College of Humanities

49 Atrapadxs en un Hoyo: Reproductive Justice and Environmental Health of Latina Mothers and Children in Salt Lake City Utah

Jasmine Aguilar Lopez and Leandra Hernández

Faculty Mentor: Leandra Hernández (Communication, University of Utah)

A Senior Honors Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The University of Utah

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the

Honors Degree in Bachelor of Science

Abstract

This paper investigated Latina mothers’ perspectives of environmental health and reproductive justice, focusing on their understanding of their children’s health and well- being in Salt Lake County, Utah. The Great Salt Lake is a highly saline drying lake in Northern Utah and has become a large source of human-caused dust pollution. In addition to that, other factors such as refineries, seasonal inversions, redlining, and mining have exacerbated this pollution. Residents of Salt Lake City are experiencing adverse health effects due to their proximity to the lake and lack of information on how these impact nearby communities. During Fall 2024 and early 2025, I conducted a mixed-methods study which consisted of 51 completed surveys and 4 semi-structured interviews with women who live in near proximity of the lake and are mothers. The survey and interviews were conducted in Spanish. Participants reported perceiving their health as generally good; however, they acknowledged concerns about the drying Great Salt Lake and other environmental factors affecting their well-being. This study highlights a critical gap in environmental public health awareness among Latina mothers, emphasizing the urgent

need for targeted outreach and policy interventions to address their concerns.

Introduction

Asthma is one of the most common chronic conditions among children in the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), approximately 5.5 million children under the age of 18 currently have asthma (CDC, 2022). In 2022, Utah reported that 10.9% of adults and 7.2% of children were living with asthma (Utah Department of Health, 2022). Rates are disproportionately higher among children of racial and ethnic minorities, who are more likely to live in low-income neighborhoods located near highways, refineries, and industrial zones (Clark-Reyna et al., 2020). In these environments, exposure to air pollution and other environmental hazards significantly reduces quality of life, especially when compared to their white, middle-class counterparts (Morello-Frosch et al., 2011).

On the West Side of Salt Lake City, these disparities are stark. The area is home to a large Latinx population and has long experienced the effects of environmental racism, including proximity to polluting industries and limited access to green space and healthcare infrastructure (Wasatch Front Regional Council, 2021; Casey et al., 2017). Latina women—often mothers and caretakers—navigate a complex landscape where environmental health, reproductive justice, and family well-being intersect.

This research is deeply personal and rooted in my own family’s experience. It began with my mother’s frantic search for a new place to live. As a Latina woman, she encountered barriers that many in our community face when attempting to escape environmental hazards: limited housing options, discrimination, and economic constraints. Despite her best efforts, finding a safe and affordable home that was free from the harmful effects of air pollution and industrial proximity seemed nearly impossible. My mother, like many in our community, could feel the toll of living in an area heavily impacted by pollution. She often remarked that she could literally feel the smoke in her lungs, and this constant exposure made her worry about its long-term effects. She questioned whether the air quality had already impacted her health and the health of her children.

Her concerns mirrored those of many Latina mothers in neighborhoods on the West Side of Salt Lake City, where pollution levels are high, and access to clean air is limited. This personal experience served as a catalyst for exploring how environmental and reproductive justice intersect in communities like ours, and how these issues impact the health and well-being of Latina women and their families.

Environmental justice refers to the fair treatment of all people regardless of race, income, or nationality in the creation and enforcement of environmental laws (U.S. EPA, 2023). Reproductive justice, a framework developed by women of color, expands beyond access to reproductive healthcare to include the right to have children, not have children, and to parent children in safe and healthy environments (SisterSong, 2021; Ross, 2017). This study sits at the intersection of both frameworks.

This thesis explores how Latina women with children living on Salt Lake City’s West Side perceive environmental and reproductive justice as it relates to their health and well-being. Using a mixed-methods approach that integrates community-based interviews with public health and spatial data, the project aims to center the lived experiences of Latina mothers while contributing to broader conversations around justice, equity, and public health policy.’

Literature Review

In this literature review, I will explore the intersection of reproductive justice and environmental justice, specifically focusing on how environmental factors, such as air quality and geographic disparities, influence maternal and child health. I will begin by examining the concept of reproductive justice, particularly in the context of marginalized communities, before diving into the environmental hazards that disproportionately affect these populations. By connecting these two concepts, the review aims to highlight the systemic inequities that impact both the reproductive rights and overall well-being of racial and ethnic minority groups, with a particular focus on the challenges faced by mothers and children in these vulnerable communities.

Reproductive Justice

For this study, I define reproductive justice as “the state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, in all matters relating to the reproductive system and its functions and processes” (Onwuachi-Saunders et al., 2019). Additionally, I incorporate the perspective of In Our Own Voice: National Black Women’s Reproductive Agenda, which frames reproductive justice around three core pillars:

- The right to have children.

- The right not to have children.

- The right to nurture the children we have in safe and healthy environments.

This research focuses specifically on the third pillar, as it aligns with the concerns of mothers who witness the declining health of their children and themselves due to the social determinants of health (SDoH) they face.

The pressing issues is asthma, one of the most common chronic conditions among children in the U.S., is a key example of these health declines. In 2022, the state of Utah estimated that 10.9% of adults and 7.2% of children are suffering from asthma, with these rates being significantly higher among children from racial/ethnic minority groups. These children often live in poor neighborhoods near busy highways and industrial zones, which expose them to higher levels of environmental pollutants. When comparing these children to their white, middle-class counterparts, they experience a lower quality of life due to their increased exposure to environmental hazards, particularly in areas with compromised air quality (CDC, 2022; Morello-Frosch et al., 2011).

Environmental Justice

The concept of Environmental Justice, introduced by Robert Bullard in 1993, is defined as the basic human right to live, work, play, go to school, and worship in a clean and healthy environment. The United States Environmental Protection Agency expands on this, emphasizing the just treatment and meaningful involvement of all people in decision-making processes, regardless of income, race, color, national origin, Tribal affiliation, or disability (U.S. EPA, 2023). This literature review focuses on the intersection of environmental justice with geographical locations, air quality concerns, and the awareness of environmental risks, especially as they relate to children’s health in marginalized communities.

Geographical Disparities

Numerous studies highlight the close relationship between racial/ethnic minority children and low-income families residing in neighborhoods near industrial zones and busy highways (Grineski, 2021). The spatial distribution of health hazards often burdens Hispanic and African American populations with the greatest cumulative environmental exposures (Crowder & Downey, 2010). Utah mirrors this pattern, as studies show that the presence of the Mormon church has historically directed minority groups, including Latinx folk who live on the West Side of Salt Lake City, an area with higher levels of pollution and proximity to industrial sites (Faber, 2020). This geographic concentration exacerbates the challenges these communities face in maintaining their health.

Air Quality

Children in areas close to industrial zones, freeways, and other pollution sources are at an elevated risk of exposure to particulate matter, which can infiltrate the lungs and contribute to respiratory illnesses such as asthma. A study conducted in the Salton Sea region of California illustrates how dust storms from industrial sites increase the likelihood of respiratory crises in nearby communities (Johnston et al., 2019). Similarly, communities on the West Side of Salt Lake City, particularly those in proximity to the Great Salt Lake, experience poor air quality due to both local industrial emissions and environmental phenomena such as inversions, which trap pollutants in the valley for extended periods, further compromising air quality (Beard et al., 2012). The elevated levels of particulate matter (PM2.5) in these communities significantly contribute to respiratory health issues among children, further reinforcing the disparities in health outcomes (Lee et al., 2024).

Awareness of Environmental Risks to Children’s Health

Latina mothers often demonstrate a heightened awareness of environmental risks and their potential impacts on their children’s health. Studies have found that Latina mothers exhibit concern about the visible effects of pollution, with many proactively engaging in risk mitigation measures such as washing fruits and vegetables to reduce pesticide exposure and reducing tobacco smoke exposure in their homes (Evans, 2002). Despite these efforts, a sense of powerlessness persists among some mothers, stemming from the lack of autonomy they feel in controlling their exposure to environmental risks. This feeling of helplessness is especially poignant in communities like the West Side of Salt Lake City, where environmental hazards are difficult to avoid, and access to resources that might mitigate these risks is often limited (Kamai, 2023). Understanding these challenges is essential for addressing the needs of Latina mothers and designing interventions that both support their proactive efforts and address the systemic barriers they face in managing environmental health risks.

History of the West-Side

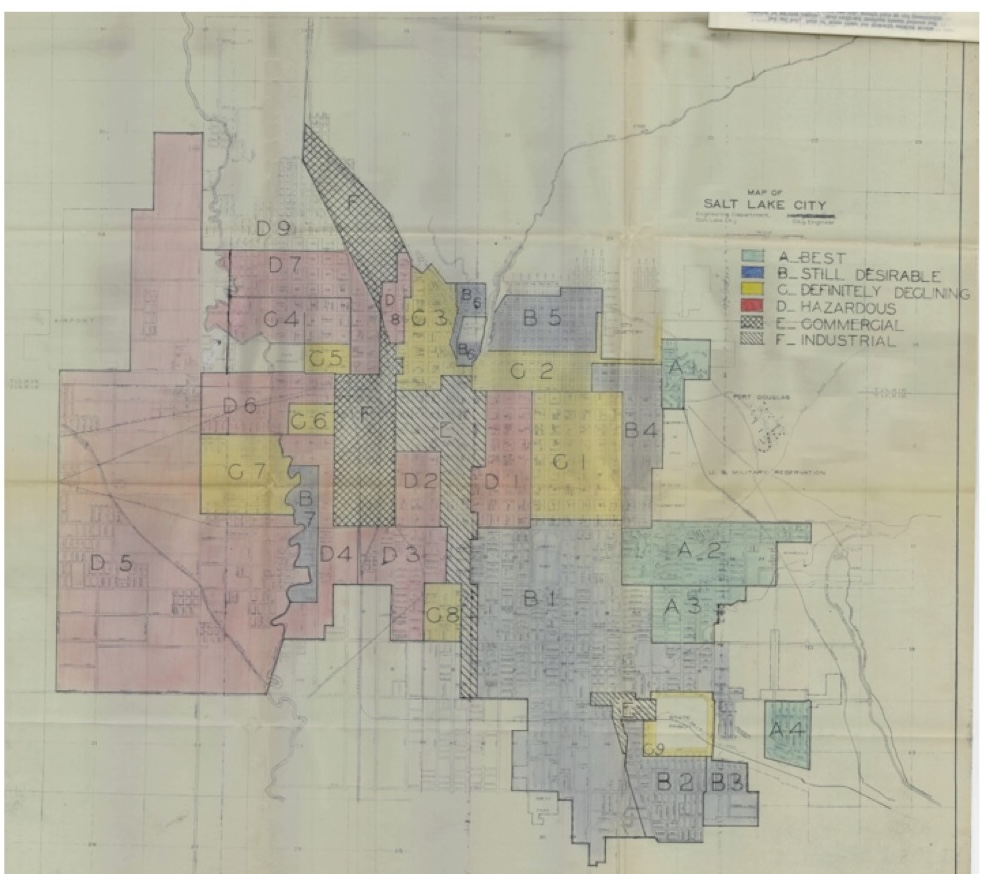

The geography of Salt Lake City was built upon environmental racism. After the Great Depression, the U.S. federal government introduced mortgage lending guidelines as part of the New Deal to stabilize housing markets across the country. Developed by the federal Homeowners Loan Corporation (HOLC), these guidelines took the form of redlining maps that categorized city districts based on factors such as proximity to industrial areas, housing conditions, average income, and racial demographics to assess the risk of mortgage defaults in various neighborhoods (Faber, 2020) including Salt Lake City.

This created a redlining map which designated areas with higher concentrations of pollution with residents of color who lived near industrial sites and were tied to the railroad industry, as “Hazardous” or “Definitely Declining.” On the contrary, predominantly white neighborhoods farther from industrial zones were labeled as “Still Desirable” or “Best.” (Table 1). Through these solidified city plans, it restricted Black and Latinx residents to own/rent properties in areas of town with more pollution.

Figure 1 – Home Owners Loan Corporation Redlining Map 1938

From 1860-1950, Salt Lake City was 99% white but since then has had a growing population of people than just the white alone. Utah’s first historic Latine communities comprised of Mexican immigrants that came due to the expansion of the railroads (Mayer et al., 1973) thus becoming a crucial part of Utah’s economy via work on railroads, mines, livestock, and agriculture. Due to the Latine population’s jobs being in areas around Pioneer Park and on the West Side of Salt Lake City in the 1930s, redlining continued perpetuate neighborhood divide. Today, Latine-identifying individuals make up 20.8% of Salt Lake City’s population, making them the second-largest demographic group after white residents, who account for 70.5% (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023). Latine communities remain predominantly concentrated on the west side of the city, with Interstate-15 serving as a dividing line between Latine and white populations.

Inversion and Air Quality

In December 2024, Salt Lake City experienced an unusual inversion, a weather phenomenon that has significant implications for air quality and public health. Inversions occur during winter when a layer of cold air, along with trapped pollution, becomes confined beneath a warmer air layer that acts as a lid, effectively reversing typical atmospheric conditions (Utah Department of Environmental Quality, 2024). These Utah inversions are often triggered by snowstorms, as the colder air settles near the surface. Geographic features, such as Salt Lake City’s Wasatch Mountain Range, can amplify the severity of inversions by shielding the valley from wind that might otherwise disperse pollutants.

Inversions play a significant role in air quality along the Wasatch Front. The combination of current pollution levels, vehicle emissions, industrial pollutants, and other local sources contributes to the trapping of pollutants, which significantly increases PM2.5 concentrations. These inversions can persist for days and often occur multiple times during the winter season, leading to prolonged exposure to poor air quality (Beard et al., 2012). A study conducted in Oman found that the frequency and intensity of inversions were associated with an increase in daily emergency hospital visits for four conditions (Abdul-Wahab, 2005). Additionally, Wallace et al. (2010) studied 674 people with asthma in Hamilton, Ontario, comparing their health on inversion days versus non- inversion days. They found that, during inversion days, there was a significant increase in certain immune cells in patients’ sputum, which indicates airway inflammation. Specifically, neutrophil and macrophage counts were higher on inversion days, but the study did not find a direct link between this inflammation and specific pollutants. Such events are more than weather phenomena; they are public health crises. Families living in historically neglected areas suffer the worst impacts, illustrating once again how environmental degradation and reproductive justice are deeply entwined.

Terminal Lakes

On the west side of Salt Lake City lies the Great Salt Lake (GSL), a terminal lake. Terminal lakes, also known as inland seas or saline lakes, are fed by rivers but lack outlets. As of 2023, the GSL has lost 73% of its water volume and 60% of its surface area (Abbott et al., 2023). This depletion is primarily driven by water diversions for agricultural, industrial, and municipal uses, as well as the needs of local ecosystems, such as bird species dependent on brine shrimp found in the lake. Additionally, reduced streamflow and climate change have exacerbated its decline (Wurtsbaugh et al., 2020). If water levels do not recover, long-term projections suggest significant adverse effects on the lake’s ecosystem and regional climate (Cohen, 2014).

As the GSL continues to shrink, it is becoming a major source of dust emissions, contributing to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) air pollution and posing health risks to surrounding communities. For instance, at California’s Salton Sea, a one-foot drop in water levels resulted in a 2.6% increase in PM2.5 levels in nearby areas (Jones and Fleck, 2020). Wind-driven dust storms from the drying Salton Sea have already led to significant air quality deterioration in adjacent communities (Johnston et al., 2019). A similar pattern could unfold with the continued desiccation of the GSL. PM2.5 is a major environmental health hazard, as it is the leading environmental cause of mortality worldwide and is responsible for premature deaths in the United States.

The literature reviewed thus far illustrates the complex interplay between environmental justice and reproductive justice, particularly in marginalized communities. From the historical legacy of redlining and its long-term effects on community health, to the contemporary environmental hazards posed by air quality, inversions, and the degradation of terminal lakes, the evidence points to the profound health risks faced by racial and ethnic minority populations, particularly children. As these factors directly influence reproductive health and maternal well-being, the need for systemic interventions becomes clear.

This review also underscores the critical role of community awareness and agency in mitigating these risks, particularly among Latina mothers who take proactive steps to protect their children. However, the barriers to fully addressing environmental injustices are evident, as many of these mothers experience a sense of powerlessness in controlling their exposure to harmful environmental factors. In the following section, I will describe the methods employed in this study to further explore these issues. Through a combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches, the study aims to assess the real- world impact of environmental health risks this population.

Methods

The complete study was carried out from November 2024 to February 2025. Prior

to the start of the research, I obtained human subjects approval from the University of Utah Institutional Review Board. All participants were provided with electronic consent forms prior to the start of the data collection. During the interviews, participants were reminded about their rights to withdraw, and the electronic consent form was brought up once again.

Participant Recruitment

To recruit participants for this study, I employed convenience (non-randomized) sampling in combination with snowball sampling. Snowball sampling proved especially effective, as it allowed me to distribute a Qualtrics survey through my personal social media platforms, including Instagram and Facebook. The survey was initially launched in mid-November and remained open through late January. However, this first round of data collection was compromised by false responses and the presence of bot activity, rendering the data unusable. Consequently, the survey was reopened in early February, and data collection concluded by mid-February, once enough valid responses had been obtained.

To broaden its reach, the survey was shared in multiple Facebook community groups, such as Mexicanas en Utah & Amigas, *Mexicanas Viviendo En Utah VIP, and Mamas Latinas en Utah!. It was also posted in additional local groups using keywords like “Latina,” “Mamas/Mothers,” and specific city names associated with the West Side of Salt Lake City. This strategy created a true snowball effect, allowing the survey to be widely circulated and enhancing participant recruitment.

At the end of the survey, respondents were given the opportunity to volunteer for a follow-up interview. To be eligible for the study, participants had to meet the following criteria: (1) identify as Latina (defined as a person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin, regardless of race); (2) be 18 years of age or older; (3) be currently pregnant or have children living in the home; and (4) reside on the West Side of Salt Lake City.

Qualitative and Sociodemographic Survey Data Collection

Between January 2025 and February 2025, I conducted 4 interviews, all which were conducted in Spanish. I followed recommendations for obtaining data saturation for interviews. A semi-structured interview guide was used for the interviews. These interviews were conducted via Teams video conferencing; however, if the participants were not able to access Teams, they could opt to participate in the research via voice messages on Facebook’s Messenger. Interviews approximately lasted 30-60 minutes each. All these were audio recorded and then transcribed. Participants were selected from the Qualtrics survey based on their expressed interest in an interview. They completed a brief sociodemographic survey during both the survey and interview process to confirm eligibility. Participants received a $10 gift card in appreciation of their time and sharing their experiences.

Data Analysis

The textual data from the interviews were analyzed as one dataset. A rapid analytic approach using summary templates was used to analyze the textual data. I would read each transcript line by line and interpret this as qualitative data. A matrix was then created where I further condensed and simplified the data from each template into a matrix. This approach allowed for me to organize the textual data and compare the content across other interviewees. Below I will describe the themes that evolved from the analysis.

Results

Participant Characteristics

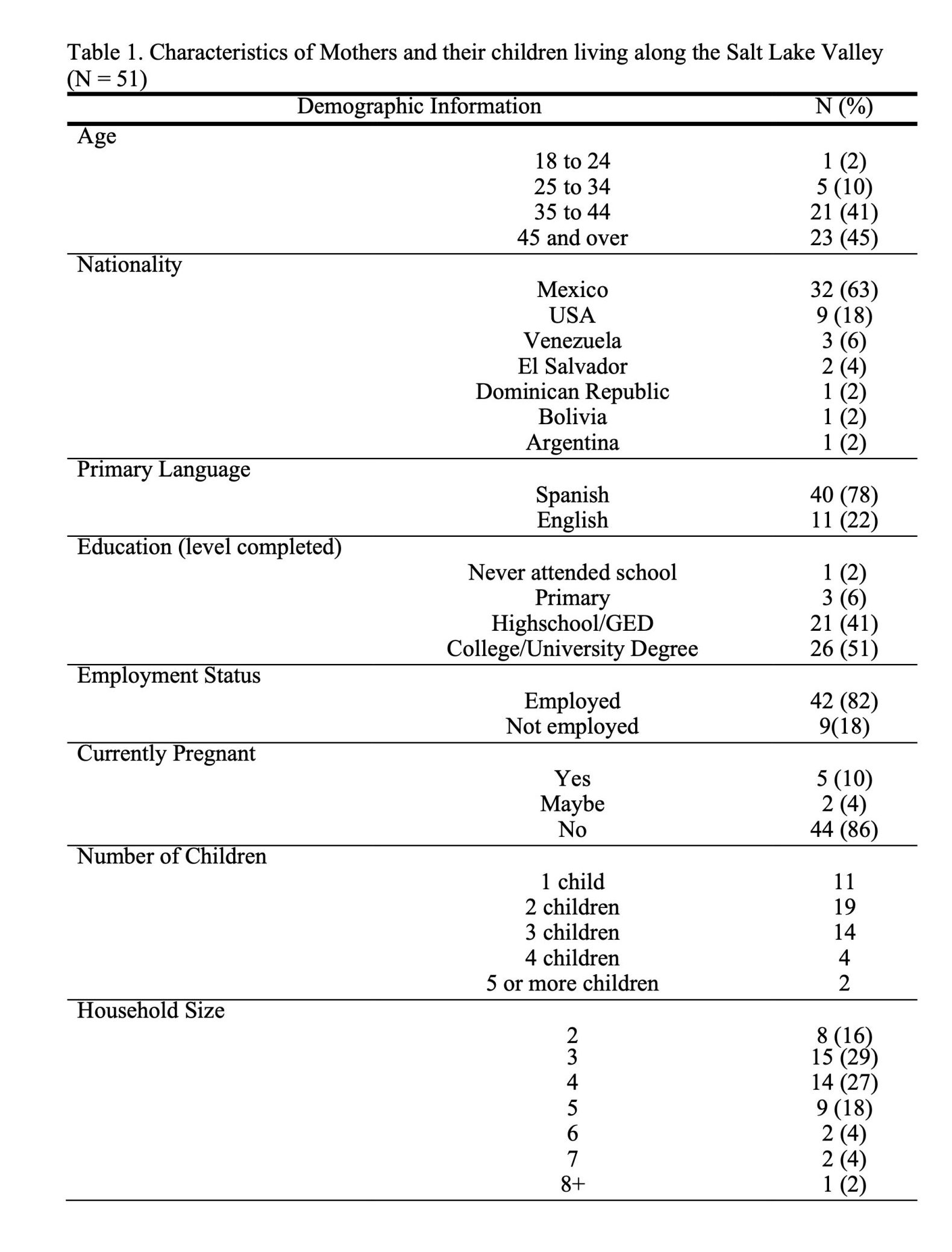

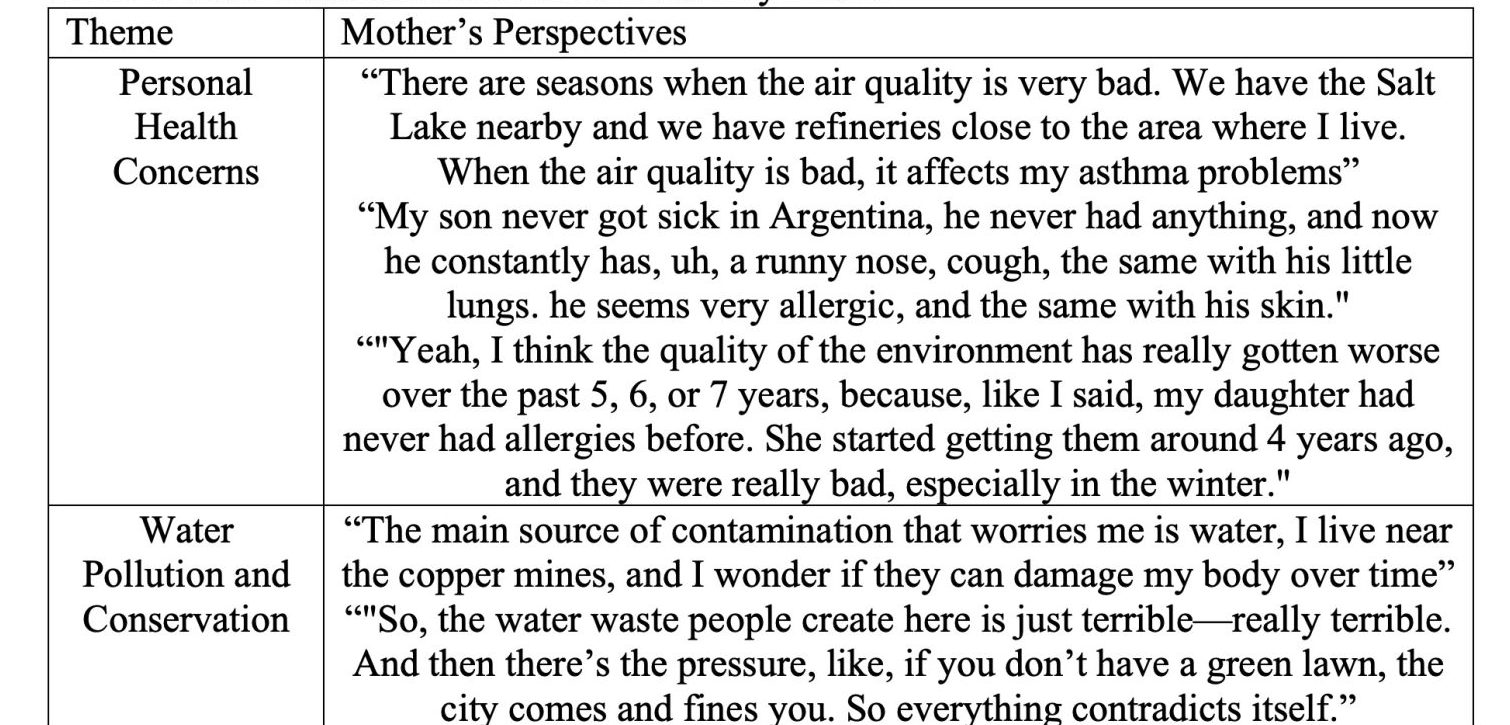

A total of 51 Latina Mothers participated in the Qualtrics survey section of the study. All mothers had to had lived on the West-side of Salt Lake City for at least a year. As indicated in Table 1, most of the mothers were from Mexico or other countries including United States of America, Venezuela, El Salvador, Dominican Republic, Bolivia, and Honduras. The participants’ ages ranged from the youngest being 21, the oldest being 67, and the mean age for this population is 42.7. The average amount of children these women was 2.37 kids with the low being 1 kid and the high being 5 kids.

Table 1. Characteristics of Mothers and their children living along the Salt Lake Valley (N = 51)

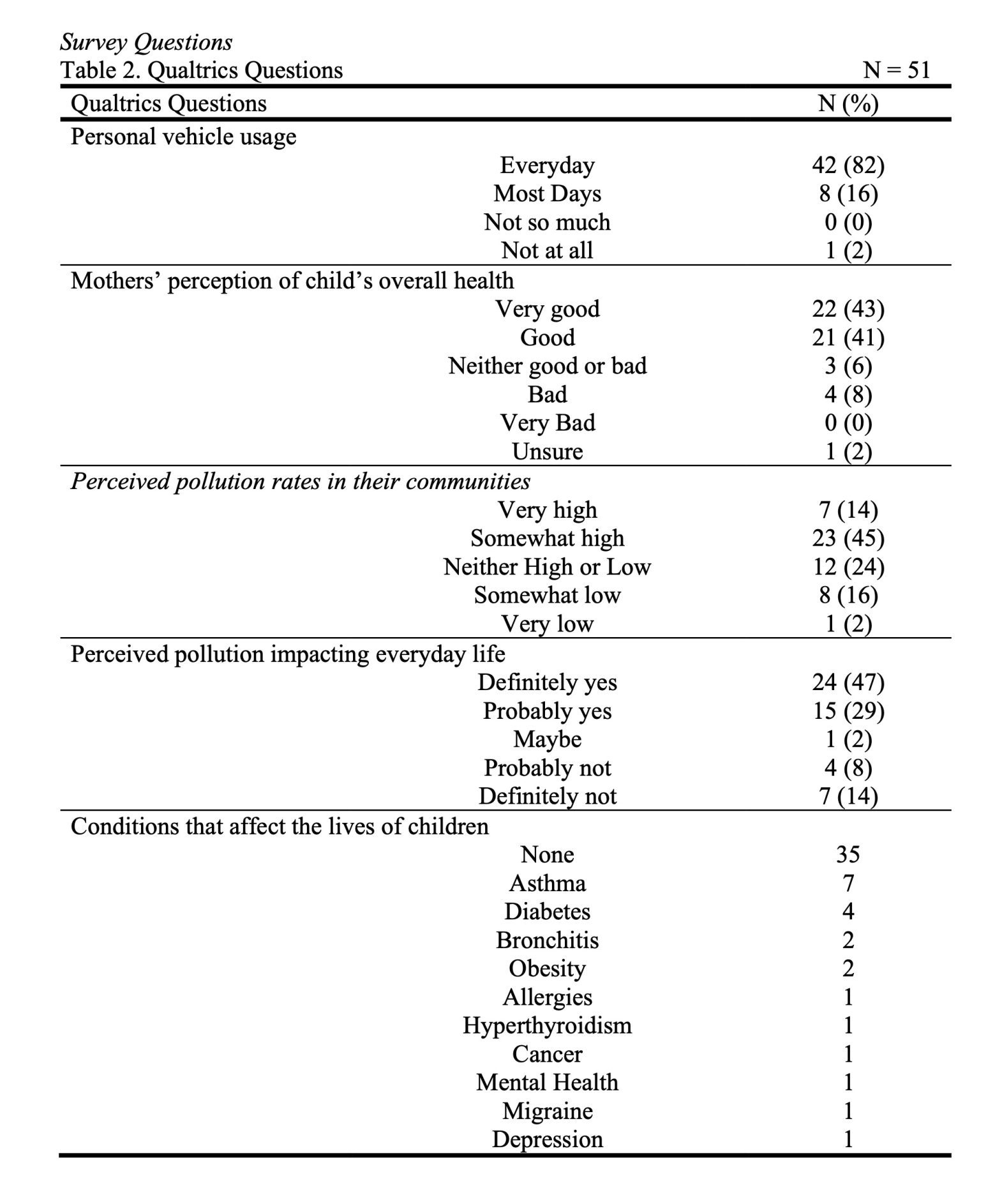

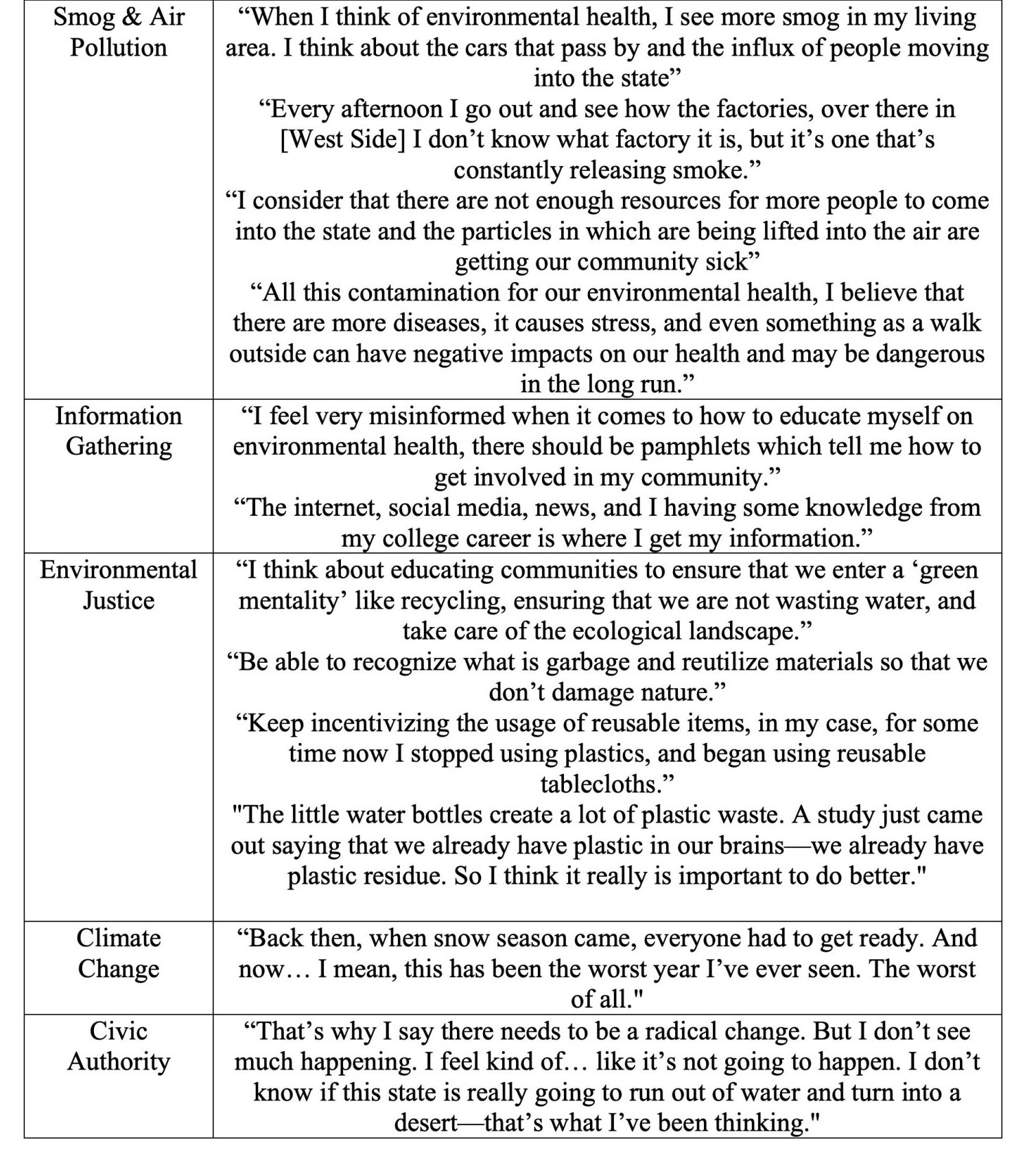

In the quantitative section of the Qualtrics survey (Table 2), participants generally described their children’s health as good. When asked, ‘How would you describe the overall health of your child(ren)?’ 43% of respondents rated it as very good, 41% as good, 6% as neither good nor bad, 8% as bad, and 2% were unsure. Regarding daily transportation habits, 42 out of 51 women reported needing to use their cars daily, while 8 said they used them most days. When asked, ‘What conditions impact the lives of your child(ren)?’ most participants reported none. However, 7 women mentioned asthma, 4 cited diabetes, 2 noted obesity and bronchitis, and 1 reported allergy, hyperthyroidism, cancer, mental health issues, migraines, and depression.

Despite these generally positive health assessments, perceptions of pollution levels were concerning. When asked, ‘How high is the pollution rate in your community?’ 14% rated it very high, 45% somewhat high, 24% neither high nor low, 16% somewhat low, and 2% very low. Additionally, when asked whether pollution impacts their daily lives, 47% responded ‘definitely yes,’ 29% said ‘probably yes,’ 2% said ‘maybe,’ 8% said ‘probably not,’ and 14% answered ‘definitely not.’ While participants reported relatively good health outcomes for their children, their perceptions of pollution remained high, with many acknowledging its significant impact on their daily lives.

Table 2. Qualtrics Questions Qualtrics Questions Personal vehicle usage

Understanding of the Intersection Between Health and Environment

When it came to asking about, “On a scale from 1 – 5 (1 being not so much and 5 being very much) how well do you understand the intersection between the environment and your health?” the mean answer was 3.76 out of 5.

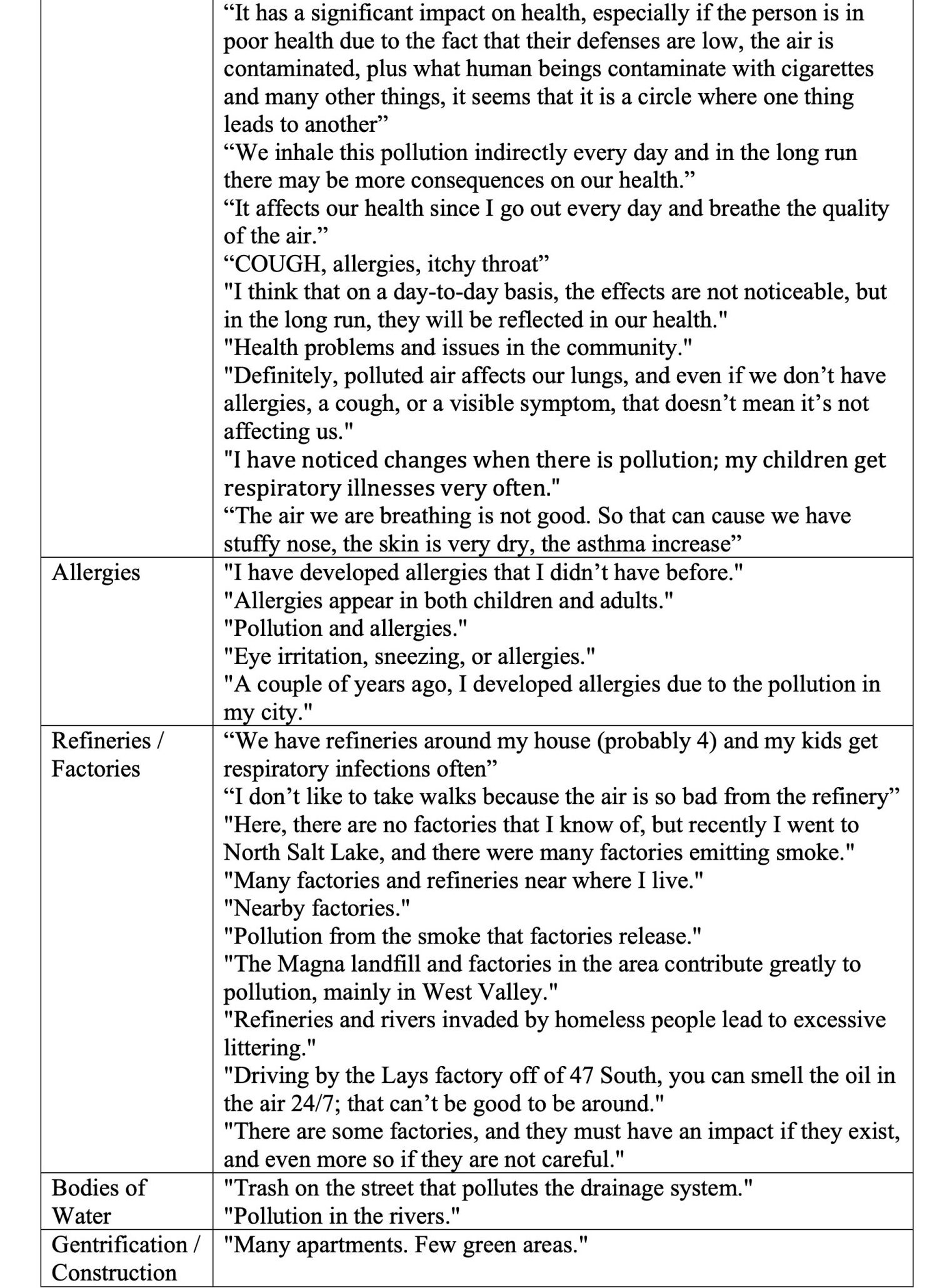

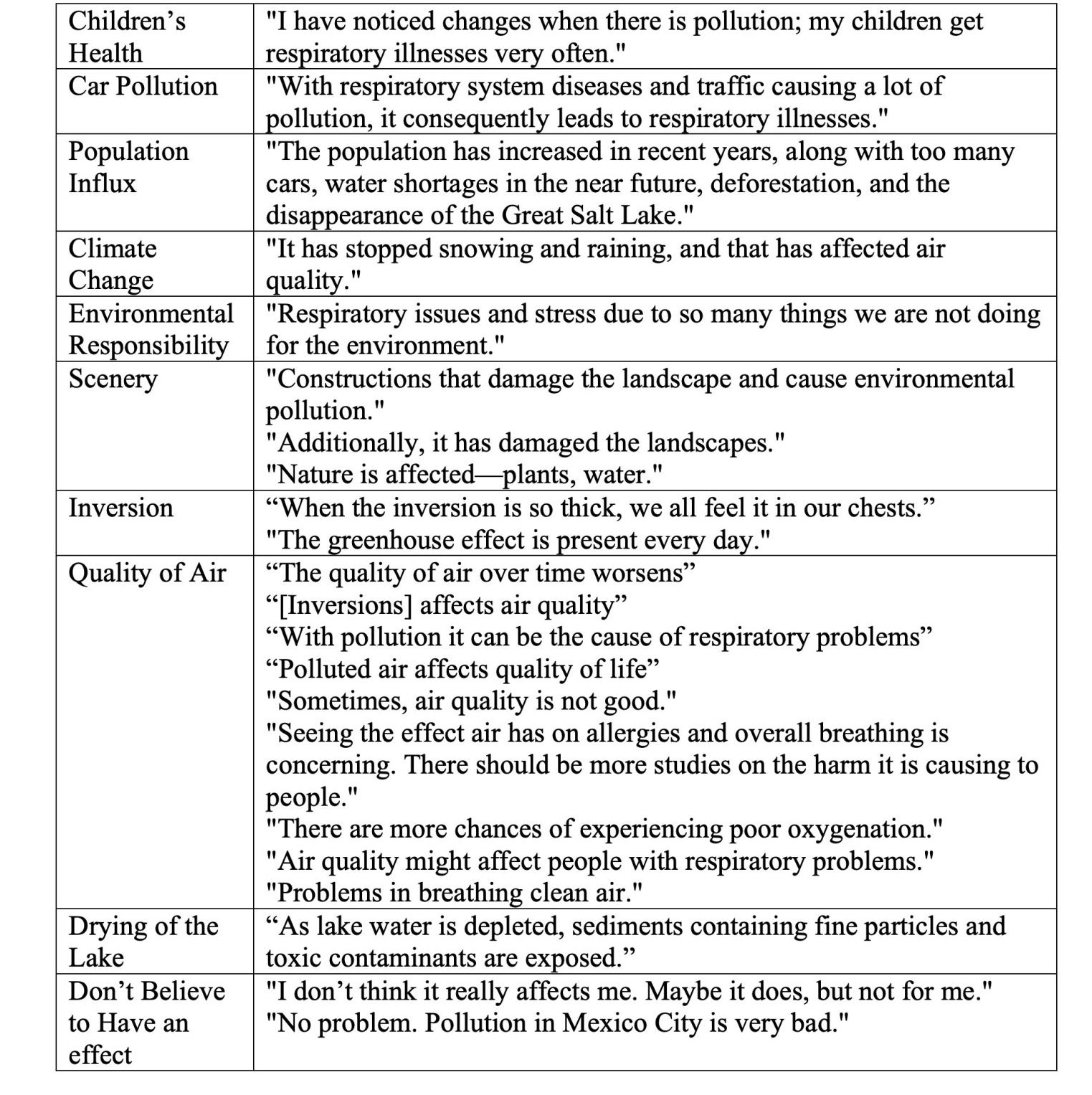

Ways in Which Pollution Impacts Their Everyday Lives

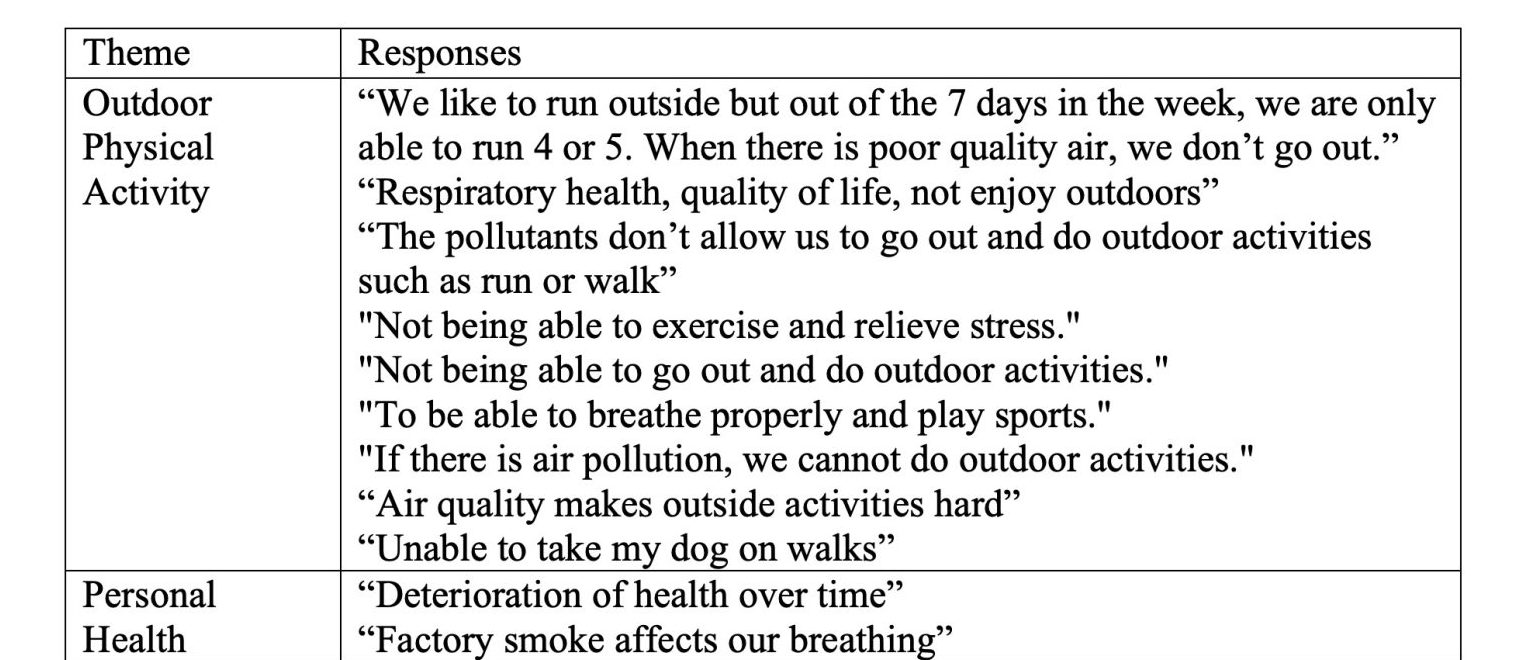

The Qualtrics study reveals the significant impact of pollution on various aspects of daily life in the Salt Lake Valley. To gain deeper insight, participants were encouraged to share their experiences and perceptions of how pollution affects their everyday lives. In response to the question, “How or in what way does pollution impact your everyday life (e.g., health issues, nearby factories affecting the scenery)?”, several recurring themes emerged, including limitations on outdoor physical activity, personal health concerns, and broader environmental issues, as outlined in Table 3.

Table 3. Perceived Impact of Pollution on Daily Life in the Salt Lake Valley (Qualtrics Study)

Outdoor Physical Activity

Many participants expressed that air pollution restricts their ability to engage in outdoor activities such as running, walking, and exercising. As one respondent noted, “We like to run outside but out of the 7 days in the week, we are only able to run 4 or 5. When there is poor quality air, we don’t go out.” Other participants echoed similar frustrations, mentioning that poor air quality prevents them from walking their pets or enjoying outdoor recreation. These responses illustrate how pollution directly impacts daily routines and physical well-being.

Personal Health and Respiratory Issues

Concerns about pollution’s impact on health emerged as a dominant theme. Many participants described experiencing respiratory issues, with statements such as “Factory smoke affects our breathing” and “We inhale this pollution indirectly every day and in the long run there may be more consequences on our health.” Symptoms such as coughing, allergies, itchy throat, and increased asthma occurrences were frequently reported, reinforcing existing research that links air pollution to long-term health consequences. Some participants also expressed concerns about the cumulative effects of pollution, suggesting that while the impact may not always be immediately noticeable, it could have serious implications over time.

Allergies and Increased Sensitivities

Another common theme was the connection between pollution and allergies. Several participants noted that they had developed allergies they had never experienced before, with responses such as “I have developed allergies that I didn’t have before” and “Pollution and allergies.” Others mentioned symptoms such as eye irritation and sneezing, linking these directly to pollution exposure. These responses suggest that even individuals without preexisting conditions are noticing changes in their health due to environmental factors.

Industrial Pollution and Environmental Concerns

Many respondents pointed to industrial pollution as a major contributor to poor air quality in their communities. Concerns about nearby refineries and factories frequently

emerged, with one participant stating, “We have refineries around my house (probably 4), and my kids get respiratory infections often.” Others described the strong presence of pollutants in specific areas, such as “Driving by the Lays factory off of 47 South, you can smell the oil in the air 24/7; that can’t be good to be around.” Additionally, concerns about excessive littering, landfill waste, and vehicle emissions were raised, further illustrating the multifaceted nature of pollution in the region.

Air Quality and Community Well-Being

The perception of pollution’s impact was overwhelmingly negative, with many participants emphasizing how it affects their quality of life. The statement “Polluted air affects quality of life” was commonly echoed, and some participants specifically mentioned how inversions worsen air conditions. One respondent observed, “When the inversion is so thick, we all feel it in our chests,” highlighting the immediate and tangible effects of pollution on respiratory health.

Table 4. Semi-Structured Interviews Main Key Points Theme Mother’s Perspectives

The semi-structured interviews revealed six prominent themes regarding environmental health concerns among mothers: personal health concerns, water pollution and conservation, smog and air pollution, information gathering, environmental justice, and civic authority. These themes reflect a growing sense of vulnerability and a call for systemic change in response to worsening environmental conditions.

Personal Health Concerns

Mothers expressed deep concern for the health of their children and themselves, often connecting respiratory and skin-related illnesses to environmental degradation. One participant noted, “My son never got sick in Argentina… now he constantly has a runny nose, cough…” Similarly, others described the onset of new allergies and asthma flare- ups correlating with worsening air quality. Seasonal changes and proximity to industrial zones like refineries and the Salt Lake were frequently mentioned as exacerbating factors.

Water Pollution and Conservation

Water quality emerged as a critical concern, especially for those living near industrial sites like copper mines. Participants voiced unease about long-term health effects, stating, “I wonder if they can damage my body over time.” Additionally, there was frustration over local ordinances that conflict with conservation efforts, particularly regarding water usage for lawns, illustrating a disconnect between policy and sustainable living.

Smog and Air Pollution

Smog and airborne pollutants were frequently cited as visible and immediate threats. Mothers discussed the growing number of vehicles, population influx, and local factory emissions. One stated, “There are not enough resources for more people… the particles being lifted into the air are getting our community sick.” This theme was also tied to increased stress and concern over long-term community health outcomes.

Information Gathering

A common thread among participants was a lack of accessible, clear information about environmental health. While some relied on internet sources or personal education, others felt misinformed and unsupported. One participant shared, “There should be pamphlets which tell me how to get involved in my community.”

Environmental Justice

Participants showed a strong desire to take part in environmental stewardship but highlighted the need for collective action and education. Many had adopted practices like using reusable items or recycling but emphasized that broader community awareness is necessary. One mother remarked, “We already have plastic in our brains… So I think it really is important to do better.”

Climate Change and Civic Authority

Concerns about climate change were voiced in relation to shifting seasons and diminishing snowfall. Moreover, there was a pervasive sense of powerlessness regarding civic leadership and state-level responses to environmental degradation. One participant reflected, “I feel kind of… like it’s not going to happen. I don’t know if this state is really going to run out of water and turn into a desert.”

Across all themes, mothers reported a general sense of maintaining personal and family health but also recognized the growing threats posed by their environmental conditions. Although many take proactive steps, such as conserving water or reducing plastic use, these efforts often feel inadequate in the face of rising pollution and insufficient systemic support. A recurring sentiment was one of helplessness, participants feel unequipped, underinformed, and lacking the institutional backing needed to drive meaningful change. This aligns with findings from Kamai (2023), highlighting the limited empowerment mothers feel in addressing health issues rooted in environmental injustice.

Discussion

My study aimed to explore Latina women’s perceptions of the connection between environmental and reproductive justice and its impact on their own health, well-being, and that of their children as residents of Salt Lake City’s west side. Individuals in low- income and minority communities, such as Latina mothers in our study, are disproportionately exposed to high levels of pollution (Grineski, 2021). This reflects broader environmental justice concerns, as these populations often face systemic barriers to advocacy and intervention. The environmental hazards near the Great Salt Lake exemplify “slow violence” a gradual, cumulative harm to marginalized communities with little immediate attention or policy response (Nixon, 2013).

My findings have critical public health implications for residents of the West Side of Salt Lake City. Exposure to pollution may contribute to increased asthma rates, higher stress levels, and reduced opportunities for physical activity due to poor air quality. Beyond the local context, these issues extend globally, as the drying of saline lakes and rising emissions exacerbate health disparities and climate change-related risks.

It is crucial that policymakers and global health organizations recognize these harms and take proactive measures. One challenge is “label avoidance” a phenomenon where individuals refrain from acknowledging symptoms to avoid the stigma or consequences associated with a diagnosis (Hsieh & Kramer, 2021). Addressing this requires community-driven efforts to empower marginalized groups to voice their concerns.

Future initiatives should explore partnerships with advocacy organizations to create community events and resources that amplify these voices and drive policy change. Without intervention, vulnerable populations will continue to bear the brunt of environmental injustices, worsening health disparities in the long term.

Limitations

This study provides insights into the lived experiences of Latina mothers and their children in the Salt Lake area. However, several limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, survey fatigue may have affected participant engagement. Since the survey was distributed through social media, participants may have been more inclined to resume scrolling or may have been interrupted by other responsibilities, particularly as busy mothers. Secondly, I merged one-on-one interview data with that of a focus group data to accommodate the needs of study participants time and my availability as well. I also found that when using one-on-one interviews, they gave the participants individual level experiences and perspectives, whereas focus group interviews gave me shared collective experiences or experiences of a community. Thirdly, this study does not capture the perspectives of all Latin American demographics in Salt Lake, Davis, and Utah Counties. With Mexican representation being the majority, I would have preferred to place greater emphasis on other nationalities, such as Venezuelans, Peruvians, and Colombians, as Utah’s Latin American population continues to grow in diversity. Lastly, aside from capturing the Latine community, I do recognize that it doesn’t capture the entirety of the West-side population. I chose not to include other demographic populations such as but not limited to White, Black, Asian, and American Indian, because I wanted to focus on my own community as well as my lived experience. Through my study, I observed that various Facebook groups reflected distinct cultural differences, which also required expanding the geographic scope to include different cities. Regardless, the participants showed eagerness and wanted a more studies like this to be conducted.

Conclusions

This study has important public health implications for Latinx mothers, their children, and the broader community. As mentioned previously, I do recognize that there is a gap and that not everyone on the West-side of Salt Lake City is being represented in this research. This leaves space for more research to be conducted including the population not investigated in this research. The case of the Salt Lake Area and its effects on the children and families living the area offers a preview into what is to come in the upcoming decades. As climate change progresses, experts in the fields of environmental justice and global health organizations anticipate significant increases in global emissions and air pollutants due to climate change’s contribution to poor air quality and subsequent increases in asthma and related respiratory conditions. Without any sort of intervention, Latinx individuals on the West-side can continue to experience poor health outcomes if these trends continue. More work must be done to involve individuals who are currently experiencing this and give them power to advocate for their communities.

Acknowledgements

I extend my deepest gratitude to Leandra H. Hernandez, PhD, for her invaluable guidance and mentorship throughout this research. I also sincerely appreciate the support provided by the Office of Undergraduate Studies and The Wilkes Center for Climate Science and Policy, whose educational and financial assistance made this work possible. Additionally, I am grateful to the Communication Department and the College of Humanities at the University of Utah for their generous travel support, which enabled me to present this honors thesis at the 95th Western States Communication Association Convention in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Additionally, an honorable mention to Robin Jensen, PhD for her support from afar. Through this project and support of my professors, without them, I wouldn’t have made it as far as receiving the Outstanding Undergraduate Researcher Award 2025 for the College of Humanities, I am so grateful for all those that have let me into their lives and believed in my why.

Bibliography

Abbott BW, Baxter BK, Busche K, de Freitas L, Frie R, Gomez T, et al. . 2023. Emergency Measures Needed to Rescue Great Salt Lake from Ongoing Collapse. https://pws.byu.edu/great-salt-lake

Abdul-Wahab, S. A., Bakheit, C. S., & Siddiqui, R. A. (2005). Study the relationship between the health effects and characterization of thermal inversions in the Sultanate of Oman. Atmospheric Environment (1994), 39(30), 5466–5471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2005.05.038

Beard, J. D., Beck, C., Graham, R., Packham, S. C., Traphagan, M., Giles, R. T., & Morgan, J. G. (2012). Winter temperature inversions and emergency department visits for asthma in Salt Lake County, Utah, 2003-2008. Environmental health perspectives, 120(10), 1385–1390. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1104349

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Most recent asthma data. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_data.htm

Clark-Reyna, S. E., Grineski, S. E., & Collins, T. W. (2020). Racial/ethnic disparities in asthma hospitalization in the USA: A national level study. Population Health, 12, 100658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100658

Cohen, M. J., (2014) Hazard’s Toll: The costs of inaction at the salton sea. Pacifc Institute. https://pacinst.org/publication/hazards-toll/#:~:text=It%20finds%20that %20worsening%20air,plan%20at%20the%20time%20of

Crowder, K., & Downey, L. (2010). Interneighborhood Migration, Race, and Environmental Hazards: Modeling Microlevel Processes of Environmental Inequality. American Journal of Sociology, 115(4), 1110–1149. https://doi.org/10.1086/649576

Faber, J. W. (2020). We Built This: Consequences of New Deal Era Intervention in America’s Racial Geography. American Sociological Review, 85(5), 739–775. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122420948464

Forno, E., & Celedon, J. C. (2009). Asthma and ethnic minorities: socioeconomic status And beyond. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology, 9(2), 154–160. https://doi.org/10.1097/aci.0b013e3283292207

Grineski, S., Collins, T., Renteria, R., & Rubio, R. (2021). Multigenerational immigrant trajectories and children’s unequal exposure to fine particulate matter in the US. Social science & medicine (1982), 282, 114108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114108

Hassan, D., Burian, S. J., Johnson, R. C., Shin, S., & Barber, M. E. (2023). The Great Salt Lake Water Level is Becoming Less Resilient to Climate Change. Water Resources Management, 37(6-7), 2697-2720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-022- 03376-x

Hsieh, E., & Kramer, E. M. (2021). Rethinking culture in health communication: Social Interactions as intercultural encounters. Wiley Blackwell.

Johnston, J. E., Razafy, M., Lugo, H., Olmedo, L., & Farzan, S. F. (2019). The Disappearing Salton Sea: A critical reflection on the emerging environmental threat of disappearing saline lakes and potential impacts on children’s health. The Science of the total environment, 663, 804–817.https://doi.org/10.1016 /j.scitotenv.2019.01.365

Jones, B. A., & Fleck, J. (2020). Shrinking lakes, air pollution, and human health: Evidence from California’s Salton Sea. The Science of the total environment, 712, 136490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136490

Kamai, E.M., Calderon, A., Van Horne, Y.O. et al. Perceptions and experiences of environmental health and risks among Latina mothers in urban Los Angeles, California, USA. Environ Health 22, 8 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940- 023-00963-2

Lee, L. Y., Kerry, R., Ingram, B., Golden, C. S., & LeMonte, J. J. (2024). Investigating the Spatial Patterns of Heavy Metals in Topsoil and Asthma in the Western Salt Lake Valley, Utah. Environments, 11(10), 223.https://doi.org/10.3390 /environments11100223

Mayer, V. V., Morgan, P., Nelson, A., & Coronado, G. (1973). Working papers toward a History of the Spanish-speaking people of Utah: A report of research of the Mexican-American Documentation Project | American West Center Research Projects. https://collections.lib.utah.edu/details?id=1396789

Morello-Frosch, R., Pastor, M., Sadd, J. L., & Shonkoff, S. B. (2011). The climate gap: Environmental health and equity implications of climate change and mitigation policies in California—a review of the literature. Climatic Change, 109(S1), 485– 503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-011-0310-7

Nelson, R. K., Ayers, N., Madron, J., & the Digital Scholarship Lab. (n.d.). Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America – Salt Lake City, Utah. University of Richmond. https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/map/UT/SaltLakeCity/c ontext#loc=12/40.7547/-111.8948

Nixon, R. (2011). Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt2jbsgw

Onwuachi-Saunders, C., Dang, Q. P., & Murray, J. (2019). Reproductive Rights, Reproductive Justice: Redefining Challenges to Create Optimal Health for All Women. Journal of healthcare, science and the humanities, 9(1), 19–31.

Oraka, E., Iqbal, S., Flanders, W. D., Brinker, K., & Garbe, P. (2013). Racial and ethnic disparities in current asthma and emergency department visits: Findings from the National Health Interview Survey, 2001-2010. Journal of Asthma, 50(5), 488-496. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2013.790417

Pulido, L. (2000). Rethinking Environmental Racism: White Privilege and Urban Development in Southern California. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 90(1), 12–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/0004-5608.00182

Pulido, L. (2017). Geographies of race and ethnicity II: Environmental racism, racial capitalism and state-sanctioned violence. Progress in Human Geography, 41(4), 524–533. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516646495

In Our Own Voice: National Black Women’s Reproductive Justice Agenda. (n.d.). Reproductive Justice. https://blackrj.org/our-causes/reproductive-justice/

Ross, L. J., & Solinger, R. (2017). Reproductive Justice: An Introduction (1st ed.). University of California Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctv1wxsth

SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective. (2021). What is Reproductive Justice? https://www.sistersong.net/reproductive-justice U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). (2023). Environmental justice. https://www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice

Utah Department of Environmental Quality. (2024). Inversions. from https://deq.utah.gov/air-quality/inversions

Utah Department of Health. (2022). Utah Asthma Program Annual Report 2022. https://health.utah.gov/asthma

U.S. Census Bureau quickfacts: Salt Lake City City, UtahQuickFacts Salt Lake City city, Utah. United States Census Bureau. (n.d.). https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/saltlakecitycityutah/PST045223

Wallace, J., Nair, P., & Kanaroglou, P. (2010). Atmospheric remote sensing to detect effects of temperature inversions on sputum cell counts in airway diseases. Environmental research, 110(6), 624–632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2010.05.011

Wasatch Front Regional Council. (2021). Equity in the built environment: Salt Lake County profile. https://wfrc.org/community/equity

World Population Review. (2025). Salt Lake City, Utah population 2024. https://worldpopulationreview.com/us-cities/utah/salt-lake-city

Wurtsbaugh, W. A., Leavitt, P. R., & Moser, K. A. (2020). Effects of a century of mining and industrial production on metal contamination of a model saline ecosystem, Great Salt Lake, Utah. Environmental Pollution (1987), 266, 115072–115072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115072

Media Attributions

- Figure1Aguilar

- Table1Aguilar

- Table2Aguilar

- Table3AAguilar

- Table3BAguilar

- Table3CAguilar

- Table4AAguilar

- Table4BAguilar