School for Cultural and Social Transformation

4 Marginalized Survivors’ Experiences Accessing Campus or Community Resources that Address Gender-Based Violence

Emma Taylor

Faculty Mentor: Elizabeth Archuleta (Ethnic Studies, University of Utah)

Many academic institutions, both undergraduate and graduate, persist in neglecting the intersections of race, gender identity, immigrant status, disability status, LGBTQIA+ affiliation, first-generation and international student status and their impact on survivors’ access to and utilization of campus and community resources for gender-based violence. This research investigated the experiences of survivors with marginalized identities when accessing university and community resources and their perspectives on mandatory reporting. It provided a space to center their recommendations for enhancing or modifying campus resources. Through highlighting the survey and interview responses of 33 undergraduate and graduate survivors with marginalized identities, this study endeavors to amplify their voices and pave the way forward for changes to ensure greater accessibility and cultural competence in campus and community resources. Through using qualitative narrative and thematic analysis of survivors’ experiences, various patterns emerged, delineating barriers within and beyond a research-one university campus situated in the Intermountain West. The patterns include economic barriers; frustrations stemming from a lack of diversity within campus resources; insufficient support and follow-up; apprehension towards police, and emotions of fear, anger, and shame. Additionally, few survivors recounted positive experiences, with the majority expressing discontent with federal mandatory reporting requirements. Moreover, survivors provided recommendations about the necessity of improving resources, advocating for improved training for mandatory reporters, enhancing diversity within campus resources, heightening efforts to raise awareness of available resources among students, increasing funding for resources, and offering support for secondary trauma survivors.

Keywords: marginalized identities, gender-based violence, lack of diversity, police, mandatory reporting requirements, and culturally competent resources.

Literature Review

Introduction and Intersectionality

Kimberle Crenshaw, in 1989, pioneered the term and theoretical framework, intersectionality, to understand how one’s social and political identities come together to form different modes of privilege and marginalization. For decades, other scholars have built upon Crenshaw’s work, as it reveals how society and institutions frequently base their policies on the white experience, neglecting women of color and other marginalized groups (Crenshaw, 1989, pp. 2-3; Crenshaw, 1991, p. 26).Intersectionality and sexual violence are deeply entwined. Marginalized groups, such as Indigenous, Black, Latinx, Asian American, immigrant, and LGBTQIA+ communities, face higher rates of sexual exploitation and violence. However, resources frequently overlook the ongoing harm inflicted on marginalized communities by legacies of oppression (Gomez, Cerezo, & Beliard, 2019, p. 4; Gill, 2018, p. 2). When institutions and colleges lack culturally competent resources, it has life- changing consequences for marginalized survivors, such as survivors avoiding therapists because they are not well-versed in cultural differences or generational trauma (Harris, 2020, p. 16-17). Additionally, as the history of genocide, colonialism, slavery, segregation, and dehumanization have led to stereotypes of women of color’s bodies as “unpure,” leading to dominant conceptions that they “cannot” be assaulted (Crenshaw, 1991, p. 38). Hence, the enduring legacies of discrimination and dehumanization can deter survivors of color from utilizing campus resources.Higher education institutions seldom integrate intersectionality into sexual assault prevention and awareness training for university staff. This exacerbates resource gaps, such as the absence of culturally competent mental health counselors for survivors with marginalized identities. Additionally, institutional sexual violence policies often frame gender-based violence as a “color-blind phenomenon,” disregarding the distinct experiences of racial groups with sexual violence. Merely belonging to certain racial groups increases the likelihood of being targeted by perpetrators and reduces access to resources (Harris, 2020, p. 2). For example, campus resources supporting survivors of gender-based violence at a research-one university located in the Intermountain West often deploy a one-size-fits-all approach, overlooking the impact of historical oppression and violence on students’ ability to access these resources. While the campus resources support survivors of gender-based violence and staff members to discuss survivors’ options, a women’s resource center, a counseling center, and victim survivor advocates are the only campus services that offer confidential therapeutic services. Another counseling center provides support groups for marginalized communities, specifically for men of color, the LGBTQIA+ community, and BIPOC students, but lacks one for survivors. Furthermore, there are concerns that this counseling center inadvertently harms marginalized communities due to counselors’ oversight of historical and intergenerational trauma or colonial settler violence. In addition, a 2022 campus survey on sexual violence did not inquire about participants’ race, immigration status, disability status, international student status, and their impact on reporting willingness. Intersectionality is crucial for understanding barriers faced by survivors and is a tool that can help universities ensure that resources effectively support those with intersecting marginalized identities.

How Marginalized Survivors Experience Sexual Violence

On college campuses across the United States, rates of sexual violence are uncommonly high. Perpetrators sexually assault communities of color and LGBTQIA+ folks disproportionately, but marginalized survivors often avoid seeking resources (Harris, 2020, p. 12). Dominant narratives about marginalized survivors’ unwillingness to access resources must be reframed as a continuance of “white supremacy, patriarchy, colonialism, and economic exploitation of marginalized communities,” which is vital to ensuring that resources and service providers can adequately serve marginalized communities (Sokoloff & Dupont, 2005, p. 9).

While most marginalized groups face access barriers, their experiences are not a monolith. For example, members of the LGBTQIA+ community often face rampant homophobia, which may cause them to fear reporting due to potential negative responses from police, family, social services, and battered women’s organizations (Sokoloff & Dupont, 2005, p. 7). Other marginalized survivors, such as Asian Americans, often feel that law enforcement officers will not believe them because of erroneous stereotypes that paint them as “hypersexual, passive, and not the white norm” (Harris, 2020, p. 4). In addition, many Latinx, Indigenous, and Black women feel uncomfortable turning to law enforcement after an assault because of an oppressive and brutal history with police and state actors (Gomez, Cerezo, & Beliard, 2019, p. 3). Gomez et al. (2019) elaborated that, throughout history and presently, many police officers assault “Latinx, Native, Black, and other women of color…without legal consequences” (p. 3). Abuse at the hands of law enforcement is one factor of many that often convinces women of color not to report and relays a message that they have “little value” (Gomez, Cerezo, & Beliard, 2019, p. 4). According to Bryant-Davis et al. (2009), other survivors, such as Asian American and Pacific Islander survivors, often avoid seeking resources as they feel that available support systems will not account for “religious beliefs, social stigma, and fear of shaming one’s self and one’s family” (p. 337). Furthermore, African American, Latina, Asian American, and Indigenous survivors face other barriers, which include “language barriers, distrust of agencies, discriminatory treatment by agencies, and socially perpetuated…victim-blaming rape myths” (Bryant-Davis, Chung, & Tillman, 2009, p. 347). Homophobia, dehumanization, stereotypes, and institutions devaluing marginalized survivors’ lives increase their hesitancy to report.

Dehumanizing stereotypes plague marginalized survivors, shaping who society deems deserving of support (Wieskamp & Smith, 2020, p. 7). A Latina survivor argued that the #MeToomovement, founded by Tarana Burke to bring together women of color survivors, was “co-opted” by white feminism, as it does not “center Women of Color at all” (Harris, 2020, p. 9). According to Harris (2020), the survivor argued that such narratives, in which society deems white cis-gender women as the “only acceptable survivors,” influenced her not to report her assault or seek resources, as she explained, “We are Mexican. We do not fit the role of survivor. So, we are harder to believe because of that” (p. 9). In another example, racial affiliation also influences who society deems worthy of resources, as white women reported greater sympathy for other white survivors than for Latina rape victims, which stems from many factors, including erroneous stereotypes painting Latinas as flirtatious and hypersexual (Bryant-Davis, Chung, & Tillman, 2009, p. 13). Additionally, the constant stereotypes that plague marginalized survivors influence “our legal system, service providers, media representations” to “view only some survivors as legitimate victims” (Gomez, Cerezo, & Beliard, 2019, p. 4). As a result, dehumanizing messaging shapes marginalized survivors’ willingness to report and services’ willingness to address cultural differences.

Other marginalized survivors felt, especially if the perpetrator is within the same racial or ethnic group, they had to stay silent about their gender-based violence for fear of perpetuating racial stereotypes (Harris, 2020, p. 10). For example, a Southeast Asian survivor explained that, as women of color, they are “expected to swallow our own pain to move our community forward and to do it for our people” (Harris, 2020, p. 10). In another example, a Latina survivor avoided reporting her assault by a Latino man, as she felt it would exacerbate stereotypes that portray Latino men as performing and “encouraging hypermasculinity” (Harris, 2020, p. 10). But such erroneous stereotypes often operate as a double-edged sword for men of color who are survivors. They often face barriers to receiving support from services because society and institutions paint them as violent or hypermasculine, and women of color often avoid reporting their abuse for fear of perpetuating harmful stereotypes that dehumanize their respective communities (Harris, 2020, p. 10). Both sides must be acknowledged. Violent behavior and perpetrators exist and cause irrevocable harm within marginalized communities. Simultaneously, it is important to note how the characterization of men of color as violent is often rooted in racist ideologies and systems that seek to oppress and further dehumanize communities of color. This still impacts survivors today, as women, men, and LGBTQIA+ individuals are often hesitant to access services that do not address these historical legacies.

Furthermore, the strategic and systemic dehumanization of marginalized groups has occurred for centuries and continues to harm survivors. For example, Black women have long been portrayed as “more sexual,” and enslaved women and girls were routinely abused at the hands of their white slaveholders and subsequently had no path to legal accountability and justice (Gill, 2018, p. 560). According to Gill (2018), such racial and gendered oppression bleeds into today, as increased “policing in communities of color, mandatory arrests, escalation of violence and excessive force by police officers and other first responders to domestic violence calls” ensure that state actors continue to dehumanize Black survivors (p. 560). In addition, transgender and cisgender women of color, who are more likely to die as a result of domestic violence, cannot turn to the police to keep them safe, as state officers continue to exert disproportionate violence against communities of color (Gill, 2018, p.560). Similarly, often due to xenophobic laws and constant discourses of hatred and vitriol directed at immigrant communities by state actors, immigrant survivors typically distrust the state. As a result, many remain silent about their abuse or risk receiving support from institutions that might harbor xenophobic ideologies or wield “threats of deportation and family separation” against them and their families (Gill, 2018, p. 560).

Moreover, the state and medical officials often target individuals with disabilities, leaving them vulnerable to higher rates of gender-based violence committed against them. Disability scholar Eli Clare coined the term “body-mind” to resist the white, Western impulse to create a body/mind binary that sees each as distinct from the other. They argue that “entire body-minds, communities, cultures are squeezed into defective” categories by “medical, scientific, academic, and state authorit[ies]” as a way to exert power and control over these communities and to normalize the violence committed against them (Clare, 2017, p. 23). Throughout US history, any individual or community labeled as “defective” by the state could be targeted without “hesitation for eradication, imprisonment, institutionalization,” which often increased people with disabilities’ vulnerability to sexual abuse at the hands of law enforcement or other state and medical officials (Clare, 2017, p. 23).

For indigenous survivors, “war, conquest, rape, and genocide, and all of these depredations have disconnected them from both their land and their own bodies” (Deer, 2015, p. xv). According to Deer (2015), indigenous scholars, survivors, and activists have long highlighted that rape played “a significant role in past attempts to destroy indigenous nations” (xvi). Federal and state governments have continually diluted tribal power and created patchwork jurisdictions, allowing government actors to systematically fail and ignore the needs and safety of indigenous survivors (Deer, 2015, p. 43). In addition, according to a report by the Urban Indian Health Institute, “more than 95 percent” of the Missing and Murdered Native Women cases were not covered by national news (Urban Indian Health Institute, 2018, p. 20). The lack of news coverage renders indigenous survivors invisible, allowing racist stereotypes to characterize indigenous people as undeserving of support (Wieskamp & Smith, 2020, p. 7). Therefore, Wieskamp et al. (2020) found non-Native men feel they can violate women of color with impunity (p. 7). The disproportional rates of gender-based violence must be reframed within legacies of genocide, slavery, colonialization, and forced displacement, and therefore, the continued failure of resources to provide culturally competent support must also be understood as a continuation of those harmful legacies.

How College Resources Fail Marginalized Survivors

The Path Forward

Numerous insights emerge from the researched literature. Marginalized survivors have markedly different experiences from white people; many feel uneasy accessing resources that overlook their intergenerational trauma or cultural differences. Additionally, dominant stereotypes and a lack of news stories about women of color and LGBTQIA+ communities influence larger structures to dehumanize and devalue their experiences with sexual violence. Similarly, limited research explains how college students with marginalized identities experience sexual violence and their comfort level in accessing campus resources. By centering survivors with marginalized identities, this research aims to empower them to lead the way in improving how colleges address sexual violence. Most research regarding campus sexual assault has focused on those with privileged identities. However, research builds upon researchers and activists who have long prioritized survivors with marginalized identities. These advocates have aimed to spotlight LGBTQIA+ folks, people of color, immigrants, noncitizens, and people with disabilities and their histories of oppression and dehumanization in combating gender- based violence.

Research Design

Despite high rates of nondisclosure for marginalized college students, a university in the Intermountain West, where I conducted my research, employs a one-size-fits-all approach in its policies and practices toward survivors of sexual assault. This study, conducted through a survey and semi-structured interviews, examines this approach with dual objectives. Firstly, it explores whether marginalized groups such as LGBTQIA+ individuals, as well as Black, Indigenous, Latinx, Pacific Islander, Asian/Asian American, or other students of color (BIPOC), face unique barriers and concerns regarding disclosure of gender-based violence to campus-based resources. Secondly, it gathers suggestions from participants to develop policies and practices that prioritize the experiences of people with disabilities, LGBTQIA+, immigrant, noncitizen, first-generation, international, and BIPOC student survivors.

This study addresses three research questions:

RQ1: Do people with disabilities, LGBTQIA+, immigrant, noncitizen, first-generation, international, and BIPOC student survivors’ students face barriers when seeking campus-based or community help after experiencing sexual violence?

RQ2: What experiences have people with disabilities, LGBTQIA+, immigrant, noncitizen, first- generation, international, and BIPOC student survivors had when reaching out to campus-based resources?

RQ3: What policies and practices need to change to encourage marginalized students’ disclosure?

Following in the footsteps of similar research, I used the critical interpretive approach to explore the experiences of 33 undergraduate and graduate student survivors at a university in the Intermountain West. This approach encourages scholars to challenge societal and institutional structures of domination (Harris, 2020, p. 5). By adopting an interpretivist approach, my research centers on the lived experiences of survivors of gender-based violence, aligning with feminist

theoretical frameworks that emphasize the critical engagement with marginalized communities’ “lived social realities” and allows researchers to explore further the “sociopolitics of space, institutional

culture, safety, and security, amongst other concerns…through the worldview of participants” (Kiguwa, 2019, pp. 220-225). Additionally, by centering intersectionality and survivors with marginalized identities, this approach allows for a deeper exploration and understanding of differences among marginalized groups, providing critical insights into power dynamics as survivors narrate their own experiences (Kiguwa, 2019, p. 226). Moreover, in keeping in line with feminist and ethnic studies research traditions, which argue that “neutrality and objectivity” are impossible because research is, in fact, “a political act,” for several months, as I listened to and read survivors’ experiences, I increasingly became less and less of an objective observer. Instead, I carried a fraction of their rage, pain, sadness, fear, and resilience as they disclosed their stories and often opened themselves up to reveal their pain and anger at being failed or neglected by resources (Kiguwa, 2019, p. 226).

Research Sites

The entirety of my research occurred in a research-one university in the Intermountain West and resides in a heavily conservative state. As of 2024, this institution enrolled, over 30,000 students. Recently, the state legislature targeted Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion language and hiring practices at higher education institutions.

Participants

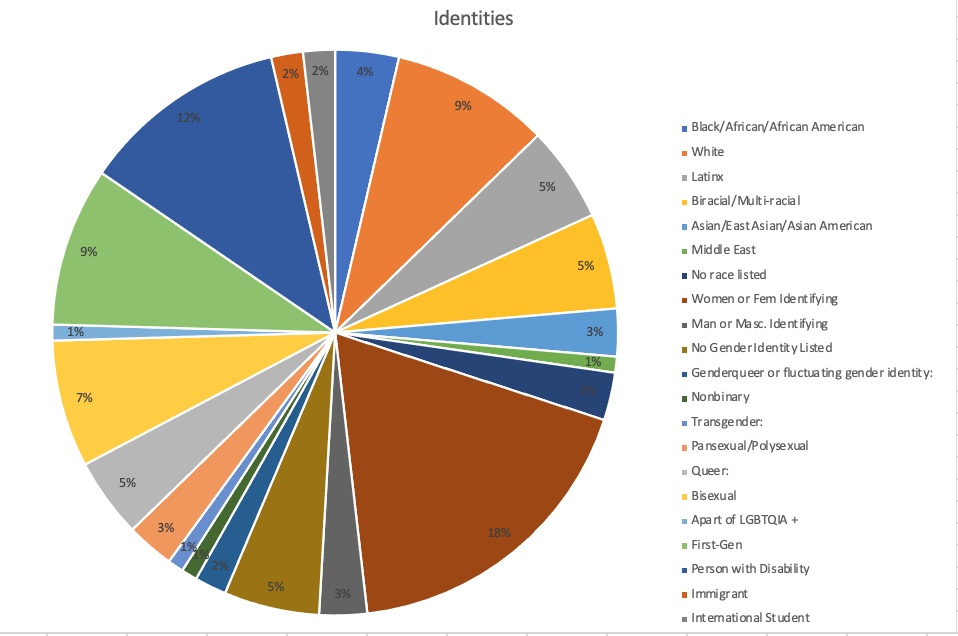

With the help of a faculty mentor and a community partner located in a campus center that supports student equity and belonging, we marketed the study in various ways, including social media campaigns, flyers, canvas messages, college newsletters, and the use of common spaces on campus to advertise the study. Several resource centers, faculty, relevant student groups, academic advisors, and various college deans were crucial in aiding outreach efforts, permitting flyers and 3×5 cards to be housed within their respective spaces or using social media to recruit participants. Participants were required to be current university students (undergraduate or graduate students), over 18 years old, and have experienced gender-based violence regardless of whether they utilized campus resources for survivors of sexual violence. We also asked that survivors identify with at least one of the following marginalized identities: African, African American, Black, Native, Indigenous, American Indian, Asian, Asian American, Latinx, Chicanx, Pacific Islander, Multiracial, LGBTQIA+, disabled, women and men of color, immigrant, noncitizen, first-generation, and international students. Given the centrality of connecting survivors’ identities with their experiences in our research, we asked participants to list their identities at the start of the survey and interview. Survivors represented diverse and multifaceted identities, identifying as Black, African, African American, white, Latinx, Asian, East Asian, Asian American, or unlisted race. Additionally, several survivors listed biracial or multi-racial identities, identifying as Afro-Latina, white and Mexican, white and Japanese, mixed race/ethnicities, or Pacific Islander, Asian American, and Filipino American. Survivors also listed their gender identity, identifying as women or female-identifying, male or male-identifying, or unspecified. Moreover, several survivors identified as members of the LGBTQIA+ community, including genderqueer, non-binary, transgender, pansexual, polysexual, queer, or bisexual. In addition, survivors identified as first-generation, immigrants, international students, or people with disabilities. Please see the pie chart below displaying the various identities of survivors who participated in this research project.

Data Collection

This research utilized a qualitative survey and offered a semi-structured interview for survivors interested in further discussion. Over four months, outreach efforts led 77 university survivors to view the survey, but ultimately, only 33 completed the survey. Additionally, five survivors consented to and completed in-person semi-structured interviews. All interviews were audio recorded with the survivor’s consent and typically lasted 20 to 30 minutes. Transcriptions were done verbatim by hand, and all interviews took place in a secure and confidential campus setting. Despite offering member-checking, none of the survivors who participated in interviews opted to review their transcripts.

Data Analysis

After I compiled and completed the survey and interview transcripts, I conducted three rounds of inductive thematic analysis and coding to identify themes and codes based on existing data. In one month, I familiarized myself with participants’ experiences, emotions, and stories. Afterward, I used Nvivo, a software program for finding codes and themes in qualitative and mixed-methods research, to assist with the data analysis of five interview transcripts and 33 survey responses. Over several weeks and through three rounds of analyses, I engaged in semantic coding, focusing on thematic similarities between survivors’ narratives that explained their emotions and inability to access specific resources (Harris, 2020, p. 6). Also, as the study’s purpose is to understand whether resources fail students with specific identities, engaging in thematic analysis allowed me to find themes from survivors’ differing stories and life experiences and help find related experiences among survivors with similar identities. Through inductive coding, several themes emerged regarding survivors’ feelings and experiences with campus support services, community resources, and federally mandated reporting, in which university employees must report students who disclose experiences with gender- based violence to authorities such as Title IX. After finding several themes within the data, I reviewed the codes to edit and ensure that survivors’ stories were adequately represented within their respective themes. In a fourth round of data analysis, using intersectionality as a central framework, I concentrated on survivors’ identities to generate quantitative data illustrating similarities in their experiences. In examining semantic themes and uncovering shared experiences tied to identities, the final stages of analysis were significantly influenced by intersectionality. This involved interpreting survivors’ stories within the “larger socio-historical context of structural inequality” generated by legacies of dehumanization and systemic oppression that affect how survivors with marginalized identities can access and effectively use campus and community resources (Harris, 2020, p. 6).

Positionality

I am a white cis-gender woman. Although I am not a survivor of gender-based violence, hearing the experiences of family and friends who are survivors and witnessing their frustration with inadequate support services inspired this project since it helped me realize the necessity of centering survivors with marginalized identities. As an intern, I observed the structural barriers preventing survivors with marginalized identities from accessing resources, such as fear of police and exhaustion from lengthy criminal justice procedures. I conducted this study under the guidance of a faculty mentor and community partner. Our aim was to create a platform for survivors with marginalized identities to share their stories and to emphasize their recommendations for enhancing the accessibility of campus and community resources. In addition, after completing my undergraduate degree, I plan to attend law school and work with marginalized folks worldwide, centering their experiences in the fight for human rights.

Findings

As the purpose of the study was to discover survivors’ experiences with and thoughts about community spaces, campus resources, mandatory reporting, and recommendations to improve resources, I divided the findings section into four parts and detailed themes found within each category.

Positive Experiences Accessing Campus Resources

Interpersonal Connections

While most survivors using campus resources had negative experiences, some reported positive ones. The breakdown of survivors who had positive on-campus experiences identified as white (18%), Latinx (9%), biracial/multi-racial (4%), women or fem identifying (18%), male or masc identifying (4%), no gender identity listed (5%), queer (14%), first-generation (9%), people with disabilities (14%), and immigrant status (5%). For example, a white, able-bodied queer woman stated, “I felt a comforting presence at [an on-campus women’s resource center] and felt safe going there first. I also felt safe at a [student wellness center]” (ST003). A white queer survivor with a fluctuating gender identity, said they felt supported by a women’s resource center, as they “helped me get through a lot” (ST001). Similarly, a Latino, first-generation survivor, wrote that his dean was “supportive and proactive” (ST021). Another, who accessed a women’s resource center survivor support group, stated, “I did not feel judged or did not feel like I could not talk to them. I felt understood.” However, the survivor later dropped out of school and, as a result, could not access campus resources (ST002).

Other survivors who felt adequately supported by campus resources often had prior connections with them. For example, one turned to on-campus survivor advocates because “I already knew about them,” but simultaneously stated, “I also kind of felt just like I did not really know where else to go” (ST004). Another wrote that they turned to on-campus survivor advocates, a counseling center, and a resource center supporting Black, African American, and African students for support because “I knew people working in those centers” (ST008). A heterosexual, white female survivor with chronic illness stated, “I received some help at the [student health center] because I know one of the doctors there” (ST013). While some survivors reported positive experiences on campus, most noted that their prior interpersonal connections were vital for these positive experiences.

Barriers to Accessing Campus-Based Resources

Economic Barriers

Survivors with diverse identities expressed challenges accessing campus resources, noting failures in addressing intersections of socioeconomic status, race, gender identity, and first-generation status. The majority of survivors who indicated economic barriers were members of marginalized communities, such as Black/African/African American (8%), Latinx (17%), women of fem identifying (25%), bisexual (8%), first-generation students (17%), a person with disabilities (17%), and an immigrant (8%). A bisexual Latina stated that her parents warned her against confiding in her aunt and grandparents about her experiences with gender-based violence or “they wouldn’t let me live here anymore” (ST011). Similarly, another survivor mentioned economic barriers while living on campus. When asked about their comfort with campus resources, they responded, “Initially, I did not feel safe contacting anyone, especially the police, because I thought they would judge me for my overdue tuition issues or evict me from my dorm that I had trouble paying the rent for” (ST012). An African American, first-generation, heterosexual, cis-gender student, and US citizen, also mentioned additional economic barriers and time-consuming processes hindering their healing, such as having to work with an income and accounting office to prove that their trauma from gender-based violence “was worthy enough for a withdrawal tuition refund, or [Satisfactory Academic Progress] hold removal,” which “was just continually retraumatizing” (ST012). Due to poor communication within accommodation departments, she contended that various offices caused her to relive “my trauma again and again” as “these offices…can’t communicate, or…victim blame” (ST012). Additionally, she relayed that campus parking enforcement fails to address the safety concerns of survivors. Her past experience with gender-based violence made her afraid of “losing” her parking spot and being forced to “park far away and walk back to my dorm by myself or park in a non- pass spot and get another parking ticket,” describing the stress and fear created by parking enforcement as “insurmountable” (ST012). Furthermore, she described the debilitating fear following their assault, as two “of my assaulters lived on campus.” However, due to fear of involving police, they could not access a safety plan, and one of the individuals who assaulted them “followed me to my car that I had to park on upper campus due to football crimson club taking over” their usual parking lot for the evening (ST012). An immigrant, single mother, full-time worker, and part-time student, described turning to a women’s resource center because she did not have “did not have insurance…So, that’s why I decided to go through the university.” Additionally, once she secured a job with health insurance, she chose to go to “a private counselor, specifically for my needs” (ST002). As evident from these survivors’ narratives, clear economic barriers emerge, including fear of eviction when seeking family support, stress due to parking enforcement’s neglect of survivors’ safety needs, and the limited options available due to the lack of private health insurance.

Feelings of Fear, Anger, and Shame

Survivors who felt comfortable sharing their stories often expressed anger, fear, and shame, which deterred them from accessing campus resources. This group of participants identified as Black/African/African American (5%), white (14%), biracial/multiracial (5%), no race listed (5%), women or fem identifying (9%), queer (5%), bisexual (9%), polysexual or pansexual (5%), genderqueer (9%), non-binary (5%), no gender identity listed (5%), first-generation student (5%), and a person with disabilities (19%). A bisexual Mongolian woman felt that they could not turn to resources because they felt that there “was not enough evidence” to warrant seeking help (ST007). Another survivor who identified as female and LGBTQIA+ wrote, “In my own experience and from what I have heard from friends, many people know about the resources that are out there, but they are either too scared to go to them, or they feel that they are not deserving of the help” (ST017). An “Asian-American, Pacific Islander, Filipino, Filipino-American, immigrant, heterosexual male” wrote that they were uncomfortable accessing campus resources “since I didn’t know if the incidents were big enough” (ST028). Similarly, a first-generation Asian American survivor stated, “I didn’t even realize it/chose not to believe it was a form of gender-based violence,” significantly delaying their ability to seek support services (ST019). As evident in the responses, more inclusive education is necessary for survivors to identify and seek assistance for gender-based violence, especially tailored for students with marginalized identities.Other survivors expressed fears about potential retribution from perpetrators if they reported their experiences of gender-based violence. For example, “a bisexual, disabled, first-generation student” admitted avoiding campus resources for fear of being compelled to file a police report, which could escalate the abuse (ST009). Another survivor stated that many survivors hesitate to report for fear of repercussions or the perpetrator discovering the report (ST029). A female survivor with “mixed race/ethnicities, straight, and disabled from multiple chronic illnesses” highlighted the fear of how the offender might react to the report, regardless of confidentiality (ST032). These fears indicate a systemic failure, as survivors lack trust in resources to ensure their safety and hold perpetrators accountable. This fear is closely linked to historical mistrust rooted in centuries of abuse by state actors, experienced by communities of color, people with disabilities, immigrants, and LGBTQIA+ folks.

Fear of Police

In many survivors’ accounts, particularly people of color or members of the LGBTQIA+ community, fear of the police was evident, along with discussions of their traumatic experiences upon encountering campus police. A white, heterosexual, disabled female with chronic illness, stated, “I don’t trust the [on-campus] police. Point blank. Almost entirely because of how they handled [a high profile] case” that was in the news (ST013). A polysexual/sapphic and genderqueer participant relayed that because they are “more visually queer, I feel uncomfortable approaching or being around police because I’m not sure they’ll support me” (ST020).

Others discussed the blatant lack of trauma-informed care, which in the words of one survivor, “The [on-campus police] said that their officers are trained on sensitivity and whatever, but I am like, that is just bullshit because when I went in” the officers blatantly disregarded their wellbeing (ST004). The survivor, hospitalized for treatment, requested no police involvement. However, the hospital staff failed to inform them about the need to make a statement. They described their interaction with campus police officers as “really insensitive.” They added that a female officer disclosed also being a victim of gender-based violence, “but it was just like in this way where she was brushing it off and saying [being a survivor of gender-based violence] does not matter” (ST004). Additionally, the male police officer’s discussion of his religious background immediately caused the survivor to feel “way less safe,” and they felt that the male officer “almost believed me less because it was like a girl-girl” sexual assault (ST004). A “Black, Woman, Afro-Latina, Cis, American, and Neurodivergent” survivor shared her traumatic experience with the campus police. She said, “they made me sit in the public lobby to recall about my assault in detail as well as immediately handing me off to [a community police department] and never checked in/followed up with me even though I had campus safety concerns” (ST008). Another survivor of color shared their view of police, stating, “I do not want the police harassing me over an issue they wouldn’t care to solve” (ST012). Similarly, another survivor mentioned the ineffectiveness of the campus police’s follow-up process as they “highly encouraged me to file a real report and were blowing up my phone. This made me withdraw completely from even considering filing a real report. A year later, I wish I had” (ST033). Consistent with prior research, survivors expressing fear of campus police included individuals identifying as Black/African/African American (9%), biracial or multi-racial (4%), white (13%), no race listed (4%), women or fem identifying (13%), genderqueer (9%), non-binary (4%), bisexual (9%), first-generation (9%), and persons with disabilities (22%). Furthermore, several directly linked their identities to their fear of interacting with police officers, worrying they wouldn’t be believed or adequately supported. Among those who interacted with campus police, all reported a lack of trauma-informed practices or sensitivity to survivors’ wishes and needs.

Lack of Diversity within Campus Resources

Many survivors expressed hesitancy or refrained from accessing resources that lacked staff who reflected their identities. A BIPOC survivor expressed distrust toward campus police due to their identity as a woman of color and “had a hard time finding black support in [a women’s resource center], or any resource center for that matter” (ST012). Another survivor, who, at the time of their assault, spoke only Spanish, stated it is “difficult to find resources” that retain bilingual mental health therapists (ST002). Still, she elaborated that, even as she turned to a women’s resource center survivor support group solely because she did not have health insurance, “I felt that I had community, even if it wasn’t in Spanish” (ST002). Yet, she maintained that the university’s lack of bilingual mental health professionals made finding resources difficult and that for other survivors who feel more comfortable speaking in their respective native language, “it is difficult if your first language is not English” to find resources. This creates a barrier for immigrant, non-citizen, and other multilingual survivors seeking help (ST002). Another survivor stated that “there is an impending reality that DEI programs and education would cease in the next few years,” which can further harm marginalized communities (ST028).

A LGBTQIA+ survivor experienced gender-based violence from an abuser who targeted other individuals in the LGBTQIA+ community. They stated that another survivor reached out to an on-campus LGBT resource center as they “felt comfortable with this specific” individual at the center (ST003). However, because of mandatory reporting requirements, “she could not really open up unless she was willing to open up and start a report” (ST003). Thus, despite survivors feeling safe enough to seek assistance from identity-affirming resource centers, the absence of confidential mental health therapists within these facilities necessitates that staff report survivors to an equal opportunity and Title IX office (ST003). They also argued that they felt hesitant to ask for help since their respective college was very “male-dominated” (ST003). Similarly, another survivor noted that mandatory reporters are often “men, and that is hard as a female presenting individual…I felt like I was another file on their desk for them to get through” (ST033).

In addition, a survivor argued that having staff members in campus resources who “look like me” generates “a little bit of implicit trust” and added that for students with multiple marginalized identities, “I would imagine that for students who…do not see their identities reflected in those staff, that it is a lot more difficult to get to that level of trust” (ST029). Survivors who identified as Black/African/African American (8%), white (8%), Latinx (4%), biracial/multi-racial (4%), no race listed (4%), women or fem identifying (16%), male or masc identifying (4%), genderqueer (4%), non- binary (4%), queer (8%), bisexual (8%), first generation (8%), a person with disabilities (12%), and an immigrant (8%) indicated their frustrations with the lack of diversity. Survivors indicate that individuals sharing their identities in resource centers can help them feel safe and comfortable seeking assistance. This is especially true for women of color, LGBTQIA+ folks, first-generation students, immigrants, and persons with disabilities.

Lack of Support from Campus Resources

Lack of Awareness of Campus Resources

Various survivors indicated that they had little to no awareness of what campus resources existed, often leaving them unable to seek support. For example, a Latina and bisexual survivor said that at the time of their assault, they “didn’t know about all these resources” (ST011). Similarly, a first- generation female multiracial survivor wrote, “I guess I’m just not even familiar with the resources at all” (ST024). Others expanded on their confusion regarding available resources and the specific support they provide. A survivor elaborated, “I feel like generally, I had an awareness, but at the same time, there are so many different resources. You don’t know what exactly will fit your needs” (ST003). They also stated they had general knowledge about larger resource centers but “not the internal departments in them, which I think would be better to be more aware of. Because I did not know that the [survivor advocates] existed until the situation” (ST003). Someone else reported, “Because I felt like a lot of the information was really confusing…I felt like I just did not know who was reporting to who or like who I could talk to, or where I should go” (ST004). Most participants who felt unsupported by campus resources belonged to a racial or ethnic minority community, LGBTQIA+ community, a first-generation student, or were a person with disabilities, as they identified as white (5%), Latinx (11%), biracial/multiracial (5%), no race listed (5%), women or fem identifying (27%), genderqueer (5%), pansexual/polysexual (5%), queer (5%), bisexual (5%), first generation (11%), a person with disabilities (11%), and an immigrant (5%). Based on their experiences, it’s evident that campus resources need to implement diverse strategies to increase the availability and visibility of support resources for survivors with marginalized identities.

Lack of Follow-Up, Attentive Care, Trauma-Informed Practices, and Overly Long Processes

Approximately one-third of the survivors in this study expressed frustration with campus resources, citing issues such as lack of follow-up, unsatisfactory practices, inattentive care, and lengthy processes that exacerbated stress for survivors. For example, one who met with the Equal Opportunity and Title IX office described their experience as a “very time-consuming process,” requiring significant effort to push staff to take action against the perpetrator and remove him from campus (ST003). The survivor felt overwhelmed, and felt that their involvement felt “like my job for a semester.” With many of their concerns left unaddressed by on-campus resources, safety concerns arose since the perpetrator lived on the same floor in on-campus housing, prompting the survivor to seek refuge with a friend (ST003). However, after filing a report, the on-campus LGBT resource center and housing services collaborated to create a safety plan (ST003). A reluctance to turn to resources leaves survivors vulnerable to further harm from the perpetrator, as discussed by a first- generation student and woman of color who experienced fear and stalking on campus but refrained from seeking police assistance to help create a safety plan due to fear of dorm eviction (ST012).

Multiple survivors voiced frustrations regarding a lack of support from campus resources. One survivor who accessed campus survivor advocates felt unsupported after their initial contact, expressing that they “felt on my own again” as the advocate failed to follow up (ST004). Another participant described being handed “off to [a community police department]” by campus police without any follow-up despite having safety concerns (ST008). Similarly, someone else criticized the lack of follow-up from campus police, noting, “I put my report in, then looked back later and saw I’d gotten follow-up questions, but I hadn’t seen them in time before it was said the case was closed” (ST020). In addition, they argued that on-campus “therapy is hard to access, in that when I tried to access it, the phone line was probably blocked by my phone’s spam call blocker” (ST020). Another survivor felt unsupported by on-campus counseling center advocates due to perceived capacity issues: “It did not seem like they had enough capacity to follow up with me between the times I reached out to them for support” (ST029). Additionally, an African American, bisexual, nonbinary survivor with disabilities turned to a women’s resource center since they were “more female presenting at the time.” They ended up feeling like “just another number for them to get in, take a report, and move on,” arguing that they felt like they were “a short-term issue” to the women’s resource center (ST033).

Several survivors also raised concerns about the lack of trauma-informed care. For instance, I already shared the story of a survivor who recounted an incident where university police compelled her to recall the details of her assault while they sat in a public lobby (ST008). Another survivor experienced difficulty with their therapist at a women’s resource center due to the therapist’s “religious affiliation with [a very conservative church].” Consequently, they felt uncomfortable discussing how their faith deconstruction impacted their healing, attributing the lack of support to the therapists’ religious identity (ST029). In addition, a survivor of Hispanic descent initially felt supported by an on-campus therapist but later experienced “decompensation” (ST023).

Similarly, others highlighted the lack of follow-up from campus resources. One recounted feeling “ghosted” by their on-campus survivor advocate, expressing a desire for continued support but feeling unable to contact them after they “disappeared” (ST004). They also faced difficulties accessing a counseling center, encountering stringent requirements to receive crisis counseling; after two weeks, the survivor was not able to access services (ST004). Another praised their survivor advocate for their warmth and care, but “it also seemed like [the advocate] never had capacity,” leading to disengagement from “the things that I wanted to do because I did not have enough motivation or energy or capacity, and they were not there to hold my hand through it” (ST029). Additionally, they encountered wait times and frustrations at the university counseling center, where staff suggested seeking specialized services for gender-based violence without providing additional assistance in finding these resources (ST029). Survivors within this group identified as Black/African/African American (6%), white (12%), Latinx (6%), biracial or multi-racial (3%), no race listed (3%), women or fem identifying (19%), no gender identity listed (3%), genderqueer (6%), nonbinary (3%), pansexual/polysexual (3%), queer (9%), bisexual (3%), first generation (6%), a person with disabilities (15%), and an immigrant (3%). These experiences highlight survivors’ dissatisfaction with campus resources, which failed to support them adequately, engage in trauma- informed practices, provide follow-up care, or expedite processes.

Community Resources

Positive Experiences with Accessing Community Resources

A few survivors expressed satisfaction with community resources. This group hailed from diverse backgrounds: Black/African/African American (4%), white (14%), Latinx (9%), women or fem identifying (18%), nonbinary (4%), pansexual/polysexual (4%), queer (5%), bisexual (14%), first generation (5%), person with disabilities (18%), and an immigrant (5%). For example, a survivor identifying as a bisexual Latina found support through her employment by accessing therapy (ST011). Likewise, another Latinx survivor shared feeling comfortable talking to their therapist and acknowledged having health insurance and supportive loved ones (ST002). Another survivor, dissatisfied with phone-based support from a rape recovery center, found solace when accompanied by a supportive individual from the center during a hospital visit: “There was a person from the rape recovery center that was there with me, and they were super, super nice and helpful” (ST004). Another survivor received a recommendation from an academic advisor, subsequently praising the therapist’s quality and emphasizing the role of academic advisors in disseminating information about community resources (ST029).

Barriers to Accessing Community Resources

Economic Barriers

Multiple survivors encountered obstacles when accessing off-campus community resources. A Latina, queer, cisgender, and first-generation student cited difficulty accessing community resources due to their reliance on public transportation (ST005). In addition, a bisexual female-identifying survivor remarked on the challenges of realizing and addressing their experience, citing time and financial constraints as barriers to pursuing legal action (ST027). Survivors indicating economic barriers to accessing community resources identified as Latinx (15%), no race listed (15%), woman or fem identifying (14%), no gender identity listed (14%), queer (14%), and bisexual (14%), suggesting that it is primarily women of color and LGBTQIA+ folks who struggle to access community resources.

Fear of Filing a Police Report

Three survivors expressed their fear of police or having traumatic experiences with community police officers, with a majority in this category identifying as first-generation students. For example, a first-generation, multiracial female, recounted feeling victimized by police who aggressively sought information about the perpetrator, and they “ended up yelling at me (the victim in the situation) to get information about the perpetrator,” and “the police came to my home multiple times a day for weeks yelling and making threats for information I didn’t have. The response was more traumatizing than the actual strangling and assault” (ST024). A participant who identified as part of the LGBTQIA+ community and a white cisgender individual sought support from a rape recovery center but found their approach was “really intense.” They shared that the center “wanted [me]…to go to the hospital, and like go to the cops,” but because the survivor did not want to go to the hospital or talk with police officers, they felt that the center could not offer “very much support…so I kind of gave up on them” (ST004). Those who were fearful of community police officers identified as white (11%), biracial/multi-racial (11%), no race listed (11%), women or fem identifying (11%), no gender identity (11%), queer (11%), first-generation student (23%), and a person with disabilities (11%).

Lack of Support

Survivors sharing challenges in accessing community resources revealed common themes of lacking awareness of available support, feeling overwhelmed by too many options, and expressing doubts about community resources being able to adequately address their needs. A white, Mexican, female, and heterosexual participant stated, “I wasn’t sure of which off-campus resources there were” (ST010). Concerns about the lack of funding for community resources were also expressed, as highlighted by a white female, cisgender, heterosexual, survivor with chronic illness, who shared their concern about insufficient funding to pay for counseling (ST013). Another survivor felt unsupported after their community resource sessions ended: “Once my 6-month session ended, I heard nothing from them, and that did make me feel a little unsupported” (ST011). Similarly, a Mexican American, first-generation bisexual survivor who suffers from chronic illness expressed disappointment with the limited effectiveness of community resources (ST015). Another survivor found managing phone calls for legal assistance overwhelming, wishing on-campus advocates “had the capacity to do those with/for me” (ST029).

Many survivors mentioned that they felt like “another number” for staff working in community resource centers. For example, a bisexual and female-identifying survivor argued that they could not access community resources because they felt their “experience wasn’t ‘bad enough’ to spend resources that could be given to others” (ST017). Others argued that community resources could support crises but not long-term care, creating barriers for survivors seeking outside resources; as one survivor stated, “I did not always feel like there were resources when I was not actively in crisis, like several years out from an assault. So, I think that was probably the most difficult thing about accessing services [was] feeling like nobody ever had enough capacity” (ST029). Similarly, a white, female, Mexican, and heterosexual survivor mentioned that she “felt like one of many cases” (ST010). Those who expressed feeling unsupported identified as Black/African/African American (3%), white (14%), Latinx (8%), biracial/multiracial (6%), no race listed (3%), women or fem identifying (20%), genderqueer (3%), pansexual/polysexual (3%), queer (8%), bisexual (9%), first generation (9%), a person with disabilities (11%), and an immigrant (3%), which indicates a the widespread failure of community resources to address the needs of survivors with marginalized identities.

Thoughts about Mandatory Reporting Requirements

Positive Views of Mandatory Reporting

Twelve survivors, identifying as Black/African/African American (5%), white (9%), Latinx (4%), biracial/multi-racial (7%), no race listed (5%), women or fem identifying (20%), male or masc identifying (2%), no gender identity listed (2%), non-binary (2%), pansexual/polysexual (5%), queer (2%), bisexual (14%), first generation (7%), a person with disabilities (14%), and an immigrant (5%), indicated they felt that mandatory reporting requirements could be lifesaving. For example, a white, cis-gender, queer female with a disability argued that while they felt mandatory reporting was a “good idea,” it should be more thoroughly discussed with students before they disclose information that would have to be reported (ST006). A different survivor indicated, “I really like mandatory reporting; it can help victims reduce barriers in reporting and accessing resources” (ST008). Another survivor argued, “I think having someone who can tell you ‘this is wrong and we’re going to get justice for you’ makes all the difference” (ST011). Similarly, a survivor claimed that many survivors do not know what resources are out there, so “I feel like it’s a safe measure that helps protect students and connect students with proper resources” (ST016). Nearly one-third of survivors, with various identities felt that mandatory reporting was necessary to ensure their safety.

Anger, Fear, and Lack of Trust of Mandatory Reporters

Many survivors expressed dissatisfaction with federally-mandated mandatory reporting requirements, viewing them as insufficient in supporting survivors and instead causing anger and fear, which deters survivors from seeking help. They emphasized that these requirements create barriers, and lead many to avoid seeking help altogether to avoid a potential report to the equal opportunity and Title IX office. One survivor described how mandatory reporting erects a “barrier between people wanting to open up and tell their story” (ST003). Similarly, another pointed out that the assumptions surrounding mandatory reporting make individuals reluctant to seek support due to perceived risks to their privacy (ST029). In addition, a bisexual, disabled, and first-generation survivor stated, “I am very careful to avoid saying anything to a mandatory reporter that would lead to a report” (ST009). A South Asian international, heterosexual, and female student, found mandatory reporting intrusive and potentially retraumatizing, advocating for survivors to be empowered rather than coerced into reporting (ST014). Similarly, a multiracial, Japanese, first-generation female survivor described how the mandatory reporting process and the police response were more traumatic than the initial incident, eroding trust in community systems focused more on legal actions than personal safety (ST024).

Another described mandatory reporting as harmful to professors and staff, which can dissuade them “from engaging with students going through difficult circumstances because the faculty and staff worry that they will do something wrong and get in trouble or be forced to violate the student’s privacy by reporting a disclosure” (ST029). They elaborated that “it could be really traumatizing” for students, faculty, and staff to “navigate the mandatory reporting process, so I think it really freaks out a lot of faculty and staff” (ST029). Survivors indicating a lack of trust surrounding mandatory reporting identified as Black/African/African American (5%), white (11%), Latinx (3%), biracial/multi-racial (5%), no race listed (3%), women or fem identifying (17%), male or masc identifying (3%), no gender identity listed (5%), non-binary (3%), pansexual/polysexual (3%), queer (8%), bisexual (6%), first-generation (11%), a person with disabilities (14%), and an international student (3%).

Available on a Survivor’s Timeline

In addition to expressing their frustrations with mandatory reporting, many argued that they should have more say in whether their experience with gender-based violence gets reported to other authorities. This group identified as Black/African/African American (4%), white (17%), Latinx (7%), no race listed (4%), women or fem identifying (17%), no gender identity listed (4%), a part of the LGBTQIA+ community (4%), pansexual/polysexual (3%), queer (10%), bisexual (3%), first generation (10%), and a person with disabilities (17%). One pansexual white woman with chronic illness stated, “My experience with mandatory reporting was almost as traumatic as the assault itself, so I believe that after the danger has passed, reporting should be on the survivor’s timeline” (ST001). Another survivor with disabilities stated that mandatory reporting placed survivors in danger by potentially aggravating the abuser: “I think people should be able to get help without having to put themselves in further danger by filing a report” (ST009). Others discussed how the inflexibility of mandatory reporting creates barriers: “I feel like giving survivors the option to report with these people would probably be more helpful. I think, in my situation, I would have appreciated being able to talk to some people at these resource centers” without fearing that a mandatory reporter would give their case to the office of equal opportunity and Title IX (ST003).

Lack of Knowledge Surrounding Mandatory Reporting Requirements

Seven survivors, mainly people of color, international students, and members of the LGBTQIA+ community indicated having no knowledge about mandatory reporting requirements, which can lead survivors to turn to individuals they trust and who must report to other agencies. Survivors stated that they were “unaware what mandatory reporting is” (ST007), that they were “not aware of the mandatory reporting policy” (ST014), or that they were “not too familiar with it” (ST010). A nonbinary, African American, bisexual survivor with disabilities argued that they were “not aware of a mandatory policy and am not fully aware of what it fully entails. It does seem important and should be communicated more to students” (ST033). Students indicating a lack of knowledge of mandatory reporting requirements identified as Black/African/African American (5%), white (5%), Latinx (5%), biracial/multi-racial (5%), Asian/Asian American (10%), women or fem identifying (25%), no gender identity listed (5%), non-binary (3%), pansexual/polysexual (5%), queer (5%), bisexual (10%), a person with disabilities (10%), and an international student (5%).

Recommendations from Survivors with Marginalized Identities

Positive Experiences

Only 3 out of 33 respondents felt that campus resources adequately supported survivors and had no improvement recommendations. A white, Asian, pansexual, cisgender woman argued that they “had an extremely positive experience with all of the campus resources I connected with and would not change anything” (ST016). An African survivor argued that “everything is good” (ST022). And finally, a white, polysexual/sapphic, genderqueer individual shared that the “You might be causing harm if” series, promoted by an on-campus center for violence prevention, made them feel safer around cisgender men “on campus and I’d like to see other things like that” (ST020).

Better Training for Mandatory Reporters

When asked about recommendations to enhance campus resources, survivors emphasized the need for clearer guidelines on mandatory reporting requirements and increased training. A female- identifying bisexual survivor expressed dissatisfaction with their own mandatory reporting training, describing it as “inadequate and unclear” and highlighting areas that were not covered (ST017). Similarly, an Asian American, first-generation female student shared her experience with professors being uncertain about their role, which prompted her to seek “resources elsewhere” (ST019). Survivors also noted that mandatory reporters often lack clarity on reporting incidents. Based on this, they emphasized the necessity for further training, especially for managers dealing with disclosure and employee support (ST027). Another survivor pointed out that insufficient training on mandatory reporting dissuades some faculty and staff from engaging with students in need, stressing the importance of additional support and training (ST029). They suggested that current mandatory reporting requirements prioritize institutional liability over maximizing support for survivors of gender-based violence (ST029). Many survivors stressed the importance of providing comprehensive guidelines and training for mandatory reporters across all university levels to ensure adequate support for survivors.

More Diversity within Resources

Several survivors advocated for increased staffing in resource centers who work with survivors of gender-based violence as a way to enhance support provision. They also highlighted an absence of staff representing their identities as a barrier to accessing campus resources. For example, one expressed discomfort around police being tied to them “being more visually queer” and fearing unsupportive responses (ST020). A white female heterosexual survivor with chronic illness emphasized the necessity of female representation in the on-campus police force to ensure the serious consideration of survivors’ concerns, stating that “we need more cops to take women seriously” (ST013). Similarly, a Latino, male, first-generation survivor highlighted the misconception that men, especially Latinos, cannot be victims of gender violence, emphasizing the need for recognition and support for male survivors (ST021).

Many survivors emphasized the importance of diverse mental health therapists and staff at resource centers to encouraging disclosure by fostering comfort. A first-generation, Latina, queer, cis- gender, participant stressed the need for QTPOC representation on campus (ST005). Similarly, a bisexual first-generation student advocated for diverse representation among campus-based resource providers to enhance inclusivity and safety (ST031). They underscored the value of offering specific identity-based locations to eliminate the need for survivors to educate staff on their identities, thus removing barriers to seeking treatment (ST031). A Black and non-binary survivor called for more “female or queer” mandatory reporters to create a more comfortable environment when disclosing their experience (ST033). Highlighting the importance of identity-based student organizations, one survivor mentioned that their presence and discussions about resources could encourage others to seek support due to trust established through forming community with these organizations (ST019). Moreover, culturally competent mental health counselors were deemed crucial, with a survivor stressing the need for “a wide variety of culturally appropriate counselors” (ST002). Another survivor advocated for hiring staff that reflect student identities, emphasizing the need for additional funding to support positions catering to the populations they serve (ST029). Survivors’ experiences and recommendations underscore the university’s imperative to allocate funding for positions aiding gender-based violence survivors while ensuring counselors mirror student identities.

More Awareness of Available Resources

Eight survivors, predominantly individuals of color, first-generation students, or from the LGBTQIA+ community stressed the importance of campus resources finding effective ways to promote their services for survivors of gender-based violence. One survivor emphasized the need to increase “awareness,” so survivors understand “that people are here to help, even if the incident wasn’t on campus” (ST011). Another survivor, while navigating the process of seeking accommodations with various campus departments, described the emotional toll of repeatedly recounting their trauma and the challenges of understanding the roles and communication channels between departments. They highlighted the difficulties in seeking academic and emotional support after the process, mainly due to ADHD and PTSD. Additionally, they advocated for discreet signage or reminders, like QR codes or business cards in bathroom stalls, to lessen feelings of shame or anxiety when seeking help. They expressed discomfort approaching the women’s resource center or survivor advocate tables during large events due to privacy concerns, stating, “I didn’t want people to look at me and know what happened to me” (ST012). A survivor emphasized needing “more awareness of resources and refreshers” (ST014). Additionally, a woman of color highlighted the necessity “for more visibility of all the resources,” expressing regret over not being aware of them earlier (ST015). A first-generation multiracial female admitted being “not even familiar with the resources at all” and felt disconnected from them in daily life (ST024). Similarly, a white, pansexual woman with chronic illness suggested making counseling resources more widely known (ST001). Someone else proposed providing students with pamphlets during New Student Orientation to highlight available resources (ST003). These insights underscore the importance of incorporating campus resource centers’ suggestions into strategies for enhancing students’ awareness of available resources. More Support for Secondary Trauma SurvivorsAn immigrant woman advocated for campus resources to provide support for secondary trauma victims. She highlighted that while most resources focus on supporting survivors, those who are “trying to have compassion for the [survivor] and listening to what [a survivor] went through” are left without help (ST002). She emphasized that listening to survivors’ trauma can cause “some trauma” and mental health issues (ST002). Stressing the importance of support for those experiencing secondary trauma, she stated, “I would be happy to see that other people also feel comfortable coming and asking for support, even if they were not the ones directly impacted” by gender-based violence (ST002).

More Communication between Departments

Two survivors seeking accommodations expressed frustration with lengthy processes and poor interdepartmental communication, which resulted in them having to repeatedly relive their trauma while navigating how much information to disclose. An African American, heterosexual, cis- gender, first-generation student argued that “academic administration needs to communicate better with survivor advocating departments,” suggesting that “[administrative] offices should give a summary of the matters they are handling for the student,” without “retelling the [survivors’] story,” as a way “to keep survivor-needs centered and organized” (ST012). A white, queer, disabled woman mentioned needing academic accommodations and, therefore, “had to accept some loss of privacy in order to get the academic accommodations I need” (ST029). She stated that “it feels really embarrassing to reach out and ask for [academic accommodations], and to know that my name is going down in a database, or in a report where way too many staff members could access it” (ST029).

More Funding for Resources

One survivor urged the university to allocate additional funding specifically to resources addressing gender-based violence with the goal of supporting survivors and mental health experts more fully. Describing themselves as a “white queer disabled woman,” the survivor emphasized the urgent need to “fund more therapist and advocate positions.” When “compared to other PAC-12 schools, the clinician-to-student ratio is pretty abysmal,” and she noted that “waitlists to see a therapist or advocate should not be multiple weeks long. The therapists and advocates are underutilized, overwhelmed, understaffed, and under-supported by the university.” They stress that therapists “continue to burn out and leave unless the university puts its money where its mouth is” by funding more positions. Furthermore, she emphasized the importance of recruiting “more victim survivor advocates from the populations that they are serving,” such as diverse individuals, to ensure support for survivors with marginalized identities (ST029).

Implications of Findings

The findings from survivor’s stories reveal insufficient support from both campus and community resources for survivors with marginalized identities as well as those experiencing secondary trauma. Drawing from survivors’ stories and experiences with campus resources, it is evident that the university should abandon its uniform approach to addressing gender-based violence. Instead, it must prioritize understanding the intersectionality of identities and acknowledge how historical legacies such as slavery, forced displacement, dehumanization, settler colonialism, xenophobia, and genocide impact survivors’ access to on-campus resources.

In the research findings, survivors’ narratives were pivotal and their recommendations, rooted in their lived experiences, must guide the development of improved institutional practices that acknowledge and dismantle barriers faced by survivors of color, LGBTQIA+ folks, immigrants, first-generation students, international students, and people with disabilities. Survivors with economic and safety concerns should prompt the university to reconsider its policies for better-accommodating survivors’ needs. For instance, several women of color and LGBTQIA+ folks expressed significant distrust of campus police, causing them to endure stalking due to the lack of safety planning options. Survivors should have access to safety planning through alternative campus entities like survivor advocates, who must widely publicize their role in addressing safety concerns. This ensures that survivors do not feel compelled to seek safety assistance from offices like the equal opportunity and Title IX office or the police, which are distrusted and feared by LGBTQIA+ folks, communities of color, and immigrant students. One survivor suggested that commuter services should offer exemptions, particularly for survivors with safety concerns, allowing them to park closer to certain buildings for enhanced safety. Many survivors fear retribution for reporting perpetrators, and several are frustrated with the university’s prolonged processes for removing perpetrators from campus or student housing. Additionally, campus offices responsible for accommodations should collaborate more closely with mental health counselors to prioritize survivors’ needs and minimize the need for students to recount their trauma repeatedly. Clear guidelines should be established regarding the amount of information survivors must disclose to respective offices, ensuring their privacy and comfort.

Moreover, a significant number of survivors, particularly those from communities of color, first-generation, immigrant, or LGBTQIA+ communities, expressed feelings of being “underserving of help” or that their “incidents were not big enough” to seek assistance. To address this, the university should prioritize the development of culturally competent sexual education courses. These courses can provide survivors with a better understanding of pervasive rape myths and the enduring impacts of dehumanization, which often affect survivors with marginalized identities and may contribute to feelings of “unworthiness.”

Additionally, survivors’ reluctance to report abusers highlights a lack of trust in the police and other campus systems’ ability to provide necessary support, thereby increasing the risk of harm. LGBTQIA+ survivors, people with disabilities, immigrants, and those from communities of color particularly noted campus police officers’ apathy toward their safety needs and lack of trauma- informed practices. To address these concerns, the university should focus on recruiting a more diverse workforce and implementing stricter guidelines and training on culturally competent and trauma-informed practices for campus police officers. This ensures that if survivors with marginalized identities choose to engage with campus police, their safety needs and concerns are effectively addressed. Furthermore, the failure of campus police to protect survivors with marginalized identities perpetuates the longstanding fear of state actors, which has persisted for centuries.

Resource centers and survivor support services should enhance awareness of federally mandated mandatory reporting requirements, particularly among students with marginalized identities who have indicated a lack of understanding regarding mandatory reporting. In response to survivors’ recommendations, the university needs to offer clearer information about who mandatory reporters are, considering some survivors’ negative experiences with police or mandatory reporters compared to their assaults. Furthermore, the university should provide comprehensive training for faculty and staff to better assist survivors through the complex and stressful reporting processes to other agencies.

Given survivors expressed a preference for more flexible mandatory reporting requirements, confidential support services such as the on-campus survivor advocates and women’s resource center should actively promote their ability to support while maintaining confidentiality. Additionally, recognizing students’ comfort with individuals within diverse resource centers, the university should allocate additional funding to deploy confidential and culturally competent mental health counselors within various resource centers. This initiative aims to create a safe space for survivors to seek on-campus support from resources tailored to students with marginalized identities without the risk of being reported to other agencies that could potentially exacerbate harm.

Survivors also noted challenges in accessing or receiving support from community resources, underscoring the need for increased funding from the state legislature for survivor support services to aid student survivors effectively. Additionally, considering survivors reported lack of awareness of available community resources, campus support services should strive to equip survivors with the necessary tools and information to access off-campus resources.

Furthermore, many survivors expressed a lack of knowledge or awareness regarding campus resources or dissatisfaction with the support provided. To address this, the university, especially survivor support services, should enhance information dissemination about available resources and allocate more funding to ensure efficient access to address survivors’ needs. Many survivors felt they were treated as “just another number” by campus resources, highlighting the necessity for increased funding to ensure comfort and support for survivors as well as to prevent burnout among on-campus mental health counselors. Collaborating closely with trusted resources such as identity-affiliated resource centers and student groups can equip students with the tools to promote available resources. Similarly, survivor support services should employ diverse strategies, such as collaborating with New Student Orientation to distribute pamphlets or discreetly placing information around campus, as suggested by one survivor, such as in bathroom stalls, to enhance awareness of available support services.

University leaders, particularly those overseeing survivor support centers, should prioritize hiring diverse, trauma-informed, and culturally competent counselors. This approach ensures survivors can access services without having to explain their lived experiences or educate counselors about intersecting identities. Moreover, the university should allocate sufficient funding to these centers to hire counselors who reflect the identities of the student body, fostering a sense of safety and support.