Honors

151 Motivations, Expectations, and Experiences of Parents Who Take a Child to a Village Doctor With a Complaint of Diarrhea: A Qualitative Study in Rural Bangladesh

Jane Putnam; Melissa Watt; Aparna Mangadu; Jyoti Bhushan Das; Sarah Dallas; Olivia Hanson; Daniel T. Leung; and Ashraful Islam Khan

Faculty Mentor: Melissa Watt (Anthropology, University of Utah)

ABSTRACT

Background: In Bangladesh, informal healthcare providers (“village doctors”) meet the healthcare needs of the rural poor, but also contribute to inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions in rural communities. In cases of acute pediatric diarrhea, antibiotics are usually unnecessary, and inappropriate use can harm patients and contribute to antibiotic resistance. This study explored parents’ motivations and expectations for care, including antibiotics, when seeking treatment for pediatric diarrhea from a village doctor, and examined how village doctors respond to and manage these expectations.

Methods: We conducted in-depth interviews with parents who took their child to a village doctor (n = 12) and village doctors (n = 18) in Bangladesh. Analysis identified motivations and expectations of parents, and how those expectations impacted village doctor decision making.

Results: Motivating factors for seeking care from a village doctor included geographic proximity, accessibility, familiarity and trust. Parents often expected antibiotics for pediatric diarrhea treatment. Village doctors described how parents’ expectations contributed to their decision to dispense antibiotics, even if not clinically necessary.

Conclusion: Village doctors are trusted members of communities and play a critical role in meeting rural healthcare needs. Their antibiotic-related clinical decisions can play a role in antibiotic resistance rates. Educational and diagnostic interventions should target both community members and village doctors to reduce inappropriate antibiotic use in children.

INTRODUCTION

The informal healthcare sector (e.g., drug vendors, traditional birth attendants, traditional healers, and untrained allopathic providers) plays an important role in meeting the health care needs of the world’s population (Kumah, 2022) (Nayak et al., 2022). In many low- and middle- income countries (LMICs), informal healthcare providers deliver the bulk of healthcare services, especially for the rural poor (Kong et al., 2021). These providers often step in to fill the gap left by limited access to the formal healthcare sector by providing medical advice and treatment, despite lacking formal medical training (Sudhinaraset et al., 2013).

Informal healthcare providers frequently operate in environments with weak pharmaceutical regulations, resulting in large scale and unregulated antibiotic use within the community (Tandan et al., 2024) (Murray et al., 2024). While the World Health Organization suggests antibiotics may be appropriate for pediatric diarrheal disease under key circumstances (Departments of Child and Adolescent Health and Development and HIV/AIDS), unrestricted and universal antibiotic dispensing by informal providers is common in LMICs (Bashar et al., 2024). The inappropriate use of antibiotics contributes to the growing global health threat of antibiotic resistance (Murray et al., 2024).

The overuse and misuse of antibiotics by informal providers reflect a brloader global issue, as inappropriate antibiotic dispensing practices contribute to the escalating problem of antibiotic resistance (Salam et al., 2023, Llor, Bjerrum, 2014). With continued and increasing reliance on antibiotics, emergent strains of resistant bacteria begin to propagate (Salam et al., 2023). Resistance diminishes the effectiveness of these crucial medications, posing a severe threat to public health worldwide and signaling the potential onset of a post-antibiotic era where common infections may become difficult to treat(Wang et al., 2020).

In Bangladesh, informal healthcare providers that practice allopathic medicine without formal training are called “village doctors” (Mahmood SS, et al., 2010). They are a crucial component of the healthcare system, particularly for the rural poor, typically providing patient consultations and selling medications, including antibiotics (Hanson et al., 2024). Due to their lack of formal medical training and clients’ demand for quick remedies, village doctors often resort to prescribing antibiotics indiscriminately (Rasu et al., 2014), including for viral cases of pediatric diarrhea where antibiotics are not an effective treatment.

Village doctors’ antibiotic dispensing habits may be influenced by parental expectations of care for pediatric diarrhea. A study conducted in India suggests that external pressure from patients significantly influenced the antibiotic dispensing habits of informal healthcare practitioners (Khare et al., 2022), with patients often viewing antibiotics as a “quick fix” and demanding antibiotics from informal practitioners. The financial motivations of informal practitioners lead them to comply with patient demands (Khare et al., 2022). Patients and parents of pediatric patients frequently view antibiotics as a catch-all solution for various ailments, pressuring village doctors to fulfill these expectations to maintain their clientele and livelihood (Murray et al., 2024). Thus, an investigation of community attitudes and perspectives on antibiotics may provide crucial insight into the potential motivations and contributing factors for inappropriate antibiotic dispensing practices among village doctors.

Given the significant role of the informal healthcare sector in many LMICs, particularly in rural areas, it is crucial to understand the dynamics that influence clinical decision-making, including decisions related to antibiotic use. As patients and parents of pediatric patients have been shown to play a critical role in shaping providers’ clinical behavior, including antibiotic dispensing practices in other regions (Khare et al., 2022) (Murray et al., 2024), understanding the motivations and expectations of parents when they bring their children to village doctors in Bangladesh is essential. This study aims to qualitatively explore parents’ expectations when seeking care for pediatric diarrhea from a village doctor and to understand how these expectations influence village doctors’ clinical decision-making.

Methods

Overview

In-depth interviews (IDIs) were conducted with parents (n=12) who brought their child to a village doctor with the primary complaint of diarrhea to gain insights on parents’ motivations, expectations, and experiences when seeking care from village doctors. IDIs were also conducted with village doctors (n=18) to explore their perspectives of parents’ motivations and expectations, and how these influence clinical decision making.

Study Setting & Population

The study was conducted in the Sitakunda Upazila (subdistrict) of the Chattogram District in Southeastern Bangladesh. The Situkunda Upazila is comprised of about 500 square kilometers and its population consists of approximately 383,000 people (Bangladesh Local Health Bulletin, 2023). Through a community-based survey, we previously identified approximately 400 village doctors practicing in this area (Hanson et al., 2024), which served as our sampling framework.

Study participants consisted of: 1) adult parents of pediatric patients and 2) village doctors. Parents were eligible if they identified as the primary adult responsible for a child under 5 years of age that had visited a village doctor with a primary complaint of diarrhea. All caregiver participants were the biological parents of the child patients and are thus referred to throughout this paper as “parents”. Village doctors were defined as informal healthcare providers or drug vendors without medical degrees who practiced allopathic medicine outside of formal healthcare facilities.

Procedures

Face-to-face individual IDIs were conducted in June and July of 2023. Caregiver participants were approached and recruited directly from the village doctor practices and screened for eligibility. Village doctor participants were approached at their clinical work locations and invited to participate. Interviews, conducted by a member of the qualitative research team at the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b), ranged in duration from 20 to 30 minutes and were conducted in Bangla.

Semi-structured interview guides included open-ended questions and follow-up probes. The interview guide for parents of pediatric patients (Supplement 1) covered topics such as the child illness, rationale for seeking village doctor care, past experiences with village doctors, and opinions on treatment improvements. The interview guide for village doctors (Supplement 2) covered the village doctor’s role in the community, typical care provided, typical treatment for pediatric diarrhea, and personal views on pediatric antibiotic use. IDIs with village doctors also focused on their perceptions of parents’ expectations and how they manage these expectations in their clinical practice. All IDIs were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and translated into English for analysis.

Analysis

An applied thematic analysis framework (Guest et al., 2012) guided the analysis of the IDIs, aimed at developing a nuanced understanding of parents’ motivations, expectations, and experiences when taking a child for care from a village doctor. The analysis involved several stages: familiarization with the raw data, coding, identification of emerging themes, extracting, analytic memo writing, and interpretation of the data.

Analysis was conducted in NVivo (ver 12). We developed a codebook to identify emerging themes across three domains: 1) parents’ motivations for seeking village doctor care, 2) parens’ expectations of village doctors, and 3) village doctors’ perspectives of parental expectations and influence on clinical decision making. Once coding was completed and emerging themes were identified, analytic memos were written to develop a comprehensive understanding of the data and identify representative quotes for the emerging themes.

Ethics

This study was approved by the ethics board of both the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (iccdr,b) and the University of Utah. Participants provided written consent to participate in the study and did not receive financial compensation beyond transportation reimbursement.

Results

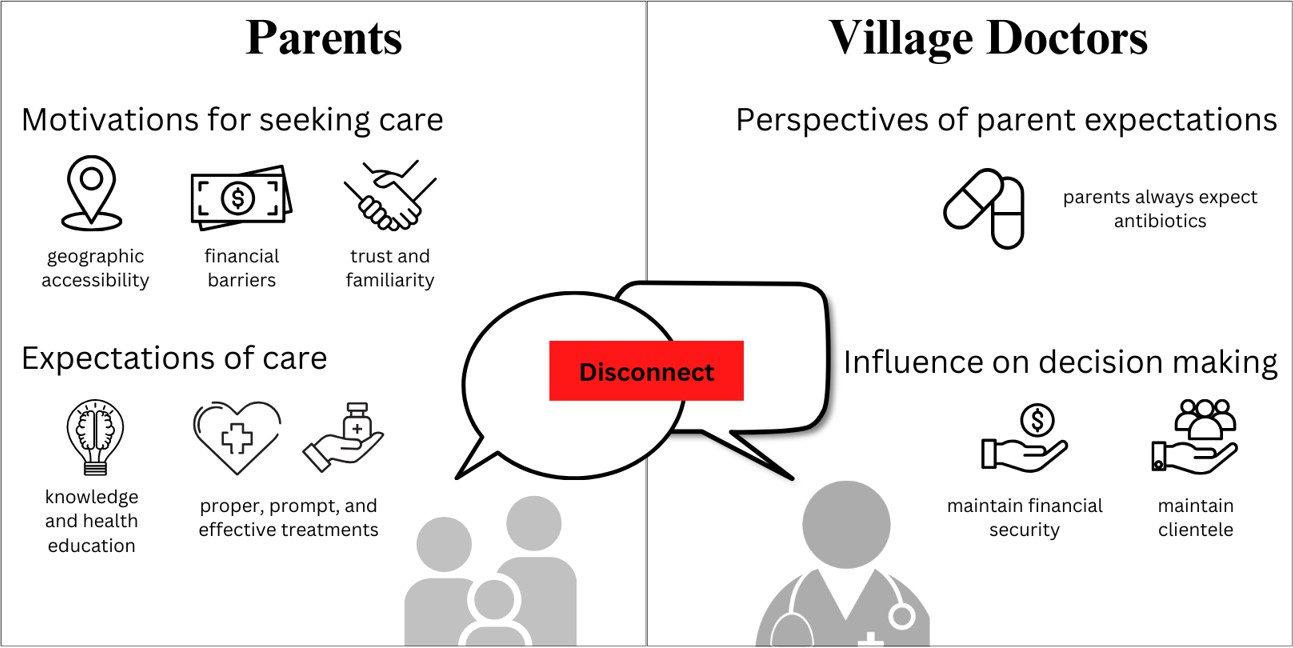

The 12 pediatric parents included both mothers (n=9) and fathers (n=3). The average age of parents was 29 years (Range: 18-40 years). Village doctor participants (n=18) were all male, with an average age of 41 years (Range: 28-63 years). Figure 1 illustrates the thematic findings related to parent motivations and expectations, and the influence on village doctor care.

Parents’ Motivations for Seeking Village Doctor Care

Three themes emerged that characterized parents’ motivations for seeking care for their child from a village doctor: 1) geographic accessibility, 2) financial accessibility, and 3) trust in and familiarity with village doctors.

Geographic accessibility

Since Bangladesh offers government funded healthcare services through hospitals and MBBS (Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery) doctors, parents of patients may seek care from either trained practitioners or village doctors. While parents acknowledged that government hospitals with trained healthcare workers provide higher quality of care, they primarily visited village doctors as the first point of care for pediatric diarrhea.

“If the fever or cough is not getting better by the medicine provided by Dr A, then I visit hospital for better treatment by the specialized doctors. I also need to go to the hospital to diagnosis. Few days ago, my younger son was suffering from fever and sore throat. He was unable to breastfeeding. At the very first, I consult with Dr A and gave him medicine. But he was not improving. Then I managed some money and visit a child specialist in sitakundo. With that medication, he was cured.” (Mother of a 16-month-old, living in the community for 16 years)

Parents often mentioned geographic barriers to seeking care in formal health facilities. They mentioned the time and cost it takes to travel to a formal healthcare facility, general difficulties with transportation, and appreciation that village doctor performed house calls. Given the rural nature of the study setting, limited transportation and the time commitment associated with visiting a government hospital were strong deterrents from seeking care at these locations unless serious care is required.

“The truth is, distance matters. The hospitals are not too far from here, but the VD’s chamber is walking distancefrom here.… It feels inconvenient to go to the hospital as it takes almost one hour to reach.”(Father of a 3-year-old, living in the community for 4 years).

Another key difference between MBBS doctors and village doctors is accessibility via house calls. Village doctors often live and work locally which allows them the flexibility to preform house calls. Parents expressed gratitude towards these house calls.

If we go to a hospital at night then we will not get a doctor. They will say [MBBS] is not available even despite being available. That’s why we visit [a village doctor]. He visits home if needed. Other doctors (MBBS) will not come at home. [The village doctor] is good for us.” (Mother of a 3-year-old, living in the community for 6 years).

Financial accessibility

Financial restraints also play a significant role in the decision to seek care from a village doctor. Parents indicated the lesser cost of village doctor care, compared to a MBBS doctor in a hospital facility.

“He gives good advice, and his medicines work. We don’t need to go to the doctor outside our village/community or in the farthest area. [The village doctor] gives the same medicines, an MBBS doctor or specialist doctor gives. If [the village doctor] gives the same medicines then why should we go to a big doctor (MBBS)? The medicines of a doctor with 800TK fees and the medicine of [the village doctor] are the same. We visit other doctors as well if the situation becomes so critical.” (Mother of a 3.5-year-old).

Trust and confidence in village doctor care

Trust and familiarity with village doctors played an important role in the decision to seek care at a village doctor practice. Parents who had received care from a village doctor in the past felt comfortable with continuing to utilize them as a resource for care for their children. Families typically all visit the same village doctor, forming generational connections. A close and trusted relationship between the family and the village doctor was cited as being among the most important motivations to continue returning to the same practitioner.

“Now the point is that I have been seeing Dr A here for treatment since my birth. In addition to this, all of our family took treatment from him. People go to others too, but actually I like him so I go to him. Apart from this, the effectiveness of medicine also works here.” (Father of a 1.6-year-old, living in the community for 20 years)

Parent Expectations of Village Doctors

Three themes emerged regarding parents’ expectations during a visit to a village doctor: 1) health education and understanding of health conditions, 2) proper treatment, and 3) effective medications.

Health education and understanding of health conditions

When visiting a village doctors, parents explained that they expected to get information about their child’s health condition and a specific diagnosis. Specifically, they expected that the village doctor would take into account the patient’s medical history, symptoms, and parental concerns in order to fully understand the health status and move forward with appropriate treatment.

“The medicines that he prescribes work well in our body. The main thing is that if a doctor can diagnose the diseases, then he can be able [to] give them better treatment. So, in terms of understanding a patient’s problems, I think he is a good doctor.” (Father of a 3-year-old, living in the community for 4 years)

Proper treatment

Proper and prompt treatment was also noted as an important expectation of parents. Participants expressed that the treatment received from village doctors will provide quick resolution of symptoms and more timely recovery.

“Her fever decreased, and the diarrhea stopped. Just one day has passed since the medicines were given. He [VD] gave us the medicine the other day.” (Father of a 3-year-old, living in the community for 38 years)

Effective medications

The receipt of effective and essential medications was also an important expectation held by parental caregivers. Parents describe “effective medications” as those that work quickly with limited side effects. Parents noted that the majority of medications that patients received were antibiotics. However, parents did not explicitly state that they expected to receive antibiotics from a village doctor, just that they expected medications to work quickly and properly.

“I went to him [VD] because I expected to get well by taking medicine from him without buying medicine from the [MBBS] doctor again and again.”(Father of a 1.6-year-old, living in the community for 20 years)

The baby had soft stool two/three times, (VD) give medicines so that it recovers. The doctor gave some medicines and told try these medicines if not improve then antibiotics will be provided. If the condition becomes improve or is cured we usually don’t revisit the doctor. (Mother of 3-year-old, living in the community for 6 years)

Village Doctors’ Perspectives of Parental Expectations and Influence on Clinical Decision Making

The village doctor IDIs identified themes surrounding: 1) village doctors’ perspectives on parent expectations, and 2) how parental expectations influence course of care.

Village doctors’ perspectives on parent expectations

Village doctors said that parents often come to their shop with set expectations regarding care and treatment. Village doctors indicated that expectations held by parents have an impact on how they proceed with providing care.

“They [parents] expect powerful antibiotics. Usually, if there is not need to give antibiotics, [parents] force us to give one” (Village doctor, 28 years old)

How parental expectations influence course of care

Village doctors explained how the explicit and implicit expectations of parents led them to sell antibiotics. They said that village doctors will sell antibiotics in order to maintain long-term financial security.

“Yes, some of the VDs are involved in selling medicines. That’s the problem. So for better profit margins, some of them are prescribing and selling excess antibiotics.” (Village doctor, 47 years old, 22 years of experience)

Village doctors also noted that appeasing parents and maintaining clientele are additional factors in their decision-making practices. Practitioners will supply antibiotics when they feel pressure from a patient or patient caregiver, for fear of them finding business elsewhere.

“They say, give me the best antibiotics, no matter what it costs. If I try to motivate them and advise them not to do so, they leave my shop and go to another.” (Village doctor, approx. 19 year of experience)

“Some patients will recover without antibiotics for 7 days, but they (the patient or parent of patient) cannot tolerate this. So, if I do not give them, he will go to the other doctor; they will provide the antibiotics, and in the meantime, he will recover quickly. For this, I become bad, and that doctor becomes good for providing the antibiotics.” (Village doctor, age and experience not specified)

Discussion

Inappropriate dispensing of antibiotics within the informal healthcare sector of LMICs is an important factor contributing to the ongoing threat of antibiotic resistance (Tandan et al., 2024). These unregulated prescription habits have previously been linked to patient expectations regarding antibiotic care (Murray et al., 2024). Understanding why parents take their children to village doctors and what they expect from the clinical encounter is important to provide a full understanding of the drivers of antibiotic misuse (Kotwani et al., 2010, Mangione-Smith et al., 1999). This study aimed to analyze parents’ motivations and expectations surrounding a visit to a village doctor, and how these factors can influence antibiotic dispensing practices in Bangladesh.

Factors such as location, price, and trust all contributed to parents bringing their children to village doctors. Parents expected village doctors to be knowledgeable, prompt and provide effective treatment, including antibiotics. Village doctors in turn stated that they felt pressure to prescribe antibiotics because of the expectations set forth by parents. This pressure is echoed throughout studies in the United Kingdom and West Bengal, India, where clinicians (with varying levels of medical training) felt that patient expectations surrounding treatment affect their antibiotic prescription habits (Cole et al., 2014, Nair et al., 2019). These globally recognized trends demonstrate the importance of formal medical training and health education for both informal providers and the broader community.

Previous studies exploring the healthcare dynamics of LMICs note that informal providers typically fill gaps in healthcare left by poor access to trained doctors and government funded hospitals (Sudhinaraset et al., 2013). In our study, parents noted that geographic accessibility is among the main reasons they opt to visit an untrained village doctor over a clinician at a government hospital. As village doctor become more accessible to lower income communities, their patient load is likely to increase. However, increased rates of patients seeking village doctor care places a large burden of care on these untrained practitioners (Sudhinaraset et al., 2013). It is important to recognize the value of informal providers and the accessible healthcare they can provide, while also advocating for additional training and diagnostic tools to aid in clinical care.

Perspectives of both parents and village doctors suggest the importance of improved health education for both parties. Many parents expressed their understanding of antibiotics as a more powerful medication, but did not necessarily expect or want antibiotic prescriptions. Parents also solely expressed their desire for “effective” medications, regardless of the type. Additionally, most parents indicated that they typically trusted the diagnoses received from village doctors and followed their treatment recommendations. While these findings suggest that parents don’t necessarily visit a village doctor with the expectation of receiving antibiotics, many village doctors believed that caregivers expected antibiotics, regardless of village doctor recommendation or diagnosis. There is a clear disconnect between caregiver expectations and village doctors’ understanding of these expectations. This miscommunication could potentially be addressed with increased health literacy initiatives and educational tools aimed at antibiotic stewardship and the dangers of antibiotic resistance (Hunter, Owen, 2024).

Past literature confirms the benefits of educational tools for parents, aimed at expanding their understanding of antibiotics and the dangers associated with their misuse (Taylor et al., 2003, Trepka et al., 2001, Hunter, Owen, 2024, Khan et al., 2024). Our findings demonstrate that parents rely heavily on village doctors and typically defer to their judgement regarding what an “effective” prescription is, demonstrating the value of increased health education for these untrained providers. Given the community-wide level of trust in village doctors, as expressed by parents of pediatric patients, they are clearly a valued aspect of the Bangladeshi healthcare system and should be trained and utilized to the highest possible level.

There are several limitations of this study to consider when interpreting these results. The study includes a relatively small sample with only twelve caregiver and eighteen village doctors. The sample is limited to a small rural region, restricting our ability to generalize our findings and adapt them to a broader population. It is also important to note that human antibiotic use is not the only factor contributing to the global antibiotic resistance crisis, and that antibiotic use in agriculture and livestock production plays a large role in the ongoing resistance problems we see today (Salam et al., 2023).

Conclusions

The results of this study indicate a need for future investigations surrounding factors leading to rising antibiotic resistance threats, particularly within the informal healthcare sector of LMICs. In LMICs with large informal healthcare sectors, it is important to acknowledge the impact that these untrained providers can have on broader and global public health concerns. Parent motivations and expectations are among many influential reasons for changes in informal practice habits. These changes can contribute to higher rates of unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions, which can play a key role in rising antibiotic resistance crises. The findings of this study can additionally inform health education interventions that will address the communication gap identified between healthcare providers and patients.

Figure1: Interview data themes regarding caregiver motivations and expectations, and village doctor perspectives

Bibliography

Anwar, M., Raziq, A., Shoaib, M., Baloch, N. S., Raza, S., Sajjad, B., Sadaf, N., Iqbal, Z., Ishaq, R., Haider, S., Iqbal, Q., Ahmad, N., Haque, N., & Saleem, F. (2021). Exploring Nurses’ Perception of Antibiotic Use and Resistance: A Qualitative Inquiry. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 14, 1599–1608. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S309020

Baral, R., Nonvignon, J., Debellut, F., Agyemang, S. A., Clark, A., & Pecenka, C. (2020). Cost of illness for childhood diarrhea in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of evidence and modelled estimates. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 619. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08595-8

Bashar, S. J., Islam, M. R., Nuzhat, S., Amin, R., Rahman, M. M., Pavlinac, P. B., Arnold, S. L. M., Newlands, A., Ahmed, T., & Chisti, M. J. (2024). Antibiotic use prior to attending a large diarrheal disease hospital among preschool children suffering from bloody or non-bloody diarrhea: A cross- sectional study conducted in Bangladesh. PloS One, 19(11), e0314325. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0314325

Bloom, G., Standing, H., Lucas, H., Bhuiya, A., Oladepo, O., & Peters, D. H. (2011). Making health markets work better for poor people: the case of informal providers. Health Policy and Planning, 26(suppl_1), i45–i52. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czr025

Chandy, S. J., Mathai, E., Kurien, K., Faruqui, A. R., Holloway, K., & Lundborg, C. S. (n.d.). Antibiotic use and resistance: perceptions and ethical challenges among doctors, pharmacists and the public in Vellore, South India. Indian Journal of Medical Ethics. Retrieved February 7, 2025, from https://ijme.in/articles/antibiotic-use-and-resistance-perceptions-and-ethical-challenges-among- doctors-pharmacists-and-the-public-in-vellore-south-india/?galley=html

Cole, A. (2014). GPs feel pressurised to prescribe unnecessary antibiotics, survey finds. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g5238

Departments of Child and Adolescent Health and Development and HIV/AIDS (CAH). (n.d.). WHO recommendations on the management of diarrhoea and pneumonia in HIV-infected infants and children. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/44471/9789241548083_eng.pdf;sequence=1

Global Burden of Disease Pediatrics Collaboration, Kyu, H. H., Pinho, C., Wagner, J. A., Brown, J. C., Bertozzi-Villa, A., Charlson, F. J., Coffeng, L. E., Dandona, L., Erskine, H. E., Ferrari, A. J., Fitzmaurice, C., Fleming, T. D., Forouzanfar, M. H., Graetz, N., Guinovart, C., Haagsma, J., Higashi, H., Kassebaum, N. J., … Vos, T. (2016). Global and national burden of diseases and injuries among children and adolescents between 1990 and 2013: Findings from the global burden of disease 2013 study. JAMA Pediatrics, 170(3), 267–287. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4276

Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. (2023). Local Health Bulletin. Guest, G., M.MacQueen, K., & E.Namey, E. (n.d.). Sage Research Methods – Applied Thematic Analysis – Introduction to Applied Thematic Analysis. Retrieved February 3, 2025, from https://methods.sagepub.com/book/mono/applied-thematic-analysis/chpt/introduction-applied- thematic-analysis

Hanson, O., Khan, I. I., Khan, Z. H., Amin, M. A., Biswas, D., Islam, M. T., Nelson, E. J., Ahmed, S. M., Brintz, B. J., Qadri, F., Watt, M. H., Leung, D. T., & Khan, A. I. (2024, September 13). Identification, mapping, and self-reported practice patterns of village doctors in Sitakunda subdistrict, Bangladesh. JOGH. https://jogh.org/2024/jogh-14-04185/

Holloway, K. A., Kotwani, A., Batmanabane, G., Puri, M., & Tisocki, K. (2017). Antibiotic use in South East Asia and policies to promote appropriate use: reports from country situational analyses. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j2291

Hunter, C. R., & Owen, K. (2025). Can patient education initiatives in primary care increase patient knowledge of appropriate antibiotic use and decrease expectations for unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions? Family Practice, 42(2), cmae047. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmae047

Khan, I. I., Hanson, O. R., Khan, Z. H., Amin, M. A., Biswas, D., Das, J. B., Munim, M. S., Shihab, R. M., Islam, M. T., Mangadu, A., Nelson, E. J., Ahmed, S. M., Qadri, F., Watt, M. H., Leung, D. T., & Khan, A. I. (2024). Potential for an Electronic Clinical Decision Support Tool to Support Appropriate Antibiotic Use for Pediatric Diarrhea Among Village Doctors in Bangladesh. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, 13(11), 605–607. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpids/piae094

Khare, S., Pathak, A., Lundborg, C. S., & Atkins, S. (n.d.). Understanding Internal and External Drivers Influencing the Prescribing Behaviour of Informal Healthcare Providers with Emphasis on Antibiotics in Rural India: A Qualitative Study. ResearchGate. 10.3390/antibiotics11040459

Kong, L. S., Islahudin, F., Muthupalaniappen, L., & Chong, W. W. (2021). Knowledge and Expectations on Antibiotic Use Among the General Public in Malaysia: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Survey. Patient Preference and Adherence, 15, 2405–2416. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S328890

Kotwani, A., Wattal, C., Katewa, S., Joshi, P. C., & Holloway, K. (2010). Factors influencing primary care physicians to prescribe antibiotics in Delhi India. Family Practice, 27(6), 684–690. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmq059

Kumah, E. (2022). The informal healthcare providers and universal health coverage in low and middle- income countries. Globalization and Health, 18(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-022-00839-z

Llor, C., & Bjerrum, L. (2014). Antimicrobial resistance: risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety, 5(6), 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042098614554919

Mahmood, S. S., Iqbal, M., Hanifi, S. M. A., Wahed, T., & Bhuiya, A. (2010). Are “Village Doctors” in Bangladesh a curse or a blessing? BMC International Health and Human Rights, 10(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-698X-10-18

Mangione-Smith, R., McGlynn, E. A., Elliott, M. N., Krogstad, P., & Brook, R. H. (1999). The Relationship Between Perceived Parental Expectations and Pediatrician Antimicrobial Prescribing Behavior. Pediatrics, 103(4), 711–718. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.103.4.711

Murray, J. L., Leung, D. T., Hanson, O. R., Ahmed, S. M., Pavia, A. T., Khan, A. I., Szymczak, J. E., Vaughn, V. M., Patel, P. K., Biswas, D., & Watt, M. H. (2024). Drivers of inappropriate use of antimicrobials in South Asia: A systematic review of qualitative literature. PLOS Global Public Health, 4(4), e0002507. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0002507

Nair, M., Tripathi, S., Mazumdar, S., Mahajan, R., Harshana, A., Pereira, A., Jimenez, C., Halder, D., & Burza, S. (2019). “Without antibiotics, I cannot treat”: A qualitative study of antibiotic use in Paschim Bardhaman district of West Bengal, India. PLOS ONE, 14(6), e0219002. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219002

Nayak, P. R., Oswal, K., Pramesh, C. S., Ranganathan, P., Caduff, C., Sullivan, R., Advani, S., Kataria, I., Kalkonde, Y., Mohan, P., Jain, Y., & Purushotham, A. (2022). Informal providers-ground realities in south asian association for regional cooperation nations: Toward better cancer primary care: a narrative review. JCO Global Oncology, 8, e2200260. https://doi.org/10.1200/GO.22.00260

NVivo 12 Pro. (n.d.). [Lumivero]. https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo

Rasu, R. S., Iqbal, M., Hanifi, S., Moula, A., Hoque, S., Rasheed, S., & Bhuiya, A. (2014). Level, pattern, and determinants of polypharmacy and inappropriate use of medications by village doctors in a rural area of Bangladesh. ClinicoEconomics and Outcomes Research: CEOR, 6, 515–521. https://doi.org/10.2147/CEOR.S67424

Salam, M. A., Al-Amin, M. Y., Salam, M. T., Pawar, J. S., Akhter, N., Rabaan, A. A., & Alqumber, M. A. A. (2023). Antimicrobial Resistance: A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. Healthcare, 11(13), 1946. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11131946

Sudhinaraset, M., Ingram, M., Lofthouse, H. K., & Montagu, D. (2013). What is the role of informal healthcare providers in developing countries? A systematic review. PloS One, 8(2), e54978. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0054978

Tandan, M. (n.d.). Antibiotic dispensing practices among informal healthcare providers in low-income and middle-income countries: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open.

Taylor, J. A., Kwan-Gett, T. S. C., & McMahon, E. M. (2003). Effectiveness of an educational intervention in modifying parental attitudes about antibiotic usage in children. Pediatrics, 111(5), e548–e554. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.111.5.e548

Trepka, M. J., Belongia, E. A., Chyou, P.-H., Davis, J. P., & Schwartz, B. (2001). The Effect of a Community Intervention Trial on Parental Knowledge and Awareness of Antibiotic Resistance and Appropriate Antibiotic Use in Children. Pediatrics, 107(1), e6. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.107.1.e6

Wang, C.-H., Hsieh, Y.-H., Powers, Z. M., & Kao, C.-Y. (2020). Defeating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria: Exploring Alternative Therapies for a Post-Antibiotic Era. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(3), 1061. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21031061

Supplementary Materials SUPPLEMENT 1

Interview guide for patient caregivers

The purpose of our interview today is to get your feedback as a caregiver of a child who is presenting to a village doctor with a primary complaint of diarrhea. We are mainly interested in understanding what you expect and desire when you take your child to see the village doctor.

As a reminder, your conversation with me today is for research purposes only. Nothing you say today will be shared with your doctor or any member of your clinical team. We hope you will feel comfortable talking openly and honestly about your experiences as a parent or caregiver. If any of my questions are not clear, please let me know and I can repeat or reword the question.

Do you have any questions before we begin?

|

Demographic information: |

|

|

Village Doctor ID (from survey) |

|

|

Caregiver ID |

CG-## |

|

Name of the interviewee |

|

|

Relationship to the child |

|

|

Age |

|

|

Sex |

|

|

Educational Qualification (highest degree) |

|

|

Occupation |

|

|

Monthly income of the family |

|

|

How many years living in this community/village |

|

|

Contact Number |

|

|

Address |

|

|

Date of Interview |

|

I. Introduction

First, I’d like to talk to you about the events leading up to coming to the village doctor for your child’s diarrhea.

1. Please tell me about yourself, and how you are related to the child.

a. What is your role in caring for the sick child?

b. Who else in your family is involved in caring for the sick child? What are their roles?

2. Please tell me briefly about your child’s illness. (Probe: How long? How often?)

a. Severity: How many stools a day? Is it bloody?

b. Any other symptoms? [dehydration level etc.]

3. Prior to coming to this village doctor, did you do anything else to try and treat your child’s

diarrhea? (Traditional healer, Homeopathy or any doctor)

a. Any medication used

i. Type of medication

ii. Where they got the medication

iii. Why did you chose this medication?

iv. Whether medication was helpful

b. Other treatment

i. Oral rehydration

ii. Home remedies

II. Reasons for choosing a village doctor

Now I’d like to talk to you about why you decided to come see this village doctor for your child’s diarrhea.

1. In your household, in what circumstances do you use village doctors?

a. For what type of ailments/diseases do you go to a village doctor?

b. What else would make you go to a village doctor instead of a clinic or hospital? (probe: severity, time of day, cost, distance)

c. Who in your household makes the decision for when you should visit a village doctor?

2. In what circumstances would you go to a clinic or hospital instead of a village doctor?

a. For what type of ailments/diseases do you go to a clinic or hospital instead of a village doctor?

b. Who in your household makes the decision to visit clinic or hospital rather than a village doctor?

3. For your child’s diarrhea today, what made you decide to visit the village doctor, instead of a clinic or hospital? [Probe: accessibility, easy communication, less fees/cost]

4. What was your reason for visiting this particular village doctor? [Probe: accessibility, cost, trust]

III Experience with village doctor

1. Please tell me about your visit to the village doctor, from the time you arrived to the time you

left.

a. How did you explain your child’s condition to the village doctor?

b. What questions did the village doctor ask you?

c. What treatments did you receive? (medication, ORS, IV fluid, etc.)

d. Did the village doctor tell you why he gave you the treatment, or how he arrived at the

decision for the treatment?

e. What other advice or guidance did the village doctor give you?

f. Were you told to come back for a follow up visit? (Probe: when)

2. At this village doctor, were you given any medication to help your child’s diarrhea?

If YES

a. Please tell me about these medications. (Probe to find out if these are antibiotics; ask to

see prescription/medication/strip or bottle if possible) Write down name of

medication/s to add to spreadsheet

b. What instructions did you receive from the village doctor? [Dose/duration]

c. What were you told about the reasons for these medications?

d. How did you feel about receiving medications?

If NO

e. What were you told about the reasons medications were not given? What advice did

you get?

f. How did you feel about not receiving medications?

3. For some families, it’s very important for them to get medications (like antibiotic pills) for

their child’s diarrhea. How important is it for you to get antibiotic pills when your child has

diarrhea?

a. Why do you say that this is important / not important?

b. What do you think that antibiotic pills do for your child?

c. How would you feel if you didn’t receive antibiotic pills from the village doctor?

d. What suggestion do you get if the doctor does not give you antibiotic pills?

4. Did the village doctor advise you to go to a clinic or hospital for the treatment of your child?

If YES

a. Why did they advise you to go to a clinic or hospital?

b. Where did they advise you to go?

c. Do you expect that you will go to the clinic or hospital? Why or why not?

5. If you don’t mind telling me, I’d like to know how much your visit to the village doctor cost.

a. Detailed cost by items: consultation, medication, other treatments, other costs

Write down details of costs to add to spreadsheet

b. Do you think these costs are reasonable? (Why / why not)

c. If a village doctor comes to visit your home then do you have to pay extra fees?

d. How does the cost of seeing a village doctor compare to going to a clinic or hospital?

e. Are you satisfied with the services you got today? Why or why not, please explain.

IV Areas for improvement

Thank you for all of your comments. To conclude, I’d like to hear your ideas about how the services from a village doctor could be improved.

1. What would you like to be different when you visit a village doctor?

2. Is there anything that a village doctor could do to make you feel more confident in the

treatment you receive?

I have reached this end of my questions. Do you have anything to add on this topic of village doctors?

SUPPLEMENT 2

The purpose of our interview today is to understand how village doctors provide care in this community, and in particular how they manage complaints of pediatric diarrhea.

As covered in the consent form, our conversation today will be used for research purposes only. When we present the results, we will aggregate everything we hear so that no individual is identified. We hope you will feel comfortable talking openly and honestly about your experiences as a village doctor. If any of my questions are not clear, please let me know and I can repeat or reword the question.

Do you have any questions before we begin?

|

Demographic information: |

|

|

Study ID (ID from Survey) |

|

|

Name of the interviewee |

|

|

Age |

|

|

Sex |

|

|

Educational Qualification |

|

|

Contact Number |

|

|

Date of Interview |

|

I. Experience becoming a village doctor

Let’s start by talking about your work as a village doctor in this community.

1. First can you tell me what made you become a village doctor?

a. What previous work had you done prior to becoming a village doctor?

2. What type of formal training did you receive to become a village doctor? (course, certificate)

a. Who provided this training?

3. What type of informal training did you receive to become a village doctor? (apprenticeship,

self-taught)

a. Who provided this training?

4. Since becoming a village doctor, what types of training have you participated in? (on-going

training to keep up skills)

a. Who provided this training?

5. Do you belong to any associations? How do they support you?

II. Role and work of a village doctor

1. As a village doctor, what do you see as the role of village doctors in meeting the health needs

of this community?

a. What type of ailments do you treat?

b. What populations do you serve?

c. How do village doctors relate to the formal healthcare system?

2. What specific services do you provide as a village doctor?

a. Diagnostics

b. Medicines (what type; specify antibiotics)

c. IVs or other treatment

d. Referrals to the formal healthcare system

e. Other referrals outside of the formal healthcare system

f. Suggestions/advice

3. What does a typical day look like for you?

a. Number of patients seen (adults, children)

b. Types of ailments/concerns

c. How does this differ by season?

d. Do you make a home visit?

4. If you feel comfortable telling me, I would like to know how you make your money as a

village doctor?

a. Role of consultation fees

b. Role of selling medications

c. Do you make enough money to meet your family’s needs?

III Practice in treatment of pediatric diarrhea

Now I’d like to ask you about how you treat children who come in with a case of diarrhea.

1. How often do you treat children who have a primary complaint of diarrhea?

a. In the last week, how many children under 5 years old with diarrhea did you see?

b. How is this different from other times of year? (variation by month/seasons/natural

calamity/outbreak)

Let’s imagine that a parent brought a child under the age of 5 to you who has been having severe diarrhea for two days.

2. What questions would you ask about the child?

3. How would you treat / help this child?

a. Medication

b. Rehydration (ORS or IV)

c. Nutritional recommendations (Food, breastfeeding suggestions)

d. Vitamins or supplements

e. Other

4. What type of medication would you consider for a child with diarrhea?

a. Types of antibiotics

i. How do you choose the best fit?

b. Other medications

i. How do you choose the best fit?

5. What information do you use to decide whether or not to give antibiotics to a child with

diarrhea?

a. What patient characteristics do you consider? (e.g., age)

b. How does your patient’s clinical presentation (e.g., severity of diarrhea, nutritional

status, can’t breastfeed) play a role in your decision to give antibiotics?

c. How does your patient’s economic situation (e.g., ability to pay) play a role in your

decision to give antibiotics?

d. Do you consider season/weather when choosing to give antibiotics?

e. Do you consider information about outbreaks / illness in other recent patients?

f. What other factors do you consider?

6. Do you use any guidelines/books/websites that help you to decide which antibiotic to use? Can you please show me that guideline/book/website if possible?

7. If you give antibiotics to a child with diarrhea, do you ask families to come for follow-up?

8. Do you ever consult someone else if you have a severe case of diarrhea?

a. If yes, who do you consult?

9. In what cases do you recommend that the family take the patient to a clinic or hospital?

10. Do you have anything you want to add about how you would treat a child with diarrhea?

IV Caregiver expectations

Now I’d like to ask about your conversations with the parents or caregivers of your patients, and how this informs your treatment.

1. When a family brings a child with diarrhea to see you, what do you think they are expecting?

a. How important is it for them to be given a medicine/antibiotic?

i. Does this differ by characteristics of the family? (e.g., wealth, education,

rural/urban)

b. Do they directly ask you to prescribe antibiotics?

2. If you saw a child and decide to not give or recommend an antibiotic, how would a family

react?

a. Do families’ expectations somehow influence what you intend to do?

3. Why do you think a family would bring a child with diarrhea to see a village doctor, instead of

going to a clinic or hospital?

V Attitudes to antibiotics

Now I’m going to ask you some questions about antibiotics in general.

1. In your opinion, what do antibiotics do for a person who is sick?

2. In what situations do you think antibiotics are most important to give to patients?

a. Types of illness

b. Severity of illness

c. Types of patients

3. In what situations, if any, do you think antibiotics may be bad for a patient?

a. Types of illness

b. Severity of illness

c. Types of patients

4. When you give antibiotics to a patient, what do you explain to them about how to use the

medication?

a. What do you tell patients about how long they should take the antibiotics?

5. Please tell me about any training you have received on antibiotic use.

a. Have you received any training on antibiotics from the health care system or the

government? (if yes, explain)

b. Have you received any training on antibiotics from drug companies? (if yes, explain)

c. Have any of these trainings taught you how to manage diarrhea in children?

d. Have any of these trainings been specific for village doctors?

6. Do you think some village doctors inappropriately prescribe antibiotics? (If yes, explain)

7. Do you think that antibiotics may be prescribed for the financial benefit of the village doctor

rather than the interest of the patients? (if yes, please explain)

I have reached the end of my questions.

Do you have anything to add on this topic of treating children with diarrhea or using antibiotics?

As a reminder, we will be visiting you again soon to talk about developing a tool that can help village doctors to make decisions about how to treat children with diarrhea.