College of Social and Behavioral Science

128 Specialty Courts: Resources, Outcomes & Success of Family Recovery Court

Annia Hungerford

Faculty Mentor: Rebecca Owen (Sociology, University of Utah)

ABSTRACT

The basis for this research is to understand how specialty courts operate differently from standardized courtroom procedures, by analyzing the resources, outcomes and success of Family Recovery Court based out of the 3rd District Juvenile Courthouse in Salt Lake City, Utah. Family Recovery Court is a rehabilitative program that offers an alternative holistic approach to parents recovering from addiction who want to reunify with their children. The outcomes and success of Family Recovery Court are based on principles that are not traditionally applied to standard juvenile court proceedings. The support offered to families in Family Recovery Court proceedings differs dramatically (Wittouck et al., 2013).

The outcomes of Family Recovery Court aren’t solely based on the individual’s participation, but the astounding team behind each successful family reunification. The model that specialty courts abide by, is restorative justice, which seeks to repair harm by providing an opportunity for those who harmed another to take responsibility while addressing their own needs in the aftermath. This ensures that all parties receive justice, with additional rehabilitation and treatment to establish healthy boundaries ensuring that the wrongdoing doesn’t continue to occur (Snell, 2015). These principles provide insight into the success and outcomes of Family Recovery Court.

Sociological and criminological theories support the assertion that Family Recovery Court offers an increased amount of assistance to parents in the community of Salt Lake City, who are struggling with addiction. Several criminal justice actors are appointed to this court specifically to give additional contributions (Lowenkamp et al., 2005). These criminal justice actors are not traditionally allotted to support parents in standard juvenile court hearings, which immediately sets Family Recovery Court apart. Emotional Support Animals, Peer Support Specialists, Recovery Liaisons, and Parent Advocates are a few of the many individuals appointed to lend their resources to families struggling with addiction. This research utilizes Family Ecological Systems Theory and Social Control Theory which both focus on the importance of environmental factors and social support. To complete this research, two methods of data collection were utilized including six- months of court observations and seven interviews were conducted. This research strives to understand how Salt Lake City’s 3rd District Family Recovery Court offers more resources and social support than the traditional court and child welfare system. Of particular interest is understanding further which specific forms of social support and/or treatment lead to the most successful outcomes for participants of Family Recovery Court.

Introduction

Walking into that tall white building with marble slab and granite stairs felt daunting even for me as an intern; so I could only imagine the angst someone might feel if they were there to fight for their family, and navigate the legal system, all while battling an addiction. At first, I felt weary of entering Family Recovery court, being that my experience in a courtroom had been limited. As an intern there was much to uncover about the law especially pertaining to families. Yet, as soon as I stepped into Family Recovery Court, that unsettling feeling dwindled and instantly I knew this was going to be a different experience. I could feel the warmth in the room radiate across each individual who shared their experiences being employed by Family Recovery Court and how much they loved the work they do.

Then, as we began our first hearing of the day, I felt the full effect of inspiration in this courtroom. Each participant spoke upon their struggles in battling addiction and the hardships they faced fighting to reunify with their families. Not only had this been a touching moment, but after each participant went before the judge, the room echoed with applause and cheerful words of encouragement. It was certainly unlike any courtroom I’ve experienced or even heard of, and it all seemed hard to believe with the amount of positivity and joy that beamed from their faces. Despite the positive aspects of Family Recovery Court, battling addiction is a serious hardship and has a profound impact on families facing these challenges. After thoroughly observing the complex components of Family Recovery Court, I decided to dive into the reality of what addiction recovery actually is for participants who find themselves in these legal precedents.

Family Recovery Court (FRC) is a specialty court, designed to support parents struggling with substance use disorders while working toward family reunification. By providing comprehensive services, judicial oversight, and a collaborative approach, FRC helps families navigate recovery and the legal system in a more compassionate and structured environment.

One participant, let’s call her Mabel, in particular had been an addict since the age of 14, and she had several children previously removed from her custody prior to engaging in Family Recovery Court. After several years, Mabel had a baby who was in jeopardy of being removed from her custody only a few weeks after giving birth. Mabel then decided to try Family Recovery Court, and after a few months in the program, she was on track to recovery, becoming a success story that absolutely transformed the lives of those around her. Through Utah Recovery Awareness Advocates (USARA), and the resources provided by FRC, Mabel not only achieved sobriety but also addressed the underlying trauma that had fueled her addiction. She attended parenting classes, rebuilt trust with her caseworkers, and slowly began repairing her relationships with her child. The structured and compassionate nature of Family Recovery Court allowed her to feel seen and supported, rather than punished for her addiction. Several months later and with full dedication, Mabel became a success story. She regained custody of her child and, more importantly, became a source of inspiration for others in the program.

Mabel’s determination and unwavering commitment to reunify with her child served as a beacon of hope for so many other participants, even those who worked in FRC. This inspired everyone to believe that change was possible, no matter what past struggles they may have faced, and it was a testament to the power of second chances.

This research paper will explore the impact of Family Recovery Court on parents struggling with substance use disorders, examining how this specialty court differs from traditional court, and how the supportive approach creates long-term recovery outcomes as well as family reunification. By analyzing this court’s structure, including peer mentorship programs like USARA, and the personal journeys of participants, this paper will highlight how Family Recovery Court humanizes the legal process and offers a path toward lasting change.

Literature Review

The Child Welfare System

In the past, the child welfare system was designed to permanently place children who were experiencing abuse or neglect of any kind into the foster care system based on their parent(s) or extended relatives being deemed unfit to care for them. These children were then removed from their home and placed in the custody of the state without reunification to their parent(s) (Berger & Slack, 2020). However, after several decades of the foster care system being the primary placement for children, the functionalities of this apparatus are no longer sustainable. Foster families are in high demand, causing a chain reaction to the entire system where children are staying in state-run facilities for extended periods of time. Studies have indicated that the best interest of a child is to have them reunited with their biological parents or a kinship placement if possible. Stability, emotional security, and economic support are necessary for the proper development of a child and the constant change of children shifting into different environments creates confusion. One issue has long been providing the entire family with support rather than solely the children, and aiding parents to get the help that they need as well (Freisthler et al., 2021).

To address these issues of the past, enhancing permanency within families has become the central focus of child welfare. Today, in the State of Utah, Salt Lake County Youth Services has a juvenile receiving center, where children are placed in the care of professionals, until the Division of Child and Family Services (DCFS) finds a placement for them. Salt Lake County Youth Services provides, “safety, shelter, and support to at- risk and under-served youth and families residing in Salt Lake County.” (Youth Services, 2024). Placement of a child depends on the status of their child welfare case, and if additional services are needed before the child is placed elsewhere. They could either go to a treatment facility to treat trauma or other mental health disorders, go to a foster family, a group home, or reside with extended family which is referred to as a kinship placement. These children only return to the custody of their parents if a judge orders reunification services, which is contingent upon their Social Worker finding that the parent is following their child and family plan. The mission statement for the Utah Division of Child and Family Services today is “to keep children safe from abuse and neglect through the strengthening of families” (DCFS, n.d.). This concept of strengthening families, rather than tearing them apart, has been the mission of recent decades.

Evolution Of Families

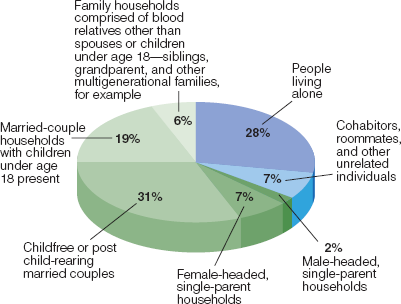

The way that families are defined today in society is drastically different from the perspectives several decades ago. These ideas have continued to evolve, providing the support for how the Criminal Justice System handles child welfare cases today. Family functions and structures have changed over several decades. The philosophy of the nuclear family structure which was prominent in the 1950’s, emphasized the husband as the breadwinner, the wife as the homemaker, and the children living with both of their biological parents. Today, only 5% of Americans resemble the nuclear family (Vespa et al., 2013) and the vast majority are considered under the umbrella term, “post-modern families” that consist of single parent households, stepfamilies, two earner couples, stay at home fathers, and LGTBQ+ couples.

Modern family dynamics take many forms, although the Census Bureau only labels households as “family”, if they align with that traditional nuclear family structure of a husband and wife living with their biological children. As indicated in this figure only 6% of households are defined as ‘family’ households, even though there are other households which include married couples with children, married couples without children, and female or male headed single-parent households. These American households are not considered families by the Census Bureau, but are defined as one or more persons who occupy a dwelling unit or domicile. This can include biological relatives or non-biological members living together in a single household. However, family households are indicated only as persons related by blood, marriage, or adoption. This figure displays the nonfamily households in shades of blue and the family households in shades of green, with the color differences emphasizing the Census Bureau’s classification system. Nonfamily households, shown in blue, represent living arrangements that do not meet the criteria of a traditional family, whereas family households, shown in green, highlight the structures officially recognized as families under the Census Bureau’s definition. (Lamanna et al., 2021).

Figure 1. Household and Family Structure in the United States, 2018.

Nevertheless, there continues to be more social acknowledgement that there is no one definition of family, and that family is an adaptable institution, which could include extended relatives or non-biological family members related through marital unions. Our societal perceptions of family are becoming more flexible, due to getting rid of the rigid 1950s conceptualization that focused on a nuclear family model with a breadwinning father, homemaking mother, and biological children, which is no longer suitable in modern day reality. This shows a deeper cultural transition toward inclusivity and recognizing diverse family forms, by acknowledging that emotional bonds, support systems, and shared experiences can define a family just as strongly as biology or traditional roles.

Families & The System

The United States Supreme Court has also expanded their definition of family over time, by granting custody of children to single mothers, single fathers, and stepparents, who would have previously been denied custody based on assumptions that they would not be able to provide sufficient care. In Troxel v. Granville, the Supreme Court ruled on issues of parental rights, highlighting the nature of family structures and the legal recognition of different family dynamics, including single parents. This case illustrates how courts have increasingly acknowledged the legitimacy of custody arrangements involving single mothers and fathers, countering previous assumptions about their ability to provide adequate care. (Troxel v. Granville, 2000).

Furthermore, according to Utah Juvenile Code Section 80-3-102, an immediate family member is defined as “a spouse, child, parent, sibling or grandparent”, whereas an extended relative is defined as “an adult who is the child’s brother-in-law, sister-in-law, stepparent, stepsibling, first cousin, great grandparent, aunt, great aunt, uncle or great uncle.” (Utah Juvenile Code, 2022). However, this represents a shift in acknowledging the makeup of various types of families, because back in the 1980’s the definition of relative did not include stepparents. In order for a judge to approve an adoption for a stepparent, they would have to file a petition to the court to terminate the rights of the noncustodial biological parent. This essentially meant terminating the rights of the parent who did not receive custody of the child in a divorce, because our legal system did not generally recognize two legal mothers or two legal fathers (Bartlett, 2001). Therefore, in order for a stepparent to gain rights, the biological parent must lose them, but this case concluded the dispute of judges choosing between biological and nonbiological family when considering the best interest of a child. There are several factors that are weighed when examining the best interest of a child, and situationally, every child’s needs are unique to their circumstances.

When examining how families are brought into the Criminal Justice or Child Welfare Systems, they interact separately but are reliant on each other for fundamental decision making on permanency between families. In child welfare, permanency is defined as a “permanent, stable living situation, ideally one in which family connections are preserved.” (Child Welfare, n.d.).

There are four broad categories of scenarios in which families involved in these systems are reviewed for permanency and reunification. These include, but are not limited to (1) instances of parent arrest and child maltreatment that coincide; (2) consideration of parents’ criminal histories in the decision to remove children from the care of their parent(s); (3) consideration of relatives’ criminal histories in decisions to place children in foster care; and (4) instances in which Child Protective Services agencies become involved with children whose parents are incarcerated because of risks to children’s current safety or inadequate resources (Phillips et al., 2010). Within these four categories, there may also be variations depending on each family’s unique circumstances. Preventative measures are often set in place by Child Protective Services to ensure there are opportunities for families to correct any issues before they become matters of the court. Families are handled situationally and circumstantially based upon the best interest of the child(ren). Additionally, a parent, relative or guardian may have multiple criminal, domestic, or civil cases occurring simultaneously alongside their child welfare investigation. This causes an overlap of how families are handled in the courtroom with different factors being considered on both ends. Child welfare focuses on the best interest of the child by determining permanency of the child(ren) depending on the circumstances of the family situation. Whereas, criminal court procedures focus on the behavior of the parent first, then consider whether that affects the best interest of the child and if the parent is suitable to be with their child(ren). Laws can vary by state, but certain offenses may constitute a termination of parental rights all together if the crime is severe enough.

Considering how families interact with the legal system, especially in the child welfare and criminal proceedings, it’s important to note that traditional court models often lack the necessary components to address these complex and intertwined issues. Families facing systemic challenges and limitations need to have these challenges viewed under a different lens, where more rehabilitative approaches are being used. One of the more established alternative court systems has been drug courts, and the emergence of these holistic programs has focused on the intersection of substance abuse, criminal behavior and personal stability.

History Of Drug Courts

The history of drug courts in the United States dates back to the late 1980s, emerging as a response to the growing concerns about drug-related crime and the limitations of traditional criminal justice approaches. Drug courts differ significantly from traditional criminal courts in their approach to addressing substance use and related offenses through restorative justice. By definition, this new concept of restorative justice encompasses a process that aims to repair harm by bringing together those affected by a crime to address their needs and create solutions.

While traditional courts primarily focus on punishment, drug courts emphasize rehabilitation and treatment for nonviolent drug offenders (Huddleston & Marlowe, 2011). They operate with a specialized team that includes judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys, and treatment providers, promoting collaboration to ensure comprehensive support for participants (Marlowe & Hardin, 2005). The structure of drug courts includes regular judicial oversight, frequent drug testing, and the use of incentives and sanctions to motivate individuals to comply with their treatment programs (National Institute of Justice, 2016). These incentives may include a medallion of sobriety based on the length of time they have been consistent in their treatment plans, as well as special recognition from the judge in drug court. The sanctions on the other hand can extend as far as serving time in jail if a participant is not staying in their treatment program and needs to be under intensive supervision in order to detox. This is designed to facilitate a collaborative and supportive environment for participants, which differs drastically from the adversarial nature of traditional criminal courts. In drug courts, a single judge typically oversees cases, which offers a more personal connection to participants and provides active engagement in their recovery process (Huddleston & Marlowe, 2011). This model also allows for regular court hearings where progress is monitored, and immediate feedback is provided through incentives for completing certain milestones in their treatment programs, or sanctions for non-compliance (National Institute of Justice, 2016). This unique structure of drug courts not only prioritizes accountability but also enhances the likelihood of successful outcomes for participants by addressing their holistic needs (ONDCP, 2015).

Additionally, mental health is also a driving factor in the invention of drug courts, due to a shift in public perception towards substance abuse as a mental health disorder and a complex health issue, rather than solely focusing on crime (Marlowe, 2003).

Substance Use Disorder often referred to as SUD, is a treatable mental health disorder that affects a person’s brain and behavior, ultimately leading to their inability to control their use of substances such as illegal drugs, alcohol, or medications. Individuals with SUD may also have co-occurring mental health disorders such as anxiety, depression, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), bipolar disorder, personality disorders, and schizophrenia, etc. (National Institute of Mental Health, n.d.). This conceptual change prompted a more rehabilitative approach, integrating treatment within the judicial process. The first drug court was established in Miami, Florida, in 1989, aiming to provide an alternative to incarceration for nonviolent drug offenders (Huddleston & Marlowe, 2011). This innovative model for drug courts sought to address the underlying substance use issues while still holding offenders accountable through judicial oversight.

Research indicates that drug courts can significantly reduce recidivism and substance use, increase employment, improve education and provide stable housing for individuals who participate, compared to traditional criminal court methods. A meta- analysis by (Mitchell et al., 2012) found that participants in drug courts were less likely to reoffend and had better treatment outcomes than those who were in conventional court settings. This effectiveness has led to increased support and funding for drug court programs, often supported by federal initiatives such as the Drug Court Program Office, which was established in 1995 to enhance the development and implementation of drug courts nationwide (Lurigio, 2008).

However, drug courts continue to face challenges including issues related to access and treatment quality across individuals within marginalized communities. Critics argue that these courts can perpetuate inequalities, such as disparities between socio- economic status, race and gender as participants may be subject to coercive conditions and may not receive adequate treatment (Belenko, 2001). Ongoing research aims to address these disparities and improve the overall effectiveness of drug courts. This includes implementing training for judges and court staff on cultural competency, ensuring equitable access to resources, and developing tailored treatment programs that address the unique needs of each participant. Ongoing evaluation of these initiatives can help track progress and accountability, ultimately leading to a more just and effective drug court system that serves all individuals fairly (Dannerbeck et al., 2006).

A critical issue has been the lack of comprehensive support for families dealing with both legal and social challenges. Child welfare systems often focus solely on the children’s needs, while drug courts emphasize rehabilitation for offenders, sometimes overlooking the family dynamics involved. In the past, when parents faced substance abuse issues, child welfare systems often removed children from their homes without considering the potential for recovery and reunification. This led to long-term separations that were not in the best interest of the child. The child welfare and drug courts systems have worked independently, but the integration of these two systems has led to the invention of Family Recovery Court, which aims to bridge this gap by recognizing that addressing a parent’s substance use is crucial for family stability. These courts offer a supportive environment where parents can receive treatment while maintaining connections with their children (CCFF, 2021).

Family Recovery Court

The evolution of families in society, the legal definition of who is considered family being changed in the criminal justice system, and the child welfare system aiming to strengthen families rather than separate them all led to the development of Family Recovery Court. Family Recovery Court integrates child welfare and criminal proceedings through drug courts in a collaborative approach to not only address the root causes of substance abuse, but also facilitate family reunification through tailored recovery plans that include both parental support and child welfare considerations. By offering services such as counseling, parenting classes, and access to social services alongside substance abuse treatment, these courts help parents rebuild their lives and relationships. This comprehensive support system addresses the emotional, economic, and social needs of families, fostering a stable environment conducive to recovery and child well-being (NCSC, 2018).

Family recovery courts are generally structured similarly to criminal courts. Walking into a Family Recovery courtroom hearing, the adversarial process remains the same, where a judge is presiding, and a Defense Attorney and Prosecutor are present. However, there are additional criminal justice actors such as Licensed Clinical Social Worker and a Guardian Ad Litem who speaks on behalf of the child(ren), which differs from a traditional criminal courtroom. All of these individuals provide support to the parents and their children who are involved in Family Recovery Court. They offer their knowledge of how each individual is progressing throughout recovery. The structure acknowledges that enhancing permanency in families relies on targeting the root of the issue, which in these cases is substance abuse disorders. These issues have to be dealt with first, thus creating an alternative strategy to bring families back together. The best interest of families is to strengthen the entire unit and focus on rehabilitation for each member (Moreno & Curti, 2012).

Unlike traditional courts that focus solely on legal consequences, Family Recovery Courts take a more holistic approach by addressing systemic barriers that contribute to inconsistency in maintaining sobriety and making long lasting change. This includes providing resources for education, employment opportunities, learning how to manage finances, and access to mental health services. Additionally, the court works to address issues such as domestic violence and housing, by recognizing that long-term family reunification depends on stability beyond just sobriety. By integrating this support system into Family Recovery Court, it not only helps parents recover but also equips them with the tools necessary to rebuild their lives and create a healthier environment for their children. (J.Quezada, personal communication, May 13, 2024)

Family Recovery Court combines principles from both the child welfare and drug court systems, which can lead to better outcomes for families. By addressing substance use issues and providing holistic support, these courts prioritize the well-being of children while empowering parents to overcome their challenges. This collaborative model for restorative justice not only facilitates reunification but also promotes long-term family stability and recovery.

Salt Lake City’s Family Recovery Court

Families are usually referred to Salt Lake City’s Family Recovery Court by their DCFS caseworker, through current treatment programs they are attending, or by word of mouth. Upon inquiry, each potential participant is given a handbook which thoroughly discusses the processes and structure of Salt Lake City’s 3rd District Family Recovery Court.

The mission of Salt Lake City’s 3rd District Family Recovery Court is to: Treat substance use addiction through an intense and concentrated program to preserve families and protect children. This is achieved through court-basedcollaboration and an integrated service delivery system for the parents of children who have come to the attention of the court on matters of abuse and neglect. A drug court team, including the judge, guardian ad litem, assistant attorney general, parent defense counsel, DCFS drug court specialist, clinical coordinator, program administrator, and drug court coordinators, collaborate to support the participants, monitor compliance at treatment, and court ordered requirements (Family Recovery Court, 2024).

In Salt Lake City’s Family Recovery court there is a judge presiding, a defense attorney for each parent, a DCFS case manager that is assigned to all of the parents of that courtroom, a prosecuting attorney is always an assistant attorney general who works in collaboration with the DCFS case manager, and a Guardian Ad Litem who speaks on behalf of the child(ren). Furthermore, there are Utah Support Advocates for Recovery Awareness (USARA) who act as peer coaches for the parents and a Parent Advocate that aids the parents in navigating and understanding the legal system.

Additionally, Treatment Coordinators from recovery programs such as House of Hope oversee each patient’s progress in treatment, ensuring that they comply with program requirements and receive the necessary resources for recovery. Licensed Clinical Social Workers (LCSW’s) and Clinical Coordinators provide therapeutic support, by conducting assessments, monitoring mental health needs, and coordinating care between treatment providers. As part of the program, parents are also required to find and work with a personal therapist to address their individual needs beyond the structured support of Family Recovery Court. Emotional support animals from Intermountain Therapy Dogs with their caretakers also provide support to the families in the courtroom. All of these individuals aim to provide moral support and input of their recovery journey aside from legal requirements. Having individuals in the courtroom who have gone through the recovery process, such as peer support coaches and treatment coordinators, who can speak on behalf of a participant’s progress, heavily impacts the decisions a judge makes in each court hearing. Having a variety of perspectives allows for a more nuanced approach to recovery, especially when everyone present understands that it takes a village to help a family battling addiction.

Ultimately, the primary goal is to provide timely permanency for children in a safe and drug-free environment. Although this program is meant to aid families, there is a certain level of dedication and commitment that a participant must make before enrolling. Before enrolling in Family Recovery Court, participants are given a handbook in which they must acknowledge a series of potential consequences which state the specific requirements of being in the program (3rd District Juvenile Court, 2024). They must agree that they understand that a missed drug/alcohol test will be considered a positive test result. Furthermore, they must also agree that a positive result, a diluted sample, a missed test, or intentionally violating a court order can result in a contempt of court charge. If the court finds them in contempt, the court will order a sanction, which can include but is not limited to, a written assignment, community service hours, or possible jail time. Individuals who have been referred to FRC are encouraged to observe the program at least twice before deciding to enroll. Participants are given a list of potential incentives and sanctions as well for successful or unsuccessful drug court participation, see figures 2 and 3.

Although a list is provided, it is not all encompassing and may vary depending on the judge presiding. This allows for judges to be flexible with how they decide to run their Family Recovery Court programs and positive behaviors can be highlighted in figure 2 (Utah State Courts, n.d.).

Figure 2. Family Recovery Court List of Potential Incentives & Positive Behavior

|

Positive Behavior Examples |

Incentive Examples |

|

Negative Drug Tests Achievements in Sobriety Successful Engagement in Treatment Successful Completion of Level of Care Drug Court Phase Advancement Completion of Specific Court Orders Demonstrating “Above & Beyond” Behavior Dealing With High-Risk Circumstances Without Relapse |

Court team Recognition and Praise Sobriety Medallions Phase Advancement Certificate of Phase Advancement Fewer Court Appearances Medallions and Wrist Bands Gift Card (Amount May Be Increased based on behavior between $5-$15) |

|

Graduating Family Recovery Court Incentives |

|

|

Certificate of Graduation Gift Bag Medallion $50 Gift Card Court Team Recognition and Praise |

|

Some of the most common sanctions are listed in figure 3. However, judges can use other sanctions based on their discretion (Utah State Courts, n.d.).

Figure 3. Family Recovery Court List of Potential Sanctions & Possible Violations

|

Possible Violations |

Possible Sanctions |

|

Drug Tests That Are: Positive Missed Tampered During Treatment: Failure to Attend Failure to Engage Leaving Treatment Discharged from Treatment Failure to Attend Drug Court Hearing Association With Known Drug Users Violation of Other Specific Orders |

Ordered to a Detox Program Write an Impact Statement Complete Workbook Write Essays Specific to the Individual Re-Assessment for Higher Level of Care Increase Frequency of Judicial Review Increase Time in Family Recovery Court Letter of Apology Admonishment Time Management Exercise Warrant Jail Sanctions May Increase for Serious Repeat Violations Unsuccessful Discharge from Family Recovery Court |

The most important aspect of Family Recovery Court which is duly noted in the participant handbook (Utah State Courts, n.d.), are the phases of the program. The FRC has four phases to assist in guiding a participant into recovery and throughout the entire experience. Each phase is designed to facilitate a natural progression from intake all the way through to graduation, with a total time commitment of no less than nine months, and generally twelve months in total from enrollment to graduation. The participant must complete an application or assignment in order to advance through to the next phase. The phases monitor the progression of treatment, set standards for advancement throughout the program, and assist in timeline management issues as they relate to permanency. The Family Recovery Court team uses the term “phasing up” when a participant is getting ready to move onto the next phase in the program.

Phase one is about establishing the participants with treatment and support options, phase two focuses on having the participants increase stability for themselves, phase three encompasses embracing their new life, and lastly, phase four centers around the participants maintaining what they’ve accomplished in treatment and their journey to recovery. The participant’s engagement in treatment and progress throughout the program is viewed relative to the phase timelines and structure of their child welfare case. While there are minimum participation times in Family Recovery Court that are established as part of graduation requirements, there are no maximum time limits on participation in the program. However, Family Recovery Court such as any other treatment program is a finite resource. Therefore, if an individual is not progressing throughout the four phases in a timely manner, they may be considered for an unsuccessful discharge from the program. The average length of time in the Family Recovery Court program is twelve months, unless an extension is granted through 18 months.

Phase one (Utah State Courts, n.d.) consists of participants getting into their treatment programs and completing required elements of sobriety such as connecting with their designated DCFS case manager. Each participant must also submit an application and assignment two days prior to court to be considered for advancement. The application to advance from phase one to phase two includes the following requirements:

-

-

-

No positive, missed or dilute urine analysis tests for a minimum of 30 days.

-

No unexcused absences at FRC for a minimum of 30 days.

-

-

-

-

-

Enrolled and currently attending treatment with an approved provider.

-

Working towards increasing the time that parents spend with their children and reporting on their visitation progress.

-

List their personal sobriety date for documentation.

-

Include a copy of their Child and Family Plan through DCFS.

-

-

-

-

-

Discussed their housing situation with the FRC Team.

-

State what they learned from a sanction they received during this phase in Family Recovery Court (if applicable).

-

-

Participants are also required to complete an assignment to advance that is geared toward improvements to their recovery that could be made going forward. For this assignment, they are encouraged to answer how their connection and communication can be improved upon and built with FRC as well as DCFS. They are then asked to list their three most important treatment goals from their treatment plan and talk about what boundaries they have set for existing and new relationships. Participants must then reflect on what they have learned so far about how they communicate and what they hope to improve on. They are also asked to answer how they are working to build their relationships with their children, peers and family as well as what recovery means to them. This allows for the participants to give their personal input on why they believe they should advance in the program and how they are going to execute that.

Phase two (Utah State Courts, n.d.) focuses on participants building their new life, because they are in a space where sobriety has been established and they are ready to begin recovering in other areas of their life. This phase primarily works towards establishing a social support network, getting connected with mental health resources, and resolving any remaining charges. The application to advance from phase two to three is similar, and includes the following requirements:

-

-

-

No positive, missed or dilute urine analysis tests for a minimum of 60 days.

-

No unexcused absences at FRC for a minimum of 60 days.

-

-

-

-

-

Their personal therapist needs to report on the progress of the client meeting treatment requirements.

-

All court ordered assessments (such as Domestic Violence or psychological) need to be completed or scheduled.

-

All warrants need to be resolved, and any pending charges working towards resolution.

-

They must be engaging in prosocial activities with either a mentor, sponsor, or peer support coach; and know who their main sober support person is, as well as with which organization they are affiliated.

-

Demonstrate progress with their three most important treatment goals they listed in phase one.

-

Indicate what they learned from a sanction they received during this phase in FRC (if applicable).

-

List their support such as a peer support coach, sponsor, mentor, family, friends, transportation or food assistance; and explain how these resources have supported them throughout the recovery process.

-

-

The assignment for phase two focuses on how they are going to maintain the progress they’ve already made. For instance, the first question is “How will I effectively use my sponsor or peer support coach to help maintain my recovery?” The idea is for participants to reflect on how they’ve gotten to where they are currently, so they do not lose the skills they’ve learned along the way. Another question the participants are asked is “What would a close friend/family member notice about me if I were heading toward using substances? Am I willing to share with my friends and family what they would notice? Have I had this conversation with them?”. This encourages participants to look past themselves and acknowledge their substance abuse as a disorder that can be treated.

Phase three (Utah State Courts, n.d.) is about having the participants truly embrace their new life and let go of their past through reconciliation and understanding that their prior decisions have unfortunately led them down a dark path. However, this lays the foundation for a newfound perspective within many participants for why it’s so important to maintain the progress they’ve made in recovery and continue making strides by making progress towards their new life. This phase often includes deeper self- reflection, by strengthening healthy coping mechanisms, and engaging more actively in their support networks. Participants may start mentoring others in earlier phases, but overall this phase focuses on reinforcing their own growth. The quote used on the application from the participant handbook is, “To embark on the journey towards your goals and dreams requires bravery. To remain on that path requires courage. The bridge that merges the two is commitment.” (Utah State Courts, n.d.). For this phase, the application to advance is similar to the previous two phases, and includes the following requirements:

-

-

-

No positive, missed or dilute urine analysis tests for a minimum of 90 days.

-

No unexcused absences at FRC for a minimum of 90 days.

-

Their personal therapist needs to report on the progress of the client meeting treatment requirements.

-

Be engaging in prosocial activities.

-

Need to meet with a mentor, sponsor or peer support coach at least once a week.

-

-

-

-

-

Need to have an employment or education plan.

-

Include their progress with their three most important treatment goals.

-

What they learned from a sanction they received during this phase in FRC (if applicable).

-

Give an example of how they used a mentor, sponsor or peer support coach.

-

-

-

-

-

Explain how they created and are holding boundaries with people who are unhealthy for their recovery.

-

Describe how they are seeking out people who are healthy and supportive of their recovery.

-

What they have learned in treatment that they are applying in their time spent with their children.

-

Describe their current housing situation and what their long-term housing plan is.

-

-

Participants must also complete an assignment that requires them to meet with the Family Recovery Court coordinator and identify the most significant areas of growth in their recovery journey. During this meeting, they will discuss key aspects of their progress and determine which areas they should focus on more intensely. From there, participants will choose five or more of the most important elements they have focused on while developing their recovery maintenance plan in treatment. Participants then present their progress in court, and demonstrate their commitment to making these changes in order to show they are ready to advance in the program. The areas they can choose from are, triggers and using behaviors, regulating emotions, relationships and friendships, communication, battling boredom, health, employment, housing, addressing legal issues, progress with DCFS case, financial and future goals. This assignment highlights key efforts in their recovery maintenance.

Phase four (Utah State Courts, n.d.) highlights all of the continuous progress throughout the participants’ time spent in Family Recovery Court and what they’ve accomplished in treatment as well as their journey to recovery. Phase four is essentially the end of the program for participants and a graduation application is required in order to be successfully discharged from Family Recovery Court. The graduation application checklist is similar to that of the previous three phases checklist requirements, and includes:

-

-

-

No positive, missed or dilute urine analysis tests for a minimum of 3 months.

-

No unexcused absences at FRC for a minimum of 3 months.

-

Engaging in prosocial activities.

-

-

-

-

-

Meeting with a mentor, sponsor or peer support coach at least once a week.

-

-

-

-

-

Graduated from treatment, or in good standing with their treatment provider.

-

Have no outstanding warrants, and are in compliance with all outstanding court orders.

-

Achieved, as determined to be appropriate, a restoration of custody, or a trial home placement of their children.

-

Have an employment and an education plan.

-

-

-

-

-

Discussed their housing situation and plans with the FRC team.

-

Include three things they would like to accomplish within five years after their child welfare case closes.

-

Indicate what they learned from a sanction they received during this phase in Family Recovery Court (if applicable)

-

Discuss their long-term recovery management plan for after they have left the program.

-

Explain who their mentor, sponsor or peer support coach is and how they help support their recovery.

-

Describe who their additional community supports are and how they have used them in a time of need.

-

Reflect on what reunification has meant to them personally.

-

Describe how they are going to ask for help once they are no longer involved with FRC and DCFS.

-

-

Although there isn’t an assignment for this phase, participants still need to apply for graduation. Included in the application are two optional questions. The first one asks them to tell the court about something that inspired them during their time in Family Recovery Court. Then, the second one asks what they would like to see improved, added or changed in Family Recovery Court. These questions are used in a rating survey for the Family Recovery Court team to assess the quality of the program and future development.

Family Recovery Court Proceedings

Family Recovery Court ensures that participants are held accountable while also being recognized for their efforts to become sober and develop the skills to become better parents. Family Recovery Court hearing is full of support and encouragement in order to create an atmosphere that’s welcoming, while also balancing accountability. Before each Family Recovery Court hearing, there is a ‘staffing’ where all criminal justice actors meet to discuss all of the participants appearing before the court that day. Within these discussions, there is a collaborative approach towards making a decision on whether an individual shall receive an incentive for their progress, or a sanction for an unaccepted behavior. If a participant has made significant achievements in their treatment programs and continues to display sufficient efforts to overcome their substance abuse, they are then advanced to the next phase and given praise from the courtroom while being honored with a sobriety medallion awarded by the Judge.

However, if a participant is falling behind in their treatment, or has missed drug testing, the judge may order a sanction which may include holding them back from advancing onto the next phase. This is due to the complexity of the recovery process and the amount of issues that can cause a potential for relapse. Addressing individual issues of each participant is essential to the successful completion of each phase, and once the program is completed their case is closed with Family Recovery Court. This means that they no longer have access to the FRC team who helped them through recovery, which has the potential for participants to feel unstable. Therefore, the Family Recovery Court team strives to ensure that all participants are moving through the program as effectively as possible. This means that if a participant needs more time to complete a particular phase, it’s usually granted. Most of the time, these issues are deeply rooted in their personal belief systems as well, such as developing healthy boundaries. These problems can take much more time to master than 9 months, which is the entire length of the program, so it’s crucial for the FRC team to strategically decide if a participant is ready for advancement. A participant’s child welfare case remains open even after their FRC case is closed.

This allows DCFS to continue their wellness check-ins with the children and the family unit’s functionality. Participants are also able to stay connected with USARA after graduation, so that they have an ongoing community of sober individuals they feel connected to even after completing Family Recovery Court. They do not entirely lose all of their support, but the routine they once had of attending treatment and attending Family Recovery Court frequently is no longer available. That change and transition can be difficult when calculating the long-term success of this program. Having their DCFS case open after graduating from FRC, because they continue to do check-ins with the family, has the potential to help parents maintain their sobriety long-term in comparison to the previous model, which closed both the FRC and DCFS cases simultaneously.

The Family Recovery Court handbook is crucial to participants because it provides them with a consistent tangible guide that outlines the expectations, available resources, and tools they can use throughout each phase of the program. The handbook is essentially a roadmap for the participants to follow and helps them initially understand the standards they are being held to before voluntarily joining Family Recovery Court. This is so that participants are fully aware of the requirements, and it can be reinforced at any time to ensure effectiveness of the model and the outcomes.

Theoretical Framework

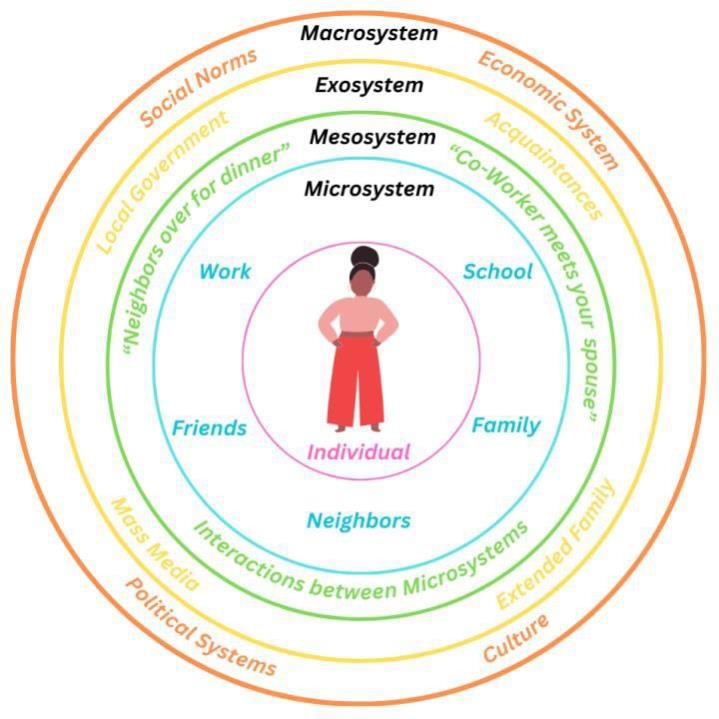

Ecological Systems Theory, developed by psychologist Urie Bronfenbrenner (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) is a scientific theory that explains how human development is influenced by the many environmental systems people encounter throughout their lives. The pattern follows a circle of influence model, with an individual at the center and outer influences encircling them, including family. Factors that influence an individual may include social settings outside of the home such as work, school, and community engagement. Within the visual model, see figure 4, there are four systems, which include the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem. The innermost layer, otherwise known as the microsystem, represents the immediate environment with which an individual interacts. These are the settings that directly influence an individual’s day- to-day life including their home environment, immediate family dynamics, neighborhood community relationships, and teachers or classmates in a school setting. The mesosystem is the next layer, and involves the connections or interactions between different microsystems. It references how various components of a person’s life such as their family, school, and peer group interact and influence one another. This is usually identified as the relationship between elements of the microsystem, such as when you bring a friend home from school, or when you bring a spouse to a work event, which is important since the mesosystem can either enhance or hinder development. The exosystem is the next layer which expands the ecological system and consists of broader settings where the person is not actively involved but decisions, policies, or events can still have a direct impact. For instance, a parent’s job may influence family time, economic resources, or stress levels which can then affect the child within the home. Lastly, the macrosystem refers to the overarching cultural, societal, and economic systems that shape the system as a whole. These include cultural beliefs, laws and policies, or economic and political systems which have much broader influences, but they are still significant to the ecological system.

Figure 4. Depiction of Ecological Systems Theory

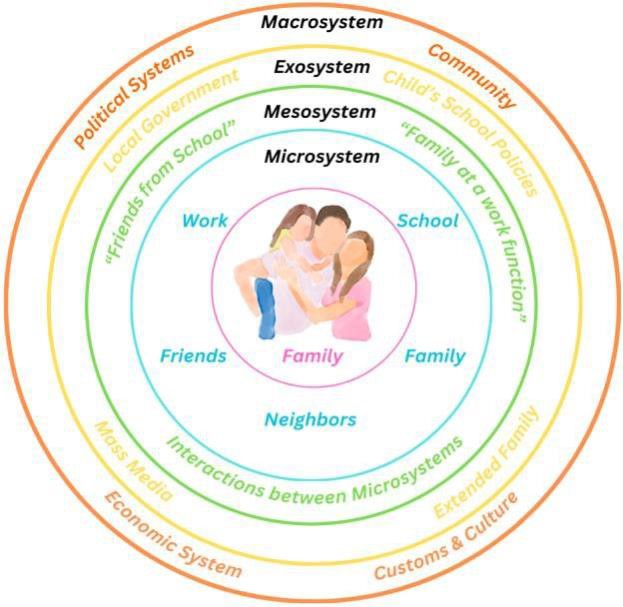

When this research theory is applied to families, see Figure 5 with family now at the center, the focus is on the environmental status of families and how they are influenced through interactions within their surrounding environment (Lamanna et al., 2021). The microsystem is their home life, the mesosystem is the family’s role in society, then the exosystem is the family’s informal social networks, and the macrosystem is the larger contextual factors.

The microsystem of the family includes the home life of a family, their natural environment, such as their home, and a human-built environment, such as their neighborhood community. In the microsystem these are the elements which directly influence the family’s interactions because they engage in these daily. These tend to have the biggest impact on family behavior, routines, and dynamics.

Within the mesosystem, the family’s role involves balancing what the parents and children need in regards to other environments, such as school or work in relation to their life at home. Families often have to consider the schedules of other members within the family unit and make adjustments accordingly. For instance, a child’s school schedule may conflict with a parent’s work schedule, requiring additional care or supervision from an outside source. These arrangements create additional obstacles for a family that are otherwise not applicable to a single individual when considering multiple members of a family unit. The mesosystem emphasizes how these different microsystems like school, work, and home interact with each other to support a family function smoothly. All of these environments, including school, work, and community relationships often create a family’s informal social network which is made up of interactions including extended family, social groups, and recreational activities.

The exosystem of the family includes more indirect influences such as extended family relationships, and mass media exposure that can affect the family’s daily functioning and values. These are not the most immediate elements that affect a family, but are still impactful areas of a family’s daily functions because families rely on this layer for outside information beyond their inner circle. A primary example of this would be a local government decision to close down a library or community center which could limit a family’s access to educational resources.

Lastly, the macrosystem includes contextual factors such as limited resources that may impact how families maintain their lifestyle based on the culture of their surroundings such as political systems and social norms. This reflects how the macrosystem layer comprises cultural values, laws and even economic systems that impact which resources are available to families of low socio-economic status. For example, receiving news from their state about child tax policies and statewide school policies may directly affect them. All of this is to say that families are a byproduct of their surroundings.

Figure 5. Depiction of Families at the Center of the Ecological Systems Model

However, how do community resources impact our connections with those around us? Are good social connections important to the decisions we make in our everyday lives, and are they a driving factor for how we choose to live? Ivan Nye’s Social Control Theory suggests that people are influenced by society through their social bonds in three distinct ways (Nye, 1958). Internal control refers to the internalized norms, values, and consciousness of the collective society that guides an individual’s behavior. Indirect control is linked to an individual’s emotional bonds with others, such as family members, friends and close social groups. Direct control involves external measures that prevent deviant behavior, such as rules, laws and supervision. Nye hypothesized that individuals who are more attached to society by means of employment, family, and friends are most likely to act in positive ways in order to maintain their social relationships. However, the opposite is true for those who are not attached to society; they are more likely to act in antisocial behavior including engaging in criminal activity (Cullen & Wilcox, n.d.). For instance, if a person has no employment, has not contacted their family in several months, and their current circle of influence are only individuals with substance abuse disorders, they may be more likely to engage in that behavior as well. On the other hand, if a person has stable employment, they are consistently connected with their family, and they are surrounded by individuals who are sober while doing shared activities, they are more likely to engage positively in society.

Both Ecology Systems Theory and Social Control Theory overlap in regards to the sociological factors of an individual’s environment in a social-cultural context. The majority of the participants in Family Recovery Court have been exposed to an environment of substances from an early age and this could lead to similar antisocial patterns within their own life. In order to break generational hardship, it takes removing the individual entirely from their environment and connecting them to alternative resources that foster positive outcomes and success.

These theories both conclude that structures are fundamental in sustaining our lifestyle and the ways in which we choose to live it; but ultimately, changing the structure causes everything else to shift. Both theories emphasize the importance of social contexts, such as Ecological Systems Theory which focuses on the different layers of environmental influence from immediate family to broader societal systems. Whereas Social Control Theory stresses the importance of societal bonds and the consequences of having weak social connections. Together, they suggest that when individuals are surrounded by antisocial environments, their behavior can also become antisocial. However, providing individuals with positive social bonds or environments fosters healthier connections and relationships. Both theories suggest that individuals can be redirected toward healthier more socially acceptable behaviors, showing that change in external structures can lead to shifts in behavior and better outcomes.

Research Questions

Based on these theories, the assumption is that individuals who have been surrounded by antisocial environments for the majority of their lives have potentially engaged in similar behaviors that have led to their participation in Family Recovery Court. I hypothesize that if individuals in Family Recovery Court are offered positive influences of social support (mentorship and sober support groups), or they are directed towards external sources of controlled healthy environments (in-patient treatment), then they may begin to engage in prosocial behaviors that lead to more successful outcomes (sobriety, reunification, etc..) based on those influences. I am interested in understanding further which specific forms of social support and/or treatment lead to the most successful outcomes for participants of Family Recovery Court. Additionally, I hypothesize that an individual may be the most successful when they have a true desire to change. If an individual feels that they are forced into participating in Family Recovery Court, will they have the necessary commitment to success? I expect to see that a combination of the support given and a participant’s internal motivation are both necessary for success in Family Recovery Court.

Methods & Data

Throughout the research process, two methods of data collection were utilized including six-months of court observations and a total of seven interviews. As a previous intern for the 3rd District Juvenile Courts, I was able to gain behind the scenes access to court procedures during Family Recovery Court staffings and hearings. I diligently wrote down my personal observations and questions in a journal, which I dated each time I entered the courtroom. After my internship was complete I remained in close contact with several staff who worked in Family Recovery Court. I interviewed these public servants of Family Recovery Court at the courthouse, in a conference room next to the courtroom in which FRC hearings took place. There, I successfully gathered seven interviews with a judge, DCFS Case Manager, Treatment Coordinator, Licensed Clinical Social Worker, USARA Peer Coach, Parental Defense Attorney, Guardian Ad Litem, and an Assistant Attorney General; each ranging between 15-45 minutes. Each participant was asked the same set of questions about the effectiveness of Salt Lake City’s 3rd District Family Recovery Court. They were also asked to provide details on the specific resources, outcomes of cases and success of FRC. This provided a well-rounded approach to the general functionality and impact that this program affords its participants.

Throughout the research process, the Grounded Theory Approach (Corbin & Strauss, 2014) was utilized as well, to consider the rapid changes that may occur within a person, group or setting such as Family Recovery Court. Grounded theory allows for the researcher to objectively build theories based on the data that enables an explanation, and is considered grounded in the actual experiences and perceptions of the participants. Describing, understanding and analyzing the data through a theory that has been formulated based on the data provides a more holistic approach to the research (Morse et al., 2021). Through this method, Family Ecological Systems Theory and Social Control Theory were identified as applicable frameworks to help explain the mechanisms of support, accountability, and behavioral change observed in Family Recovery Court.

Findings

Based on my interviews, several key themes emerged that are central to understanding the effectiveness of Family Recovery Court. These include the resources, outcomes and success of the program. I am utilizing these themes to explore which resources the program offers that lead to various outcomes, and successful long-term reunification of families.

Resources

Resources refers to the general supply of money, materials and staff available for participants in Family Recovery Court. Based on my observations and interviews, they all point to the critical role of the available resources offered to participants, whether that is in the form of social support, mentorship, peers, or even scheduled family visits with

DCFS. These resources seem vital in leading to positive outcomes and success in a participants case with FRC. For instance, the following organizations, that were mentioned throughout the several interviews and within most of my observations, were particularly important to a participants’ success. An organization that partners with Family Recovery Court is the Utah Support Advocates for Recovery Awareness (USARA). They are a non-profit organization based out of Salt Lake City that focuses on the social support of recovery by establishing a community of individuals dedicated to a life of sobriety. USARA is crucial, because it helps create a sense of community for individuals in recovery.

This Assistant Attorney General who works in Family Recovery Court said,

I am a big fan of USARA. I think setting these people up for success. We don’t want to, like they used to say, ‘treat you and street you’, which is kind of what I think we used to do.

The phrase used in this interview “treat you and street you” is the Attorney General referencing a past practice where participants in FRC who struggled with substance use disorders would be given treatment but then left to face the challenges of their recovery without continued support once their treatment had ended and their case was closed. This approach led to high relapse rates, because individuals were not being provided the necessary resources or guidance to maintain their sobriety and progress.

The Licensed Clinical Social Worker also mentioned the variations of mental health resources offered to the participants in regards to therapy.

…I mean, most of our clients have co-occurring mental health…, like, pretty significant trauma. Like, I think having therapists specifically to address that.

Peer support is a known factor in addiction recovery (Tracy & Wallace, 2016) so having the support of others who have navigated similar challenges is impactful for participants. Participants are more likely to stay committed to their recovery goals with this influence which translates into greater success and personal outcomes.

One of the main comments I received throughout my interviews was the court’s direct affiliation with USARA, as the DCFS Case Manager pointed out in this comment;

They can get peer support from AA or NA or, yeah, wherever they choose. But USARA is right there! Yeah, so a lot of them choose USARA, but top of the list is support.

Intermountain Therapy Animals is an additional resource that various courtrooms throughout Utah utilize during court proceedings. This non-profit organization provides animal therapy to participants every other week during FRC hearings, to aid in mitigating the stress of coming to court. Animal therapy can be a powerful resource, because it provides emotional comfort and reduces anxiety (Morrison, 2007) especially with the presence of trained animals who are there during FRC hearings. Participants can receive a calming presence during potentially overwhelming court proceedings, which allows them to better focus on their case and it creates a space for them to build emotional resilience which can be impactful to their case.

There are also Parent Advocates who work in conjunction with the parental defense team to provide additional legal support as these parents navigate the legal process. Parent Advocates are an invaluable resource because they can offer guidance to participants through the legal system, to mitigate overwhelming feelings. These advocates not only provide emotional and legal support, but they also ensure that parents understand their case and how they can make informed decisions throughout the process. Parent advocates provide support and understanding, making sure that the participants in FRC feel heard and empowered. This directly impacts the success of their cases, since participants are more likely to succeed when they feel confident in understanding their case and they are backed by someone who acknowledges their circumstances.

A Licensed Clinical Social Worker and DCFS case manager are also appointed for each participant to advocate for their mental health and provide general support. These professionals are critical to the advocacy of mental health and well-being of the participants in FRC, because they provide tailored support to each individual’s needs. They ensure that participants receive the therapeutic services they need to address trauma, substance use, and other mental health concerns. LCSWs and DCFS case managers assist with identifying mental health needs, facilitating treatment, and ensuring that participants are engaged in those recovery and therapy services. Essentially, they act as case managers who track the participants’ progress and make sure that they are getting the services they need which is extremely impactful for success in recovery.

Lastly, a treatment coordinator from House of Hope, which is an in-patient treatment facility for women and children, where they can give direct support to those participants who are in their program and on the participants’ involvement with treatment. Even if a participant is not at House of Hope, the treatment coordinator can offer broad perspectives for those going through treatment, and give suggestions to the court to help them. Even if a participant is in a different treatment program, the treatment coordinator’s position is to bring forth solutions to participants experiencing issues in treatment. This could include helping the participants identify barriers to success, such as emotional or psychological, and collaborate with the treatment facility to address those obstacles. Addressing potential barriers to treatment, such as lack of transportation, mental health issues, or difficulty with treatment compliance, has an impact and is a direct correlation to a participant’s completion of FRC.

Even a Parental Defense Attorney shared their perspective on all of the social support from each party in Family Recovery Court stating,

I think FRC works really well for parents who need social support. I think that’s the primary benefit I’m seeing from it. All the other little things that go on, and I don’t know how helpful or not they are, but that it’s parents who want to make changes in their lives, but don’t have a good support, social support network. I think FRC is fantastic for them. Okay, people who have mental health issues, people who are struggling in addiction and are still trying to figure out if they want to make that change in their life – I don’t think FRC really helps them at all. But people who want to make those changes and and just, frankly, need a support network, because they just have themselves, yeah, and don’t have a lot of skills, and don’t have…anyone to fall back on, I think those people do fantastic …and I think they’re the ones that get the most out of it.

FRC also aids participants in gaining quick access to a treatment facility and getting connected with all of the above resources in a fast-tracked manner that would otherwise take several months for them to achieve on their own accord. This is just one of the many additional benefits that Family Recovery Court has to offer its participants, to ensure a successful graduation and reunification with their children.

The amount of resources offered through Family Recovery Court lays a strong foundation for success. However, when examining the outcomes, both short and long- term, the true impact of these resources becomes more prominent. If a participant is maintaining their sobriety, gaining family reunification, and experiencing personal growth, it’s apparent how much support these resources truly offer.

Outcomes

An outcome refers to the way a situation turns out and is the result or consequence of action or inaction. There are four potential outcomes for participants of FRC, including: graduating from the program with a successful reunification, graduating without a successful reunification, being discharged without graduating, or graduating with a successful reunification but then returning to the program after a relapse.

Graduating from the program with a successful reunification is when a participant is able to complete up to 6 months or more of Family Recovery Court, while simultaneously closing out their child welfare case with DCFS. This typically involves a separate court process, where the judge reviews their progress in FRC and considers the efforts they are making to reunify with their children.

However, not all participants who graduate from FRC are successfully reunified with their children. This could happen because timelines were not met based on the state’s standards. DCFS timelines and FRC timelines do not always match up, and if a participant is coming into the FRC program toward the end of their DCFS reunification timeline, it may not be enough time for a successful reunification. However, they will still be able to participate in FRC and graduate from the program.

If a participant is discharged from FRC, this is due to the judge determining that the participant has not made sufficient progress. Some examples of why a participant could be discharged include, but are not limited to: if they continue to test positive or dilute on their scheduled urinalysis tests, if they are not following their scheduled visits on their child and family plan from DCFS, or they have missed several scheduled urinalysis tests.

Family Recovery Court participation is voluntary, meaning participants can leave at any time. If they voluntarily leave, the decision for their potential return would be assessed on a case-by-case basis. In most cases, participants who leave will have limited time available to re-enter and successfully complete the program. However, being discharged from Family Recovery Court is a result of insufficient progress or failure to meet the program’s requirements, although judges typically show more support towards participants who are regularly attending and earnestly attempting to follow the program’s guidelines.

While Family Recovery Court focuses on providing an encouraging environment for participants, there are challenges with certain outcomes that can limit the overall effectiveness of the program for certain individuals. For instance, the issue of finding balance between holding participants accountable for their recovery and offering them the time and support needed to genuinely transition. There is an ongoing debate about leniency versus strict enforcement of the rules, especially when it comes to handling setbacks like failed urinalysis tests or other relapses.

When a judge adopts a zero-tolerance policy, it can create an environment where participants feel pressured, leading to discouragement rather than motivation. Some interviewees argued that the program should allow more time for participants to get sober and make necessary adjustments without facing immediate punitive actions such as sanctions. In a system that is supposed to be empathetic toward the personal circumstances of each participant, overly rigid practices can harm the program’s goals. There was a situation where one participant was discharged from the program by a single judge, despite having been in the program for several months. This was the only instance of a discharge I witnessed during my time as an intern for Family Recovery Court, and it raised concerns about how strict some judges interpret the rules. This particular participant, let’s call him Alex, had struggled to produce clean urinalysis results, continuously testing positive. While Alex’s struggles were clear, the outcome felt somewhat harsh when compared to how other judges handled similar situations with more empathy and understanding. It became clear that inconsistency in how different judges applied policies can have a profound impact on a participant’s chances for success, and ultimately limited Family Recovery Court’s ability to offer the rehabilitative environment necessary for long-term recovery outcomes and ultimately, family reunification.

A DCFS Case Manager shares her knowledge in an interview on her experiences working with participants in Family Recovery Court stating,

It’s just, they’re just not ready. Because, like I think addiction is so powerful that you know if somebody’s just going along on their case, but then you got another person in FRC. The FRC person doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re going to be successful, versus this person. It I feel like it’s a 50/50, with the support we give them, versus also, if they’re ready.

A participant’s child-welfare and criminal cases are still on-going simultaneously throughout their Family Recovery Court case, and if they are discharged from FRC their other cases still continue as if nothing changed. The main drawback is that the judge handling their child welfare case may view their discharge from FRC negatively.

Another possible outcome is if a participant relapses after already participating in the program and graduating, but then returns in order to gain reunification status once again. In Salt Lake City’s Third District Family Recovery Court, participants who are discharged typically cannot re-enter the program, as discharge generally indicates that they are no longer eligible due to not meeting the program’s requirements or other reasons. However, if a participant leaves the program voluntarily (rather than being discharged), it might be possible for them to return, but this would depend on the circumstances, the rules of the program, and the court’s decision.

These are often the reasons that a prior participant might come back to FRC: the death of a loved one, unemployment, intimate partner violence, or the participant experiences mental health concerns, any of which could cause a relapse. If a participant returns to the program, they must go through the process as if it were their first time, and complete at least 6 months of FRC before graduating.

In some cases, a participant may be able to request to rejoin the program after voluntarily leaving, but they would need to demonstrate that they have addressed the issues that led to their departure. Ultimately, this decision would be up to the judge or the court’s discretion, based on the individual’s progress and the specifics of the situation.

A participant may be able to technically complete the program by checking off all the requirements for FRC, however, they must carry what they’ve learned from their participation after they’ve graduated; because there is no guarantee that an individual’s participation in FRC will result in a successful reunification. The child welfare system abides by a strict and rigorous timeline that has limitations which does not guarantee a parents rights to reunification if they do not meet those deadlines. There are no limits to the amount of times that an individual may participate in Family Recovery Court as long as their child welfare case has granted reunification rights. The main difference between outcomes and success is whether a participant continues to carry healthy habits long after graduating from the program. Their willingness to engage in all of the resources that Family Recovery Court has to offer, determines their particular outcome and the level of success that they will achieve even after graduating from the program.

Success