College of Social and Behavioral Science

143 Does Maternal Sensitivity Mediate the Intergenerational Impact of Maternal Emotion Dysregulation?

Thea Wulff

Faculty Mentor: Lee Raby (Psychology, University of Utah)

A Senior Honors Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of

The University of Utah

Abstract

Emotion dysregulation involves difficulties with recognizing and accepting one’s emotions and modulating emotional responses and behaviors to act in alignment with one’s goals. Mothers’ emotion dysregulation may have intergenerational implications for the developing child. Of particular interest in this study are children’s risks of developing socioemotional difficulties underlying psychopathology. Mothers’ parental sensitivity during parent-infant interactions may be involved in mediating the impact of a mother’s emotion dysregulation on the young child’s socioemotional outcomes. Parental sensitivity is generally conceptualized as an ability to “follow the child’s lead” through an awareness of their needs, moods, interests, and capabilities. The aims of the current study are: (1) to test whether mothers’ emotion dysregulation during pregnancy predicts toddlers’ socioemotional difficulties and (2) examine whether maternal sensitivity during infancy mediates the intergenerational association between maternal emotion dysregulation and toddlers’ socioemotional difficulties. Data were collected from 385 mothers (average age = 29 years) who were recruited while pregnant. Mothers’ self-reported difficulties with emotion regulation were assessed at a prenatal visit. The mothers were observed interacting with their infants during a non-distressing 10-minute play task when their infants were approximately 7 months old, and their sensitivity to the infants’ signals was rated by a team of trained coders. When the children were age 18 months, mothers reported on their toddlers’ socioemotional difficulties using a well validated parent-report measure. Consistent with my first hypothesis, the results indicated that mothers who reported higher prenatal emotion dysregulation had toddlers with greater externalizing behavior problems, internalizing behavior problems, and dysregulation. Contrary to my second hypothesis, maternal sensitivity did not significantly mediate these intergenerational associations. Specifically, mothers with higher prenatal emotion dysregulation were not significantly less sensitive during non-distressing mother-infant interactions, and maternal sensitivity during infancy did not significantly predict toddlers’ socioemotional outcomes. The results of this study support the idea that programs designed to support mothers’ mental health may also have benefits for their children.

Introduction

Emotion regulation is conceptualized as an awareness, understanding, and acceptance of one’s emotions, as well as the ability to modulate emotional responses and control behaviors in order to act in alignment with goals when experiencing negative emotions (Gratz & Roemer, 2004). In contrast, emotion dysregulation is marked by difficulties with these components. Emotion regulation is widely acknowledged as a critical facet of one’s well-being throughout childhood, adolescence, and adulthood (Brewer et al., 2016; Daniel et al., 2020; Gross & Munoz, 1995). Conversely, emotion dysregulation is thought to underlie many abnormal behaviors and psychopathology symptoms, including borderline personality disorder, self-injurious thoughts and behaviors, depression, and anxiety (Lin et al., 2019). In this way, emotion dysregulation functions as a risk factor for multiple clinical diagnoses (Beauchaine & Cicchetti, 2019).

Emotion dysregulation among parents also is thought to have intergenerational implications for the developing child, especially children’s socioemotional development (Keenan, 2000; Li et al., 2019). For example, mothers’ self-reported emotion regulation difficulties predict behavioral problems in children, including internalizing behaviors like anxiety and depression and externalizing behaviors like aggression and defiance (Leerkes et al., 2020). However, many of these studies focus on children at preschool age or older, so there is a general lack of information about implications of emotion dysregulation for children’s outcomes during early toddlerhood. Gaining an understanding of what transpires during this early time period is essential in targeting early intervention to ameliorate the effects of intergenerational emotion dysregulation.

A second critical gap in this field of research is identifying the precise mechanisms by which maternal emotion dysregulation may influence children’s early socioemotional outcomes. Parenting behaviors might be one mechanism through which this occurs, as maternal emotion dysregulation has important implications for parenting behaviors during infancy and later child development (Dix, 1991; Leerkes et al., 2020; Teti & Cole, 2011). One key dimension of parenting behavior that is especially important during infancy is parental sensitivity. Parenting sensitivity is generally conceptualized as the mother’s ability to “follow the child’s lead” through an awareness of the child’s needs, moods, interests, and capabilities (Ainsworth et al., 2015). A highly sensitive mother is able to accurately perceive and interpret their child’s cues and respond appropriately, whereas an insensitive mother is often intrusive, disengaged, or hostile towards their child (Rosenblum et al., 2020).

Maternal sensitivity during parent-child interactions might mediate the impact of a mother’s emotion dysregulation on the child’s outcomes. Parents’ effective regulation of negative emotions can lend itself to sensitive parenting behaviors (Dix, 1991; Teti & Cole, 2011). Conversely, higher emotion dysregulation is associated with decreased sensitivity to the child’s needs during parent-child interactions (Borairi et al., 2024; Carreras et al., 2019; de Campora et al., 2014; Leerkes et al., 2020). These findings are consistent with evidence that mental health disorders like depression can disrupt sensitive parenting behaviors, possibly through a reduced emotion regulation capacity (Bernard et al., 2018; Borairi et al., 2024; Haga et al., 2012). It is also generally recognized that maternal sensitivity promotes more competent outcomes among young children (Frick et al., 2018). For example, a recent meta-analysis of over 100 studies indicated that parenting sensitivity has small but statistically significant negative associations with internalizing behavior problems and externalizing behavior problems among children (Cooke et al., 2022). However, very few studies have directly tested whether maternal sensitivity mediates the intergenerational associations between parental emotion dysregulation and child outcomes using a longitudinal research design.

The purpose of this study was to address these research gaps. The first aim of this project was to examine whether maternal emotion dysregulation during pregnancy predicts toddler socioemotional outcomes. The second aim was to test whether maternal sensitivity to their infants’ signals during mother-infant interactions mediates the intergenerational associations between prenatal maternal emotion dysregulation and toddlers’ socioemotional outcomes. Data for the project were collected from 385 mother-child dyads between pregnancy and 18 months postpartum. Maternal self-reported emotion dysregulation was measured during the third trimester of pregnancy, observations of maternal sensitivity were collected when children were approximately 7-months old, and toddlers’ socioemotional outcomes were measured using parent-report questionnaires when the children were 18-months old.

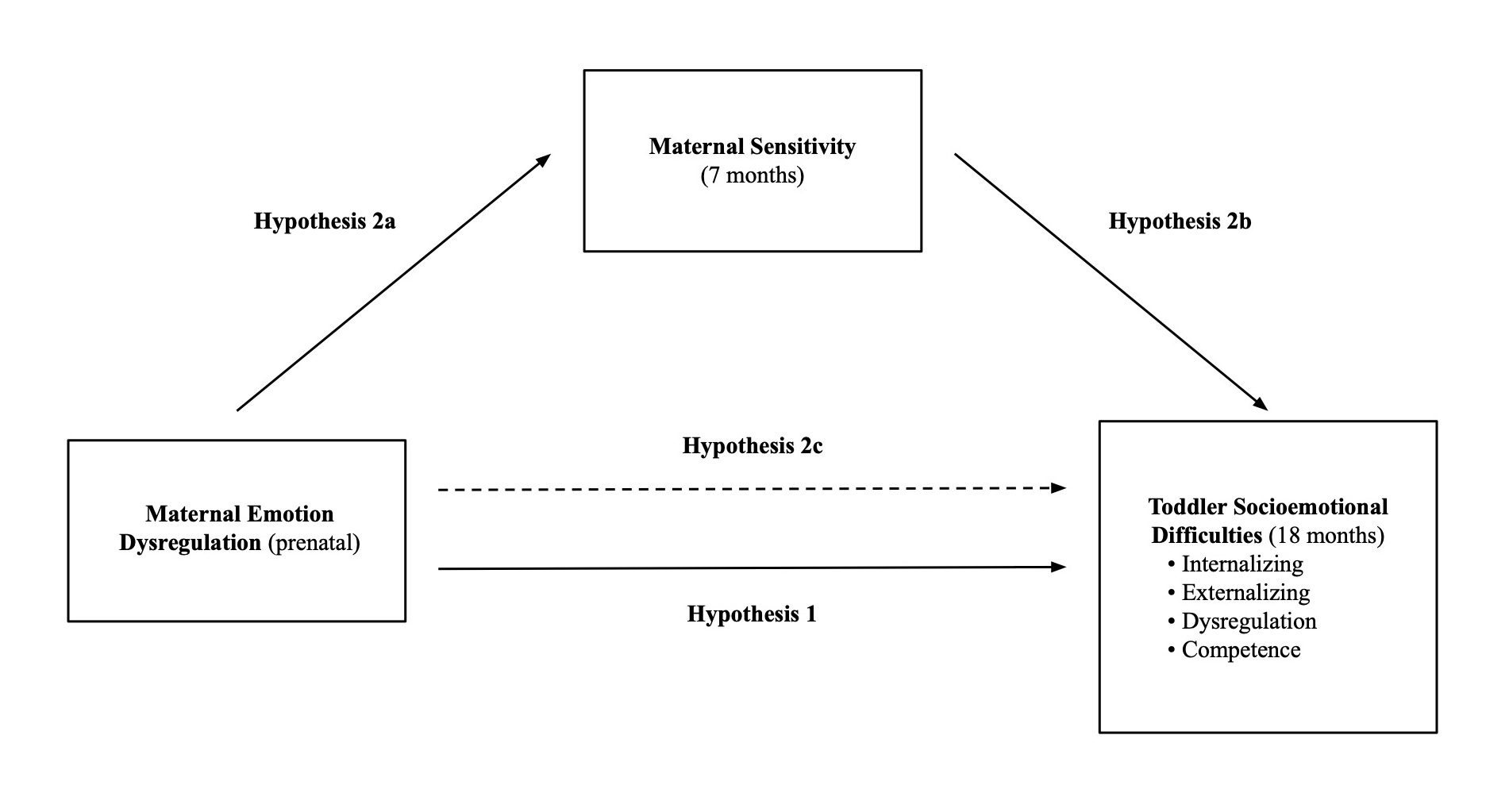

I hypothesized that mothers who report higher prenatal emotion dysregulation would have toddlers with greater socioemotional difficulties (Hypothesis 1). I hypothesized that mothers with higher prenatal emotion dysregulation would be less sensitive during non-distressing mother-infant interactions (Hypothesis 2a) and that mothers who are less sensitive to infants would have toddlers with greater socioemotional difficulties (Hypothesis 2b). Lastly, I hypothesized that the association between prenatal emotion dysregulation and toddlers’ socioemotional outcomes would be significantly weaker after accounting for maternal sensitivity (Hypothesis 2c). See Figure 1 for an illustration of the hypothesized model.

Figure 1. Hypotheses regarding the intergenerational associations between maternal prenatal emotion dysregulation and toddlers’ socioemotional difficulties (Hypothesis 1) as well as the mediational role of maternal sensitivity (Hypotheses 2a, 2b, and 2c).

METHODS

Participants

The data used in this project were collected from the Baby Affect and Behavior Study (BABY), which is a longitudinal project that examines the intergenerational transmission of emotion dysregulation from mother to child. Pregnant individuals were recruited from Salt Lake City and the surrounding area through their obstetrician appointments and through flyers, brochures, and posts on social media. Eligibility criteria included being between 18 and 40 years old, at least 25 weeks pregnant, no pregnancy complications, no substance use during pregnancy, and a plan to deliver at a participating hospital. Those interested in participating completed a brief demographic questionnaire to determine eligibility as well as the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004). In order to facilitate a sample with a uniform distribution of emotion dysregulation scores, pregnant individuals with high and low DERS scores were intentionally oversampled. In addition, pregnant individuals who identified as belonging to a minority racial/ethnic group were also intentionally oversampled to increase the racial/ethnic diversity of the sample.

A total of 385 pregnant individuals were ultimately included in the BABY project. Most (60%) mothers identified as White/non-Hispanic, 20% identified as Hispanic, and 20% identified as a different non-White race or ethnicity. Mothers’ ages ranged from 18 to 40 years (average of 29 years old). Mothers reported a median household income of $50,000 to $79,999, and 55% of the mothers had graduated college. Approximately 52% of the children were assigned female at birth, and 48% were assigned male.

Procedure

This thesis focuses on data collected from these 385 mother-child dyads during the prenatal, 7-month, and 18-month time points. Mothers completed the DERS during their third trimester of pregnancy. Later, they were observed playing with their infants during a non-distressing interaction when their infants were approximately 7-months old. When the children were 18 months, mothers reported on their toddlers’ socioemotional outcomes.

Measures

Maternal emotion dysregulation (prenatal). Mothers completed the DERS (Gratz & Roemer, 2004) during their third trimester of pregnancy. The DERS is a well-validated self-report questionnaire that includes 36 questions designed to assess adults’ emotion regulation difficulties in six domains, including nonacceptance of emotional responses, difficulty engaging in goal-directed behavior, impulse control difficulties, lack of emotional awareness, limited access to emotion regulation strategies, and lack of emotional clarity. Examples of questions asked on the DERS include: “I experience my emotions as overwhelming and out of control” and “I have difficulty making sense out of my feelings.” Participants respond to these questions on a 5-point Likert scale (1 – almost never to 5 – almost always). A total emotion dysregulation score was created by reverse scoring relevant questions and then calculating the average of the 36 items. A higher score indicates greater difficulty with regulating emotions.

Maternal sensitivity (7 months). Maternal sensitivity to the child was observed during a non-distressing 10-minute play interaction at the 7-month visit. The observations were coded using the Observational Record of the Caregiving Environment, which is a well-validated system for coding parental sensitivity to their infant’s signals (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1996). Parental behavior was coded using four scales. The first was sensitivity to non-distress, which captures the mother’s ability to “follow the child’s lead” through an awareness of the child’s needs, moods, interests, and capabilities (Bernard et al., 2013). The second rating was intrusiveness, which represents the extent to which the mother pushes their agenda on the child (i.e., adult-centered play), despite indicators that a different activity, level, or pace of interaction is needed. The third rating was detachment, which indicates whether a mother is emotionally uninvolved in the interaction or unaware of the child’s needs for appropriate interaction to facilitate involvement with objects or people. The fourth rating was positive regard, which reflects the mother’s positive feelings toward the child, including behaviors like speaking in a warm tone of voice, affectionate physical contact, and listening and watching attentively. For each of these scales, the mother’s behavior was rated using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from one to five. Half scores were permitted. Each video was independently coded by two trained coders, and the correlations between the scores assigned by the two coders were between .54 and .70 for the four scales. Coders’ scores were conferenced to arrive at a final score for each scale.

There is meta-analytic evidence that composite measures of maternal sensitivity predict child behavior problems more strongly than single scales (Cooke et al., 2022). For this reason, a composite measure of maternal sensitivity was created. Specifically, maternal intrusiveness and detachment were reserve-scored, and a composite measure of overall maternal sensitivity during the free-play interaction was created by averaging the scores for the four ratings.

Toddler socioemotional outcomes (18 months). Mothers completed the Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (ITSEA; Carter et al., 2003) at the 18-month visit. The ITSEA is a comprehensive parent-report questionnaire that includes 166 items that examine children’s externalizing and internalizing behavioral problems, regulation abilities, and socioemotional competencies. The behaviors include those that are atypical for normal child development, as well as behaviors that are done in excess or are lacking when compared to typical development. The ITSEA includes 17 subscales that can be consolidated into four domains. The first domain is externalizing behaviors, which captures children’s activity/impulsivity, aggression/defiance, and peer aggression. The second domain is internalizing behaviors, which is composed of toddlers’ depression/withdrawal, general anxiety, separation distress, and inhibition to novelty. The third domain is dysregulation, which assesses toddlers’ sleep problems, negative emotionality, eating difficulties, and sensory sensitivities. The fourth domain is competence, which includes toddlers’ compliance, attention, imitation/play, mastery, motivation, empathy, and prosocial peer relations. I examined each of these domains separately in my analyses. Questions are answered using a 3-point Like scale (0 = not true or rarely, 1 = somewhat true or sometimes, 2 = very true or often). Composite scores were created by reverse scoring the necessary items and then calculating the average of the relevant questions.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

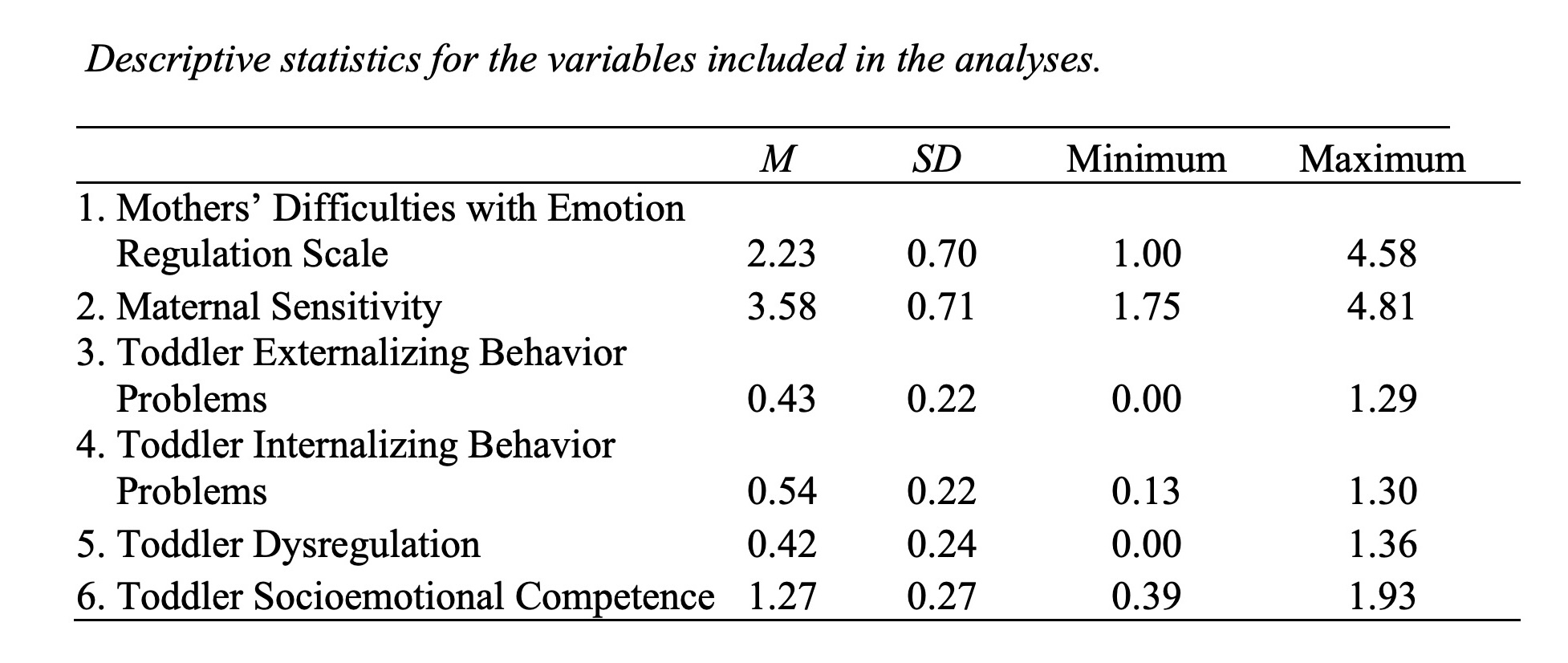

The descriptive statistics for the variables included in the analyses are reported in Table 1. All descriptive statistics were run in RStudio. The average DERS was 2.23, which suggests that mothers’ responses tended to fall in the midpoint on this 5-point scale. The minimum score on the DERS was 1.00 (equivalent to selecting “almost never” for all items) and the maximum score was 4.58 (which is between “most of the time” and “almost always”), indicating that mothers’ levels of self-reported emotion dysregulation exhibited wide variability.

The average for mothers’ parental sensitivity was 3.58, suggesting that mothers tended to receive scores between a 3 (somewhat characteristic) and a 4 (moderately characteristic) in their sensitive parenting behaviors on the 5-point rating scales. Parental sensitivity had a minimum of 1.75 and a maximum of 4.81, indicating that some mothers received low ratings, while other mothers received very high ratings.

The average scores for ITSEA externalizing behaviors, internalizing behaviors, and dysregulation were between 0.42 and 0.54, suggesting that, on average, mothers reported their toddlers’ problematic behaviors as falling between 0 (not true/rarely) and 1 (somewhat true/sometimes). Scores on these scales ranged from a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 1.36, indicating a relatively wide range in toddlers’ problematic behaviors in this sample.

The average score for ITSEA competence was 1.27, suggesting that, on average, mothers reported behaviors related to their toddlers’ competence as falling between 1 (somewhat true/sometimes) and 2 (very true/often). Scores ranged from a minimum of 0.39 to a maximum of 1.93, indicating substantial variability in mothers’ reported behaviors related to their toddlers’ competence.

Table 1.

Correlational Analyses

For this study, I addressed two main research questions. First, I examined whether maternal emotion dysregulation during pregnancy predicted toddler socioemotional difficulties. I hypothesized that mothers who report higher prenatal emotion dysregulation would have toddlers with greater externalizing behavior problems, internalizing behavior problems, and dysregulation as well as lower socioemotional competence (Hypothesis 1). I used Pearson’s product-moment correlation in RStudio to evaluate whether the correlations among these variables were statistically different from zero. As I expected, maternal emotion dysregulation was positively correlated with toddlers’ externalizing behavior problems (r = .18, p = .008), internalizing behavior problems (r = .16, p = .007), and dysregulation (r = .18, p = .002). In contrast to my hypothesis, maternal emotion dysregulation was not significantly correlated with toddlers’ socioemotional competence (r = .00, p = .96).

Second, I examined whether maternal parenting sensitivity at least partially mediates the association between maternal emotion dysregulation and toddler socioemotional outcomes. I hypothesized that mothers with higher prenatal emotion dysregulation would be less sensitive during non-distressing mother-infant interactions (Hypothesis 2a). I used Pearson’s product-moment correlation in RStudio to determine whether the correlation between these variables was statistically different from zero. In contrast to my hypothesis, maternal emotion dysregulation was not significantly correlated with parenting sensitivity (r = -.09, p = .15).

I also hypothesized that mothers who were less sensitive to infants would have toddlers with greater externalizing behavior problems, internalizing behavior problems, and dysregulation as well as less socioemotional competence (Hypothesis 2b). I used Pearson’s product-moment correlation in RStudio to determine whether the correlations among these variables are statistically different from zero. In contrast to my hypothesis, maternal sensitivity was not significantly correlated with toddlers’ externalizing behavior problems (r = -.09, p = .21), internalizing behavior problems (r = .07, p = .27), dysregulation (r = -.04, p = .51), or socioemotional competence (r = .01, p = .92).

Mediation Analyses

Lastly, I hypothesized that the association between prenatal emotion dysregulation and toddlers’ socioemotional outcomes would be significantly weaker after accounting for maternal sensitivity (Hypothesis 2c). To test that hypothesis, I ran a mediation analysis for each of the four socioemotional outcomes (externalizing behavior problems, internalizing behavior problems, dysregulation, and competence). These mediation analyses were run in RStudio using the lavaan package. Contrary to my hypothesis but consistent with the results of the correlational analyses reported above, I found that the indirect effect between prenatal emotion dysregulation via the mediator (maternal sensitivity) was not significant for toddler externalizing behavior problems (p = .28), toddler internalizing behavior problems (p = .29), toddler dysregulation (p = .67), or toddler socioemotional competence (p = .81). Even after accounting for maternal sensitivity, DERS predicted toddler’ externalizing behavior problems (β = .20, p = .004), internalizing behavior problems (β = .16, p = .007), and dysregulation (β = .18, p = .003). DERS did not significantly predict toddler socioemotional competence with maternal sensitivity included in the model (β = -.02, p = .75).

Discussion

The first aim of this project was to examine whether maternal emotion dysregulation during pregnancy predicted toddler socioemotional difficulties. As I hypothesized, mothers’ prenatal emotion dysregulation was positively correlated with toddlers’ externalizing behavior problems, internalizing behavior problems, and dysregulation. These results align with the findings of other studies which suggest that maternal emotion dysregulation predicts later behavioral problems in children, particularly internalizing behaviors, externalizing behaviors, and socioemotional dysregulation (Leerkes et al., 2020). My project also extends findings in existing literature, as maternal emotion dysregulation was assessed at the prenatal time point, compared to many studies that examine emotion dysregulation postnatally. Measuring maternal emotion dysregulation prenatally is important because it helps reduce the likelihood that the associations between maternal emotion dysregulation and toddler outcomes are due to children evoking emotion dysregulation. Because maternal emotion dysregulation was measured before the child was born, there is increased confidence that it is the mother’s emotion dysregulation shaping toddler outcomes, rather than the other way around. Also, children’s outcomes were assessed during toddlerhood for the current study, rather than at preschool age or older as is common in other research in this area (e.g., Leerkes et al., 2020). Given that children’s brains are generally assumed to be especially plastic during the first couple years of development, it is critical that research examines these early years. Understanding when these problems develop can contribute to more effective early intervention strategies.

In contrast to my hypothesis, maternal emotion dysregulation was not significantly correlated with toddlers’ socioemotional competence. It is possible that the early emergence of competence is not shaped by the home environment (including maternal emotion regulation), but instead by other factors that may be more in line with temperament. It is also possible that competence might appear more strongly associated with features of the home environment at a later age. Existing literature suggests that toddlers who exhibit early behavior problems like externalizing behavior problems and dysregulation are at greater risk for developing problems with socioemotional competence at around 5 years old (Blandon et al., 2010).

The second aim of this project was to examine whether maternal parenting sensitivity at least partially mediates the association between maternal emotion dysregulation and toddler socioemotional outcomes. In contrast to my hypothesis, parenting sensitivity was not significantly correlated with maternal emotion dysregulation or with toddlers’ externalizing behavior problems, internalizing behavior problems, dysregulation, or socioemotional competence. Thus, the indirect effects of maternal emotion dysregulation and toddler socioemotional outcomes via parenting sensitivity were not significant.

Prior studies have suggested that parents’ effective regulation of negative emotions can lend itself to sensitive parenting behaviors (Dix, 1991; Teti & Cole, 2011) and conversely that emotion dysregulation is associated with decreased sensitivity to the child’s needs during parent-child interactions (Borairi et al., 2024; Carreras et al., 2019; de Campora et al., 2014; Leerkes et al., 2020). In contrast, the results of this study indicated that maternal emotion dysregulation was not significantly correlated with parenting sensitivity. It is possible that measuring maternal emotion dysregulation prenatally does not accurately capture the mother’s emotion dysregulation after the birth of the child. The measure of maternal sensitivity used in this project may also be an incomplete picture of the quality of caregiving mothers generally provide for their children on a day-to-day basis. For example, using multiple observations of parenting sensitivity may provide a more complete measure of the quality of caregiving mothers generally provide for their children. Existing research indicates that effect sizes between maternal sensitivity and related variables increased as the number of observations of maternal sensitivity increased (Lindhiem et al., 2010).

In general, maternal sensitivity has been found to be associated with more competent outcomes among young children (Frick et al., 2018). For example, a recent meta-analysis of over 100 studies indicated that parenting sensitivity is negatively associated with internalizing behavior problems and externalizing behavior problems among children (Cooke et al., 2022). In contrast to this existing literature, my project found that maternal sensitivity was not significantly correlated with toddlers’ externalizing behavior problems, internalizing behavior problems, dysregulation, or socioemotional competence. While these associations observed in this study were not statistically different from zero, it is important to note that the magnitude of the association for toddler externalizing behavior problems was similar to those reported in the meta-analysis (r = -.09 and r = -.14, respectively; Cooke et al., 2022). It is possible that the current project lacked sufficient power to generate a significant effect. This is despite the fact that the current study had a sample size of 385, which is nearly three times as large as the median sample size of prior studies included in the meta-analysis (Cooke et al., 2022). In other words, although the current had a relatively large sample size, an even larger sample size might be necessary to detect the small effects of maternal sensitivity on child behavior problems as statistically significant.

Future Directions

A potentially valuable direction for future research would be to examine different measures of maternal sensitivity. Specifically, this project used a measure of maternal sensitivity during free-play interactions when infants were not distressed. It is possible that parental responses to an infant’s distress cues may be more strongly associated with children’s later socioemotional outcomes than responses to play/exploration, which may be a better predictor of cognitive outcomes. For example, maternal sensitivity to infant distress has been shown to be associated with fewer behavior problems at 24 and 36 months and with greater social competence at 24 months (Leerkes et al., 2009). In addition, parents’ difficulty with managing negative emotions might be more strongly associated with their responses to their infant’s distress than their responses to non-distress bids for play and exploration.

Regarding toddlers’ socioemotional outcomes, it might be more effective to use assessments other than parent-report including observations or teacher report measures. It could also be helpful to examine toddlers’ socioemotional outcomes at later ages, including preschool, elementary school years, and beyond. Studies could also measure toddlers’ socioemotional outcomes at an additional later time point, in order to determine the effect of these early socioemotional difficulties on longer term socioemotional functioning. Research could also look at toddlers’ outcomes in other domains like cognitive functioning.

Conclusion

In summary, this project examined whether maternal emotion dysregulation during pregnancy predicted toddler socioemotional difficulties. This project also examined whether maternal parenting sensitivity at least partially mediated the association between maternal emotion dysregulation and toddler socioemotional outcomes. Maternal emotion dysregulation was positively correlated with toddlers’ externalizing behavior problems, internalizing behavior problems, and dysregulation, but not with toddler competence. Maternal emotion dysregulation was not significantly correlated with maternal parenting sensitivity and parenting sensitivity was not significantly correlated with toddlers’ socioemotional problems, indicating that the indirect effect of parenting sensitivity on the relationship between maternal emotion dysregulation and toddler socioemotional outcomes was not significant. These findings contribute to developmental psychology by highlighting the role that maternal mental health may play on toddlers’ socioemotional outcomes during early child development. This research provides insights for interventions that support mothers’ emotion regulation, which may have implications for toddlers’ socioemotional outcomes.

References

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. N. (2015). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. New York:

Psychology Press.

Beauchaine, T. P., & Cicchetti, D. (2019). Emotion dysregulation and emerging psychopathology: A transdiagnostic, transdisciplinary perspective. Development and Psychopathology, 31(3), 799–804. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579419000671

Bernard, K., Meade, E. B., & Dozier, M. (2013). Parental synchrony and nurturance as targets in an attachment based intervention: Building upon Mary Ainsworth’s insights about mother-infant interaction. Attachment & Human Development, 15(5-6), 507-523. 10.1080/14616734.2013.820920

Bernard, K., Nissim, G., Vaccaro, S., Harris, J. L., & Lindhiem, O. (2018). Association between maternal depression and maternal sensitivity from birth to 12 months: A meta-analysis. Attachment & Human Development, 20(6), 578–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2018.1430839

Blandon, A. Y., Calkins, S. D., & Keane, S. P. (2010). Predicting emotional and social competence during early childhood from toddler risk and maternal behavior. Development and Psychopathology, 22(1), 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579409990307

Borairi, S., Deneault, A., Madigan, S., Fearon, P., Devereux, C., Geer, M., Jeyanayagam, B., Martini, J., & Jenkins, J. (2024). A meta-analytic examination of sensitive responsiveness as a mediator between depression in mothers and psychopathology in children. Attachment & Human Development, 26(4), 273–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2024.2359689

Brewer, S. K., Zahniser, E., & Conley, C. S. (2016). Longitudinal impacts of emotion regulation on emerging adults: Variable- and person-centered approaches. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 47, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2016.09.002

Bushman, B. J., Baumeister, R. F., & Phillips, C. M. (2001). Do people agree to improve their mood? Catharsis beliefs, affect regulation opportunity, and aggressive responding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 17–32.

Carreras, J., Carter, A. S., Heberle, A., Forbes, D., & Gray, S. O. (2019). Emotion regulation and parent distress: Getting at the heart of sensitive parenting among parents of preschool children experiencing high sociodemographic risk. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(11), 2953–2962. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01471-z

Carter, A. S., Briggs-Gowan, M. J., Jones, S. M., & Little, T. D. (2003). The Infant- Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (ITSEA): Factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31, 495–514. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1025449031360

Cooke, J. E., Deneault, A., Devereux, C., Eirich, R., Fearon, R. M. P., & Madigan, S. (2022). Parental sensitivity and child behavioral problems: A meta‐analytic review. Child Development, 93(5), 1231–1248. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13764

Daniel, S. K., Abdel-Baki, R., & Hall, G. B. (2020). The protective effect of emotion regulation on child and adolescent wellbeing. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(7), 2010–2027. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01731-3

De Campora, G., Giromini, L., Larciprete, G., Volsi, V. L., & Zavattini, G. C. (2014). The impact of maternal overweight and emotion regulation on early eating behaviors. Eating Behaviors, 15(3), 403–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.04.013

Dix, T. (1991). The affective organization of parenting: Adaptive and maladaptative processes. Psychological Bulletin, 110(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.3

Fenson, L., Marchman, V. A., Thal, D. J., Dale, P. S., Reznick, J. S., & Bates, E. (2007) MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories: User’s Guide and Technical Manual. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Frick, M. A., Forslund, T., Fransson, M., Johansson, M., Bohlin, G., & Brocki, K. C. (2017). The role of sustained attention, maternal sensitivity, and infant temperament in the development of early self‐regulation. British Journal of Psychology, 109(2), 277–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12266

Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2003). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:joba.0000007455.08539.94

Gross, J. J., & Muñoz, R. F. (1995). Emotion regulation and mental health. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice, 2(2), 151–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.1995.tb00036.x

Haga, S. M., Ulleberg, P., Slinning, K., Kraft, P., Steen, T. B., & Staff, A. (2012). A longitudinal study of postpartum depressive symptoms: multilevel growth curve analyses of emotion regulation strategies, breastfeeding self-efficacy, and social support. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 15(3), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-012-0274-2

Keenan, K. (2000). Emotion dysregulation as a risk factor for child psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice, 7(4), 418–434. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.7.4.418

Leerkes, E. M., Blankson, A. N., & O’Brien, M. (2009). Differential effects of maternal sensitivity to infant distress and nondistress on Social‐Emotional functioning. Child Development, 80(3), 762–775. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01296.x

Leerkes, E. M., Su, J., & Sommers, S. A. (2020). Mothers’ self‐reported emotion dysregulation: A potentially valid method in the field of infant mental health. Infant Mental Health Journal, 41(5), 642–650. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21873

Li, D., Wu, N., & Wang, Z. (2019). Intergenerational transmission of emotion regulation through parents’ reactions to children’s negative emotions: Tests of unique, actor, partner, and mediating effects. Children and Youth Services Review, 101, 113– 122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.03.038

Lin, B., Kaliush, P. R., Conradt, E., Terrell, S., Neff, D., Allen, A. K., … & Crowell, S. E. (2019). Intergenerational transmission of emotion dysregulation: Part I. Psychopathology, self-injury, and parasympathetic responsivity among pregnant women. Development and Psychopathology, 31(3), 817-831. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579419000336

Lindhiem, O., Bernard, K., & Dozier, M. (2010). Maternal sensitivity: Within-person variability and the utility of multiple assessments. Child Maltreatment, 16(1), 41– 50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559510387662

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive–behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press.

Mennin, D. S., Heimberg, R. G., Turk, C. L., & Fresco, D. M. (2002). Applying an emotion regulation framework to integrative approaches to generalized anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice, 9(1), 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.9.1.85

NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (1996). Observational Record of the Caregiving Environment. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 11(3), 269-306.

Rosenblum, K. L., Muzik, M., Jester, J. M., Huth‐Bocks, A., Erickson, N., Ludtke, M., Weatherston, D., Brophy‐Herb, H., Tableman, B., Alfafara, E., & Waddell, R. (2020). Community‐delivered infant–parent psychotherapy improves maternal sensitive caregiving: Evaluation of the Michigan model of infant mental health home visiting. Infant Mental Health Journal, 41(2), 178–190. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21840

Rutherford, H. J., Wallace, N. S., Laurent, H. K., & Mayes, L. C. (2015). Emotion regulation in parenthood. Developmental Review, 36, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2014.12.008

Teti, D. M., & Cole, P. M. (2011). Parenting at risk: New perspectives, new approaches. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(5), 625–634. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025287

Media Attributions

- Wulff_Thea_Spring_2025 -Figure1

- Wulff_Thea_Spring_2025-Table1