5 Research Approaches and Goals

Now that you’ve figured out what to study, you need to figure out how to study it. Reading previously published studies and forming a research question are steps in the process of designing a research project. This chapter continues the discussion of research design by examining the major components of a research project, strategies for conducting literature reviews, and the decisions researchers must make when figuring out how to answer their research questions.

Components of a Research Project

Decisions about the various components of a research project do not always occur in sequential order. For example, while researchers review previously published work as they form research questions, they also conduct literature reviews after drafting their questions to become more familiar with how other researchers have investigated their topic. Researchers must also consider potential ethical concerns before and after zeroing in on a specific research question. Literature reviews, research questions, and ethics are all components of research projects, along with research strategies and goals, conceptualization and operationalization, sampling, and data collection methods. Figure 5.1 illustrates how the nine major components of a research project fit together. Rather than steps in a linear process, the concentric circles illustrate that each step occurs in the context of other steps. For example, sampling decisions occur in the context of broader ethical considerations, the research question, and previous research on the topic.

The rest of this textbook focuses on the major components of a research project not yet covered in previous chapters. Chapter 3 discussed ethical concerns and decisions researchers must make as they design and conduct their research. Chapter 4 detailed the process of developing and evaluating research questions, and it provided a brief overview of how to conduct a literature review to find previous studies on your topic. The next section in this chapter provides more detail on conducting literature reviews. Then, we’ll focus on research approaches, ending with a brief overview of two kinds of data researchers collect. Chapter 6 covers conceptualization and operationalization, and Chapter 7 focuses on sampling. Finally, Chapters 8 through 11 detail common methods for collecting and analyzing data.

Literature Reviews (Again)

Chapter 4 presented an overview of how to review previously published work on a particular topic to help form a research question. Once researchers have formed a research question, they return to the literature, to conduct a more comprehensive review of what other researchers have done. At this stage, the purpose of a literature review is three-fold: (1) to survey the current state of knowledge in the area of inquiry, (2) to identify key authors, articles, theories, and findings in that area, and (3) to identify gaps in knowledge in that research area. A well-conducted literature review helps the researcher determine whether prior studies have already answered the initial research (which would eliminate the need to study them again), whether there are newer or more interesting research questions available, and whether the original research questions should be modified or changed in light of findings of the literature review. The review can also provide some intuitions or potential answers to the questions of interest, and help identify methodologies that previous researchers have used to address similar questions. To achieve these three goals, researchers must conduct a reasonably complete search that includes studies published in different journals and years with various methods. Chapter 4 provides information on finding and accessing databases for these types of searches.

Search Strategies

What happens when your search yields few or no results, or if your search results aren’t relevant to your topic or research question? Chances are that you probably need to modify your search terms. For example, imagine you’re working on a research project about sexism in policing. A search on Criminal Justice Abstracts using the keywords “sexism in policing” returns four results. Of the four results, only one is somewhat related to your topic, and it’s about representations of women in police recruiting videos. Does that mean that only one article has been published on your topic? Definitely not. Instead, you’ll need to experiment with different search terms. Since your search yielded so few results, you decided to broaden your search to “gender and policing.” This search yields over 500 results. At first, this may seem like too many articles to sort through; however, a closer look usually indicates that only a few articles on each page will be directly relevant to your research question.

Other strategies for finding articles include narrowing your search terms, locating articles on a similar population or broader topic of interest, and using articles you find to identify other articles. For example, let’s say you started your sexism in policing project by searching for “policing.” That search would yield thousands of results, indicating that your search term needs to be focused on what about policing you’re interested in studying. The “gender and policing” search term is related to your broader topic of interest and you may find articles within those results that relate more specifically to sexism in policing. Once you find a few directly relevant articles, you can use the “cited by” feature of most databases to find recently published articles that cite the articles you’ve found. Some of these may not be related to your research question, but you’ll likely find a few that do. You can also use the bibliography of an article to identify relevant studies published before the article you’ve found.

Reviewing Strategies

Once you’ve identified a set of articles to review, revisit your research question to remind yourself of your specific research focus. Remembering your research interest while reviewing the literature allows you to consider how the theories and findings covered in prior studies might apply to your focus point. For example, theories on what motivates women to get involved in policing might tell you the likely reasons the police officers you plan to study got involved in the profession. At the same time, those theories might not cover the particulars of why women stay in policing, or the sexism they experience once on the job. Thinking about the different theories allows you to focus your research plan, and develop a few hypotheses on your findings.

Researchers often develop an annotated bibliography as they begin to familiarize themselves with prior research on their topic. An annotated bibliography is an alphabetized list of relevant sources, using the citation format of the researcher’s profession and including a summary of the point of focus, theoretical argument, research methods, and major findings. Some annotated bibliographies also contain a critique or evaluation of each source.

Another strategy for reviewing the literature involves a researcher positioning their work within the context of prior scholarly work in the area. This kind of literature review addresses the following questions: What questions have other scholars asked about this topic? What do we already know about this topic? What questions remain? As the researchers answer these questions, they synthesize what they find in the literature, possibly organizing prior studies around themes relevant to their research focus.

The preceding discussion assumes that we all know how to read scholarly literature. Reading scholarly articles can be challenging compared to reading a textbook. Luckily, a few tips can help you navigate these articles. First, scholarly journal articles typically contain many of the same sections. The abstract (the short paragraph at the beginning of an article that summarizes the author’s research question, methods used to answer the question, and key findings) may be the most important and easiest-to-spot section of a journal article. Reading the abstract provides a framework for understanding the research study and findings, which will help determine the relevance of the article to your research question. After the abstract, most journal articles contain the following sections (although exact section names are likely to vary): introduction, literature review, methodology, findings, discussion/conclusion, and a list of references cited. While you should get into the habit of familiarizing yourself with articles you wish to cite in their entirety, there are strategic ways to read journal articles that can make them a little easier to digest. Once you have read the abstract and determined that this is an article you’d like to read in full, read through the discussion section at the end of the article. Reading an article’s discussion section helps you understand what the author views as the study’s major findings, and how the author perceives those findings to relate to other research. If you want more information about the study’s research design, methods, or results, you can locate that information in other sections of the article.

Approaches to Research

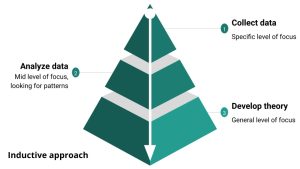

Scientific inquiry may take one of two forms: inductive or deductive. In an inductive research approach, the goal is to infer theoretical concepts and patterns from observed data. Figure 5.2 illustrates the process of research using an inductive approach. As illustrated in the figure, a researcher begins by collecting data relevant to their topic of interest. After collecting a substantial amount of data, the researcher takes a break from data collection and begins looking for patterns in the data, to develop a theory that could explain those patterns. Thus, an inductive research approach involves starting with a set of systematically collected observations (the data) and then moving from those observations to a more general set of propositions about the studied experiences. This approach moves from data to theory, or from the specific to the general. Because of their focus on developing theory, inductive approaches are also called theory-building approaches to research.

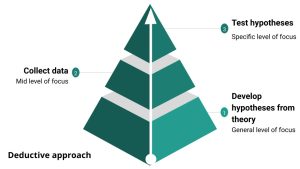

A deductive research approach is the one typically associated with scientific investigation. In a deductive approach, the goal is to use empirical data to test concepts and patterns inferred from theories. The researcher studies what others have done, reads existing theories of whatever phenomenon he or she is studying, and then tests hypotheses that emerge from those theories by collecting and analyzing data. Essentially, researchers move from a general level of focus (theories) to a specific level of focus (hypothesis testing with specific data). Figure 5.3 illustrates a deductive research approach. As illustrated in the figure, a researcher starts with developing hypotheses, or testable statements that propose an explanation for the phenomenon under study, from theories identified in previous literature that may help answer the research question. Deductive approaches can also be called theory-testing because the researcher collects and analyzes data to test their hypotheses. The goal of theory-testing is not only to test a theory, but possibly to refine, improve, and extend it.

Inductive and deductive approaches to research may seem quite different, but theory building (inductive research) and theory testing (deductive research) are critical for advancing scientific knowledge. In fact, the two approaches can be rather complementary. Researchers may plan for their research to include both inductive and deductive components, or they might begin a study with only an inductive or deductive approach but discover they need another approach to help explain their findings.

Rather than opposing strategies for conducting research, it might help to think about inductive and deductive research as two halves of a research cycle that constantly moves between theory and observations. Elegant theories aren’t helpful if they don’t match reality. Likewise, mountains of data are useless until they can contribute to constructing meaningful theories. Rather than viewing these two approaches to research as wholly separate, imagine each iteration between theory and data contributes to stronger theories and explanations of the phenomenon of interest.

Research Goals

One of the first things researchers consider when designing a research project is what they want to accomplish by conducting the research. What do they hope to be able to say about their topic? Do they hope to gain a deep understanding of whatever phenomenon they’re studying, or would they rather have a broad, but perhaps shallower, understanding? Do they want policymakers or others to use their research findings to shape social life, or is the project more about exploring curiosities? The answers to these questions help researchers to decide whether to design their studies as exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory research projects.

Exploration

Researchers conducting exploratory research are often starting in new areas of inquiry where the goals of the research include: (1) scoping out the magnitude or extent of a particular phenomenon, problem, or behavior, (2) generating some initial ideas or hunches about that phenomenon, or (3) testing the feasibility of undertaking a more extensive study regarding that phenomenon. For instance, when I began researching community responses to placements of people with a history of sexual offending in communities, very few previous studies had examined my problem of interest. At first, I conducted exploratory research to understand community members’ major concerns about the placements, and how they presented those concerns in public meetings. I read news reports about previous community meetings, visited some meetings, and talked with community members. These research activities helped me understand the problem and generate initial ideas about how different communities responded to proposed placements. I also gained some insights into how I might structure a larger study on the topic.

Description

Conducting descriptive research means that a researcher wants to describe or define a particular phenomenon through systematic observation of a phenomenon of interest. These observations must be based on the scientific method so they are more reliable than casual observations by untrained people. Examples of descriptive research include tabulations of demographic statistics by the United States Census Bureau, or crime rates by the FBI. Both sources use the same or similar systematic data collection methods over time.

Descriptive research often focuses on “what, where, and when” questions. For example, when our local police department wanted to know what residents thought of them, we conducted a door-to-door survey in which we asked about all sorts of topics related to police and policing. The goal was to provide city administration with an overview of how people in our city viewed police work and interactions. I presented the results to the city council by showing charts with the percentages of people who had answered each question category. Other descriptive research may include chronicling gang activities among adolescent youth in urban populations, police-community interactions, and the role of technologies (such as Twitter and instant messaging) in the spread of ideas about the criminal justice system. Each example relies on systematically collecting data to describe social phenomena by answering “what, where, and when” questions.

Explanation

While descriptive research examines the “what, where, and when” of a phenomenon, explanatory research seeks to answer “why” and “how” types of questions. Explanatory research tries to identify the causes and effects of the phenomenon being studied. In other words, this type of research attempts to “connect the dots” in research by identifying causal factors and outcomes of the target phenomenon. For example, when the results of the policing study indicated differences in opinions throughout the city, we moved into more explanatory research to determine why and how people’s perceptions of the police were different. We found that the type of neighborhood and the respondents’ racial and ethnic groups impacted their perceptions of the police. These findings helped explain some of the variation in opinions of police across people in our study. Other examples of explanatory research include understanding the reasons behind sexual violence to suggest strategies for solving the problem, figuring out why black people are disproportionately incarcerated, and trying to explain the factors that impact prosecutors’ charging decisions.

Summary

- Nine major components of research design include ethics, previous studies, research questions, research strategies and goals, conceptualization and operationalization, sample, and data collection methods.

- Literature reviews require strategic searching for and reviewing previous studies. Searching strategies include broadening or narrowing your

search terms, finding articles about a similar population or broader topic than your research question, and using articles you’ve found to identify other articles. Reviewing articles may involve writing an annotated bibliography or literature review, so you should learn to mine scholarly articles for the most important information rather than read them from start to finish. - Inductive research approaches take a theory-building approach, starting with observations and then analyzing up to build broader theories. Deductive approaches take a theory-testing approach of starting with theoretical propositions and then analyzing them down to test propositions using empirical data.

- Exploratory, descriptive, and explanatory research have different goals. Exploratory research aims to learn more about a relatively new area of inquiry. Descriptive research aims to describe a particular phenomenon. Explanatory research aims to answer causal questions about why and how social phenomena occur.

Key Terms

| Abstract | Exploratory Research | Theory-Building |

| Annotated Bibliography | Hypotheses | Theory-Testing |

| Deductive | Inductive | |

| Descriptive Research | Interpretive Methods | |

| Explanatory Research | Data Collection Methods |

Discussion Questions

- How would you review the literature to write an annotated bibliography related to a topic you might be interested in researching? Identify the steps you would take and how you might organize your results.

- What are some of the strengths and weaknesses of inductive and deductive designs?

- Develop three research questions: one each for an exploratory, descriptive, and explanatory research project. Explain how each research question fits with the relevant research goal.

Media Attributions

- Figure 5.1 Components of a Research Project © Williams, Monica is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 5.2 Inductive approach to research © Williams, Monica is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 5.3 Deductive approach to research © Williams, Monica is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license