College of Social and Behavioral Science

122 Examining Program Quality as a Predictor of Developmental Growth Among Youth Participating in a School-Based Camp Program

Sarah Herring

Faculty Mentor: Robert Lubeznik-Warner (Psychology, University of Utah)

ABSTRACT

Youth programs are an opportunity to foster positive developmental outcomes such as social skills, goal setting, and optimism for the future. Program quality—staff behaviors and practices at the point of interaction with youth—supports these developmental outcomes. At the Tim Hortons Foundation Camps, program quality is measured by the presence of safety, support, interaction, and engagement. Understanding how program quality relates to outcomes for youth from low-income families may inform areas for improvement. The purpose of this study was to examine how elements of program quality impact youth outcomes, specifically intrapersonal and interpersonal outcomes. We hypothesized that (1) measures of program quality will predict change in self-report measures of self-efficacy and prosocial behavior from the beginning of the program to the end, and (2) measures of program quality will predict retrospective self-perceived interpersonal and intrapersonal growth measured after participation in the program. This study used pre-post survey data collected from over 700 students, ages 9–12, from low-income backgrounds who participated in a Tim Hortons Foundation Camps in-community program during the fall of 2024. The study used program quality measures (safe, supportive, interaction, and engagement) to predict change in youth development outcomes (self-efficacy, prosocial behavior, interpersonal and intrapersonal growth). Data were analyzed using an ordinary least squares multiple regression. The study findings highlight the significant role that program quality, specifically safe and supportive programming, plays in social-emotional development among youth. The greater presence of youth perceptions of physical and emotional safety and support, the greater developmental impacts these experiences were found to have, thereby reducing the gaps in developmental opportunities for youth from differing socio-economic backgrounds. This research and understanding can inform future research on youth development, advise policy implementation, and lead to evidence-based practices for youth programs, especially in contexts promoting positive development.

INTRODUCTION

The adolescent years represent an important phase of development, displaying rapid growth, transformation, and brain development. This period lays the groundwork for future behaviors that can be either beneficial or detrimental throughout life (Dahl et al., 2018; Vijayakumar et al., 2018). Youth programs are an opportunity to foster positive developmental outcomes for youth such as the way they interact with others, set goals for themselves, and develop optimistic future expectations. Social-emotional learning programs are designed to enable youth to manage their thoughts, establish and achieve goals, empathize with others, build and maintain healthy relationships, and make responsible choices (Weissberg et al., 2015). SEL is linked to enhanced self-perception, greater social and emotional competencies, and improved prosocial behavior and academic success. Additionally, it is associated with reduced emotional distress, risks, and problematic behaviors (Bonell et al., 2016; Mendelez-Torres et al., 2016; Weissberg et al., 2015).

Summer camp is one common type of youth programming which supports SEL. Research suggests that summer camp is connected to the development of social skills, emotional competencies, and positive self-perception (Wilson et al., 2019). Studies indicate the achievement of similar developmental outcomes for youth from low-income backgrounds in comparison to youth from more affluent backgrounds (Warner et al., 2021). In efforts to make summer camp more accessible to youth from various backgrounds, identities, and socio- economic status, it is critical to understand if bringing camp programming to schools may have the same positive outcomes—and what aspects of the programming might support these outcomes.

It is not enough to suggest that youth programs foster positive development for adolescents without also considering the quality of these programs. Program quality—staff behaviors and practices at the point of interaction with youth—support these developmental outcomes (Bennett, 2012). High-quality programs are characterized by supportive relationships, engaging activities, interactive atmosphere, and a safe environment. When these elements are present, young people are more likely to develop important social and emotional skills, build self-confidence, and foster positive peer relationships (Sparr et al., 2020). Conversely, low- quality programs may fail to engage participants and lead to less favorable developmental outcomes or none at all. Therefore, investing in the quality of youth programs can significantly enhance the overall development and well-being of young people. The relational developmental systems theory (Lerner & Overton, 2008) explains the relationship between program quality and growth outcomes, suggesting that the interactions of youth and their environments are determinants of positive development. In this study, we sought to examine what elements of program quality impact youth outcomes.

Social-Emotional Developmental Outcomes

It is critical to understand youth development as behaviors and habits formed during adolescence can be highly indicative of success in later life (Shi & Moody, 2016). Many youth programs utilize methods of social-emotional learning which go beyond educational teaching and target the development of skills necessary to manage emotions, set goals, and build relationships. In addition to fostering knowledge and academic skills, schools should support the enhancement of students’ social-emotional competencies (Greenberg, 2010; Farrington et al., 2012).

Previous studies about SEL at summer camp suggest that interpersonal and intrapersonal development can occur at camp (Wilson et al., 2019). Interpersonal development involves interacting with others in a manner that creates support, belonging, and positive relationships. Intrapersonal development includes the cultivation of self-efficacy, or the positive belief in one’s ability to successfully achieve what one sets out to accomplish.

Prosocial Behavior

Prosocial behavior is defined as voluntary, desirable actions intended to benefit others (Luengo et al., 2021). Based on Eisenberg’s model of prosocial development, there is a reciprocal relationship between moral development and prosocial behavior (Brestovansky et al., 2022). For example, as adolescents develop empathic tendencies, they become more prosocial, which in turn makes them more empathic, and so on. This theory suggests that participating in prosocial activities enhances empathy and social understanding. Additionally, prosocial behavior—being correlated with school engagement (Caprara et al., 2000)—is connected to higher academic achievement. Learning to act prosocially from a young age has been shown to promote high measures of well-being and academic achievement (Kiuru et al., 2020). Fostering prosocial behaviors through programs that promote social responsibility and community involvement aids in the cultivation of holistic youth development, as emphasized by the positive youth development framework (Scales et al., 2006, Eccles & Gootman, 2002, Mahoney et al., 2004).

Youth programs, such as summer camps, create opportunities for developing prosocial tendencies, ultimately contributing to healthier social relationships and a stronger sense of community among participants (Geldhof et al., 2014). Summer camp programming provides an environment for youth to interact with peers from diverse backgrounds which is a catalyst in the development of empathy, communication skills, and collaboration on common goals. This is shown to be a space where kids can comfortably express emotion and learn to regulate intense feelings (Eccles & Gootman, 2002). Camp-like environments also provide a safe space for youth to take social risks and try new things (Kirchhoff et al., 2024, Povilaitis & Tamminen, 2018).

It is necessary to understand the implications of the program environment to better understand how we can improve the facilitation of prosocial behavior within these youth programs. It is understood that the camp setting promotes prosocial tendencies at camp and years down the road (Povilaitis et al., 2023). In the efforts to improve access to camp-like programming for all, camp-facilitated school programs reach youth from diverse backgrounds, identities, and socio-economic statuses. More research is needed to understand the specific elements of school-based camp programming that contribute to prosocial behavior.

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in their ability to succeed in specific situations or accomplish tasks (Bandura, 1997). Self-efficacy can influence motivation, learning, and behavior. For youth, self-efficacy has been linked to academic success, increased motivation, and self-regulation. Studies show that those with greater self-efficacy are often more persistent in the face of challenges and experience better educational outcomes (Pajares & Schunk, 2001; Zimmerman & Kitsantas, 2005). Furthermore, self-efficacy shapes children’s aspirations and career trajectories (Bandura et al., 2001), indicating that it plays a crucial role in personal and professional development. Fostering self-efficacy in youth can contribute to their success, resilience, and well-being as self-efficacy in early life is correlated with stress moderation and associated with life satisfaction (Moksnes et al., 2019).

Youth programs like camp cultivate an environment for kids to build confidence and self- efficacy. The camp setting—full of opportunities to try new things, learn new skills, work with teams—is optimal for the cultivation of this self-efficacy, as mastery experiences are critical for the development of belief in oneself (Hattie et al., 1998, Larson, 2000). Through adventurous activities and social challenges, camp staff inspire youth to step outside of their comfort zones, which aids in the development of resilience, and in turn, self-efficacy (Zimmerman, 2000, Geldhof et al., 2014). Lastly, camp environments offer a unique opportunity for social support and a sense of belonging through team building and mentorship. These relationships reinforce social support and affirm a youth’s abilities. The presence of self-confidence is a strong predictor of personal efficacy beliefs (Pajares & Schunk, 2001). Youth who participate in camp programs report increased self-confidence and a greater belief in their ability to succeed (Richards et al., 2014).

As with prosocial behavior, more research is needed to understand what features of program quality contribute to increases in self-efficacy. Although current literature links specific mechanisms in camp programs to self-efficacy, little is known about how these mechanisms may function in school-based camp programs. This information is critical to inform new program designs. It is important to address these gaps to better understand how camp-based programs foster self-efficacy in young people, which in turn could lead to more effective program development and improved results for youth.

Program Quality

Theories of human development emphasize that personal growth is shaped by the interactions individuals have with their environments. The relational developmental systems theory suggests that individuals and their environments influence each other and that the interaction between individuals and their environments shapes development (Lerner & Overton, 2008), suggesting that to fully understand the outcomes of youth developmental programming, we must thoroughly evaluate program quality (Arnold & Gagnon, 2020, Borden et al., 2014).

Relational developmental systems theory emphasizes the importance of complex relationships between individuals and their contexts, whether those be biological, psychological, social, historical, or in this case, environmental. Relational developmental systems theory would suggest that there is a relationship between program quality and youth developmental outcomes. For this study, we operationalized program quality as safe, supportive, interactive, and engaging environments, and operationalized developmental outcomes as prosocial behavior, self-efficacy, and overall perceptions of growth.

Program quality refers to the effectiveness of youth programs in delivering intended outcomes (Eccles & Gootman, 2002). This encompasses various aspects, including the curriculum, staff, and the environment in which the program operates. According to the National Research Council and Institute of Medicine (2002), quality programs are essential for fostering positive youth development and ensuring that young people gain the skills they need to thrive. Program quality is connected to social-emotional learning, because of the focus on developing essential skills such as self-awareness, empathy, and interpersonal skills.

Using the pyramid of instructional quality (Smith et al., 2012), research breaks down the levels of environmental quality emphasizing the importance of the program being safe, supportive, interactive, and engaging. As outlined, facilitation of these environments can involve many different techniques such as providing a welcoming atmosphere, supporting physical, emotional, and psychological safety, creating small groups, partnering with adults, and promoting leadership opportunities. When these elements are present in programs, they are considered to be high-quality and have the likelihood of supporting learning and development.

A safe environment is essential for positive development, as it allows young people to participate and take social risks without fear of physical or emotional distress. Research emphasizes that when youth feel physically and psychologically safe, they are better equipped to build positive social skills rather than defensive behaviors (Eccles & Gootman, 2002). The cultivation of respect and inclusion in youth environments can encourage active participation (NASEM, 2019) along with a foundation for emotional resilience, sense of belonging, and identity formation due to an experience of freedom to fully express themselves without fear of judgement (Durlak et al., 2010). In sum, safety appears to be a prerequisite for developing social and emotional skills that contribute to favorable youth development.

When youth programs nurture relationships with caring adults and peers they are more likely to foster emotional and psychological safety. Supportive environments offer individuals encouragement and emotional support, which are critical for building self-confidence and resilience (Rhodes, 2002). Studies suggest that when youth feel supported by adults and peers, they are more likely to develop social-emotional skills such as self-discipline, compassion for others, and problem-solving abilities (Durlak et al., 2011). Additionally, supportive relationships with adults and peers provide youth with a sense of stability and trust, which can help them navigate challenging situations with confidence. These environments reinforce positive identity development and help youth develop the competencies and life skills necessary in the long-term (Roth & Brooks-Gunn, 2003).

Interactive environments are characterized by opportunities for youth to actively participate with peers and adults through collaboration, open discussion, and hands-on activities. Literature on youth programs highlights that interactive settings promote the development of social skills, as they allow youth to practice communication and teamwork (Hurst et al., 2013). When young people have opportunities to share ideas, work as a team towards collective goals, and resolve conflicting views, they gain a sense of agency and confidence in navigating social relationships (Larson, 2000), further fostering autonomy and self-efficacy through the practice of leadership and active decision-making. This not only builds critical social competencies but also fosters a sense of community and belonging, both of which are key to positive youth development (Eccles & Gootman, 2002).

Engaging environments are those that capture youth interest and foster curiosity. Research shows that when youth find program activities stimulating, they will participate more consistently and show greater motivation to learn (Durlak et al., 2010). Engaging environments often include opportunities for decision-making and creativity, encouraging students to think and reflect on concepts as they learn. This action may reinforce feelings of autonomy and ownership over their development and education (Li & Julian, 2012). Ultimately, engagement in youth programs is associated with better social-emotional learning outcomes, as it leads to greater investment in lessons and activities within programs and classes (Roth & Brooks-Gunn, 2003).

High-quality programs create environments where young people can practice and reinforce social-emotional skills in real-world contexts. For instance, programs that emphasize safety, support, interaction, and engagement provide youth with the tools to build self-discipline and navigate social situations effectively. By focusing on quality programming, we can create environments that foster the growth of essential skills, such as self-efficacy and prosocial behavior.

Present Study

While it is clear that camp programs can contribute to enhanced self-efficacy, most research involves samples of campers and students from high socio-economic status backgrounds. There is a lack of research pertaining to kids from low-income backgrounds. Given the evidence suggesting links between program quality and developmental outcomes, as well as the importance of youth programming that fosters opportunities for SEL among youth from low- income backgrounds, we sought to identify the mechanisms by which high-quality school-based camp programs support interpersonal and intrapersonal outcomes. To provide a more holistic and robust examination of these relationships, we considered change through pre-post measures and retrospective self-perception of growth in outcomes. Specifically, we hypothesized:

Hypothesis 1: Youth perceptions of program quality will predict the change in self-report measures of interpersonal and intrapersonal development from the beginning of the program to the end.

Hypothesis 2: Youth perceptions of program quality will predict retrospective self-perceived interpersonal and intrapersonal growth measured after participation in the program.

METHOD

This study employed a pre-post design to assess changes in self-efficacy, prosocial behaviors, and overall growth among students participating in the Tim Hortons Foundation Camps In-Community program. The students completed surveys at two time points: (1) before starting the 7-week program, and (2) following the program’s completion.

Participants

Tim Hortons Foundation Camps In-Community program serves schools with a high proportion of students from low-income backgrounds. Schools were selected from priority regions identified by the presence of Tim Hortons restaurants, paucity of social-emotional skill development programs, and a lack of proximity (not within driving distance) to a Tim Hortons Camps property. The Tims Camps Strategic Advisor, a former Director of Education at one of Canada’s largest school boards, reached out directly to principals at these schools to determine interest in the program for grade 5 and 6 students. If inclusion criteria were met and there was interest from the principal, a meeting was set up to discuss the program and determine the next steps for launching the program at that school.

Demographic information, including age and gender, was collected for students. Students who completed the pre-program survey had ages ranging from 9–12 years, with a mean age of 10.34 (SD = .64). This sample of students was comprised of 399 boys (50%), 369 girls (46%), and 12 students who identified as non-binary (2%). Students with matched post-program survey responses (430 students completed both pre- and post-surveys) were an average age of 10.32 (SD = .96) and consisted of 207 boys (49%), 201 girls (48%), and 5 non-binary students (1%). It is important to note that these programs serve schools with a high percentage of students from low socioeconomic backgrounds.

Table 1. Demographics

|

Variable |

Pre (n = 828) |

Post (n = 664) |

||

|

|

M (SD) |

n (%) |

M (SD) |

n (%) |

|

Age |

10.34 (.64) |

– |

10.32 (.64) |

– |

|

Boy |

– |

399 (50%) |

– |

207 (50%) |

|

Girl |

– |

369 (47%) |

– |

201 (48%) |

|

Non-binary |

– |

12 (2%) |

– |

5 (1%) |

Note. Demographics were not asked on the post survey, limiting all demographic information for the post survey to only matched responses. Given the Canadian context of this study, and their regulations around asking about racial identity, this information was not collected.

Procedure

Students were invited to participate in the 7-week program and asked to complete a brief survey before the first session and after the program ended. Teachers and program staff administered the survey, and students had an opportunity to opt out. Parents/Guardians provided permission for their child to participate in the program. Students who did not have permission were provided with another activity during the program. Given that these data were initially collected anonymously for organizational evaluation purposes and not for research purposes, this secondary analysis of the anonymous data did not require IRB approval.

Materials

For data collection purposes, a survey instrument comprising two short-form/adapted scales measuring self-efficacy and prosocial behavior, self-perceived growth outcomes measuring reflective interpersonal and intrapersonal growth, and student-reported scale of program quality measures was used.

Self-Efficacy

To obtain an average score for self-efficacy, we utilized the 10-item General Self- Efficacy Scale (Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1995), which assesses participants’ confidence in handling challenges and achieving tasks. The scale was adapted to be more engaging and relatable for younger participants, enhancing their ability to understand and respond accurately. Items were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (Never/Almost never true) to 5 (Always/Almost always true). Example items include statements like, “I can manage problems if I try hard” and “I can stay calm when things are hard because I know what to do.” In this study, the reliability of this scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of α = .88 on the pre-program survey and of α = .89 on the post-program survey, indicating satisfactory internal consistency.

Prosocial Behavior

The survey also included a modification of the Prosociality Scale (Luengo-Kanacri et al., 2021), originally a 16-item scale used to assess a person’s propensity to behave prosocially and engage in positive social interactions with others. The revised scale used for evaluation of Tim Horton Camp’s Foundation in-community programs included 4 items rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (Never/Almost never true) to 5 (Always/Almost always true). Example items include statements like, “I try to include others in conversations and activities” and “I try to help those who are in need.” In this study, the reliability of this scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of α = .78 on the pre-program survey and of α = .77 on the post-program survey, indicating satisfactory internal consistency.

Self-Perceived Growth

Self-perceived growth was measured for interpersonal and intrapersonal domains. To measure the construct of interpersonal development, we used five self-report measures based on the amount that a student experienced growth in the areas of (1) working as part of a team, (2) listening to new ideas, (3) communicating with classmates, (4) sharing my opinion, and (5) respecting others. To measure the construct of intrapersonal development, we used five self- report measures based on the amount that a student experience growth in areas of (1) setting goals, (2) working toward my goals, (3) knowing what I’m good at, (4) understanding my ability to impact my school with my actions, and (5) taking responsibility for my actions.

Program Quality

Program quality was measured using four student-reported scores related to categories of program quality. These categories included: physical and emotional safety (safe), supportive environments (supportive), peer and mentor interaction (interactive), and engagement in lessons and activities (engaging). Students were asked to report how often they feel the Tim’s Camps leader did things to: “help you feel safe to be who you are,” (safe); “help your class become closer,” (supportive); “help you feel interested in what you are doing,”(interactive); “help you feel excited about what you are doing” (engaging). Items were measured on a 4-point scale of frequency (never, rarely, sometimes, always).

Data Analysis Plan

Following data collection, the dataset was cleaned, and participant IDs were matched. All analyses were performed using RStudio. An alpha level of 0.05 was set for determining statistical significance. Descriptive statistics were calculated to summarize participant demographics and pre-post scores for self-efficacy, prosocial behavior, perceived program quality, and interpersonal and intrapersonal growth outcomes.

To answer the research questions, we conducted two sets of analyses. For the pre-post data, we calculated a mean score for dependent variables self-efficacy and prosocial behavior at both time points using measures from the modified Generalized Self-efficacy Scale and revised Prosociality scale. We then computed a raw change score for each construct by subtracting the pre-program means from the post-program means. We then regressed the raw changes scores onto the program quality measures using an ordinary least squares multiple regression. For the perceived growth measures, we calculated a mean score for both interpersonal and intrapersonal growth. We then regressed each of the growth outcomes (interpersonal and intrapersonal) onto the program quality measures.

RESULTS

The purpose of this study was to determine the relationships between program quality and social-emotional outcomes. Overall, our results suggested that program quality predicted outcomes.

Descriptives

From the pre-program survey (n = 828), we calculated a mean score of 3.80 for prosocial behavior (SD = .87) and 3.53 for self-efficacy (SD = .78). From the post-program survey (n = 664), we calculated a mean score of 3.74 for prosocial behavior (SD = .88) and 3.58 for self- efficacy (SD = .81) with change means (n = 400) of -.09 (SD = .76) for prosocial behavior and .07 (SD = .64) for self-efficacy. From self-perceived growth measures (n = 664), we calculated a mean score (range of 1–5) of 3.87 (SD = .87) for interpersonal change and a mean score of 3.66 (SD = .87) for intrapersonal change. Measures of program quality were reported on the post-program survey with mean scores for safe (M = 3.39, SD = .78), supportive (M = 3.23, SD = .85), interactive (M = 3.39, SD = .74), and engaging (M = 3.41, SD = .78).

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics for Key Study Variables

|

Variable |

Pre |

Post |

Change |

|

|

(n = 828) |

(n = 664) |

(n = 400) |

|

|

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

|

Prosocial Behavior |

3.80 (.87) |

3.74 (.88) |

-.09 (.76) |

|

Self-efficacy |

3.53 (.78) |

3.58 (.81) |

.07 (.64) |

|

Interpersonal Change |

– |

– |

3.88 (.86) |

|

Intrapersonal Change |

– |

– |

3.68 (.85) |

|

Safe |

– |

3.39 (.78) |

– |

|

Supportive |

– |

3.23 (.85) |

– |

|

Interactive |

– |

3.39 (.74) |

– |

|

Engaging |

– |

3.41 (.78) |

– |

Note. Ranges: Prosocial behavior = 1–5; General Self-Efficacy = 1–5; Prosocial Behavior Change = -3–2.85; General Self-Efficacy Change = -3.2–2; Interpersonal = 1–5; Intrapersonal = 1–5; Safe = 1–4; Supportive = 1–4; Interactive = 1–4; Engaging = 1–4

Pre-Post Measures

To test H1 (program quality will predict change in interpersonal and intrapersonal outcomes from the beginning of the program to the end), we assessed student-reported measures of pre- and post-program measures of self-efficacy and prosocial behavior. We found program quality elements were significant predictors of change in outcomes.

We found that program quality was a significant predictor of prosocial behaviors (adj. R2 = .23, F (7, 344) = 16.13, p < .001). Specifically, we found the perceived safety of a program to be a predictor of prosocial behavior change scores (ß = .15, p < .001). The perceived support (ß = .08, p = .22), interactive (ß = .10, p = .11, and engaging (ß = .08, p = .18) of a program were not significant predictors of prosocial behavior change scores. These results control for pre- program prosocial behavior (ß = -.50, p < .001), identity as a boy (ß = .04, p = .46), and age (ß = .00, p = .88).

We found that program quality was a significant predictor of self-efficacy (adj. R2 = .25, F (7, 359) = 18.11, p < .001). Specifically, we found that the perceived safety of a program to be a predictor self-efficacy change scores (ß = .20, p < .001) along with perceived supportive environment (ß = .12, p = .04) and engaging (ß = .12, p = .05). There was not a significant relationship between self-efficacy and the extent to which the program was rated by students to be interactive (ß = .03 p = .63). All effects control for pre-program self-efficacy scores (ß = -.51, p < .001), identity as a boy (ß = .01, p = .82), and age (ß = .14, p < .01).

Self-Perceived Growth Measures

To test H2 (program quality will predict retrospective perceived growth in interpersonal and intrapersonal development from the beginning of the program to the end), we used student- reported measures of developmental change. We found that program quality elements were significant predictors of self-perceived growth.

Using the self-perceived growth scores for interpersonal development, we found that program quality were significant predictors of interpersonal growth (adj. R2 = .25, F (6, 345) = 20.75, p < .001). When students report a program to be safe (ß =.23, p = .04), supportive (ß = .17, p < .001), and interactive (ß = .15, p = .02), there were significantly higher levels of self-perceived interpersonal growth. Whether the student found the program to be engaging was not a significant predictor (ß = .10, p = .13). These relationships controlled for the effects of identity as a boy (ß = .00, p = .83) and age (ß = .04, p = .36).

Using the self-perceived development scores for intrapersonal development, we found that measures of program quality were predictive of self-perceived intrapersonal growth (adj. R2 = .25, F (6, 328) = 19.49, p < .001). When students reported a program to be safe (ß = .22, p < .001), and supportive (ß = .21, p < .001), and engaging (ß = .13, p < .04) there were significantly higher levels of self-perceived intrapersonal growth. The relationship between an interactive environment and perceived intrapersonal growth is notable, but not significant (ß = .08, p = .21). These effects controlled for the relationship between identity as a boy (ß = .02, p = .74) and age (ß = .06, p = .24).

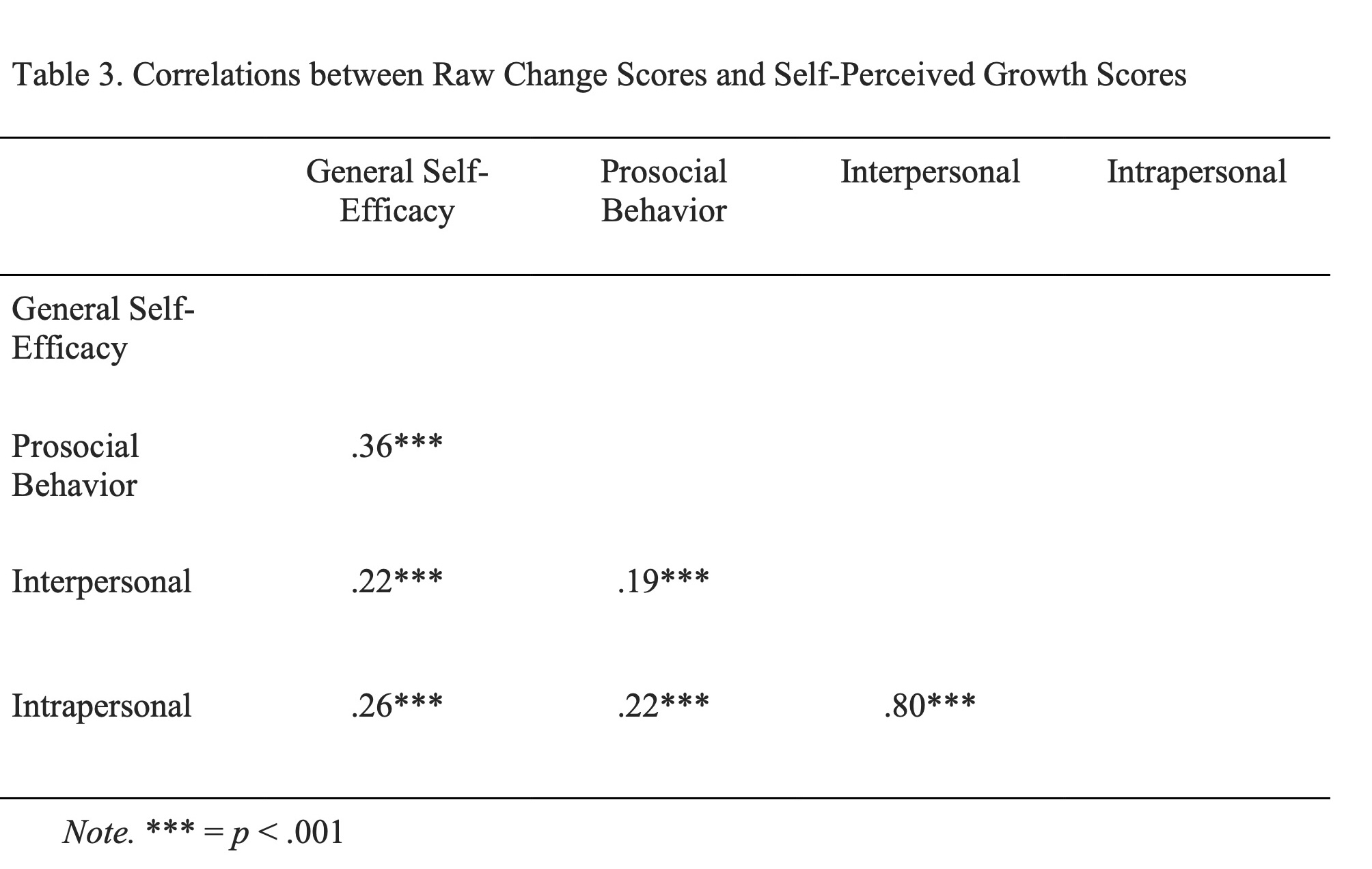

The correlation analysis between raw change scores and self-perceived growth scores shown in Table 3 reveals significant relationships. General self-efficacy shows a strong positive correlation with prosocial behavior (r = .36, p < .001), indicating that individuals who perceive an increase in their general self-efficacy are also likely to exhibit greater prosocial behavior.

Additionally, interpersonal growth is positively associated with both general self-efficacy (r = .22, p < .001) and prosocial behavior (r = .19, p < .001), suggesting that improvements in these areas coincide with enhanced interpersonal skills. Intrapersonal growth demonstrates significant positive correlations with all measured variables, including general self-efficacy (r = .26, p < .001), prosocial behavior (r = .22, p < .001), and interpersonal growth (r = .80, p < .001), highlighting the interconnected nature of these personal development dimensions. These findings underscore the strong associations between self-efficacy and prosocial tendencies, and interpersonal and intrapersonal growth.

Table 3. Correlations between Raw Change Scores and Self-Perceived Growth Scores

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to understand the effects of program quality on developmental outcomes for youth from low-income backgrounds. The findings of this study largely supported the hypotheses that measures of program quality predict both longitudinal and self-reflective changes in interpersonal and intrapersonal development. The purpose of this discussion is to examine study results for each measure of program quality, call attention to potential study limitations, and to discuss the practical implications of these findings for future research, policy, and practice.

The results emphasize the importance of physical and psychological safety in youth SEL programming. Feeling safe in an environment may contribute to risk-taking both in personal ambitions and in social settings, which would lead to greater self-efficacy and prosocial behaviors. This idea aligns with past research which suggests that secure and supportive environments are fundamental in building self-confidence, resilience, self-regulation, and empathy, (Rhodes, 2002, Durlak et al., 2011). The consistently significant impact of safety and support over other measures suggests that feeling secure and supported may be prerequisites for meaningful participation and social-emotional development. In particular, the results suggest that perceived safety within the program is a significant predictor of prosocial behavior (interpersonal development) and self-efficacy (intrapersonal development).

The study results reinforce the idea that conditions of emotional and psychological support appear to influence developmental change. Students’ perceptions of the program being safe and supportive significantly predicted longitudinal change in self-efficacy, along with self- perceived interpersonal and intrapersonal growth. These findings align with previous studies which highlight the importance of safe and supportive environments in the cultivation of social- emotional development among youth (Eccles & Gootman, 2002; Larson, 2000). The consistent positive relationship between the perceived support of the program and self-perceived measures of interpersonal and intrapersonal growth suggests that feelings of support within youth programs is a critical element for youth to recognize their own growth.

While this study aligns with research suggesting that program quality fosters the development of social-emotional skills, it does not support the notion that all elements of program quality contribute equally. Contrary to hypotheses, the program quality elements of interactive and engaging environments within the program were not consistent predictors across all outcome measures. These results deviate from existing literature that emphasizes interactive and engaging environments as key components of youth development (Durlak et al., 2010). Although interactive and engaging environments are believed to be essential, these aspects of program quality may not be as easily recognized by students compared to feelings of safety and support, therefore making them less useful predictors in this study.

Limitations

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the study results. First, all study data consisted of self-reported measures which assume a participant has the ability to accurately assess and recall their previous experiences and states of belief. As a result, it is possible that students may have reported levels of growth that are biased in favorable directions due to social desirability bias, which may limit the validity of the study findings. Due to the nature of pre-post surveying, students may perceive themselves to have grown in self-efficacy or prosocial behavior but not accurately recall their initial self-assessments before the program.

Without being reminded of their pre-program responses, students might provide lower or equal ratings based on their current perspective rather than in retrospective comparison (Sibthorp et al., 2007). As a result, differences in pre-post scores may include more error, making interpretation of these results more tentative. Relatedly, variability in youth responses could have resulted from how students interpreted survey questions rather than from perceived differences in program quality.

Second, were collected from Tim Horton Foundation Camps programming, which also influences the generalizability of findings as these may not extend to all social-emotional learning programs. Further, the program’s structure—being affiliated with Tim Hortons Foundation Camps—may have introduced selection biases, as participating schools and students were those with administrators already interested in social-emotional skill development. In addition, the student’s race/ethnicity was not recorded. Collecting these demographic characteristics contributes to the relevance and application of findings across diverse populations.

Third, program attendance was not recorded or factored into participant criteria. This means that it is possible that any student who attended the first and last program days would record data for growth measures, even if they were not present at any other sessions. In future studies, attendance, or “dosage,” should be a necessary factor in participation criteria to increase validity and mitigate the effects of confounding variables.

Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice

Future research should investigate the mechanisms through which program safety influences development. For example, which aspect of program facilitation creates a perception of safety among students and why do these contribute to growth outcomes? Given the disconnect between interactive and engaging environments and outcomes for this sample, future research could explore whether interaction and engagement play a stronger role in other settings or age groups. Additionally, longitudinal studies with more diverse populations and experimental designs would help clarify the causal pathways between program quality measures and developmental outcomes. As this study reported only initial growth directly after the program, a longitudinal study could examine the durability of the results and implications of outcome persistence. Future studies should explore how opportunity differences like prior experiences and other outside-of-class programs and activities (e.g., sports practices, clubs, summer camps) may influence the impact of these types of school-based programs on social-emotional growth.

The findings of this study can inform better policy interventions aimed at supporting youth from underserved communities. High-quality community-based youth programs can mitigate some of the challenges faced by children from low-income backgrounds. These results reinforce the importance of fostering a safe and supportive environment in youth programs, particularly for underserved populations. With the objective to enhance self-efficacy and prosocial behavior, policy makers should focus on program implementation and training strategies that ensure physical and emotional security as a prerequisite for quality programming.

Given the positive relationships observed between perceived safety and developmental outcomes, educators, practitioners, and program designers should emphasize discussions on how to cultivate environments of perceived safety to expand students’ comfort zones. This allows students to take more social risks and develop confidence that they have a place within their communities. This also allows for the maturation of personal goals and ambitions to evolve into attainable objectives for developing youth. The implementation of such school-based programs may create informal professional development opportunities for classroom educators through observing and discussing the importance of program quality with the staff facilitating these types of experiential programs.

Conclusion

We conducted this study to better understand the elements of program quality that contribute to positive growth outcomes for students participating in a camp-informed, classroom- based social-emotional learning program—specifically how students’ perceptions of program quality may promote interpersonal and intrapersonal development. The study findings highlight the significant role that program quality, specifically safe and supportive programming, plays in social-emotional development among youth. Cultivating a safe and supportive environment is one of the most important tasks when working with youth as they develop confidence, responsibility, and positive social behaviors. The study results highlight the potential value of quality youth programming as a way to provide social-emotional learning opportunities for youth from low-income backgrounds. The more youth perceive these programs to be of high quality, the greater impact these experiences can have, thereby reducing the gaps in developmental opportunities for youth from differing socio-economic backgrounds.

Bibliography

Arnold, M. E., & Gagnon, R. J. (2019). Illuminating the process of youth development: The mediating effect of thriving on youth development program outcomes. Journal of Human Sciences and Extension, 7(3), 24.

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (2001). Self-efficacy beliefs as shapers of children’s aspirations and career trajectories. Child Development, 72(1), 187–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00273

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bennett, T. (2012). Staff practices of high quality youth programs. Briefing paper prepared for the American Camp Association.

Bonell, C., Hinds, K., Dickson, K., Thomas, J., Fletcher, A., Murphy, S., Melendez-Torres, G. J., Bonell, C., & Campbell, R. (2016). What is positive youth development and how might it reduce substance use and violence? A systematic review and synthesis of theoretical literature. BMC Public Health, 16(136), 135. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2817-3

Borden, L. M., Perkins, D. F., & Hawkey, K. (2014). 4-H youth development: The past, the present, and the future. Journal of Extension, 52(4). https://doi.org/10.34068/joe.52.04.35

Brestovansky, M., Sadovska, A., Kusy, P., Martincova, R., & Podmanicky, I. (2022). Development of prosocial moral reasoning in young adolescents and its relation to prosocial behavior and meaningfulness of life: Longitudinal study. Studia Psychologica, 64(3), 295–312. https://doi.org/10.31577/sp.2022.03.855

Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Pastorelli, C., Bandura, A., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2000). Prosocial foundations of children’s academic achievement. Psychological Science, 11(4), 302–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00260

Dahl, R. E., Allen, N. B., Wilbrecht, L., & Suleiman, A. B. (2018). Importance of investing in adolescence from a developmental science perspective. Nature (London), 554(7693), 441–450. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25770

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., & Pachan, M. (2010). A meta-analysis of after-school programs that seek to promote personal and social skills in children and adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45(3–4), 294–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-010-9300-6

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school- based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Farrington et al., 2012. Teaching adolescents to become learners: The role of noncognitive factors in shaping school performance: A critical literature review. (2012). In Teaching adolescents to become learners: The role of noncognitive factors in shaping school performance: A critical literature review. https://doi.org/info:doi/

Geldhof, G. J., Bowers, E. P., Mueller, M. K., Napolitano, C. M., Callina, K. S., & Lerner, R. M. (2014). Longitudinal analysis of a very short measure of positive youth development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(6), 933–949. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0093-z

Gootman, J. A., & Eccles, J. (2002). Community programs to promote youth development (1st ed.). National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10022

Greenberg, M. T. (2010). School-based prevention: current status and future challenges. Effective Education, 2(1), 27–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415531003616862

Hattie, J., & Jaeger, R. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning: A deductive approach. Assessment in Education : Principles, Policy & Practice, 5(1), 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969595980050107

Hurst, B., Wallace, R., & Nixon, S. B. (2013). The impact of social interaction on student learning. Reading Horizons, 52(4), 375.

Kirchhoff, E., Keller, R., & Blanc, B. (2024). Empowering young people-the impact of camp experiences on personal resources, well-being, and community building. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1348050–1348050. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1348050

Kiuru, N., Wang, M.-T., Salmela-Aro, K., Kannas, L., Ahonen, T., & Hirvonen, R. (2020). Associations between adolescents’ interpersonal relationships, school well-being, and academic achievement during educational transitions. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(5), 1057–1072. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01184-y

Larson, R. W. (2000). Toward a psychology of positive youth development. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 170–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.170

Lerner, R. M., & Overton, W. F. (2008). Exemplifying the integrations of the relational developmental system: Synthesizing theory, research, and application to promote positive development and social justice. Journal of Adolescent Research, 23(3), 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558408314385

Li, J., & Julian, M. M. (2012). Developmental relationships as the active ingredient: A unifying working hypothesis of “what works” across intervention settings. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82(2), 157–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01151.x

Luengo Kanacri, B. P., Eisenberg, N., Tramontano, C., Zuffiano, A., Caprara, M. G., Regner, E., Zhu, L., Pastorelli, C., & Caprara, G. V. (2021). Measuring prosocial behaviors: Psychometric properties and cross-national validation of the prosociality scale in five countries. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 693174–693174. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.693174

Mahoney, Joseph L. ; Larson, Reed W. ; Eccles, Jacquelynne S. (2005). Everybody’s gotta give: Development of initiative and teamwork within a youth program. In Organized Activities As Contexts of Development (pp. 171–196). Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410612748-14

Melendez-Torres, G. J., Dickson, K., Fletcher, A., Thomas, J., Hinds, K., Campbell, R., Murphy, S., & Bonell, C. (2016). Positive youth development programmes to reduce substance use in young people: Systematic review. The International Journal of Drug Policy, 36, 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.01.007

Moksnes, U. K., Eilertsen, M. B., Ringdal, R., Bjørnsen, H. N., & Rannestad, T. (2019). Life satisfaction in association with self‐efficacy and stressor experience in adolescents – self‐ efficacy as a potential moderator. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 33(1), 222–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12624

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). (2019). Applying lessons of optimal adolescent health to improve behavioral outcomes for youth: Public information-gathering session: proceedings of a workshop-in-brief. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Parker, P. D., & O’Neill, A. M. (2012). The influence of current mood on autobiographical memory retrieval. Memory, 20(7), 757–763. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2012.688291

Paulhus, D. L. (1991). CHAPTER 2 – Measurement and control of response bias. In Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes: Volume 1 of Measures of Social Psychological Attitudes (pp. 17–59). Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-590241-0.50006-X

Povilaitis, V., & Tamminen, K. A. (2018). Delivering positive youth development at a residential summer sport camp. Journal of Adolescent Research, 33(4), 470–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558417702478

Rhodes, J. E., Grossman, J. B., & Roffman, J. (2002). The rhetoric and reality of youth mentoring. New Directions for Youth Development, 2002(93), 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.23320029304

Roth, J. L., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2003). What exactly is a youth development program? Answers from research and practice. Applied Developmental Science, 7(2), 94–111. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532480XADS0702_6

Richards, K. A., & Levesque-Bristol, C. (2014). Developing teaching assistant self-efficacy through a pre semester teaching assistant orientation. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 85(S1), A153.

Scales, P. C., Roehlkepartain, E. C., & Shramko, M. (2017). Aligning youth development theory, measurement, and practice across cultures and contexts: Lessons from use of the developmental assets profile. Child Indicators Research, 10(4), 1145–1178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-016-9395-x

Shi, Y., & Moody, J. (2017). Most likely to succeed: Long-run returns to adolescent popularity. Social Currents, 4(1), 13–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329496516651642

Sibthorp, J., Paisley, K., Gookin, J., & Ward, P. (2007). Addressing response-shift bias: retrospective pretests in recreation research and evaluation. Journal of Leisure Research, 39(2), 295–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2007.11950109

Simpkins, S. D. (2015). When and how does participating in an organized after-school activity matter? Applied Developmental Science, 19(3), 121–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2015.1056344

Smith, C., Akiva, T., Sugar, S. A., Lo, Y. J., Frank, K. A., Peck, S. C., Cortina, K. S. & Devaney, T. (2012). Continuous quality improvement in afterschool settings: Impact findings from the Youth Program Quality Intervention study. Washington, DC: Forum for Youth Investment.

Sparr, M., Frazier, S., Morrison, C., Miller, K., & Bartko, W.T. (2020). Afterschool programs to improve social-emotional, behavioral, and physical health in middle childhood: A targeted review of the literature

Vijayakumar, N., Op de Macks, Z., Shirtcliff, E. A., & Pfeifer, J. H. (2018). Puberty and the human brain: Insights into adolescent development. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 92, 417–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.06.004

Warner, R. P., Sibthorp, J., Wilson, C., Browne, L. P., Barnett, S., Gillard, A., & Sorenson, J. (2021). Similarities and differences in summer camps: A mixed methods study of lasting outcomes and program elements. Children and Youth Services Review, 120, 105779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105779

Weissberg, R. P., Durlak, J. A., Domitrovich, C. E., & Gullotta, T. P. (Eds.). (2015). Social and emotional learning: Past, present, and future. In J. A. Durlak, C. E. Domitrovich, R. P. Weissberg, & T. P. Gullotta (Eds.), Handbook of social and emotional learning: Research and practice (pp. 3–19). The Guilford Press.

Wilson, C., Akiva, T., Sibthorp, J., & Browne, L. P. (2019). Fostering distinct and transferable learning via summer camp. Children and Youth Services Review, 98, 269–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.01.017

Zimmerman, B. J., & Kitsantas, A. (2005). Homework practices and academic achievement: The mediating role of self-efficacy and perceived responsibility beliefs. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 30(4), 397–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2005.05.003

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Self-efficacy: an essential motive to learn. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 82–91. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1016 Name of Candidate:Sarah Herring Date of Submission: April 23, 2025

Media Attributions

- 55776342_herring_sarah_range_submission