David Eccles School of Business

3 Universal Savings Accounts: Evaluating the Effectiveness of a Proposed Tax-Advantaged Savings Vehicle

Gabriel Pinna

Faculty Mentor: Scott Pickett (School of Accounting, University of Utah)

Abstract

This paper examines the effectiveness and policy implications of implementing Universal Savings Accounts (USAs) as a new tax-advantaged savings vehicle in the United States. The following research evaluates past and present legislative efforts, economic modeling, and comparative case studies of similar programs in Canada and the United Kingdom. While evidence suggests that flexible, post-tax savings vehicles can improve participation rates among low-income individuals, the paper also highlights significant fiscal trade-offs and growing concerns about regressivity. This paper concludes by arguing that any successful implementation of USAs will require careful policy calibration and bipartisan reform to balance flexibility with long-term fiscal responsibility.

Introduction

Tax-advantaged savings accounts were first introduced in the United States under the Revenue Act of 1978 and have grown substantially in number since. Under current law, there are at least 11 different types of tax-advantaged saving vehicles, each restricted to various rules, limitations, and regulations (Kaeding, n.d.). Most notable among these are retirement accounts (401ks, IRAs), education accounts (529s), and health accounts (HSAs). However, in recent years, Congress has attempted to put forth new legislation creating and adding yet another vehicle to the mix. This new savings vehicle—a Universal Savings Account (USA)—is intended to simplify the Internal Revenue Code and increase savings participation among low- and moderate-income individuals.

In their most current form, USAs are treated in a Roth-style manner, where contributions are made on a post-tax basis. Similarly, these vehicles are designed to be invested in various securities, where the returns accrued are exempt from further taxation. In general, USAs have a base annual contribution limit of $10,000, although this increases by $500 every subsequent year up until a maximum limit of $25,000 is reached. This new account, however, diverges from its well-known predecessors in that it allows penalty-free withdrawals at any time and for any general purpose.

Traditionally, individuals who make withdrawals prior to reaching a certain age or certain qualifications (subject to certain exceptions) face penalties, generally in the form of an additional tax (Internal Revenue Service [IRS], 2023). With this more lenient structure being proposed, questions as to the purpose of this account naturally arise.

Legislators who are proponents of the new vehicle argue that a USA “cuts through red tape and gives every American a flexible, tax-free way to save, invest, and spend — without government interference or penalties” (U.S. Rep. Diana Harshbarger, 2025). A special emphasis is put on those of lower socio-economic status, as the literature historically shows only a small percentage participate in currently available account options. On the contrary, critics of the account argue that USAs will ultimately increase the federal deficit and disproportionately aid those of a wealthier class in reducing their tax burden. Both arguments merit consideration and will be explored in the following sections.

It is important to note that USAs are not unprecedented, and other countries have implemented similar savings vehicles into their revenue systems. The UK, in 1999, created various tax-free savings accounts called Individual Savings Accounts (ISAs), and Canada, in 2009, enacted their Tax-Free Savings Accounts (TFSAs). Both accounts will be further analyzed to provide insight into the effects of implementing such an account in a revenue system.

Legislation

In the past 10 years, multiple bills have been introduced to create and codify USAs. In the 114th and 115th Congresses, Rep. Dave Brat [R-VA-5] introduced the Universal Savings Account Act with Sen. Jeff Flake [R-AZ] leading the companion bill in the Senate (H.R. 4094, 114th Cong., 2015). This legislation would amend the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 to allow anyone 18 years and above to open a USA and contribute up to an annual maximum of $5,500, indexed for inflation.

Additionally, in the 115th Congress, Rep. Mike Kelly [R-PA-3] introduced the Family Savings Act of 2018. Section 301 of this bill contained provisions creating USAs, nearly identical in structure to the prior bills, with a few minor amendments. The annual contribution limit was reduced to $2,500, and distributions were specified to be either cash or property readily ascertained at fair market value (H.R. 6757, 115th Cong., 2018). This bill passed the House with 240 – 177 votes but made no further progress in the Senate.

In the 118th Congress, Rep. Diana Harshbarger [R-TN-1] introduced the Universal Savings Account Act of 2024, a bill akin to those introduced in the past. This bill increased the contribution cap to an annual maximum of $10,000 (indexed for inflation) and retained the distribution provisions from the Family Savings Act of 2018 (H.R. 9010, 118th Cong., 2024). However, unlike prior legislation, this bill included provisions for phase-out thresholds for different returners based on modified adjusted gross income (MAGI): $400,000 for MFJ or QS, $300,000 for HOH, and $200,000 for all others.1 For every $1,000 of MAGI above the filing threshold limits, the annual contribution limit would be reduced by $50. The bill additionally added provisions that specified that dependents of a taxpayer cannot contribute to a USA.

Recently, in the 119th Congress, Rep. Diana Harshbarger reintroduced the previous bill with Sen. Cruz [R-TX] leading the companion bill in the Senate (H.R. 3186, 119th Cong., 2025). The 2025 version of the bill, however, has been amended to no longer contain phaseout thresholds, language specifying distribution restrictions for the account, and language prohibiting dependents from contributing to a USA. Additionally, the annual contribution limit has been altered to start at an initial base limit of $10,000, increasing in increments of $500 every subsequent year, and capping at a maximum of $25,000. This structure was referenced in the Introduction.

Literature Review

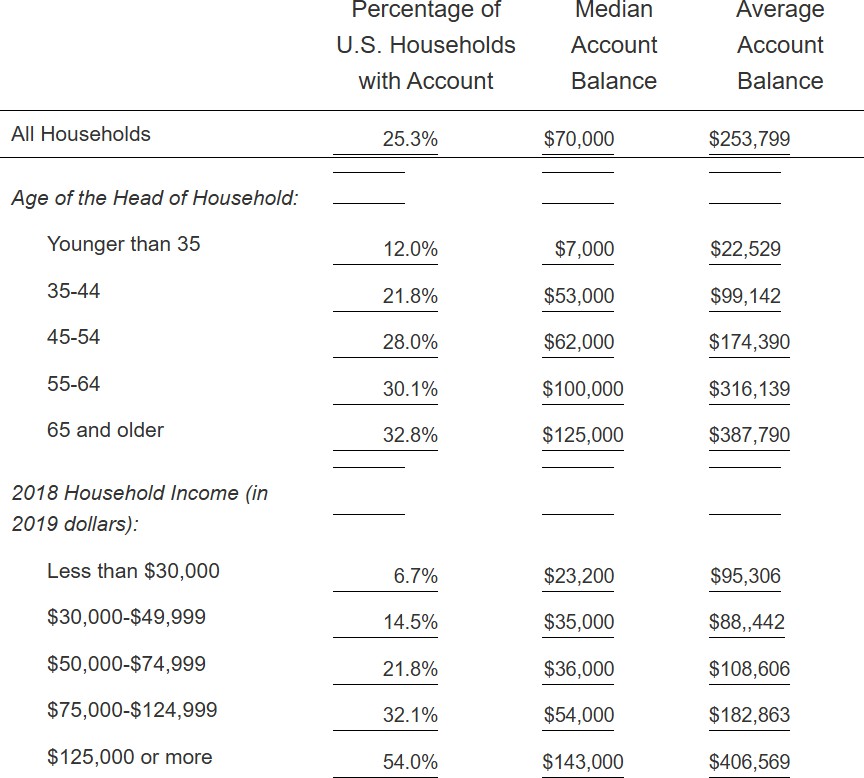

While the literature focused specifically on USAs is sparse in number, many think tanks have taken the lead in the discussion. The Tax Foundation has been most vocal regarding implementing USAs, as their analysis argues an overall net economic benefit. The institution asserts that the complexity of current accounts largely disincentivizes enrollment, especially among lower-income individuals. Data from the Congressional Research Service (CRS) analysis of the Federal Reserve’s 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) supports this claim. Only 6.7% of individuals earning under $30,000 owned an IRA, compared to 54% of those earning over $125,000 (CRS, 2020). While one cannot directly link the complexity of the current accounts to low participation rates, the data strongly suggests a correlation. Additionally, the organization points out that because current accounts require individuals to reach a certain age (59 ½) to withdraw funds penalty-free, the design dissuades those who cannot afford the illiquidity (e.g., lower-income individuals).

Source: CRS analysis of the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), Table 5

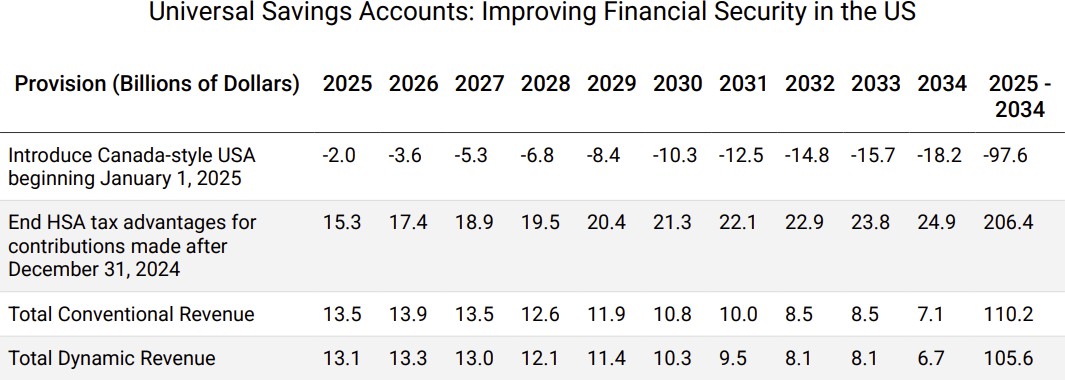

In their analysis, the Tax Foundation examined revenue effects by modeling Canadian TFSAs in the US revenue system and offsetting the fiscal costs by ending tax-advantaged contributions to HSAs (Table 1). Both changes were introduced at the beginning of 2025. The data showed a net gain of $110.2 B in conventional revenue or $105.6 B in dynamic revenue over the 10-year budget window (Tax Foundation, 2024). These revenue estimates, however, are frontloaded, meaning the initial gain will eventually be offset by losses in the future. Nonetheless, their analysis estimates that the replacement of HSAs would have a negligible effect on tax revenue in the long run. Furthermore, they assert the initial revenue gain could be used to make different policy changes that would benefit the economy through less traceable returns (e.g., reduce the deficit).

Table 1

Source: Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Model, May 2024.

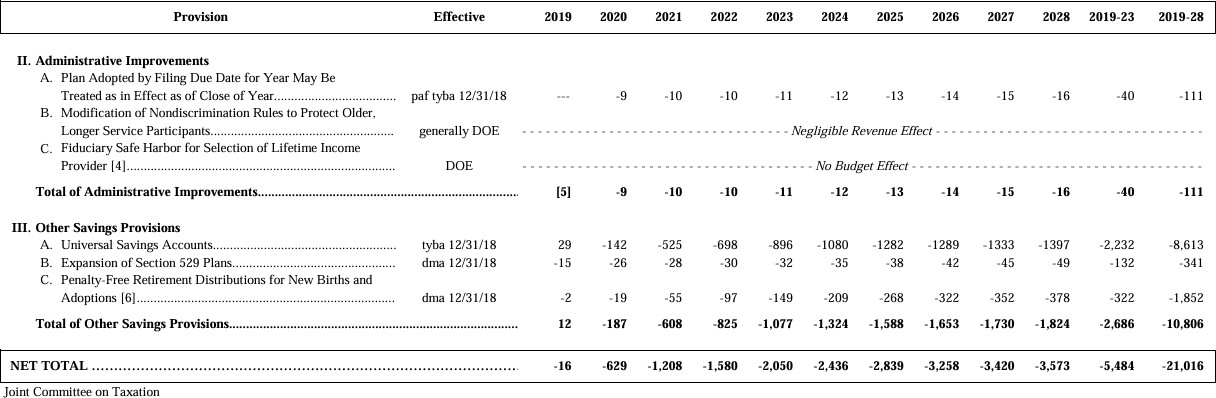

On the contrary, critics of USAs state that the new account would increase the federal deficit by encouraging individuals to shift savings out of taxable accounts. Additionally, they argue that the exemption of any phaseout provisions puts into question who these accounts are intended to benefit. In support of these concerns, the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimated federal revenue would have decreased by $8.6 B from FY 2019-2028 if USAs from the Family Savings Act of 2018 were implemented (Joint Committee on Taxation [JCT], 2018). Further concerns regarding the taxation timing (as proposed) being frontloaded also lead many to believe those estimates are artificially lowered, and in the long run, federal revenue will decline dramatically (Duke, 2018).

Source: Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Revenue Effects of H.R. 6757”

Comparative Analysis

Given the limited literature on USAs, analyzing Canadian TFSAs and the UK’s ISAs will aid in understanding how USAs may potentially impact the economy and address the claims made in the Literature Review.

Canada’s TFSAs

Tax-Free Savings Accounts (TFSAs) were introduced in Canada in 2009 to encourage Canadians to save money in a flexible, tax-advantaged account. Unlike traditional retirement accounts, the TFSA is not tied to any specific purpose, and funds can be used for a myriad of reasons: retirement, education, a home purchase, emergency expenses, etc. Regarding eligibility, individuals must be Canadian residents (with certain exceptions), no less than 18 years old, and must provide a valid Social Insurance Number (SIN). Contributions to TFSAs are made on a post-tax basis, where earnings grow tax-free and contributions are capped annually at a base of $7,000 (2025), indexing for inflation (Canada Revenue Agency, 2024). TFSAs, however, do not have a maximum cap, and unused contributions and withdrawals can be rolled over from previous years. In addition, TFSAs, like USAs, are not penalized for any withdrawals and can be invested in a variety of securities. So, what are the effects of implanting such an account?

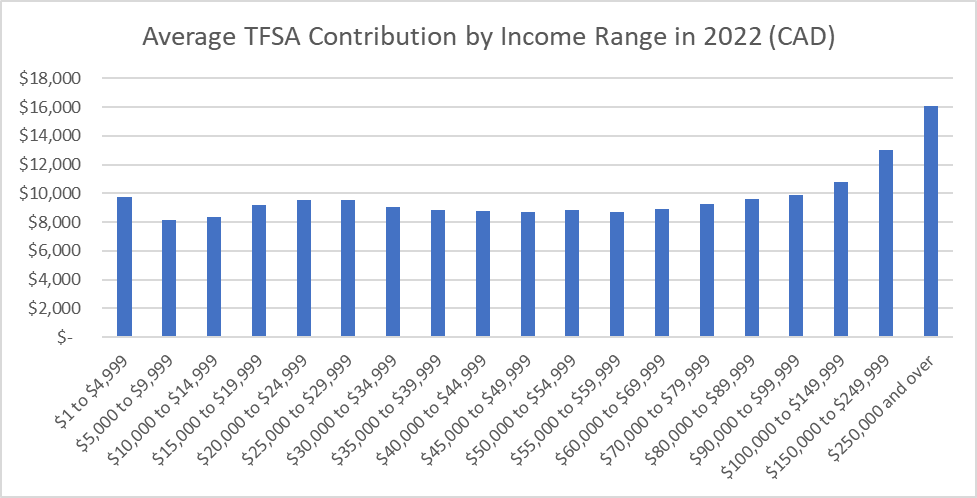

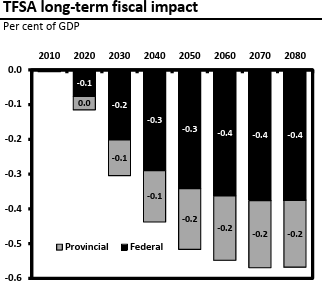

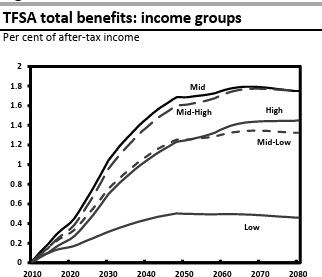

From an initial glance, the data supports the claim that these accounts benefit lower-income individuals. Data from Canada’s 2016 Census found that 26.6% of low-income (under CAD 30,000) individuals participated in TFSAs, which is substantially higher when compared to alternative retirement and pension plans (6.3% and 4.2%, respectively) (Statistics Canada, 2017). Furthermore, average contributions to TFSAs are relatively uniform across all income groups, suggesting these accounts are fairly equitable (Canada Revenue Agency, 2024).2 However, equally important to note are the fiscal impacts TFSAs have had on revenue. The Parliamentary Budget Officer estimates that in 2015, the total fiscal costs of TFSAs amounted to $1.3 B or 0.06% of GDP (Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer [PBO], 2018). By 2080, they project fiscal costs to reach 0.57% of GDP. They further note that the benefit of TFSAs will become more regressive over time, whereas those in middle to higher-income groups will ultimately benefit the most.

Source: Canada Revenue Agency, “Tax-Free Savings Account Statistics (2022 Tax Year),” Table 3C

Source: Parliamentary Budget Officer; Figures A-2 and A-3

The United Kingdom’s ISAs

Individual Savings Accounts (ISAs) were introduced in the UK in 1999 and are intended to encourage long-term, tax-efficient saving and investment among individuals. ISAs like TFSAs offer tax-free growth and penalty-free withdrawals (excluding Lifetime ISAs) and are capped at a maximum annual contribution limit of £20,000. However, differing slightly in structure from TFSAs, the UK provides four types of ISA accounts that individuals can choose from: Cash, Stocks & Shares, Innovative Finance, and Lifetime (HM Revenue & Customs, n.d.). Any interest earned from cash or income and capital gains from investments are not taxable. To be eligible for an ISA, individuals must be UK residents, no younger than 16 years old for cash ISAs, and 18 years old for stocks and shares or innovative finance ISAs. Additionally, unlike their Canadian counterpart, ISAs do not allow for unused contributions to be carried forward.

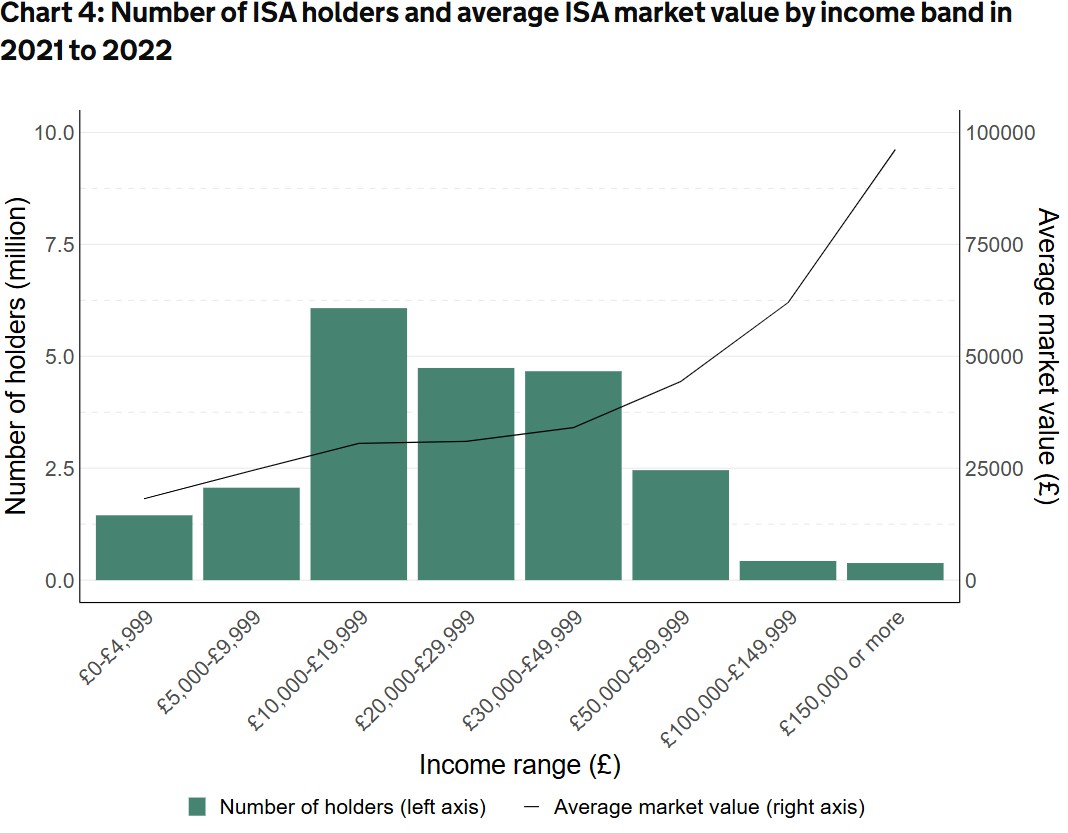

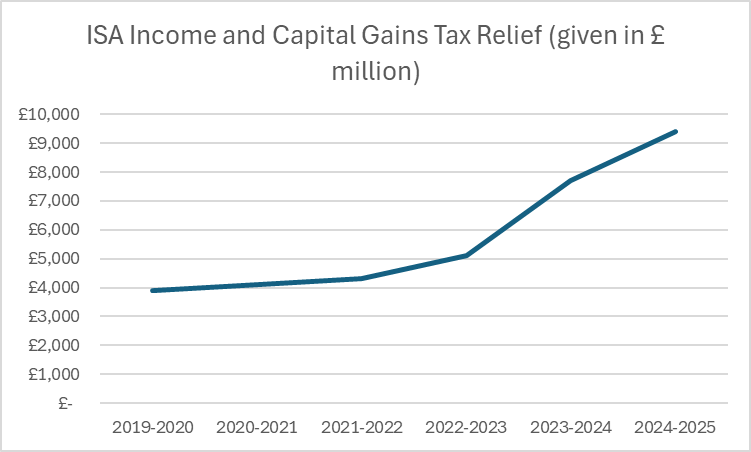

Since their introduction, the participation in savings among low-income earners has increased, with 61.3% of all ISA account holders having a gross income under £30,000 (HM Revenue & Customs [HMRC], 2020). However, as expected, these structures come with fiscal costs. In the 2023- 2024 year, ISAs cost the UK £7.7 B in revenue and are projected to cost £9.6 B in the 2024-2025 year (HM Revenue & Customs [HMRC], 2024).

Source: HM Revenue and Customs Annual Savings Statistics 2024; Chart 4

Source: HM Revenue and Customs Non-Structural Tax Relief Statistics (December 2024); Table 1

Policy Discussion

Given the data presented through comparative analysis and economic modeling, the question persists as to whether USAs should be implemented and whether these new accounts would truly be beneficial. While the data supports a correlation between lower-income participation and flexible tax accounts, the fiscal costs associated with them complicate the situation. Ultimately, the answer will remain unknown until these accounts are codified and time-series analysis can be performed. What is known, however, is that the structure of these accounts is integral to their political and budgetary implications.

USAs, in their most recent proposed form (H.R. 3186), are likely to gain little traction and bipartisan support. The increased maximum contribution limit and exclusion of income phaseout provisions alone bolster critics’ reservations towards the account. As a result, for this legislation to be successfully codified, amendments to the bill must be made to help address certain concerns from hesitant parties. One may recommend that the Universal Savings Account Act of 2024, originally introduced by Rep. Harshbarger, be used as a basis for negotiating amendments, given that the bill appears to be the most accommodating. Furthermore, potentially altering the tax treatment of USAs to follow a traditional style (pre-tax deduction) may allow the government to capture any abnormal gains in the market and help offset budgetary concerns. If the intentions of creating USAs are truly for the benefit of the people, political compromise must be at the forefront of conversations.

Conclusion

To conclude, while USAs still exist in the abstract of conversations in Washington, DC, this research serves as a tool to better understand the potential effects and considerations these accounts require. Still, much negotiation needs to be done before any hope of codification becomes realistic. Evidence from Canada’s TFSA and the UK’s ISA programs reveals that structurally similar accounts can successfully expand savings participation across income levels, especially among low-income individuals who are dissuaded by current savings vehicles. However, these gains come with measurable fiscal trade-offs, as both countries have experienced rising revenue losses associated with their implementation. To make USAs viable and equitable, future proposals must balance flexibility with fiscal responsibility. Above all, the success of USAs as a tool for financial security and tax simplification depends not only on policy design but also on the willingness of legislators to engage in meaningful, bipartisan reform.

Footnotes

1 MFJ: Married Filing Jointly; QS: Qualifying Surviving Spouse; HOH: Head of Household

2 Certain types of income are not included in total income assessed because they are non-taxable, so true economic income may be understated.

Bibliography

Kaeding, N. (n.d.). Universal Savings Accounts: A flexible, simple way to promote financial security. Tax Foundation. https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/universal-savings- accounts-financial-security/

Internal Revenue Service. (2023, December 14). Hardships, early withdrawals and loans. U.S. Department of the Treasury. https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/hardships-early- withdrawals-and-loans

U.S. Senator Ted Cruz. (2025, May 6). Sen. Cruz, Rep. Harshbarger introduce USA Act. https://www.cruz.senate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/sen-cruz-rep-harshbarger-introduce-usa- act

H.R. 4094, 114th Cong. (2015). https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/4094

H.R. 6757, 115th Cong. (2018). https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house- bill/6757/text#toc-H3D0A803B6C0C441384C15A3D6B30995E

H.R. 9010, 118th Cong. (2024). https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house- bill/9010?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%22hr9010%22%7D&s=7&r=1

H.R. 3186, 119th Cong. (2025). https://www.congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/house- bill/3186?s=2&r=1

Congressional Research Service. (2020, December 3). Saving for retirement: Household decision making and policy options (CRS Report No. R46635). https://www.congress.gov/crs- product/R46635

Tax Foundation. (2024, February 14). Universal savings accounts: Improving financial security for all Americans. https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/universal-savings- accounts-financial-security/

Joint Committee on Taxation. (2018, September 12). Estimated budget effects of the “Family Savings Act of 2018” (JCX-75-18). https://www.jct.gov/publications/2018/jcx-75-18/

Duke, B. (2018, August 14). “Universal Savings Account” proposal in House Republican tax framework is ill-conceived. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/universal-savings-account-proposal-in-house- republican-tax-framework-is-illCe

Canada Revenue Agency. (2024). Tax-Free Savings Account (TFSA), Guide for Individuals (RC4466). Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/forms- publications/publications/rc4466/tax-free-savings-account-tfsa-guide-individuals.html

Statistics Canada. (2017, September 13). Census in Brief: Household contribution rates for selected registered savings accounts. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-200-X2016013. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/98-200-x/2016013/98-200- x2016013-eng.cfm

Canada Revenue Agency. (2024, January 15). Tax-Free Savings Account statistics (2022 tax year). Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/programs/about- canada-revenue-agency-cra/income-statistics-gst-hst-statistics/tax-free-savings-account- statistics/tax-free-savings-account-statistics-2022-tax-year.html

Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer. (2018, October 16). Costing note: Revenue effect of the Tax-Free Savings Account. https://distribution-a617274656661637473.pbo- dpb.ca/68a1514c053cbb965758d718c99ae6b85f2893edfebdcf48c2f488e2079ccc9d

HM Revenue & Customs. (n.d.). How ISAs work. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/individual-savings-accounts/how-isas-work

HM Revenue & Customs. (2021, June 8). Commentary for annual savings statistics: June 2021. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/annual-savings-statistics/commentary-for-annual-savings-statistics-june-2021

HM Revenue & Customs. (2024, December 5). Non-structural tax relief statistics (December 2024). GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/main-tax-expenditures-and- structural-reliefs/non-structural-tax-relief-statistics-december-2024