In 2020, an estimated 10 million deaths worldwide occurred due to cancer (Sung et al., 2021). As lower and middle income countries experience demographic changes, noncommunicable diseases like cancer will become more prominent in the disease burden (Sung et al., 2021; Ward & Goldie, 2024). The global cancer burden is projected to be 28.4 million cases in 2040, with an increasing share of those cases occurring in LMICs ((Sung et al., 2021). Cancer deaths in LMICs are expected to account for approximately three-quarters of all cancer deaths in 2030 (Pramesh et al., 2022). Cancer patients in LMICs face various barriers to care due to limited public awareness of cancer and inadequate healthcare infrastructure (Anandasabapathy et al., 2024). Multiple studies in LMICs demonstrate there are widespread myths and misinformation about cancer, including the idea that cancer is contagious, that it is untreatable, or can be treated by alternative medicine (Ajith et al., 2023; Bamodu & Chung, 2024; Banning & Hafeez, 2009; Ezeome & Anarado, 2007). Essential medical technology such as imaging, pathology services, and radiotherapy are limited in availability across LMICs, with radiotherapy unavailable in 55 LMICs (Datta et al., 2014). Limited capacity due to lack of technology and inadequate oncology workforce result in limited screenings and delays in diagnosis (Anandasabapathy et al., 2024; Pace et al., 2015). Treatment abandonment is common due to community misbeliefs that drive cancer stigma, as well as costs of treatment.

Social support can be defined as the “perception and actuality that one is cared for, has assistance available from other people, and that one is part of a supportive social network” (House et al., 1988). Historically, the term “social support” was used broadly to describe various aspects of social relationships, but distinctions between different terms have since been clarified in literature. Social integration and social networks are often used to describe the quantity of ties an individual has and the structure of those ties, while social support is used to describe the functional and qualitative aspects of social relationships, including the content and functions of these relationships (House et al., 1988; Muñoz-Laboy et al., 2014; Taylor, 2012).

They were like, ‘No. We know that breast cancer especially affects people who are 50 years and above and you are just…’ that time, I was just 31 [years old]. ‘How is that possible? No way! You are too young to have cancer,’ and also they were like, ‘look at your breast, it is just fine. ’(female, 35 years old, breast cancer)

Instrumental Support at Diagnosis

Instrumental support at this stage co-occurred with informational support for some survivors when members of their social network worked in healthcare, which gave them knowledge as well as access to practical resources. One survivor received medicine to treat her symptoms from her sister’s friends, who worked at a hospital. Another survivor had a friend who was able to give him an x-ray.

I have a friend at Nkhotakota hospital and I went to Nkhotakota so when he x-rayed me he said, ‘This is a swelling that does not have any pus, so in this condition, I cannot do anything, but I will give a referral letter to Kamuzu Central Hospital.’ (male, 38 years old, lymphoma)

Other instances of instrumental support involved supporting transportation costs or giving someone a place to stay so that the survivor could be seen by a doctor at a tertiary level hospital, and advocating for the patient to receive biopsy results in a timely manner.

He [brother] pushed…they said that in December there is a holiday and it was not possible to do the procedure but after my brother had pushed it worked and I was diagnosed. (female, 46 years old, lymphoma)

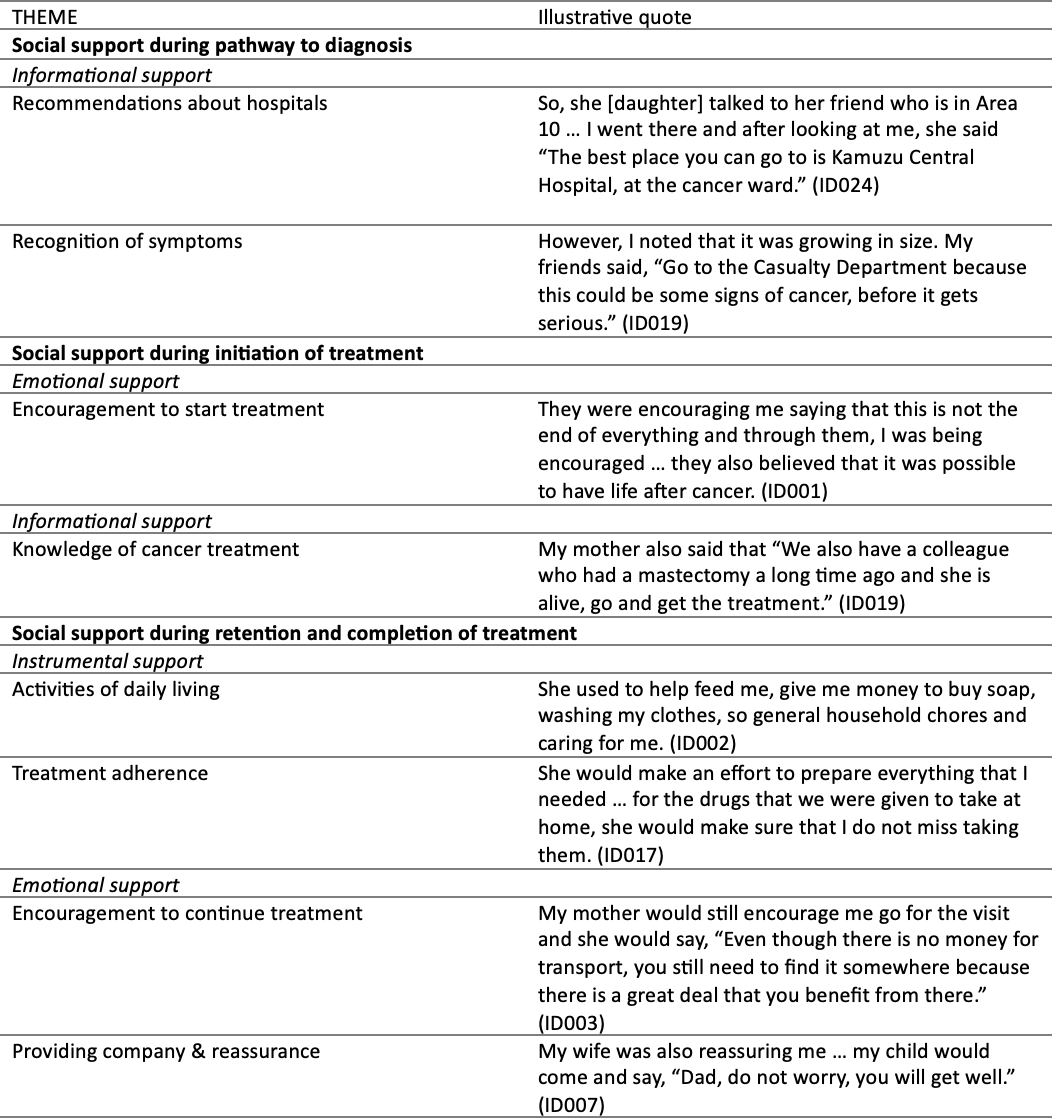

Social Support at Initiation of Treatment

At the stage after diagnosis up to initiation of treatment, emotional support was most common.

This came in the form of encouragement from family members and friends to start treatment, and in one case, encouragement from a cancer survivor. In some cases, emotional support co-occurred with informational support, as family members encouraged patients to begin treatment based on knowledge of survival chances or cancer survivors. There were also some instances where informational support provided was based on misinformation. Instrumental support did not emerge at this stage.

Emotional Support at Initiation of Treatment

Instances of emotional support at this stage involved encouragement from friends and family members to begin treatment. These involved expressions of support such as prayers, as well as reassurance that the patient can survive their diagnosis through adherence to treatment.

When my relatives got to know that I had breast cancer, they urged and reassured me, especially my mother, she was the first one I disclosed to, and she encouraged me very much and she said, ‘Do not worry, there are drugs that cure that illness. The hospital which diagnosed your cancer is in a position to start the process to treat your breast cancer and you are going to be healed.’ These were the first words that my mother told me. (female, 42 years old, breast cancer survivor)

In many cases, emotional support came in the form of sharing information. This took place when caregivers and other members of the survivor’s social support network encouraged them to begin treatment based on evidence of the efficacy of cancer treatment, either through trust in the medical system or personal knowledge of cancer survivors.

So when I went home and explained to my husband, he reassured me by saying, ‘Do not worry, do not decline the medication … Go and receive the medication, because there are so many people out there whom we heard that they had surgery or received the treatment and they got well.’ (female, 38 years old, breast cancer)

Informational Support at Initiation of Treatment

In some cases, informational support discouraged patients from pursuing medical treatment at the hospital. One survivor said she was told by people in her community that cancer medication would make her sicker than she already was, while other patients said that people in their community recommended they see traditional healers.

I remember this other time, my maid said, ‘You should come to our church! I told people in our church that you were not feeling well but they said you were ill, but not in that context but it was witchcraft.’ (female, 32 years old, lymphoma)

Social Support at Retention & Completion of Treatment

At the stage of retention in treatment, all three forms of support emerged, but instrumental support and emotional support appeared to be significant. There were some cases where instrumental and emotional support co-occurred. The most common form of instrumental support was assistance with activities of daily living such as bathing, mobility, cooking food, and chores around the house. Emotional support came in the form of encouragement from family, friends, and sometimes other people in the community to continue treatment. This was often provided from other cancer survivors who patients interacted with at the hospital. One common type of informational support during this time was dietary recommendations from friends and family to boost immunity.

Emotional Support at Completion of Treatment

Survivors described receiving emotional support in the form of encouragement to continue treatment, as well as through companionship, comfort and reassurance. Some survivors mentioned receiving encouragement from fellow cancer patients who finished treatment.

We would be encouraged by friends who came for the checkup and they also gave their testimonies, ‘I was also like you are, even worse, but look at me now!’ So little by little, the worries were reduced. (male, 50 years old, lymphoma)

Family members were mentioned often as a source of emotional support, providing companionship to survivors and making them feel loved and reassured during the completion of treatment.

I told that other sibling that she should remember me in my prayers because I was ill. Then she said, ‘You should not worry, we will be praying for you. I will be coming to you so that we should be encouraging each other.’ She helped me quite a lot because she used to come to our house every Sunday and she would pray for me and reassure me. As a result, the worries that affected me…gradually started to ease. (female, 32 years old, lymphoma)

Instrumental Support at Completion of Treatment

Almost all survivors discussed instrumental support from caregivers at the retention and completion stage as part of their narrative. These forms of support often co-occurred with emotional support, either explicitly by encouraging the survivor to adhere to treatment or implicitly by making them feel loved and cared for. A common form of instrumental support was assistance with activities of daily living including bathing, mobility, and household chores like cooking. This assistance was necessary given the side effects that patients experienced from treatment, such as fatigue and weakness.

My wife was caring for me in many ways, even when going to the clinic. She was the one holding me, bathing me, pushing me around on a wheelchair. All these were done by my wife. (male, 50 years old, lymphoma)

Cooking and feeding food were mentioned by several survivors, which was often a challenge due to nausea and vomiting experienced during treatment.

She [his partner] was taking good care of me … She was making sure that she gives me things even when I did not want them… For instance I have said that I was not having good appetite… she was making sure she finds food that I used to like when I was not sick and she was encouraging me that everything is going to be alright. (male, 50 years old, lymphoma)

Some survivors who were caretakers also received instrumental support in the form of childcare, with one survivor having assistance from her parents and siblings to take care of her son. It was also common for survivors to receive financial support from family members, both to manage the costs of attending treatment and also to supplement lost income. Another common form of instrumental support was providing transportation and accompaniment to appointments at the hospital.

Several survivors described treatment as an unpleasant experience due to the amount of medication which had to be taken, as well as the sometimes painful and time-consuming nature of chemotherapy. For these patients, instrumental support, combined with emotional support, helped them adhere to treatment through reminders and insistence to take medications and avoid missing appointments.

Well for her [wife] during my treatment, I think…there was a time when I got tired of the drugs. You would take 30, 35 [pills] at once…so I feel my wife was tough and would force me to take the drugs, because there was a time I used to refuse to take them. (male, lymphoma survivor)

One unique form of instrumental and emotional support at the retention and completion phase experienced by two survivors was family planning decisions. One survivor, when advised by his provider to avoid sex or engage in family planning due to possible birth defects from the cancer treatment, said his wife decided to undergo tubal ligation. The other survivor and his partner agreed to abstain from sex while he received treatment.

Informational Support at Completion of Treatment

Though informational support emerged less often at this stage compared to the other forms of social support, it did emerge. The most common instances of informational support were advice about the patient’s diet during treatment and advice to adhere to medication without missing any appointments. Survivors said they received many recommendations from relatives and other members of the community about what foods to eat to boost their immunity during cancer treatment. In some instances, this co-occurred with instrumental support, with friends and family bringing foods they perceived to be nutritional and beneficial to the patient.

So he [relative] was aware that the type of medication we were receiving was the same as TB in terms of nutrition needs. So he used to bring me some different types of foods … milk, eggs, Sobo [some local juice], margarine, things like those, he also brought me … some instant porridge flour … Without this, I do not know how my life was going to turn out to be. (female, 52 years old, lymphoma survivor)

Some survivors received advice from friends and family to adhere to treatment without missing any doses. In some instances, friends and family had contact with health professionals who were knowledgeable about cancer treatment and could be a source of information.

He [father] was working in accounting, but he was working with doctors at the clinic, he had other colleagues there whom he could go and ask questions on what we could do. (male, 45 years old, lymphoma survivor)

While these survivors received informational support that was helpful, other survivors received advice that was not helpful. Some survivors received advice from members of their community to avoid cancer treatment, suggesting alternative medicine instead because “the cancer drugs are not good.” Some advice was based on misinformation, for example the idea that cancer is an infectious disease that could be spread to others.

At times they would tell my husband that, ‘When you have sex with your wife, you will get infected with cancer.’ (female, 42 years old, breast cancer survivor)

Opportunities for Interventions

Multiple patients suggested it would be helpful for people newly diagnosed with cancer to meet cancer survivors. For some patients, speaking with cancer survivors or fellow patients was a source of encouragement that influenced their decisions to initiate or continue treatment. Many patients said they themselves would be willing to speak to newly diagnosed cancer patients to provide this encouragement. Patients also mentioned that people should be told about the realities of treatment, including side effects, and that it can be helpful to speak to other cancer patients to get advice and learn from how they are managing treatment and side effects.

As a cancer survivor, I would tell the cancer patients or those on treatment that they should not worry, they will be fine and that I have experience and, ‘Look at how I am,’ things like those. And personally, I would be happy if you can call me at any time so that I should come and sensitize these people so that they should be encouraged. I have been cured because other people gave me advice. (female, 41 years old, breast cancer survivor)

Several patients identified instrumental support needs including assistance obtaining nutritious food, money to cover costs of transportation, and ensuring the availability of medication at the hospital. Financial support to afford food and transportation were commonly identified by patients as an opportunity for intervention, with some patients complaining that although they received advice about which foods to eat during treatment, they could not afford these foods.

Sometimes you are told to take fruits, juices. Such things for us, the less privileged, are hard to come by…people on active treatment should be assisted with some food supplements…medicine is available at the hospital, but it is the food that is a challenge once the patient goes home. (female, 41 years old, breast cancer)

Other patients mentioned that although some monetary support for transportation is provided, it is often not adequate to cover the costs for patients who are living far away. Related to this, some patients suggested that accommodations should be made to allow patients a place to stay overnight while receiving treatment so that travelling time does not prevent adhering to treatment.

I observed that many people were coming from far, and this caused them to miss their appointments, I would feel sorry for them…most did not have relations in town so they could get to KCH, spend a night there so that they could start treatment the following day…people would come and they have nowhere to sleep. (male, 45 years old, lymphoma)

Patients also indicated need for informational support interventions including: community- level education to combat misinformation and promote early identification of symptoms, and medical advice to manage side effects during treatment.

In communities, people are suffering from different types of swellings. If they go to the hospital and are tested for cancer, they can be assisted in time. But because they are not aware that certain types of swelling can be cancer, so they just live with them or else, they waste time looking for alternative type of treatment, like traditional healers and the rest. (male, 23 years old, lymphoma)

Gender Differences

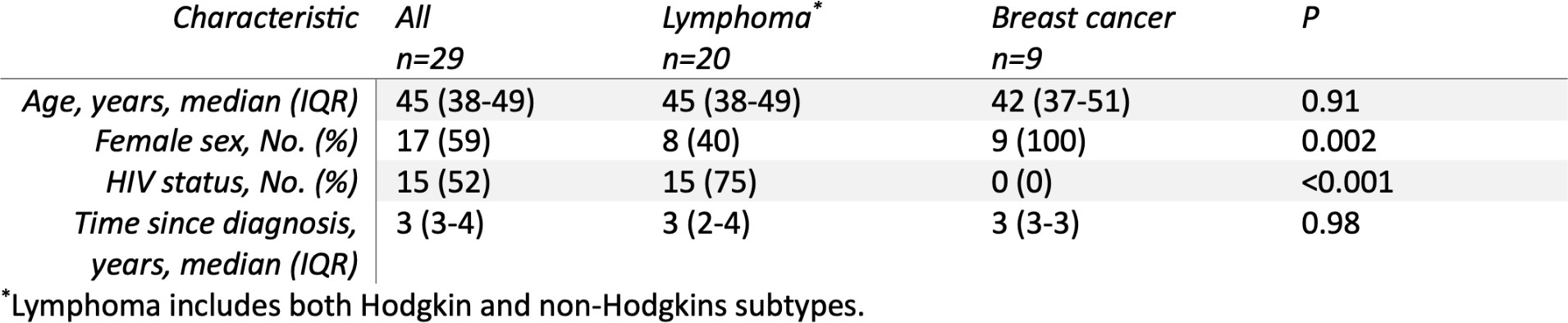

Social support needs across the cancer care continuum for men and women did not appear to differ. Considering that men were underrepresented in the sample, the emergence of informational, emotional, and instrumental support was similar between the two groups at the stages of diagnosis, initiation, and completion of treatment. The only point at which men reported lower levels of support was informational support at the stage of retention and completion of treatment, which was present overall at low levels. Although the amount of support did not differ, the sources of support sometimes did. The majority of the male survivors named their wife or partner as their primary caretaker and source of emotional and instrumental support, while most female survivors did not name their husband or partner. Instead, female survivors more commonly named female family members as their primary source of support. Most often, this was sisters, followed by mothers, daughters, and sisters-in-law.

Both men and women commonly reported more than one family member who contributed to social support, including parents and siblings. Both men and women named cancer survivors and patients receiving treatment at the same time as sources of emotional support. Overall, friends who were not relatives and not cancer survivors were not frequently mentioned, but were mentioned more often by women.

I was being encouraged, because you have friends who encourage you, they pray with you. So when people were encouraging me, I thought, ‘All these people cannot be just talking about one thing [for nothing], let me make a choice.’ (female, 38 years old, breast cancer survivor)

DISCUSSION

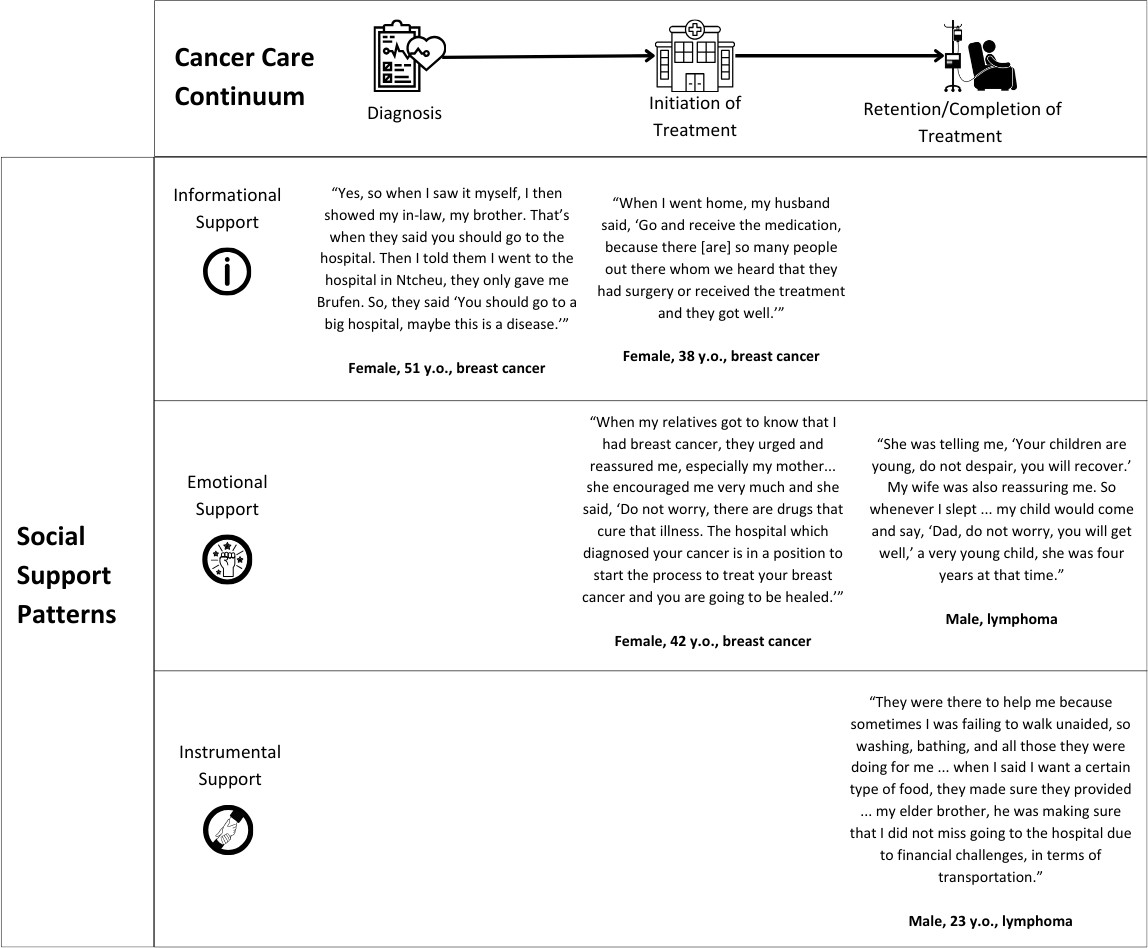

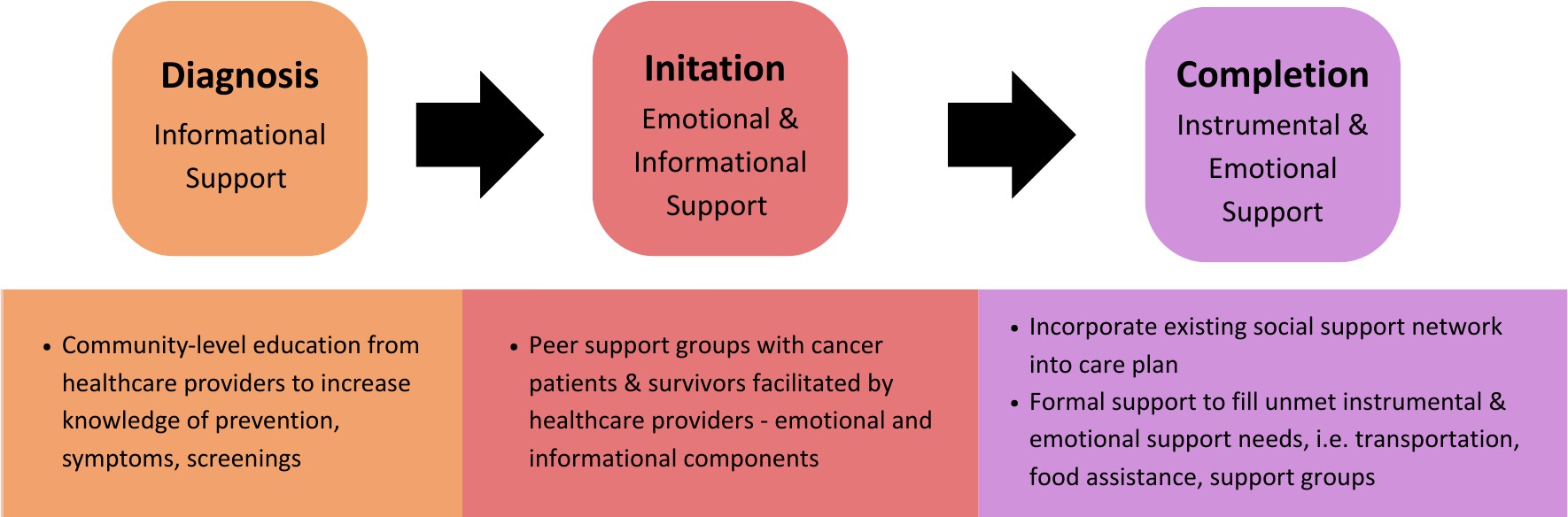

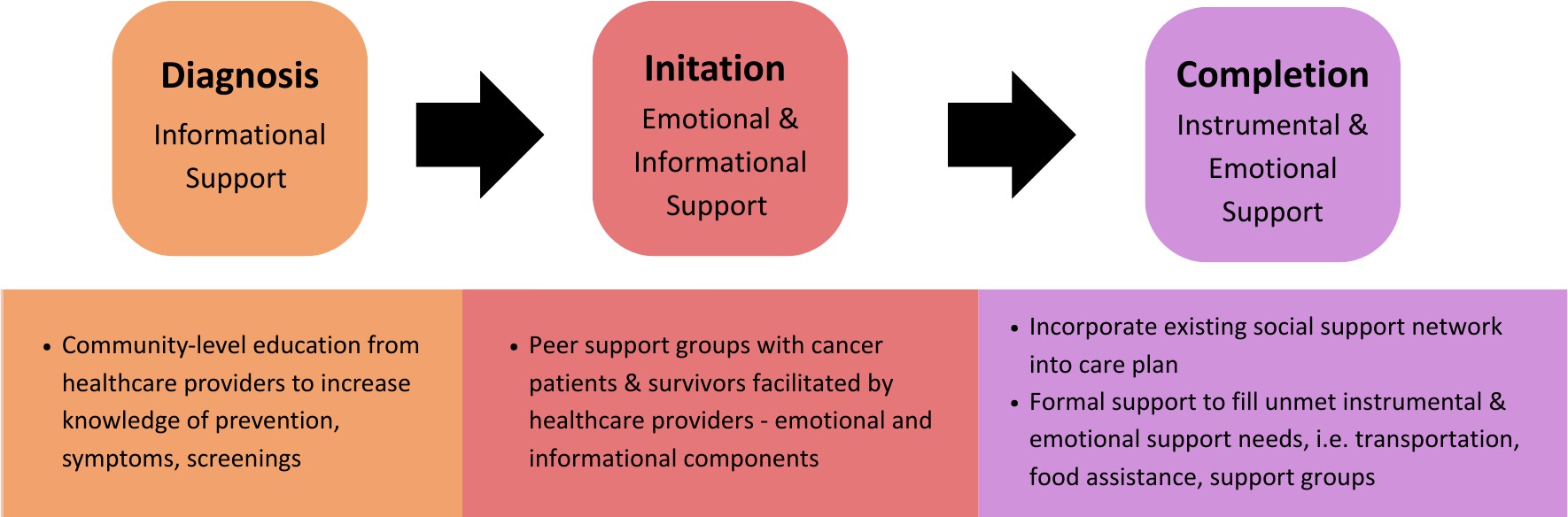

The results demonstrate that social support was an important facilitator to help patients move successfully across the cancer care continuum and into survivorship. The types of social support received by cancer patients fluctuated across the cancer care continuum. While informational support was critical at the diagnosis stage, emotional and informational support was needed at the initiation of treatment stage, and instrumental and emotional support was needed in the retention and completion stage. As the interviews come from a sample of survivors, it should be noted that these sources of support were resources that allowed people to complete cancer treatment and reach the stage of survivorship. Other cancer patients may have lacked these forms of support, contributing to their inability to complete treatment. This is something we are unable to examine in the present study. However, even though survivors received social support, it is possible they may have still had gaps in certain types of social support at various points along their cancer journey. Knowledge of the social support needs at each stage of the cancer care continuum can be used to create more effective, targeted interventions. Possible interventions to address social support needs for cancer patients in Malawi are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Intervention Opportunities to Address Social Support Needs Across the Cancer Care Continuum

Informational support appeared most significantly at the stage of diagnosis but also appeared at initiation and retention of care. In LMICs, it is common for patients to present with advanced stages of cancer due to barriers to diagnosis, including delayed recognition of symptoms, presentation to healthcare, and receipt of diagnostic services (Brand et al., 2019). The informational support identified at this stage appears to help close the gaps, with friends or family recognizing the severity of symptoms and giving them advice to present to hospitals that are equipped to diagnosis them. An effective intervention to address the need for informational support at diagnosis could be education to promote greater community-level awareness of cancer, including screening tools, recognition of symptoms, and where diagnostic technology is available. A review of interventions to provide cancer patient education in LMICs found that studies have most frequently included technology-based interventions such as videos or apps, followed by pamphlets or posters, written materials, education sessions over phone calls, or group education sessions, with most studies reporting improvements in the outcomes being measured (Christiansen et al., 2023). In a study in Korea, community-based interventions including posters, phone calls, and small group educational sessions were effective in decreasing belief in myths about breast cancer and increasing intention to undergo a mammography (Park et al., 2011). These strategies could be effective in increasing knowledge of cancer symptoms and diagnosis in Malawi, though instrumental support is still needed for patients to access hospitals, and infrastructure is needed to complete timely screenings and diagnosis.

It should be noted that not all informational support received by the cancer survivors was accurate or helpful. In some cases, advice from family and friends delayed access to care by presenting doubt in a cancer diagnosis or advising them against medical treatment for cancer based on the belief that the drugs and treatment given at the hospital would be harmful. There was advice rooted in misinformation, such as to avoid sex because the cancer could be spread to the patient’s spouse, and advice to pursue alternative medicine. These instances highlight the importance of high-quality informational support, and the potential for what is intended as informational support to spread misinformation. This is an issue that has been examined in studies focusing on the quality of informational support provided online, especially through online health communities, where there is no gatekeeping of who can make a post or the content posted (Petrič et al., 2023). There is a prevalence of health misinformation on social media, including about cancer treatments, which cancer patients in Malawi are likely also accessing. In one study among US adults with cancer, almost 1 in 4 received advice, mostly from family and friends, about alternative ways to treat cancer, and more than half were exposed to cancer treatment misinformation on social media (Lazard et al., 2023).

Susceptibility to misinformation and advice from family and friends suggesting alternative medicine emerged among many of the patients we interviewed in Malawi, underscoring the importance for high quality informational support. One way to facilitate this is the involvement of healthcare providers in the community-based education methods discussed previously. Some level of gatekeeping or moderation by a healthcare provider in an online support group, for example, could be helpful in combatting advice rooted in misinformation.

Emotional and informational support often co-occurred for patients linking to and initiating cancer care. Especially considering community myths and beliefs about cancer as a death sentence, strong encouragement was needed from friends and family to take the leap and commit to undergoing cancer treatment. Encouragement to start treatment was often rooted in a belief in the medical system and effectiveness of cancer drugs, sometimes based on personal knowledge of people who survived cancer. The need for emotional support in the form of encouragement to continue treatment was also highly present in the retention and completion stage. An effective intervention to address the need for encouragement through emotional and informational support, especially at the stage of initiating care, could be the use of support groups connecting newly diagnosed cancer patients to cancer survivors.

Multiple survivors expressed in their interviews a willingness and desire to help newly diagnosed patients by providing this support. This aligns with the idea of reciprocity, which suggests that patients not only benefit from receiving social support, but also by providing it to others themselves (Robinson & and Tian, 2009). Additionally, in accordance with the view that the most effective social support may come from “similar others,” cancer survivors would be well-positioned to provide informational and emotional support related to treatment to newly diagnosed patients, as individuals who have experienced the same challenges (Thoits, 1995).

Previous studies have shown social support groups can reduce psychological distress for patients experiencing cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, heart disease, and others (Taylor, 2012). These are especially beneficial for health conditions that are stigmatizing, such as HIV, alcoholism, and epilepsy. Given that cancer can be highly stigmatized in LMICs where diagnosis and treatment services are not widely available (Bamodu & Chung, 2024; Watt et al., 2023), these interventions may be salient for cancer in LMICs. In their review, Helgeson and Cohen (1996) examined studies on interventions, including those with an educational component and discussion component, aiming to provide informational and emotional support. Comparisons between the two indicated that educational support groups were more effective than discussion-based support groups, generating positive effects in a shorter period of time. Helgeson and Cohen provide multiple possible explanations. One explanation is that patients may prefer emotional support from existing network members, such as family and friends, rather than emotional support from other cancer patients, with whom the relationship might not be as intimate. A study by Poole (2001) observed the impacts of support groups for men with prostate cancer by comparing support group attendees and nonattenders. The study found that patients who were in support groups were more likely to report other cancer patients as a source of informational support compared to those who were not in support groups. Both attenders and non- attenders cited their spouses most often as their primary source of emotional and instrumental support. Patients who attended support groups did not report better coping or quality of life compared to non- attenders, likely because some patients who did not attend had access to social support from their own personal networks (Poole et al., 2001). The authors concluded that there may be certain men for whom support groups are a better fit than others, such as those who lack personal social support networks, and those who benefit from upward comparisons. This idea could be applied in the clinical setting in Malawi by screening for cancer patients reporting low levels of social support and targeting these groups with interventions focused on discussion and emotional support. Those who already have strong sources of emotional support from their personal networks may benefit more from support groups with other cancer patients and survivors focused on informational support. Support groups are also a good fit for LMICs due to being a relatively cost-effective intervention (Ochalek et al., 2023).

Instrumental support was significant at the retention and completion stage, explicitly referenced by almost every participant. Instrumental support has been much less commonly measured and emphasized in the literature in comparison to emotional and informational support, but the literature is clear that structural barriers such as transportation and finances create significant barriers to cancer care in LMICs (Bamodu & Chung, 2024; Brand et al., 2019). In the cases where instrumental support has been measured, its importance has been limited to patients with poor prognosis and worse functioning (Courtens et al., 1996; Helgeson & Cohen, 1996). Instrumental support has been conceptualized as an important resource for a successful transition from the hospital to home care in the wake of hospitalization, particularly for elderly adults (Schultz et al., 2022). There are well- documented side effects of cancer treatment, including nausea, vomiting, and fatigue, which would require more extensive instrumental support (Pedersen et al., 2013). Another reason instrumental support may have emerged more prominently in Malawi is the low-resource setting, which creates a need for certain tangible aid such as transportation or a place to stay while receiving treatment in hospitals located at far distances from patients’ homes. This is mirrored in certain populations in the US of lower socioeconomic status. For example, a study on Latina women with breast cancer showed that participants with lower levels of instrumental support were more likely to drop out of treatment prematurely, due to issues such as inability to pay for treatment and long transportation distances (Galván et al., 2009). Instrumental support related to food was particularly prominent, co-occuring with informational support in the form of nutritional advice, such as which foods to eat to boost immunity and avoid nausea. Patients in Malawi may be particularly concerned with nutrition due to the abundance of malnutrition and under-nutrition. This has been studied particularly among children and adolescents with cancer. A study on malnutrition among children with cancer in Malawi revealed that more than half of the children are severely malnourished and over 95% have some degree of malnutrition (Israëls et al., 2008). Similar findings were present in other LMICs, including India and Guatemala (Barr & Antillon-Klussmann, 2022). Malnutrition contributes to early abandonment of therapy, treatment-related toxicities, poor clinical outcomes, and low survival rates (Barr & Antillon-Klussmann, 2022). Considering the importance of nutrition in this context, it could be helpful to incorporate advice on nutrition into informational support provided by the medical team, as well as instrumental support to provide nutritious food that minimizes unpleasant side effects to those who are otherwise unable to obtain it.

Emotional support emerged as a major need during the stage of retention and completion. The importance of emotional support for cancer patients has been the most heavily emphasized in literature (Hegelson & Cohen, 1996). One study examined the effects of participation in a computer-mediated emotional support group among breast cancer patients, finding that participation was associated with perceived bonding, which was associated with positive coping strategies (Namkoong et al., 2013).

There were multiple ways emotional support manifested at this stage. It emerged similarly to the stage of initiation of care in many cases, with family and friends providing encouragement for patients to continue treatment. In other cases, it co-occurred with instrumental support to promote treatment adherence. The connection between social support and treatment compliance was demonstrated in one study among patients with cardiovascular disease, showing that patients with higher social support also had greater adherence to appointments (Wenn et al., 2022). Emotional support also appeared in the form of providing companionship and making the patients feel loved and cared for. The source of emotional support was most often caregivers who were immediate family members such as the patient’s spouse, parents, or siblings. The role of support from family members in alleviating symptoms of depression in cancer patients has been documented in other studies (Hann et al., 2002). The presence of emotional support from these sources suggests that patients’ existing social support networks through their immediate families can, in many cases, be tapped into to provide them with needed support. Asking patients about their social support network and identifying individuals to fulfill certain needs can ensure needs are met effectively (Krishnasamy, 1996). As mentioned previously, not all cancer patients may need a formal support group to get emotional support. In these cases where they already have a strong social network, members of this network can be looped into care and given knowledge and tools to strengthen the support they are already providing.

The results did not demonstrate significant differences in social support needs between men and women across the cancer care continuum. One possible explanation for this is that gender differences might disappear after controlling for social roles, and in this case both men and women held the social role of a cancer patient (Matud et al., 2003). However, men more frequently cited their wife or partner as the person providing emotional and instrumental support, compared to less women who mentioned their husband. Past studies would support this finding. For example, although levels of confiding in others were the same between male and female cancer patients in one study, men were more likely to limit confiding to one person, usually their partner, while women were more likely to confide in a larger network of family and friends (Harrison et al., 1995). In a study observing differences in depression symptoms among cancer patients by age and gender, having a larger social support network was associated with less depression for women but was unrelated for men, echoing these findings (Hann et al., 2002). This is not to say that men do not need social support, as more social support was associated with less depression for both groups. Additionally, previous literature has established that the burden of social support typically falls on women, who are more likely than men to take on informal caregiving roles, as caregiving falls into expected gender norms (Parks & Pilisuk, 1991; Schrank et al., 2016). Female caregivers report higher levels of burden, stress, anxiety and fatigue compared with male caregivers, and spend more hours performing care duties and performing more intimate duties such as toilet tasks (Schrank et al., 2016). This highlights the need to not only support cancer patients but also the informal caregivers in their social support network, who may experience a large burden from their caretaking roles. Past studies have demonstrated that caretakers of patients with cancer can experience negative effects to their mental health and quality of life, and that these effects are interdependent with the patients’ mental health and quality of life (Grov et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2015).

This study has several limitations that must be considered. First, the study is limited in that it draws from a sample of survivors, meaning it does not capture perspectives from people who were unsuccessful in completing treatment, which would be helpful in determining if social support was a significant factor in treatment adherence and completion. A second limitation is that only informal sources of social support, including friends, family, and others in the community, were considered. Formal sources of social support, most notably healthcare providers including oncologists and nurses, were not considered in our analysis as social support. Although their contribution emerged in some patient narratives which referenced conversations with nurses or medical providers as a source of informational and emotional support, these references were excluded from analysis. Other studies have considered these formal sources of support, such as one study which explored sex-based trends and found women with breast cancer preferred nurses as their source of informational support, while men with prostate cancer preferred their oncologist (Dubois & Loiselle, 2009). Another study explored the provision of informational and emotional support by medical providers for the caregivers of cancer patients in Finland, finding that relatives considered it important to receive informational support from healthcare providers but felt they received very little in relation to their needs (Eriksson & Lauri, 2000). Especially considering the issues with the quality of informational support provided by patients’ informal social support networks, connections to formal sources of support including healthcare providers may be even more important in this population. Third, the interview guide was not designed to specifically ask about social support. Although themes surrounding social support emerged organically in the survivors’ narratives, it is possible that asking more targeted questions around social support would have better informed the results. Fourth, the interviews were translated from Chichewa to English but were not back translated, which may have resulted in the loss of some nuance in the transcripts. Finally, the sample of survivors included only those with breast cancer and lymphoma, limiting the generalizability of this study, although some broader social support patterns are applicable regardless of cancer type.

In conclusion, social support is a valuable resource utilized by cancer patients across the stages of the cancer care continuum. This study provides insight into how informational, emotional, and instrumental social support facilitated the journey of cancer survivors in Malawi from diagnosis to initiation to completion of treatment. Interventions to address gaps in social support should be a top priority to promote successful adherence to cancer treatment. This may include community-level education to address informational support needs in the pathway to diagnosis; peer-support groups to address emotional and informational support needs at the initiation of care; and transportation and food vouchers to meet instrumental support needs at retention in care. Insights from the narratives of cancer survivors should be used to inform and implement interventions that fulfil unmet social support needs and promote cancer survival.

Bibliography

Agampodi, T. C., Agampodi, S. B., Glozier, N., & Siribaddana, S. (2015). Measurement of social capital in relation to health in low and middle income countries (LMIC): A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 128, 95–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.01.005

Ajith, K., Sarkar, S., Sethuramachandran, A., Manghat, S., & Surendran, G. (2023). Myths, beliefs, and attitude toward cancer among the family caregivers of cancer patients: A community- based, mixed-method study in rural Tamil Nadu. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 12(2), 282. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_193_22

Anandasabapathy, S., Asirwa, C., Grover, S., & Mungo, C. (2024). Cancer burden in low-income and middle-income countries. Nature Reviews Cancer, 24(3), 167–170. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-023-00659-2

Bamodu, O. A., & Chung, C.-C. (2024). Cancer Care Disparities: Overcoming Barriers to Cancer Control in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. JCO Global Oncology, 10, e2300439. https://doi.org/10.1200/GO.23.00439

Banning, M., & Hafeez, H. (2009). Perceptions of breast health practices in Pakistani Muslim women. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention: APJCP, 10(5), 841–847.

Barr, R. D., & Antillon-Klussmann, F. (2022). Cancer and nutrition among children and adolescents in low- and middle-income countries. Hematology (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 27(1), 987–993. https://doi.org/10.1080/16078454.2022.2115437

Beasley, J. M., Newcomb, P. A., Trentham-Dietz, A., Hampton, J. M., Ceballos, R. M., Titus-Ernstoff, L., Egan, K. M., & Holmes, M. D. (2010). Social networks and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 4(4), 372–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-010-0139-5

Berkman, L. F., Glass, T., Brissette, I., & Seeman, T. E. (2000). From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 51(6), 843–857. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4

Brand, N. R., Qu, L. G., Chao, A., & Ilbawi, A. M. (2019). Delays and Barriers to Cancer Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. The Oncologist, 24(12), e1371– e1380. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0057

Cai, T., Huang, Q., & Yuan, C. (2021). Emotional, informational and instrumental support needs in patients with breast cancer who have undergone surgery: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 11(8), e048515. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048515

Christiansen, K., Buswell, L., & Fadelu, T. (2023). A Systematic Review of Patient Education Strategies for Oncology Patients in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. The Oncologist, 28(1), 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/oncolo/oyac206

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

Courtens, A. M., Stevens, F. C., Crebolder, H. F., & Philipsen, H. (1996). Longitudinal study on quality of life and social support in cancer patients. Cancer Nursing, 19(3), 162–169. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002820-199606000-00002

Datta, N. R., Samiei, M., & Bodis, S. (2014). Radiation Therapy Infrastructure and Human Resources in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Present Status and Projections for 2020. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics, 89(3), 448–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.03.002

Drageset, J. (2021). Social Support. In G. Haugan & M. Eriksson (Eds.), Health Promotion in Health Care – Vital Theories and Research. Springer. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK585650/

Drageset, J., Eide, G. E., Dysvik, E., Furnes, B., & Hauge, S. (2015). Loneliness, loss, and social support among cognitively intact older people with cancer, living in nursing homes – a mixed-methods study. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 10, 1529–1536. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S88404

Dubois, S., & Loiselle, C. G. (2009). Cancer informational support and health care service use among individuals newly diagnosed: A mixed methods approach. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 15(2), 346–359. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01013.x

Eriksson, E., & Lauri, S. (2000). Informational and emotional support for cancer patients’ relatives. European Journal of Cancer Care, 9(1), 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365- 2354.2000.00183.x

Ezeome, E. R., & Anarado, A. N. (2007). Use of complementary and alternative medicine by cancer patients at the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Enugu, Nigeria. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 7, 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-7-28

Galván, N., Buki, L. P., & Garcés, D. M. (2009). Suddenly, a carriage appears: Social support needs of Latina breast cancer survivors. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 27(3), 361–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347330902979283

Gottlieb, B. H., & Bergen, A. E. (2010). Social support concepts and measures. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 69(5), 511–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.10.001

Grov, E. K., Dahl, A. A., Moum, T., & Fosså, S. D. (2005). Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in caregivers of patients with cancer in late palliative phase. Annals of Oncology, 16(7), 1185–1191. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdi210

Guest, G., M.MacQueen, K., & E.Namey, E. (2012). Applied Thematic Analysis. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483384436

Hann, D., Baker, F., Denniston, M., Gesme, D., Reding, D., Flynn, T., Kennedy, J., & Kieltyka, R. L. (2002). The influence of social support on depressive symptoms in cancer patients: Age and gender differences. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 52(5), 279–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00235-5

Harrison, J., Maguire, P., & Pitceathly, C. (1995). Confiding in crisis: Gender differences in pattern of confiding among cancer patients. Social Science & Medicine, 41(9), 1255–1260. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(94)00411-L

Helgeson, V. S., & Cohen, S. (1996). Social support and adjustment to cancer: Reconciling descriptive, correlational, and intervention research. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 15(2), 135–148. https://doi.org/10.1037//0278-6133.15.2.135

House, J. S., Umberson, D., & Landis, K. R. (1988). Structures and Processes of Social Support. Annual Review of Sociology, 14, 293–318.

Israëls, T., Chirambo, C., Caron, H. N., & Molyneux, E. M. (2008). Nutritional status at admission of children with cancer in Malawi. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 51(5), 626–628. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.21697

Kim, Y., van Ryn, M., Jensen, R. E., Griffin, J. M., Potosky, A., & Rowland, J. (2015). Effects of gender and depressive symptoms on quality of life among colorectal and lung cancer patients and their family caregivers. Psycho-Oncology, 24(1), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3580

Krishnasamy, M. (1996). Social support and the patient with cancer: A consideration of the literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 23(4), 757–762. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365- 2648.1996.tb00048.x

Kroenke, C. H., Kubzansky, L. D., Schernhammer, E. S., Holmes, M. D., & Kawachi, I. (2006). Social Networks, Social Support, and Survival After Breast Cancer Diagnosis. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 24(7), 1105–1111. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.04.2846

Kroenke, C. H., Quesenberry, C., Kwan, M. L., Sweeney, C., Castillo, A., & Caan, B. J. (2013). Social networks, social support, and burden in relationships, and mortality after breast cancer diagnosis in the Life After Breast Cancer Epidemiology (LACE) study. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 137(1), 261–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-012-2253-8

Lazard, A. J., Nicolla, S., Vereen, R. N., Pendleton, S., Charlot, M., Tan, H.-J., DiFranzo, D., Pulido, M., & Dasgupta, N. (2023). Exposure and Reactions to Cancer Treatment Misinformation and Advice: Survey Study. JMIR Cancer, 9(1), e43749. https://doi.org/10.2196/43749

Makwero, M. T. (2018). Delivery of primary health care in Malawi. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 10(1), 1799. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v10i1.1799

Manvelian, A., & Sbarra, D. A. (2020). Marital Status, Close Relationships, and All-Cause Mortality: Results From a 10-Year Study of Nationally Representative Older Adults. Psychosomatic Medicine, 82(4), 384–392. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000798

Matud, M. P., Ibáñez, I., Bethencourt, J. M., Marrero, R., & Carballeira, M. (2003). Structural gender differences in perceived social support. Personality and Individual Differences, 35(8), 1919–1929. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00041-2

Muñoz-Laboy, M., Severson, N., Perry, A., & Guilamo-Ramos, V. (2014). Differential Impact of Types of Social Support in the Mental Health of Formerly Incarcerated Latino Men. American Journal of Men’s Health, 8(3), 226–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988313508303

Namkoong, K., McLaughlin, B., Yoo, W., Hull, S. J., Shah, D. V., Kim, S. C., Moon, T. J., Johnson, C. N., Hawkins, R. P., McTavish, F. M., & Gustafson, D. H. (2013). The Effects of Expression: How Providing Emotional Support Online Improves Cancer Patients’ Coping Strategies. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Monographs, 2013(47), 169–174. https://doi.org/10.1093/jncimonographs/lgt033

Ochalek, J., Gibbs, N. K., Faria, R., Darlong, J., Govindasamy, K., Harden, M., Meka, A., Shrestha, D., Napit, I. B., Lilford, R. J., & Sculpher, M. (2023). Economic evaluation of self-help group interventions for health in LMICs: A scoping review. Health Policy and Planning, 38(9), 1033–1049. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czad060

Pace, L. E., Mpunga, T., Hategekimana, V., Dusengimana, J.-M. V., Habineza, H., Bigirimana, J. B., Mutumbira, C., Mpanumusingo, E., Ngiruwera, J. P., Tapela, N., Amoroso, C., Shulman, L. N., & Keating, N. L. (2015). Delays in Breast Cancer Presentation and Diagnosis at Two Rural Cancer Referral Centers in Rwanda. The Oncologist, 20(7), 780–788. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0493

Park, K., Hong, W. H., Kye, S. Y., Jung, E., Kim, M., & Park, H. G. (2011). Community-based intervention to promote breast cancer awareness and screening: The Korean experience. BMC Public Health, 11, 468. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-468

Parks, S. H., & Pilisuk, M. (1991). Caregiver burden: Gender and the psychological costs of caregiving. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 61(4), 501–509. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0079290

Pedersen, B., Koktved, D. P., & Nielsen, L. L. (2013). Living with side effects from cancer treatment—A challenge to target information. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 27(3), 715–723. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01085.x

Perry, B. L., & Pescosolido, B. A. (2012). Social Network Dynamics and Biographical Disruption: The Case of “First-Timers” with Mental Illness. American Journal of Sociology, 118(1), 134–175. https://doi.org/10.1086/666377

Petrič, G., Cugmas, M., Petrič, R., & Atanasova, S. (2023). The quality of informational social support in online health communities: A content analysis of cancer-related discussions. DIGITAL HEALTH, 9, 20552076231155681. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076231155681

Poole, G., Poon, C., Achille, M., White, K., Franz, N., Jittler, S., Watt, K., Cox, D. N., & Doll, R. (2001). Social support for patients with prostate cancer: The effects of support groups. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 19(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1300/J077v19n02_01

Portes, A. (1998). Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 24, 1–24.

Pramesh, C. S., Badwe, R. A., Bhoo-Pathy, N., Booth, C. M., Chinnaswamy, G., Dare, A. J., de Andrade, V. P., Hunter, D. J., Gopal, S., Gospodarowicz, M., Gunasekera, S., Ilbawi, A., Kapambwe, S., Kingham, P., Kutluk, T., Lamichhane, N., Mutebi, M., Orem, J., Parham, G., Weiderpass, E. (2022). Priorities for cancer research in low- and middle-income countries: A global perspective. Nature Medicine, 28(4), 649–657. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01738-x

Reblin, M., & Uchino, B. N. (2008). Social and Emotional Support and its Implication for Health. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 21(2), 201–205. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f3ad89

Robinson, J. D., & and Tian, Y. (2009). Cancer Patients and the Provision of Informational Social Support. Health Communication, 24(5), 381–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410230903023261

Schrank, B., Ebert-Vogel, A., Amering, M., Masel, E. K., Neubauer, M., Watzke, H., Zehetmayer, S., & Schur, S. (2016). Gender differences in caregiver burden and its determinants in family members of terminally ill cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology, 25(7), 808–814. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4005

Schultz, B. E., Corbett, C. F., & Hughes, R. G. (2022). Instrumental support: A conceptual analysis. Nursing Forum, 57(4), 665–670. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12704

Schwarzer, R., & Leppin, A. (1991). Social Support and Health: A Theoretical and Empirical Overview. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 8(1), 99–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407591081005

Story, W. T. (2013). Social capital and health in the least developed countries: A critical review of the literature and implications for a future research agenda. Global Public Health, 8(9), 983–999. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2013.842259

Sung, H., Ferlay, J., Siegel, R. L., Laversanne, M., Soerjomataram, I., Jemal, A., & Bray, F. (2021). Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 71(3), 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660

Taylor, S. E. (2012). Social Support: A Review. In H. S. Friedman (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Health Psychology (1st ed., pp. 190–214). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195342819.013.0009

Thoits, P. A. (1995). Stress, coping, and social support processes: Where are we? What next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53–79. https://doi.org/10.2307/2626957

Ward, Z. J., & Goldie, S. J. (2024). Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 estimates: Implications for health policy and research. The Lancet, 403(10440), 1958–1959. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00812-2

Watt, M. H., Suneja, G., Zimba, C., Westmoreland, K. D., Bula, A., Cutler, L., Khatri, A., Painschab, M. S., & Kimani, S. (2023). Cancer-Related Stigma in Malawi: Narratives of Cancer Survivors. JCO Global Oncology, 9, e2200307. https://doi.org/10.1200/GO.22.00307

Wenn, P., Meshoyrer, D., Barber, M., Ghaffar, A., Razka, M., Jose, S., Zeltser, R., & Makaryus, A. N. (2022). Perceived Social Support and its Effects on Treatment Compliance and Quality of Life in Cardiac Patients. Journal of Patient Experience, 9, 23743735221074170. https://doi.org/10.1177/23743735221074170

Wortman, C. B. (1984). Social Support and the Cancer Patient: Conceptual and Methodologic Issues. Cancer, 53(S10), 2339–2360. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.1984.53.s10.2339