School for Cultural and Social Transformation

6 US and British Imperialist Destabilization in Guatemala and Jamaica Through the Banana Trade

Gabriela Merida

Faculty Mentor: Andrea Baldwin (Ethnic Studies and Gender Studies, University of Utah)

ABSTRACT

The banana is a widely appreciated fruit, enjoyed daily by millions worldwide. However, many consumers remain unaware of the bloody history associated with its trade. The historical narrative surrounding the banana industry has often been overlooked or intentionally excluded from educational curricula because of its stark illustration of the violence inherent in Western imperialism. The people and regions of Latin America and the Caribbean, however, have not forgotten; they continue to confront the ramifications of the banana trade and the lasting legacies of U.S. and British imperialism, which have indelibly shaped their economic and political realities.

This project examines the historical cases of Guatemala and Jamaica to investigate how Western imperialist powers, specifically the United States and the United Kingdom, have collaborated to destabilize these nations, in part, through control over the banana trade. While much research has addressed the trade disputes between the U.K. and the U.S., limited analysis has examined how both nations leveraged a monopoly over the banana industry, sharing strategies to destabilize and control these regions to sustain their imperialist ambitions.

“As long as capitalism and imperialism go unchecked there will always be exploitation, and an ever- widening gap between the haves and the have-nots, and all the evils of imperialism and

neocolonialism which breed and sustain wars.”

Pan-Africanist Revolutionary and first President of Ghana, Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, Challenge of the

Congo, p. x

INTRODUCTION

I come to this work as the daughter of a Guatemalan immigrant whose childhood was shaped by poverty, hunger, and displacement. My father grew up in the shadow of the 1954 U.S.-backed coup d’état against President Arbenz, witnessing firsthand the stark inequalities and violence of Guatemala’s civil war. As a child, he was often left to care for his siblings for months on end while his parents sought work. The trauma of those years remains with him, though much of what happened is locked away in memory he can no longer access.

In an effort to understand the legacy of that trauma, I began studying the history of the coup in Guatemala and its enduring consequences. I quickly encountered the devastating truth: the United States orchestrated the overthrow of democratically elected President Jacobo Árbenz to protect its imperialist interests and those of the United Fruit Company, a major U.S. corporation. What followed was a dictatorship and brutal U.S.-backed military campaign that claimed the lives of more than 200,000 Guatemalans—83% of whom were Indigenous Maya (UN Commission for Historical Clarification 17). Two hundred thousand lives. My people. Tinam.

My exploration into Guatemalan history revealed the far-reaching impact of U.S. imperialism. I came to understand that the hardships my family and I experienced in the United States were directly connected to the violence and economic turmoil wrought by U.S. intervention in Guatemala. The same imperialist forces that pushed my parents to migrate continued to oppress the lives of Guatemalans at home.

This pattern is not unique to Guatemala. Across the Global South, Western powers have intervened to protect their interests, often at catastrophic cost. The assassination of Patrice Lumumba in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the joint U.S.-British overthrow of Prime Minister Mohammed Mosaddegh in Iran, and the U.S.-backed coup against President Salvador Allende in Chile are just a few examples. These nations were stripped of their resources and sovereignty in the service of Western capital.

With this understanding, I became interested in how imperialist powers—particularly the U.S. and Europe—collaborated and shared tactics in destabilizing the Global South. I wanted to trace these interconnections, to uncover a shared genealogy of resistance among colonized peoples. I chose the banana trade as my point of entry because it offers a clear, tangible example of how foreign policy and economic domination intersect, shaping the political and economic systems of Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) to this day.

My research builds on the work of influential scholars such as Eduardo Galeano, Eric Williams, Stephen Schlesinger, and Peter Clegg, whose writings have deeply informed the study of imperialism, colonization, and the exploitation of Indigenous and African-descended peoples in LAC (Galeano 1971; Williams 1970; Schlesinger 1982; Clegg 2002). This paper contributes to this body of scholarship through a comparative study of the banana trade in Guatemala and Jamaica—two countries whose shared history is often overlooked. By highlighting the struggles of both Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities, I seek to emphasize the importance of an internationalist lens in both historical analysis and contemporary struggle.

Thus, the central question my research answers is: How have U.S. and British imperialist forces collaborated to destabilize Guatemala and Jamaica and maintain economic domination in Latin America and the Caribbean through the banana trade?

This paper begins with a review of the foundational literature that informs my analysis. The writings of Marxist theorists such as Vladimir Lenin and Nikolai Bukharin have shaped my understanding of imperialism as a global system (Lenin 1917; Bukharin 1917). Historians such as John Soluri and Charles Kepner provide detailed accounts of the banana trade that have informed the structure of this work (Soluri 2024; Kepner 1935).

I will then turn to historiography as my main methodology to examine the banana trade in Guatemala and Jamaica, synthesizing secondary sources alongside trade records, CIA documents, US and UK National Archives, and historical imagery. My analysis is grounded in a Marxist framework, applying Lenin’s theory of imperialism to interpret both historical and contemporary developments.

The historiographical analysis focuses on five key periods in Guatemalan and Jamaican history: (1) colonization (15th–18th centuries), (2) independence movements (18th–19th centuries), (3) the emergence of the banana trade (late 19th–early 20th centuries), (4) the post–World War II era (1940s–1960s), and (5) the contemporary period (1980s–present). Drawing from these sources, records, and archival materials, I ultimately argue that the United States and the United Kingdom have employed similar—and at times coordinated—economic, military, and diplomatic strategies to destabilize these nations through the banana trade.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Colonialism in Latin America and the Caribbean

The history of colonialism in Latin America and the Caribbean spans over five centuries, beginning with Christopher Columbus’s arrival. From the outset, Western imperialist nations coordinated to conquer the so-called New World, exploiting its land, resources, and labor to accumulate capital. Peruvian sociologist Aníbal Quijano argued that the colonization of the Americas introduced a “new global model of power” (Quijano 539). Capitalism became the first “modern world- system,” as theorized by Immanuel Wallerstein or a “world economy,” as defined by Marxist Nikolai Bukharin (Wallerstein 1974; Bukharin 1929). The enslavement and genocide of Indigenous peoples and Africans formed the “founding stone” of this new global economic order (Du Bois 15). As Karl Marx (1867) wrote, “The discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation, enslavement, and entombment in mines of the aboriginal population… the commercial hunting of black-skins, signalized the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production.”

As capitalism developed in Europe, so too did the demand for raw materials and labor power (Lenin 79). The colonization of the Americas and the kidnapping and enslavement of Africans proved to be a “profitable” investment, as the wealth plundered through their forced labor flowed back to Western Europe, fueling capital accumulation there (Lenin 60). Capitalism, through colonization, structured the division of labor, assigning unpaid labor to Indigenous people and enslaved Africans while constructing race and racial identity to justify their exploitation (Quijano 534-539). In this way, the development of capitalism in Latin America and the Caribbean would have a colonial character (Quijano 539).

Banana Trade in Latin America and the Caribbean

The banana trade in Latin America and the Caribbean illustrates the violence and “wretched conditions” fundamental to the capitalist mode of production (Lenin 60). The literature on the banana trade in this region provides an entry point into understanding the broader implications of Western imperialism and how the development of the West has relied upon the underdevelopment of the Global South (Galeano 41; Nkrumah, 7; Rodney 1972). The economic structures of Latin America and the Caribbean have been shaped by a history of European colonialism, which has imposed a dependency on the export of raw materials and agricultural products to fuel Western development (Josling & Taylor 98). The banana exemplifies a single-export commodity upon which many nations in the region have relied, structuring their economies around its production and trade. These nations have become known as ‘banana republics’ (Josling & Taylor 98).

Historians Stephen Schlesinger and John Soluri trace the origins of the Latin American and Caribbean banana trade to Jamaica in 1870, when Captain Lorenzo Dow Baker arrived and purchased bananas to trade for the first time (Schlesinger 65–66; Soluri 146). From there, Baker formed the Boston Fruit Company and left his home in the United States to reside permanently in Jamaica to supervise banana shipments (Schlesinger 66). Minor Keith, an American entrepreneur, was also developing a banana trade in Central America around the same time (Schlesinger 67). Boston Fruit and Keith struck a partnership, and the two companies merged to create the United Fruit Company (Clegg 24; Schlesinger 67; Kepner, 34).

The literature on the United Fruit Company is extensive, as it is one of the most explicit examples of an undisputed capitalist monopoly that not only had the complete support of the United States government but also had the political and economic strength to shape foreign policy and expropriate the labor and means of production of nations in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) (Kepner 341). The United Fruit Company, as the “unquestioned lord of…the banana industry,” was capable of overthrowing governments and committing some of the worst human rights atrocities recorded in LAC (Kepner 341; Josling & Taylor 99).

Guatemala and Jamaica

The literature on the banana trade in Latin America and the Caribbean explores both its broader implications and nation-specific case studies. Kepner provides a comprehensive analysis of the trade across the region, while Dr. Peter Clegg focuses on its development in Jamaica (Kepner 1937; Clegg 2002). Both perspectives are essential to understanding the full scope of the banana trade in LAC. However, an analysis comparing the banana trade in Guatemala and Jamaica has yet to be published. This absence is striking, given their shared histories of colonial exploitation and ongoing trade disputes. The lack of such a comparative study reflects a broader pattern in how the West constructs history to obscure the interconnectedness of struggles faced by colonized nations. This paper aims to fill the gap by conducting a comparative study of Guatemala and Jamaica, examining their shared genealogy in the banana trade and how the United States and the United Kingdom have employed similar and shared tactics in destabilizing these nations.

The early banana trade in Jamaica was developed entirely by Black Jamaican smallholders who turned to banana cultivation to escape the oppressive conditions of the sugar plantation (Soluri 144). The success of Afro-Jamaican smallholders drew the attention of American corporations like United Fruit, which soon gained a monopoly over the market (Soluri 144). In Guatemala, dictator Manuel Cabrera granted United Fruit the country’s principal rail line, which would be the beginning of a long history of United Fruit’s monopoly over the banana trade in the country (Schlesinger 67-70). The literature shows that United Fruit would work to eliminate competition and gain as much political and economic control in both countries. This would ultimately culminate in the overthrow of President Jacobo Arbenz and the genocide of the indigenous Maya, as well as the ‘banana wars’ and neocolonial policies that would threaten the livelihood of smallholders and the survival of the Jamaican banana trade (Schlesinger 257; Courtman 252).

Introduction of Method

I will use historiography to examine the history of the banana trade in Guatemala and Jamaica by synthesizing the writings of historians and historical records like trade reports, CIA documents, and the US and UK National archives. Historiography is the writing of history by examining critical sources, highlighting specific details, and synthesizing them to create a compelling narrative (Encyclopedia Britannica 2025). The method of historiography has historically been understood as compiling a catalog of contributions made by historians that advanced knowledge of a particular topic (Becker 21-22). However, late historian Carl Becker contends that a historiographer must also seek to understand the underlying beliefs and assumptions of the time and “cultivate a capacity for imaginative understanding” (Becker 22). Trevor Burnard’s Empire Matters? The Historiography of Imperialism in Early America, 1492–1830 masterfully demonstrates how historiographers can integrate the writings of historians and historical documents to provide a more comprehensive analysis of the history of colonized nations (Burnard 2007).

Connection with Research Question

The method of historiography will effectively test my research question as I analyze the writings of historians like Stephen Schlesinger and Peter Clegg and situate their writings within my analysis of historical documents. Historiography is an effective method for addressing my research question: How have Western imperialist forces collaborated to destabilize nations and maintain their colonies in Latin America and the Caribbean through the banana trade? By examining both secondary sources, such as the works of historians like Stephen Schlesinger and Peter Clegg, and primary historical documents like CIA telegrams, letters, and trade reports, I will be able to analyze how colonial and imperialist powers exerted control over the banana trade in Guatemala and Jamaica. This approach will allow me to contextualize historical narratives within broader patterns of Western imperialism.

Methods of Data Collection

I will collect my data by reviewing historical writings and documents on the banana trade in Guatemala and Jamaica. I will analyze the works of prominent scholars in the field as they trace the development of the banana trade in Guatemala and Jamaica from colonization and slavery to semi- feudalism to the rise of capitalism and neocolonialism. I will review historical and trade documents from repositories like the US and British National Archives and the UN Archives as well as from the bibliographies of my secondary sources. The data I compile from my document review will supplement the writings I analyze and provide insight into how Western imperialism has shaped the political and economic systems of Guatemala and Jamaica through the banana trade and more broadly.

Results Analysis

I will evaluate my results employing a Marxist framework and using V. I. Lenin’s theory of imperialism. Using this framework, I will trace how the United Kingdom and the United States have worked together to colonize the Americas and develop a global system of capitalism that relies on the underdevelopment of the Global South. The tradition of Marxist historiographies includes a vast body of work that examines the materialist conditions of imperialist exploitation and the interconnectedness of economic and political forces in shaping colonial legacies (Lenin 1917).

Rationale for Methodologies

Historiography enables a critical synthesis of primary and secondary sources, allowing me to trace imperialist intervention across different historical moments and scholarly debates. Through historiographical analysis, I can uncover how narratives around U.S. and British involvement have been constructed, contested, and reinterpreted over time. At the same time, applying a Marxist framework, particularly Lenin’s theory of imperialism, situates these historical processes within the broader dynamics of capitalist accumulation. A Marxist analysis exposes how the exploitation of nations like Guatemala and Jamaica was not incidental but central to the expansion of a global capitalist system reliant on the underdevelopment of the Global South.

Justification for Subject Selection & Sampling Procedure

I have selected Guatemala and Jamaica as my case studies because both nations have historically played significant roles in the global banana trade and have been directly impacted by Western imperialism. These two countries illustrate how the United States and the United Kingdom have shaped the economic and political world-system to accumulate mass profits off the oppression and subjugation of colonized people in the Global South. My sampling procedure involves selecting primary sources such as trade reports, historical documents, and declassified government documents from archives that reflect these imperialist relationships.

Potential Limitations

One potential limitation of my study is the availability and accessibility of archival materials. Some documents may be classified, incomplete, or difficult to obtain. I will also be relying on existing scholarship that may be biased or rely on outdated information. Another limitation is the scope of my research—focusing on Guatemala and Jamaica provides an in-depth look at two nations but does not capture the full extent of Western imperialist influence on the banana trade in other regions. Despite these limitations, my study will contribute to a deeper understanding of Western imperialism in Latin America and the Caribbean and trace the legacy of colonial and capitalist exploitation perpetrated by the United States and the United Kingdom in these regions. This analysis will be grounded in reputable, peer-reviewed scholarly sources, ensuring a strong academic foundation, and will be further enhanced by primary materials uncovered through archival research.

RESULTS, ANALYSIS, DISCUSSION

In this section, I will conduct a historiographical analysis and examine five key periods in the history of Guatemala and Jamaica. I will begin with an overview of each period to illustrate the shared genealogy between these two nations and examine how Western imperialism, particularly through the banana trade, has shaped each country’s political and economic conditions. Then, I will analyze historical documents from each period to demonstrate how the United Kingdom and the United States employed similar and shared military, political, and economic tactics to destabilize both Guatemala and Jamaica through their control of the banana industry.

Colonization & the Slave Trade

Christopher Columbus arrived in Jamaica in 1494, and soon after, the Spanish colonized the land and enslaved the native Arawak people (Nicholas 2023). A majority of the native Arawak would be killed or die from diseases that the Spanish had brought with them; some would escape to the mountains, where they would reside with runaway enslaved Africans, forming the Maroons (Nicholas 2023). Spanish colonist Juan de Esquivel brought the first enslaved Africans to the island in 1513 (Ferguson et al. 2025). The English grew increasingly wary of the Spanish ‘monopoly’ over the New World and began to challenge Spanish hegemony in the Caribbean (Williams 72). As a result, the English successfully captured and gained formal possession of Jamaica from the Spanish in 1655 (Williams 114).

As the sugar industry began to grow in the Caribbean, the British government was quick to invest in the kidnapping and enslavement of West Africans to work on the sugar plantations (Williams 104, 114, 138). Former Trinidad and Tobago Prime Minister and historian Eric Williams wrote in his seminal book, From Columbus to Castro, that the “triangular trade” (slavery, slave trade, and the sugar plantations) was extremely profitable to the British Empire and accounted for nearly 10% of total British exports (142). By the end of the century, the trade amounted to two million pounds in profits for the British alone (143). In the words of English businessman Sir Dalby Thomas, “The pleasure, glory and grandeur of England has been advanced more by sugar than by any other commodity” (Williams 144). This glory relied upon the mutilated and tortured flesh of enslaved Africans (Spillers 67).

In the 17th century, an estimated 1 million Africans were kidnapped and taken to Jamaica (Nicholas 2023). Their journey on the Middle Passage was marked by the most brutal violence and cruelty. On slave ships, enslaved Africans endured horrific, crowded conditions, physical and sexual torture, and disease (Wolfe 2020). These appalling conditions were met with resistance as the Africans on board organized armed revolts, hunger strikes, and committed suicide by jumping overboard (Wolfe 2020). Around 15-20 percent of enslaved Africans would not survive the trip across the Atlantic (Rodney 96).

In the Caribbean, the conditions on the plantations were backbreaking, and the death rates of enslaved Africans were high while the birth rate remained low (Mintz 2025; National Museums Liverpool 2025). Therefore, the sugar plantation economy relied upon the continued importation of enslaved Africans to maintain the population (Mintz 2025). The Guyanese revolutionary thinker and Marxist scholar Walter Rodney traces the underdevelopment of Africa to the European slave trade, which was devastating for the political and economic systems in African countries, as well as family and community structures (102).

While the Caribbean plantation economy reveals one facet of imperialist exploitation through the transatlantic slave trade, similar patterns of conquest, brutality, and resistance were unfolding on the Central American mainland. In 1524, Spanish conquistador Pedro de Alvarado, lieutenant of Hernán Cortés, invaded and terrorized the Guatemalan highlands, overtaking K’iche warriors and burning alive tribal leaders (Immerman 20). The Mayan empire, one of the most advanced civilizations of its time, would collapse within a year as smallpox ravaged the Maya population and Alvarado spread terror throughout the region (Immerman 20). His campaign against the Maya was so brutal that Cortés complained to Spanish King Charles V because his violence only sparked more resistance from the Maya people (Wainer 2024). In his letter, he wrote, “Although Pedro de Alvarado makes constant war against [the Maya]…he has been unable to subject them to Your Majesty’s service; rather each day they grow stronger through the people that come join them” (Cortés 215). Although the Maya continued to resist through guerrilla warfare tactics, Alvarado was able to exploit conflicts between tribes and gain enough indigenous allies to defeat the Maya (Cartwright 2022).

During the tyrannical regime of Alvarado, population levels in the Guatemalan highlands dropped by 90 percent, and it is estimated that over five million Indigenous peoples were killed in Guatemala alone through biological warfare, brutal enslavement, and bloody massacres (Oblesby et al. 2011). The twin violences of genocide and the enslavement of African and Indigenous peoples carved wounds into both flesh and land—ruptures through which the modern world-system of capitalism was born.

Independence and Emancipation

Although Guatemala achieved independence and Jamaica gained emancipation in the 19th century, these events did not bring true liberation to the majority of their populations. Both countries remained deeply embedded in a racialized division of labor established under colonial rule and slavery, and the emerging capitalist economies continued to rely on the unpaid or severely underpaid labor of Afro-descendants and Indigenous Guatemalans to sustain Western development and corporate interests (Quijano 54). Guatemala, with the help of Mexico, achieved independence from Spain in 1821 (Immerman 21). As Mexico attempted to incorporate Guatemala into its territory, Guatemala resisted and united with the rest of Central America to create a federation, thereby maintaining its sovereignty (Immerman 21). This federation was short-lived, but the idea of a united Central America would have a lasting influence on President Arbenz.

Historian Richard H. Immerman describes that before colonization, the Maya shared land governance and cultivated the land with the economic goal of “subsistence and participation in the community, not capital accumulation” (Immerman 25). After the conquest, Maya faced a continued threat from colonial rulers as they continued to steal and deprive Maya communities of their lands. Colonial authorities enacted laws to “legally deprive” Maya peoples of their communal properties by requiring titles to private property (Immerman 23). The expropriation of their lands forced the Maya to migrate from the highlands to agricultural regions, which guaranteed a cheap source of labor for colonial authorities (23).

United Fruit Company, “Scrapbook of United Fruit Company Photographs, 1917-1931” (1917). Select Florida Studies Manuscripts. 8. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/fl_manuscripts/8

Through the colono system, the Maya were forced into debt slavery. Immerman details how the latifundio-minifundio system exploited the Maya, forcing them to surrender 50–60% of their crops to landowners and accumulate debt to cover production costs and basic needs (28–29). To work off their debt, they were forced to labor on the landowners’ plantations during the summers for little to no pay.

Meanwhile, emancipation came later and under different terms; independence would not come until 1962 in Jamaica. The British Parliament signed the bill for the abolition of slavery in 1838, which would emancipate approximately 311,000 enslaved Africans in Jamaica and hundreds of thousands more across the British colonies (National Library of Jamaica 2025). However, Africans were not fully free until after a mandatory six-year apprenticeship, after which they could buy their freedom (NLJ 2025). Historian Eric Williams describes the semi-feudal system in post-abolition Jamaica, where emancipated Africans were given no option other than to work five-day weeks for as little as five cents an hour (Williams 328–330). Like the Maya in Guatemala, they remained tied to land systems that reinforced racial and economic exploitation even after formal independence or emancipation.

Start of the Banana Trade

Historian John Soluri traces the origins of banana production in Jamaica following emancipation from slavery, when Black Jamaicans turned to banana cultivation as a means of escaping the oppressive conditions of the sugar plantations (144-145). Before emancipation, enslaved Africans cultivated bananas to exchange in local markets for shade crops —such as cacao and coffee, which thrive under the canopy of larger plants— and their consumption (Soluri 145). Jamaican women played a vital role in marketing and selling these bananas (145). Soluri contends that bananas have been closely tied to conceptions of Blackness, and therefore, Afro-Jamaican smallholders, independent farmers, dominated production due to the hesitancy of white planters (145).

With the decline of the sugar industry, Afro-Jamaicans were able to purchase small plots of land to cultivate bananas. The impact of Afro-Jamaican smallholders on the local and export markets during this period cannot be overstated, as they produced the majority of the food in the country. In the words of historian Thomas Holt, “During an era in which racist ideology was becoming more virulent and practically unchallenged, official policy was grounded paradoxically on the entrepreneurship of Black Jamaicans” (Holt 317). However, colonial officials regarded their agricultural practices as “backward,” and their technical advice reflected the condescending, paternalistic attitude of the British government toward its colonies (Soluri 144).

United Fruit Company, “Scrapbook of United Fruit Company Photographs, 1917-1931” (1917). Select Florida Studies Manuscripts. 8. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/fl_manuscripts/8

North American traders began purchasing bananas from Jamaican smallholders in the late 1860s (Soluri 146). In the early 1870s, American businessmen George Busch and Lorenzo Dow Baker began to regularly ship bananas to the United States (Clegg 24). As the banana trade began to expand, Baker’s shipping company, the Boston Fruit Company, saw an opportunity to reap substantial profits by establishing its own banana plantations to meet growing demand (Schlesinger 66). However, they needed new sources of supply as the banana farms in the Caribbean were being depleted of their resources (66).

In Central America, Minor Keith built Costa Rica’s first railroad at a horrific human cost that took the lives of hundreds of workers (Immerman 69). Keith’s 112 miles of railroad dubbed him the “uncrowned king of Central America” (Schlesinger 67). Despite his reputation, he remained perpetually in debt and was forced to begin exporting bananas, eventually founding three banana companies to stay financially afloat (Immerman 69). Keith needed capital, and Boston Fruit needed more supplies, so they instituted a partnership and merged their companies to create the United Fruit Company (UFC) (Schlesinger 67).

Jamaican growers became increasingly concerned about the power and influence of American corporate interests, such as the United Fruit Company, over banana production (Clegg 26). In 1901, the Jamaica-UK banana trade was created to provide an alternative to the American market (Clegg 29). Historian Peter Clegg details how the British company Elders & Fyffes sought to challenge the United Fruit Company’s monopoly over the trade and fulfill its “colonial responsibility” to Jamaicans (Clegg 1, 29). As competition between Elders & Fyffes and UFC grew, Elders & Fyffes faced some difficulties, such as getting a steady supply of bananas “at prices acceptable to the UK market” (Clegg 31). They were forced to ask for assistance from the American corporation several times and eventually became a full subsidiary of the UFC (Clegg 34).

The resources that the UK government poured into building a sustainable UK-Jamaica banana trade were now being used to support an American company (32). The UK government’s reluctance to challenge American corporate power allowed the UFC “to expand and to stretch its tentacles over [Jamaica]” (Parker 6). In response to these pressures, Jamaican workers and small farmers began to mobilize. Labor strikes and rural protests emerged in the 1930s as workers pushed back against exploitative wages, corporate control, and the colonial state. These struggles were not only about economic survival but also about reclaiming autonomy in a system that had long prioritized foreign profits over the lives of Jamaicans (Hart 2002). It was ultimately Jamaican growers who came together to establish the Jamaica Banana Producers’ Association, aiming to challenge the United Fruit Company’s power and influence over the region (Clegg 39).

In Guatemala, the United Fruit Company not only gained a monopoly over banana production but also became the largest landowner, employer, and exporter in the country (Schlesinger 70). UFC had control over the railroads and over the trading ports and owned entire towns (Schlesinger 70). By the 1930s, the brutal Guatemalan dictator, Jorge Ubico, would sign a ninety-nine-year agreement with UFC to open a second plantation and grant them “total exemption from internal taxation, duty-free importation…and a guarantee of low wages” (Schlesinger 70).

The United Fruit Company paid Guatemalan workers no more than fifty cents a day—a wage that President Ubico deliberately endorsed to discourage demands for better pay from other workers (Schlesinger 70). Known locally as la frutera, the company was notorious for its exploitative labor practices and aggressive attacks on labor unions (Schlesinger 71). The UFC also manipulated racial divisions, pitting ladinos and Afro-descendants against each other to undermine labor organizing efforts (Gillick 1994). Racism was embedded in the company’s policies; workers of color were required to “give right of way to whites and remove their hats while talking to them” (Schlesinger 71). Guatemala could not attain genuine economic or political independence while the UFC—and broader American corporate interests—controlled nearly every aspect of workers’ lives, from housing and healthcare to their children’s education (Schlesinger 71).

Post-WWII

Near the end of World War II, the United States and the United Kingdom led the effort to establish a “new international financial system” (Igwe 111). The Bretton Woods system would enshrine U.S. hegemony, requiring all other nations to peg their currencies to the U.S. dollar (Patnaik & Patnaik 130). The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank were created under this system to pressure countries in the Global South to open their markets, often at the expense of their development (Igwe 111). A few years later, the Cold War gave rise to a wave of anti-communism that was weaponized against decolonized nations seeking economic and political independence from their former colonial powers. During this period, the United States and the United Kingdom would work together to systematically destabilize nations in Latin America and the Caribbean through covert military operations and economic means of control.

During World War II, the United Kingdom halted all banana imports due to the growing demand for ships to support the war effort (Clegg 58). This effectively ended the banana trade in Jamaica — “a once large and profitable export industry” (59). Willis Berry, a Jamaican civilian, recalled that one of the most damaging consequences of the war was its disruption of imports and exports (Berry 2005). He noted that “people would walk 4–5 miles to get goods” such as oil, petrol, and rice, while a ban on imports led to a surplus of local agricultural products like bananas (2005). After the war, Jamaican growers pressured the UK government to permit the import of bananas once again (Clegg 60).

However, the global trade landscape had shifted. The United States, now the dominant economic power, flooded markets with cheap “dollar bananas” from Central America, backed by the United Fruit Company. These U.S.-backed bananas were produced at a scale and price point that Britain and its former colonies struggled to compete with. The UK government, burdened by post-war debt and dollar shortages, saw continued trade with U.S. banana companies as financially unviable, since it would drain precious U.S. dollar reserves. Instead of protecting the interests of Jamaican growers, the UK was “determined to remove itself from the trade” altogether. It forced the Jamaica Banana Producers’ Association to return control of the industry to United Fruit via Elders and Fyffes (Clegg 67).

In 1962, Jamaica achieved independence from Britain, and its government transitioned from the colonial authorities to a small, Western-backed elite that did not reflect the masses of Afro- Jamaicans who were in poverty, unemployed, and forced to live in the slums (Chukwudinma 2022). This contradiction fueled the rise of the Black Power movement, which sought to challenge the neocolonial structures that persisted post-independence. A pivotal moment occurred in October 1968 when the Jamaican government barred Guyanese revolutionary Walter Rodney from re-entering the country after attending a Black Power conference in Canada. Rodney’s activism and engagement with the poor had made him a symbol of resistance against oppression (Chukwudinma 2022). His deportation sparked widespread protests, known as the Rodney Riots, where thousands of students, Rastafarians, farmers, and working-class youths took to the streets of Kingston, setting buses ablaze and looting American companies, all while chanting “Black Power” (Chukwudinma 2022). Rodney theorized Black Power as a direct challenge to what he called the “white imperialist system” (Rodney 41). These riots underscored the deep-seated frustrations of Afro-Jamaicans and highlighted their active resistance to ongoing Western imperialism, particularly as it was manifested through American corporations such as the United Fruit Company.

In Guatemala, Ubico’s thirteen-year dictatorship wrought terror on indigenous farmworkers, students, union leaders, and anyone who opposed his regime (Immerman 33-34). He used the accusations of conspiracy and treason to justify their imprisonment, torture, and execution (34). Ubico worked to systematically oppress the Maya by forcing them to join the military to “transform them from this ‘animal-like’ condition into ‘civilized’ individuals” (35). He also stripped them of all rights to participate in government and legalized debt slavery through vagrancy laws, which forced indigenous farmworkers to provide free labor for the Guatemalan government (36). The breaking point was when he issued Decree 2795, which granted landlords the authority to shoot indigenous people searching for food on private land (37).

This sets the backdrop for the October Revolution. In 1944, the largest protests in Guatemalan history erupted across the country, led by schoolteachers, students, and middle-class idealists, who demanded the end of Ubico’s regime (Schlesinger 27). They applied enough pressure on him to resign, but he was soon replaced by another strongman, General Federico Ponce (28). In response, two commanders, Major Francisco Arana and Captain Jacobo Arbenz, killed their superior officers and coordinated attacks against police and military stations to force Ponce to flee the country (31). Then, the first democratic elections took place, and Dr. Juan Arévalo was overwhelmingly elected as President of Guatemala (32). President Arévalo implemented necessary reforms, including the establishment of the first Social Security Law, the creation of a Labor Code, and the implementation of some land use reform (38-41). However, he did not attempt to make any “radical” changes that would anger the West. His successor, President Jacobo Arbenz, was left to make some of the more transformational changes to support Guatemala’s economic development.

“Guatemala, man carrying harvested bananas on plantation.” AGSL Digital Photo Archive – North and Central America. University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries. Accessed April 15, 2025. https://collections.lib.uwm.edu/digital/collection/agsnorth/id/6220/rec/63..

When Arbenz took the presidency, land reform remained a major issue. Landowners and American corporations, such as United Fruit, still owned approximately 70% of the land in Guatemala (Schlesinger 50). This was especially important for the working class, as 90% of workers worked in agriculture (54). In 1953, Arbenz enacted Decree 900, which expropriated all uncultivated land from large plantations to give to landless peasants (55). This program provided 100,000 families with a total of 1.5 million acres to use to cultivate crops and sustain themselves (55). The United Fruit Company was particularly threatened by this program and worked to convince the United States government that Arbenz was a danger to national security (77).

Through the guise of the Cold War, the State Department began planning the overthrow of Arbenz, codenamed Operation PBSUCCESS (Gonzalez 135-137). The United States and the United Kingdom collaborated on an anti-communist propaganda campaign aimed at rallying conservative Guatemalans behind U.S. intervention while also psychologically manipulating and instilling fear in the Guatemalan army, despite the military’s superior strength and broader domestic support (Moulton 2021). The State Department funded, trained, and armed political exile Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas and a disorganized group of mercenaries to conduct a coup d’état against Arbenz (Schlesinger 128- 129). After fifteen days of sporadic attacks and bombings in Guatemala, Arbenz resigned (199).

In his last speech, Arbenz said, “Workers, peasants, patriots, my friends: the people of Guatemala: Guatemala is enduring a most difficult trial. For fifteen days a cruel war against Guatemala has been underway. The United Fruit Company, in collaboration with the governing circles of the United States, is responsible for what is happening to us…One day the obscured forces which today oppress the backward and colonial world will be defeated” (Arbenz 1954).

Contemporary

The U.S.-backed coup d’état in Guatemala was followed by oppressive military dictatorships and a genocidal campaign against the Maya that endured for thirty-six years. As previously mentioned, approximately 200,000 Maya and peasants were massacred during this period. Despite the scale of these atrocities, neither the United Fruit Company—now known as Chiquita—nor any U.S. state officials have been charged for their war crimes. While former U.S.-backed dictator Efraín Ríos Montt was convicted of genocide by a Guatemalan court for the murder of tens of thousands of Ixil Maya, this remains a rare instance of justice in a broader context of impunity (Kahn 2013).

The consequences of this genocidal violence extend far beyond the staggering death toll: it led to the mass displacement of Indigenous communities, forcing many to flee their ancestral lands in search of safety and survival. Entire villages were razed, and survivors were often left with no choice but to migrate, a reality that continues to shape immigration patterns today. When we examine contemporary immigration from Central America, we must recognize the historical role of the United States in destabilizing these nations through imperialist interventions and economic exploitation.

This legacy of violence and exploitation did not end with the Cold War. Both the United States and the United Kingdom have continued to exert neocolonial control over Guatemala and Jamaica through the banana trade and the imposition of neoliberal economic policies, particularly through the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) dispute panels. The United Kingdom had historically given “imperial preference” to its former colonies to support the economies of the African, Caribbean, and Pacific (ACP) countries. However, under increasing pressure from the United States and Latin American banana exporters, this system of trade preference became a battleground during the GATT and World Trade Organization (WTO) disputes of the 1990s. Latin American growers were strategically positioned against Caribbean producers, even though both faced exploitation from the West through the banana trade.

As Peter Clegg explains, the U.S. framed its case around Latin American interests, yet its underlying goal was to exert neocolonial influence over the smaller, economically vulnerable ACP states (Clegg 2001). ACP countries were deliberately sidelined during the GATT panel hearings, lacking proper representation in decisions that directly shaped their economic futures. As Clegg argues, “The ACP interests became outsiders within the WTO not through choice, but through design” (Clegg 250). This exclusion reflected how international institutions exert economic control through the liberalization of trade.

Despite this, Caribbean nations like St. Lucia and Dominica actively resisted these maneuvers, stalling the implementation of U.S.-favored trade reforms and exposing the strategic tensions in the banana conflict (Clegg 248). Their resistance delayed U.S. efforts to fully dismantle the EU’s preferential treatment of ACP bananas (248). Yet, the final agreement, prompted by WTO rulings, pushed the European Union toward an increasingly liberalized banana market, which disproportionately harmed Caribbean producers already struggling with small economies of scale and high production costs (Courtman 2004). The long-term consequence of this shift is a market environment in which Caribbean growers are unable to compete, undermining their agricultural sovereignty and reinforcing their dependency on imperialist powers.

Together, these histories reveal how Western imperialism, perpetuated through violent political interventions and neocolonial trade systems, has had devastating lasting consequences on the economic and political infrastructures of Guatemala and Jamaica through mass displacement, the erosion of sovereignty, and the underdevelopment of these countries.

Document Analysis and Historical Synthesis

By examining five pivotal periods in Guatemalan and Jamaican history, I have identified recurring strategies employed by both the United States and the United Kingdom. In this section, I trace a shared genealogy between Guatemala and Jamaica through the lens of the banana trade, drawing on historical records and trade documents to deepen my analysis and substantiate my findings. Central to this inquiry is the question: How have Western imperialist forces collaborated to destabilize nations and maintain economic domination in Latin America and the Caribbean through the banana trade?

Racial division of labor

Through my examination of the history of colonization and slavery in Guatemala and Jamaica, I demonstrate how the development of capitalism was built upon the tortured flesh of Africans and Indigenous peoples. As Peruvian Marxist José Carlos Mariátegui observed, “The economic interests of the Spanish colonies and of the capitalist West coincided exactly,” relying on the enslavement and unpaid labor of African and Indigenous peoples to extract the raw materials that fueled Western development (Mariátegui 1971). To justify this super-exploitation, Europeans constructed race and racism, imposing a colonial racial division of labor that became foundational to the capitalist system (Quijano 538).

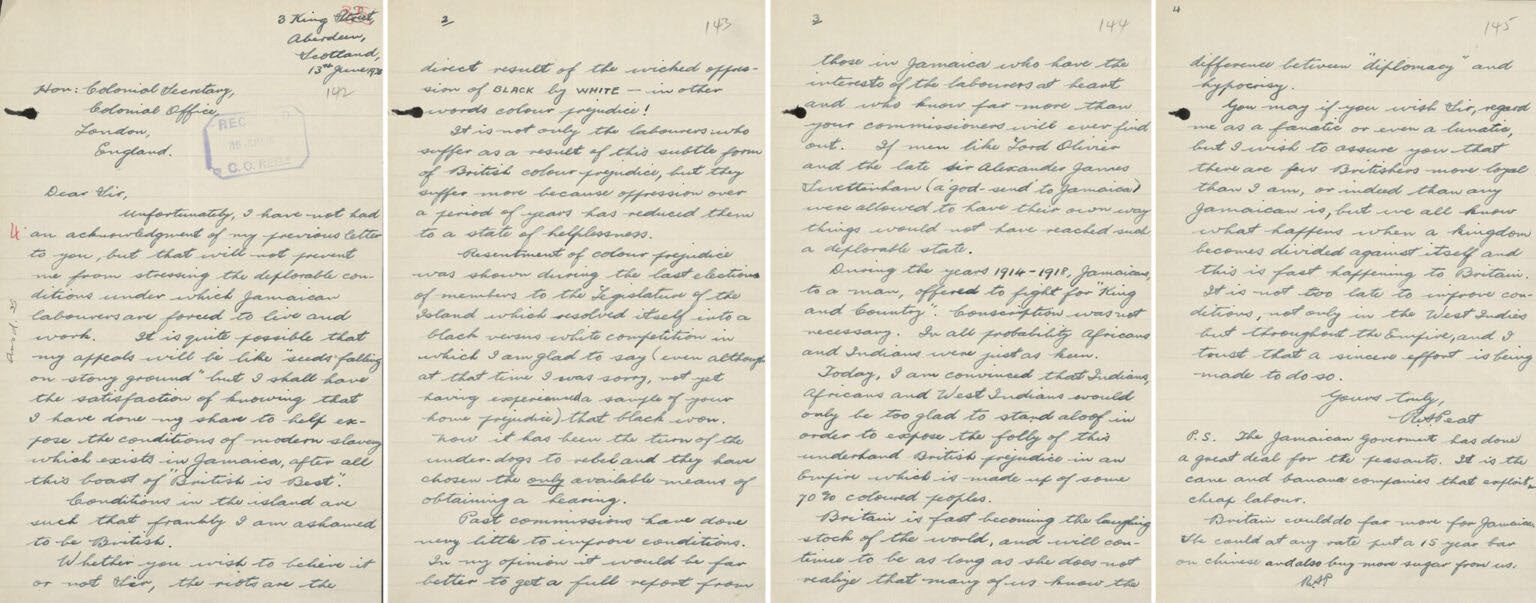

R. S. Peat’s letter to the Colonial Office in London, 1938. Catalogue ref: CO 137/827/1, The National Archives, Kew.

My research in the UK National Archives yielded a striking letter written by an individual named R. S. Peat who wrote to the Colonial Office in London from Aberdeen, Scotland about the “deplorable conditions” of Jamaican laborers. Although little is known about R. S. Peat, his letter gives some insight into how slavery and colonization has structured the division of labor to superexploit Black Jamaicans. Peat begins his letter by talking about the “conditions of modern slavery” in Jamaica that made him “ashamed to be British.” He describes the racial oppression that Jamaican laborers experienced at the hands of the British and the importance of understanding that their suffering was due to “oppression over a period of years [that] has reduced them to a state of helplessness.” Towards the end of Peat’s letter, he calls on the Empire to improve the conditions of Jamaican laborers and specifically take action against “the cane [sugar] and banana companies that exploit cheap labour.”

Although this letter is riddled with colonial language (Jamaicans were not helpless), it does illustrate how, through colonization and the development of capitalism, the United Kingdom systematically maintained a racial division of labor to keep Jamaicans exploited and Jamaica underdeveloped. This is also true for Guatemala, where the United States and American corporations imposed a racial division of labor to justify the exploitation of indigenous workers through the latifundio system.

Explicit means of control (coup d’état) and economic or monetary means of control (aid, SAPs)

The United States and the United Kingdom have both asserted control through explicit and economic means to fulfill their imperialist ambitions in the Global South. In Guatemala and Jamaica, these neocolonial tactics have had devastating consequences for the economic and political conditions of these countries. Kwame Nkrumah says, “The essence of neo-colonialism is that the State which is subject to it is, in theory, independent and has all the outward trappings of international sovereignty. In reality its economic system and thus its political policy is directed from outside” (Nkrumah ix).

One of the most glaring examples of neocolonial control is the 1954 coup d’état in Guatemala. The CIA has declassified telegrams from Operation PBSUCCESS that demonstrate how and why the CIA orchestrated a coup against Arbenz. Through my research in the State Department Archives, I located a telegram that reveals how the United States invoked anti-communism to justify the overthrow of Arbenz, aiming to maintain control over the Panama Canal and safeguard the interests of the United Fruit Company.

Telegram From the Central Intelligence Agency to the CIA Station in [place not declassified]/1/ Washington, June 27, 1954, 2251Z.

“Finally, and to repeat, this is a very serious business. The stakes are not the dividends of the United Fruit Company. The stakes are whether or not imperial Communism shall have a tactical command post in Central America within a few miles of the Panama Canal and in position undermine neighboring states. Instead of yelling about Yankee imperialism and invasion the free world should be grateful that a handful of brave but maybe pathetically comical exiles got the pitch and decided to do something about it” (Central Intelligence Agency1954).

The CIA was directed to disseminate propaganda denying any involvement by the United Fruit Company in the operation, portraying it instead as the work of ‘pathetically comical exiles’ who had independently ‘decided to do something about it’ (Schelsinger, 203). In later telegrams, it becomes clear that is not the case as the CIA explicitly makes orders to bomb Guatemalan buildings, reveals their strategy to psychologically manipulate Guatemalan soldiers, and criticizes Arbenz for his agrarian reform and the harm it has done to US companies (CIA 1954).

This case, along with Britain’s implementation of structural adjustment programs in Jamaica, underscores how both imperialist countries have leveraged violence, propaganda, economic dependency, and political intervention as interchangeable tools to maintain dominance and suppress resistance across Latin America and the Caribbean.

“Divide and conquer”: Pitting colonized nations and peoples against each other

Through my research of WTO online archives, I found key documents that showed how trade policy was used as a tool by the United States and the United Kingdom to perpetuate division among Latin American and ACP countries, with American corporate interests playing a central role (WTO Panel Report 1997). Although the EC’s preferential treatment of ACP countries reflected historical colonial ties, it was the United States — acting on behalf of powerful fruit multinationals like Chiquita and Dole — rather than Latin American governments themselves, that led the challenge to this system. The Panel concluded that the “European Communities’ banana import regime and the licensing procedures for the importation of bananas in this regime are inconsistent with the GATT 1994” (WTO Panel Report 1997). However, the real driver of this complaint was not a commitment to fair trade for Latin American nations, but the economic losses experienced by U.S.-based corporations that operated banana plantations across Central America. These American corporations and the United States effectively co-opted Latin American states into acting on their behalf at the WTO.

This dynamic underscores how imperialist powers manipulate former colonies into conflict with one another, maintaining control by preventing unified resistance. The Latin American states, though positioned as sovereign actors in the dispute, were largely speaking for the interests of foreign capital rather than their own people. The banana trade dispute illustrates this perfectly: instead of forging alliances with the ACP bloc—countries with shared colonial histories and experiences of economic marginalization—Latin American governments were instrumentalized to challenge those very preferences that aimed to support other Global South economies. The United States and United Kingdom did not and do not have the best interests of these regions at heart; rather, they continue to orchestrate divisions that keep former colonies dependent, fractured, and exploitable within the global trade system. Unity among ACP and Latin American countries could have posed a serious threat to the dominance of corporations like Chiquita and the global economic order they benefit from—but such unity was exactly what imperialist nations sought to prevent.

This thesis has traced the historical entanglements of Guatemala and Jamaica to reveal how the United States and the United Kingdom have employed shared imperialist strategies to destabilize both nations. Through the enforcement of a racialized division of labor, they created oppressive economic conditions rooted in slavery and colonization. They maintained their dominance through direct and indirect means—using coups, foreign aid, and structural adjustment programs to undermine sovereignty and suppress reform. Finally, they perpetuated division among colonized nations by manipulating trade systems and pitting nations in the Global South against one another.

CONCLUSION

This research began with a personal reckoning—with the silence of my father’s trauma and with the unanswered questions that led me to the history of U.S. intervention in Guatemala. What I uncovered was not just a singular injustice but a pattern—a global system of domination. Through my study of the banana trade in Guatemala and Jamaica, I traced the entangled roots of Western imperialism in Latin America and the Caribbean. I found that the same imperialist powers that orchestrated the coup against Jacobo Árbenz in Guatemala and crushed resistance in Jamaica were often working in concert, using a shared playbook of exploitation and repression.

Western imperialist countries destabilized the region by enforcing capitalism with a colonial character—a racialized division of labor designed to extract raw materials and agricultural goods while denying political and economic sovereignty to the people. They used both overt and covert strategies: military coups and violent interventions on one hand, and economic domination through aid packages, structural adjustment programs, and trade agreements on the other. And, true to a colonial logic, they deployed “divide and conquer” tactics—pitting colonized nations and oppressed peoples against one another to maintain control.

Today, we are witnessing the continuation of imperialist violence in the repression of the Palestinian liberation movement. Across the United States, students and workers are demanding an end to their universities’ complicity in genocide, only to be met with suspension, termination, surveillance, and deportation. The case of Mahmoud Khalil, arrested and detained after Columbia University willingly handed over student records to the Trump administration, is a chilling reminder of the lengths institutions will go to protect their imperialist interests. These acts of repression echo the very tactics I examined in my research—silencing dissent, criminalizing solidarity, and wielding state power to crush resistance.

And yet, in every corner of the Global South, and now on college campuses across the United States, people are refusing to be silent. Today’s movement is not an anomaly; it is a continuation of a centuries-long struggle against imperialism, colonization, and racial capitalism. From the fields of Guatemala to the plantations of Jamaica, from the Congo to Palestine, the struggles of oppressed peoples are interconnected.

This thesis is not just an academic exercise—it is an offering to that ongoing struggle. At this moment, students and workers must decide if they will allow fear to silence them or if they will be steadfast in their resolve against U.S. imperialism. In the face of repression, fear is real—but so is solidarity. And in solidarity, there is power.

In the words of Ghassan Kanafani, “Imperialism has layed its body over the world, the head in Eastern Asia, the heart in the Middle East, its arteries reaching Africa and Latin America. Wherever you strike it, you damage it, and you serve the World Revolution” (Samidoun, 2023).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arbenz, Jacobo. President Arbenz’s Resignation Speech. 1954. Guatemala. Becker, Carl L. Everyman His Own Historian. New York, Crofts & Co., 1938.

Burnard, Trevor. “Empire Matters? The Historiography of Imperialism in Early America, 1492–1830.” History Compass 5, no. 2, Mar. 2007, pp. 455–478. Accessed 27 Nov. 2019. Cartwright, Mark. “Pedro de Alvarado.” World History Encyclopedia, 7 July 2022, www.worldhistory.org/Pedro_de_Alvarado/.

Central Intelligence Agency. Foreign Relations, Guatemala 1952-1954. June 27, 1954. Box 9, Folder 3. Job 79-01025A. U.S. Department of State Archive, Washington, D.C. April 15, 2025.

Chukwudinma, Chinedu. “The Rodney Rebellion: Black Power in Jamaica – ROAPE.” Review of African Political Economy, 1 Apr. 2022, roape.net/2022/04/01/the-rodney-rebellion-black-power-in-jamaica/.

Clegg, Peter. The Caribbean Banana Trade: From Colonialism to Globalization. New York, Palgrave Macmillian, 2002.

Cortés, Hernán. “The Fifth Letter of Hernan Cortes.” Cartas y relaciones de Hernan Cortés al emperador Carlos V. Edited by Pascual de Gayangos. Paris: A. Chaix, 1866. Microfilm.

Courtman, Sandra. Beyond the Blood, the Beach & the Banana: New Perspectives in Caribbean Studies. Kingston ; Miami, Ian Randle, 2004.

Du Bois, W.E.B. Black Reconstruction: An Essay towards a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860-1880. New York, Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1935.

Ferguson, James A. “Jamaica | History, Population, Flag, Map, Capital, & Facts.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 26 July 1999, www.britannica.com/place/Jamaica/History#ref515835. Accessed 28 Apr. 2025.

Galeano, Eduardo. Open Veins of Latin America : Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent. New York, Monthly Review Press, 1971.

Gillick, Steven Scott. Life and Labor in a Banana Enclave: Bananeros, the United Fruit Company, and the Limits of Trade Unionism in Guatemala, 1906 to 1931. 1994.

González , Juan. Harvest of Empire. New York, Penguin Random House, 2000.

“Guatemala, man carrying harvested bananas on plantation.” AGSL Digital Photo Archive – North and Central America. University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries. Accessed April 15, 2025.https://collections.lib.uwm.edu/digital/collection/agsnorth/id/6220/rec/63..

Hart, Richard. Labour Rebellions of the 1930s in the British Caribbean Region Colonies: Richard Hart. London, Caribbean Labour Solidarity & Socialist History Society, 2002.

Holt, Thomas C. The Problem of Freedom: Race, Labor, and Politics in Jamaica and Britain, 1832-1938. Baltimore ; London, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

Igwe, Isaac O.C. “History of the International Economy: The Bretton Woods System and Its Impact on the Economic Development of Developing Countries.” Athens Journal of Law, vol. 4, no. 2, 20 Apr. 2018, pp. 105–126, www.athensjournals.gr/law/2018-4-2-1-Igwe.pdf, https://doi.org/10.30958/ajl.4.2.1.

Immerman, Richard. The CIA in Guatemala. Texas, University of Texas Press, 1982.

Josling, Tim, and T Geoffrey Taylor. Banana Wars: The Anatomy of a Trade Dispute. California, Institute For International Studies Stanford University, 2003.

Kahn, Carrie. “Three Decades On, Ex-Guatemalan Leader Faces Genocide Charges.” NPR, 18 Mar. 2013, www.npr.org/2013/03/18/174645182/three-decades-on-ex-guatemalan-leader-faces-genocide-charges. Accessed 27 Apr. 2025.

Kepner, Charles David, and Jay Henry Soothill. The Banana Empire: A Case Study of Economic Imperialism. New York, The Vanguard Press, 1935.

Lenin, Vladimir. Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism. 1917. Moscow, Co-operative Publishing Society of Foreign Workers in the U.S.S.R., 1917.

Mariátegui, José Carlos and Marjory M Urquidi. [7 Ensayos de Interpretación de La Realidad Peruana.] Seven Interpretative Essays on Peruvian Reality … Translated by Marjory Urquidi, Etc. 1928. Austin & London: University Of Texas Press, 1971.

Mintz, Steven. “Historical Context: Facts about the Slave Trade and Slavery.” The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, 2019, www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/teacher-resources/historical- context-facts-about-slave-trade-and-slavery.

Moulton, Aaron Coy. “How British Intelligence Destabilised Democracy in Central America.” Declassified Media Ltd, 8 Nov. 2021, www.declassifieduk.org/how-british-intelligence-destabilised-democracy-in- central-america/.

National Library of Jamaica. “Emancipation.” The National Library of Jamaica, 4 Aug. 2020, nlj.gov.jm/exhibition/emancipation/.

National Museums Liverpool. “Slavery in the Caribbean.” National Museums Liverpool, 2023, www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/archaeologyofslavery/slavery-caribbean.

Nicholas, Phillip. “Research Guides: Jamaica: Local History & Genealogy Resource Guide: Introduction.” Guides.loc.gov, 15 Nov. 2023, guides.loc.gov/jamaica-local-history-genealogy.

Nikolai Bukharin. Imperialism and World Economy. New York, Ny, Monthly Review Press, 1917. Nkrumah, Kwame. Challenge of the Congo. London, Panaf, 1967, p. x.

Nkrumah, Kwame. Neocolonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism. London, Panaf, 1965.

Oglesby, Elizabeth. “Great Was the Stench of the Dead.” The Guatemala Reader: History, Culture, Politics, Duke University Press, 2011.

Parker, N. A. “The United Fruit Company in Jamaica.” The Jamaica Review, vol. 1, no. 2, 1925, p. 6.

Peat, R..S. “R. S. Peat’s letter to the Colonial Office in London.” 13th June 1938. CO 137/827/1. The National Archives, Kew. April 15, 2025.

Rodney, Walter. The Groundings with my Brothers. Bogle-L’Ouverture Publications, 1969, p. 41. Rodney, Walter. How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. United Kingdom, Bogle-L’Ouverture Publications, 1972.

Samidoun. “From Ghassan Kanafani to Walid Daqqah: Assassination, Imperialism, Resistance and Revolution.” Samidoun: Palestinian Prisoner Solidarity Network, 8 July 2023, samidoun.net/2023/07/from-ghassan-kanafani-to-walid-daqqah-assassination-imperialism-resistance- and-revolution/. Accessed 28 Apr. 2025.

Schlesinger, Stephen, and Stephen Kinzer. Bitter Fruit: The Story of the American Coup in Guatemala. Cambridge (Massachusetts), Harvard University, David Rockefeller Center For Latin American Studies, 2005.

Soluri, John. “Bananas before Plantations. Smallholders, Shippers, and Colonial Policy in Jamaica, 1870- 1910.” Iberoamericana (2001-), vol. 6, no. 23, 1 June 2014, pp. 143–159, https://doi.org/10.18441/ibam.6.2006.23.143-159.

Spillers, Hortense J. “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book.” Diacritics, vol. 17, no. 2, 1987, pp. 64–81, www.jstor.org/stable/464747, https://doi.org/10.2307/464747.

United Fruit Company, “Scrapbook of United Fruit Company Photographs, 1917-1931” (1917). Select Florida Studies Manuscripts. 8. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/fl_manuscripts/8

United Nations Commission for Historical Clarification. Guatemala: Memory of Silence. United Nations, 1999.

Utsa Patnaik, et al. A Theory of Imperialism. New York, Columbia University Press, 2017. Vann, Richard T. “Historiography.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 2019, www.britannica.com/topic/historiography.

Wainer, Andrew. “Alvarado, Arbenz, Arévalo: The Repair of Guatemala.” ReVista, 28 Feb. 2024, revista.drclas.harvard.edu/alvarado-arbenz-arevalo-the-repair-of-guatemala/.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. World-Systems Analysis. Duke University Press, 2004.

Williams, Eric. From Columbus to Castro: The History of the Caribbean 1492-1969. New York , Harper & Row, Publishers , 1970.

Willis Berry, WW2 People’s War. War in Jamaica. 11 April 2005. A3880794. BBC News, Wymondham Learning Centre. https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/94/a3880794.shtml

Wolfe, Brendan. “Slave Ships and the Middle Passage – Encyclopedia Virginia.” Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities, 28 Jan. 2022, encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/slave-ships-and-the-middle- passage/.

World Trade Organization. European Communities — Regime for the Importation, Sale and Distribution of Bananas: Report of the Panel. WT/DS27/R, 22 May 1997, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds27_e.htm.