College of Social and Behavioral Science

126 Rewriting Reality: Cognitive and Affective Relationships of Counterfactual Thought

Petr Horgos

Faculty Mentor: Jared Branch (Psychology, University of Utah)

ABSTRACT

Counterfactual thinking (CFT) is the mental process of imagining alternative outcomes to past events by considering how things might have turned out differently. These imagined alternatives can vary in direction: upward CFT (uCFT) involves thinking about better outcomes, while downward CFT (dCFT) involves imagining worse ones. uCFT often evoke regret or motivation to improve, whereas dCFT tend to elicit relief or serve to justify past actions. CFT may become distorted or dysregulated during periods of heightened negative affect. Increased CFT has been linked to greater symptom severity in mood-related mental health conditions. Since CFT relies on reflecting on past experiences, most research has focused on its connection to negative events. However, individuals may differ in their general tendency to engage in CFT, regardless of context. This study examined how dispositional CFT directionality relates to psychological distress, rumination, and affect. A sample of 314 participants completed self-report measures assessing CFT frequency and directionality, depression, anxiety, stress, rumination subtypes, and positive and negative affect. Correlational analyses showed that both uCFT and dCFT were significantly associated with psychological distress and negative affect, with uCFT showing stronger correlations. Rumination, especially brooding and depressive thinking, had the most robust associations with both CFT directions. Regression analyses identified brooding as the strongest predictor of uCFT, while dCFT was best predicted by uCFT and anxiety. When rumination was statistically controlled, distress measures no longer significantly predicted CFT. These findings highlight cognitive style, particularly rumination, as a key factor in counterfactual thinking.

Rewriting Reality: Exploring the Cognitive and Affective Relationships of Counterfactual Thought

What if… If only…

Throughout life we inevitably encounter unpleasant events which we wish could have turned out differently, be it an unexpected parking ticket or the loss of a loved one. In times of distress, we often resort to pondering the actions that could have altered the course of events. This mental simulation, which generates an alternative outcome to a past event, is known as counterfactual thinking (CFT). The Functional Theory of Counterfactual Thinking posits that CFT, at its core, is a problem-solving mechanism which is activated when reality deviates from an ideal reference state (see for discussion, Roese & Epstude, 2008). This comparative cognitive mechanism is widespread and may be critical to human social-cognitive functioning and intelligence (Hofstadter, 1979; Miller et al., 1990). It influences how people make causal attributions (Gavanski & Wells, 1989) and approach problem-solving (Roese et al., 1999). Additionally, it affects motivation, mood states, and behavior (Markman & McMullen, 2003; Markman et al., 2008; Roese, 1994).

The simulation of a better imagined outcome is termed upward counterfactual thinking (uCFT) and is generated to identify mistakes when a goal isn’t achieved, helping to shape future intentions and improve the chances of success (Markman et al., 1993; Roese et al., 1999). A classic example would be, “If only I had studied, then I would have passed my exam”, which serves to identify a causal relation between an actionable alteration in a past scenario towards a more beneficial outcome (Roese, 1993). As a distinctly problem-focused cognition, uCFT is the most common form of CFT – both in everyday life and following negative outcomes (Nasco & Marsh, 1999; Roese & Hur, 1997; Roese & Olson, 1997).

While upward counterfactuals can promote learning and improvement, they may also elicit negative mood states (Roese & Olson, 1997). By imagining how things could have gone better, individuals draw a sharp contrast between the actual outcome and a more desirable alternative. This contrast can intensify feelings of regret, disappointment, or frustration, especially when the better outcome seems attainable (Markman & McMullen, 2003). As a result, upward counterfactuals may temporarily lower mood or self-esteem, even as they encourage future goal-directed behavior.

The mental simulation of a counterfactual does not necessarily evoke a favorable outcome, however. Downward counterfactual thinking (dCFT) simulates worse imagined outcomes (e.g., “At least I only sprained my ankle—if I had fallen a little harder, I could’ve broken it.”). dCFT may serve an important affect regulation function by helping individuals manage their emotional responses to negative events. Research has shown that generating dCFT is associated with improved mood following distressing experiences (Sanna et al., 2001; Wegner et al., 2001, as cited in Byrne, 2016). By highlighting more adverse alternatives, dCFT can reduce the perceived severity of an event, offering psychological relief and promoting emotional resilience. dCFT may serve an affect regulation function, with the generation of dCFT linked to improved mood following a distressing event (Sanna et al., 2001; Wegner et al., 2001, as cited in Byrne, 2016).

Although CFT is both common in everyday life (Sanna et al., 2003) and present across nations and cultures (Gilovich et al., 2003; Liu, 1985; Roese, 2008), no standardized measure exists to ascertain dispositional tendency to engage in CFT. A variety of counterfactual measurement techniques have been previously developed, which attempt to explicitly elicit counterfactual generation in reference to a simulated or hypothetical event (see Miller et al., 1990, for a review). A past technique, asking participants to consider how hypothetical outcomes could have been different (i.e., housing an injured bird in your room only to have it die because you had left your air conditioner on high), is one such example (e.g., Gavanski & Wells, 1989; Niedenthal et al., 1994; Roese, 1994).

In another method, participants were asked to decide which of the protagonists in a vignette would more intensely experience a counterfactual emotion, such as regret (e.g., Gleicher et al., 1990; Kahneman & Tversky, 1982; Landman, 1987, as cited in Rye et al., 2008). A third approach required participants to “think out loud” while performing various tasks such as a blackjack task. CFT would then be identified by researchers (Markman et al., 1993). In the same vein, another approach involved asking participants to read vignettes while indicating their emotional responses using semantic differential scales (Boninger et al., 1994; Macrae, 1992; Macrae & Milne, 1992; Miller & Gunasegaram, 1990; Miller & McFarland, 1986; Turley, Sanna, & Reiter, 1995, as cited in Rye et al., 2008).

A recent attempt at the development of a counterfactual thinking scale, the Counterfactual Thinking for Negative Events Scale (Rye et al., 2008), was designed to assess counterfactual production following an intense negative event (i.e., death of a family member). This focus on major life events overlooks the fact that counterfactual thoughts may be generated in response to more mundane, everyday occurrences—such as getting a parking ticket, arriving late to a meeting, or missing a turn while driving (Branch, 2023; Sanna & Turley, 1996). These events may not be emotionally overwhelming but still trigger upward or downward counterfactual that influence future behavior and mood regulation. Consequently, limiting measurement to highly distressing or infrequent events may fail to capture the routine and often automatic nature of counterfactual thinking in daily life. A scale that measures dispositional tendencies to engage in uCFT and dCFT, regardless of event severity, would provide a more comprehensive understanding of how people habitually generate and rely on these mental simulations across contexts.

Though useful, past methods have distinct limitations to the application in future research. A central limitation is the use of labor-intensive methods requiring the training of and facilitation by a rater (for an example, see Roese & Olson, 1995a). Further, past methods are reliant upon open-ended measurement formats in which the participant identifies and reports a discrete counterfactual thought to a rater (see for an example, Roese & Olson, 1993). In cases where the participant struggles with counterfactual identification, this may enable reporting error of counterfactuals and subsequent diminished report of counterfactuals (for a discussion, see Rye et al., 2008).

The present study to assessed whether dispositional uCFT and dCFT show differential associations with cognitive and emotional factors previously linked to event- related counterfactual thinking. Specifically, we examined how the frequency and directionality of counterfactual thoughts, as measured by the Autobiographical Counterfactual Thinking Scale (ACTS; Branch et al., manuscript in preparation), relate to levels of positive and negative affect (measured by the I-PANAS-SF; Thompson, 2007), psychological distress (e.g., depression, anxiety, and stress; measured by the DASS; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995), and rumination (measured by the RRS; Treynor, 2003). If tendencies toward uCFT or dCFT are found to correlate with distinct emotional or cognitive patterns in response to life events, these findings could inform the development of targeted cognitive interventions. Such interventions might help individuals reframe maladaptive counterfactual thinking styles and promote more adaptive coping strategies in everyday life.

Correlates of Counterfactual Thinking

Positive and Negative Affect

Counterfactual generation serves two general functions: mood regulation (Markman & McMullen, 2003; Zeelenberg & Pieters, 2007) and preparatory adaptation for future events (Markman et al., 1993, 2008; Roese et al., 1999). Counterfactuals, as a functional cognitive mechanism, are typically preceded by a failure state – that is, they are activated via the onset of negative affect which acts as an error identification system (Lieberman et al., 2002; Roese & Olson, 1997; Schwarz, 1990). Once an error is identified, a counterfactual thought is produced with the resulting affective change dependent on the direction of the counterfactual. Future behavior regulation is associated with uCFT (Markman et al., 2008), serving an adaptive function in the face of negative outcomes, however, uCFT also leads people to experience negative emotions (Epstude & Roese, 2008; Roese et al., 1999). Further, inductions of negative mood states have been found to heighten CFT, particularly uCFT (Sanna, 1998). dCFT typically has the opposite effect on emotional state; these thoughts may promote positive affect following generation (Feeney et al., 2005), though in instances of extreme negative affect, dCFT relates to vividness, frequency, and subsequent experience of distress (Blix et al., 2018).

The relationship between affect and CFT is reportedly reciprocal (Markman et al., 1993; Roese & Olson, 1997). Just as affect may elicit CFT, CFT may also produce affective change. This may be achieved by two cognitive processes: affective contrast or assimilation. Via affective contrast effect, a judgment may become more extreme through the juxtaposition of a better imagined outcome and the factual outcome, making the factual outcome appear more negative (McMullen, 1997; Roese, 1994). Olympic bronze medalists, for example, feel happier with their outcome than silver medalists despite being in an objectively inferior position (Medvic et al., 1995). Conversely, affective assimilation contrast arises when an individual mentally simulates a worse alternative outcome and momentarily adopts the emotional perspective associated with that imagined scenario (McMullen, 1997).

Depression

Despite their evaluative and regulatory benefits, counterfactual thoughts may be subject to distortion or inaccuracy (Roese & Olson, 1993a; Sherman & McConnel, 1995). In severely depressed individuals, counterfactual thoughts are divorced of accuracy and produce unreasonable insight; though lacking in functional character, these thoughts were still emotionally unpleasant (Markman & Miller, 2006). The proclivity of depressed individuals to engage in concerted contemplation of negative life events leads to increased comparative thoughts (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000). Feng et al. (2015) found that depression severity positively correlated with the activation frequency of a brain biomarker sensitive to comparison between subjective expectation and reality in counterfactual thought eliciting trials. Regardless of directional elicitation, this suggests increased generation of counterfactuals in depressed individuals. Further studies have demonstrated positive associations of increased CFT and depressive symptoms, with increased uCFT exhibiting particularly strong positive correlation to depressive symptoms (Broomhall et al., 2017; Tagini et al., 2021).

Anxiety

Prokopčáková and Ruiselová (2008) identified that most individuals utilize upward CFT as a problem-solving tool and believe it to be a useful cognitive mechanism. Nevertheless, the attitudes towards CFT in highly anxious individuals are an exception, as highly anxious individuals rated CFT as less useful than their non-anxious counterparts. In the same study, increased anxiety correlated with heightened CFT and negative traits like rumination (Prokopčáková & Ruiselová, 2008). Individuals with higher levels of anxiety show an increased inclination towards the production of counterfactuals (Branch, 2023; Ruiselová et al., 2007; Tagini et al., 2021). This may stem from the excessive error monitoring characteristic of anxiety (Moser et al., 2013), leading to increased generation of problem-focused cognitions (Parikh et al., 2022). In participants with high social anxiety, Rachman and colleagues (2000) found increased consideration of potential past failures (retroactive error monitoring) and inadequate behavior in social interactions resulting in increased generation of uCFT. Tendency towards and the duration of uCFT, likewise, correlate positively to presence of high anxiety (Callander, 2007).

Stress

Distressing recollections of traumatic incidents play a crucial role in both the emergence and persistence of posttraumatic stress responses (Rubin et al., 2008). Prior studies indicate that individuals experiencing elevated levels of post-traumatic stress tend to have more intense memories of the traumatic experience, characterized by stronger sensory details and heightened emotional re-experiencing compared to individuals with lower post-traumatic stress levels (Berntsen & Rubin, 2006; Rubin et al., 2008). Conditions characterized by an extreme stress response, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and post-traumatic stress reaction (PTSR), have also been associated with CFT (Blix et al., 2018; Gilbar et al., 2010). For instance, after stress-producing events, such as terror attacks, counterfactual production is prevalent and predictive of severity of emotional response. Duration and vividness of CFT appear to play an important role in the development of stress symptoms (Blix et al., 2018). Additionally, counterfactual thoughts were found to be positively correlated with general level of stress (Branch, 2023; Davis et al., 1995).

Rumination

Martin and Tesser (1996) defined rumination as unintended, intrusive thoughts which are not relevant to a salient task. Though many researchers consider CFT to be a subset of rumination, the two are distinguishable by their orientation, or lack thereof, to a goal (see for discussion Roese & Olson, 1997). Simply, CFT simulates alternatives of events whereas rumination is a simple repetition of the real event (Davis et al., 1995). Rumination involves self-focused assessment as a means of coping which may be affected by mood valence (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Treynor, 2003). Previous research has found higher rates of CFT positively correlate to level of rumination (Branch, 2023; Prokopčáková & Ruiselová, 2008). Reflection, a subfactor of rumination, may be characterized as neutrally valanced contemplation that seeks to adapt to difficulties. On the other hand, brooding, a negatively valanced rumination subfactor, is often rife with localized self-critical thoughts (Treynor, 2003). Similarly, depression-related rumination is a negatively valanced ruminative style focused globally on negative life-outcomes. Increased counterfactual generation is positively correlated with each subtype, although the strength of correlation is greatest in the brooding subtype (Branch, 2023).

Summary of Hypotheses

H0. Past research has established that upward counterfactual thinking is more common than downward (Nasco & Marsh, 1999; Roese & Hur, 1997; Roese & Olson, 1997), and counterfactual production is chiefly activated by negative mood states (Roese & Olson, 1997), indicating that negative emotions may trigger a greater focus on how situations could have been improved rather than worsened. In light of this evidence, we predict that negative affect will positively correlate with general counterfactual production but show a stronger correlation with upward counterfactual thought than downward counterfactual thought.

H0a. Negative affect will be positively associated with upward counterfactual thinking, as individuals experiencing distress tend to focus on missed opportunities and how situations could have improved (Roese & Olson, 1997). These upward comparisons are more likely to elicit regret and signal behavioral change (Markman et al., 1993).

H0b. Negative affect will also be positively associated with downward counterfactual thinking, but to a lesser extent, as these thoughts may serve a mood-buffering role that is less frequently accessed when negative emotions dominate (see for discussion, Roese & Epstude, 2008).

H1. Positive affect will be negatively correlated with overall counterfactual thinking. Specifically, we hypothesize that positive affect will show a stronger negative correlation with upward counterfactual thinking than with downward counterfactual thinking. This may be due to the mood-congruent processing tendency, where individuals in positive moods are more likely to focus on favorable outcomes and maintain their affective state by avoiding regret-inducing upward comparisons (Markman & McMullen, 2003). As a result, upward counterfactual thinking—which often highlights missed opportunities— may be particularly incongruent with the emotional goals of those experiencing positive affect and therefore show stronger negative associations.

H1a. Positive affect will be negatively correlated with upward counterfactual thinking, as these comparisons emphasize better alternatives and contradict the goal of maintaining a positive mood (Markman & McMullen, 2003).

H1b. Positive affect will also be negatively correlated with downward counterfactual thinking, though the relationship may be weaker, as downward comparisons may be compatible with mood maintenance and self-enhancement.

H2. Depression, characterized by chronic negative affect, difficulties disengaging from negative material, and deficits in cognitive control when processing negative information (Gotlib & Joormann, 2010), will be positively correlated with both upward and downward counterfactual thinking. However, this correlation will be stronger for upward counterfactual thoughts, as depressive individuals may be more prone to focus on how they could have done better or avoided negative outcomes (Feng et al., 2015).

H2a. Depression will be positively associated with upward counterfactual thinking, reflecting depressive individuals’ tendencies to focus on failure, missed opportunities, and personal shortcomings (Feng et al., 2015).

H2b. Depression will also be positively associated with downward counterfactual thinking, though to a lesser degree, as these thoughts may not align with the self-critical and pessimistic mindset typical of depression (Gotlib & Joormann, 2010).

H3. General stress levels will positively correlate with the frequency of counterfactual thoughts, as stress often prompts individuals to mentally simulate alternative outcomes (Branch, 2023; Gilbar et al., 2010). This association is expected to be stronger for upward counterfactuals, as stressful experiences often lead to thoughts about how one might have improved a situation.

H3a. Stress will be positively associated with upward counterfactual thinking, as individuals attempt to mentally rehearse improvements to past events in hopes of reducing future stressors (Roese et al., 2009).

H3b. Stress will also be positively associated with downward counterfactual thinking, though to a smaller extent, potentially serving as a self-soothing mechanism in response to stress (see for discussion, Blix et al., 2018).

H4. Anxiety will be positively associated with both upward and downward counterfactual thinking, but more so with upward counterfactuals. This is because anxious individuals are more likely to engage in future-oriented, precautionary thought patterns that align with upward simulations of how a situation could have been better (Branch, 2023; Callander, 2007; Ruiselová & Prokopčáková, 2008).

H4a. Anxiety will be positively associated with upward counterfactual thinking, as these thoughts align with anxious individuals’ focus on prevention, risk, and how negative outcomes could have been avoided (Callander, 2007).

H4b. Anxiety will also be positively associated with downward counterfactual thinking, but this relationship may be weaker, as anxious individuals tend to focus on threat avoidance rather than consolation or relief-based thinking (see for discussion, Roese & Epstude, 2008).

H5. Rumination will show a positive correlation with both upward and downward counterfactual thinking, reflecting a general tendency toward repetitive, self-focused thought. However, this correlation will vary by rumination subtype: brooding and depression-related rumination will be more strongly associated with upward counterfactuals, while reflective rumination may show a more balanced or weaker pattern of association (Branch, 2023).

H5a. Rumination—especially brooding—will be positively associated with upward counterfactual thinking, as this form of thinking involves repetitive focus on how events could have turned out better, consistent with self-critical rumination (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008).

H5b. Rumination will also be positively associated with downward counterfactual thinking, particularly for reflective rumination (Branch, 2023), though the relationship is likely weaker than with upward counterfactuals.

METHODS

The goal of the present study was to examine the relationship between the Autobiographical Counterfactual Thinking Scale (ACTS) and measures of affective valence and thinking style. The included variables were selected based on the strength of evidence for their valid, reliable, and predictive relationship to counterfactual production and directional tendency (see Branch, 2023). This study was pre-registered on AsPredicted.org prior to data collection. The pre-registration included the study’s hypotheses, variables, sample size, and planned analyses to promote transparency and reproducibility: Available at https://aspredicted.org/k9z9-4vmy.pdf. All methodological decisions were determined a priori in accordance with the pre-registration. Determination of sample size was made via G*Power (Faul et al., 2009), indicating a sample size of 350 is sufficiently powered (80%) to detect medium (0.15) effect sizes (α = .05). It should be noted, however, that the analysis and subsequent results of the current paper were finalized prior to the collection of the intended sample size. Any deviations from the original plan are transparently reported in the relevant sections.

Participants

A total sample of 340 participants was recruited via the SONA undergraduate Psychology participant pool. To mitigate the effects of inattention, boredom, and fatigue, participants whose study duration fell above the 95th percentile or below the 5th percentile were excluded (n = 36; Jeong et al., 2022). A final sample of 314 participants (230 female, 84 male; mean age = 20.3, SD = 4.6, range = 18 – 59) enrolled at the University of Utah completed the study in exchange for course credit. The sample consisted of majority White participants (75%). Other ethnic groups included Latino(a) (10%), Asian, Asian American (9%), African American (1%), Pacific Islander (1%), and other/preferred not to say (4%).

Procedure

Informed consent was obtained online prior to the start of the study, wherein participants were informed of study objective: to construct and assess the validity of the Autobiographical Counterfactual Thinking Scale. Participants completed the study online at a location and time of their choosing. Assurance of adherence to ethical standards, potential risk (namely data breach), and researcher contact information were provided. As well, prospective participants were informed of compensation protocol. The average duration of study completion was determined by a pilot study to be 30 minutes. Per SONA guidelines, participants received 1 credit upon completion of the study. In the event of early withdrawal, participant credit was pro-rated by the ½ hour and awarded to the participant depending on individual time investment prior to withdrawal. Participants first reported demographics, including gender, ethnicity/racial group, and age. Participants were presented with each questionnaire in a randomized sequence. Each questionnaire was formatted on a single page. On average, participants required 16 minutes to complete the study.

Measures

Counterfactual Thinking

The Autobiographical Counterfactual Thinking (ACTS; Branch et al., manuscript in preparation) is a 10-item measure that differentiates upward counterfactual thinking (e.g., “I think about personal events and how they could have been better”) from downward counterfactual thinking (e.g., “I find myself thinking about my past and how it could have been worse”) to obtain a general measure of counterfactual directional tendency and general prevalence of bidirectional counterfactual thought. Participants indicated the frequency of a given counterfactual thought (upward/downward) using a 7- point scale ranging from never (0) to always (6). The ACTS contains two 5-item subscales, each coded to assess a single direction of counterfactual thought (upward/downward).

Subscale results are summed individually to examine directional tendency (upward/downward). Subsequently, the total score of ACTS items is assessed as an indication of overall counterfactual frequency. Questions are structured without reference to an eliciting event so as to examine general tendency of counterfactual thinking in everyday life. Psychometric analysis and the resulting nomological network of the ACTS indicate that the measure was predictably associated with other measures (Branch et al., manuscript in preparation).

Affective State

We administered the International Positive and Negative Affect Schedule Short Form (I-PANAS-SF; Thompson, 2007) to assess transient affective state. Participants were presented with a 10-item Likert-style measure with a 6-point response scale ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (always). Participants indicate frequency of positive and negative affective states within the last week. The I-PANAS-SF has 5-items coded to assess prevalence of negative affective states (e.g., “How often over the past week have you felt hostile?”), and 5-items coded to measure prevalence of positive affective states (e.g., “How often over the past week have you felt inspired?). Positive and negative affect subscales are calculated separately to produce a score for each measure (score range: 0- 25).

Depression, Anxiety, and Stress

The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21; Henry & Crawford, 2005) is a non-clinical Likert-style measure used to assess the presence, severity, and likelihood of developing three psychopathological conditions: depression (“I couldn’t seem to experience any positive feeling at all”), anxiety (“I was worried about situations in which I might panic and make a fool of myself”), and stress (“I found it hard to wind down”). The DASS-21 differentiates key features of depression (e.g., hopelessness, dysphoria, devaluation of life, self-deprecation, lack of interest / involvement, anhedonia and inertia), anxiety (e.g., situational anxiety, autonomic arousal, skeletal muscle effects, and subjective experience of anxious affect), and stress (e.g., difficulty relaxing, nervous arousal, and being easily upset / agitated, irritable / over-reactive and impatient), isolating the intended measures by excluding comorbid features present in other commonly used scales (e.g., weight loss, insomnia).

The DASS-21 consists of 3 subscales, with each subscale containing 7-items. Respondents rate each item on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“did not apply to me at all”) to 3 (“applied to me very much or most of the time”), based on their experiences over the past week. The total score for each subscale is calculated by summing the responses. Assessments indicated sufficient internal reliability (α =.93 for the Total scale, .88 for Depression scale, .82 for the Anxiety scale, .90 for the Stress scale; Henry & Crawford, 2005).

Rumination

The 22-item Ruminative Responses Scale (RRS; Treynor, 2003) evaluates participants’ tendency towards ruminative thought. This scale consists of 3-subscales that measure brooding (e.g., “Think about a recent situation and how it could have gone better”), reflection (e.g., “Go away by yourself and think about how you feel”), and depression-related (e.g., “Think about how alone you feel”) ruminative subfactors. Subscales vary in assessment of affective valence associated with a particular ruminative thought (brooding = unstable/anxious, reflective = neutral, depression-related = negative). The number of items differs between the depression-related (12-items), brooding (5-items), and reflection (5-items) subscales. Item response possibilities range from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). Participants were not instructed to constrain responses to a given time scale (e.g., today, this week), merely to indicate a general tendency to engage in ruminative thinking. Scores for each subscale are derived by summing the relevant items, with higher subscale scores indicating a stronger tendency to engage in that specific type of rumination. An overall total score for the RRS is calculated by summing all 22 item responses, with higher total scores reflecting a greater general tendency to ruminate.

RESULTS

Descriptives of CFT, Depression, Anxiety, Stress, Rumination, and Affect

An initial descriptive analysis was conducted to assess normality and the presence of outliers. Outliers were identified using the Interquartile Range (IQR) method, which revealed no outliers. Multiple Shapiro-Wilk Tests revealed sufficiently normal distributions for most variables. Significant positive skews were observed in DASS Depression (skewness= .94), DASS Anxiety (skewness = .76), and PANAS Negative Affect (skewness = .99). To meet the assumption of normality needed to conduct further analysis, these variables were transformed to approximate a normal distribution. DASS Depression and Anxiety underwent a square root transformation. In order to correct for the heavily skewed PANAS Negative Affect distribution, a logarithmic transformation was used. Transformation of these variables was successful in achieving approximate normality (skewness values ranging from -.36 to .3). Confirmation of linearity and homoscedasticity, and presence of confounding outliers were also assessed and were found to be unproblematic.

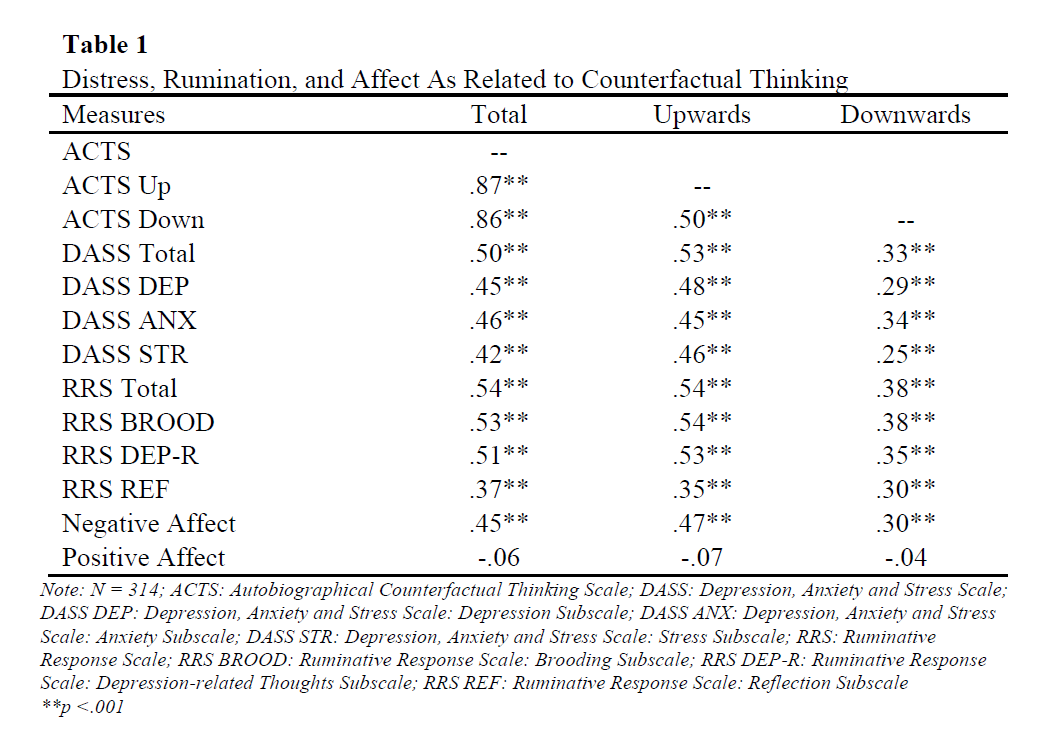

Zero-order Correlational Results

Zero-order Pearson’s r correlations were computed to assess the relations of counterfactual thinking directionality and frequency with all included predictors (Table 1). A Bonferroni correction was applied to control for familywise error, adjusting the significance threshold for each correlation test to α = 0.0017 based on 33 comparisons. The results aligned with hypothesized predictions, demonstrating consistent relationships between counterfactual thinking and psychological distress, rumination, and negative affect. All variables showed significant positive correlations with both upward and downward counterfactual thinking, except Positive Affect which was not significantly correlated with any measure of counterfactual thinking (Table 1).

Measures of rumination (e.g., brooding, reflection, depression-related thoughts), showed the strongest associations with both upward counterfactual thinking (r = 0.35 to 0.54, p < .001) and downward counterfactual thinking (r = 0.25 to 0.38, p < .001), with brooding displaying the highest correlation among all variables. Distress measures (e.g., square root of depression, square root of anxiety, and stress) were also found to associate with upward counterfactual thinking (r = 0.45 to 0.48, p < .001) and downward counterfactual thinking (r = 0.25 to 0.34, p > .001). Likewise, negative affect was correlated with upward (r = 0.47) and downward counterfactual thinking (r = 0.3).

Positive affect was found not to be significantly correlated with either upward or downward counterfactual thinking and so was not included in further analysis. To account for the smaller than anticipated sample size, a post hoc power analysis using G*Power (Faul et al., 2009). Results showed the collected sample size (N = 314) provided sufficient power (93%) to detect medium-sized correlations (r ≥ .25, α = .0017). Correlations smaller than this threshold may not have been reliably detected.

Note: N = 314; ACTS: Autobiographical Counterfactual Thinking Scale; DASS: Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale; DASS DEP: Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale: Depression Subscale; DASS ANX: Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale: Anxiety Subscale; DASS STR: Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale: Stress Subscale; RRS: Ruminative Response Scale; RRS BROOD: Ruminative Response Scale: Brooding Subscale; RRS DEP-R: Ruminative Response Scale: Depression-related Thoughts Subscale; RRS REF: Ruminative Response Scale: Reflection Subscale **p <.001

Exploratory Regression Analyses of Counterfactual Thinking Predictors

Considering observed zero-order correlations adhered to original hypotheses, further exploratory analyses were conducted to examine potential predictive power of independent factors on counterfactual thought. To this end, three linear regressions were conducted, including all variables barring positive affect. A preliminary multivariate multiple regression was first conducted to examine how the set of predictors simultaneously accounted for variance in both upward and downward counterfactual thoughts. The multivariate tests for the intercept revealed no significant effects, with all tests indicating that the model without predictors did not explain significant variance in the dependent variables (Pillai’s Trace = 0.000, Wilks’ Lambda = 1.000, Hotelling’s Trace = 0.000, Roy’s Largest Root = 0.000; all p-values = 1.000).

Examination of overall effect of predictors on total counterfactual thinking frequency scores ( R2 = .33, p < ,001) revealed Brooding (β = .28, p = 0.001; η2 = 0.044), Depression-related Thoughts (β = .22, p = 0.018; η2 = 0.026), and Anxiety (β = .16, p = 0.035; η2 =0.022) to be the most significant predictors included in the model. However, Brooding emerged as the only predictor with a moderate effect size. No significant effects were found for the other predictors, as indicated by non-significant test statistics.

Assessment of individual contribution of each predictor to upwards counterfactual thought revealed the overall model to be significant, (R2 = .36, p < .001). Among the predictors, Brooding had the strongest effect (β = .28, p < .001). Counter to expectations, anxiety and negative affect did not significantly predict upward counterfactual thinking (β = .05, p = 0.339 and β = .08, p = 0.129, respectively). Post hoc power analysis of the uCFT regression model showed the sample was sufficiently powered (91%) to detect the reported effect size (f ² = 0.575, α = .025).

The model produced to examine predictor contribution for downwards counterfactual thought was also significant (R2 = .24, p < .001). However, only Brooding (β = .23 p = 0.014) and Anxiety (β = .21, p = 0.01) showed a significant effect. A post hoc power analysis was conducted using G*Power (Faul et al., 2009) to determine whether the regression model predicting dCFT was sufficiently powered. The observed effect size was f² = .22, corresponding to a partial η² = .18 (as obtained from the omnibus F-test). With α set at .025, the analysis revealed that the model had an observed power of .90, indicating excellent sensitivity to detect the effect.

These findings reveal rumination, particularly brooding and depression-related thoughts, as the primary predictor of general counterfactual thinking. Despite initial expectations informed by correlational results, psychological distress and negative affect were not significant predictors when rumination was included in the models.

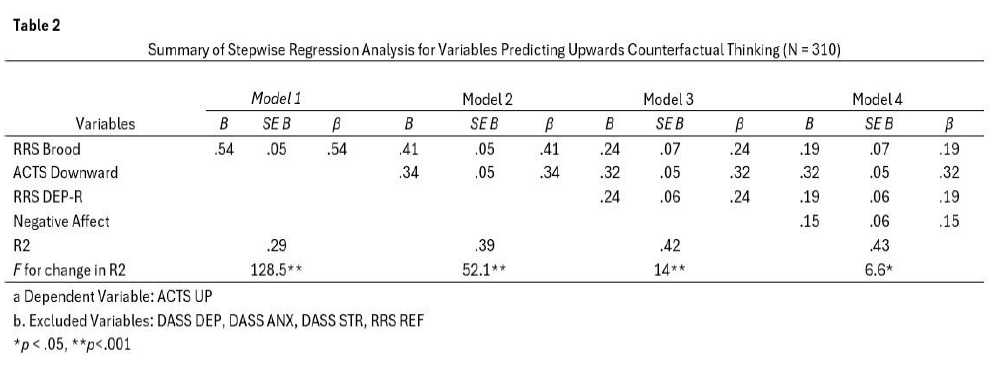

Stepwise Regression Analysis for Upward Counterfactual Thought

Stepwise regression analysis was used to identify the most robust predictors of upward counterfactual thinking by systematically evaluating all variables in the model, including those that may not contribute uniquely to the outcome. This approach allowed us to exclude variables that were statistically deemed non-contributory while still accounting for their potential shared variance with other predictors. Negative affect as well as each individual sub-measure of the DASS (depression, anxiety, and stress) and the RRS (brooding, reflection, depression-related thoughts) were included in this regression. Downward counterfactual thinking was included as an predictor to control for shared variance with upward counterfactual thought. Once again, positive affect was not included as a potential predictor.

In Model 1, brooding was the only predictor included and produced a significant model (Table 2). Model 2 introduced one additional predictor – downward counterfactual thinking. The resulting model was found to improve the model fit significantly (Table 2). After inclusion of downward counterfactual thinking, brooding remained a significant predictor, though its coefficient decreased (Table 2). Model 3 added depression-related thoughts, further improving the model fit. Depression-related thoughts were also a significant predictor of upward counterfactual thinking. Brooding and downward counterfactual thinking remained significant predictors, with slightly reduced coefficients.

In the final model (Model 4), log-transformed negative affect was included. This led to a small but significant improvement in model fit. Negative affect was a significant predictor of upward counterfactual thinking, although its contribution was smaller compared to brooding and downward counterfactual thinking. Brooding and downward counterfactual thinking continued to show significant relationships with upward counterfactual thinking. The final model iteration produced accounted for 43% of the observed variance of upward counterfactual thinking scores (R2 = .43, p < .01).

The relative contributions of the predictor variables were evaluated using standardized beta coefficients. Brooding, downwards counterfactual thoughts, depression-related thoughts and negative affect emerged as the strongest and only statistically significant predictors. Contrary to the findings of previous literature, measures of distress (depression, anxiety, stress) were not found to be significant predictors of upwards counterfactual thought. Multicollinearity diagnostics indicated no significant concerns, with Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values remaining below 4 for all predictors (RRS: Brooding = 2.45, Downwards counterfactual thought = 1.19, RRS: depression-related thoughts = 2.44, negative affect = 1.77). Reflection and all DASS sub- measures were excluded from the model on the basis of their low beta-coefficients and non-significance.

The post hoc power analysis using G*Power (Faul et al., 2009) was conducted for the final stepwise regression model (Model 4) predicting upward counterfactual thinking. The model included four predictors and yielded an R² of .43, corresponding to a large effect size (f² = .75). With an alpha level of .05 and a sample size of N = 314, the analysis indicated excellent power to detect the observed effect (1 – β = 0.94).

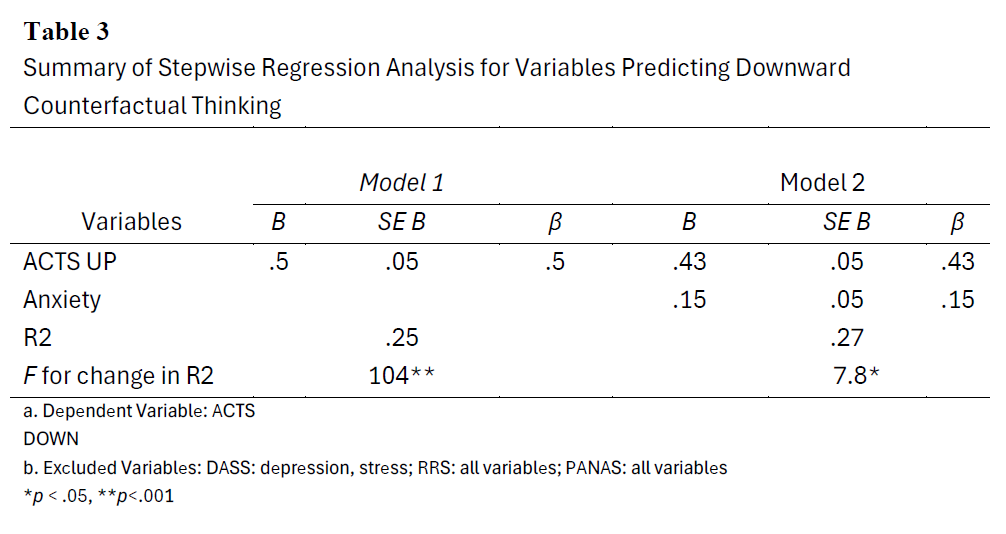

Stepwise Regression Analysis for Downward Counterfactual Thinking

A stepwise regression analysis was conducted to examine the predictors of downward counterfactual thinking. All variables were included for statistical selection via stepwise regression. Model 1 revealed a significant predictive relationship between upward counterfactual thinking and downward counterfactual thinking, accounting for 25% of the variance in downward counterfactual thinking, R² = .250 (Table 3). Model 2 (final model) added anxiety as an additional predictor, increasing the explained variance in downward counterfactual thinking to 26.8%. Both upwards counterfactual thinking (β = .433, p < .001) and anxiety (β = .151, p = .006) were significant predictors of downward counterfactual thinking. The findings suggest that while upward counterfactual thinking is a major predictor of downward counterfactual thinking, anxiety also plays a significant role, although its impact is smaller.

Excluded variables in both models, including depression, rumination, and negative affect, did not contribute significantly to the model, as indicated by their lack of statistical significance. The tolerance and variance inflation factors (VIF) for included predictors indicated no issues with multicollinearity, ensuring that the results are robust. A post hoc power analysis using G*Power (Faul et al., 2009) for the final stepwise regression model predicting dCFT (R² = .27, f² = .28) showed high power (1 – β = 0.89) with N = 314 and α = .025.

The stepwise regression analysis revealed that uCFT and anxiety were significant predictors of downward counterfactual thinking, together accounting for 26.8% of the variance. These findings suggest that while uCFT is a major contributor, anxiety also plays a smaller but significant role in accounting for the variance of dCFT scores, with other variables like depression and rumination being non-significant.

DISCUSSION

The primary aim of the present study was to investigate the relations of counterfactual thought directionality and frequency with depression, anxiety, stress, rumination, and, positive and negative mood. Participants were presented with a battery of self-report surveys in order to obtain measures of CFT, depression, anxiety, stress, rumination, and affect. We tested several hypotheses regarding the anticipated relations of the predictors and counterfactual thought tendency and directionality.

The observed correlational results served to support initial hypotheses that among individuals with increased tendency to engage in counterfactual generation, propensity to experience psychological distress (e.g., depression, anxiety, stress), rumination (e.g., brooding, reflection, depression-related thoughts), and negative affective states were higher. Expectations of upward counterfactual thoughts associations were met, showing significant positive relations to all measures of recursive negative cognitions and feelings of distress. These findings support pre-existing beliefs about the relations between upward counterfactual thinking and negative cognitive and emotional states (Davis et al., 1995; Feng et al., 2015; Gilbar et al., 2010; Markman & McMullen, 2003; Prokopčáková & Ruiselová, 2008; Roese & Olson, 1997). Also maintaining adherence to expectations, significant positive associations between downward counterfactual thinking and negative valence cognitive and emotional states were likewise observed, though these relations were weaker than the associations with upward counterfactual thought.

Relations between the included variables and counterfactual thought have been established by prior research; consequently, the observed results were not entirely surprising. Though, one must consider that prior research on counterfactual thought and psychological distress, rumination, and affect directly elicited counterfactual thoughts in reference to a specific event, not accounting for the possibility of differential associations when examined with general tendency to produce counterfactual thought in mind (Bogani et al., 2024; Feeney et al., 2005; Markman et al., 1993; McMullen, 1997; Medvic et al., 1995). However, correlational results do not indicate such differences in relations between general counterfactual thinking tendency and predictors of CFT. Rather, these results support prior conceptions of these relationships.

Given the observed relationships among included variables, exploratory regression analyses were conducted to further investigate predictors of counterfactual thinking. These analyses were not pre-registered but were undertaken to provide additional insights into the relative contributions of psychological factors beyond the original hypotheses. The following sections will synthesize insights gained from both exploratory and correlational analyses. Plausible explanations of results will be discussed based on prior literature of counterfactual functional interactions with our variables.

Counterfactual Thought and Rumination: The Primary Predictor

Hypotheses were, unfortunately, constructed without explicit reference to expected correlational strengths, beyond simply being positive or negative. As well, no rank-ordered correlational predictions were made to account for what variable would exhibit the highest correlation to uCFT/dCFT. Nevertheless, our findings indicate that among all variables, the rumination subtypes of brooding (medium effect size) and depression-related thoughts (small effect size) displayed the strongest relations to counterfactual thinking (both uCFT and dCFT). Multivariate multiple regression results revealed that brooding and depression-related thoughts were the strongest, and only consistent predictors for both uCFT and dCFT, even when accounting for psychological distress and negative affect.

Psychological distress, on the other hand, did not emerge as a significant predictor when controlled for negative ruminative subtypes. Stepwise regression analysis of uCFT also indicated brooding as the primary predictor. Brooding did not show the same predictive power in the dCFT stepwise regression analysis and was deemed an insignificant factor. These results may be due to complications in statistical procedure stemming from instability, irreproducibility and overfitting which have been found to produce unreliable and irreproducible results (Booth et al., 2021), or differences in functional interaction between psychological distress and dCFT (Parikh et al., 2022), as anxiety and uCFT emerged as the only key predictors of dCFT.

Because of its focus on specific past events, brooding, from the perspective of the Functional Theory of Counterfactual Thinking (Epstude & Roese, 2008), may closely relate to the problem- focused functionality of uCFT, wherein an individual repetitively evaluates a failure state in hopes of identification of a causal inference towards the formulation of future intent (Gilovich, 1983; Roese & Hur, 2001; Sanna & Turley, 1996). Results of prior research on repetitive negative thought processes involving persistent focus on negative emotions and their causes, correspond to the generation of counterfactual thought patterns, particularly uCFT (Davis et al., 1995; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1993; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2000; Roese & Epstude, 2017). Ruminative thoughts, typically suppressed via conscious distraction (Martin, Tesser, & McIntosh, 1993), when allowed to persist induce recursive focus on negative emotion. This recursive fixation has been found to sustain negative affect and self-critical thinking, contributing to emotional distress (Allaert et al., 2021; Broomhall & Phillips, 2018; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008; Roese et al., 2008). These results suggest that the relationship between uCFT and distress is likely mediated by negative rumination.

Conclusions about dCFT and measures of rumination are less obvious. Mentioned prior, negative rumination style was found to be a significant predictor in the multivariate multiple regression analysis, when both uCFT and dCFT were included as outcome variables. The same results were not found in the stepwise regression conducted using dCFT as the only outcome variable, however. Given the aforementioned shortcomings of stepwise regression, we are inclined to lend credence to multivariate results. Propositions on functional interactions of uCFT and negative rumination styles will be discussed in the upcoming paragraphs with multivariate regression results in mind.

Downward counterfactual thinking, as an affective regulatory mechanism (Roese, 1997), may be generated to suppress or mitigate negative affect that arises from recursive negative cognitions. If effective, this regulation may help explain why rumination robustly predicts the frequency of dCFT. In other words, individuals who engage in dCFT might be attempting to restore emotional equilibrium by imagining how situations could have been worse, thereby dampening distress and reducing the cognitive momentum typically associated with rumination. This perspective aligns with Martin and Tesser’s (1996) argument that affect does not directly evoke rumination; rather, rumination is more likely to emerge when an unresolved goal or discrepancy remains salient. Accordingly, when dCFT successfully regulates negative affect or helps reconcile perceived goal discrepancies, the cognitive conditions that usually foster rumination may be attenuated. This suggests a potentially protective or interruptive function of dCFT in the broader context of affective and cognitive regulation.

Reciprocal Production of Upward and Downward Counterfactual Thought

In both the uCFT and dCFT stepwise regression analyses, the covariate counterfactual variable emerged as a significant predictor. For instance, uCFT was a key predictor of dCFT, and dCFT was a key predictor of uCFT. This predictive relationship between upward and downward counterfactual thinking is consistent with prior evidence that once counterfactual thought is produced, regardless of direction, the chance of producing another counterfactual thought in the opposite direction increases (Markman et al., 2003).

According to previous literature, individuals who frequently engage in upward counterfactual thinking may be more prone to experiencing negative affect (Markman et al., 1993), which could, in turn, trigger downward counterfactual thoughts as a defensive mechanism to reduce emotional discomfort (for review see Roese & Epstude, 2017). This aligns with findings from previous research that downward counterfactual thinking can serve a protective function, allowing individuals to mitigate distress by focusing on “worse” outcomes than the actual past (Roese, 1997). The strong relationship between upward and downward counterfactual thought supports the notion that these thought processes are interconnected rather than independent constructs (Byrne, 2016). Whether this relationship is fundamentally tied to the varied functionality of uCFT/dCFT, or an underlying factor is outside the scope of this study.

Counterfactual Thinking and Psychological Distress

Unexpectedly, psychological distress—comprising depression, anxiety, and stress—was not a significant unique predictor of upward counterfactual thinking. While these factors demonstrated moderate correlations with counterfactual thought, they did not uniquely contribute to its variance in regression models. This suggests that while distress may be associated with uCFT, it may not be a primary driver when rumination is accounted for. These results diverge from prior studies that have emphasized a strong link between psychological distress and uCFT, though none of these studies controlled for measures of rumination (Broomhall et al., 2017; Feng et al., 2015; Markman & Miller, 2006).

While psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, and stress, was not found to significantly predict uCFT, anxiety emerged as a noteworthy predictor of downward counterfactual thinking (dCFT), albeit to a smaller degree compared to other predictors, such as uCFT itself. Anxiety often involves heightened worry about potential negative outcomes and a tendency to focus on feared possibilities (Borkovec et al., 2004). The tendency to focus on the negative or on “what could have been worse” is consistent with the cognitive patterns often seen in anxiety, where individuals may ruminate on worst-case scenarios (Mathews & MacLeod, 2005). These cognitive tendencies may fuel the generation of dCFT, as a potential coping mechanism that produces a feeling of relief stemming from avoiding those worst-case scenarios (McMullen, 1997; Roese & Epstude, 2017). For individuals with higher trait anxiety, dCFT’s ability to regulate emotion and reduce negative affect is especially effective (Parikh et al., 2022).

Counterfactual Thought and Affect

Consistent with previous findings that negative affect correlates with an increase of general counterfactual thought production (Hur, 2001; Roese & Olson, 2008), both uCFT and dCFT were found to be significantly associated with negative affect. Specifically, uCFT exhibited moderate correlations with negative affect, whereas downward counterfactual thinking dCFT showed a weaker, though still significant, association with negative affect.

Despite a multitude of past literature suggesting that negative affect is the chief byproduct of uCFT, which serves to motivate behavioral change (Markman & Miller, 2006; Miller & Markman, 2007; Roese & Epstude, 2007, 2008; Roese & Olson, 1997, 2008; Sanna, 1998; Sanna, Meier, et al., 2001; Sanna et al., 1998; Sanna et al., 2006; Sanna, Turley-Ames, & Meier, 1999), and its designation as a key determinant in general counterfactual activation, our results show negative affect to be a less prominent predictor than anticipated. In both the multivariate multiple regression and the stepwise regression for dCFT, negative affect was found to be insignificant. Only in the stepwise regression for uCFT was its predictive power shown to be marginally significant.

A plausible explanation for this discrepancy may be that the general tendency to produce counterfactual thoughts is not merely determined by the presence of transient affective states; rather, negative cognitions that promote and sustain negative affect create a feedback loop reinforcing the propensity to generate counterfactuals throughout daily life. This proposition deviates from the production of discrete counterfactuals, which assess a specific situation and are typically triggered by momentary affective states.

The absence of any significant relationships between positive affect and uCFT/dCFT led to the exclusion of this variable from further analysis. Nevertheless, this result contradicts previous findings of the onset of positive affect as a byproduct of CFT via a contrast effect wherein the perceived (un)desirability of an outcome is enhanced when compared with another plausible state (Gamlin et al., 2020; Markman et al., 2008; Roese, 1994; Sanna, 2000; Sanna, Meier, et al., 2001).

Limitations and Future Directions

The present study employed a sample primarily consisting of young females, a demographic in which measures distress, rumination, and negative affect may be elevated relative to the general population (Broderick & Korteland, 2004; Fujita et al., 1991; McLean et al., 2011; Ricarte Trives et al., 2016). Additionally, Özbek et al. (2020) assessed age-differences in counterfactual thinking, identifying significant age differences in one of the two studies conducted. In the absence of an analysis of gender and age effects, the generalizability of the observed results is unknown. The analysis of depression and anxiety assessments relied entirely on sub-clinical self-report questionnaires. Resource and sampling constraints necessitating this approach aside, clinical assessment of these conditions would bolster the relational conclusions proposed in the present study.

While the present study offers valuable insights into the complex relationships between counterfactual thinking (CFT), rumination, and affective states, several avenues for future research remain. First, future studies should aim to address the limitations related to sample diversity. The current study employed a predominantly young female sample, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other demographics, such as older adults or male participants. Research expanding to a more diverse population—taking into account variables such as age, gender, and clinical status— would help determine whether the observed relationships hold across different groups. In particular, age-related differences in counterfactual production, where younger samples were found to engage in CFT more than older samples (Özbek et al., 2020), could provide a more nuanced understanding of how the developmental trajectory of counterfactual thought relates with psychological distress.

Furthermore, given the limitations of self-report measures in accurately capturing the complexities of psychological states, future studies would benefit from using more robust clinical assessments of depression, anxiety, and stress. Incorporating objective measures of these conditions— such as diagnostic interviews or physiological indicators—could enhance the reliability and precision of findings regarding the relationship between psychological distress and CFT. Longitudinal designs might also offer valuable insights into the causal directionality of these relationships, especially with regard to the impact of CFT on subsequent psychological distress and vice versa. This would address the temporal dynamics that were not fully explored in the current study.

Additionally, the role of positive affect in counterfactual thinking warrants further investigation. While positive affect was excluded from analysis in this study due to a lack of significant relations, the literature suggests that positive affect could play a role in certain counterfactual contexts (Markman et al., 2008; Sanna, 2000). Future research could explore how positive counterfactual thoughts might influence emotional regulation, particularly in relation to more adaptive coping mechanisms.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the University of Utah Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program. I would like to thank Dr. Jared Branch for his support and encouragement, as well as Dr. Lisa Aspinwall and Dr. Kristina Rand for their guidance. Thanks also to my mother and my brother for their unending love and support in my academic endeavors.

Bibliography

Allaert, J., De Raedt, R., van der Veen, F. M., Baeken, C., & Vanderhasselt, M. A. (2021). Prefrontal tDCS attenuates counterfactual thinking in female individuals prone to self-critical rumination. Scientific reports, 11(1), 11601. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-90677-7

Berntsen, D., & Rubin, D. C. (2006). The centrality of event scale: A measure of integrating a trauma into one’s identity and its relation to post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(2), 219–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.01.009

Booth, D. E., Gopalakrishna-Remani, V., Cooper, M. L., Green, F. R., & Rayman, M. P. (2021).

Boosting and lassoing new prostate cancer SNP risk factors and their connection to selenium. Scientific reports, 11(1), 17877. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-97412-2

Broderick, P. C., & Korteland, C. (2004). A Prospective Study of Rumination and Depression in Early Adolescence. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 9(3), 383– 394. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104504043920

Branch, J. G. (2023). Individual differences in the frequency of voluntary & involuntary episodic memories, future thoughts, and counterfactual thoughts. Psychological Research, 87, 2171– 2182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-023-01802-2

Branch, J.G., Horgos, P., & Westring, C. (Manuscript in preparation). The Development and Validation of The Autobiographical Counterfactual Thinking Scale (ACTS).

Broomhall, A. G., Phillips, W. J., & Esposito, C. (2017). Upward counterfactual thinking and depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 55, 56–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.04.010

Broomhall, A. G., & Phillips, W. J. (2018). “Self-referent upward counterfactuals and depression: Examining regret as a mediator”: Erratum. Cogent Psychology, 5(1), Article 1440996. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2018.1440996

Bogani, A., Tentori, K., Ferrante, D., & Pighin, S. (2024). Counterfactual thoughts in complex causal domain: Content, benefits, and implications for their function. Thinking & Reasoning, 30(4), 612–647. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546783.2024.2343455

Boninger, D. S., Gleicher, F., & Strathman, A. (1994). Counterfactual thinking: From what might have been to what may be. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(2), 297–307. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.2.297

Borkovec, T. D., Alcaine, O. M., & Behar, E. (2004). Avoidance Theory of Worry and Generalized Anxiety Disorder. In R. G. Heimberg, C. L. Turk, & D. S. Mennin (Eds.), Generalized anxiety disorder: Advances in research and practice (pp. 77–108). The Guilford Press.

Byrne R. M. (2016). Counterfactual Thought. Annual review of psychology, 67, 135–157. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033249

Callander, G., Brown, G. P., Tata, P., & Regan, L. (2007). Counterfactual thinking and psychological distress following recurrent miscarriage. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 25(1), 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646830601117241

Davis, C. G., Lehman, D. R., Wortman, C. B., Silver, R. C., & Thompson, S. C. (1995). The Undoing of Traumatic Life Events. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(2), 109- 124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167295212002

Epstude, K., & Roese, N. J. (2007). Beyond rationality: Counterfactual thinking and behavior regulation. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 30(5-6), 457– 458. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X07002634

Epstude, K., & Roese, N. J. (2008). The functional theory of counterfactual thinking. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 12(2), 168–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868308316091

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior research methods, 41(4), 1149– 1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Feng, X., Gu, R., Liang, F., Broster, L. S., Liu, Y., Zhang, D., & Luo, Y. (2015). Depressive states amplify both upward and downward counterfactual thinking. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 97(2), 93-98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2015.04.016

Feeney, A., Gardiner, D. R., Johnston, K., Jones, E., & McEvoy, R. J. (2005). Is Regret for Inaction Relatively Self-enhancing? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 19(6), 761–777. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1113

Fujita, F., Diener, E., & Sandvik, E. (1991). Gender differences in negative affect and well-being: the case for emotional intensity. Journal of personality and social psychology, 61(3), 427–434. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.61.3.427

Gamlin, J., Smallman, R., Epstude, K., & Roese, N. J. (2020). Dispositional optimism weakly predicts upward, rather than downward, counterfactual thinking: A prospective correlational study using episodic recall. PLoS ONE, 15(8), Article e0237644. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237644

Gavanski, I., & Wells, G. L. (1989). Counterfactual processing of normal and exceptional events. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 25(4), 314–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(89)90025-5

Gilbar, O., Plivazky, N., & Gil, S. (2010). Counterfactual thinking, coping strategies, and coping resources as predictors of PTSD diagnosed in physically injured victims of terror attacks. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 15(4), 304–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325020903382350

Gilovich, T., Wang, R. F., Regan, D., & Nishina, S. (2003). Regrets Of Action and Inaction Across Cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 34(1), 61-71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022102239155

Gleicher, F., Kost, K. A., Baker, S. M., Strathman, A. J., Richman, S. A., & Sherman, S. J. (1990). The role of counterfactual thinking in judgments of affect. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 16(2), 284–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167290162009

Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. The British journal of clinical psychology, 44(Pt 2), 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466505X29657

Jeong, D., Aggarwal, S., Robinson, J., Kumar, N., Spearot, A. C., & Park, D. S. (2022). Exhaustive or exhausting? Evidence on respondent fatigue in long surveys. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4013423

Kahneman, D., & Miller, D. T. (1986). Norm theory: Comparing reality to its alternatives. Psychological Review, 93(2), 136–153. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.93.2.136

Landman, J. (1987). Regret: A theoretical and conceptual analysis. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 17(2), 135–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.1987.tb00092.x

Lieberman, M. D., Gaunt, R., Gilbert, D. T., & Trope, Y. (2002). Reflexion and reflection: A social cognitive neuroscience approach to attributional inference. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology, Vol. 34, pp. 199–249). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(02)80006-5

Liu, L. G. (1985). Reasoning counterfactually in Chinese: Are there any obstacles? Cognition, 21(3), 239–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0277(85)90026-5

Markman, K. D., Gavanski, I., Sherman, S. J., & McMullen, M. N. (1993). The mental simulation of better and worse possible worlds. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 29(1), 87–109. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.1993.1005

Markman, K. D., & McMullen, M. N. (2003). A reflection and evaluation model of comparative thinking. Personality and social psychology review : an official journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc, 7(3), 244–267. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0703_04

Markman, K. D., & Miller, A. K. (2006). Depression, control, and counterfactual thinking: Functional for whom? Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 25(2), 210–227. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2006.25.2.210

Markman, K. D., McMullen, M. N., & Elizaga, R. A. (2008). Counterfactual thinking, persistence, and performance: A test of the reflection and evaluation model. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(2), 421–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2007.01.001

Martin, L. L., Tesser, A., & McIntosh, W. D. (1993). Wanting but not having: The effects of unattained goals on thoughts and feelings. In D. M. Wegner & J. W. Pennebaker (Eds.), Handbook of mental control (pp. 552–572). Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Martin, L. L., & Tesser, A. (1996). Some ruminative thoughts. In R. S. Wyer, Jr. (Ed.), Ruminative thoughts (pp. 1–47). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Mathews, A., & MacLeod, C. (2005). Cognitive vulnerability to emotional disorders. Annual review of clinical psychology, 1, 167–195. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143916

McLean, C. P., Asnaani, A., Litz, B. T., & Hofmann, S. G. (2011). Gender differences in anxiety disorders: prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. Journal of psychiatric research, 45(8), 1027–1035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.006

Medvec, V. H., Madey, S. F., & Gilovich, T. (1995). When less is more: counterfactual thinking and satisfaction among Olympic medalists. Journal of personality and social psychology, 9(4), 603–610. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.69.4.603

Miller, D. T., & Gunasegaram, S. (1990). Temporal order and the perceived mutability of events: Implications for blame assignment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(6), 1111–1118. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.59.6.1111

Miller, D. T., Turnbull, W., & McFarland, C. (1989). When a coincidence is suspicious: The role of mental simulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(4), 581–589. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.4.581

Miller, D. T., & McFarland, C. (1986). Counterfactual thinking and victim compensation: A test of norm theory. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 12(4), 513–519. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167286124014

Nasco, S. A., & Marsh, K. L. (1999). Gaining control through counterfactual thinking. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(5), 556–568. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167299025005002

Niedenthal, P. M., Tangney, J. P., & Gavanski, I. (1994). ” If only I weren’t” versus” If only I hadn’t”: Distinguishing shame and guilt in conterfactual thinking. Journal of personality and social psychology, 67(4), 585.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Morrow, J., & Fredrickson, B. L. (1993). Response styles and the duration of episodes of depressed mood. Journal of abnormal psychology, 102(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.20

Nolen-Hoeksema S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of abnormal psychology, 109(3), 504–511.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking Rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400-424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088

Özbek, M., Bohn, A., & Berntsen, D. (2020). Characteristics of personally important episodic memories, counterfactual thoughts, and future projections across age and culture. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 34, 1020-1033.

Parikh, N., De Brigard, F., & LaBar, K. S. (2022). The Efficacy of Downward Counterfactual Thinking for Regulating Emotional Memories in Anxious Individuals. Frontiers in psychology, 12, 712066. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.712066

Prokopčáková, A., & Ruiselová, Z. (2008). Counterfactual thinking as related to anxiety and self- esteem. Studia Psychologica, 50(4), 429–435.

Ricarte Trives, J. J., Bravo, B. N., Postigo, J. M. L., Ros Segura, L., & Watkins, E. (2016). Age and gender differences in emotion regulation strategies: Autobiographical memory, rumination, problem solving and distraction. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 19, Article E43. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2016.46

Roese, N. J. (1997). Counterfactual thinking. Psychological Bulletin, 121(1), 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.133

Roese, N. J., & Olson, J. M. (1993). The structure of counterfactual thought. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 19(3), 312–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167293193008

Roese, N. J., Hur, T., & Pennington, G. L. (1999). Counterfactual thinking and regulatory focus: Implications for action versus inaction and sufficiency versus necessity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1109–1120. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1109

Roese, N. J., & Olson, J. M. (1997). Counterfactual thinking: The intersection of affect and function. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology, Vol. 29, pp. 1–59). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60015-5

Roese, N. J., & Hur, T. (1997). Affective determinants of counterfactual thinking. Social Cognition, 15(4), 274–290. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.1997.15.4.274

Roese, N. J., & Olson, J. M. (1995). Functions of counterfactual thinking. In N. J. Roese & J. M. Olson (Eds.), What might have been: The social psychology of counterfactual thinking (pp. 169–197). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Roese, N. J., & Epstude, K. (2017). The functional theory of counterfactual thinking: New evidence, new challenges, new insights. In J. M. Olson (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 1–79). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aesp.2017.02.001

Roese, N. J., Epstude, K., Fessel, F., Morrison, M., Smallman, R., Summerville, A., & Segerstrom, S. (2009). Repetitive regret, depression, and anxiety: Findings from a nationally representative survey. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 28(6), 671–688. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2009.28.6.671

Roese, N. J. (1994). The functional basis of counterfactual thinking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(5), 805–818. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.66.5.805

Rubin, D. C., Berntsen, D., & Bohni, M. K. (2008). A memory-based model of posttraumatic stress disorder: evaluating basic assumptions underlying the PTSD diagnosis. Psychological review, 115(4), 985–1011. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013397

Rye, M. S., Cahoon, M. B., Ali, R. S., & Daftary, T. (2008). Counterfactual Thinking for Negative Events Scale (CTNES) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t01591-000

Sanna, L. J., Meier, S., & Wegner, E. A. (2001). Counterfactuals and motivation: Mood as input to affective enjoyment and preparation. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(2), 235–256. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466601164830

Sanna, Lawrence & Parks, Craig & Meier, Susanne & Chang, Edward & Kassin, Briana & Lechter, Joshua & Turley-Ames, Kandi & Miyake, Tina. (2003). A Game of Inches: Spontaneous Use of Counterfactuals by Broadcasters During Major League Baseball Playoffs1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 33. 455 – 475. 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2003.tb01906.x.

Sanna, L. J., Chang, E. C., & Meier, S. (2001). Counterfactual thinking and self-motives. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(8), 1023–1034. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167201278009

Sanna, L. J., & Turley, K. J. (1996). Antecedents to spontaneous counterfactual thinking: Effects of expectancy violation and outcome valence. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(9), 906–919. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167296229005

Sanna, L. J. (1998). Defensive pessimism and optimism: The bitter-sweet influence of mood on performance and prefactual and counterfactual thinking. Cognition and Emotion, 12(5), 635– 665. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999398379484

Sanna, L. J., Turley, K. J., & Mark, M. M. (1996). Expected evaluation, goals, and performance: Mood as input. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(4), 323–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167296224001

Schwarz, N. (1990). Feelings as information: Informational and motivational functions of affective states. In E. T. Higgins & R. M. Sorrentino (Eds.), Handbook of motivation and cognition: Foundations of social behavior, Vol. 2, pp. 527–561). The Guilford Press.

Sherman, S. J., & McConnell, A. R. (1995). Dysfunctional implications of counterfactual thinking: When alternatives to reality fail us. In N. J. Roese & J. M. Olson (Eds.), What might have been: The social psychology of counterfactual thinking (pp. 199–231). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Treynor, W., Gonzalez, R., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2003). Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27(3), 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023910315561

Turley, K. J., Sanna, L. J., & Reiter, R. L. (1995). Counterfactual thinking and perceptions of rape. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 17(3), 285–303. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp1703_1

Zeelenberg, M., & Pieters, R. (2007). A theory of regret regulation 1.0. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327663jcp1701_3

APPENDIX

Autobiographical Counterfactual Thinking Scale (ACTS)

We all think about how events in our life could have been different from reality. Sometimes these are important events and other times they are simple, everyday events. When we imagine how personal events could have played out differently, we sometimes imagine how they could have been worse, and other times how they could have been better. Using the following scale, rate how often you experience each item.

0 = Never; 1 = Almost never; 2 = Rarely; 3 = Sometimes; 4 = Often; 5 = Almost always; 6 = Always

Downward Items

- When I am feeling sad, I think back on past events in my life and imagine how they could have been worse.

- When my mind wanders, I think about how my past could have been worse.

- I find myself imagining how major events in my life could have been worse.

- I find myself thinking about my past and how it could have been worse

- I replay important events from my past and imagine how different my life would be if they had gone worse.

Upward Items

- I think about personal events and how they could have been better.

- When I reflect on my life, I find myself thinking about how my life could have been better.

- When my mind wanders, I think about how my past could have been better.

- I find myself imagining how major events in my life could have been better.

- I find myself thinking about my past and how it could have been better.

Full Autobiographical Counterfactual Thinking Scale (ACTS) [[in order]]

- I find myself thinking about my past and how it could have been better.

- When I am feeling sad, I think back on past events in my life and imagine how they could have been worse.

- When my mind wanders, I think about how my past could have been better.

- I find myself imagining how major events in my life could have been better.

- I find myself thinking about my past and how it could have been worse

- I think about personal events and how they could have been better.

- I replay important events from my past and imagine how different my life would be if they had gone worse.

- When my mind wanders, I think about how my past could have been worse.

- When I reflect on my life, I find myself thinking about how my life could have been better.

- I find myself imagining how major events in my life could have been worse.

Media Attributions

- Capture

- Capture

- Capture