College of Humanities

57 Prized Possessions in Elderly Populations

Anna Jo Short

Faculty Mentor: James Tabery (Philosophy, University of Utah)

Introduction

Many people go through their lives collecting items. People have collections of rocks, unique buttons, or postcards. Some individuals form sentimental attachments to their belongings, and others prefer a minimalistic lifestyle that allows them to discard “clutter” at any chance. Some people hoard their belongings; holding onto meaningless items that many others deem as trash. I have observed these things in people of all ages, but since working as a receptionist for the past year at a local retirement home, I have also observed these behaviors in the elderly. I often find myself walking into a resident’s apartment to see their walls decorated with images, tables littered with books, and shelves stacked with trinkets. Amidst all of these belongings, I find myself wondering which item is the one they treasure the most. Then, I think of the saying, “You can’t take a U-Haul to Heaven.” If this is the case, and I’m fairly certain it is, I think of why they still own so many things; maybe it provides them with a sense of comfort while they wait out the inevitable?

The first question I thought of is something other researchers have already pondered, and several studies have been conducted to determine the most commonly valued possession among the elderly. Many of these studies have reached the same conclusion; they agree that photographs are the most commonly cherished possessions of seniors (Tobin, 1996). Additional research has discovered that there is a possible connection between the ownership of prized possessions and an elderly person’s happiness (Sherman & Newman, 1978). This is especially true when an older person moves to a new environment, such as a retirement home. Maintaining possession of their cherished item has been shown to help them ease into their new surroundings while nourishing their sense of self (Tobin, 1996).

Unsurprisingly, many of the photos in the possession of elderly people feature images of the past and often include snapshots of people who have since passed away. The constant reminder of one’s family and their past can provide a sense of belonging to the owner of the photo, but it can also help to ease death anxiety (Tobin, 1996). I believe that photographs featuring deceased family members present a constant reminder of mortality. In turn, this may serve as a way for individuals, especially the elderly, to come to terms with their death.

The senior living facility where I work houses about 265 residents in a ten-story building, and it incorporates apartments for residents in independent living, assisted living, and memory care. I am most familiar with the residents in independent living, as their health is often better than that of those in assisted living, which allows them to be more active. Because of our very active community, I chat with residents as they come up to my desk, or as they come and go from the building. As I said before, I also get to go inside the apartments to help them with small stuff, usually a television they can’t get to work.

Because of my interactions with the same group of residents and my ability to peek into their homes, I figured that researching this topic for my project would be plausible and fun to conduct. Researching the topic of possessions and their impact on residents is practical at a retirement home that houses dozens of potential interviewees. Previous studies have concluded that photos are seniors’ most cherished possession, and the ownership of such improves their quality of life. I found this to be true in my research, but I also found that these cherished possessions have an impact on the anxiety an elderly person has regarding death.

Interviews

Resident #1, George

I began my interviews with a resident with whom I share the closest connection. I will call him George. George usually finds himself sitting next to me in an empty chair behind the receptionist’s desk because he likes talking to me so much. I would say he likes to have conversations with me, but, I listen to him more than I speak. He repeatedly retells the same dozen stories, and I believe I have all of his stories memorized. Yet, I don’t mind listening to the renditions because he is an older gentleman with a great heart. I can see his genuine appreciation for having a friend, and I am more than happy to be that person for him.

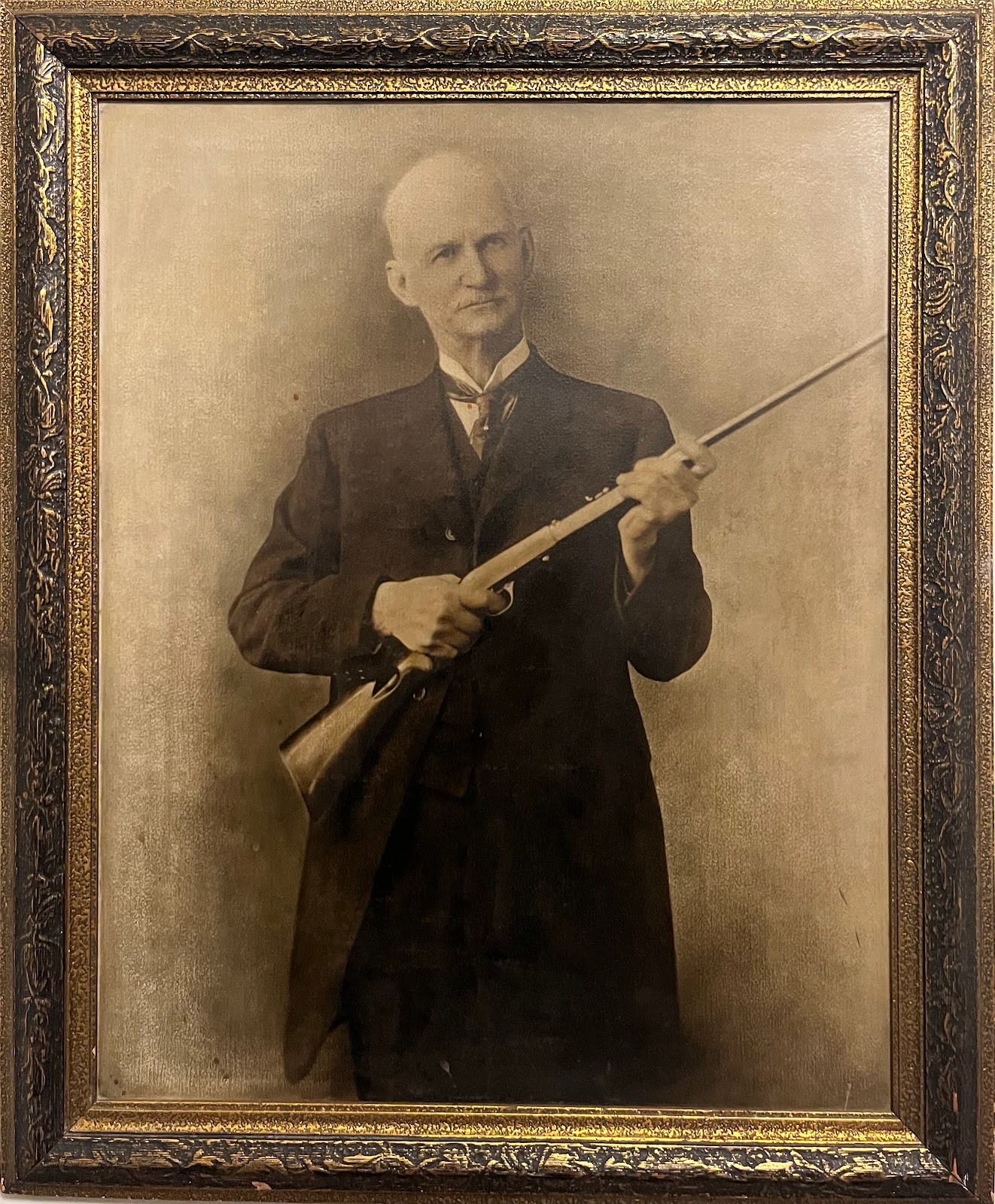

George’s history is particularly interesting. He is a Salt Lake native. He was born and raised in this city and graduated from East High School. Among the stories he tells me of his past are tales of traveling Europe with some notable Catholic priests, golfing with celebrities, his father’s high-profile involvement in the Democratic party, and stories of all the homes his family used to own. However, the most remarkable of these stories is that of his great-great-grandfather, John Moses Browning. That name should sound familiar, and what should sound even more familiar is this man’s most famous invention: the Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR).

John M. Browning was born in 1855, in Ogden, Utah. At thirteen years old, Browning crafted his first gun while working in his father’s shop (Rattenbury, 2024). Throughout his life, Browning patented over 120 individual firearm mechanisms and sold them to name companies such as Winchester, Colt, and Remington (Rattenbury, 2024). George often tells me that he wishes his great- great-grandfather was a better businessman. He tells me that Browning was too young and uneducated to have a fair hand in the profitable inventions he made. George also continually quotes Browning, who supposedly always said, “If it’s good enough for Uncle Sam, it’s good enough for me!” This was a statement he made regarding the BAR, which the U.S. Army used, and its mechanisms are still applied to modern guns today (Rattenbury, 2024).

George has several items in his possession; he has an older doll collection that belonged to his late mother, he collects rocks and Native American artifacts, and he has an impressive gathering of golf paraphernalia to show for his decades of dedication to the sport. However, the one thing he does not have anymore is Browning’s original M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle. Before moving to the retirement home where he currently resides, he lived in a different location. Upon moving into that location, they made George get rid of his guns. I guess they didn’t think it was wise for a then 85-year- old to have a rifle collection while living in an elderly community.

I wanted to snap an image of his most prized possession, but since the gun was no longer under his ownership, doing so was impossible. However, a quick Google search of the gun yields thousands of photos of the machinery. But, George insisted that I not include one of those photos in my project. Instead, he had me take a photo of a framed image on his wall that pictured his great-great-grandfather holding the BAR. It hurts my heart to think that such a valuable item that undoubtedly had a worldwide impact, whether for good or for bad, is in the hands of someone whom George may not even know.

Resident #2, Dolly

The next resident I interviewed is someone I will call Dolly. Dolly is currently 92, and she is a strong, faithful member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. Like George, Dolly was born in Salt Lake in 1932. She graduated from South High School (which is now a part of SLCC’s campus) at the age of seventeen in the year 1949. But, according to her, she was too young to get a job. So, she attended a business college run by the LDS church. About a year into her studies at the business college, Dolly had established a relationship with a man named Wesley. Dolly’s mother saw that their relationship was getting more serious, so she suggested that Dolly find employment now that she was old enough to hold a job. Doing so would allow Dolly to have some funds if she were to marry Wesley, whom Dolly affectionately calls Wes.

The church had connections with a local insurance company, so Dolly became employed as a receptionist at the agency. In February of 1952, Dolly married the love of her life, Wesley, at the age of eighteen in the Salt Lake City Temple. As I interviewed her, she lovingly recalled her relationship with her late husband, to whom she was married for 61 years. Their loving marriage physically ended in 2012 when he passed away.

Dolly had met him at church. One night she attended a church dance, and she danced with Wes. He scuffed up her new suede shoes at the dance, and she felt annoyed that her shoes were already marked up. But, to her dismay, the situation worsened when Wes started dancing with another woman. She hadn’t attended the dance as Wes’s date, but she felt fond of him and didn’t like to see him entertain the other girls. So, she left the dance early and walked home. But, to her surprise, Wes hadn’t forgotten about her. Roughly half an hour after she arrived home, Dolly’s father called for her. Wes was at the door, and he was distraught that she had left the dance early. They began to date after that night, and the rest was history.

Shortly after their marriage, Wes was called to serve in the military, and he was stationed in Wisconsin. Upon going to Wisconsin, he insisted that Dolly, his young bride who was now pregnant, accompany him. She followed him to Wisconsin, but when her due date neared, she traveled back to Utah to give birth to her first child while surrounded by support from her family. I asked her how she felt about her husband not being in the delivery room. Her answer surprised me; she said that she was alone in the delivery room, and it didn’t even occur to her that her husband should be present. She told me that his absence didn’t matter, as back then they administered so many strong drugs to laboring women that she doesn’t even remember the births of her first three children.

Dolly ended up having “seven + one children.” She likes to say it this way because her youngest son, Nathaniel, was born ten years after their seventh child, so she always felt that he had grown up as a single child. Dolly and Wes raised their children in the LDS church, and Dolly served as the town’s crossing guard for a local elementary school. Wes often called Dolly a “quick change artist” because she was always in her Sunday best, in her crossing guard uniform, or wearing an apron as she bustled around the house tending to the children. His statement is accurate, as Darlene wore many hats. However, the role that Darlene valued the most was being a mother. Her most valuable possession isn’t an item that you sit on the shelf or a dazzling piece of jewelry that you keep in a chest. Instead, it is her family. Her mother and father, her brother and sister, her late husband and their eight children, their thirty-five grandchildren, eighty great-grandchildren, and one great-great-grandchild are the most valuable things in her life.

Although it is impossible to gather all of these people together for one big family picture, Dolly was able to refer to two portraits that hung on the wall of her apartment. One of the framed images showed her children and their spouses, and the other showed her and Wes, their children and spouses, and some extended family members. These images served as a helpful point of reference when she explained her family’s dynamic, and they provided me with a visual of what her most prized “possessions” were.

Dolly told me that she feels at peace knowing that she will see her deceased relatives when she dies and that her living family will join her in the future. Her belief in the teachings of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints provides her with this knowledge, and the rest is out of her control. These are the images she showed me:

Prized Possessions & Happiness

Although George and Dolly didn’t technically identify photos as being their favorite item, they both referred to images that contained a visual representation of their actual prized possession. Interestingly enough, the identification of images as a person’s most prized possession is more common among the elderly rather than the younger generations. After conducting research among three generations, a study concluded that the middle and youngest generations valued furniture and stereos the most, respectively (Csikszentmihalyi & Rochberg-Halton, 1981). This is likely because as people age they find themselves downsizing and decluttering their spaces, which leaves less room for bulky items. On the other hand, younger generations usually have more space in their growing homes for larger items.

Both Dolly and George reside in a retirement home, which undoubtedly restricts how much they own. For example, George doesn’t own the BAR anymore, and Dolly doesn’t house her entire family in her one-bedroom apartment. Dolly told me that she tries to get rid of her material belongings as often as possible. A change in living arrangements has forced George to do the same, although he resists it. He does, however, proudly display the picture of his great-great-grandfather. Similarly, Dolly clings to the images of her family because the photographs portray something that is far more valuable than any material item.

This change in space is so common among elderly people, and a study conducted among residents in a nursing home found that those who managed to maintain ownership of their prized possessions were happier (Wapner et al., 1990). Those who were able to display their prized possession had also adjusted to their new living spaces better, leading to higher levels of satisfaction in their new situation (Wapner et al., 1990). Elderly residents enjoy placing their treasures around their new room to express themselves and help them feel at home in an unfamiliar place.

One of the most important aspects of material possessions is their stable appearance. Material possessions are very important in the fact that they remain unchanged over time. The concrete items unphased by the passage of decades hold a sense of immortality within them and serve as an everlasting reminder of someone’s past identity (Tobin, 1996). Maintaining possession of the objects seniors adore the most aids in providing stability in a changing environment (Tobin, 1996). These symbolic items, whatever they may be, assist in “the continuity of self.” This is particularly essential during a period of life that may erode all sense of self and independence as the body ages and daily tasks become harder to perform (Tobin, 1996). Once again, these items are even more vital to happiness and adaptation to change when an elderly person transitions between living arrangements, especially to a retirement home or a nursing home.

The unchanging nature of a photograph freezes a moment in time and preserves it forever. “The photograph not only represents what was once embodied in reality; eventually, it substitutes for that lost, irretrievable reality” (Gibson, 2008). This provides further evidence that when a senior settles into a new home, it’s not just the familiar decor that provides them with comfort, but their most cherished possession; most commonly identified as a photo. The photo likely features an image of the past, including family members and a happy memory in one frame.

Although my study pool is small, the two people I interviewed in many ways reflect the findings of previous studies and the connection between happiness and cherished materials. Firstly, George mentioned that the item he places the most value in is no longer in his possession. Contrary to this, Dolly’s prized possessions, although not objects, are still alive and visit her frequently. This means that George has no interaction with his prized possession, and he cannot physically show it to others. Dolly, on the other hand, has living family members whom she can introduce to others and invite to her home. These factors may play a role in their different levels of happiness.

For example, I previously mentioned that George repeatedly tells me versions of the same tales over and over, but what I failed to include was the absolute yearning he expresses to be young again, and the sadness and discontent he holds for his current living situation. He tells me of his travels and rich life experiences, many of which some people would never even begin to dream of having the chance to experience. But, instead of fondly reminiscing on these memories, he always ends the stories with sorrow and expresses his jealousy that I am young and can “go out on the town whenever I want.” He thinks he misses out on everything good in life. He says the retirement home isn’t his “home,” and that he wants nothing more than to just leave.

Dolly, conversely, seems completely content with her living situation and with the fact that she resides in a senior living facility. When she reflects on her past, she expresses gratitude for the hardships she endured and cherishes the fact that she created such a beautiful family. I’ve never heard her express that she wishes to be responsible for a family of ten again, but she tells me “It was so fun to have all those kids.” I imagine she’s forever grateful that she put herself through motherhood with eight children, but her hard work is done, and now she can reap the blessings by witnessing her family multiply exponentially. She knows what it is like to work towards something and be rewarded for it. She spent her entire life building something, and now her legacy lives on.

As other academic studies conducted on the correlation between happiness and ownership of cherished possessions suggest, this difference in joy between Geroge and Dolly may be due to what items they have left to memorialize who they were. Specifically, their access to the item they value the most. Both have images that contain a photo of their most valued item, but Dolly’s image represents something she can still obtain; while George is unable to access the object in his photo.

Prized Possessions & Death Anxiety

Aside from increasing the happiness in a senior’s life, possessions can also help ease the aging process and eventual acceptance of death around them, as well as their future death. This is likely the case because many photographs kept by the elderly act as a memorial for those who have passed away (Holst-Warhaft, 2005). Both photos that represent Dolly and George’s prized possessions show individuals who have died. In Dolly’s family photo, her husband has since passed away, along with other relatives posing in the image. Browning is no longer alive, and he is the sole person in the image that George has hanging on his wall.

This continual reminder of the temporary status of life calls to attention the mortality of human life. Often referred to as death anxiety, this feeling can be explained as the fear of the erasure of one’s existence (Greenberg et al., 1994). Death anxiety can be felt at any point in a person’s life, but it is likely to peak when a person knows they are nearing death, such as someone who is approaching the end of their natural life span (Chuin & Choo, n.d.). This period when someone is anticipating death, a state in which the self no longer exists, can be excruciating for people who have not accepted the idea of their death (Tomer, 1992). However, other studies have shown that the elderly population as a whole may not have the highest levels of death anxiety, and it can vary between individuals (Fortner & Neimeyer, 1999). Death elicits many feelings as a person thinks of their fate and the life they have lived to that point.

Prized possessions, which have an established link to an elderly’s happiness, may impact death anxiety among seniors differently. For instance, Dolly told me that she hopes to not die at Thanksgiving because that’s when her mother and grandmother died. She said she would hate to die during Christmas as that would be inconvenient for her family. Instead, she expressed that she wouldn’t mind dying by the New Year. Every time I hear a resident discuss their death in such a nonchalant tone, I am always shocked that they can speak about something so serious in such a casual way. I am continually reminded that some people at this stage in life do not fear death, but yearn for it. While I don’t believe Dolly necessarily yearns for it, I think she has fully accepted the prospect that she will pass away shortly, and aside from scheduling conflicts that may arise as a result of her death, she doesn’t have much anxiety surrounding this event. This may be due to her sense of fulfillment in life, content with her current situation, and even access to her “prized possessions” that feature loved ones who have passed on.

George, however, does not openly discuss his death. I feel that he has a much higher level of anxiety regarding his death than Dolly. He does recall all the events that have occurred in his life, which is common when someone nears death. But, reflecting on one’s life may evoke regret (Lehto & Stein, 2009). I think George regrets getting old, even though that was never under his control. His discontent with his life makes me suspect that he feels there is still much more to be accomplished.

Because of this, he wishes to not die so he can have the chance to achieve the rest of his goals. I believe he hopes that the retirement home is a temporary situation while other things are worked out, and at some point, he can reinstate his life of freedom and travel. I know he would dislike the senior living facility where he currently resides to be his last home in life. I suppose he has anxiety thinking that until his death, this might be his last living arrangement. George’s lack of acknowledging the inevitable and living in the past produces death anxiety. This makes me worried that he won’t know to seize the present time until it’s too late.

My observations of George’s behavior, especially about his death, make me wonder if his lack of acceptance could be due in part to his prized possession. Although I’m sure there are a plethora of other factors that play into his well-being and his denial of death, his lack of connection to his prized possession may partially contribute to how he feels about his aging process. His discontent may be connected to the fact that the image showcasing his prized possession presents an item that he no longer owns. Rather than sparking feelings of pride due to his family history, this image might cause him to feel longing for something that he no longer has. Dolly, on the other hand, still has access to her favorite things that are displayed in the image. Although the pictures freeze a look of youth and show faces untouched by time, she was still very present during the time the image was taken. So, the memories elicited by the family portrait that hangs on her wall are of admiration instead of yearning, because she feels a sense of identity and self in the image, rather than longing for a period that can never be revisited.

Conclusion

It’s human nature for people to collect material items. Especially in Western cultures, where brands and consumerism are driven by capitalism. Everyone competes to own the most of the best items. After decades of life on earth, elderly people have collected more than younger generations. But, which of these items are the most valuable in a sentimental sense, regardless of their monetary worth? And, how do the elderly decide which of their belongings is the one they cherish the most? Well, after analyzing previous studies conducted on this topic and collecting data from residents whom I personally interviewed, I have concluded that photos are the most valued objects among residents.

However, I further discovered that it isn’t about the photo itself, but the subject featured in the photos. For Dolly, it was her beloved family members. As for George, it was one of his ancestors showing his famous invention.

My results also matched those of previous studies that claimed the possession of a cherished item may increase life satisfaction among elders, as they can find a sense of identity and self in an object that doesn’t change over time. This aids in one’s transition between living arrangements as well. Displaying photos that show a loved one who has passed away can be a continual reminder of mortality, which can invoke self-reflection and one’s feelings about their death. This can decrease death anxiety if an elder grows to accept their fate, but as I observed in one of my interviewees, this is not always the case. Neither Dolly nor George had plans for the photos, nor the objects they depicted, after they passed away. I gathered that the things featured in the photos were much more important to them than any plan they could create for inheritance.

Bibliography

Chuin, C. L., & Choo, Y. C. (n.d.) Age, Gender, and Religiosity as Related to Death Anxiety. Sunway Academic Journal. https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Rochberg-Halton, E. (1981). The Meaning of Things: Domestic Symbols and the Self. Contemporary Sociology A Journal of Reviews. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/224927533_The_Meaning_of_Things_Domestic_Symbols_and_the_Self.

Fortner, B. V., & Neimeyer, R. A. (1999). Death Anxiety in Older Adults: A Quantitative Review. Taylor & Francis Online. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/074811899200920?needAccess=true

Gibson, M. (2008). Objects of the Dead: Mourning and Memory in Everyday Life. Melbourne University Publishing. https://books.google.com/bookshl=en&lr=&id=2kZUgcJvcswC&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=elderly+and+possession+of+photos+of+loved+ones&ots=i83eL3k6M&sig=YDKXPfFEAhBuB9o7FlZsMGkcrq4#v=onepage&q&f=false

Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., Solomon, S., Simon, L., & Breus, M. (1994). Role of Consciousness and Accessibility of Death-Related Thoughts in Mortality Salience Effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/1995-05334001.pdfauth_token=ded9f79b5cde4e15a5d8b733dbbe0edcd0cb0d8f.

Holst-Warhaft, G. (2005) Remembering the Dead: Laments and Photographs. Duke University Press. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/185345

Lehto, R. H., & Stein, K. F. (2009). Death Anxiety: An Analysis of an Evolving Concept. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice: An International Journal. https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/66464/Death%20Anxiety%20An%20Analysis%20of%20an%20Evolving%20Concept.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Rattenbury, R. C. (2024). John Moses Browning. Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Moses-Browning

Sherman, E., & Newman, E. S. (1978). The Meaning of Cherished Personal Possessions for the Elderly. National Library of Medicine. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/892918/.

Tobin, S. S. (1996). Cherished Possessions: The Meaning of Things. American Society on Aging. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44877948?seq=3.

Tomer, A. (1992). Death Anxiety in Adult Life- Theoretical Perspectives. Pennsylvania State University. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/07481189208252594needAccess=true

Wapner, S., Demick, J., & Redondo, J. P. (1990). Cherished Possessions and Adaptation of Older People to Nursing Homes. National Library of Medicine. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2272702/.