Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine

99 Internalized HIV Stigma Among Women Giving Birth in Tanzania: A Mixed-Methods Study

Anya Weglarz and Olivia Hanson

Faculty Mentor: Melissa Watt (Population Health Sciences, University of Utah) and Susanna R. Cohen (Obstetrics And Gynecology, University of Utah)

Abstract

Background: Women living with HIV (WLHIV) commonly experience internalized HIV stigma, which refers to how they feel about themselves as a person living with HIV. Internalized stigma interferes with HIV care seeking behavior and may be particularly heightened during the pregnancy and postpartum periods. This thesis aimed to describe internalized HIV stigma among WLHIV giving birth, identify factors associated with internalized HIV stigma, and examine qualitatively the impacts of internalized HIV stigma on the childbirth experience.

Methods: Postpartum WLHIV (n=103) were enrolled in the study between March and July 2022 at six clinics in the Kilimanjaro Region, Tanzania. Participants completed a survey within 48 hours after birth, prior to being discharged. The survey included a 13-item measure of HIV-related shame, which assessed levels of internalized HIV stigma (Range: 0-52). Univariable and multivariable regression models examined factors associated with internalized HIV stigma. Qualitative in-depth interviews were conducted with pregnant WLHIV (n=12) and postpartum WLHIV (n=12). Thematic analysis, including memo writing, coding, and synthesis, was employed to analyze the qualitative data.

Results: The survey sample had a mean age of 29.1 (SD = 5.7), and 52% were diagnosed with HIV during the current pregnancy. Nearly all participants (98%) endorsed at least one item reflecting internalized HIV stigma, with an average endorsement of 9 items (IQR = 6). The most commonly endorsed items were: “I hide my HIV status from others” (87%), “When others find out I have HIV, I expect them to reject me” (78%), and “When I tell others I have HIV, I expect them to think less of me” (75%). In the univariable model, internalized stigma was associated with two demographic characteristics: being Muslim vs. Christian (ß = 7.123; 95%CI: 1.435, 12.811), and being in the poorest/middle national wealth quintiles (ß = 5.266; 95%CI: -0.437, 10.969).

Internalized stigma was associated with two birth characteristics: having first birth vs. having had previous births (ß = 4.742; 95%CI: -0.609, 10.093), and attending less than four antenatal care appointments (ß = 5.113; 95%CI: -0.573, 10.798). Internalized stigma was associated with two HIV experiences: being diagnosed with HIV during the current pregnancy vs. diagnosis in a prior pregnancy (ß = 5.969; 95%CI: -1.196, 10.742), and reporting experiences of HIV stigma in the health system (ß = 0.582; 95%CI: 0.134, 1.030). In the final multivariable model, internalized stigma was significantly associated with being Muslim vs. Christian (ß = 6.80; 95%CI: 1.51, 12.09), attending less than four antenatal care appointments (ß = 5.30; 95%CI: 0.04, 10.55), and reporting experiences of HIV stigma in the health system (ß = 0.69; 95%CI: 0.27, 1.12).

Qualitative discussions revealed three key themes regarding the impact of internalized HIV stigma on the childbirth experience: reluctance to disclose HIV status, suboptimal adherence to care, and the influence on social support networks.

Conclusions: WLHIV giving birth in this sample experience high rates of internalized HIV stigma. This stigma was significantly associated with being Muslim, as opposed to being Christian, attending less than four ANC appointments, and reporting experiences of HIV stigma in the healthcare setting. Other factors that were correlated to higher levels of internalized stigma were socioeconomic status, parity, and timing of HIV diagnosis, all of which can impact access to and engagement in healthcare services during the intrapartum and postpartum periods. Internalized HIV stigma impacts the childbirth experience for WLHIV, making the labor and delivery setting an important site for intervention and support.

Background

Stigma refers to the discrediting or disqualification of individuals based on a specific characteristic or attribute that is considered to be socially unacceptable.1 Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) stigma refers to the irrational or negative attitudes, behaviors, and judgments towards people affected by HIV. 2 Stigma surrounding HIV can discourage individuals living with or at risk for HIV from getting tested, seeking care, and adhering to treatment.2–4 In the healthcare setting in particular, HIV stigma manifests in various forms, including structural stigma, direct discrimination from healthcare providers, as well as internalized and anticipated stigma experienced by people living with HIV. For pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV (WLHIV), stigma can significantly impact the birth experience and subsequently affect their long-term commitment to HIV care.5–9

Internalized HIV stigma is characterized by negative self-perceptions that people living with HIV may have about themselves as a result of societal stereotypes and labels.10 Internalized stigma is often associated with suboptimal adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) and poor health outcomes, both mental and physical.11 Understanding internalized stigma is crucial for developing effective strategies to address HIV stigma and reduce its impact.12 Internalized stigma during the intrapartum period can significantly influence the lived birthing experience of WLHIV and presents a unique context to explore and mitigate internalized HIV stigma.9 While prevention of mother-to- child transmission (PMTCT) programs in Africa have been successful in achieving near- universal HIV testing for pregnant women and reducing infant HIV infections, there is a notable drop-off in overall retention in HIV care during the postpartum period.5–9

There is substantial data suggesting that WLHIV in Sub-Saharan Africa often experience substandard care from labor and delivery providers.5,6 These negative experiences can potentially interact with and reinforce preexisting internalized stigma, and can have long lasting effects on their commitment to the HIV care continuum. Respectful maternity care during the intrapartum period can reduce internalized HIV stigma, foster women’s trust in the healthcare system, and improve care engagement.13,14

Currently, knowledge about internalized stigma during the intrapartum period among WLHIV in Tanzania is limited. This study aims to examine the experiences and manifestations of internalized stigma during this period through quantitative and qualitative data. Data used in this study include surveys completed by postpartum WLHIV and in-depth interviews conducted with pregnant and postpartum WLHIV across six facilities in the Kilimanjaro Region of Tanzania as part of a larger NIH funded trial.

Using a subset of these data, I describe internalized HIV stigma among WLHIV who are giving birth, identify factors associated with HIV stigma, and qualitatively examine the impact of internalized HIV stigma on childbirth, specifically within the Tanzanian and sub-Saharan African context.

Methods

Overview

This small mixed-methods study included WLHIV who were enrolled as part of the larger MAMA (Mradi wa Afya ya Mama Mzazi) Project (NIH Clinical Trials ID: NCT05271903), which aimed to examine the manifestations of HIV stigma during the intrapartum period and develop a simulation-based provider training designed to help Labor and Delivery providers better support the births of WLHIV in Moshi, Tanzania. The protocol for the MAMA study has been published elswewhere.15 The current thesis research analyzed survey data from postpartum WLHIV (n = 103) and qualitative data from in-depth interviews with pregnant WLHIV (n = 12) and postpartum WLHIV (n = 12). Surveys were completed between March and July 2022, and interviews were conducted between January and March 2022.

Role of the student researcher

My role as an undergraduate student researcher on this project focused on internalized stigma. In addition, I participated in qualitative data management and analysis. Data collection was completed in Tanzania by the team at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center. I collaborated as part of the University of Utah team, where I independently worked on the qualitative thematic analysis, including memo writing, coding, and synthesis of the interviews for the larger project. For my thesis I analyzed data from the 13-item measure of HIV-related shame, which assessed levels of internalized HIV stigma. These data were not included in other analyses completed by the larger team. From the beginning of the project, I worked closely with both the Tanzanian and Utah teams including attending weekly meetings and reviewing other papers and submissions. Importantly, the work presented in this thesis is a deeper dive into the data with a focus on internalized stigma, and my original work.

Setting

The study was conducted at six primary health care facilities located in the Kilimanjaro Region of northern Tanzania. The six clinics together provided intrapartum services for 258 WLHIV in 2019. Four of the six facilities are government hospitals, with the remaining two facilities being Designated District Hospitals, which are supported by the government but owned and operated by a faith-based organization. The study sites were spread out between rural and urban settings, with three sites in Moshi (urban) and three sites in Rombo (rural).

Participants

Survey Participants

Survey participants were recruited from the postpartum wards at the six participating study sites. When a WLHIV arrived at the postpartum ward, a member of the clinic staff would introduce the study. If the woman was interested in learning more, the staff member would contact the study coordinator about a potential participant. The study staff would then come to the facility to further explain the study and answer any questions. If the woman was interested in participating, informed consent was obtained orally. HIV status was not mentioned or discussed during the informed consent process in order to maintain confidentiality.

In-depth Interview Participants

Interview participants were WLHIV who were enrolled in the prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) clinics at one of the six study sites at the time of participant recruitment. Study staff were on-site and available to complete the informed consent process and conduct interviews. The PMTCT nurse would inform eligible women about the study; if a woman was interested, the nurse would inform study staff to come meet with the woman to tell her more about the study and obtain informed consent; those who were unable to write provided a thumbprint in the presence of a witness. This procedure was used to recruit both pregnant and postpartum WLHIV, as women attend the PMTCT clinic during pregnancy and then up to two years postpartum.

Procedures

Survey Procedures

After the informed consent process, postpartum WLHIV who had recently given birth and not yet left the postpartum ward completed a structured survey using audio computer-assisted self- interview (ACASI) technology on tablets with Questionnaire Development System (QDS) software.16 The ACASI technology enabled the participants to complete the survey by listening to the question and response options in Swahili and then self-reporting their response option on the tablet. The ACASI modality maintained confidentiality, increased survey accessibility to a variety of literacy levels, and reduced social desirability bias.17 The survey took 30-45 minutes to complete, and study staff were present to aid participants if needed. Participants were given 5,000 Tanzanian shillings (approximately $2 USD) as compensation for their participation. Additionally, study staff reviewed the patient’s medical records to collect clinical information about the birth (e.g., patient history, clinical management, complications, and birth outcomes).

In-depth Interview Procedures

We conducted interviews with pregnant (n = 12) and postpartum (n = 12) WLHIV. The interviews lasted an average of 55 minutes with a range of 37-86 minutes long and were conducted in Swahili by one of two study team members, both of whom were trained in qualitative data collection. Participants were given 5,000 Tanzanian Shillings (approximately $2 USD) for their participation in the interviews. With participants’ consent, the interviews were audio recorded. These recordings were simultaneously transcribed and translated into English. Thematic saturation of our research objective was achieved after 24 interviews were completed, consisting of 12 with pregnant WLHIV and 12 with postpartum WLHIV.

Qualitative Interview Guide

Semi-structured interview guides were developed collaboratively by the multinational team, with context expertise from the study advisory board. Each interview guide was tailored to participants’ particular circumstances (i.e., pregnant vs. postpartum). The guides included open-ended questions and probes that aimed to understand how HIV stigma is experienced by WLHIV during the intrapartum period, the impact of implicit bias by health care providers on patient care, and WLHIV’s experiences related to respectful maternity care. More specifically, interviews with pregnant WLHIV aimed to explore the participants’ expectations and desires for birth, perceptions of health care providers’ use of respectful maternity care principles, and anticipatory stigma related to birth. Additionally, interviews with postpartum WLHIV aimed to explore participants’ experiences with birth, perceptions of health care providers’ use of respectful maternity care principles, experiences of stigma during birth, and role of internalized stigma during birth. Although interviews covered topics beyond internalized HIV stigma, this study emphasized discussions of how internalized stigma impacted the pregnancy and birth experiences for WLHIV.

Measures

Internalized HIV Stigma

Internalized HIV stigma was assessed using Scale A of the HIV and Abuse Related Shame Inventory (HARSI).18 The measure includes 13 items that asked about experiences of internalized stigma (e.g., “It is hard to tell other people about my HIV infection.” “I am ashamed that I have HIV.”). Items were presented on a Likert scale (0- 4), with 0 corresponding to “not at all”, indicating no endorsement of the item, and 4 corresponding to “very much”, indicating substantial endorsement of the item and were summed for a possible range of 0–52.

Demographics and HIV Information

The structured survey included demographic questions about age, education, marital status, literacy, religion, and household wealth. Household wealth was measured in quintiles and calculated from a wealth index based on 10 questions about household assets.19 Each participant’s birth history, including parity number of antenatal care visits, was extracted from medical records. Additionally, HIV specific information was collected, including timing of HIV diagnosis, general HIV status disclosure, HIV status disclosure to partner, partner’s HIV status, and if the participant was adherent to their ARV treatment and taking it upon hospital admission.

Data Analysis

Quantitative Analysis

Participant data from the structured survey and as well as the medical record data collected by the study staff were merged and exported to Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) software v.25 for data cleaning and analysis. A descriptive analysis of participant characteristics was completed, with variables classified under sociodemographic, birth statistics, or HIV related experiences. We compared the characteristics of women with and without HIV using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables.

To identify factors associated with internalized stigma, we examined regression coefficients and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals for factors associated with internalized HIV stigma. Covariates that were significant at p<0.1 in a univariable analysis were included in the final multivariable model.

Qualitative Analysis

In depth interviews were analyzed using applied thematic analysis with an emphasis on qualitative memo writing. An iterative process of analysis allowed revisions to be made to the guides to develop a more complex and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon. Data collection in each participant group proceeded until thematic saturation had been reached, meaning that additional data points did not add significant thematic insight to the research question.

After reading the transcript multiple times, detailed memos were written for each transcript, highlighting emerging themes across the domains of analysis. Each memo was reviewed by one additional trained analyst to confirm its completeness and rigor. Memos were structured based on the principles of respectful maternity care, with specific structure lending to understanding HIV stigma (internalized, anticipated, and enacted). NVivo (Version 12) was used to thematically code each memo, and emerging themes specific to internalized HIV stigma were identified.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College Research Ethics Review Committee, the Tanzanian National Institute for Medical Research, and the University of Utah Institutional Review Board.

Permission to conduct the research was obtained from the District Medical Officers in the Moshi and Rombo districts. All eligible participants provided informed consent before their participation. Consent was obtained orally for survey participants. Signed consent forms were completed for in-depth interview participants, and those who were unable to write provided a thumbprint in the presence of a witness. Data analyses were conducted on de-identified data to maintain the confidentiality of participants.

Results

Survey Findings

Description of Sample

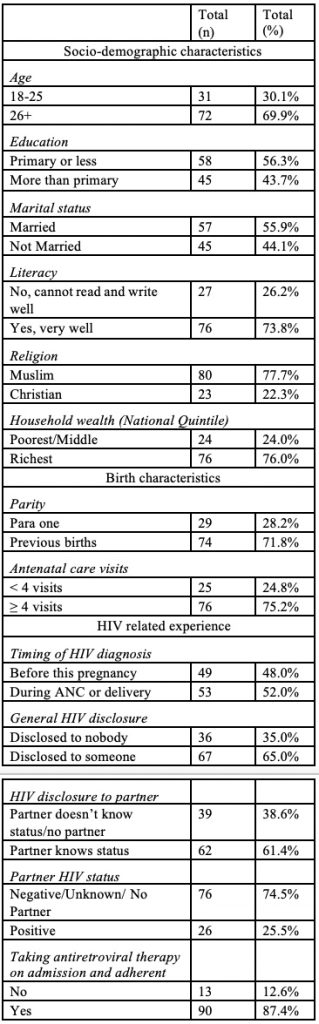

A total of 103 WLHIV completed the survey. The mean age and standard deviation (SD) of the survey participants was 29.1 ± 5.7 years. Approximately half of participants were married (55.9%, n = 57), and most were literate (73.8%, n = 76). The majority (77.7%, n = 80) identified as Muslim. Just over half of participants were aware of their HIV diagnosis prior to their pregnancy (48%, n = 49), and the other half of participants were informed of their HIV status during the index pregnancy (52%, n = 53). The majority of participants (87.4%, n=90) self-reported having taken their ARV medication since being admitted as well as being previously adherent to their ARV regiment. Adherence was defined as taking ARVs consistently over the previous four days. Table 1 summarizes the survey participants’ demographic characteristics, birth characteristics & HIV related experience.

Table 1: Participant demographics, birth characteristics & HIV related experience (n=103)

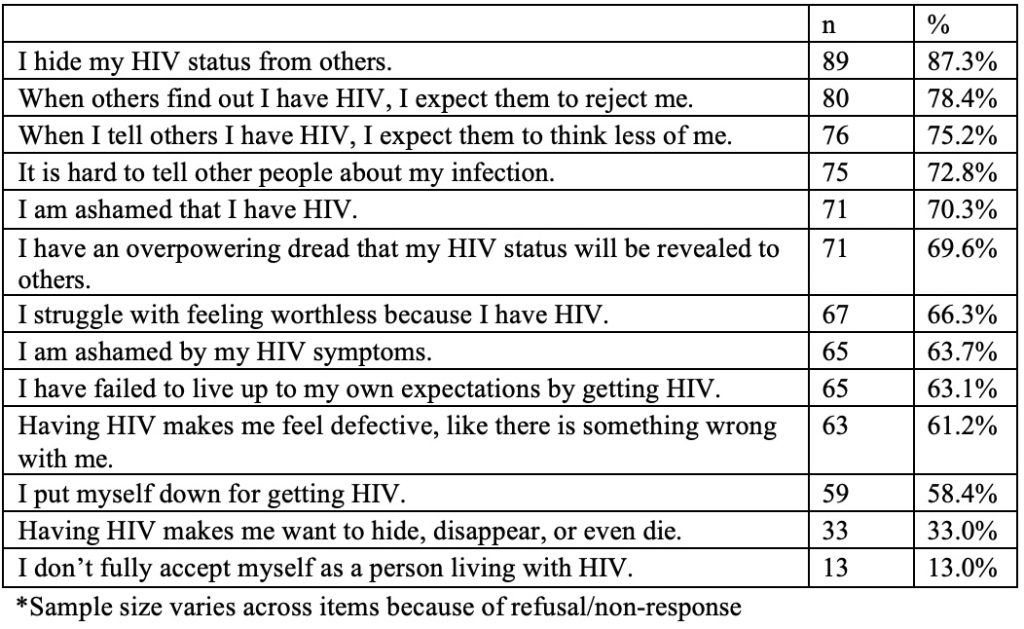

Internalized HIV Stigma

Table 2 presents how participants responded to the 13 items for measuring internalized HIV stigma. Any survey response between 1 and 4 (“a little bit” – “very much”) on the Likert scale was interpreted as endorsement of that item. Almost all (98%, n = 101) endorsed at least one internalized stigma item; on average, participants endorsed 9 (IQR=6) items. The most commonly endorsed items were: “I hide my HIV status from others” (87%), “When others find out I have HIV, I expect them to reject me” (78%), and “When I tell others I have HIV, I expect them to think less of me” (75%).

Table 2: Agreement with items on the internalized HIV stigma scale (n = 103*)

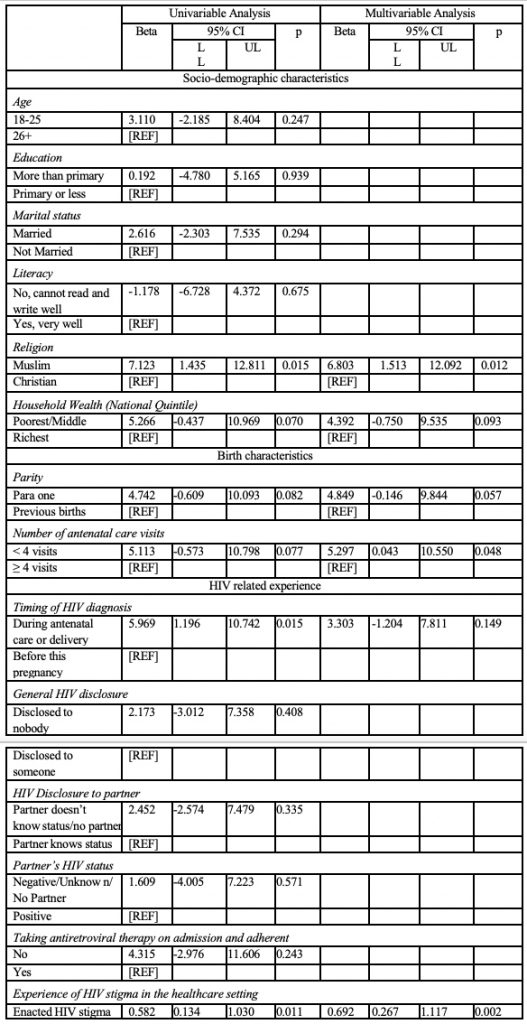

Predictors of Internalized HIV Stigma

Table 3 summarizes the estimates of the univariable and multivariable linear regression analysis of the demographic, social, and behavioral predictors of internalized HIV stigma. In the univariable model, internalized stigma was associated with two demographic characteristics: being Muslim vs. Christian (ß = 7.123; 95%CI: 1.435, 12.811), and being in the poorest/middle national wealth quintiles (ß = 5.266; 95%CI: – 0.437, 10.969). Internalized stigma was associated with two birth characteristics: having first birth vs. having had previous births (ß = 4.742; 95%CI: – 0.609, 10.093), and attending less than four antenatal care appointments (ß = 5.113; 95%CI: – 0.573, 10.798). Internalized stigma was associated with two HIV experiences: being diagnosed with HIV during the current pregnancy vs. prior (ß = 5.969; 95%CI: -1.196, 10.742), and reporting experiences of HIV stigma in the health system (ß = 0.582; 95%CI: 0.134, 1.030).

In the final multivariable model, internalized stigma was significantly associated with being Muslim vs. Christian (ß = 6.80; 95%CI: 1.51, 12.09), attending less than four antenatal care appointments (ß = 5.30; 95%CI: 0.04, 10.55), and reporting experiences of HIV stigma in the health system (ß = 0.69; 95%CI: 0.27, 1.12).

Table 3: Predictors of internalized HIV stigma

Qualitative Findings

Description of Sample

A total of 24 WLHIV participated in the interviews: 12 were pregnant and 12 were recently postpartum. The average age of interview participants was 29.5 years old. Only 45.8% (n = 11) of participants had received some secondary (i.e., high school) education. The average number of prior births was 2.08 (median 1.5), not including the most recent birth for postpartum participants. Two-thirds (66.7%; n = 16) were married, 20.8% (n = 5) were in a relationship but not married, 8.3% (n = 2) were single and not in a relationship, and 4.2% (n=1) were separated from their spouse or divorced. Most participants (70.8%, n = 17) were aware of their HIV status before their current pregnancy (pregnant participants) or most recent pregnancy (postpartum participants), and 29.2% (n = 7) received their HIV diagnosis during their current pregnancy (pregnant participants) or most recent pregnancy (postpartum participants).

Themes related to impact of internalized HIV stigma

In considering the impact of internalized HIV stigma on the birth experience, three broad themes emerged: 1) reluctance to disclose HIV status, 2) impacts on support systems, and 3) poor engagement in HIV care. The first theme, ‘reluctance to disclose HIV status’, represents the hesitancy WLHIV have towards revealing their HIV status to others, both within and outside their family. The second theme, ‘impacts on support systems’, represents the powerful role internalized stigma plays in shaping WLHIV’s relationships with others. The final theme, ‘poor engagement in HIV care’, represents how feelings of shame because of one’s HIV status contribute to reluctance to seek out HIV care across the antenatal, intrapartum, and postnatal continuum.

Reluctance to disclose HIV status

Many women acknowledged that their internalized HIV stigma resulted in their reluctance to share their HIV status with others. During discussions of HIV status disclosure, many women acknowledged that a combination of anticipated stigma and internalized stigma were the primary drivers for their lack of HIV status disclosure to others. Many women talked about how by not revealing their status to others, they were able to deny the reality of their diagnosis, compelled by feelings of shame and embarrassment. One postpartum WLHIV expressed her desire to receive a new maternal health card (a card that all pregnant mothers receive that states HIV status among other things) that did not state her HIV status. She had recently found out about her HIV status during her most recent pregnancy and had received a new card with her updated HIV status. Driven by her desire to hide her HIV status from others as well as denial herself, she wished her card still stated that she was HIV negative: I mean, I wished to change the card and get a new card that has not been filled in like this, but I thought that I would still be deceiving myself. (Postpartum WLHIV, 24 years old, learned her status during this pregnancy).

Impacts on support systems

Many women described how their feelings of shame impacted their relationships and consequently limited the amount of support they had from family or friends. Participants commonly spoke about how they did not want their HIV status to be an emotional burden to others, which led them to withhold this information. As a result, participants lacked key support getting to appointments or taking their medication.

One postpartum WLHIV described how she didn’t want her mother or other family members to know about her HIV status, because her mother has her own health issues, and she didn’t want her HIV status to cause bigger problems. In the quote below, she was confiding in her husband who was her primary support person and would get her medication for her when she was sick.

I told my husband, ’Do not worry. If you tell people like my mother, who have BP complications, to tell her about this problem will cause bigger problems.’ Therefore, we remained like that, and even when I am seriously sick, he is the one who will come to get the medicine for me. (Postpartum WLHIV, 37 years old, learned her status during this pregnancy)

Suboptimal adherence to care

Several women discussed how internalized stigma contributed to poor adherence to HIV care. Several women expressed that not taking their ARTs allowed them to ignore or reject their HIV status. Others noted that they didn’t attend the clinic or didn’t take their medication because they were afraid that others would learn of their HIV status and treat them differently.

One pregnant WLHIV explained that when she learned about her HIV status during her previous pregnancy, she had not accepted her diagnosis and so she wanted to throw the medication away. I didn’t like to swallow the medicine because I hadn’t accepted myself and I would say to myself, ‘Why should I be swallowing them? Let me throw them away.’ (Pregnant WLHIV, 22 years old, learned her status prior to this pregnancy).

Another pregnant WLHIV talked about her feelings of fear and shame when she was diagnosed with HIV during her current pregnancy. At first, she didn’t want to believe the test results and refused to start the ARTs she was told to take. She eventually came back for a second test with her mother and then felt that with her mother’s support and confirmation that she could accept the results for herself. Her experience emphasizes the impact that support and outside acceptance of one’s HIV diagnosis has on a woman’s self-stigma and acceptance of her status.

Yes. I was afraid of the results, and I ran away from them (she laughs). Isn’t it that once you receive the results you should take the medicine? That is what I was afraid of, and I thought that they were setting me up, that the results were not mine. I went and called my mother on the phone, and she came from Dar es Salaam. She accompanied me the second time and I was tested in her presence and when the results came out, I accepted them… ‘Is it true that you have seen them, my mother?’ Then I told her that if she had seen them then they must be true and then I started the medicine. But before that I had refused completely to start the medicine. (Pregnant WLHIV, 28 years old, learned her status during this pregnancy)

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to describe internalized HIV stigma among WLHIV giving birth in Tanzania, to identify factors associated with internalized HIV stigma, and to qualitatively examine the impacts of internalized HIV stigma on the childbirth experience. We found that WLHIV were more likely to endorse stigmatizing attitudes if they were Muslim, were in the poorest/middle national wealth quintiles, had attended fewer antenatal care appointments, were having their first birth, were diagnosed with HIV during the current pregnancy, and had previous experiences of stigma within the healthcare setting. Key themes identified in the interviews included: reluctance to disclose HIV status, suboptimal adherence to care, and influence on social support networks. These findings provide valuable insights into the prevalence, associated factors, and impacts of internalized HIV stigma on WLHIV giving birth.

Identifying as Muslim was significantly associated with increased stigma, which indicates certain cultural and religious influences on perceptions of HIV and stigmatizing attitudes. Our study survey did not specifically assess participants’ degree of religiosity, and this presents a potential opportunity for future studies focused on examining how religious affiliation influences attitudes towards HIV stigma. One study, done in Uganda, looked specifically at the role of religious leaders in advocating for HIV prevention strategies among young people. This study found that nearly 70% of young people, ages 15-24, adopted HIV prevention strategies recommended by religious leaders.20 While this study observed advocacy for prevention it didn’t examine attitudes towards people living with HIV. Future studies working with religious institutions and leaders, exploring religious attitudes towards HIV, would provide valuable insights to guide the development of stigma reduction interventions that specifically target religious contexts.

Attending fewer than four antenatal care appointments was also associated with higher levels of internalized stigma. Because our study was cross-sectional, we do not know if less healthcare engagement during pregnancy may contribute to increased experiences of stigma, or if stigma prevented PLWH from attending prenatal care. The latter is plausible, given prior research that suggests that stigma can significantly impact the birth experience and therefore their long-term HIV care engagement.5–9

Additionally, individuals who reported experiences of HIV stigma in the healthcare system had higher levels of internalized stigma. This mirrors prior research suggesting that WLHIV often experience substandard care from healthcare providers, which can reinforce preexisting internalized stigma and have long lasting effects on their commitment to the HIV care continuum.5,6 These findings highlight the importance of addressing sociocultural and healthcare-related factors to mitigate internalized HIV stigma among WLHIV during childbirth. Future research and policy efforts should focus on implementing interventions aimed at the labor and delivery setting which have the potential to significantly enhance the childbirth experience and improve overall well- being of WLHIV.

Socio-economic status as indicated by national quintile of household wealth was marginally associated with internalized stigma (p<.10) in the univariate model. Although there was no statistical significance in the multivariate model, socio-economic status is a critical social determinant of health, including factors such as income, education, employment, and housing. These factors impact all areas of a person’s life and can significantly influence an individual’s ability to access HIV care which can consequently impact the way they feel about themselves and their HIV status.

Narratives from in-depth interviews provided deeper insights into the impacts of internalized HIV stigma on the childbirth experience. While prevention of mother-to- child transmission (PMTCT) programs in Africa have been successful in achieving near- universal HIV testing for pregnant women and reducing infant HIV infections, there is a notable drop-off in overall retention in HIV care during the postpartum period.5–9 Across the interviews, participants expressed fear and apprehension about disclosing their HIV status, leading to isolation and a lack of social support. Many women acknowledged that their feelings about their HIV status resulted in either their reluctance to share their HIV status with others or not share their status at all. Participants also expressed feeling like a burden to others when disclosing their HIV status, which subsequently impacted their relationships. These feelings not only contributed to self-stigmatization but also restricted the support women received from family and friends. Furthermore, internalized HIV stigma negatively impacted adherence to healthcare and treatment recommendations, potentially compromising the health outcomes of both mother and baby. Previous studies also indicate that internalized stigma is often associated with suboptimal adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) and can lead to poor health outcomes, both mentally and physically.11 A variety of factors seemed to influence adherence, including fear and anticipated stigma if someone found their medication and inaccessibility of medications due to geographic or social barriers. These findings once again highlight the need for interventions that create a supportive and non- stigmatizing environment, promote disclosure support, and enhance adherence to care among WLHIV during the childbirth experience.

This study had several limitations that must be considered. First, all women who participated in interviews were recruited from PMTCT clinics where they were either receiving antennal or postpartum care. WLHIV who regularly attend PMTCT appointments may have different experiences of internalized HIV stigma as compared to WLHIV who have poor care engagement.

This is particularly likely, given that our survey results suggest that WLHIV who attended less than four ANC appointments were more likely to experience internalized HIV stigma. We were not able to recruit WLHIV for interviews who had dropped out of PMTCT care, which may have led us to missing some key insights and perspectives.

Second, because our study was cross- sectional, directionality of our findings cannot be assumed and identified associations should not be interpreted as causal relationships. Third, given the sensitive topic of HIV and women’s experiences living with HIV, survey responses and the data reported during interviews were likely affected by social desirability bias. To minimize social desirability bias, ACASI technology was utilized to administer the survey, and both survey and interview participants were told that the survey results and what they discussed in their interview would be kept confidential and not affect their care. Lastly, we collected limited socio-demographic characteristics of the WLHIV who participated in the interviews, making it likely that some characteristics were not evenly represented. This likely lack of representation could have introduced bias into the data derived from the interviews, not providing a representative range of perspectives and experiences related to internalized HIV stigma.

Conclusion

WLHIV giving birth experience high rates of internalized HIV stigma. In this setting, WLHIV who were Muslim, as opposed to being Christian, attended less than four ANC appointments, and reported experiences of HIV stigma in the healthcare setting were more likely to experience internalized HIV stigma. Internalized HIV stigma impacts the childbirth experience for WLHIV, making the labor and delivery setting an important site for intervention and support. Future studies should develop and test interventions to address and reduce internalized stigma among WLHIV, specifically targeting the intrapartum period as a vulnerable time for WLHIV.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to everyone who supported my work on this paper. I want to thank Drs. Melissa Watt and Susanna Cohen (MPIs) for their mentorship and guidance, the study teams at the University of Utah and Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center, as well as my co-research assistant, Olivia Hanson for her support through the thesis process.

I also want to thank the study participants, data collectors, supervisors, hospital administrators, and staff for their willingness to give their time and information for this study.

Funding

This thesis used data from a study funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (R21 TW012001, MPI, Watt & Cohen). My work as an undergraduate research assistant was supported by the University of Utah Office of Undergraduate Research, Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program (UROP) award.

References

1. Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Simon and Schuster; 2009.

2. Standing Up To HIV Stigma. HIV.gov. Accessed March 3, 2023. https://www.hiv.gov/hiv- basics/overview/making-a-difference/standing-up- to-stigma

3. Katz IT, Ryu AE, Onuegbu AG, et al. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(3 Suppl 2):18640. doi:10.7448/IAS.16.3.18640

4. Logie CH, Okumu M, Kibuuka Musoke D, et al. Intersecting stigma and HIV testing practices among urban refugee adolescents and youth in Kampala, Uganda: qualitative findings. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24(3):e25674. doi:10.1002/jia2.25674

5. Turan JM, Miller S, Bukusi EA, Sande J, Cohen CR. HIV/AIDS and maternity care in Kenya: how fears of stigma and discrimination affect uptake and provision of labor and delivery services. AIDS Care. 2008;20(8):938-945. doi:10.1080/09540120701767224

6. Sando D, Kendall T, Lyatuu G, et al. Disrespect and Abuse During Childbirth in Tanzania: Are Women Living With HIV More Vulnerable? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2014;67(Suppl 4):S228-S234. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000000378

7. CICHOWITZ C, WATT MH, MMBAGA BT. Childbirth experiences of women living with HIV: A neglected event in the PMTCT care continuum. AIDS Lond Engl. 2018;32(11):1537-1539. doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000001860

8. Watt MH, Cichowitz C, Kisigo G, et al. Predictors of postpartum HIV care engagement for women enrolled in prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) programs in Tanzania. AIDS Care. 2019;31(6):687-698. doi:10.1080/09540121.2018.1550248

9. Knettel BA, Cichowitz C, Ngocho JS, et al. Retention in HIV Care During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period in the Option B+ Era: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Studies in Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2018;77(5):427-438. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000001616

10. Person B, Bartholomew LK, Gyapong M, Addiss DG, van den Borne B. Health- related stigma among women with lymphatic filariasis from the Dominican Republic and Ghana. Soc Sci Med 1982. 2009;68(1):30-38. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.040

11. Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, et al. How Does Stigma Affect People Living with HIV? The Mediating Roles of Internalized and Anticipated HIV Stigma in the Effects of Perceived Community Stigma on Health and Psychosocial Outcomes. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(1):283-291. doi:10.1007/s10461-016-1451-5

12. Akatukwasa C, Getahun M, Ayadi AME, et al. Dimensions of HIV-related stigma in rural communities in Kenya and Uganda at the start of a large HIV ‘test and treat’ trial. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(5):e0249462. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0249462

13. Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA. Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev MCRR. 2013;70(4):351-

379. doi:10.1177/1077558712465774

14. Rubashkin N, Warnock R, Diamond-Smith N. A systematic review of person- centered care interventions to improve quality of facility-based delivery. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):169. doi:10.1186/s12978-018-0588-2

15. Watt MH, Cohen SR, Minja LM, et al. A simulation and experiential learning intervention for labor and delivery providers to address HIV stigma during childbirth in Tanzania: Study protocol for the evaluation of the MAMA intervention. Res Sq. Published online January 30, 2023:rs.3.rs-2285235. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-2285235/v1

16. QDSTM – Overview – NOVA Research Company. Accessed March 3, 2023. https://www.novaresearch.com/products/qds/

17. van de Wijgert J, Padian N, Shiboski S, Turner C. Is audio computer-assisted self- interviewing a feasible method of surveying in Zimbabwe? Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29(5):885-890. doi:10.1093/ije/29.5.885

18. Neufeld SAS, Sikkema KJ, Lee RS, Kochman A, Hansen NB. The Development and Psychometric Properties of the HIV and Abuse Related Shame Inventory (HARSI). AIDS Behav. 2012;16(4):1063-1074. doi:10.1007/s10461-011-0086-9

19. The EquityTool. Equity Tool. Accessed March 8, 2023. https://www.equitytool.org/the-equity-tool-2/

20. Murungi T, Kunihira I, Oyella P, et al. The role of religious leaders on the use of HIV/AIDS prevention strategies among young people (15–24) in Lira district, Uganda. PLOS ONE. 2022;17(10):e0276801. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0276801