Faculty Mentor: Paul Estabrooks (Health and Kinesiology, University of Utah)

Abstract

Through the Driving Out Diabetes Initiative (DODI), the University of Utah Wellness Bus (WB) visits communities in the Salt Lake Valley with significant health disparities, offering free health screenings, coaching and education. In addition, the WB refers visitors to other health and social services, helping them access basic resources for a continued health follow-up. In the past year, the WB implemented My Own Health Report (MOHR), a screening tool designed to assess health behaviors and psychosocial outcomes during the patient intake process, prior to their appointment with a community health worker (CHW). MOHR was implemented to facilitate easier comparison of visitor’s health behaviors relative to public health guidelines and to track progress in behavior change over time. Additionally, the tool helps guide discussions between the visitors and the CHWs and/or registered dietitians.

Although MOHR was designed to have a positive impact on visitors and enhance the provider-visitor connection, it is unclear if adding the tool to the intake process on the WB is perceived well by bus visitors. Therefore, the primary aim of this project is to understand how individuals from Hispanic/Latino backgrounds perceive the MOHR tool, particularly regarding its questions on lifestyle behaviors, lifestyle interventions, and their potential impact overall health. This study aims to provide insights into the perceptions of Hispanic/Latino individuals concerning lifestyle behavior and lifestyle interventions. Consequently, it will frame any needed changes to the MOHR tool for a continued effective attempt in reducing health disparities in the Salt Lake Valley.

The study sample (n=26) consisted of WB visitors, 18 of whom were from Hispanic/Latino backgrounds. The research participants participated in qualitative interviews to assess whether MOHR and lifestyle behaviors were perceived well. The results indicate a positive reception of the screening tool among WB visitors, with a few suggestions for further improvements to the tool. WB visitors also reported an understanding of lifestyle behaviors and how changes can improve their health; however, they expressed difficulty when implementing lifestyle changes. These findings suggest that MOHR is an effective tool for assessing lifestyle behaviors and psychosocial outcomes, yet further research is needed to enhance MOHR impact and sustain behavior change over time.

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) states that 60% of factors that promote or inhibit individual health and quality of life are related to lifestyle, yet millions of people have an unhealthy lifestyle (World Health Organization, 2009; Farhud, 2015). Specifically, lifestyle behaviors, such as physical activity, dietary intake, and sleep, have a significant influence on both physical and mental health (Farhud, 2015). Healthcare providers also recognize the importance of promoting health behavior change and how these changes can improve patient outcomes (Hamilton et al., 2019). Yet, conversations revolving around lifestyle behaviors with providers are often brief and usually initiated by patients (Hamilton et al., 2019).

Research conducted in Portugal conveyed that the study cohort believed that a healthy diet, regular physical activity, and good quality of sleep can prevent and control some diseases, while other lifestyle behaviors like smoking, excessive stress, sedentary behaviors, etc., can cause some disease; however, implementing the necessary lifestyle changes can be difficult to do (Páscoa et al., 2021). Regardless of the information revolving around lifestyle behaviors, risk factors for cardiovascular and other chronic diseases remain high in ethnic/racial minority populations in the U.S., this is especially true in Hispanic/Latino individuals (Koniak-Griffin et al., 2016). Yet, research studies have demonstrated that health programs and workshops can be used to promote health behavior change and improve education on behaviors related to nutrition and physical activity among the Hispanic/Latino communities (Mudd-Martin et al., 2013; Sanchez et al., 2021). However, access to these programs can be challenging in community settings.

Mobile Health Clinics (MHCs) are an innovative method used to deliver healthcare services to alleviate health disparities in vulnerable populations in a cost-effective way (Malone et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2017). MHCs help address some of the barriers that the public and vulnerable populations face when accessing or trying to access health care services with some of the obstacles being insurance status, transportation, financial costs, linguistic and cultural barriers, etc. (Yu et al., 2017). By reducing these barriers, MHCs can “provide more opportunities for underserved populations to screen for various conditions and learn to manage their health,” (Yu et al., 2017). Additionally, MHCs can connect their patients to broader community resources, which helps alleviate some of the social determinants of health that vulnerable communities encounter daily (Yu et al., 2017).

At the University of Utah Health, the Wellness Bus (WB), a community program under the Driving Out Diabetes Initiative (DODI), offers free health screenings, coaching, and referrals in underserved communities in the Salt Lake Valley with high health disparities (The Wellness Bus: Free Health Screenings, Coaching, and Education, 2021). The screenings that the WB offers include blood (sugar) glucose, blood pressure, cholesterol, and body mass index (BMI) (The Wellness Bus: Free Health Screenings, Coaching, and Education, 2021). Coaching and education with a registered dietician are also available to WB visitors (The Wellness Bus: Free Health Screenings, Coaching, and Education, 2021). Additionally, the WB offers referrals to visitors for other health and social services, connecting them to basic resources for continued health follow-up that address the social determinants of health. These referrals often include programs within DODI like the National Diabetes Prevention Program, Food Pharmacy, and resources with other local community organizations (Driving Out Diabetes, 2021; The Wellness Bus: Free Health Screenings, Coaching, and Education, 2021). On a larger scale, the purpose behind DODI and the WB is to “empower individuals and families to access optimal wellness,” focusing on prevention and the reduction of diabetes in Utah (Driving Out Diabetes, 2021). The roles of DODI and the WB are crucial since the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimate that 1 in 3 people in the U.S. will have diabetes by 2050, this is especially concerning in communities without access to regular health services (CDC, 2024; The Wellness Bus: Free Health Screenings, Coaching, and Education, 2021).

In the past year, the WB implemented My Own Health Report (MOHR), a screening tool that can assess health behaviors and psychosocial outcomes, during the visitor intake process before their appointment with a community health worker (CHW) (Gilbert et al., 2024; Glasgow et al., 2014; Krist et al., 2013; Krist et al., 2014). MOHR consists of questions related to frequency of lifestyle behaviors such as fruit and vegetable consumption among other questions related to mental and emotional health (Gilbert et al., 2024; Glasgow et al., 2014; Krist et al., 2014). The tool was implemented to allow for easier comparison of health and lifestyle behavior relative to public health guidelines, support bus visitor goal setting and action planning, and to track behavior change progress over time (Fisher et al., 2024; Forcier et al., 2024; Gilbert et al., 2024; Krist et al., 2013). Additionally, MOHR is designed to help facilitate appointments with CHWs and registered dietitians by providing points of conversation between the healthcare provider and the visitor (Fisher et al., 2024; Forcier et al., 2024; Gilbert et al., 2024; Glasgow et al., 2014).

While the MOHR tool was designed to have a positive impact on visitors and facilitate the connection between the provider and visitor, it is unclear if adding the tool to the intake process on the WB is perceived well by bus visitors in terms of the amount of time it takes to fill out or its personal relevance. Therefore, the primary aim of this project is to understand how people from Hispanic/Latino backgrounds perceive the MOHR tool specifically the questions about lifestyle behaviors, lifestyle interventions, and how changing these behaviors can impact overall health. In this context, health is considered as physical and mental/emotional health and any specific risk of chronic diseases like diabetes and cancer.

This study will help assess whether MOHR is an effective screening tool and whether WB visitors perceive the tool to be useful. It will also provide direction for future research on lifestyle behaviors and interventions around the Hispanic/Latino community and any needed changes to the MOHR tool for a continued effective attempt to reduce health disparities.

Methods

This study used a qualitative research design and thematic analysis to explore the experiences and receptiveness of Hispanic/Latino WB visitors towards the screening tool, MOHR. The research question guiding this study was: “How do Hispanic/Latino individuals view lifestyle behavior interventions and its impact on health?” A qualitative research design was chosen to gain a better understanding of these perceptions and the receptiveness of Hispanic/Latino individuals using the MOHR tool.

Participants

Participants (n=26) were WB visitors from various communities in the Salt Lake Valley, most (n=18) of them were from a Hispanic/Latino background. The method used to select the participants was based on convenience sampling, which is practical and contextually appropriate for a community-based study. The WB visits under-resourced communities, most with a Hispanic/Latino majority, indicating that participants recruited for the interview are likely representative of the community. The sampling method was also dependent on the participant’s availability as the interviews took place after participants wrapped up their appointments with the CHWs and/or registered dieticians. The CHWs and dieticians referred the bus visitors to a trained research assistant to explain the study and invite the visitor to participate. If visitor agreed to be interviewed, informed consent was obtained, and participants were made aware that they could withdraw from the study at any time with no penalty. Participants that were interviewed received a $10 gift card for their time as well.

Data Collection

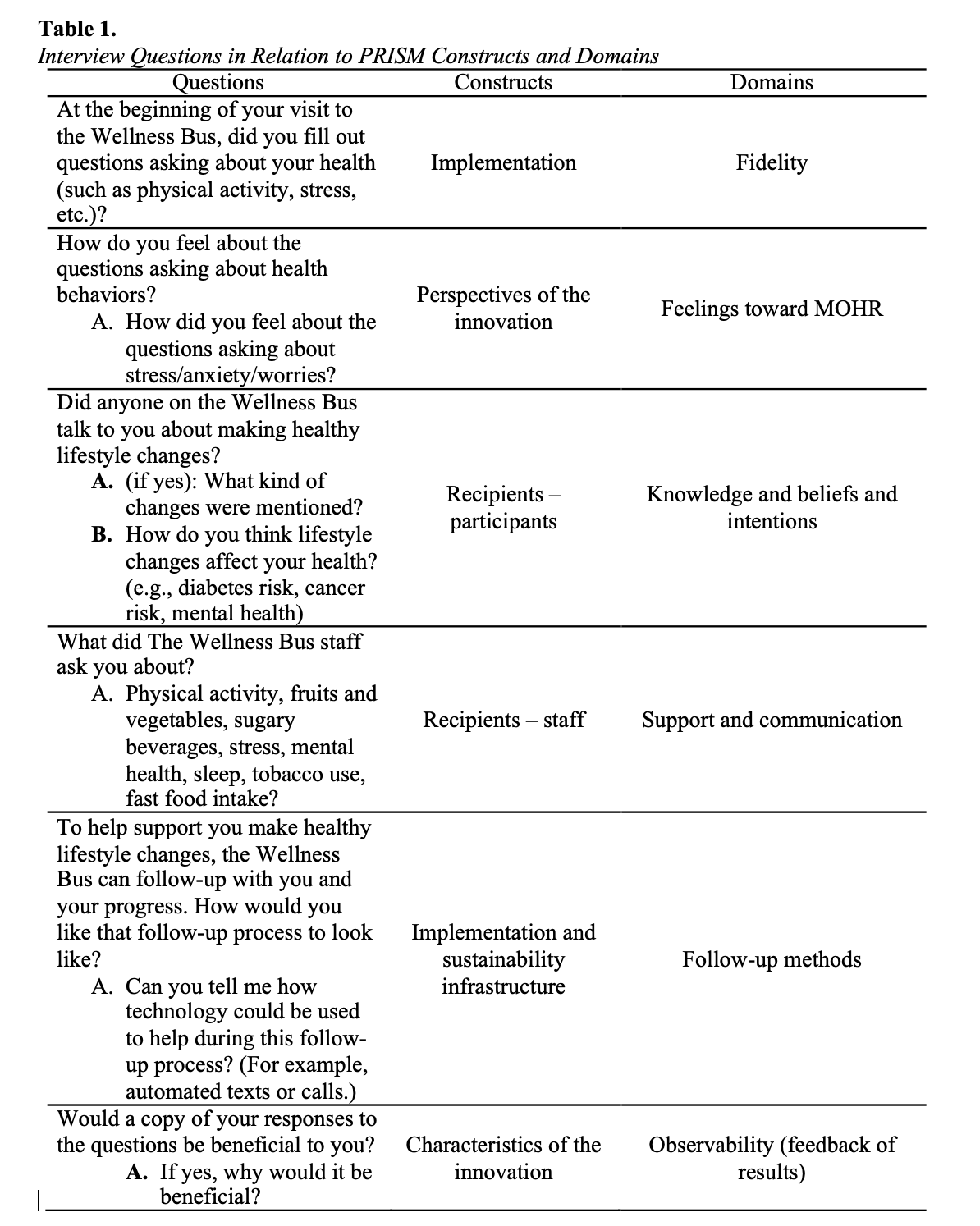

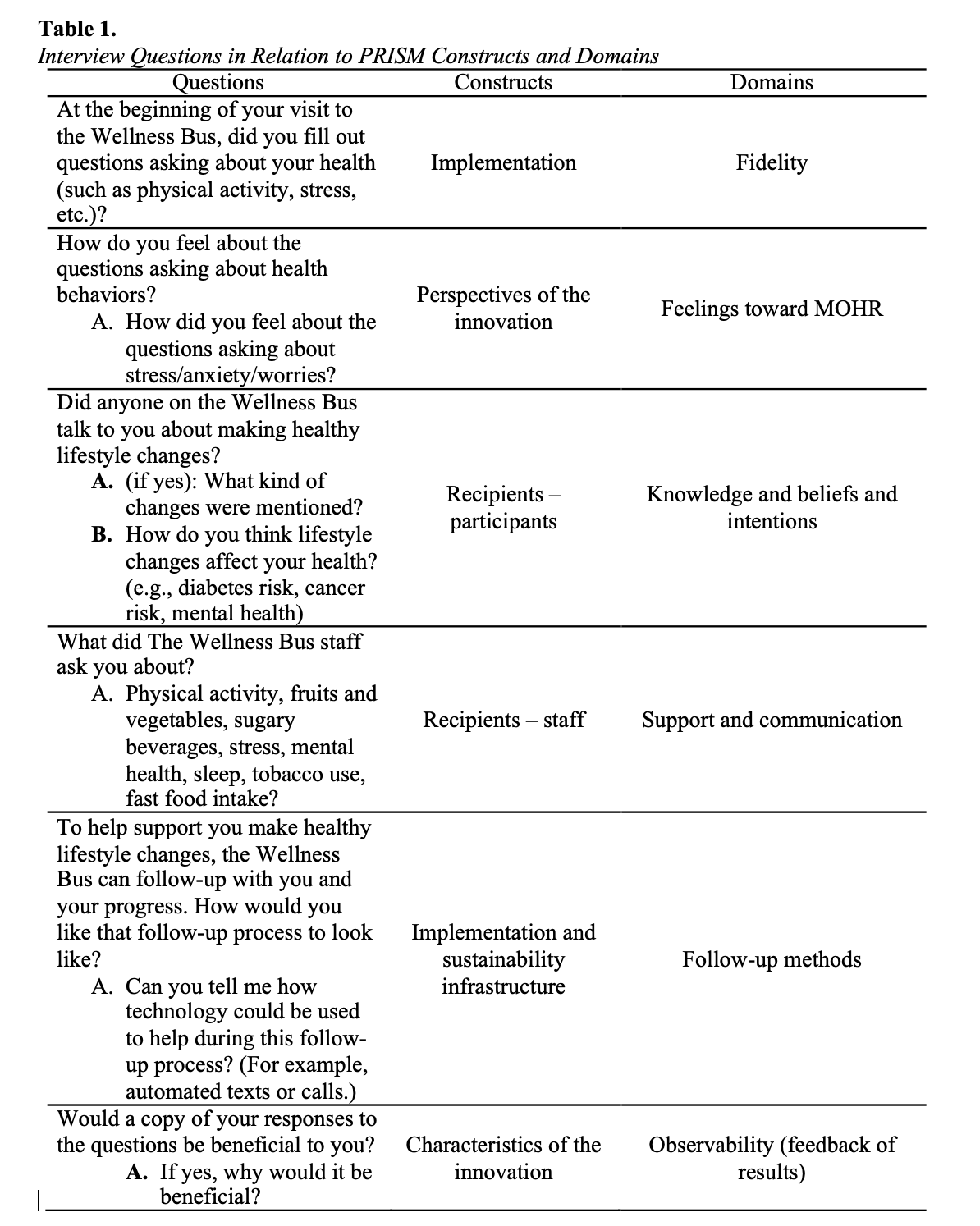

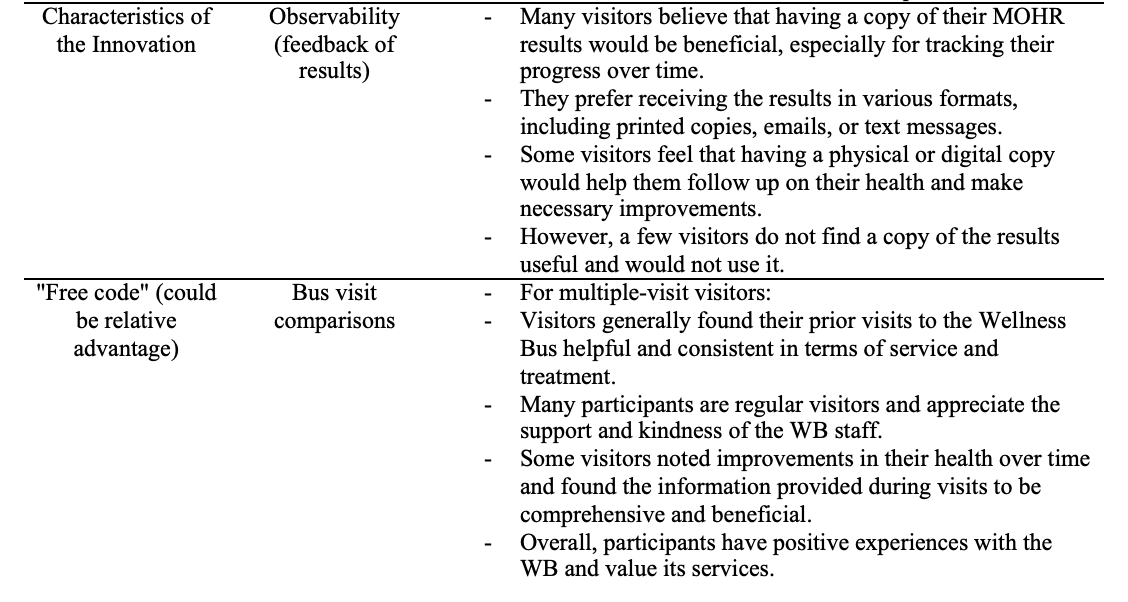

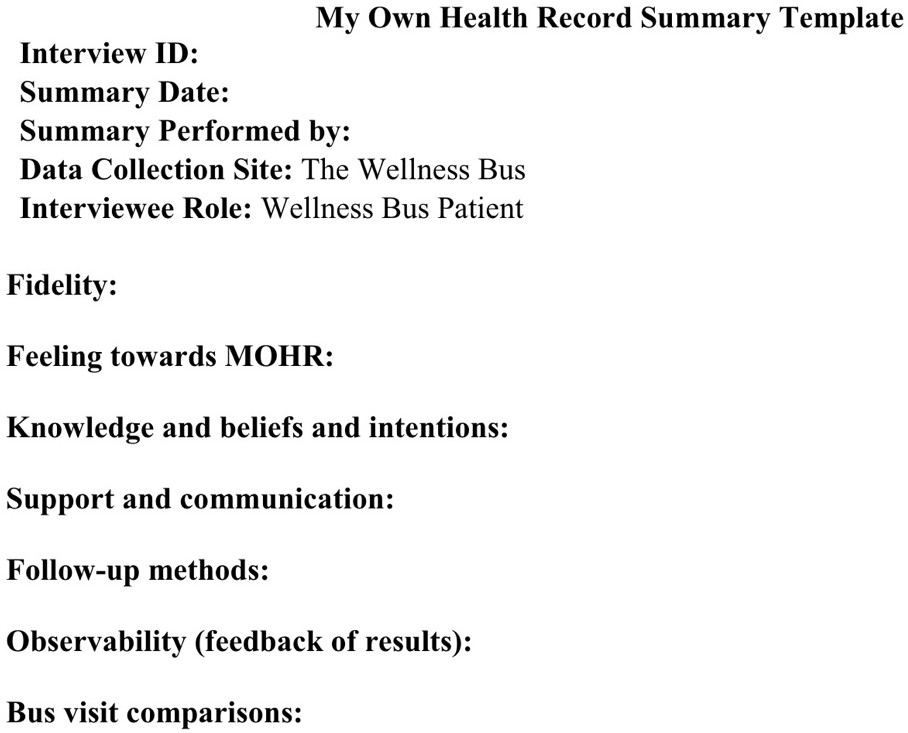

Data was collected through semi-structured interviews, each one lasting between 5-10 minutes depending on participant’s responses. Most of the interviews were conducted in Spanish (n=18) with a few in English (n=8). The interviews took place in a room within the WB which provided a quieter yet familiar setting for the participant. The interviews were audio recorded and numbered 1-26 for participant anonymity. The recordings were securely stored in a digital folder shared among the research team only and password protected electronic devices. The interview guide consisted of seven questions, with the addition of a few follow up question, and were developed using four concepts from the Practical Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM) framework (Table 1). The PRISM framework helps understand the context in which an intervention is implemented and facilitates implementation from research setting to a real-world setting. The concepts used to guide the interview questions were: (1) perspectives of the intervention, (2) characteristics of implementers, their settings, and those receiving the interventions (patients), (3) external environment, and (4) implementation and sustainability infrastructure (Aqil et al., 2009; What is PRISM? – RE-AIM, n.d.).

Data Analysis

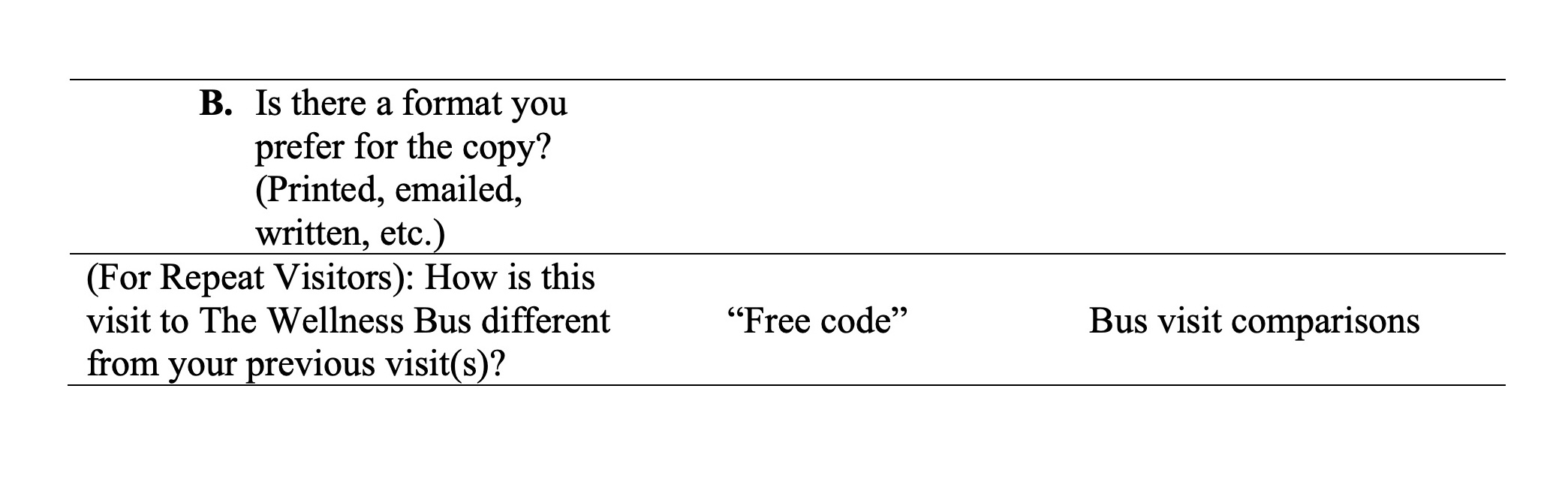

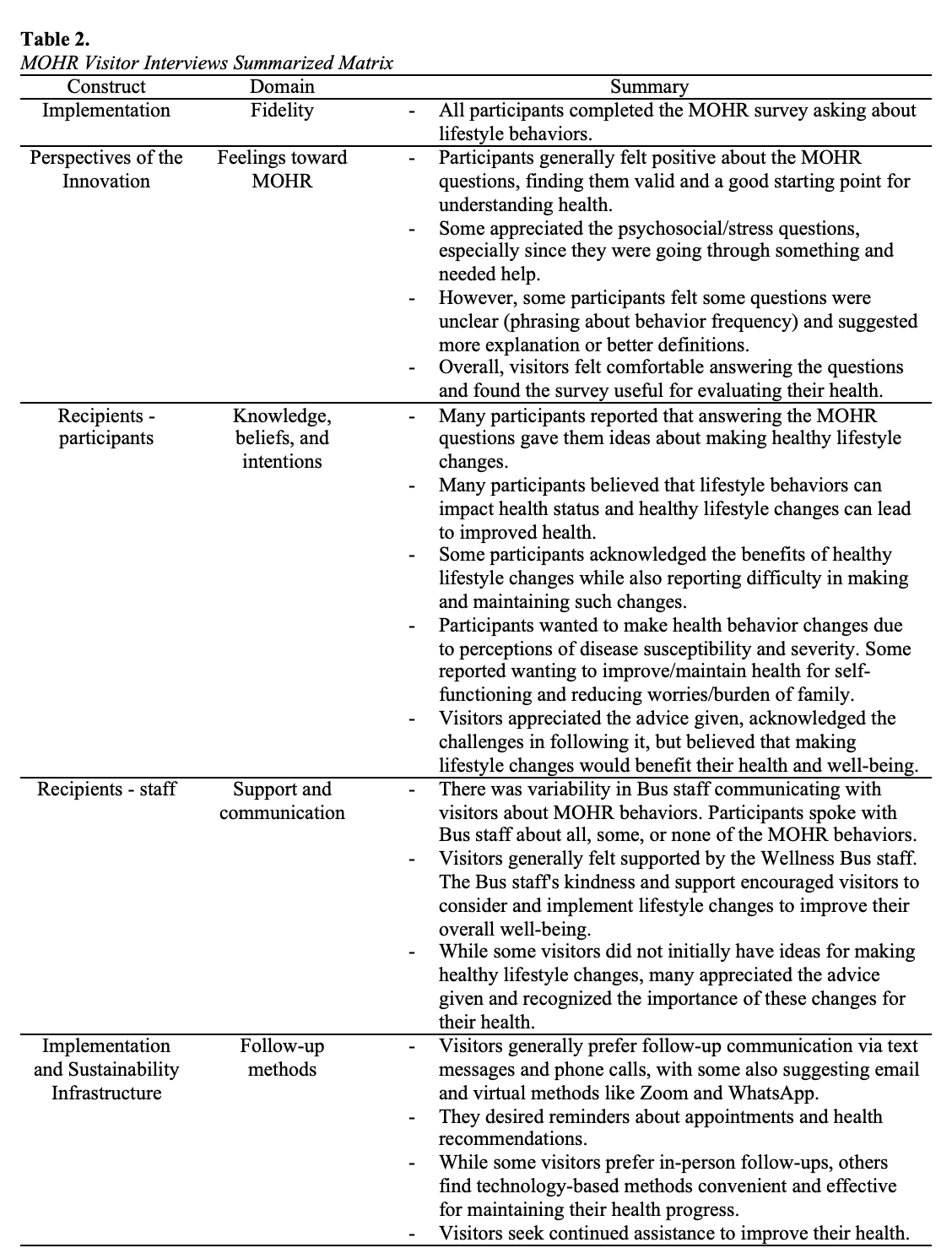

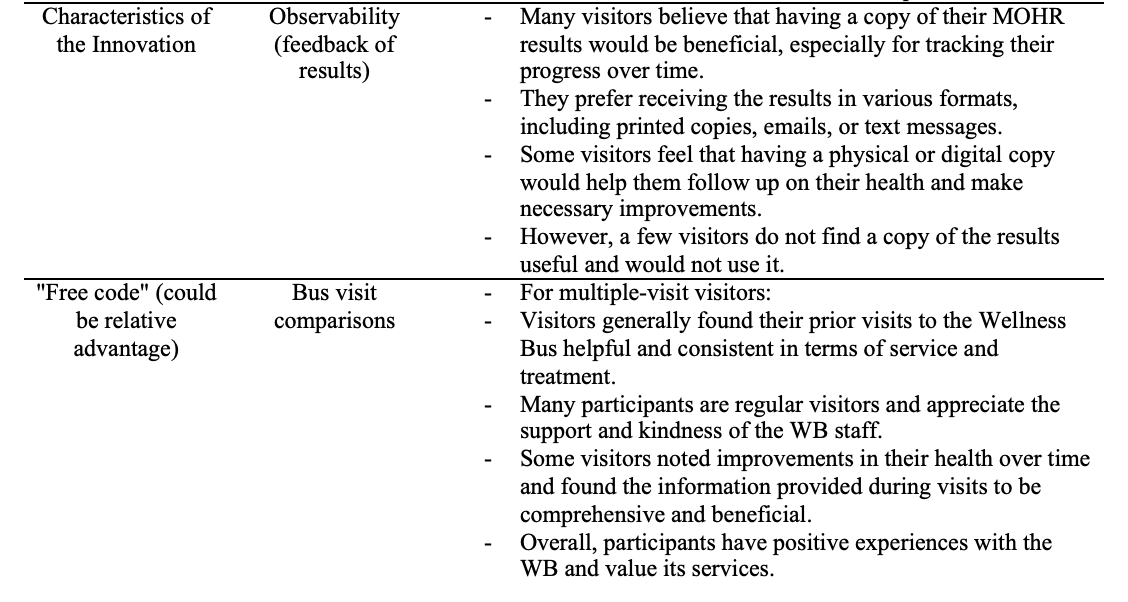

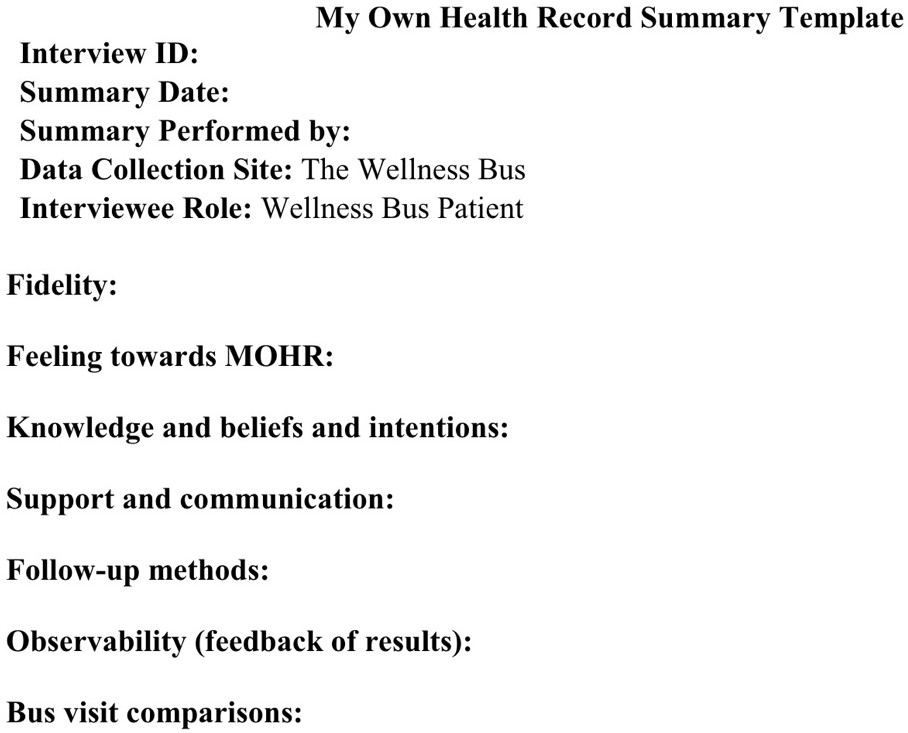

The data was analyzed using a thematic analysis. Each interview was transcribed, translated from Spanish to English if necessary, and analyzed using a rapid qualitative analysis summary template. The rapid qualitative analysis template was developed using the domains identified from the interview guide (Figure 1). A rapid qualitative analysis was used to code for themes across all interviews more efficiently than traditional thematic coding methods. The summary template was test-driven by the research team, all using the same interview, to check for consistencies, or lack of, when summarizing and to identify if adjustments to the summary template were needed. Once the summary template was finalized, each interview was summarized and rapidly condensed based on overlapping themes from the interviews.

Results

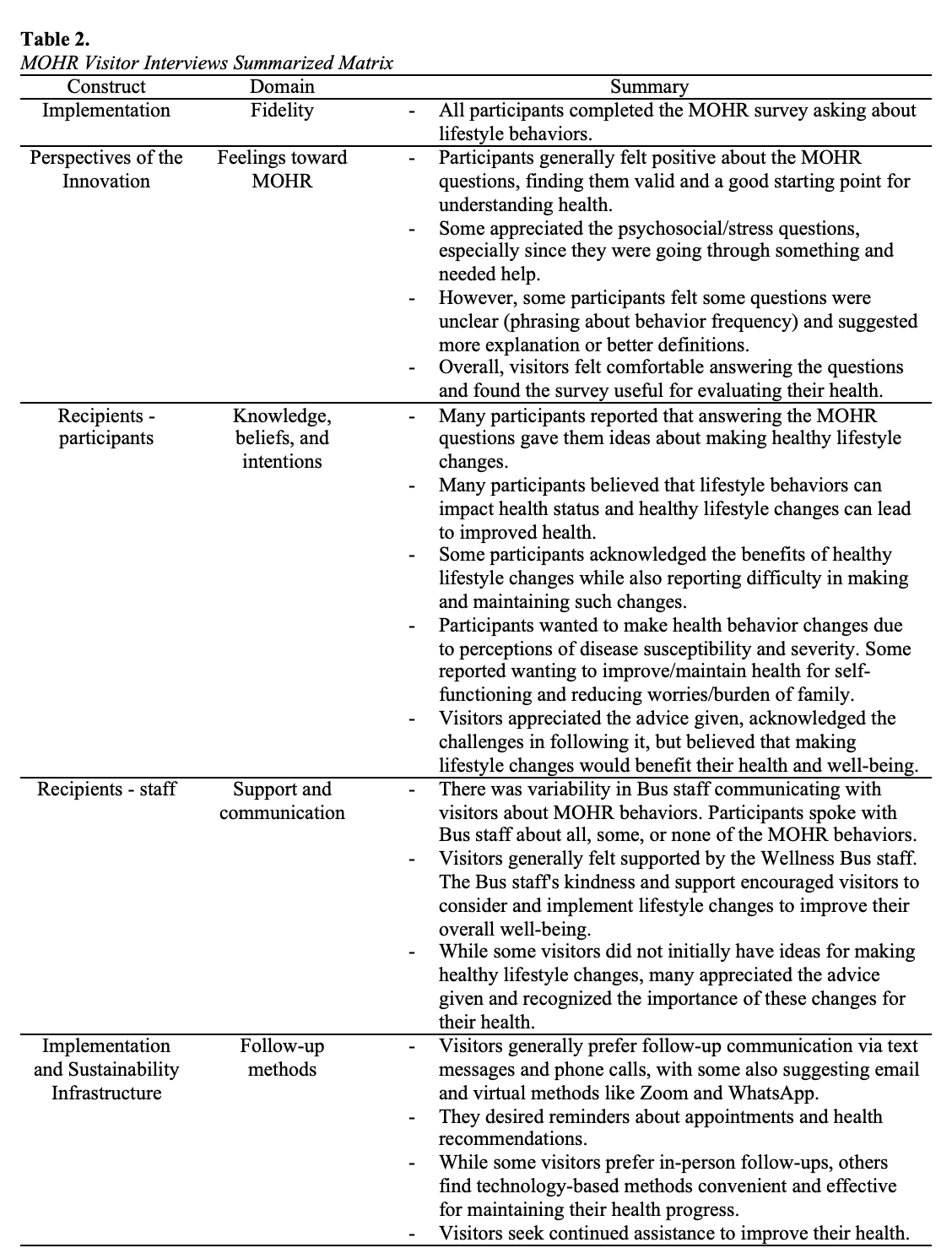

The following section presents the key themes that emerged from the interviews regarding perceptions of lifestyle behaviors and psychosocial screening among Hispanic/Latino individuals visiting the WB (Table 2). The analysis of participant responses revealed six key themes: (1) positive perceptions of the MOHR tool, (2) health behavior changes and intentions, (3) WB staff interactions, (4) follow-up preferences, (5) observability of progress, and (6) value of services.

Theme 1: Positive Perceptions of the MOHR Tool

Across all interviews participants comfortably completed the MOHR survey and found the questions on the survey useful and as a valid starting point to evaluate their health. Some participants appreciated the questions on the survey concerning mental and emotional health since these types of questions made participants reflect on their wellbeing, especially in participants that were experiencing stress, anxiety, or worry and needed help. A few participants explained that questions related to behavior frequency were a bit unclear or confusing at times and suggested changing the phrasing or better explaining the questions.

Theme 2: Health Behavior Changes and Intentions

Some participants expressed that answering MOHR questions increased their awareness and motivation to make healthy lifestyle changes. Additionally, many participants believed that lifestyle behaviors can impact their health and that healthy lifestyle changes can improve their health. Participants often expressed perceptions of disease susceptibility and severity as a reason to make lifestyle behavior changes. Other participants worried about their family and loved ones and viewed changed in health behaviors to reduce worries and/or burden on their loved ones. However, some participants recognized that making and maintaining lifestyle changes can be difficult to execute even though participants are aware of the benefits that comes with making healthy lifestyle changes for their health and wellbeing.

Theme 3: WB Staff Interactions

In general, participants had positive experiences with the WB and repeat visitors found their visits to be helpful and consistent in terms of service and treatment. The WB staff were seen as kind and supportive, playing an essential role in encouraging participants to consider and implement lifestyle changes. For participants with no initial ideas of lifestyle changes, advice was still given by the WB staff, and the participants appreciated the advice. However, there was some inconsistency with WB staff communicating with visitors about lifestyle behaviors from MOHR. Participant interviews portrayed that the staff would talk about all, some, or none of the MOHR behaviors which suggests room for more consistency when engaging with visitors about health behaviors.

Theme 4: Follow-up Preferences

Most of the participants expressed that the WB staff does a good job in their follow-up process now and stated that they would like to continue receiving follow-up in person. Nonetheless, participants communicated that the use of technology was convenient and effective for their health progress. Some participant stated that communication via text messages and phone calls as other methods of follow-ups, while others recommended the use of WhatsApp as an alternative. Participants conveyed interest in receiving appointment and health reminders through texts and calls. Some participants suggested virtual methods like Zoom for appointments, especially when scheduling conflicts arise.

Theme 5: Observability of Progress

Most participants demonstrated interest in receiving a copy of MOHR survey results, viewing it as beneficial and to keep track of their health progress over time. Some participants viewed the copy to help them individually follow-up on their health and make any necessary changes. There were many formats that participants preferred for their copy of results such as the copies being printed, emailed, or texted. On the other hand, there were a few participants that stated a copy of their results would not be useful and they would not use it.

Theme 6: Value of Services

Participants generally appreciated the support and consistency of services provided by the WB with some participants mentioning improvement in their health. Participants also expressed appreciation for the advice and information shared by the bus staff. Therefore, participants were satisfied with their interactions with the WB and perceived advantage of engaging with the bus.

Patterns and Relationships across Themes

A common pattern emerged where participants valued the support and kindness of the WB staff, which in turn encouraged participants to consider and implement lifestyle changes. So, the emotional and social support provided by the staff seems to play a critical role in motivating participants to overcome challenges when it comes to adopting healthier behaviors, something that was mentioned by participants as difficult doing so. This suggests a potential connection between support and behavior change which in turn could lead to improved health. Additionally, repeat visits to the WB correlate with positive experiences and health improvements over time which demonstrates a strong relationship with consistency of services and visitor satisfaction and in the long-term improvement to participant’s health.

Another pattern was the preference for follow-ups using text messages, calls or virtual methods which illustrates a pattern of convenience and adaptability for individual needs. Yet, the desire for in-person interaction for follow-ups among some participants further demonstrates that the relationship between personal connections and the perceived effectiveness of follow-ups. This also portrays the WB staff as essential for participants to continue investing in their health. These patterns highlight the importance of communication, consistent support, and accessible follow-up methods in cultivating positive health outcomes.

Discussion

This study aimed to assess whether the screening tool, MOHR, was perceived well by WB visitors. The study also aimed to understand perceptions of lifestyle behaviors, lifestyle interventions, and how applying these interventions can impact health. The findings revealed six key themes: (1) positive perceptions of the MOHR tool, (2) health behavior changes and intentions, (3) WB staff interactions, (4) follow-up preferences, (5) observability of progress, and (6) value of services.

Theme 1: Positive Perceptions of the MOHR Tool

This theme emerged as crucial as it demonstrates that visitors had overall positive experiences with the screening tool, implying that the tool is perceived well among its intended audience. Visitors identifying the tool as applicable and a good starting point for health evaluation further demonstrates that visitors had no negative feelings towards the tool. However, since a few visitors stated that questions related to behavior frequency were hard to understand, a change in the survey is required to make the tool more effective in tracking lifestyle behavior over time. Prior work validating the MOHR tool highlighted its strength in supporting rapid, meaningful assessment across multiple behavioral domains while being integrated standard care workflows (Krist et al., 2013; Glasgow et al., 2014). However, consistent with this study’s findings, implementation studies have shown that patient-facing tools like MOHR must continuously evolve to meet the needs of diverse literacy levels and cultural contexts (Forcier et al., 2014).

Theme 2: Health Behavior Changes and Intentions

By answering MOHR, visitors reported an increase in awareness and motivation to make healthy lifestyle changes and how these changes can have a positive impact on their health. This aligns with existing literature by Hamilton et al. (2019) and Páscoa et al. (2021), which express that changes in lifestyle behaviors can improve health outcomes. At the same time, participants stated that making these changes can be hard to execute, further aligning with Páscoa et al. (2021) in how patients in Portugal expressed difficulty when implementing lifestyle changes.

This intention-behavior gap is echoed in work showing that screening alone is insufficient to spark change unless coupled with consistent feedback and support (Krist et al., 2014). Studies also emphasize the importance of family-centered motivation, particularly in Hispanic communities, where collective well-being often drives health decision-making (Gilbert et al., 2024). This also aligns with the finding that WB visitors considered the worries and/or burdens their family and loved ones would encounter if the visitor became ill and viewed these lifestyle changes to reduce family concerns and burdens.

Theme 3: WB Staff Interactions

Participants viewed the WB staff as kind and supportive, encouraging participants to consider and implement lifestyle changes. WB staff gave visitors advice, which was appreciated by the visitors, yet there are a few inconsistencies in communication concerning lifestyle behaviors from MOHR. While it’s unclear why the differences are present, it could be due to timing since there are times when the WB is overflowing with visitors. This is also demonstrated in Hamilton et al. (2019) in which healthcare providers express timing as a barrier in conversing with patients about lifestyle behaviors. Consistency in staff using of tools like MOHR is an ongoing challenge in implementation efforts. Fisher et al. (2024) suggest that structured staff training and role integration significantly improve fidelity in delivering behavior change conversations, particularly when reinforced through tools like patient self-report surveys.

Theme 4: Follow-up Preferences

Visitors expressed that the current follow-up process on the WB is good; however, a few expressed interests in virtual methods like Zoom due to scheduling difficulties. It demonstrates a potential barrier, the hours of operation of the WB, that could be addressed by integrating other methods of access to the WB, as identified by Yu et al. (2017). Participants also showed interest in receiving appointment reminders and health resources through texts, calls, and apps like WhatsApp, demonstrating a need for constant education and access to resources, aligning with literature from Yu et al. (2017). Similar digital preferences were noted in mobile-assisted screening and brief intervention studies, where text-based and app-delivered feedback (e.g., via WhatsApp) significantly increased the feasibility and acceptability of behavior change intervention in low-resource and time-constrained settings (Forcier et al., 2024).

Theme 5: Observability of Progress

While most participants expressed interest in receiving a copy of their MOHR results, very few said they would not find a copy helpful, which was a bit unexpected. Other than that, this theme helped gauge what visitors view as useful or not and the type of formats that would be most appreciated when given a copy of the results. This aligns with findings from other studies using the MOHR tool. Specifically, personalized, visual feedback can enhance patient engagement, particularly when it supports goal setting and tracking over time (Krist et al., 2013; Glasgow et al., 2014).

Theme 6: Value of Services

Participants portrayed appreciation for the consistency of services, advice, and information, with noticeable improvements in their health. The visitors expressed satisfaction and an advantage in their engagement with the bus. This correlates with existing literature from Mudd-Martin et al. (2013) and Sanchez et al. (2021) who found that health programs can improve health outcomes. The value participants placed on the WB aligns with broader literature demonstrating that mobile health units can reduce healthcare access barriers, especially among underserved populations (Malone et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2017). Participant’s appreciation for the consistent, respectful, and culturally relevant services echoes findings that mobile health unites not only offer key services but also build trust and familiarity over time. While this study focused on a specific screening tool (MOHR), its integration within a mobile health unit may increase use and follow-up for visitors. In contrast, other studies (e.g., Fisher et al., 2024; Forcier et al., 2014) highlight how mobile-assisted digital tools (e.g., apps) can support behavior change across diverse health settings—including hospitals and outpatient clinics—but also highlight the benefit of valued services delivered by people are likely important for tool adoption and sustained use.

Implications

These findings suggest that MOHR is a practical and effective screening tool that is perceived well by WB visitors. While MOHR may benefit from some minor revisions to improve clarity and understanding, the visitors still view it as a good starting point for understanding their health. Visitors did not express any discomfort or negative emotion about filling out MOHR which was an initial concern by WB staff. The findings also demonstrate that WB visitors view lifestyle behaviors as impactful and that healthy changes can improve their health outcomes. Nonetheless, it is troublesome to implement such changes, yet the WB staff is perceived as supportive of these endeavors. This implies that with support from the staff, visitors may feel motivated to overcome challenges and adopt healthier behaviors.

Limitations

One limitation of this study is that the sample was drawn from a single mobile unit using the MOHR tool, which limits the generalizability of our findings. Still, when compared to other studies focused on lower-income or underserved audiences, many of the same themes have been identified (Gilbert et al., 2024; Sanchez et al., 2021; Mudd-Martin et al., 2013). Additionally, while interviews were relatively brief and convenience sampling was used, both approaches were pragmatic and well-suited to the mobile clinical context. Participants provided consistent, actionable feedback, supporting the credibility and utility of the insights gathered.

Conclusion

This study successfully achieved its purpose to explore perceptions of the MOHR screening tool among Hispanic/Latino participants engaged through the WB. Findings demonstrated that MOHR is not only feasible and acceptable in a mobile health unit setting but also has potential to spark meaningful discussion of lifestyle behavior change when paired staff from and of the community. The WB served as a novel and impactful delivery context for MOHR, expanding its reach beyond traditional clinical environments and into communities with limited access to care. The integration of psychosocial and behavioral screening within mobile, bilingual, and community-trusted platforms represents a promising direction for future efforts to address health disparities. Building on these results, future research should test strategies that strengthen the follow-up process—including both digital (e.g., text reminders, app-based feedback) and human delivered (e.g., health coaching, community health worker engagement) lifestyle interventions—to enhance the implementation impact of MOHR and support sustained behavior change over time. Finally, by expanding our understanding of the visitors, we can better support individuals at the WB and further address the health disparities these populations face.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere thanks to the staff at the WB for their support and guidance throughout this research study. Without their contributions, this project would not have been possible. Their knowledge and involvement were invaluable. I would also like to extend my gratitude to Candace Wilund and Mia Krause for their contribution to this project.

Appendix

Figure 1.

Rapid Qualitative Analysis Summary Template

Bibliography

Aqil, A., Lippeveld, T., & Hozumi, D. (2009). PRISM framework: A paradigm shift for designing, strengthening and evaluating routine health information systems. Health Policy and Planning, 24(3), 217–228. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czp010

CDC. (2024, September 16). About prediabetes and type 2 diabetes. National Diabetes Prevention Program. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes-prevention/about-prediabetes-type2/index.html

Driving out diabetes | University of Utah Health. (2021, April 6). https://healthcare.utah.edu/integrative-health/driving-out-diabetes

Farhud, D. D. (2015). Impact of Lifestyle on Health. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 44(11), 1442–1444.

Fisher, B., Dennison, E., McDonald, H., Rimmer, T., & Fallowfield, J. L. (2025). Can healthcare practitioners deliver health behaviour change to patients with musculoskeletal injuries as part of routine care?: A feasibility study. Physiotherapy, 127, 101461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2024.101461

Forcier, C., Constant, A., Grisard, F., Clair, E., Val-Laillet, D., Thibault, R., & Moirand, R. (2024). Feasibility and acceptability of a mobile-assisted screening and brief intervention for multiple health behaviors in medical settings. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health, 15, 21501319241303604. https://doi.org/10.1177/21501319241303604

Gilbert, J. L., Brooks, E. M., Funk, A., Webel, B., Britz, J., Kelly, C., Wilson, J., Lee, J. H., Sabo, R. T., Huebschmann, A., Glasglow, R. E., & Krist, A. H. (2024). Patient preferences for addressing unhealthy behaviors, mental health challenges, and social needs in primary care. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health, 15, 21501319241307741. https://doi.org/10.1177/21501319241307741

Glasgow, R. E., Kessler, R. S., Ory, M. G., Roby, D., Gorin, S. S., & Krist, A. (2014). Conducting rapid, relevant research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 47(2), 212–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.03.007

Hamilton, K., Henderson, J., Burton, E., & Hagger, M. S. (2019). Discussing lifestyle behaviors: Perspectives and experiences of general practitioners. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 7(1), 290–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2019.1648216

Koniak-Griffin, D., Brecht, M.-L., Takayanagi, S., Villegas, J., Melendrez, M., & Balcázar, H. (2015). A community health worker-led lifestyle behavior intervention for Latina (Hispanic) women: Feasibility and outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52(1), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.09.005

Krist, A. H., Glenn, B. A., Glasgow, R. E., Balasubramanian, B. A., Chambers, D. A., Fernandez, M. E., Heurtin-Roberts, S., Kessler, R., Ory, M. G., Phillips, S. M., Ritzwoller, D. P., Roby, D. H., Rodriguez, H. P., Sabo, R. T., Sheinfeld Gorin, S. N., Stange, K. C., & The MOHR Study Group. (2013). Designing a valid randomized pragmatic primary care implementation trial: The my own health report (Mohr) project. Implementation Science, 8(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-73

Krist, A. H., Phillips, S. M., Sabo, R. T., Balasubramanian, B. A., Heurtin-Roberts, S., Ory, M. G., Johnson, S. B., Sheinfeld-Gorin, S. N., Estabrooks, P. A., Ritzwoller, D. P., Glasgow, R. E., & For the MOHR Study Group. (2014). Adoption, reach, implementation, and maintenance of a behavioral and mental health assessment in primary care. The Annals of Family Medicine, 12(6), 525–533. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1710

Malone, N. C., Williams, M. M., Smith Fawzi, M. C., Bennet, J., Hill, C., Katz, J. N., & Oriol, N. E. (2020). Mobile health clinics in the United States. International Journal for Equity in Health, 19(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-1135-7

Mudd-Martin, G., Martinez, M. C., Rayens, M. K., Gokun, Y., & Meininger, J. C. (2013). Sociocultural tailoring of a healthy lifestyle intervention to reduce cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes risk among Latinos. Preventing Chronic Disease, 10, 130137. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd10.130137

Páscoa, R., Teixeira, A., Gregório, M., Carvalho, R., & Martins, C. (2021). Patients’ perspectives about lifestyle behaviors and health in the context of family medicine: A cross-sectional study in Portugal. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 2981. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18062981

Sanchez, J. I., Briant, K. J., Wu-Georges, S., Gonzalez, V., Galvan, A., Cole, S., & Thompson, B. (2021). Eat healthy, be active community workshops implemented with rural Hispanic women. BMC Women’s Health, 21(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-01157-5

The wellness bus: Health screenings, coaching, & education | University of Utah health University of Utah health. (2021, April 6). https://healthcare.utah.edu/integrativehealth/driving-out-diabetes/mobile-health-program

The who cross‐national study of health behavior in school‐aged children from 35 countries: Findings from 2001–2002. (2004). Journal of School Health, 74(6), 204–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb07933.x

What is prism? – Re-aim. (n.d.). Retrieved April 21, 2025, from https://re-aim.org/learn/prism/

Yu, S. W. Y., Hill, C., Ricks, M. L., Bennet, J., & Oriol, N. E. (2017). The scope and impact of mobile health clinics in the United States: A literature review. International Journal for Equity in Health, 16(1), 178. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-017-0671-2

About the authors

name:

Alejandra Huerta Hernandez

name:

Paul Estabrooks

institution:

University of Utah