College of Social and Behavioral Science

124 Improving Law Enforcement’s Response Towards Victims of Sexual Violence: The Impact of Traumatic Memory

Naomi Hill

Faculty Mentor: Heather Melton (Criminology, University of Utah)

Abstract

Memory plays a pivotal role in the criminal justice system, serving as a crucial component of evidence in numerous criminal proceedings, particularly those reliant on witness accounts, like sexually violent acts. Unfortunately, victims of sexual assault and rape often face disbelief when their memories come into question. Upon delving deeper into the existing research on traumatic memory, it becomes evident that law enforcement has misinterpreted signs of trauma, wrongly perceiving them as indicators of dishonesty among victims and dismissing their cases. However, the recent introduction of trauma- informed policing in Utah Police Departments may help police understanding and response to traumatic memory.

The present study is an exploration of the perspectives and experiences of law enforcement within the Salt Lake Valley. Investigating the narrative accounts of law enforcement might enhance a deeper understanding of whether this new approach has resulted in tangible changes in policing methods and law enforcement perceptions. This inquiry aims to uncover the valuable insights and experiences that contribute to the ongoing dialogue about the effectiveness and impact of trauma-informed policing. The study interviewed three current or former detectives who have received trauma-informed training. The findings reveal that officers who have undergone this training report perceiving lower rates of false reports among victims and demonstrate a clear understanding of how trauma and traumatic memory affect victims. The detectives involved in the study noted improved victim engagement and an increased sense of empathy and understanding toward victims. Ultimately, this research supports the case for broader adoption of trauma-informed training across the United States.

Improving Law Enforcement’s Response Towards Victims of Sexual Violence: The Impact of Traumatic Memory

Memory plays a pivotal role in the criminal justice system, serving as a crucial component of evidence in numerous criminal proceedings, particularly those reliant on a witness’s account, like sexually violent acts. Unfortunately, victims of sexual assault and rape often face disbelief when their memories come into question. With only approximately 12 to 40% of victims coming forward, sexual assault is the most underreported violent crime (Rich, 2016). Furthermore, an even smaller percentage of reported cases, roughly 12.5%, reach prosecution (Westera et al., 2016).

This disproportionate number might be attributed to police not referring the case to prosecution. The first interaction between law enforcement and sexual assault victims is critical because officers have the unique ability to decide if a case should be referred to prosecution. In a study done by Dr. Rebecca Campbell, 86% of sexual assault cases reported to the police did not go further than this interaction (National Institute of Justice, 2019). Other studies suggest that 50 to 75% of cases never reach prosecution (Rich, 2019). This may partially be explained by the fact that victim testimony is frequently not believed. Existing research on traumatic memory suggests law enforcement has misinterpreted signs of trauma, wrongly perceiving the signs as indicators of dishonesty among victims and dismissing their cases.

With the recent introduction of trauma-informed policing in select cities and states across the United States, including Utah Police Departments, there is a valuable opportunity to examine the tangible effects of this evolving approach on victims of crime. This exploration aims to find common themes through interviews with law enforcement officers from departments in the Salt Lake Valley, seeking insights into the impact this innovative policing strategy has had on law enforcement practices and perceptions. Through these interviews, the goal was to gain a deeper understanding of how trauma-informed policing has brought about genuine changes in the field. Specifically, the focus will be on exploring the law enforcement officers’ experiences when dealing with rape and sexual assault victims, the nature of their training programs, and their comprehension of traumatic memory. This inquiry seeks to uncover valuable perspectives and experiences that contribute to the ongoing conversation about the effectiveness and implications of trauma-informed policing.

Literature Review

Traumatic Memory

To better understand traumatic memories, it’s essential to first explore how memory systems function. Memory refers to the systems and processes responsible for storing and retrieving information. The hippocampus, amygdala, cerebellum, and prefrontal cortex are key areas of the brain involved in memory recollection (Payne, 2023). The hippocampus and amygdala are responsible for memory consolidation, stabilizing memory in the brain to be recalled. For a memory to be accurately recalled, it must undergo encoding (organizing sensory information), storage (retaining information), and retrieval (accessing the memory) processes (Payne, 2023). The amygdala processes sensory and emotional memories (National Institute of Justice, 2019). Factors such as high emotional response can significantly impact memories.

Trauma and Recovery by Judith Herman in 1992 was one of the first works to define traumatic memory. Her work explains that traumatic memories are encoded in a manner that deviates from the typical pattern of memory, often manifesting as fragmented, emotionally charged, and disorganized experiences (Herman, 1992). Unlike regularly encoded memories, traumatic memories may lack linearity and verbal coherence, characterized instead by “vivid sensations and images” (Herman, 1992, p.38). This variation in encoding between regularly encoded and traumatic memories contributes to the diverse ways individuals may recall a traumatic experience, if at all. Herman (1992) explains that victims may recollect with “intense emotion without clear memory of the event, or [they] may remember everything in detail but without emotion” ( p. 35). Because traumatic memories are uniquely encoded, it is not unreasonable to conclude that the crucial details of a case, such as the appearance of a perpetrator or specific elements of the crime, may easily be lost.

Many psychologists and sociologists like Dr. Rebecca Campbell has built upon Herman’s work. Dr. Campbell’s work has provided further insight into victim behavior by explaining the neurological functions of traumatic memories. She provides insights into the neurobiology of traumatic memories. Traumatic memories occur because the hippocampus and amygdala are impacted by fluctuations in hormones (such as catecholamines, cortisol, opioids, and oxytocin) that are released during the trauma (National Institute of Justice, 2019). When a victim is sexually assaulted, their memory recall can be impacted because of an increase in catecholamines, which “impair the circuits in our brain that control rational thought” (National Institute of Justice, 2019). This impairment, coupled with the multifaceted effects on memory consolidation, results in a highly unpredictable recollection of a victim’s traumatic experience. When memory systems are flooded with hormones, memories become fragmented and disorganized (National Institute of Justice, 2019).

Memories recalled by victims during testimony about a traumatic experience can vary greatly and often occur slowly due to the way the brain is affected by trauma. Recalling these memories can be both emotionally painful and physically difficult, requiring significant time and energy from the victim to ensure accuracy (National Institute of Justice, 2019). Although traumatic memories differ from typically encoded memories in terms of their characteristics, they remain credible. As Dr. Campbell explains, while the process of storing traumatic memories may be disorganized, the retention and recall of these memories are still accurate: “The act of laying down that memory is accurate, the recall is accurate… the storage of it is disorganized” (National Institute of Justice, 2019).

Traumatic Memory and Law Enforcement

The belief that rape is often falsely reported about has been sustained and woven into the history of law enforcement. Some of the first written accounts of this assumption can be quoted from the 17th century, “Rape is a most detestable crime. … but it must be remembered that it is an accusation easily to be made, and hard to be proved, and harder to be defended by the party accused, though never so innocent”(Quinlan, 2016). Until the late 20th century, this statement was read in courtrooms by judges to the jury (Miller & Armstrong, 2015). A study as cited by Quinlan revealed that, “police were significantly less likely to believe a woman’s rape report and lay charges on the accused if she had been drinking or hitchhiking, was younger than 19 or older than 30 years of age, had no injuries from the assault, or was separated or divorced” (Quinlan, 2016).

Law enforcement currently exhibits varying comprehension of the frequency of false reports. In The Rape Investigation Handbook, there is a heavy emphasis on the notion that rape is often lied about. The author suspects that false reports of rape could be as high as 41 to 60% (Turvey & Savino, 2014). This number reflects some police perceptions as well; in a study, Ontario police had varying understandings of the prevalence of false reports. This number ranged from 5% to an excessive 50% (Quinlan, 2016). Other sources have reported police to believe 16 to 25% uncredible (Edwards et al., 2011). It’s crucial to note that the overwhelming majority of rape and sexual assault reports are truthful, with an estimated 2 to 8% identified as false (Leithead, 2022). This percentage comes from extensive research that concludes a sexual assault report is unfounded on the basis that evidence proved that no crime occurred or was attempted. This determination was only reached through a comprehensive investigation; it is not feasible to classify a case as unfounded solely based on a preliminary inquiry or initial interview with the victim (Leithead, 2022). Misinterpreting the extent of false reports is perilous. It may prompt investigators to approach interactions with victims assuming they are probably dishonest, creating a self-fulfilled prophecy. If police officers enter interactions with victims with this assumption, there is a higher likelihood they will find the case to be unfounded or push a victim to recant their statement, potentially categorizing the case as false (Rich, 2017). But why might law enforcement view victim behavior as dishonesty?

Dr. Rebecca Campbell’s theory sheds light on a crucial aspect: law enforcement personnel can misinterpret signs of trauma, such as victims’ memories, as deliberate deception. In her explanation, she emphasizes that in the context of rape and sexual assault, behaviors perceived as “evasive” or “sketchy” are not indicative of deception but rather characteristics of trauma. She notes that the training received by law enforcement personnel may lead them to associate sketchiness with dishonesty (National Institute of Justice, 2013). As cited in Dr. Campbell’s lecture, police officers have been quoted as saying, “[victims] say stuff that makes no sense” and “I see them hedge, making it up as they go along” (National Institute of Justice, 2019). The way the police in the study talk about victim behavior reveals that they do not understand the manifestations of trauma in memory.

Numerous studies investigating police responses to traumatic memories affirm that law enforcement has frequently misread these indicators. Quinlan (2016) interviewed 17 police officers in Ontario, Canada. Many police looked for signs of story inconsistency to prove that a victim was lying. The study revealed that there were varying responses from police officers when it came to handling sexually violent crimes, with multiple officers not believing victims because they expected the recall of their memories to be in vivid detail, concise, and quick (Quinlan, 2016). Many officers worry that if a victim does not recall the information in this manner, then they are making it up.

Officers in the study had varying techniques when talking to potential victims of rape. Some indicated they would determine truthfulness by looking for inconsistencies in the account (Quinlan, 2016). Manipulation tactics were also present in some police officers’ methods. Some made victims state the events of the assault in reverse chronological order and attempted to poke holes in their narrative. One officer explains that she asks questions one might not expect, like if the perpetrator was circumcised to determine truthfulness, “I’ve got a few people on that. ‘Cause they don’t know. But they already said they saw his penis, so then you throw that question and they might go white ‘cause they are going to be like ‘Holy crap I don’t know.’” (Quinlan, 2016). With the knowledge of how trauma impacts memory functions, police looking for a victim to be able to, “tell her narrative consistently forward and backward, while recounting the details of the assault and her perpetrator’s body” would not only be an inaccurate way to prove truthfulness but could retraumatize a victim (Quinlan, 2016).

The police interrogation processes in this study reveal a variation and a lack of understanding that trauma affects memory functions, which can result in victims being unable to recall memories in chronological order and experiencing gaps in their recollections. This further suggests that victims may have had their cases dismissed when they were exhibiting signs of traumatic memory.

The misinterpretation of traumatic memories becomes evident in the case of 18-year-old Marie Adler (Miller & Armstrong, 2015). Following an incident where she was raped at knife-point by a masked stranger in her apartment, she faced secondary victimization at the hands of the Lynnwood Police Department (Miller & Armstrong, 2015). Investigators, Sergeant Jeffrey Mason and Jerry Rittgarn, subjected the victim to multiple retellings of her ordeal, both in interrogations and written statements (Miller & Armstrong, 2015). Uncovering slight inconsistencies in her account, particularly regarding how she untied herself to seek help, investigators perceived these variations as discrepancies, ignoring all other evidence. Rittgarn stated, “Based on her answers and body language it was apparent that [Marie] was lying about the rape” (Miller & Armstrong, 2015). The relentless interrogation coerced Adler to start doubting her own memory and write a false confession, admitting to fabricating the reported rape. As a result, she faced charges of filing a false report, a daunting $500 fee, and ridicule/bullying from the public (Miller & Armstrong, 2015)

Adler was proven to have told the truth the whole time when a photo of her license was found in a serial rapist’s home (Miller & Armstrong, 2015). Detective Stacy Galbraith and Sergeant Edna Hendershot, two female detectives from other departments, were able to find the serial rapists by approaching other victims of his with empathy and listening to their accounts openly (Miller & Armstrong, 2015). The Lynnwood police department used integration tactics towards Alder similar to those used against people who have committed a crime, not that of a victim. They saw her signs of traumatic memory and not only disregarded her case but also charged her criminally for it. It’s also noteworthy to take into account that at the time of Marie Adler’s rape, law enforcement agencies did have protocols in place to avert the missteps witnessed in this case (Miller & Armstrong, 2015). However, these protocols failed in implementation, which poses the question: What can be done to avoid further victimization and make sure victims are handled appropriately when they come to the police?

Improvements in Police Practice

The implementation of a more trauma-informed approach to investigation might improve the interactions between victims of sexually violent acts and law enforcement. Trauma-informed policing is about creating an understanding and recognition of trauma’s impact on individuals (Lovell & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 2023). The goal of trauma-informed training is to instruct officers on the neurobiological impacts of trauma (such as traumatic memory), promote approaches to interviewing and engaging with survivors that achieve the following: prioritize the victim’s well-being, foster increased engagement with the justice system, and ultimately aid practitioners in conducting comprehensive investigations to ensure accountability for offenders (Lovell & Langhinrichsen- Rohling, 2023).

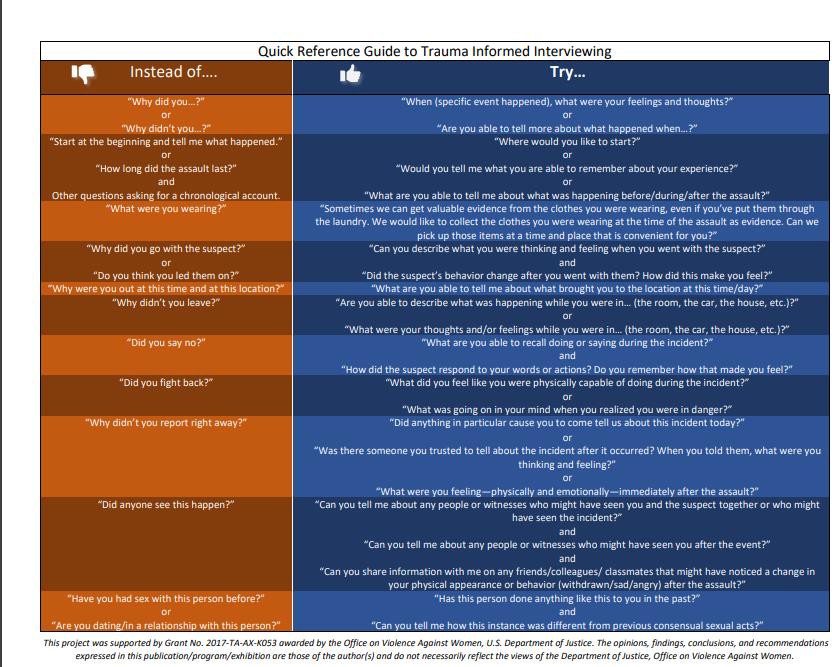

Trauma-informed policing can particularly aid in the investigations of victims exhibiting traumatic memory because it informs law enforcement to take their time with the victim and not expect memories to come in an organized and chronological fashion. The International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) created a guideline of interview questions to use toward victims of sexual assault and rape seen in Figure 1 below. Instead of asking a victim to give a chronological account of the events, law enforcement is told to ask open questions like “Where would you like to start?”(IACP, 2020). This question gives the victim the agency to explain what happened to them when their memory begins, without the pressure of trying to remember how it occurred within a timeframe. The guidelines for reframing questions not only frame questions in a manner that minimizes victim blame from a police officer, but also help aid in the victim’s memory consolidation, “Detectives who convey empathy elicit more actionable narratives from victims and are more likely to refer cases to the District Attorney for prosecution”(Rich, 2017).

Figure 1. (IACP, 2020)

In 2023, only one state and three cities had administered in-person training on trauma-informed policing (Lovell & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 2023). One particular department that has proactively instituted this form of policing is the Salt Lake City Police Department. They have put into place a four-hour training for their officers that:

covered research regarding sexual assault offenders, survivor vulnerabilities exploited by offenders, the neurobiology of trauma, rape myth acceptance, research on the small percentage of false allegations, as well as survivor interview techniques and new department policies for responding to sexual assault (Lovell & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 2023).

This training was found to be effective because it increased victims’ ongoing involvement with police (Lovell & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 2023). The trauma-informed policing implemented by the SLCPD and other departments has appeared to have positive results such as, “ improvements in police perceptions of survivors, knowledge of trauma-informed practice, and improvements in survivor engagement” (Lovell & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 2023).

The Sexual Assault Kit Processing Act, effective as of 2023, has mandated trauma-informed training for law enforcement within the state of Utah. This training includes improved interviewing techniques that recognize signs of trauma (Utah Code Section 53-10-908, 2023). The law required Utah’s law enforcement departments to develop programs focused on identifying trauma symptoms, understanding their impact, and responding with compassion and sensitivity. It also stressed the importance of providing services in a nonjudgmental manner while being aware of cultural perceptions and debunking common myths related to sexual assault.

With this knowledge of trauma-informed training being implemented in select areas within the US, it is evident that those who are victims of sexual violence may be treated vastly differently depending on the jurisdiction that handles the crime or which investigator or officer handles the case. When someone reports a sexually violent act, the variation in responses has been referred to as “playing the police lottery”(Rich, 2017). The methods employed by an investigator can vary considerably based on their investigative background and their grasp of sexual assault, trauma, and the experiences of survivors (Quinlan, 2016). The absence of standardized investigative practices leads to notable discrepancies in how law enforcement responds to reports of sexual assault, which poses the question: Why has trauma-informed policing not been widely instituted among police departments across the country?

Numerous obstacles have been identified that could hinder the continued implementation of this practice. Karen Rich explains that certain factors, such as those affecting an officer’s capacity to embrace the new practice and institutional barriers, play a role in impeding the adoption of the practice. The author explains that police are hired with certain personality types that might make it hard for them to accept this new practice. Trauma-informed policing asks for police to go against their conventional understandings of interrogation: “Police work, traditionally conceived, requires the ability to distance oneself from feelings, take control in an ambiguous situation, focus on facts rather than perceptions, and act quickly”(Rich, 2017). Other factors include,

“institutional inertia, conformity to habit, resistance to outside influence, the expense to implement agency-wide training, inability to understand the relationship of trauma to professional tasks, and fears of emotional vulnerability/contagion should trauma among staff and clients be acknowledged”(Rich, 2017).

With variability in response generally dependent on the officer or jurisdiction that receives the case, it becomes clear that the impact of trauma-informed training can also vary. It is crucial to assess officers who have undergone such training to determine its effectiveness at an individual level.

Present Study

The present study is an exploration of the perspectives and experiences of law enforcement within the Salt Lake Valley to see how trauma-informed training has impacted them individually. Exploring the narrative accounts of law enforcement might help gain a deeper understanding of whether this new approach has resulted in tangible changes in policing methods and law enforcement perceptions. This inquiry aims to uncover valuable insights and experiences that contribute to the ongoing dialogue about the effectiveness and impact of trauma-informed policing.

Methods

Participants

The study involved three participants: two male detectives and one female detective, all of whom were current or former investigators with experience handling sexual assault and rape cases. All participants were from the same law enforcement agency. A snowball sampling method was used for recruitment. The first participants were identified through personal connections, with their contact information provided by mutual acquaintances. The principal investigator (PI) then reached out to these individuals via email or text to invite them to participate. Additional participants were recruited through referrals from the initial participants. At the end of each interview, participants were asked, “Do you know any officers with experience handling sexual assault cases who might be interested in participating in this study?”. The intent behind using personal connections was to enhance law enforcement engagement, though it may not have been the most effective strategy, as one department and five officers did not maintain communication after the initial inquiry.

Procedures

Semi-structured interviews took place via Zoom or in a private space at the University of Utah, Participants were given the option to choose an interview online or in person. Two interviews were conducted over Zoom, and one was conducted in person. The audio was recorded via Zoom or an audio recording app; recordings were destroyed after data collection.

The interview questions were open-ended and narrative-based. This interview script was inspired by the interview strategies employed in the 2016 study by Quinlan; the questions were intentionally worded to encourage less institutional language and promote more detailed accounts from the participants (Quinlan, 2016). The interviews averaged about 34 minutes and were transcribed in full. They were then evaluated based on common themes.

Participants received the informed consent form via text before the interview to ensure they understood the purpose and procedure of the study, along with the projected risks and their rights as participants. After reviewing the form, participants confirmed their consent to participate. The PI emphasized to the participant that they were able to withdraw from the study at any time, both during the consent process and before the interview began, to ensure their continued voluntary participation. They were also given the opportunity to ask questions during the interview. We also provided the contact information of the PI, IRB, and faculty sponsor to direct further questions after the study.

Findings

Trauma-Informed Training

The participants reported undergoing several types of training, including FIT (Forensic Interview Training), TIVI (Trauma-Informed Victim Interviews), and/or a four-hour intimate partner and sexual violence training. All participants expressed highly positive perceptions of the training they received. One officer shared that they apply the FIT training not only when interviewing individuals who have experienced trauma, but also in all of their interviews, as they view it as an extremely effective model of interviewing. Since completing the different trauma-informed trainings, the participants noted a decrease in complaints against fellow officers and observed greater understanding and cooperation from victims. All participants mentioned that being trauma-informed has shifted their mindset to be more understanding of a victim’s trauma. One officer noted that the trainings they received helped them lose the “jaded” mindset they had developed while working patrol, which they expressed made them question the reliability of many people’s testimonies.

Investigation

Throughout the interviews, participants discussed how the investigation process has evolved when working with victims of sexual assault and rape. One officer expressed that they viewed the training as something that benefited victims by improving law enforcement’s understanding and response to victims, but also as something that has enhanced the investigation process by making it more thorough and informative. Another officer explained that the way they approach questioning victims has shifted to be less “accusatory” of the victim. Previously, the questions that were asked focused on the who, what, where, and why of the crime, but now, they are more open-ended. The officer elaborated, saying, “Believe it or not, [asking who, what, where, type of questions] are kind of accusatory to a victim.” This officer noted that rephrasing questions to invite storytelling of the account of the crime facilitates a more thorough investigation because it invites the victim to provide more information.

Two participants emphasized the importance of the initial inquiry with a victim, expressing that it can make or break their case. One officer explained that they now have veteran officers handle the initial inquiry with rape and sexual assault victims to make sure that victims receive treatment that is empathetic and understanding. The treatment, as explained by the participant, was not only to avoid victim retraumatization by the system, but also to encourage further engagement with law enforcement. They explain, “If you send an officer that has lack of experience, lack of empathy, lack of believing their victim, the likelihood that [victim] will participate with victims advocates, counseling, detectives, prosecution, drops dramatically because of this event”.

Prosecution

The participants were asked, “In your experience, why might a sexual assault case not be referred for prosecution?” The responses varied. One officer explained, “We almost always refer cases unless there is clear, concrete evidence showing that there’s no basis for the accusation.” Officers noted that achieving a successful prosecution can be more difficult when there has been a delay in reporting, when evidence is lacking, or when the perpetrator claims the encounter was consensual, as this can make DNA evidence harder to interpret.

The participants also discussed the changes they have implemented. One officer shared, “We are a mandatory screen, which means that I take a case if it has probable cause, regardless of how unlikely the prosecution, we always push it up.” All three officers expressed that they do something called “staffing the case”, “MDT staffings”, or “SART teams”, where they collaborate with a multidisciplinary team to determine the best course of action for a case. This team typically includes prosecutors, victim advocates, healthcare professionals, attorneys, and others. Some officers also highlighted the involvement of victim advocates in their cases. One officer expressed that there has been a shift in the responsibilities officers have with prosecution; they now claim that there is a 100% referral to prosecution, and they believe that the shift was needed:

Law enforcement did a disservice to the public years ago where they were not only the fact finders, but they were the judge and the jury before it even got sent to the attorney’s office. And so I think fixing that mindset has actually been more beneficial to our communities that we serve and more beneficial to the public because then we’re not taking that all-encompassing role that was really never ours to take to begin with.

Understanding Traumatic Memory

All participants discussed how rape and sexual assault victims may experience memory lapses and a nonsequential order of events due to trauma. One officer shared an explanation similar to the explanation in Dr. Rebecca Campbell’s seminar; they described traumatic memories as being like disorganized sticky notes—fragmented and scattered, making them difficult to recall in a coherent order. One officer explained that there is variability in traumatic memory. They expressed that they look for gaps in memory, nonsequential order of events, and “hesitancy to talk about details, or the overabundance of talking about details”. Another officer explained that traumatic memories are a result of the brain trying to protect the victim.

The participants expressed some changes that they have incorporated to better respond to victims. Two officers mentioned that they now recommend victims get two to three full sleep cycles before providing their account, explaining that rest can improve the accuracy and clarity of their recollection of events. Additionally, all the officers used language that showed they expected and were normalizing traumatic memory recall, “for new officers, the most important part of training is the fact that these events are going to be chopped up and that’s okay… that’s not a sign of them misleading you”.

One officer explained that they expect a certain level of disorganized recall and may even view a person who does not display that as suspicious. The officer stated, “it is more of a red flag to me is if somebody was raped and they come in and give me a perfect chronological story. That’s almost more of a red flag, not always.” Additionally, one participant noted that the concept of traumatic memory may be difficult for newer officers to understand because it deviates from what investigators typically expect:

If I’m interviewing a victim for, let’s say, a carjacking, they are able to give me a linear account: ‘I went to a coffee shop, I was stopped at this light, they came up to my passenger side door, they displayed a gun, I got out, and they left’ So what [law enforcement] looks for is a linear explanation when it comes to a crime. In law enforcement, if your story deviates or changes, you’re often seen as not being quite honest.

Understanding Trauma

Several participants expressed in their interviews an understanding of how trauma can present itself in a victim of sexual violence. One officer explained that trauma can present itself differently depending on the person’s experiences in life: “It depends on their social structure at home, their education, their religious preferences, and how they cope with trauma”. They went further to explain that victims’ emotions can be variable “a victim’s mindset can be anything from crying to laughing to joking to nothing across the board… their initial responses shouldn’t dictate how the case should go.” Another officer shared a case involving two family members who had both endured prolonged trauma at the hands of their parent. Despite experiencing the same traumatic events, their emotional reactions and ability to recall their experiences were starkly different. The officer explained that the experience of interviewing those victims helped articulate to them that “you never know how trauma’s going to affect somebody”.

One officer acknowledged that the police investigation process itself can be traumatizing for victims, particularly due to the repeated retelling of events and the pelvic exam. They emphasized their efforts to approach the situation with empathy, offering support to victims undergoing the exam and helping them regain a sense of personal agency throughout the process.

False Reports

Overall, participants reported that false reports were rare and unlikely. One participant estimated that false reports accounted for less than 10% of cases. Another participant repeatedly mentioned that their training indicated false reports were under 2%, though they were unsure of how that figure was derived. The participant expressed that, from their experience, they have seen that the police report of an assault can be weaponized. Some reasons they provided are that a rape case may be used against religious institutions, or custody or relationship disputes. Despite their hesitancy towards the statistics, they did express that provably false cases were incredibly rare.

In contrast, one participant expressed that they do not have any estimate of false reports because they view that that was not their job; they explained that as “neutral fact-finders,” it is their place to believe people at their word and collect information. They expressed that they were a “different kind of investigator” because they had had conversations with some officers who claimed a victim’s report was tied to ulterior motives, like religious leaders making them feel bad. They expressed, “if someone feels as though that their rights were violated, I might not be able to give them justice. I might not be able to do anything about it, but I have a job to collect what I can collect”.This officer also shared the impact of believing victims’ testimony, noting that they have heard from victims who were surprised by the respectful and supportive treatment they received.

Changes

When asked about additional changes they would like to see happen, two officers expressed that there is a larger need for the training, especially for new officers. One of the officers expressed that trauma-informed training should incorporate victim perspectives, as they believe that hearing the first-person accounts of a victim can help better guide how officers approach new reports and decrease re-victimization. The participant shared details about a training they attended, which included the perspective of a victim who had been disbelieved by the Provo Police Department. They explained that they viewed the training as very powerful because the victim expressed the lasting impacts of being disbelieved. Another participant expressed that they would like to see more role play in the training to better develop skills for handling victims with more understanding and empathy. One officer expressed that they were happy with where they are currently, as they think that the response has dramatically improved.

Discussion

The findings of this study suggest that individuals who have received trauma-informed training hold a positive view of the experience, believing it to be valuable not only for supporting victims but also for enhancing the quality of their investigations. Although perceptions of false reports varied, all officers believed that false reports were either rare or insignificant, which contrasts with prior research ( Edwards et al., 2011; Quinlan, 2016). This suggests that these trainings may have helped reduce this perception. All participants demonstrated an understanding that gaps and non-chronological accounts of rape and sexual assault are signs of trauma and not of dishonesty. They additionally expressed changes that they have incorporated to help facilitate a better investigation informed by trauma’s impact on memory.

Some participants indicated a shift from law enforcement being the sole decision-makers in advancing a case to now forwarding nearly all or the majority of their cases to prosecution. However, the research does not support this claim overall, as the rate of case attrition for victims of sexual violence remains notably low (National Institute of Justice, 2019; Rich, 2019; Westera et al., 2016). Additionally, all participants expressed that they now attend meetings with people from across different aspects of involvement in victim cases. This shows an advancement in law enforcement response. Further investigation is needed to assess the extent to which these practices are being implemented across departments to examine where case attrition is currently.

This research also highlights several areas needing improvement within the law enforcement landscape. The officers suggested changes to training programs, such as incorporating personal accounts from victims and including more role-playing scenarios. Additionally, the officers mentioned improvements their agency has adopted that could be more widespread, like ensuring veteran officers handle the first inquiry with victims, incorporating multidisciplinary perspectives when forwarding a case to prosecution, and encouraging sleep cycles before asking a detailed account of events to promote better recall.

Upon reviewing their interviews, a more thorough explanation is needed regarding the rarity of false rape reports, as one officer expressed some skepticism about the statistics provided. This could increase law enforcement’s confidence in the credibility of the data. Additionally, there may need to be training on situations that appear like there may be ulterior motives for the report, as each participant expressed that there are law enforcement officers who take those factors into account. Furthermore, while the study indicates that law enforcement is aware of traumatic memories in victims’ testimonies, further training is needed to deepen this understanding, as one officer expressed questioning testimony if the victim was not presenting signs of trauma. Research shows that trauma is variable, which could also mean presenting no signs of emotion and being cold (Quinlan, 2016). Strengthening this knowledge would help ensure better handling of trauma-related cases by law enforcement officers.

Limitations

One of the main limitations of this study is the small sample size. The limited number of participants could have affected the results, potentially making the findings less generalizable or leading to skewed conclusions. Additionally, law enforcement personnel were informed about the purpose of the study beforehand. This prior knowledge could have led to a selection bias, as individuals less familiar with or unaware of traumatic memory might have opted not to participate. To improve recruitment in future studies, alternative methods could be explored to enhance participation, like contacting the departments themselves to recruit volunteers. Moreover, the study’s design might have benefited from partial disclosure, as this approach might have provided a more authentic representation of participants’ varied perceptions. Another limitation of this study is that interviews were not experimental in nature, which makes results less reliable. Future research should aim to compare law enforcement personnel who have undergone trauma-informed training with those who have not, possibly by doing a within-subjects design, to better create a comparison of the training.

Conclusion

Historically, the criminal justice system has been characterized by the widespread failure to provide justice for rape and sexual assault victims. Central to this problem is a broad misunderstanding of how traumatic memories affect a victim’s statement. Trauma profoundly influences the encoding and consolidation of memories, resulting in disorganized and fragmented recall. This misinterpretation has long persisted in police practice, leading to the disbelief of victims. However, there is promise in embracing a trauma-informed approach to interviewing victims.

Although there are limitations to the current study, this study does provide insight into the individual experiences of law enforcement who have received trauma-informed training. All participants had a positive outlook on the training that they had received and reported seeing positive responses from victims. Participants expressed feeling like trauma-informed training had changed not only how they approached the interview process, but also their viewpoints as interviewers. Law enforcement additionally all had an accurate understanding of trauma and traumatic memory and believed false reports were low. The study indicates some areas that could benefit from improvement, such as better explanations of statistics, having initial victim interviews done by veteran officers, and incorporating victims into the trainings. Mandating and effectively integrating trauma-informed training on a wide scale may help enhance law enforcement’s interaction with victims, decrease chances of re-victimization by the system, and ultimately ensure victims receive the justice they rightfully deserve.

Acknowledgments

A big thank you to my faculty sponsor, Dr. Heather Melton, who has helped guide me in every step of my research, and a special thanks to the Office of Undergraduate Research for supporting this research. And lastly, my family for helping me throughout my education journey.

Bibliography

Edwards, K.M, Turchik, J. A., Dardis, C. M., Reynolds, N., & Gidycz, C. A. (2011). Rape Myths: History, Individual and Institutional-Level Presence, and Implications for Change. Sex Roles, 65(11-12), 761–773. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-9943-2

Herman, J.L. (1992). Trauma and Recovery. Basic Books.

International Association of Chiefs of Police. (2020). Final design successful trauma informed victim interviewing. https://www.theiacp.org/sites/default/files/2020-06/Final%20Design%20Successful%20Trauma%20Informed%20Victim%20Interviewing.pdf

Leithead, K. (2022, November 10). False reports – percentage. EVAWI. https://evawintl.org/best_practice_faqs/false-reports-percentage/

Lovell, R.E. & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J. (2023). Sexual Assault Kits and Reforming the Response to Rape (1st ed., Vol. 1). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003186816

National Institute Of Justice. (2013). Interview with Dr. Rebecca Campbell on the Neurobiology of Sexual Assault (1 of 3) [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved October 29, 2023, from https://youtu.be/khUfN58RUo8?si=U2L_fzr7FMLGnkPQ.

National Institute Of Justice. (2019). The Neurobiology of Sexual Assault: Implications for First Responders [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved November 4, 2023, from https://youtu.be/QuirVpIhl0g?si=7qZRWGjOev-zp7tz.

Meadow, R. (2023, July 26). What is police reform?. Police Brutality Center.https://policebrutalitycenter.org/what-is-police-reform/#:~:text=Police%20reform%20comprises%20measures%20that,to%20operate%20safely%2 0and%20efficiently.

Miller, T. C., & Armstrong, K. (2015, December 16). An unbelievable story of rape. ProPublica. https://www.propublica.org/article/false-rape-accusations-an-unbelievable-story

Payne, B. (2023). Lecture Slides for Memory. Lecture.

Quinlan. (2016). Suspect Survivors: Police Investigation Practices in Sexual Assault Cases in Ontario, Canada. Women & Criminal Justice, 26(4), 301–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/08974454.2015.1124823

Rich, K. (2019). Trauma-Informed Police Responses to Rape Victims. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 28(4), 463–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2018.1540448

The Sexual Assault Kit Processing Act, Utah Code Section 53-10-908 (2023). Utah Code Section 53-10-908

Turvey, B.E. & Savino, J. O. (2014). Rape Investigation Handbook. Academic Press.

Appendix A

Interview Script

The interviewer will begin the recording and proceed with the following script for the interview:

Hello, thank you so much for taking the time to meet with me today. I appreciate your willingness to participate in our study. Before we get started, I just want to make sure you’ve received and reviewed the informed consent form. Do you have any questions about it? As a reminder, participation in the study is voluntary and you can stop at any time in the interview. Please feel free to take your time and share as much or as little as you would like. If there’s anything you don’t want to answer or if you need clarification on a question, just let me know. Ready to begin?

2. What is your experience with sexual assault cases?

3. What has your training for handling rape and sexual assault cases looked like?

5. In your experience, why might a sexual assault case not be referred to prosecution?

6. Can you estimate the prevalence of false reports of sexual assault?

7. What signifies to you that a case is truthful? What signifies that it is not?

8. Have you heard of traumatic memory?

10. Is there anything that I did not ask that you would like me to know?

That concludes our interview. It was wonderful speaking with you today. If you have further questions, please feel free to contact me, the faculty sponsor, or the IRB. Thank you so much for your time today and your willingness to participate in our study.

The interviewer will stop the recording here.

The interviewer will then ask at the end of the interview: Do you know any officers that you know have dealt with sexual assault cases that you believe would be interested in also participating in the study?