1 Scientific Research

What is research? You will likely get different answers to this seemingly innocuous question depending on who you ask. Some people say they conduct research by reading news reports or product reviews. Television news channels conduct research by polling viewers on topics like upcoming elections or proposed government-funded projects. Undergraduate students research online to find

the information they need to complete assigned projects or papers. Graduate students might view research as collecting or analyzing data related to a specific project. Local police departments might say that they research solutions to problems– such as lack of trust in law enforcement– by holding community meetings to listen to community members’ concerns. Despite all the ways the term “research” can be used in everyday life, scientific research projects rely on systematically collecting and analyzing data using scientifically valid strategies. This chapter will help you understand the definition of science, how scientific knowledge differs from other types of knowledge, and three key elements of the scientific research process.

Science

Etymologically, the word “science” is derived from the Latin word scientia meaning knowledge. Science refers to a systematic and organized body of knowledge in an area of inquiry. Science can be grouped into two broad categories: natural and social.

Natural science is the science of naturally occurring objects or phenomena, such as light, objects, matter, earth, celestial bodies, or the human body. Natural sciences can be further classified into physical sciences, earth sciences, life sciences, and others. Physical sciences consist of disciplines such as physics (the science of physical objects), chemistry (the science of matter), and astronomy (the science of celestial objects). Earth sciences consist of disciplines such as geology (the science of the earth). Life sciences include biology (the science of human bodies) and botany (the science of plants).

Social science is the science of people or collections of people, such as groups, organizations, societies, economies, and individual or collective behaviors. Social sciences can be classified into disciplines such as psychology (the science of human behaviors), sociology (the science of social groups), and economics (the science of firms, markets, and economies). While these are distinct disciplines, they often overlap and create interdisciplinary fields such as criminal justice studies.

Scientific Knowledge

Consider for a moment how you know what you know. When you sit in the driver’s seat of a car, how do you know what will happen when you press your foot on one of the pedals? How do you know the rules of a sport? If you play a sport, how might you have learned the sport in different ways than someone who loves to watch but has never played? How do you know about issues happening in places other than your community? Think about your major or program of study. How do you know what you know about the criminal justice system, psychological phenomena, or the role of social norms in society? As these questions illustrate, our knowledge about the world comes from many different sources including textbook-based information, trial and error, news media, and scientific studies.

Some sources of our knowledge about the world include experiences, authority, and scientific research. Three types of experiential knowledge include informal observations, selective observations, and overgeneralization. Informal observation is a way of knowing based on watching the world around us and drawing conclusions without any systematic process for observing or analyzing our observations. Direct experiences with the social world can provide this type of knowledge. For example, if you pass a police officer driving 20 miles over the speed limit on a two-lane highway, you’ll probably learn that’s a good way to earn a traffic ticket. The problem with informal observation is that sometimes it is right, and sometimes it is wrong. Without any deliberate, formal process for observing or assessing the accuracy of our observations, we can never really be sure of the accuracy of our informal observations. In the example of the speeding ticket, you may receive a ticket in one instance, but not another. Through informal observations, you might start to believe that factors such as having a blue car or out-of-state license plates impact your chances of receiving a ticket, but you have no way of determining whether that is true.

Selective observation occurs when we base our beliefs only on the patterns we want to see or think we see in our everyday lives. This is also called confirmation bias because we see events that confirm existing conclusions and disregard other events that could challenge those conclusions. Sometimes, these observations are based on stereotypes. For example, if a police officer pulls over a car driven by a black man, receives consent to search the car, and finds drugs in the car, she may conclude that black drivers probably have drugs in their cars. Imagine the officer then pulls over two more cars, one driven by a black man and one by a white woman. If she finds drugs in both cars, she may disregard the drugs in the white driver’s car as an anomaly, while using the drugs in the black driver’s car as an example that reinforces the perceived pattern of drugs in black drivers’ cars. Over time, the perceived pattern may become so entrenched that she asks to search the cars of black drivers more than white drivers, further reinforcing the perception of a pattern of drugs being found more often in black drivers’ cars.

If we asked the officer to think more broadly about her experiences with finding drugs in cars she’s pulled over, she would probably acknowledge that she had encountered many white drivers with drugs in their cars while black drivers she’d pulled over hadn’t had drugs in their cars. This officer engaged in selective observation by noticing only the pattern that she wanted to find at the time. On the other hand, if the officer’s experience with the first black driver had been her only experience with any black driver, she would have been engaging in overgeneralization by assuming that broad patterns exist based on limited observations.

While experiences shape much of our knowledge about the world, people in positions of authority also contribute to what we know. We might rely on parents, government agencies, school administrators, teachers, and church leaders as sources of knowledge about the world. Often, the information we hear from these authority figures can become embedded in our knowledge in the form of ideas we’ve always known to be true. It makes sense that we might believe something to be true because someone we look up to or respect has said it is so, and this type of knowledge often forms the basis for scientific research questions. However, knowledge rooted in authoritative statements differs from scientific knowledge derived from systematic inquiry into a particular topic.

Scientific knowledge refers to a generalized body of laws and theories that explain a phenomenon or behavior and are acquired using the scientific method. The goal of scientific research is to observe patterns of phenomena or behaviors (i.e., laws) and propose systematic explanations of the underlying phenomenon or behaviors (i.e., theories). Social scientific knowledge is knowledge based on systematically observing and explaining social phenomena.

Scientific knowledge may be imperfect or even quite far from the truth. Sometimes, there may not be a universal truth but rather an equilibrium of “multiple truths.” The theories that emerge from scientific knowledge, and contribute to the further study of a phenomenon or behavior, are created by scientists to explain a particular phenomenon. As such, theories may be strong or weak explanations, depending on how they fit with reality. All scientific knowledge changes over time with further study using more accurate methods and more informed logical reasoning.

The Scientific Research Process

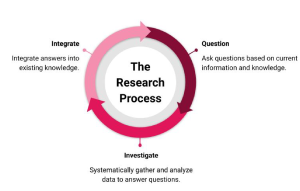

The preceding section described science as knowledge acquired through a scientific method. So, what exactly does the scientific research process look like? First, research is a never-ending cycle. We ask questions, investigate answers, and integrate our findings into existing knowledge. Then, our new findings introduce more questions and the cycle begins again. The goal of scientific research is not to find the answer; rather, the scientific research process seeks to provide new insights into ongoing questions and conversations about a particular topic. Those insights always lead to new questions and new investigations. Figure 1.1 illustrates the key features of the scientific research process: questioning, investigating, and integrating.

The circular model of the research process provides a broad overview of the scientific research process. This textbook focuses somewhat on the questioning phase of the process and mostly on the investigation phase. However, a solid understanding of the entire research cycle helps illustrate the importance of each phase. The questioning phase is a type of exploration of the social world. Researchers may start with a question about the social world that emerges from informal or selective observations, authoritative knowledge, or other scientific studies. Forming research questions often requires examining the published literature on a topic to understand the current state of knowledge in that area and identifying theories that may help answer the research questions.

Once a researcher has identified a question, they systematically gather and analyze data to investigate potential answers. Scientific investigation starts with designing a research project that serves as a blueprint of the activities needed to answer the research questions. Research design includes selecting a research method, designing precise measures for abstract theoretical constructs, and devising an appropriate strategy for finding a subset of the population to study. Later chapters in this book cover each of these elements of the investigation stage of research. For now, let us consider some questions researchers must answer as they design their research project.

In selecting a research method, researchers must decide whether their research question would best be answered using numerical or narrative data. Would a survey, experiment, case study, or interview be the most likely to provide answers to the research questions? The type of research question will determine the research method, but even when a researcher has chosen the method, more questions need to be answered. For example, what will differentiate between the experimental and control groups, if the researcher plans an experiment? If a survey is chosen, will it be administered by mail, telephone, internet, or a combination of some or all of these? Would multiple methods make the most sense?

With any given research method the researcher must know how to measure abstract constructs. This is especially relevant to social science research because many of the constructs researchers are interested in are hard to define, let alone measure accurately. For example, how would you define prejudice, alienation, or liberalism? Once you have come up with an adequate definition, how would you measure a person’s level of prejudice? What about their alienation from society or their liberalism? Sometimes, researchers can use measures developed by previous researchers to study the same constructs.

Other times, such measures are unavailable, and the researcher must design new ways to measure their constructs. This can easily be a long and laborious process, with multiple rounds of pretests and modifications before the newly designed instrument can be accepted as scientifically valid.

Next, researchers must carefully choose the target population from which they wish to collect data and develop an appropriate strategy for finding a subset of the population to study. Sampling involves answering many questions about the researcher’s intended population. For example, does the research question require looking at individuals, communities, neighborhoods, states, or countries? What types of these entities should the researchers target? The scientific research process requires answering these questions using scientifically valid techniques, which are discussed later in this book.

Having designed the blueprint for the research project, the researcher then implements the research plan. Some researchers may conduct small-scale tests (also called pilot tests) of their plans for measuring constructs to work out any potential problems in the research design or measurements. After successful pilot testing, the researcher may proceed with collecting, analyzing, and interpreting data based on the research plan.

Researchers must keep an open mind during the investigation phase because the findings may or may not align with presumed answers or findings from previous scientific studies. Regardless of how well the findings fit with previous knowledge or preconceived ideas of what answers would be found, the new findings contribute to ongoing conversations in the scientific world about the phenomenon under study. In the final phase of the scientific research process, the researcher integrates their findings into existing scientific knowledge by summarizing the research project and its findings in the context of previous scientific work on the topic. The final research report documents the entire research process and findings. It provides detailed descriptions, justifications, and outcomes of all the choices made during the research process (e.g., theories, constructs, measures, research methods, sampling, etc.).

The research report allows other researchers to determine the extent to which the research project adhered to the scientific method, a standardized set of techniques for building scientific knowledge. These techniques include strategies for making valid observations, accurately interpreting results, and generalizing those results beyond a specific research study. In the social sciences, the scientific method includes various research approaches, tools, and techniques for collecting and analyzing different types of data. This book introduces you to these approaches in later chapters. For now, let us look more broadly at four key elements that characterize scientific inferences and findings:

- Logic: Scientific inferences must be based on logical principles of reasoning.

- Confirmability: Inferences must match observed evidence.

- Replicability: Other scientists must be able to independently replicate or repeat a scientific study and obtain similar, if not identical, results.

- Scrutiny: The procedures and inferences must withstand critical review by other scientists (peer review).

The final research report must include enough detail to demonstrate the logic, confirmability, and replicability of the research project, so other researchers can critically review the study and its findings to determine whether the project meets the standards necessary to contribute to scientific knowledge.

As you begin to think like a researcher, you will see the world as a set of potential research questions that need scientific study. Remember, even a research project that adheres to the scientific method’s four characteristics can only partially answer a given research question. Research is a career-long process of questions, investigations, and integration.

Summary

- Science is a systematic, organized body of knowledge in a particular area of inquiry and can be grouped into natural science and social science.

- Scientific knowledge is distinct from other types of knowledge (e.g., informal observation, selective observation, overgeneralization, and authority) in its focus on systematic observation and explanation of social phenomena using the scientific research process.

- The scientific research process can be broadly categorized into three phases—questioning, investigating, and integrating—that repeat in a cycle as more scientific knowledge is produced.

- The scientific method provides a set of techniques for building scientific knowledge that reflects key scientific tenets of logic, confirmability, replicability, and withstand scrutiny.

Key Terms

| Authority | Overgeneralization | Scientific Method |

| Confirmability | Peer Review | Scientific Research |

| Informal Observation | Questioning Phase | Pilot Tests |

| Integration Phase | Replicability | Selective Observation |

| Investigation | Sampling | Social Science |

| Phase Logic | Science | |

| Natural Science | Scientific Knowledge |

Discussion Questions

- How are the natural sciences similar to and different from the social sciences?

- How do you know what you know? List an example from your own life that illustrates each of the five types of knowledge covered in this chapter.

- Think about a time that you researched an issue. What steps in the scientific research process did you take? What steps did you skip? Would your research be considered scientific research? Why or why not?

- What question(s) do you have about the social world that could be answered using scientific research? How might scientists go about investigating answers to that question? What population might they choose? How might they integrate their findings into existing scientific knowledge?

- Why are each of the four key elements of scientific inferences and findings important to scientific knowledge and the scientific research process?

Media Attributions

- Figure 1.1 The Scientific Research Process © Williams, Monica is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license