College of Humanities

48 An Analysis of Vowel Reduction in Bolognese

Brandon Osgan

Faculty Mentors: Edward Rubin and Aaron Kaplan (Linguistics, University of Utah)

This study presents an analysis of vowel reduction in Bolognese. The vowels of Bolognese’s vowel inventory reduce to be [+high] and [+ATR], becoming either [i] for front vowels or [u] for back ones. The context in which this occurs is known as a derived environment, in which a vowel that can be stressed in another form of the respective word but is no longer stressed in the current form of the word is targeted for vowel reduction. In contrast, vowels that are never stressed in any form of the respective word are not targets for vowel reduction. The ranking of the necessary constraints to derive the correct surface form of the word explains how this observed reduction to the corresponding high-tense counterpart occurs. There is another observed vowel reduction pattern in Bolognese which only targets the vowels [ɛː], [aː], and [a] in which we see these vowels reduce either to [a] or simply to nothing. To account for this second reduction pattern, we adopt two separate phonologies each with their own ranking of the constraints. In comparing Bolognese words that demonstrate the second pattern to their Italian cognates there appears to be a correlation, where the vowels in Bolognese reduce, and in Italian an adjacent consonant to the target vowel will be lengthened. This suggests that there may be historical evidence in Bolognese for favoring the second reduction pattern over the first, though for modern speakers this choice seems to be arbitrary.

Introduction

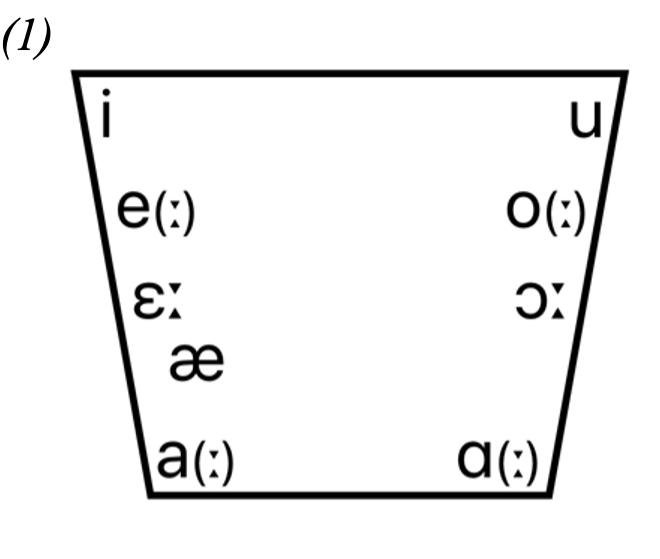

This study seeks to provide a comprehensive analysis of the phenomenon of vowel reduction in Bolognese, situated within the broader context of Romance linguistics. Bolognese is a Gallo-Italic language, part of the larger Romance language family, primarily spoken in Bologna, a city in Italy’s Emilia-Romagna region. Bolognese is one of the many endangered Emilian languages, with only between 10k to 1M native language (L1) users left of all Emilian languages spoken (Eberhard, Simons, & Fennig, 2024). Linguistic work is increasingly being conducted in this language, notably with Canepari & Vitali (1995), and Vitali (2008) who investigate the acoustics and phonetics of Bolognese vowels and consonants. Much of these works are contained in an online database (Compagnia del Bolognese, 1999). This study documents how vowel reduction occurs in Bolognese, wherein vowels (1) reduce to be [+high] and [+ATR], becoming either [i] for front vowels or [u] for back ones. There is a second observed reduction pattern where we see the reduction of specifically the vowels [ɛː], [aː], and [a] reduces either to [a] or simply to nothing. To account for this second reduction pattern, we adopt two separate phonologies. Each of Bolognese’s reduction patterns is attested by Crosswhite (2001), providing further evidence supporting her predictions regarding contrast-enhancing and prominence-aligning vowel reduction patterns.

(1)

Prominence Reduction

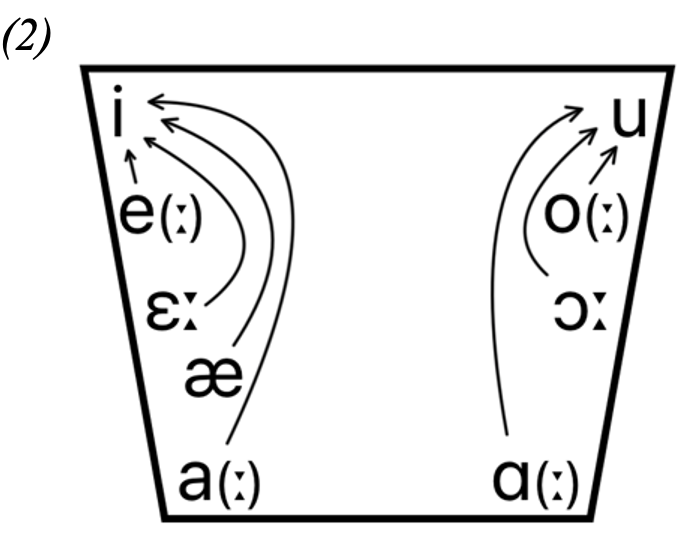

This study looks at the phenomenon of vowel reduction through the framework of Optimality Theory. In Bolognese, non-peripheral vowels are deemed undesirable in unstressed positions and are subsequently targeted for vowel reduction. (2) illustrates the movement of these non-peripheral vowels during vowel reduction.

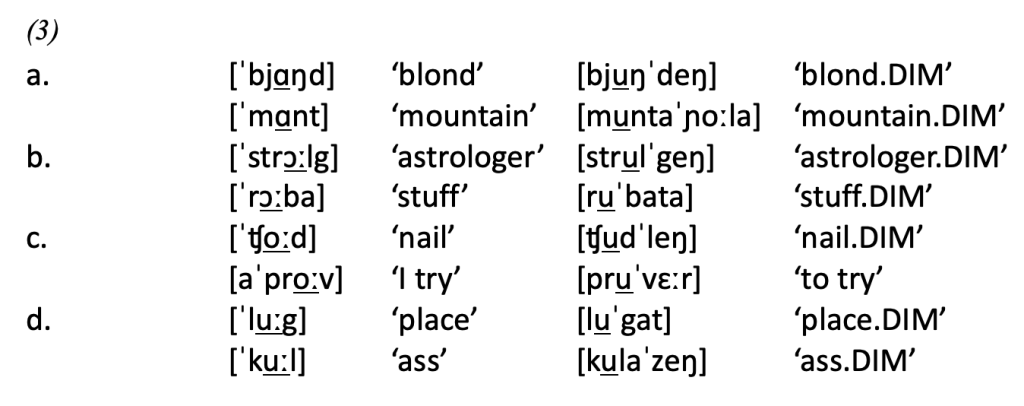

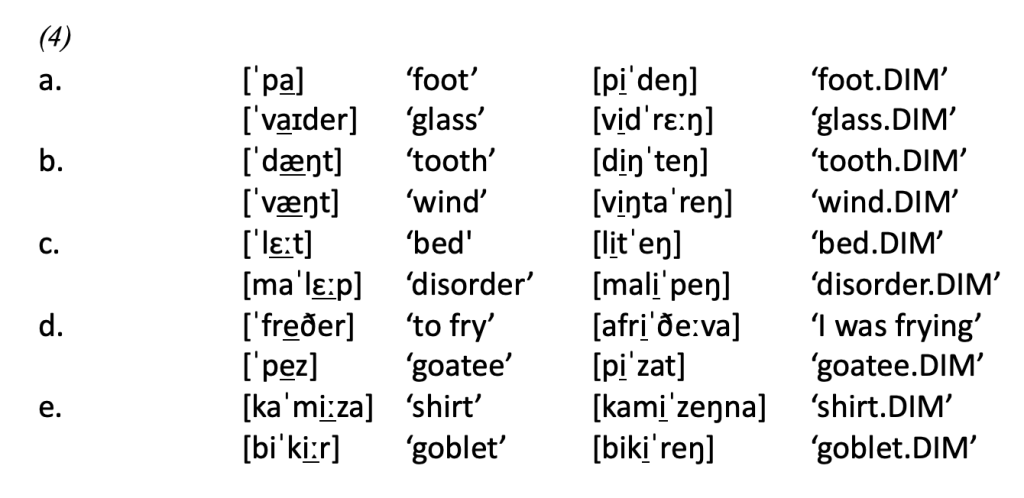

In the unstressed position, we find that back vowels reduce to the [+high, +round, +ATR] vowel [u], as in (3). We can see this in (3a) with the word ‘blond.’ In this word, we have an underlying [+low, +back] [ɑ]. When the diminutive suffix [eŋ] is added to the word, stress shifts off the [ɑ]. Because the vowel is no longer stressed it becomes a target for vowel reduction. In the same context, we find that front vowels reduce to the [+high, -round, +ATR] vowel [i], as in (4). We can see this in (4a) with the word ‘foot.’ In this word, we have an underlying [+low, -back] [a]. As we saw before, when the diminutive suffix [eŋ] is added to the word, stress shifts off the [a]. Because the vowel is no longer stressed it becomes a target for vowel reduction.

Regardless of whether reduction occurs, vowels in an unstressed position in Bolognese will always be short (i.e. an unstressed syllable may only contain one mora (μ) in the nucleus) per the weight- to-stress principle. In (4e), we see that though the target vowel [iː] is already peripheral and thus may not appear to change in quality during vowel reduction, it does change in duration (reducing from 2 moras to only 1 mora contained in the nucleus) due to its new unstressed position.

Likewise, in (4a), the target vowel contains a diphthong and must be shortened during reduction. This type of vowel reduction pattern found in Bolognese has been predicted (Crosswhite, 2001) and exemplifies the phenomenon of prominence reduction. Two types of vowel reduction are introduced by Crosswhite (2001): contrast enhancement and prominence reduction. Contrast enhancement seeks to eliminate all non-peripheral vowels in unstressed positions, while prominence reduction seeks to avoid particularly salient vowels in unstressed positions (Crosswhite, 2001).

A Second Pattern

In Bolognese, while the vowel reduction pattern discussed above is the primary pattern used in the language, it is not the only one. There is a second vowel reduction pattern in which only the vowels [ɛː], [aː], and [a] display different means for reduction. In contrast, all other vowels maintain the same pattern as stated above. In this second pattern, the vowels [ɛː] and [a] delete when in an unstressed position, rather than reducing to [i] or [u] when in this position.

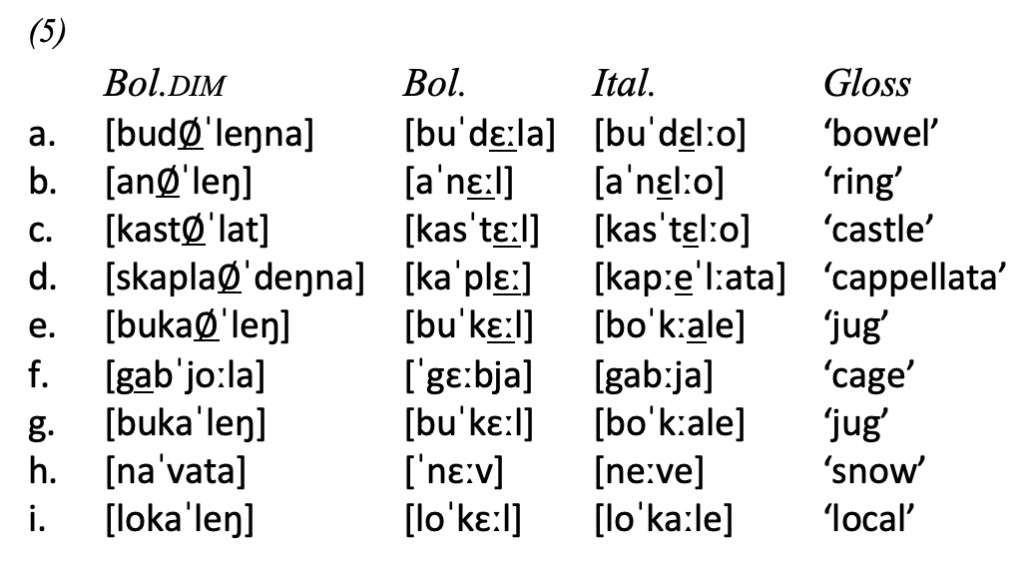

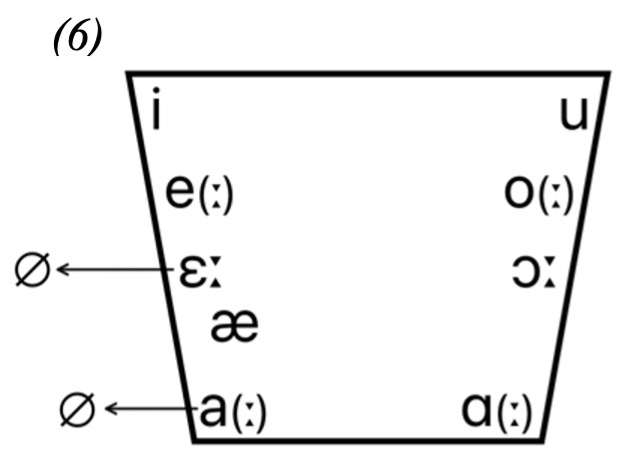

(6) illustrates the movement of these vowels during vowel reduction. We can see this second pattern of vowel reduction in (5a) with the word ‘bowel.’ In this word, we have an underlying [ɛː]. When the diminutive suffix [eŋna] is added to the word, stress shifts off the [ɛː]. Because the vowel is no longer stressed it becomes a target for vowel reduction, resulting in its deletion. However, if an ill-formed complex onset or coda were to result from this deletion, the vowel instead reduces to the short vowel [a] as seen in (5f) and (5g), though this reduction to [a] does not appear to be exclusive to the context of preventing an ill-formed complex onset or coda. Both the pattern in (2) and here in (6) exemplify the second type of vowel reduction, prominence reduction. In the first pattern, vowels reduce to [i] or [u] to avoid more salient vowels in unstressed positions, while vowels delete in the second reduction pattern to avoid these particularly salient vowels in unstressed positions. (6)

(6) illustrates the movement of these vowels during vowel reduction. We can see this second pattern of vowel reduction in (5a) with the word ‘bowel.’ In this word, we have an underlying [ɛː]. When the diminutive suffix [eŋna] is added to the word, stress shifts off the [ɛː]. Because the vowel is no longer stressed it becomes a target for vowel reduction, resulting in its deletion. However, if an ill-formed complex onset or coda were to result from this deletion, the vowel instead reduces to the short vowel [a] as seen in (5f) and (5g), though this reduction to [a] does not appear to be exclusive to the context of preventing an ill-formed complex onset or coda. Both the pattern in (2) and here in (6) exemplify the second type of vowel reduction, prominence reduction. In the first pattern, vowels reduce to [i] or [u] to avoid more salient vowels in unstressed positions, while vowels delete in the second reduction pattern to avoid these particularly salient vowels in unstressed positions. (6)

To account for both vowel reduction patterns in our analysis, we implement cophonologies. It does not seem possible to predict which reduction pattern any instances of these two vowels will exhibit, though Italian cognate contextual evidence points to a historical change from Latin may be the determining factor (Vitali, 2008). For vowels in which the deletion reduction pattern is used, we find that in Italian cognates the vowel in question systematically appears next to long consonants, particularly often long [l]. With both Italian and Bolognese belonging to the Romance language family, this suggests that historical factors may be able to explain the criterion that determines which reduction pattern will apply. Vitali (2008) may be able to shed some light on what a shared historical form might be, though as of the writing of this analysis, it remains unclear.

Derived Environment Effect

To analyze vowel reduction, we must first identify the context in which vowels may reduce. Bolognese exhibits what is known as a derived environment effect, where vowel reduction occurs in an unstressed syllable, but only when this context has been created by something responsible for shifting stress off the vowel that reduces, such as affixation or verb conjugation. As an example of this effect, take the word [maˈlɛːp] ‘disorder’ and its diminutive form [maliˈpeŋ]. The [a] vowel in this word never reduces due to it always being unstressed, while the [ɛː] sound does reduce only after the affixation of the diminutive ending [eŋ] shifts stress off the vowel, creating our derived environment effect.

OT Constraints

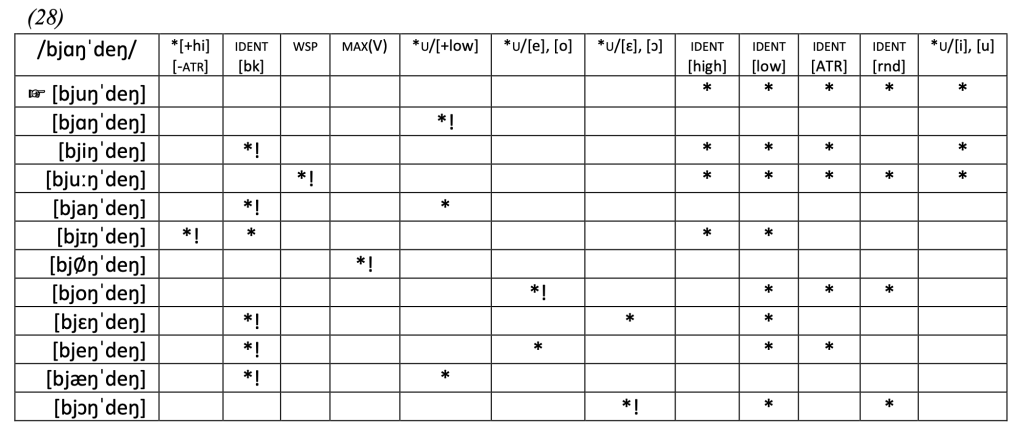

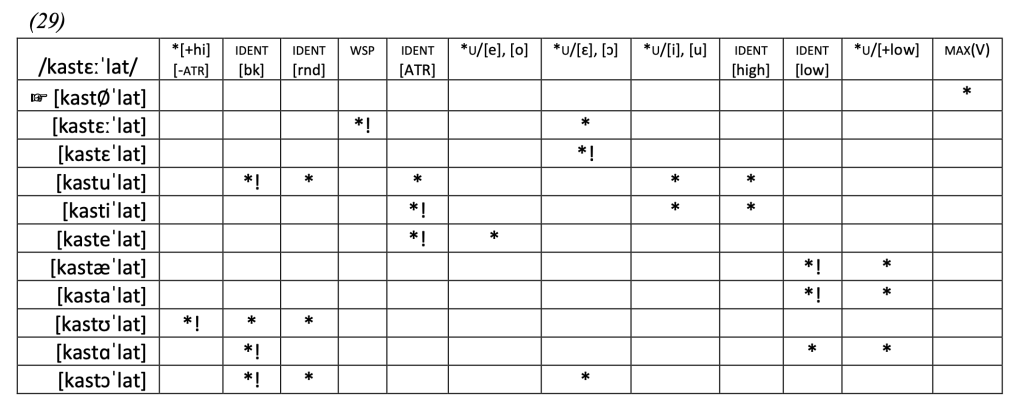

To derive the surface forms of Bolognese words that have undergone vowel reduction, we must give careful attention to the rankings of 10 constraints. Due to the co-phonological grammar of Bolognese, we are unable to account for both vowel reduction patterns under one hierarchy of constraints. In consequence, each grammar has its own corresponding hierarchy. We will first analyze the contrast-enhancing vowel reduction pattern (28) followed by the prominence-reducing pattern (29).

*Unstressed

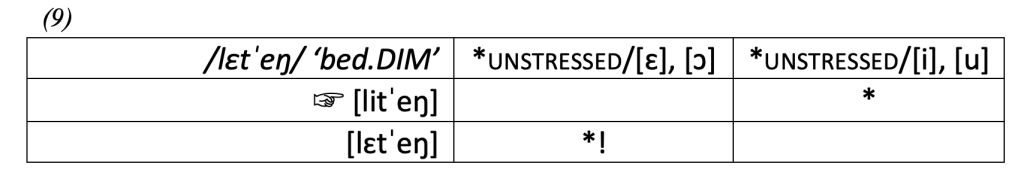

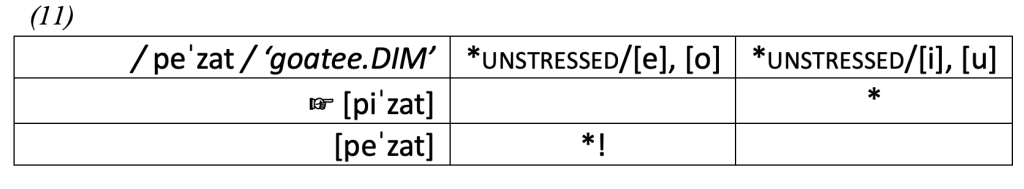

The first set of constraints we need all do similar things, though target different vowels. In this analysis, we adopt the following constraints from Crosswhite (2001): *UNSTRESSED/[+low], and three constraints of the form *UNSTRESSED/[X], [Y], where X = a front vowel and Y = a back vowel with the same height specification as X, those constraints being *UNSTRESSED/[e], [o],

*UNSTRESSED/[ɛ], [ɔ], and *UNSTRESSED/[i], [u]. Each constraint states that in an unstressed position of a word, we assign a violation mark when a particular vowel or vowel feature is present. For example, in (11) with the constraint *UNSTRESSED/[e], [o], we specifically target the vowels [e] and [o]. If we find one of these two vowels in an unstressed position, we assign a violation.

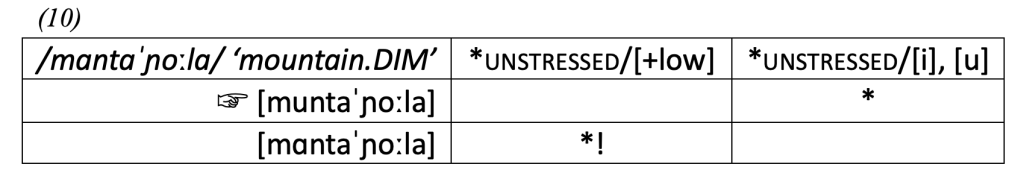

Similarly, in (10) with the constraint *UNSTRESSED/[+low], we target specifically vowels that have the feature [+low]. If we find a vowel with this feature in an unstressed position, we assign a violation mark.

(7) *UNSTRESSED/[X], [Y]: assign one violation mark for each unstressed [X] or [Y].

(8) *UNSTRESSED/[+low]: assign one violation mark for each unstressed [+low] vowel.

The following tableaux show how these constraints are ranked amongst one another. These rankings presented are part of the larger hierarchy of constraints needed to achieve vowel reduction in Bolognese. Additionally, violations are shown in all tableaux only for vowels that are targets for reduction.

(9)

(10)

(10)

(11)

(11)

Max(V)

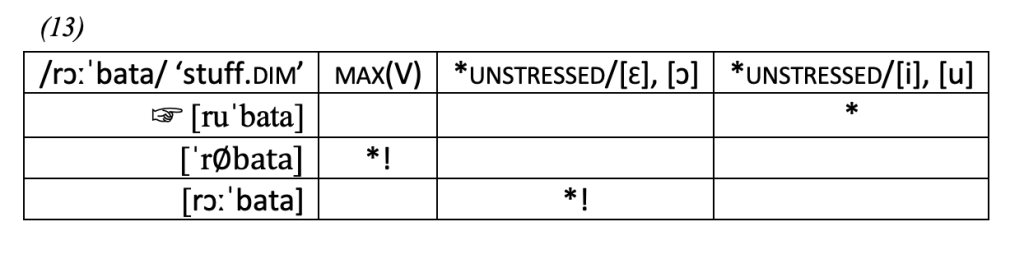

Another constraint necessary for Bolognese’s vowel reduction is MAX(V). This constraint states that vowels that appear in the input of a word must also appear in the output. If a vowel is deleted, we assign a violation mark. Vowels that undergo quality changes do not violate this constraint.

Additionally, this constraint prevents Bolognese from simply deleting vowels to comply with the

*UNSTRESSED constraints.

(12) MAX(V): assign one violation mark for each vowel deleted.

(13)

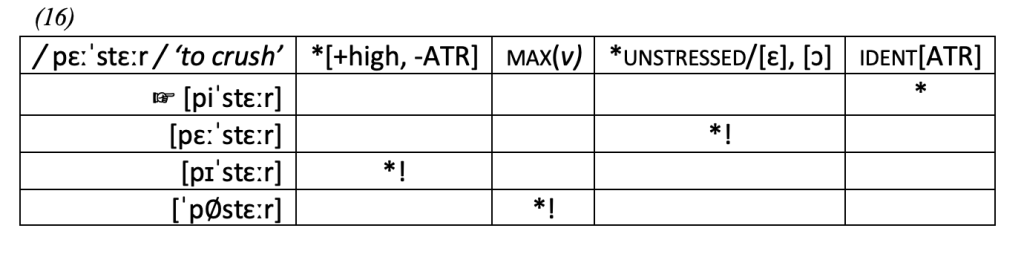

Advanced Tongue Root

Another set of constraints necessary for Bolognese’s vowel reduction are *[+high, -ATR] and IDENT[ATR]. The first constraint states that if a vowel is specified as [+high] while also being specified as [-ATR] it is assigned a violation mark. This prevents peripheral lax ([-ATR]) vowels from surfacing. The second constraint states that if the specification of the feature [ATR] from the underlying vowel and the surface vowel are not identical, we assign a violation mark. These constraints can conflict with one another, however, *[+high, -ATR] outranks IDENT[ATR] in the hierarchy. Consequently, a [+high, +ATR] vowel will always be more favored regardless of whether it violates IDENT[ATR].

(14) *[+high, -ATR]: assign one violation mark for each [+high, -ATR] vowel.

(15) IDENT/[ATR]: assign one violation mark if [ATR] is not identical in UR and SR.

The following tableau shows how these constraints are ranked amongst one another. These rankings presented are part of the larger hierarchy of constraints needed to achieve vowel reduction in Bolognese.

(16)

Ident

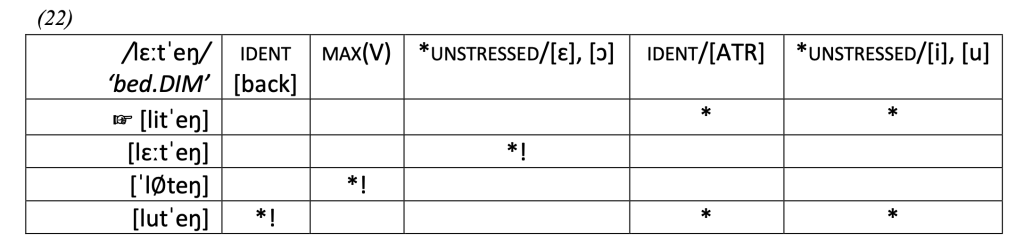

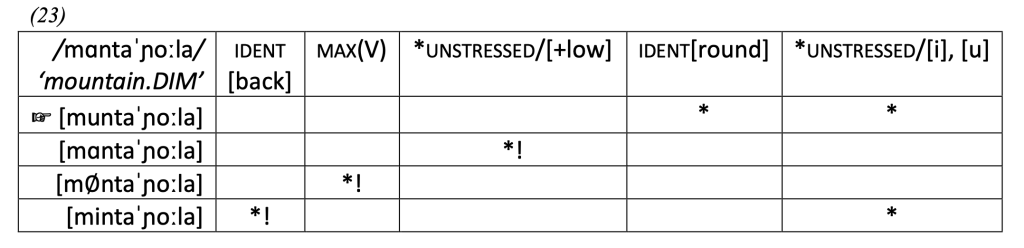

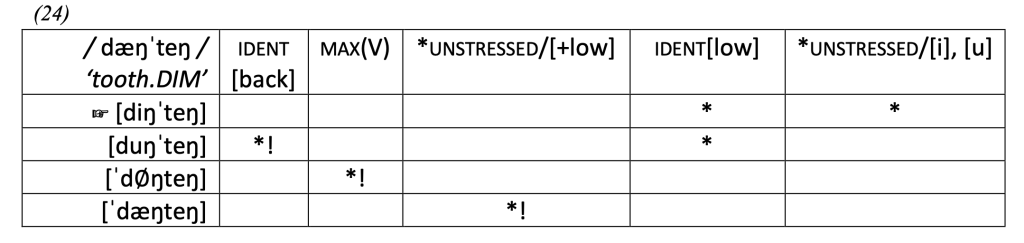

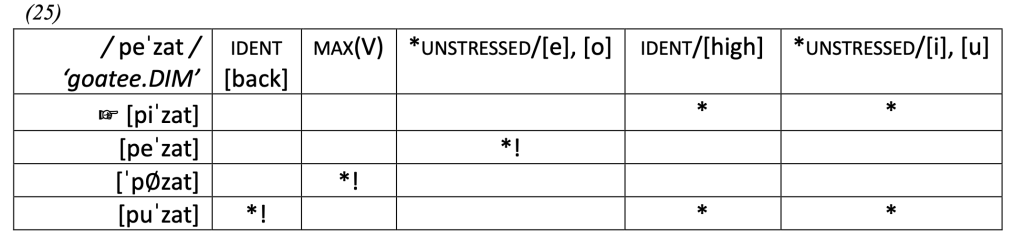

The second set of constraints we need are all faithfulness constraints for specific features. In this analysis, we adopt the constraints IDENT[back] and IDENT[round]. Both constraints state that if the feature specification from the underlying vowel and the surface vowel for a particular feature are not identical, we assign a violation mark. For example, in (24) with the constraint IDENT[back], we want the specification for the feature [back] to be identical in the surface vowel as it is in the underlying vowel; the specification being [-back]. If we find that the specification for the feature is not identical, we assign a violation.

(17) IDENT/[ATR]: assign one violation mark if [ATR] is not identical in UR and SR.

(18) IDENT/[round]: assign one violation mark if [round] is not identical in UR and SR.

(19) IDENT/[back]: assign one violation mark if [back] is not identical in UR and SR.

(20) IDENT/[low]: assign one violation mark if [low] is not identical in UR and SR.

(21) IDENT/[high]: assign one violation mark if [high] is not identical in UR and SR. The following tableaux show how the IDENT constraints are ranked with respect to the

*UNSTRESSED constraints. These rankings presented are part of the larger hierarchy of constraints needed to achieve vowel reduction in Bolognese.

(22)

(23)

(23)

(24)

(24)

(25)

(25)

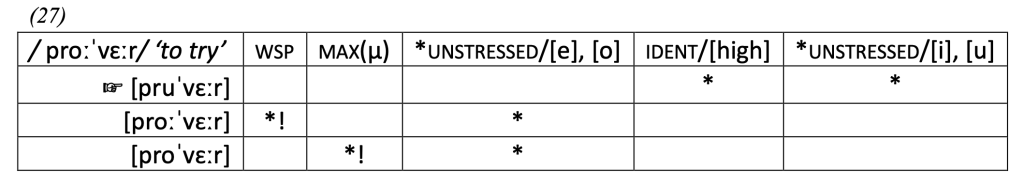

Weight to Stress Principle

The final constraint necessary for Bolognese’s vowel reduction is the weight-to-stress principle (WSP). This constraint states that we assign a violation mark if we find a heavy syllable in an unstressed position. The primary targets for this constraint are unstressed syllables that have two moras in their nucleus. Whether the vowel is long or part of a diphthong is irrelevant.

(26) WSP: assign one violation mark for each long vowel contained in a heavy syllable.

The following tableau shows how this constraint is ranked with respect to the *UNSTRESSED and IDENT constraints. The constraint MAX(μ) is used to show how violations are assigned by the shortening of a vowel but will not be included in other tableaux. These rankings presented are part of the larger hierarchy of constraints needed to achieve vowel reduction in Bolognese.

In (28) we see how each of the constraints needed relate to one another to form a hierarchy, which when followed during reduction will achieve the first vowel reduction pattern in Bolognese. *U will be used in place of *UNSTRESSED in tableaux (28) and (29). As previously discussed, Bolognese exemplifies two distinct vowel reduction patterns, the second of which only targets the vowels [ɛː], [aː], and [a] which reduce either to [a] or simply to nothing. To achieve this second vowel reduction pattern, a new hierarchy of the constraints is needed.

As previously discussed, Bolognese exemplifies two distinct vowel reduction patterns, the second of which only targets the vowels [ɛː], [aː], and [a] which reduce either to [a] or simply to nothing. To achieve this second vowel reduction pattern, a new hierarchy of the constraints is needed.

Because the second vowel reduction pattern involves deletion, MAX(V) must be ranked significantly lower within the hierarchy. Additionally, the constraint *UNSTRESSED/[+low] must be ranked lower to allow for a reduction to [a], unlike the first pattern where it is ranked much higher to allow for a reduction to [i] or [u]. While (28) reflects the first vowel reduction pattern of Bolognese, (29) reflects the hierarchy needed to achieve the second pattern. The primary rankings of constraints that distinguish these two patterns are IDENT[round], WSP, MAX(V), IDENT[ATR], and *UNSTRESSED[+low].

Further Discussion

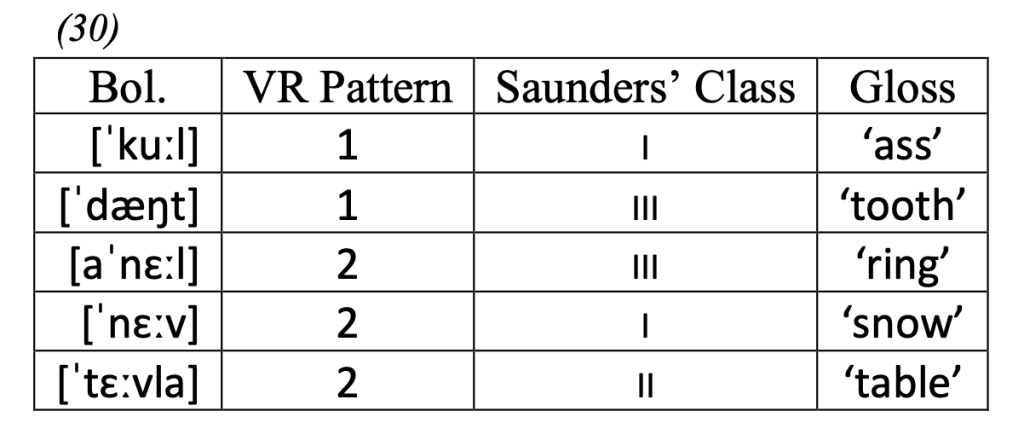

As it stands now, it is unclear as to what the criterion is that determines how words are categorized into one vowel reduction pattern over the other. Saunders (1984) investigates the morphology of Bolognese and in doing so proposes a class system for words that determines how words metaphonize. It was hypothesized that there may be a correlation between the two vowel reduction patterns and Saunders’ class system, though as seen in (30) a correlation is not apparent.

Closer inspection between the vowel reduction patterns and Saunders’ class system may be needed, though as it currently stands there is yet to be evidence found that shows support for this. What does appear to be certain regarding Bolognese’s vowel reduction is that it exemplifies two distinct patterns, one of contrast enhancement and one of prominence reduction. In addition to this, there is an observed derived environment effect, where vowel reduction occurs in an unstressed syllable, but only when this context has been created by something responsible for shifting stress off the vowel that reduces.

An intriguing discovery was made in comparing Bolognese words that demonstrate the second vowel reduction pattern with their cognates in standard Italian. What was found is that where in Bolognese we see the target vowel reduce following the second reduction pattern, in standard Italian a consonant adjacent to the target vowel is often lengthened (5). This suggests that perhaps there is historical evidence that can explain this categorization, where in Bolognese’s development the adoption of a second vowel reduction pattern was necessary, but in standard Italian the lengthening of an adjacent consonant was necessary. It is unclear as to what this historical fact may be, though it is certainly associated with Bolognese’s development from vulgar Latin. For modern speakers of the language, the categorization of a word to display one vowel reduction pattern over the other appears arbitrary, though a wug-test-like experiment may reveal whether there are developing adaptions for patterns of categorization or if it remains truly arbitrary.

Conclusion

This study has shed light on the intricate phonological intricacies of Bolognese, contextualized within the broader framework of Romance linguistics. Through the implication of Optimality Theory, we have examined the phenomena of contrast enhancement in Bolognese and found evidence for the necessity of a co-phonological analysis of the vowel reduction pattern. The careful analysis of Bolognese’s derived environment context has provided evidence of the lexically encoded nature of vowel reduction. Moreover, our research has underscored the historical depth of Bolognese’s development, as evidenced by intriguing correlations with Italian cognates in relation to the second vowel reduction pattern.

Acknowledgments

The data in this paper was primarily collected from the second edition of Dizionario Bolognese- Italiano (Lepri & Vitali 2009), with IPA transcriptions reviewed by Edward Rubin. I thank Edward Rubin and Aaron Kaplan for providing me with the opportunity to conduct this research under their guidance and supervision, and for providing feedback on this work. I thank Edward Rubin, Aaron Kaplan, and Tanner Jones for their extensive discussion of the work. I thank the University of Utah Student Conference in Linguistics, the University of Utah Undergraduate Research Symposium, and the University of Utah College of Humanities Research Symposium for providing me with the opportunity to present this work. I thank the University of Utah Office of Undergraduate Research for funding a portion of this work.

Works Cited

Canepari, L., & Vitali, D. (1995). Pronuncia e Grafia del Bolognese. Rivista Italiana di Dialettologia, 119-164.

Compagnia del Bolognese. (1999, September 2). Retrieved from Al Sît Bulgnais – Il Sito Bolognese: https://www.bulgnais.com

Crosswhite, K. (2001). Vowel Reduction in Optimality Theory. In L. Horn, Outstanding Dissertations in Linguistics. London: Routledge.

Eberhard, D. M., Simons, G. F., & Fennig, C. D. (2024). Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Twenty-seventh edition. Retrieved from http://www.ethnologue.com

Lepri, L., & Vitali, D. (2009). Dizionario Bolognese-Italiano Italiano-Bolognese Dizionèri Bulgnaiṡ-Itagliàn Itagliàn-Bulgnaiṡ. Bologna: Pendragon.

Saunders, G. (1984). The expression of number in Bolognese nouns and adjectives: a morphological analysis. Romanitas: Studies in Romance Linguistics, 213-244.

Vitali, D. (2008). Per un’analisi diacronica del bolognese: Storia di un dialetto al centro dell’Emilia-Romagna. Ianua. Revista Philologica Romanica Vol. 8, 19-44.