College of Humanities

56 The Marginalization of Non-Black Women of Color (NBWOC) in Media, Academia, and Professional Spaces

Alisha Ruiz

Faculty Mentor: Tracey Daniels-Lerberg (Writing & Rhetoric Studies, University of Utah)

Abstract

This paper will focus on how the marginalization of non-Black women of color (NBWOC) in media, academia, and professional spaces contributes to their underrepresentation in research centered on racism in the workplace. Analysis will be done by gathering research regarding textured hair focusing on only Black women, as well as research that includes all WOC. Both will be compared to focus on why NBWOC were not included in much of the research on the subject of racial discrimination in the workplace. Other sources will be used to prove, or disprove, that the exclusion of NBWOC in research centered on racism in the workplace for all WOC is a choice.

Introduction

Does the marginalization of non-Black women of color (NBWOC) in media, academia, and professional spaces contribute to their underrepresentation in research centered on racism in the workplace? This paper will use the phrase Women of Color (WOC) to define a group of people who self-report their gender as female and whose race or ethnicity is Hispanic; Black; Asian American; Native Hawaiian; Pacific Islander; American Indian/Alaska Native; or multiracial. Women of color presently report to experience race-based discrimination while in their workplaces. Whether it comes to their coworkers, superiors, or clients, this has become a universal experience for most women of color within America. Numerous articles, studies, and academic papers have been published expressing this issue. However, almost all have a similar misconception. They use WOC to refer to only Black women and not as the umbrella term it is. Recently the underrepresentation of WOC has been acknowledged in academia as well as research and authors have worked to enhance the visibility of WOC in media as well as professional settings. Unfortunately, most overlook a critical demographic when discussing WOC, women of color who are not Black. Intersectional invisibility is a concept that would describe the underrepresentation of NBWOC in research. In this paper, we will dive into this concept and how the marginalization of non-Black women of color (NBWOC) in media, academia, and professional spaces contributes to their underrepresentation in research centered on racism in the workplace. The lack of representation and acknowledgment of non-Black women of color not only diminishes their presence in professional and social arenas but also perpetuates stereotypes and biases that affect their access to opportunities and their capacity to influence change in research as well as their daily lives.

Literature Review

Examining one of the many articles discussing a Black woman’s experience with textured hair (when the intended focus was WOC) it becomes clear that the reason for excluding WOC, when NBWOC are present in the data, often stems from the researcher’s failure to recognize that NBWOC can also have textured hair. The article, Hair Matters: Toward Understanding Natural Black Hair Bias in the Workplace suggests that Black women are only cast for lead roles or “good/heroic characters” if they have long straight hair and Eurocentric features1. The author identifies actresses like Kerry Washington, Taraji Henson, and Nia Long as people who have openly expressed this distasteful truth about Hollywood and the media. In contrast, characters who portray negative stereotypes are cast with natural Afrocentric hairstyles. However, we are beginning to see more and more exceptions, an example it provided was Black Panther, where the actors were allowed to wear their natural hair for accurate representation (Dawson, 2019). This article gives a connection that negative connotations towards Black women who wear their natural hair are still seen within work environments and its source is the media portraying this negative opinion. The authors do not provide examples of how textured hair is viewed in spaces that are also composed of NBWOC in their analysis of media representation. The paper then moves onto their primary data, which is collected from anonymous commenters on articles about natural hair. While many commenters suggest they identify as Black, others are vague and only share their experience/opinion on having natural hair. The authors do not confirm that all their respondents were Black, nor did they acknowledge that NBWOC can also have textured hair. As a result, the only certainty is that the commenters had textured hair, not that they were Black. This highlights a critical oversight in terminology—WOC or POC would have been more appropriate than “Black,” given that NBWOC (or possibly White women) with textured hair were included in the data collection.

Next, we will observe an article that includes all WOC in its interpretation and why their insight is valuable in moving forward with research regarding NBWOC. Hair We Grow Again: Upward Mobility, Career Compromise, and Natural Hair Bias in the Workplace, believes that how a WOC feels about her natural hair in the workplace is due to self-reflection and how the woman sees herself with her natural hair (Summers, 2022). The author also believes that when the woman is confident in how she feels about her natural hair, this will impact how she thinks others feel about her hair. This can be important in continued research, because it brings up the idea that, when we do surveys about how women feel about their hair, it is going to depend/vary if it is based on self-reflection. The author also mentions that women will pick their career choices wisely based on their previous experiences so that discrimination does not happen again (Summers, 2022). This can also impact data collected by showing that a woman could now be content at her place of work based on her previous decisions to avoid discrimination. The author argues that WOC might feel pressured to change their career aspirations if they believe their natural hair may limit advancement opportunities (Summers, 2022).

This is a strong example of how the experiences of NBWOC and Black women can provide insight into the racial discrimination faced by all women of color and how including all WOC in analysis can be beneficial for future research.

These sources can work with each other in terms of what needs to be collected for data (what’s useful to know and what’s not). The first paper presents data on women with textured hair but limits its interpretation to Black women. In contrast, the second paper examines women of color more broadly, offering a more inclusive perspective on WOC’s experiences.

Another suggestion is that the CROWN Act and other political interference have an important impact on how women of color and their coworkers see their natural hair. The authors in Hair We Grow Again: Upward Mobility, Career Compromise, and Natural Hair Bias in the Workplace mentioned that the Civil Rights Act of 1964(Title VII) prohibits discrimination based on race, sex, color, religion, or national origin, intended to improve equity for African Americans and women of color. This has allowed companies to enact policies to prevent discrimination. However, something more specific was needed for natural hair. This is when the CROWN act comes into play. The CROWN Act—Create a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair—is designed to protect people of color from race-based hair discrimination in workplaces and schools. It aims to eliminate biases that may restrict opportunities based on hairstyles (Summers, 2022). Although, since the CROWN act, we have seen a rise in companies advertising a zero-discrimination zone, we have now seen new and different methods of discrimination. A study that supports this new era of discrimination is the Dove CROWN act study. This study was done by the JOY Collective and Dove in 2019, and they found that Black women are significantly affected by appearance-based biases. For instance, Black women are 1.5 times more likely to be sent home from work due to their hair and are 30% more likely to be made aware of formal workplace grooming policies. These statistics suggest that natural hair can negatively impact career advancement for Black women, but not NBWOC. With this new information in mind, we see now that although laws are in place, coworkers, clients, and bosses have now found new methods to continue what the CROWN act tries to get rid of.

Both ideas should be kept in mind when thinking about an individual’s workplace and what representation of anti-discrimination that a company presents to its workers. It also brings into consideration whether these policies are being upheld in the field of work.

Using the above ideas, we can connect interpersonal beliefs and environmental impacts, as well as political influences to how a woman of color, as well as their colleagues, can feel about their natural hair. Black women’s hair and natural hairstyles in the workplace: Expanding the definition of race under Title VII expands on the idea of how when someone goes in for an interview, they are often instructed to be themselves. However, unconscious or implicit bias influences how they are evaluated in the workplace. While they’re encouraged to be authentic, they may not realize that this “authentic self” is often measured against a standard (straight, white men) (Tchenga, 2021). Straying from this norm can create challenges in the workplace or even cause the worker to be a liability. To access key networks and promotion opportunities, one must be seen as fitting into the dominant workplace culture (Tchenga, 2021). Moreover, others’ perceptions of them impact evaluations of non-visual traits, such as their perceived competence or professionalism. How a boss/supervisor or coworker sees a person of color as professional is entirely up to what they believe is professional or not. These morals/beliefs can be impacted by media and/or external factors. A common experience to come across is making a white colleague “uncomfortable”, and this prevents the worker from being accepted by their new workplace. Hence, women of color are motivated and/or pressured to achieve the looks of their white counterparts (Tchenga, 2021). This article, however, is centered on Black women, but can also be applied to WOC. The author agrees that not all of what Black women experience is the same as WOC. The author does, however, support the idea that textured/natural hair-based discrimination isn’t limited to Black people and encourages us to look further into other POC to understand their experiences as well.

In reviewing the literature on women of color wearing their natural hair in the workplace, some researchers argue that how a woman experiences discrimination is influenced by the media, while others demonstrate it is their own personal beliefs as well as environmental factors that allow them to interpret their interactions, and still others believe that both can and do exist and that political influences can also have a say in their experience as well. All factors should be included when determining how a woman of color goes through their career with their natural hair. There are plenty of outside factors such as her family’s personal beliefs, the political influence that has power over the company she works at, self-reflection, as well as what her colleagues were made to believe is acceptable that influences her experience at work while wearing her natural hair. These factors have all shown particular importance in a WOC’s career based on the literature reviewed. The researchers seem to disagree or overlook whether NBWOC should be included in the area. While some focus specifically on Black women (despite using the term WOC), others include all WOC. The major issue with whether they should be included is the way we interpret their experiences. Black women, simply put, do not experience the same treatment as NBWOC. They are still dehumanized and considered the opposite of America’s beauty standards, while NBWOC are given more opportunities as well as a higher quality of life. Though, despite this difference, both have textured hair and experience racial discrimination. Importantly, this similarity is not enough for their experiences to always be grouped together and should inspire us to look at different forms of interpretation when looking at their data.

Inclusion of NBPOC in POC studies and its Impact

The company, StyleSeat, conducted a survey of 1,252 Americans about “their thoughts on natural hair in the workplace and what people of color have experienced as a result of wearing their natural hair” (StyleSeat, 2023). They discovered that 54% of POC feel discriminated against for wearing their natural hair. They also discovered that 60% of POC and 51% of white people say they “think people are discriminated against at work for natural hairstyles linked to racial identity” (StyleSeat, 2023).

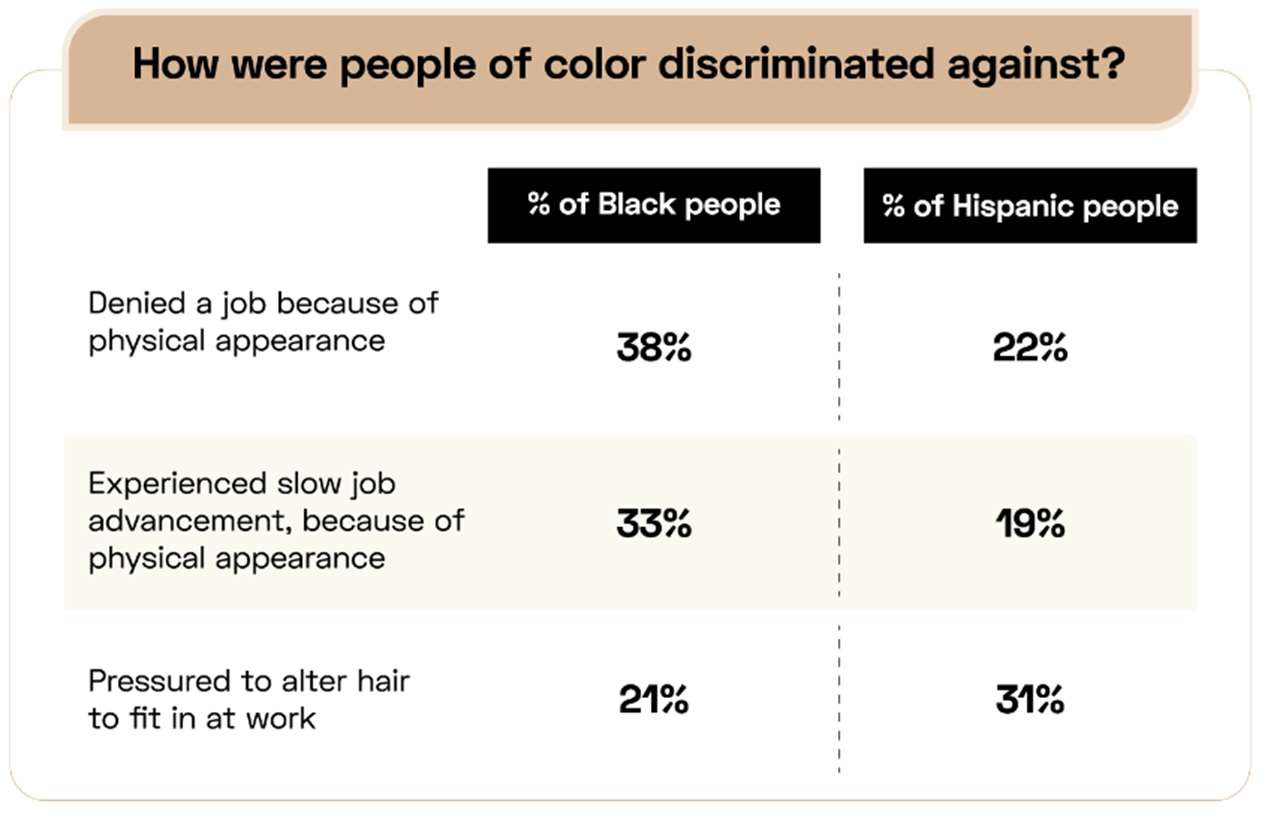

This study includes all POC but focuses on Black women as well as Hispanic women. Figure 1 describes the percentage of respondents who experience a specific situation of workplace discrimination due to their appearance.

Figure 1. Tabled results of StyleSeat’s survey about the thoughts on natural hair in the workplace and what people of color have experienced as a result of wearing their natural hair for Americans.

Figure 1. Tabled results of StyleSeat’s survey about the thoughts on natural hair in the workplace and what people of color have experienced as a result of wearing their natural hair for Americans.

This survey provides valuable insight into the broader scope of experiences that could be represented in research results and analysis if studies were to include all people of color (POC), rather than focusing exclusively on Black Americans. By incorporating the diverse experiences of other POC communities, the survey demonstrates that we gain a more nuanced understanding of what it means to be a person of color in modern America. Such inclusiveness in research not only enriches our perspective but also avoids the limitations of a narrow demographic focus. Furthermore, this approach exemplifies the importance of categorizing data accurately, ensuring that individual experiences are neither overlooked nor generalized under broad labels. This careful differentiation allows for a more comprehensive and respectful portrayal of the varied realities faced by POC in America. In Figure 2, Dr. Berdahl also shows using Black women as well as NBWOC and refers to them as “Minority Women” (Berdahl, 2006).

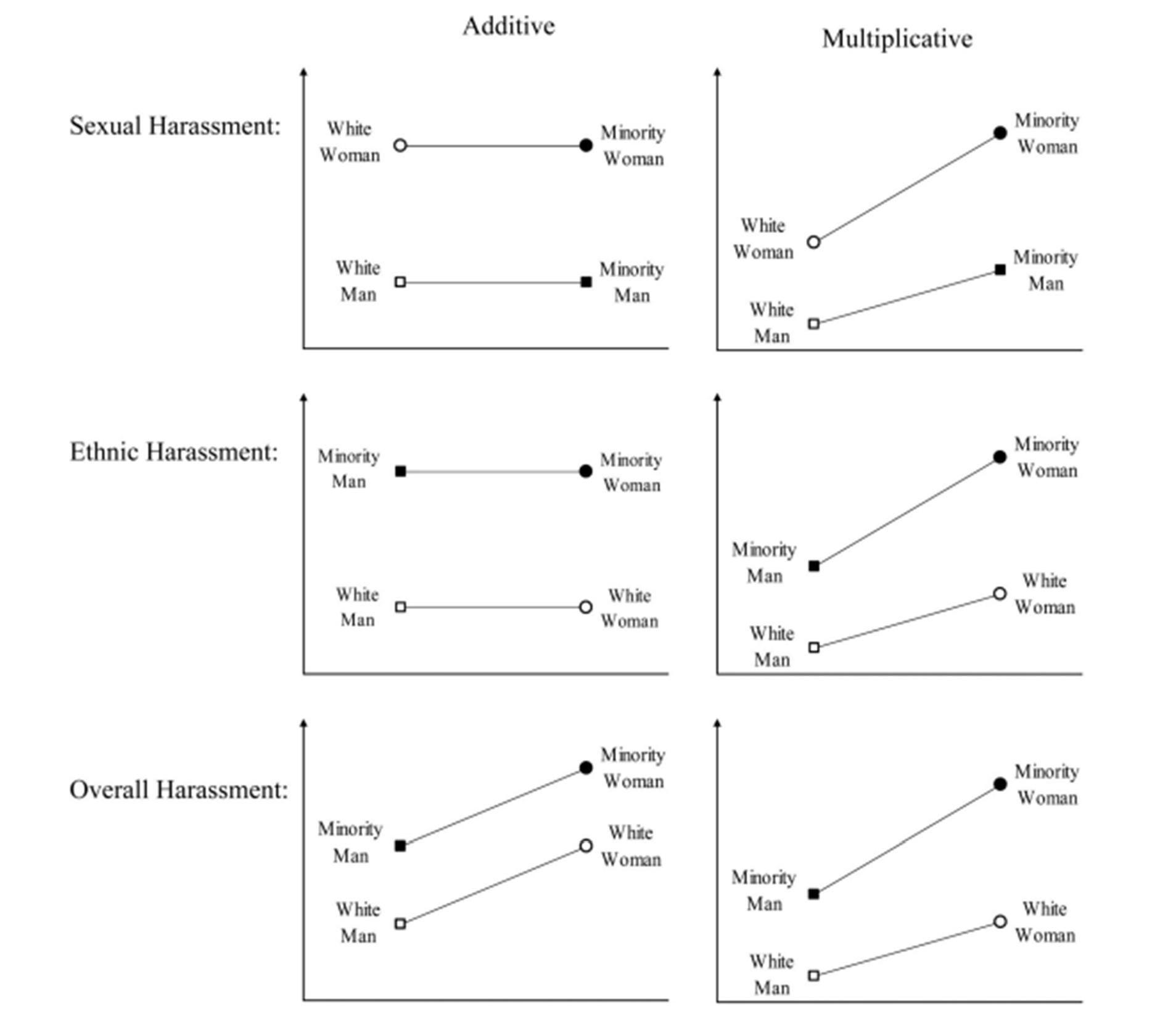

Figure 2. Predictions made by the additive and multiplicative versions of the double jeopardy hypothesis stated in Workplace harassment: Double jeopardy for minority women.

This data shows us that “Minorities experience more ethnic harassment than Whites, and women experience more ethnic harassment than men” (Berdahl, 2006). Berdahl makes a point to show that all WOC should be included in research such as this as it makes a stronger argument that racism still exists in the workplace.

The Root of Exclusion of NBWOC in Research

Although the previous articles support the idea that Black women are of importance when it comes to experiences of WOC in workplaces, Dr. Nimisha Barton suggests that the reason NBWOC are not represented well in research is because they often express that their “racial identity simply hasn’t shaped their lives or worldview” (Barton, 2022). This can be impactful when it comes to WOC filling out surveys and the researchers only find that Black women have sufficient evidence that proves discrimination within the workplace. This is only because they do not have a choice. This is connected to POC who are white-passing or white-adjacent. POC with Eurocentric features experience less discrimination than POC who are not white-passing. Barton emphasizes that “It is high time that we acknowledge and reconsider how we as white-passing and white adjacent people of color participate in the project of white supremacy in our workplaces” (Barton, 2022). This information tells us that Black

women are often emphasized when it comes to WOC because their experiences are more straightforward compared to NBWOC. NBWOC are reported as not confident that what they experience is tied down to their race/ethnicity, and this often prevents them from giving definitive answers in response to surveys.

Choosing to be a POC is a Privilege

Being able to choose whether you are a POC is a privilege that Black people are not given access to. This could be a possible explanation why NBWOC aren’t included in studies about women who identify as WOC. Barton further explains “white-passing people of color may visibly “pass” as white. They thus experience entry into the white world on account of certain phenotypic characteristics, and skin color above all. But white-adjacent people of color like myself, though quite visibly nonwhite, may nevertheless occasionally become insiders in the white world as a result of two separate but related factors” (Barton 2022). Black women are not given the option (or privilege) to not identify as WOC, so it is no wonder that they are the primary source for a WOC’s experience in the workplace. In Prisha’s TedTalk, Inhaling Anti-Blackness, Exhaling Liberation, she discusses how Black women are tired of being referred to as WOC and not Black women. She emphasizes that not only can this cause another group of people to be offended, but it offends Black women because they are labeled incorrectly. She states that by not using the term “Black”, we are avoiding the conversation that no one will listen to what we have to say if we are talking about Black people. We are avoiding the conversation of how Black people, and their experiences make some of us uncomfortable. This is unacceptable. She says that we can stand against this if we only use WOC and Black women when appropriate (Prisha, 2022). This will help NBWOC gain visibility in society while also charging towards uncomfortable conversations of preventing and destroying anti-blackness.

Conclusion

NBWOC must be represented within research about WOC without overlooking the experiences of Black women. It has been seen that instead of authors using the term WOC to describe Black women, they use African American women or Black women to express their findings on Black women’s experiences. This has been deemed appropriate and is the best term (according to Black women) for them to be referred to as. Although it is critical to represent Black women in a field where they have previously been misrepresented or ignored, it is also critical that this past method is not continued for NBWOC in research as well. This can be avoided by stopping the misuse of the word WOC and/or including NBWOC in studies or surveys conducted for research centered on WOC. Dr. Nimisha Barton also suggests that for all WOC to be included in the research, NBWOC should start referring to themselves as WOC as well. “The first step is to recognize that never or even just rarely being made aware of your racial identity is, in and of itself, a sign of just how white passing and/or white adjacent you are” (Barton, 2022). Once you recognize yourself as a POC, you can combat anti-blackness within our society and finally allow your experiences to be included in research. Furthermore, it will emphasize the importance that Black women are women of color, but women of color are not Black women. This is important in preventing the harm of WOC as well as helping the visibility of WOC in research, academia, and professional settings.

Footnote

1. Eurocentric features are defined as straight and light hair, large blue or green eyes, a small nose, or light skin tone (Dawson, 2019)

Bibliography

Barton, N. (2022, December 28). Proximity to Whiteness: Anti-Blackness, People of Color, and the Struggle for Solidarity — Nimisha Barton, PhD. Nimisha Barton, PhD. https://www.drnimishabarton.com/redacted/proximity-to-whitenessnbspanti-blackness-people-of- color-and-the-struggle-for-solidarity

Berdahl, J. L., & Moore, C. (2006). Workplace harassment: Double jeopardy for minority women. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 426–436. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.2.426

Bowleg, L. (2012). The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality—An important theoretical framework for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 1267– 1273.

Dawson, Gail A., Katherine A. Karl, and Joy V. Peluchette. “Hair Matters: Toward Understanding Natural Black Hair Bias in the Workplace.” Journal of leadership & organizational studies 26.3 (2019): 389–401. Print.

Francis, Kula A., and Anna M. Clarke. Women of Color and Hair Bias in the Work Environment. 2023. Print.

Greene, D Wendy. “Splitting Hairs: The Eleventh Circuit’s Take on Workplace Bans Against Black Women’s Natural Hair in EEOC v. Catastrophe Management Solutions.” University of Miami law review 71.4 (2017): 987. Print.

Sesko, A. K., & Biernat, M. (2018). Invisibility of Black women: Drawing attention to individuality. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 21(1), 141–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430216663017

StyleSeat. (2023, May 15). 46% of people of color say employers could do more to decrease hair discrimination. StyleSeat Pro Beauty Blog. https://www.styleseat.com/blog/natural-hair- discrimination-at-work/

Summers, LaTonya M., Tonya Davis, and Bilal Kosovac. “Hair We Grow Again: Upward Mobility, Career Compromise, and Natural Hair Bias in the Workplace.” The Career development quarterly 70.3 (2022): 202–214. Print.

Tchenga, Doriane S Nguenang. “Black Women’s Hair and Natural Hairstyles in the Workplace: expanding the Definition of Race Under Title VII.” Virginia law review 107 (2021): 272–299. Print.

The official CROWN Act. (n.d.). The Official CROWN Act. https://www.thecrownact.com/

Women of color – women in the states. (2015, June 1). Women in the States. https://statusofwomendata.org/women-of-color/#spotlighteewoc