Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine

97 Examining the role of rurality in access to long-acting reversible contraception in Utah, Idaho and Nevada

Maegan Thomas and Rebecca Simmons

Faculty mentor: Rebecca Simmons (Obstetrics & Gynecology, University of Utah)

Abstract

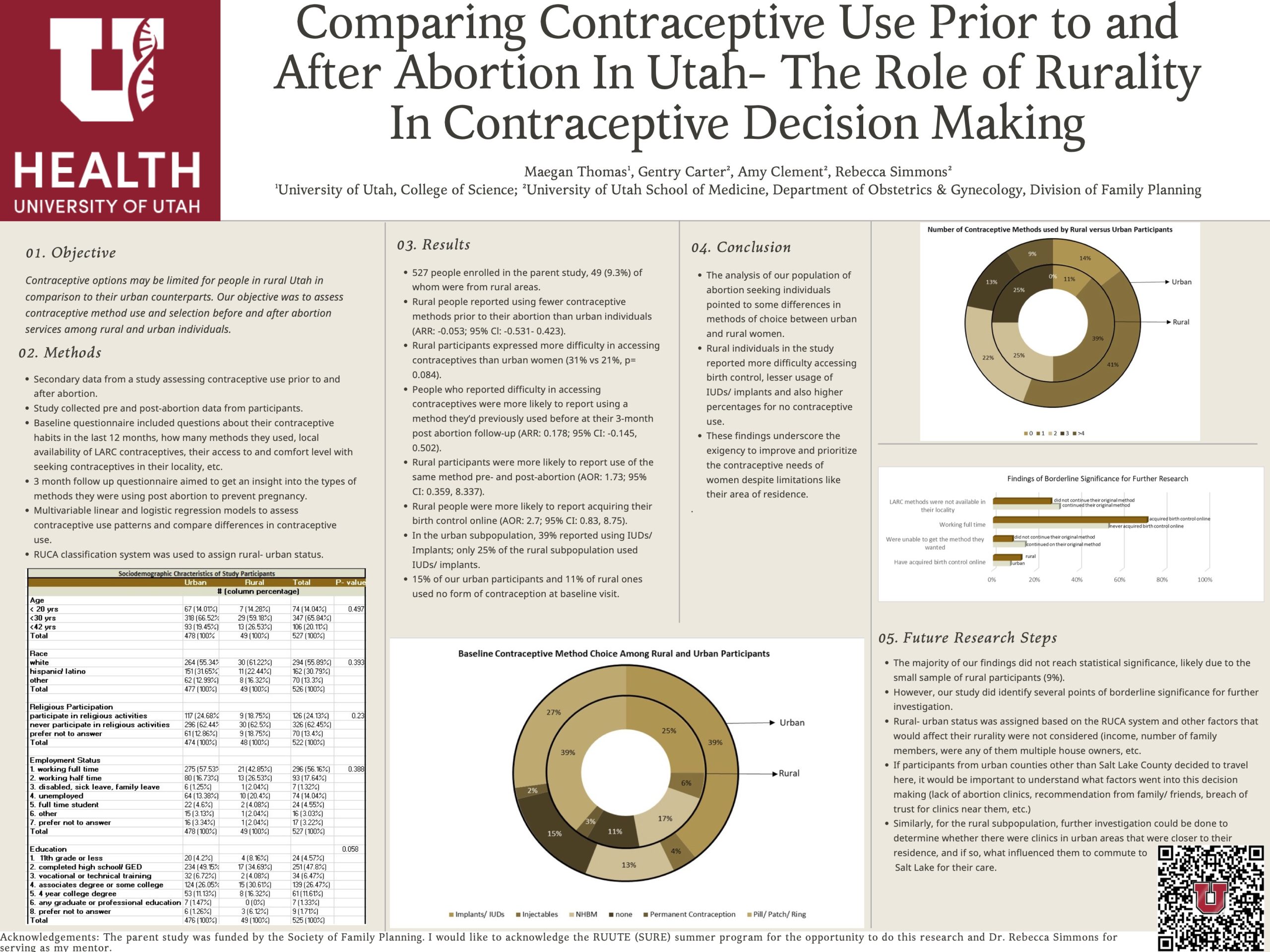

Contraceptive options may be limited for people in rural counties in comparison to their urban counterparts. Geographic disparities in contraceptive access continue to impact people’s ability to obtain their preferred methods of contraception. We examined the association between rurality and current use of/interest-in long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) in three western states with higher proportions of individuals living in rural areas.

A total of 2,603 individuals ages 18-50 from Utah, Idaho and Nevada were recruited to participate in a population-based survey examining sexual and reproductive health topics. We conducted multinomial logistic regression analyses to assess associations between rurality and participant interest in using or report of ever-LARC use.

Among those recruited, 1668 (64%) provided responses regarding LARC use. Participants from small town areasand rural areas (OR: 3.48; 95% CI: 1.03,11.8; p-value: 0.045) were significantly more likely than metropolitan participants to report wanting to use a LARC method, but being unable to do so due to access barriers. However, rural participants were also more likely to report currently using a LARC method than non- rural individuals (AOR: 3:43; 95% CI: 1.45, 8.14; p-value: 0.005). No significant differences were found between states in either demand forLARC methods or current use of LARC methods.

Both current LARC use and unmet need for LARC methods were higher in rural populations, suggestingcharacteristics of these methods have particular appeal for people who typically need to travel farther for medical care.

Introduction

Access to health care services is indisputably one of the major factors that determine the quality and capacity of services that individuals from different backgrounds get. In recent years, there has been a growing interest in understanding the various factors that influence access to healthcare services, particularly in the context of reproductive health. One intriguing aspect of this exploration is the examination of how rurality, or the rural- urban divide, plays a significant role in access to long-acting reversible contraception (LARC). This study focuses on the states of Utah, Idaho, and Nevada, providing insight into the prevalence of different contraceptive knowledge and behaviors. Unique challenges and disparities may affect different residents and this disparity may be even more pronounced based on rurality. Community based distribution of contraceptives have shown to result in greater increase in contraceptive use by rural women than urban women (Thompson et al.,2021). This points to the scope for improvement of contraceptive access in rural areas. Our study was also focused on addressing this contraceptive gap that may possibly point to greater unmet need for contraception in rural areas. By delving into the intersection of geography and reproductive health, we aim to contribute valuable insights that can inform policies and interventions, ultimately fostering more equitable and accessible reproductive healthcare for all residents in these states.

There’s a complex, yet close-knit relationship between contraceptive use and abortion. The bulk of abortions performed result from unintended pregnancies, the majority of which are the result of not using any form of contraception (70% reported no use of contraception; 30% reported use of some form of contraception prior to the unintended pregnancy) (Masiano et al.,2019). Studies show that when people receive the method they want, they tend to use contraception consistently (Gawron et al.,2020).

Understanding contraceptive access, particularly use of preferred methods, can help identify opportunities to support improvements to method offerings in different environments. Our preliminary study explores this intersection of contraception and abortion as they relate to rurality. Participants from various parts of Utah were asked about local obtainability of long-acting, reversible (LARC) contraceptives, their comfort level in availing birth control services, the type of contraceptive method used pre versus post abortion, etc.

The distribution of abortion care clinics in US counties significantly influence the rates of abortions. An increase in travelling distance from 5 miles to >120 miles was associated with a tremendous decrease in median abortion rates from 21.1 to 3.9. (Madden et al.,2011). This decline is in tandem with an increase in unmet abortion care needs of rural women who are then forced to travel longer distances to seek care (Thompson et al.,2021). This asserts the need for research that routinely evaluates people from different regions for their awareness of the facilities around them in order to understand general quality of basic healthcare services. Although there is literature that suggests that having an abortion influences the method of contraceptive choice among women, there have been very few studies that compare pre vs post abortion contraception and whether or not the abortion affected the way women take decisions about contraception. Women with recent abortions who received delayed start post abortion contraception resembled women without a recent history of abortion in their selection of contraceptive method (Madden et al.,2011). However, women with recent abortions who got immediate post abortion contraception were three times as likely to select IUDs as contraception (Madden et al.,2011). Thus, our preliminary study assessed contraceptive method use and selection before and after abortion services among rural and urban individuals. We measured the average number of methods used by rural and urban individuals. We also checked for patterns in continuation versus change of original birth control method, stratified by rurality. Women in general tend to switch to a different method after an abortion (Madden et al.,2011), but there’s no data as to how this changes with rurality. Telemedicine is highly encouraged to break through some of the barriers that rural communities face in getting the care they want (Masiano et al.,2011)(Rodriguez et al.2021). However, people who use telemedicine to mitigate lack of access in rural areas are still unable to get provider LARC methods like IUDs, implants, and depo shot. We anticipate that more rural residents would have used online methods to gain birth control compared to urban residents who may find it easier to just obtain birth control at a much more reasonable commuting distance.

A similar study done in Cambodia examined sociodemographic factors that may influence continuation of contraceptives post abortion (Adelman et al.,2019). Women with prior contraception use in Cambodia are twice as likely to continue using effective contraception post abortion compared to women who reported no use of contraception before their abortion. Women in rural areas are predicted to continue contraceptive methods more often that women in urban populations. Given that prior studies show a positive correlation between poor access to contraception and increased rurality, it’s important to help facilitate availability of contraceptive services. Our study prioritizes contraceptive availability among rural and urban citizens and tries to evaluate difference in desirability to use a LARC method pre versus post abortion.

There tends to be increased use of IUDs in urban areas than in rural ones (Lilja et al.,2021). This data corresponds with an increase in availability and accessibility of copper IUDs as well in urban areas. Bridging this difference in use of IUDs is an area of interest for the medical community, especially because of the high efficacy and high rates of continued use of IUDs compared to other methods (Burk and Norman,2019).

While the high efficacy of LARC methods, makes it a preferred method to avoid unintended pregnancies, access to these methods may be highly limited in rural areas. Owing to the barriers to contraceptive availability in rural areas, we hypothesize that women in rural areas may report using fewer number of contraceptive methods compared to in urban areas. Studies have linked LARC use with rurality, and there was no difference in LARC use in rural versus urban populations, but there was increased use of IUDs in urban areas. In addition to abortion, we wanted to measure if rurality was also a contributing aspect in women’s contraceptive choice. We expect to see differences in contraceptive method selection by area of residence.

As societies evolve and healthcare landscapes transform, understanding the multifaceted dynamics influencing contraceptive decision-making becomes increasingly crucial. One compelling facet of this exploration is the examination of the role of rurality in shaping individuals’ choices regarding contraception, with a focus on three western states characterized by higher proportions of rural residents.

Methods

This study illustrates the results of two closely related surveys that study the effect of rurality on birth controlaccessibility and use. The preliminary study examined the role of rurality in contraceptive decision-making, prior to and after abortions in Utah. The main study compares use and access to LARC, based on rurality in Utah, Nevada and Idaho.

We utilized data from the preliminary study to expand our research to include a larger sample size that further investigates the significance of the observed results. Our objective was to quantify the discrepancy in contraceptive method use and selection by examining how state demographics, barriers to access, and other local factors may playa role in contraceptive decision-making.

Preliminary Study

We used secondary data from a survey that was administered to 527 abortion seeking women in Utah. Weconducted logistic regression analyses and compared differences in contraception use, and continuation of a method type pre versus post abortion for rural and urban women.

Current Study

In 2022, a total of 2,603 individuals ages 18-50 were recruited from Utah, Idaho and Nevada to participate in a population-based survey examining sexual and reproductive health topics. The survey was conducted by phone and email to ensure maximum response. We conducted multinomial logistic regression analyses to assess associations between rurality and participant interest in using or report of LARC use. We examined rurality based contraceptiveavailability and behavior and compared our findings to the preliminary survey in Utah to look for correspondence. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to assess contraceptive patterns and compare differences in contraceptive use between the rural and urban groups.

We used the RUCA system to assign rural- urban status here as well to maintain consistency in categorization. We collected county- level data from each state and hence assigned an “overall” RUCA code based on the most common code associated with the respective county. We then collapsed small towns and rural areas into our “rural” population and compared it to our metropolitan “urban” group. Our initial multinomial regression model had three categories for rurality, namely, ‘Metropolitan’, ‘small town’, and ‘rural’. In these models, the directionality of the model suggested that increasing rurality was associated with an increase in desire to want a LARC method but being unable to access it. However, our confidence intervals were too wide, due to the smaller number ofrespondents meeting rural or small town classification. In order to create more stability in our model, we collapsed the ‘small town’ and ‘rural’ groups into a single variable that we represent as ‘small town and rural areas’ in our tables.

Results

Preliminary results

527 people were enrolled in the parent study, 49 (9.3%) of whom were from rural areas. Rural people reported using fewer contraceptive methods prior to their abortion than urban individuals (ARR: -0.053; 95% Cl: -0.531- 0.423). Rural participants expressed more difficulty in accessing contraceptives than urban women (31% vs 21%, p= 0.084). People who reported difficulty in accessing contraceptives were more likely to report using a method they’d previously used before at their 3-month post abortion follow-up (ARR: 0.178; 95% CI: -0.145, 0.502). Ruralparticipants were more likely to report use of the same method pre- and post-abortion (AOR: 1.73; 95% CI: 0.359,8.337). Rural people were more likely to report acquiring their birth control online (AOR: 2.7; 95% CI: 0.83, 8.75). In the urban subpopulation, 39% reported using LARC only 25% of the rural subpopulation used LARC. 15% of our urban participants and 11% of rural ones used no form of contraception at baseline visit.

Main results

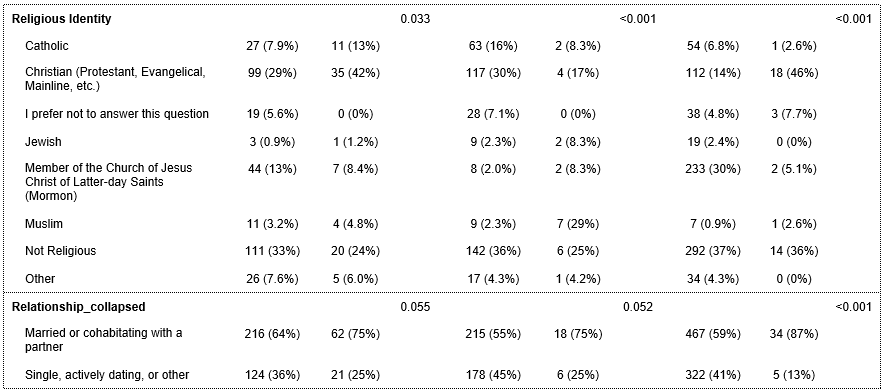

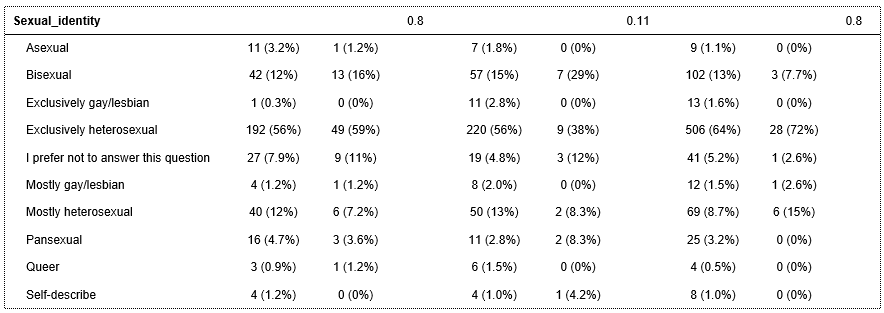

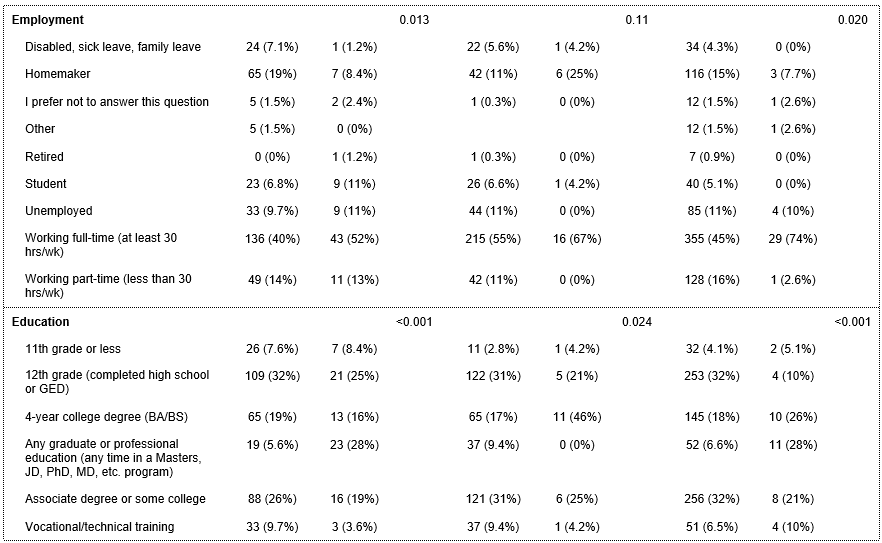

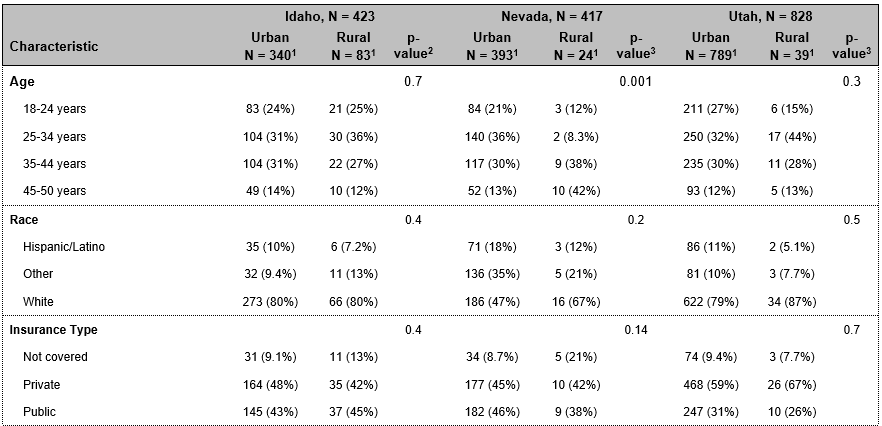

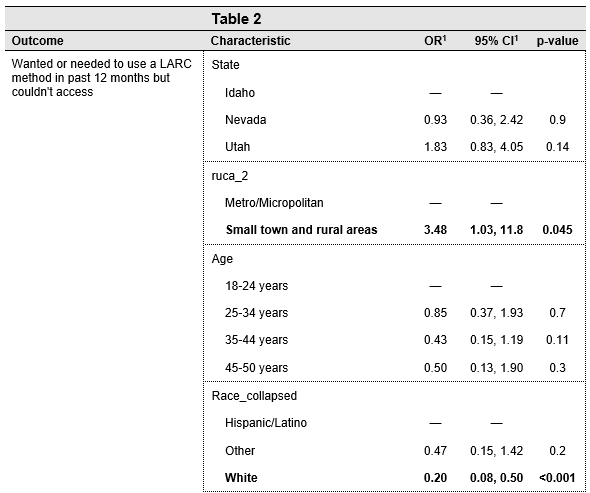

A total of 1668 people (Idaho, N=423; Nevada, N=417; Utah, N=828) were included in our final analysis. This consisted of 146 “rural” residents (8.75%) as determined by the RUCA classification system and about 56.8% of them were from Idaho. The sociodemographic characteristics of our survey respondents are provided in Table 1. We had a comparably similar characteristic distribution of people among the three states. A majority of our respondents self-identified as being white (71.7%), married or living with a partner (60.6%), mostly heterosexual individuals (60.1%) who were working full time (47.6%) and had at least a high school diploma (30.8%). A greater number of rural residents in Idaho and Utah reported identifying as conservative (Idaho: Urban conservatives vs rural conservatives= 27% vs 49%, p=<0.001; Utah: Urban conservatives vs rural conservatives= 33% vs 18%, p=0.01) in their political description whereas more urban residents of these two states self-identified as liberal (Idaho: Urban liberals vs rural liberals= 24% vs 16%, p=<0.001; Utah: Urban liberals vs rural liberals= 25% vs 18%, p=0.01). Table 2 contains our multinomial regression results assessing whether reported rurality is associated with ever LARC use. Based on the results of our multinomial regression model in Table 2, rural participants in all states were three times as likely to report wanting a LARC method but being unable to use it because of access barriers (OR: 3.48; 95% CI: 1.03,11.8; p-value: 0.045).

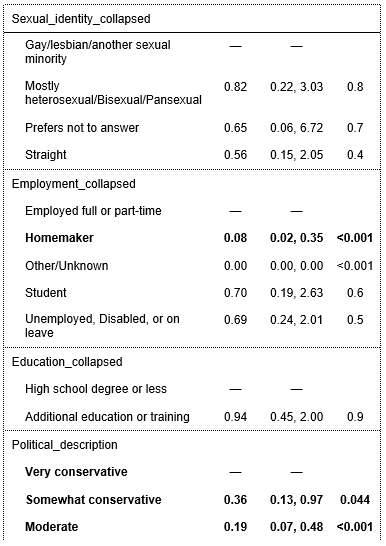

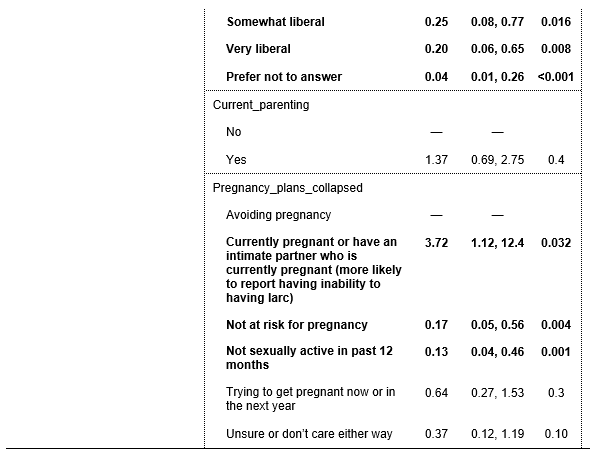

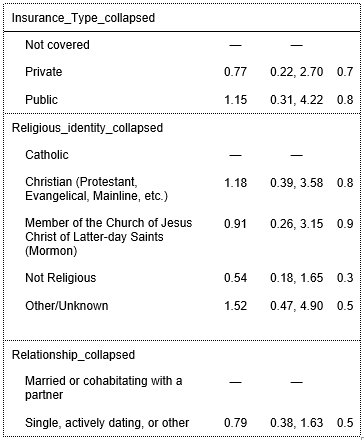

Those who reported have difficulty accessing LARC methods were less likely to be white (OR: 0.20; 95% CI: 0.08,0.5; p-value: <0.001) and less likely to be homemakers (OR: 0.08; 95% CI: 0.02,0.35; p-value: <0.001). People who showed desire for LARC but couldn’t access it due to barriers were less likely to identify as “somewhat liberal” (OR: 0.25; 95% CI: 0.08,0.77; p-value: 0.016) and “very liberal” (OR: 0.20; 95% CI: 0.06,0.65; p-value: 0.008), compared to individuals who identified as “somewhat conservative” and “very conservative.” People who reported being currently pregnant or having an intimate partner who was currently pregnant were more likely to report having inability to access LARC when compared to those avoiding pregnancy (OR: 3.72; 95% CI: 1.12,12.4; p-value: 0.032).

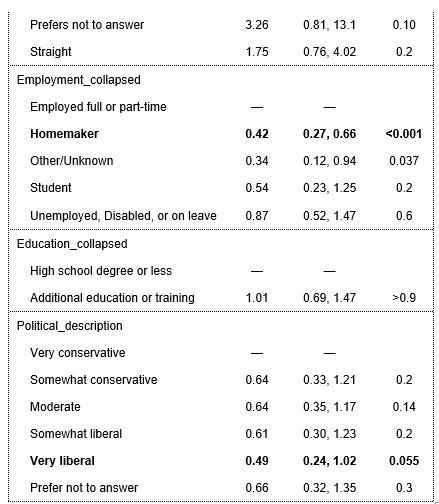

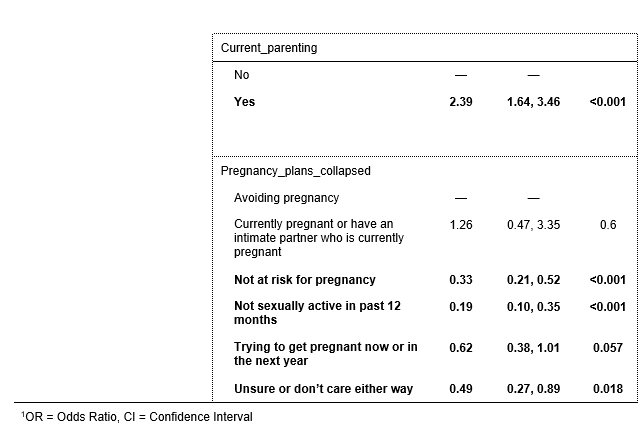

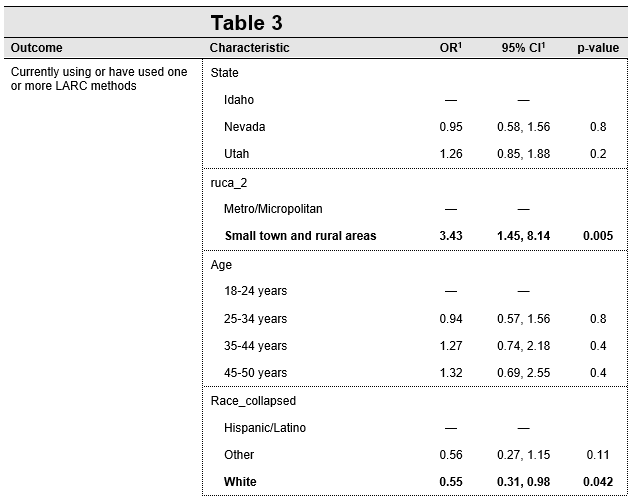

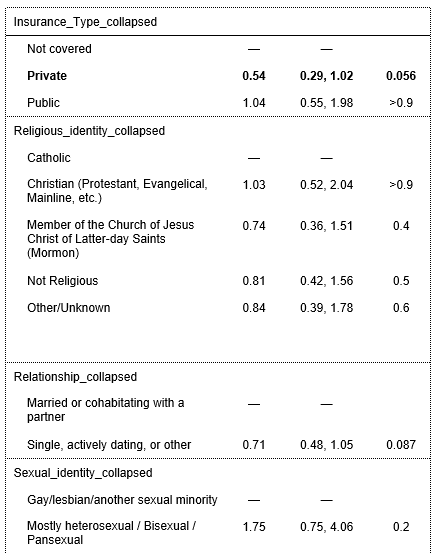

Regression results in Table 3 show that compared to metropolitan respondents, small town and rural respondents were three times more likely to be currently using a LARC method (AOR: 3:43; 95% CI: 1.45, 8.14; p-value:0.005). White participants (OR: 0.55; 95% CI: 0.31,0.98; p-value: 0.042), those who used private medical insurance (OR: 0.54; 95% CI: 0.29,1.02; p-value: 0.056), and homemakers (OR: 0.42; 95% CI: 0.27,0.66; p-value: 0.001) were less likely to have ever used a LARC method or to currently be on a LARC method. Those whoidentified as being very liberal were less likely to currently be using LARC (OR: 0.49; 95% CI: 0.24,1.02; p-value: 0.055). Participants who were currently parenting were twice as likely to report either currently using or ever having used a LARC method (OR: 2.39; 95% CI: 1.64,3.46; p-value: <0.001). People reported not being at risk of pregnancy (OR: 0.33; 95% CI: 0.21,0.52; p-value: <0.001) and those who are have not been sexually active in the last year (OR: 0.19; 95% CI: 0.10,0.35; p- value: <0.001). are less likely to report ever having used LARC.

Discussion

The results of our primary study show that rurality is a determining factor when it comes to contraceptive access and availability. The survey results demonstrate that while desirability of LARC methods is highest in rural and small town areas, access barriers cause an increase in unmet contraceptive need in these non- urban areas. Comparedto the metropolitan group, our rural and small town respondents had greater current use of a LARC method. Ruralityis strongly related to wanting a LARC method but not being able to access. That is, the desire to get a LARC method, but being unable to increases as rurality increases. Also, rural individuals were also more likely to be currently using a LARC method. This indicates that rural areas may have stronger desires for LARC methods because they either want it and can’t have it or are using it. Our preliminary survey results represent a similar pattern of higher LARC use, but also greater difficulty in accessing contraceptives than urban respondents. Both our preliminary and primary study results demonstrate that when stratified by rurality, rural individuals report greater use of more effective contraception options, but they also indicate experiencing more barriers that limit access and care. There’s no current literature that studies differences in contraceptive use based on rurality in the US, but our results support the findings of similar studies conducted in Ethiopia (Wondie et al.)and Bangladesh (Hossain et al., 2024) where use of longer acting methods was higher among rural women, but overall use of any form of contraception was higher among urban women.

There’s an enormous barrier to getting birth control due to lack of primary care and OBGYN providers in rural areas (The Supply and Rural-Urban Distribution of the Obstetrical Care Workforce in the U.S. – WWAMI RHRC). This could explain some of the trend of large unmet need in rural areas that we observed in our analysis. More than a million women in need in the US reside in a county thatdoesn’t even have a single health center that offers the full range of contraceptive methods and over 19 million live in contraceptive deserts (Contraceptive Deserts 2024 | Power to Decide). The lack of federally qualified health centers in rural areas that provide contraception and the lack of rural providers make it extremely difficult for women from underserved communities to get their method of choice.

Based on table 2 results, people who were currently pregnant were three time more likely than people avoiding pregnancy to report wanting a LARC method in last 12 months, but being unable to access. There’s literature that shows that people who use the birth control method they want are less likely to have an unintended pregnancy (Gomez et al.,2024).

This inability to have LARC in spite of wanting it may suggest an unintended current pregnancy among our study participants. Lack of access to contraception is a public health crisis that affects millions of people in the United States. While contraceptive initiatives have improved the education surrounding contraceptive use, there are several other factors that play into this unavailability that include cost of procurement, provider and clinic shortages, etc. Our findings highlight that barriers to contraceptive access affect contraceptive use, and hence, efforts should be made to improve and prioritize the contraceptive needs of individuals even beyond barriers like their area of residence. Desirability tends to be overshadowed by inaccessibility when it comes to actual use of contraception especially in rural communities.

Our sampling frame was a strength of our study since results were obtained by a population survey which allowed a wide capture of both rural and urban responses. Questions about contraceptive use and comfort, as well as education surrounding family planning were more up to date. This is a longitudinal study, and hence, would allow us to measure change is parameters with time in the future.

The study investigates the lesser know discrepancies in contraceptive use among rural and urban individuals, but there are also limitations in the study that must be accounted for. We included both male and female survey respondents in our analysis. Males’ responses may be skewed since there are directly reporting their own experience and since male knowledge of their partner’s contraceptive habits may be incomplete or biased. We did not have a large enough sample in frontier populations and hence we combined our “rural” and “small town” groups for statistical precision. This prevented a more granular analysis that could have potentially given us a gradient for rurality versus LARC use. Rural- urban status was assigned based on the RUCA classification system that accounts for population density, commuting distances and urbanization (USDA ERS – Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes,2023), but other factors that would affect rurality were not considered (income, number of family member, if any of them were multiple home owners, etc).

Individuals in rural areas show desire to use more effective forms of contraception, however several factors limit their access to a comprehensive set of options. Further research could help address initiatives that cater to the contraceptive needs of people by diverting more resources to contraceptive deserts.

Table 1: Demographic Table

|

Table 2: LARC Desirability

|

Table 3: LARC Use

|

References

Adelman, Sara, et al. “Predictors of Postabortion Contraception Use in Cambodia.” Contraception, vol. 99, no. 3, Mar. 2019, pp. 155–59. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2018.11.010.

Burk, Jillian C., and Wendy V. Norman. “Trends and Determinants of Postabortion Contraception Use in aCanadian Retrospective Cohort.” Contraception, vol. 100, no. 2, Aug. 2019, pp. 96–100. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2019.04.013. Contraceptive Deserts 2024 | Power to Decide. https://powertodecide.org/what-we- do/contraceptive-deserts. Accessed 17 Mar. 2024.

Gawron, Lori M., et al. “The Effect of a No-Cost Contraceptive Initiative on Method Selection by Women with Housing Insecurity.” Contraception, vol. 101, no. 3, Mar. 2020, pp. 205–09. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2019.11.003.

Gomez, Anu Manchikanti, et al. “Estimates of Use of Preferred Contraceptive Method in the United States: A Population-Based Study.” The Lancet Regional Health – Americas, vol. 30, Feb. 2024. www.thelancet.com,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2023.100662.

Hossain, Sorif, et al. “Contraceptive Uses among Married Women in Bangladesh: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses.” Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, vol. 43, Jan. 2024, p. 10. PubMed Central,https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-024-00502-w.

Lilja, Kristen, et al. “Clinical Availability of the Copper IUD in Rural versus Urban Settings: A Simulated Patient Study.” Contraception: X, vol. 3, 2021, p. 100059. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conx.2021.100059.

Madden, Tessa, et al. “Comparison of Contraceptive Method Chosen by Women with and without a Recent History of Induced Abortion.” Contraception, vol. 84, no. 6, Dec. 2011, pp. 571–77. PubMed Central,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2011.03.018.

Masiano, Steven P., et al. “The Effects of Community-Based Distribution of Family Planning Services onContraceptive Use: The Case of a National Scale-up in Malawi.” Social Science & Medicine (1982), vol. 238, Oct. 2019, p. 112490. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112490.

Rodriguez, Maria I., et al. “Association of Rural Location and Long Acting Reversible Contraceptive Useamong Oregon Medicaid Recipients.” Contraception, vol. 104, no. 5, Nov. 2021, pp. 571–76. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2021.06.019.

The Supply and Rural-Urban Distribution of the Obstetrical Care Workforce in the U.S. – WWAMI RHRC.https://familymedicine.uw.edu/rhrc/publications/the-supply-and-rural- urban-distribution-of-the-obstetrical-care-workforce-in-the-us/. Accessed 17 Mar. 2024.

Thompson, Kirsten M. J., et al. “Association of Travel Distance to Nearest Abortion Facility With Rates of Abortion.” JAMA Network Open, vol. 4, no. 7, July 2021, p. e2115530. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.15530.

USDA ERS – Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data- products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes/. Accessed 21 Mar. 2024.

Wondie, Kindu Yinges, et al. “Rural–Urban Differentials of Long-Acting Contraceptive Method Utilization Among Reproductive-Age Women in Amhara Region, Ethiopia: Further Analysis of the 2016 EDHS.” Open Access Journal of Contraception, vol. 11, Aug. 2020, pp. 77–89. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.2147/OAJC.S255551.

Appendix A- Preliminary StudyPoster (presented August 2022)