7 Measurement

Once a researcher has identified a research question and chosen an appropriate research method, they must determine how they will measure the social phenomena that are the focus of their research question. Measurement refers to the process of describing and ascribing meaning to key facts, concepts, or other phenomena under investigation. At its core, measurement is about defining one’s terms clearly and accurately. Some constructs in social science research, such as a person’s age or the number of people in prison, may be easy to measure. Other constructs such as creativity, prejudice, or alienation are considerably harder to measure. For these reasons, measurement in social science isn’t quite as simple as using some predetermined or universally agreed-upon tool. But no matter the topic, researchers must always think carefully and deliberately about how to measure the central components of their research questions. This chapter focuses on two key processes involved in empirical measurement: conceptualization and operationalization.

How Do Social Scientists Measure?

Measurement occurs at multiple stages of a research project, including planning, data collection, and sometimes even data analysis. A researcher begins the measurement process by describing the key ideas they hope to investigate, usually stated in the research question. For instance, let’s say our research question is: “How do lawyers with different family backgrounds cope with the emotional demands of their job?” Answering this question requires some idea about what coping means. We may come up with an idea about what coping means as we begin to think about what to look for (or observe) during data collection. Once we’ve collected data on coping, we have to decide how to report on the topic. Perhaps, for example, there are different types or dimensions of coping, some of which lead to more successful emotional outcomes than others. The decisions we make about how to proceed and what to report will involve processes of measurement.

Measurement is a process, partly because it occurs at multiple stages of conducting research. We could also think of measurement as a process because measurement in itself involves multiple stages such as identifying key terms, defining them, figuring out how to observe them, and assessing whether our observations are any good. The next two sections cover two important steps in the measurement process: conceptualization and operationalization.

Conceptualization

A concept is a notion or image conjured when we think of some cluster of related observations or ideas. For example, what do you think of when you hear “family background”? Perhaps you think of ideas associated with “socioeconomic status” (SES). When you hear that phrase, you might think of how much money a person makes, their wealth and assets, or how they dress or behave. Of course, everyone conjures up somewhat different ideas or images when they hear the term “socioeconomic status,” and we may struggle if asked to define exactly what the term means. In fact, there are many possible ways to define the term. While some definitions may be more common or have more support than others, there isn’t one true, always-correct-in-all-settings definition. Definitions of SES may shift over time, from culture to culture, and from individual to individual. Without understanding how a researcher has defined key concepts, it would be nearly impossible to understand the meaning of that researcher’s findings and conclusions. Thus, the process of measurement includes defining concepts, also called conceptualization.

Conceptualization is the process of defining fuzzy concepts and their constituent components in concrete and precise terms. Going back to our example of “socioeconomic status,” if someone buys a yacht, are they in a different socioeconomic status than a person who buys a fishing boat? If a person has a retirement account, does that indicate their socioeconomic status? Does it matter how much they have in that account? What if they have multiple accounts? What about owning a company, having a GED, or having enough money to work only part-time? Are there different ways to be in the same socioeconomic status? At what point does a family move between statuses? Answering these kinds of questions is the key to clearly defining concepts because the answers help us understand what is included and excluded from the concept we’re trying to measure.

Asking questions, brainstorming images, and playing around with possible definitions is a reasonable start to the conceptualization process. During this process, researchers also consult with previous research and theories to understand how other scholars have already defined the concepts in question. However, this doesn’t necessarily mean researchers use pre-existing definitions. Understanding how concepts have been defined in the past gives us ideas about how our conceptualizations compare with the predominant definitions in our field. Understanding prior definitions of key concepts also helps us decide whether our research will challenge existing conceptualizations or rely on them for our own work.

The conceptualization process is all the more important because of the imprecision, vagueness, and ambiguity of many social science concepts. For instance, is “socioeconomic status” the same thing as “income” or “wealth”? Imagine a researcher proposing that “Lawyers in higher socioeconomic statuses use less effective coping strategies to deal with the emotional demands of their job.” The researcher cannot test this proposition unless they first conceptually separate socioeconomic statuses. For example, being in a higher SES might entail having a position of power in a society, or a specific worldview of oneself or one’s family as superior to others, both of which are distinct from being in a lower SES, which might entail working for others or defining oneself as “middle class”. The point is that definitions of such concepts are not based on an objective criterion, but rather on shared (“inter-subjective”) understandings of what these ideas mean. Thus, researchers must clearly state how they will define their key concepts so that others can understand and assess the findings and implications of the research study. Given the preceding discussion, how would you define SES? Your answer is your conceptualization of SES.

Operationalization

Once a researcher has defined or conceptualized a concept, how do they measure it? Operationalization refers to the process of explaining precisely how a concept will be measured. Operationalization works by identifying specific indicators, or empirical observations taken to represent the ideas we are interested in studying. Social scientists tend to measure most concepts using multiple indicators. For instance, if an unobservable concept such as SES is defined as the level of family income, it can be operationalized using an indicator that asks respondents to report their annual family income. However, if a researcher defines SES as a combination of elements including income, level of education, assets, and occupation, it would be measured with multiple questions covering each. Researchers using field research and other methodologies must also operationalize their concepts. For example, a researcher observing lawyers’ courtroom interactions might develop indicators of SES such as clothing styles, mannerisms, or speech patterns. No matter what methodology a researcher chooses, they must always operationalize their concepts during the measurement process.

The process of coming up with indicators must not be too arbitrary or casual. Researchers can avoid taking an overly casual approach to identifying indicators by turning to prior theoretical and empirical work in their area. Theories point toward relevant concepts and possible indicators; published empirical studies give specific examples of how others have defined the important concepts in an area, and what indicators they have used. It might make sense to use the same indicators as other researchers have or to develop new indicators that improve upon previous ones. Either way, researchers must know how others before them have conceptualized and operationalized their concepts.

Putting It All Together

Moving from identifying concepts to conceptualizing them, and then operationalizing them, is a matter of increasing specificity. A researcher begins with a general interest, identifies a few concepts that are essential for studying that interest, works to define those concepts, and then explains precisely how they will measure those concepts. The focus becomes narrower as the researcher moves from a general interest to operationalization.

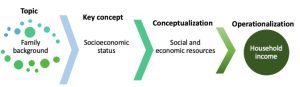

Figure 7.1 illustrates what the process might look like as a researcher moves from a broad level of focus (a topic) to a narrower focus (operationalization) to decide what indicators to use in their study. The figure indicates that the researcher would start with the overall topic (in this case, family background), identify a key concept (e.g., socioeconomic status), define that concept (e.g., social and economic resources), and figure out what indicators would help measure that concept (e.g., household income).

While Figure 7.1 identifies household income as one indicator of SES, the researcher would develop a few more indicators to fully capture the definition of SES as social and economic resources. Other indicators might include those discussed above, such as level of education and speech patterns.

Figure 7.1 makes the measurement process look like a set of linear stages through which a researcher neatly progresses before beginning data collection; however, it doesn’t always work that way, especially in inductive research. For example, imagine a researcher is interested in examining various ways lawyers define SES. They would have already begun the measurement process in the same way as we’ve discussed, by having some general interest and identifying key concepts related to that interest (in this case, SES). They might even have some working definitions of SES, and an idea of how to discover how different lawyers define the concept. But, if the purpose of the study is to discover the variety of indicators lawyers rely on when thinking about SES, then the researcher probably wouldn’t develop a specific set of indicators before beginning data collection.

Thus, rather than defining indicators before collecting data, some researchers focus their projects on collecting data to identify common indicators used by people in the real world, as they try to understand ambiguous, socially constructed concepts.

Variables and Causality

The indicators that a researcher develops to measure abstract concepts pertinent to their study are often called variables. Etymologically speaking, a variable is a quantity that can vary (e.g., from low to high, negative to positive, etc.), in contrast to constants that do not vary (i.e., remain constant). In scientific research, a variable is a measurable representation of an abstract concept. Sometimes, researchers use a group of indicators to create a variable, as might be the case if a researcher decides to measure socioeconomic status using indicators of household income and level of education.

One important piece of the measurement process involves attending to issues of cause and effect, which requires categorizing variables as independent or dependent. Causality refers to the idea that one event, behavior, or belief will result in the occurrence of another, subsequent event, behavior, or belief. In other words, it is about cause and effect. The main criteria for establishing include plausibility, temporality, and spuriousness.

Plausibility means that a claim that one event, behavior, or belief causes another, must make sense. For example, if a researcher observes a series of courtroom interactions during which a prosecutor routinely talks over a defense attorney, the researcher might begin to wonder whether prosecutors who have a propensity to speak loudly are more likely to interrupt other lawyers. However, the fact that there might be a relationship between the volume of a person’s voice and talking over other people does not mean that a prosecutor’s loud voice could cause them to talk over defense attorneys. In other words, just because there might be some correlation between two variables does not mean that a causal relationship between the two is plausible.

The criterion of temporality means that a cause must precede its effect in time. Imagine that our researcher observing lawyers finds that younger lawyers tend to cope with the emotional demands of their jobs by spending more time on social media than older lawyers. In other words, the researcher finds a correlation between age and using social media as a coping strategy. Does this mean that a person’s use of social media determines their age? Definitely not. In addition to being implausible, a person’s age precedes their social media use. Thus, age precedes the use of social media as a coping strategy in time.

Finally, a spurious relationship is one in which an association between two variables appears causal, but can be explained by some third variable. Let’s consider a real-world example of spuriousness. For example, did you know that high rates of ice cream sales have been shown to cause drowning? Of course, that’s not really true, but there is a positive relationship between the two. In this case, a third variable (time of year) causes both high ice cream sales and increased deaths by drowning, because the summer season brings increases in both. In other words, the presence of a third variable explains the apparent relationship between the two original variables.

In sum, the following criteria must be met for a correlation to be considered causal:

- The relationship must be plausible.

- The cause must precede the effect in time.

- The relationship must be nonspurious.

As the above discussion indicates, causality concerns relationships between variables. When one variable causes another, we have what researchers call independent and dependent variables. An independent variable causes another— a dependent variable is caused by another. Dependent variables depend on independent variables. In the example where age was found to be causally linked to social media use as a coping strategy, age would be the independent variable because age caused differences in social media use as a coping strategy. The coping strategy would be the dependent variable because it is caused by age. In other words, using social media as a coping strategy depends on age.

Some research methods, such as those used in qualitative and inductive research, focus on understanding the “how” of causality. These methods contribute to understanding the circumstances under which causal relationships occur. Qualitative, inductive research sometimes relies on quantitative, deductive work to point toward a relationship that may be interesting to investigate further. For example, if a quantitative researcher learns that male lawyers are statistically more likely than lawyers who are women or transgender to use social media as a coping strategy, a qualitative researcher may decide to conduct some in-depth interviews and observations of transgender, men, and women lawyers, to learn more about how the different contexts and circumstances of their lives might shape their respective chances of using social media as a coping strategy. In other words, researchers conducting qualitative, inductive research might work to understand the contexts in which various causes and effects occur.

Summary

- Conceptualization is the process of clearly defining key concepts involved in a research question. It’s one of the first steps in the measurement process after identifying a topic and generating a research question.

- Operationalization occurs after conceptualization, and it is the process of explaining exactly how a concept will be measured.

- The three main criteria for establishing causality include plausibility, temporality, and non-spuriousness.

- Independent variables are those that cause changes in other variables. Dependent variables are those that change due to changes in other variables. Dependent variables depend on independent variables.

Key Terms

| Causality | Independent Variable | Plausibility |

| Concept | Indicators | Spurious Relationship |

| Conceptualization | Measurement | Temporality |

| Dependent Variable | Operationalization | Variable |

Discussion Questions

- Could a researcher skip the conceptualization step of the measurement process? Why or why not?

- Identify a concept that is important in your area of interest. Challenge yourself to conceptualize the term without first consulting prior literature. Then, consult prior work to see how others have conceptualized the concept you chose. How and where does your conceptualization differ from others? What dimensions of the concept hadn’t you or others considered?

- Could a researcher skip the operationalization step of the measurement process? Why or why not?

- Identify a concept that is important in your area of interest. Challenge yourself to identify some possible indicators of that concept without first consulting prior literature. Then, consult prior work to see how others have operationalized the concept you chose. How and where do your indicators differ from others? What types of indicators hadn’t you or others considered?

- Why are each of the three main criteria for establishing causality important? What would happen if one of the three were violated?

- Choose a research question that you’re interested in answering. Then, identify an independent and a dependent variable that would be important for your study. How did you know which variables were independent and dependent?

Media Attributions

- Figure 7. 1 The Measurement Process © Williams, Monica is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license