Communication Patterns Theory

As we consider FCP an important way to organize families into various typologies, we find it important to offer a couple of important considerations regarding the way FCP presents the various communication patterns. First, it is important to note that an “ideal” type of family does not exist. At first glance, it may seem like the protective family communication pattern is too strict and limits children’s ability to find their own voice. However, Hesse et al. (2017) proposed the idea of warm conformity in which families emphasize consistency with rules, sharing beliefs regarding openness and equality, set family time together, and uphold a value of close family relationships. The concept of warm conformity thus counters what we may consider the more cold conformity that comes to mind in the original description of protective families emphasizing parental authority and strictly adhering to family values. Second, FCP may initially come across as prescriptive, leaving little “wiggle room” for differences and variables such as time. However, it is important to note that family communication patterns are more of a state instead of a trait. Communication, after all, is a skill. Thus, our family communication patterns can, and do, change over time and as families undergo transitions, or “changes in identities, roles, routines, or circumstances that may occur at the individual, dyadic, or situational level” which leads to changes in how families interact with one another (Dillow, 2023, p. 23).

10.4 Family Systems Theory

Systems theory is an interdisciplinary theory that discusses how things are related to one another. Originally developed by Bertalanffy (1968), he defined a system as “sets of elements standing in interrelation” (p. 38). Although originally conceptualized in organizations, Bowen (1978) extended systems theory to be applied in family contexts. Over the years, numerous researchers have furthered the basic ideas of Bertalanffy and Bowen, to further our understanding of family systems. Part of this process has been identifying different characteristics of family systems. According to Galvin et al. (2006) there are seven essential characteristics of family systems, of which we will cover each: interdependence, wholeness, patterns/regularities, interactive complexity, openness, complex relationships, and equifinality. We will start with discussing interdependence.

Interdependence

The term interdependence means that changes in one part of the system affects other parts of the system. In other words, “what I do affects the others in the system.” For example, if one of the gears in a watch gets bent, the gear will affect the rest of the watch’s ability to tell time. In this idea, the behaviors of one family member will impact the behaviors of other family members. To combine this idea with family communication patterns described earlier, parents/guardians that are high in conversation orientation and low in conversation orientation will impact that children’s willingness and openness to communicate about issues of disagreement.

On the larger issue of pathology, numerous diseases and addictions can impact how people behave and interact. If a family has a child diagnosed with cancer, the focus of the entire family may shift to the care of that one child. If the parents/guardians rally the family in support, this diagnosis could bring everyone together. On the other hand, it’s also possible that the complete focus of the parents/guardians turns to the ill child and the other children could feel unattended to, which could lead to feelings of isolation, jealousy, and resentment.

Wholeness

The idea of wholeness is the ability to see behaviors and outcomes within the context of the system. To understand how a watch tells time, we cannot just look at the fork pin’s activity and understand the concept of time. In the same way, examining a single fight between two siblings cannot completely tell us everything we need to know about how that family interacts or how that fight came to happen. How siblings interact with one another can be manifestations of how they have observed their parents/guardians handle conflict or even extended family members like aunts/uncles, grandparents, and cousins.

Wholeness is often discussed in opposite to reductionism. Reductionists believe that the best way to understand someone’s communicative behavior is to break it down into the simplest parts that make up the system. For example, if a teenager exhibits verbal aggression, a reductionist would explain the verbally aggressive behavior in terms of hormones (specifically testosterone and serotonin). Holistic systems thinkers don’t negate the different parts of the system, but rather like to take a larger view of everything that led to the verbally aggressive behavior. For example, does the teenager mirror their family’s verbally aggressive tendencies? Basically, what other parts of the system are at play when examining a single behavioral outcome?

Patterns/Regularities

Families like balance and predictability. To help with balance and predictability, systems (including family systems) create a complex series of both rules and norms. In a family system, rules can be defined as “relationship agreements that prescribe and limit a family’s behavior over time” (Braithwaite et al., 2019, p. 112). For example, a child may grow up hearing, “children are to be seen and not heard.” This rule dictates that in social situations, children are not supposed to make noise or actively communicate with others. Norms, on the other hand, are patterns of behavior that are arrived at through the interactions in system. For example, maybe the mother in a family has a home office, and everyone knows that when she is in her office, she should not be disturbed.

Of course, one of the problems with patterns and regularities is that they become deeply entrenched and are not able to be changed or corrected quickly or easily. When a family is suddenly faced with a crisis event, these patterns and regularities may prevent the family from actively correcting the course. For example, imagine living in a family where everyone is taught not to talk about the family’s problems with anyone outside the family. If one of the family members starts having problems, the family may ultimately not get the help it needs to function effectively.

Interactive Complexity

The notion of interactive complexity stems back to the original work conducted by Bowen (1978) on family systems theory. In his initial research looking at individuals with schizophrenia, a lot of families labeled the schizophrenic as “the problem” or “the patient,” which allowed them to put the blame for family problems and interactions on the schizophrenic individual. Instead, Bowen realized that schizophrenia was one person’s diagnosis in a family system where there were usually multiple issues going on. Trying to reduce everything down to the one label, essentially letting everyone else “off the hook” for any blame for family problems, was not an accurate portrayal of the family.

Instead, it’s important to think about interactions as complex and stemming from the system itself. For example, all married couples will have disagreements. Some married couples take these disagreements, and they become highly contentious fights. These fights are often repetitious and seen over and over again. Mary asks Anne to take out the trash. The next day, Mary sees that the trash hasn’t been taken out yet. Mary turns to Anne at breakfast and says, “Are you ever going to take out the trash?” Anne quickly replies, “Stop nagging me already. I’ll get it done when I get it done.” Before too long, this becomes a fight about Anne not listening to Mary from Mary’s point-of-view, while the conversation becomes about Mary’s constant nagging from Anne’s point-of-view. Before long, the argument devolves into an argument about who started the conflict in the first place. Galvin et al. (2006) argue that trying to determine who started the conflict is not appropriate from a systems perspective, but instead, researchers should focus on which “current patterns serve to uncover ongoing complex issues” (p. 313).

Openness

The next major characteristic of systems is openness. The term openness refers to how permissive system boundaries are to their external environment. For family systems, openness refers to how much families are influenced by their external environment, which could bring about change in family functioning (Braithwaite et al., 2019). Some families have fairly open boundaries. In essence, these families allow for a constant inflow of information from the external environment and outflow of information to the external environment. Other families are considerably more rigid about system boundaries. For example, maybe a family is deeply religious and does not allow television in the home. Furthermore, the family only allows reading materials that come strictly from their religious sect and actively prevent any ideas that may threaten their religious ideology. In this case, the family has a very rigid and closed boundary. When families close themselves off from the external environment, they essentially isolate themselves. Children who are reared in highly isolated family systems often have problems interacting with other children when they come into contact with them in the external environment (like school), demonstrating potential negative effects of the cold conformity discussed earlier in FCP.

Complex Relationships

Systems do not exist in isolation, but rather “are embedded in larger systems, creating a highly complex set of structures and interaction patterns that may only be understood in relational to each other” (Braithwaite et al., 2019, p. 14). Thus, it’s important to remember that all family systems also have multiple subsystems. One of the areas that Bowen (1978) became very interested in was how family subsystems develop and function during times of crisis. In Bowen’s view, a couple may be the basic unit within an emotional relationship. Still, any tension between the couple will usually result in one or both parties turning to others. If there are not others within the family itself, partners will bring in external people into the instability. For example, James and Ralph just got married. After a recent argument, Ralph ended up talking to his best friend, Shelly, about the argument. Bowen (1978) argued a two-person system under stress will draw in a third party to provide balance, which ultimately creates a two-helping-one or a two-against-one dynamic. It’s also possible that James decides to talk to his mother, Polly, which creates a different triangle. Here, we see the family system comprised of smaller, relational subsystems creating complex relationships varying in dynamics and power.

Equifinality

The final characteristic of family systems is equifinality. Equifinality is defined as the ability to get to the same end result using multiple starting points and paths. For family systems, this means that there is no single “right way” of doing or being a family. Going back to the basic definition of “family” discussed earlier in this chapter, there are many different ways for people to form relationships that are called families. Within family systems theory, the goal is to see how different family systems achieve the same outcomes (whether positive or negative).

Conclusion

In this chapter, we have discussed the fundamentals of family communication. We began with a discussion of family, explored how to conceptualize family communication, introduced family communication patterns, and finished with a discussion of the family as a system. In this chapter, we have come to understand that family, although a universal experience of the human condition, varies so much from person-to-person. In this way, it is our hope that we leave with a more nuanced understanding in responding to the question, “What is family?”

References

Bertalanffy, L. von. (1968). General systems theory. George Braziller.

Bowen, M. (1978). Family therapy in clinical practice. Aronson.

Dillow, M. R. (2023). An introduction to the dark side of interpersonal communication. Cognella.

Galvin, K. M. (2006). Diversity’s impact on defining the family: Discourse-dependence and identity. In L. H. Turner & R. West (Eds.), The family communication sourcebook (pp. 3-19). Sage.

Galvin, K. M., Braithwaite, D. O., Schrodt, P., & Bylund, C. L. (2019). Family communication: Cohesion and change (10th ed.). Routledge.

Galvin, K. M., Dickson, F. C., & Marrow, S. F. (2006). Systems theory: Patterns and (w)holes in family communication. In D. O. Braithwaite & L. A. Baxter, Engaging theories in family communication: Multiple perspectives (pp. 309-324). Sage.

Hesse, C., Rauscher, E. A., Goodman, R. B., & Couvrette, M. A. (2017). Reconceptualizing the role of conformity behaviors in family communication patterns theory. Journal of Family Communication, 17(4), 319-337. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2017.1347568

Koerner, A. F., & Fitzpatrick, M. A. (2006). Family communication patterns theory: A social cognitive approach. In D. O. Braithwaite & L. A. Baxter (Eds.), Engaging theories in family communication: Multiple perspectives (pp. 50-65). Sage.

Koerner, A. F., & Schrodt, P. (2014). An introduction to the special issue on family communication patterns theory. Journal of Family Communication, 14(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2013.857328

Koerner, A. F., Schrodt, P., & Fitzpatrick, M. A. (2018). Family communication patterns theory: A grand theory of family communication. In D. O. Braithwaite, E. A. Suter, & K. Floyd (Eds.), Engaging theories in family communication: Multiple perspectives (2nd ed., pp. 142-153). Routledge.

Kranstuber Horstman, H., Colaner, C. W., Nelson, L. R., Bish, A., & Hays, A. (2018). Communicatively constructing birth family relationships in open adoptive families: Naming, connecting, and relational functioning. Journal of Family Communication, 18(2), 138-152. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2018.1429444

Legal Information Institute. (n. d.). Next of kin. Retrieved from https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/next_of_kin

Scharp, K. M., & Thomas, L. J. (2016). Family “bonds”: Making meaning of parent-child relationships in estrangement narratives. Journal of Family Communication, 16(1), 32-50. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2015.1111215

Utah Code 80-2a-201.1.c

This chapter includes sections from the following material:

“Interpersonal Communication: A Mindful Approach to Relationships” licensed CC BY-NC-SA.