College of Humanities

46 Postmodern Influences on Women’s Political Weaponization of Personal Style in the United States, 1960-1980

Krystan Morrison and Brandon Render

Faculty Mentor: Brandon James Render (History, University of Utah)

Abstract

Fashion and style were essential to the ways that women both promoted and supported long lost ideals of sexual freedom, political autonomy, and social equality during the second wave feminist movement. Postmodern interpretations of society that arose in art, academia, and activism around this time influenced the way that clothing was used as a political tool by social agitators in the latter half of the twentieth century. Concepts of sign value and symbolized identity proposed by French Sociologist Jean Baudrillard along with newly developed epistemological structures likes Patricia Hill Collins’ Black Feminist Epistemology established academic frameworks which aided the development of activist movements that utilized these and other approaches. Postmodernism in artistic spaces also urged creators to undermine hierarchical structures such as the distinction between historically fine arts and “lesser crafts,” which made fashion design and consequently fashion consumption a valuable medium for displaying artistic expression. Certain displays of style used by feminists in the second wave movement include the mini skirt, black women’s use of soul style and “styling out,” and intentionally disruptive displays of androgyny from predominantly black and queer women. These fashion choices established a visual social identity for the second wave movement that was appealing to millions of women in America, whicheffectively furthered the sociopolitical agenda of those social agitators involved in calls for liberation.

Introduction

Despite nationally gaining the right to vote in 1920, political power and individual autonomy of most American women remained severely limited in the early 1900s. Wartime labor necessity introduced thousands of women to the workforce in the years between the world wars, but equal opportunity with men remained essentially nonexistent.International conflicts throughout the first half of the twentieth century occupied the attention of United States citizenswhich stalled widespread calls for equal rights among men and women until the conclusion of World War II. Around this time, postmodern interpretations of knowledge and behavior began to emerge in academic, artistic, and activist spaces. These interpretations encouraged subscribers to question previously accepted narratives, epistemologies, and traditions in their respective fields. Many postmodernists strove to subvert hierarchical societal relationships,undermined existing power structures, and rejected the idea of a fundamental objective truth or reality. Resulting frameworks that were popularized by contemporary scholars allowed women and queer communities in the 1960s onward to challenge longstanding patriarchal institutions and reject gendered expectations. Style and dress were particularly important to the ways in which women and queer communities used postmodern philosophies to resist oppression and destabilize social hierarchies in the latter half of the twentieth century.

Fashion and personal style played a central role in American women’s approach to social conflicts centered around political equality in the late twentieth century. Despite this, historical literature largely avoids centering self-expression through dress in conversations revolving around liberation movements that began in the 1960s. Much focus is dedicated to social organizing in the form of literature, congregation, and ideology, but organization in the form of self-representation by second wave feminists is often overlooked. As Isabelle Duff puts it, “the neglect of study in women’s appearance in the past is a serious neglect among historians of the study of women’s culture.”1 This paper argues thatboth postmodern theory and personal style played a fundamental role in the shaping and success of social movements in the 1960s, especially those involved in calls for women’s liberation.

Historical Background

Many first wave feminists were not unaware of the oppression posed by traditional clothing standards. Conservative dress practices had historically reinforced political and social adversity faced by women and queer communities for thousands of years, and deviation from societal norms often carried extreme consequences. Thus, women typically found it necessary to comply with societal demands by expressing acceptable feminine presentation.2What first wave feminists did not fully grasp was the widespread awareness of symbolism and its sociopolitical importance proposed by subsequent postmodern thinkers. Reconceptualizing style and dress as prideful expressions ofpersonal freedom allowed second wave feminists to effectively achieve a greater sense of bodily autonomy and political freedom than their predecessors in the second half of the twentieth century. Postmodern interpretations of gender, race, and class were critical to style and design choices that intentionally subverted expected presentations of each as a response to greater political conflicts.

Beyond imposing a loss of free will, clothing standards imposed physical restrictions on women and limited their behavior since long before the formation of the United States. A realization of clothing’s role in subjugation resulted in several women adopting androgynous attire ranging from Turkish trousers to boyish bloomers in the latter half of the 19th century. Early feminists who adopted these styles included Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Angela Grimké. Others like Lucretia Mott and Martha C. Wright avoided conversion due to perceivedunattractiveness or religious prohibition of these styles.3 Plenty of these women knew that their clothing choices would have social consequences and went to great lengths to avoid unnecessary negative attention. In fact, several early feminists denied the close connection between distinct deference from tradition and desires for political equality, citing instead factors such ashealth and safety concerns or increased mobility as the primary motivator behind wardrobe changes. As a result, new styles like bloomers and trousers were seen by audiences as more of a comedic spectacle than a political statement.4 Of course, cited health concerns and desires for mobility were warranted, but the undefined political meaning and scattered justifications behind early feminist styles ultimately thwarted the popularity and political effectiveness of these women’s responses to societal marginalization.

First wave feminism also ignored experiences unique to women of varying class, race, and ethnicity among other social factors, which made genuine unity and acceptance seem a far out ideal moving into the 1900s. Racially discriminatory first wave feminists impeded on the organizational flow and solidarity in and among social movements ultimately resulting in less effective demands for equality altogether. While some women like Susan B. Anthonyrejected feminine beauty standards and dress practices, other notably black feminists recognized that feminization could be an effective strategy to reclaim womanhood that they were so often denied. Early feminist Ida B. Wells details her frequent sacrifice of financial stability for the illusion of social importance through dress in her personal pocket diary. “I am very sorry I did not resist the impulse to buy that cloak; I would have been $15 richer,” she laments.5 Wells’s entry reveals that Black feminists in the 19th century often reclaimed traditionally feminine practices at the expense of other forms of social power to combat the masculinization and social silencing of black women in American society.

Furthermore, Sojourner Truth famously used evangelical ideals which included embracing feminine qualities as a way that black women could shake racist masculine stereotypes and usher in societal acceptance. Although a black feminist framework had not yet been developed, Sojourner Truth’s logic appealed to many black first wave feminists “because she called attention to the intersection of race and gender.”6 The effectiveness of different forms of social expression was dependent upon clear distinctions of social acceptability, leaving many black women with little to gain and a lot to lose from de-feminized personal presentations that were advocated for by white feminists in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Of course, incremental advancements were still made in women’s presentation of personal style. These advancements are evident of the growing desire among women in the 20th century to achieve a greater sense of personal freedom and social respect in American society. Chief among trendy wardrobe changes were flapper styles of the 1920s and masculine trousers popularized by working women during World War II, with a brief return to conservatism characterizing styles of the 1930s in between. Androgyny and unexpected gender presentation were often evident in these style trends, but it was not expressly tied to the desire for political freedom or civic equality. Instead, notions of patriotic duty and civic obligation were used as justification for style changes of the 1940s. This encouraged feminists to examine the non-reciprocal relationship between women and the United States government whereby women’s labor was often extracted from them with little to no compensation in the form of civil liberties or personal freedoms. Some women during the flapper era and riveters from World War II engaged the same excuses of mobility,safety, and health concerns that were evoked by first wave feminists, though a great deal more were beginning to realize the freedom and opportunity that androgynous self-presentation presented them during the war alongside employment and educational opportunities. Women’s critical importance to the at-home effort during World War II coupled with the many other social freedoms they experienced urged female citizens to reevaluate their deemed place in the social order and promote postmodern interpretations of society that stressed equality among men and women instead of accepting ascribed subordination.

An interest in aesthetic and sign value as opposed to status and utility showcases a shift brought on after World War II by postmodern interpretations of art and society which critiqued practices including dress that supported existing social hierarchies like racism, sexism, and classism. The failed reception of trousers and bloomers in late 19thcentury feminist calls for freedom compared to sweeping style changes of the 1960s illustrates how the popularization of postmodern theories was necessary to allow artists and consumers to tie style, dress, and design effectively and explicitly to political action and agenda less than one century later. Moreover, epistemological transitions brought on by postmodernism in the 1960s allowed black women to uniquely redefine themselves and their demands throughpersonal style and clothing choices in ways that first wave feminists were not able to do. These unique presentations of personal expression effectively furthered the sociopolitical agendas and ideologies promoted by American feminists in the second half of the 20th century.

Research

Historians widely recognize the cultural significance of fashion trends in the United States during the 1960s. However, this cultural significance is scarcely linked to postmodern interpretations of society and behavior that emerged contemporaneously. Scholars like Andreas Huyssen, however, recognize the historical relationship between postmodern thought, cultural signifiers, and political conflict that erupted in the mid-1900s. Moreover, the weaponization of fashion as a social tool in this period is largely glossed over by political historians, seen as secondaryto vocal demands for freedom. Historian Isabelle Shaw explains, “while fashion may appear to be trivial, it is essential to look at the history of fashion in terms of how it inspired women to create broader movements of women’s liberation.” Other historians including Betty Luther Hillman and Isabelle Duff seek to defend the importance of personal style and self-expression by detailing the effectiveness of women’s reliance on symbolic representations of bodily autonomy and political freedom. This paper argues that due to the popularization of postmodern thought and practice in the 1960s, social agitators involved in calls for women’s liberation and other political aims routinely utilized the signatory nature of fashion to challenge longstanding hierarchical institutions and ideologies that perpetuated oppressive relationships among men and women in American society.

The widespread emergence of postmodernism marked a period in history where a variety of practices, ideologies, and institutions were challenged on the basis that there is no objective truth, knowledge, or way of being. Although early postmodernists arose in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the movement was popularized in the mid 20th century due to the horrific aftermath of World War II and other global conflicts. Shocked by the culmination of international conflict and increased globalization which introduced westerners to new forms of culture and knowledge, postmodernists questioned “fundamental” concepts of each, allowing new and forgotten interpretations of human behavior and interaction to take center stage. “The occupation of France, the siege of Leningrad, the bombings of London, Dresden, and Tokyo, the mass murders in the concentration camps, and the detonation of atom bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” argue scholars Joseph Kermin and Gary Tomlinson, “…all were virtually impossible for human beings (including artists) to take in. History seemed to be showing that all human conceptions of the world wereinadequate.”7 The confusion caused by global conflicts urged many theorists and ordinary citizens to pursue actionwhich examined alternative ways of existing and behaving that were not promoted by modern society. Reigning institutions and ideologies were constantly challenged as society moved to accept postmodern interpretationsof knowledge and practice. Postmodern thought particularly infiltrated artistic, academic, and activist spaces.

Several postmodern theorists were obsessed with the study and observation of the subject and identity. Sociologist Jean Baudrillard, for example, helped popularize the idea that individuals often use material objects such as clothing to symbolize implied identity (e.g, personality traits, value systems, religious beliefs). He goes even further to argue that the symbolization of specific identities can become more important than characteristics of the impliedidentity itself to both the individual and their audience.8 This point of view suggests that clothing and other material items are extremely important signifiers of social positioning. It also likely influenced the way clothing was produced, consumed, and displayed by social actors and political groups beginning in the late 1960s. As women fought to gain more independence and opportunity in the United States, many utilized postmodern concepts of identity in settings ranging from casual to professional as a means to subvert oppressive traditions and gendered norms. Fashion design and personal style were central to these women’s attempts at reclaiming autonomy and disturbing the status quo during second and third wave feminist movements.

One strategy included explicitly connecting clothing to personal or political expression through theories of sign value and constructed identity popularized by postmodern theorists like Baudrillard.

Amid growing calls for greater independence and civic equality among women from diverse backgrounds, thousands gradually recognized the importance of displaying personal expression and political opinion through style and dress habits as a way of reinforcing larger societal demands for autonomy and subverting traditional race and gender hierarchies. Many women in the mid 1900s described traditional clothing standards as oppressive and unnecessary, though some neglected to recognize the transformative power of self-presentation as a political tool. In The Clothes IWear Help Me to Know My Own Power, Betty Luther Hillman argues, “While not all feminists cut their hair or rejected feminine beauty culture, the politicization of hairstyles, dress, and self-presentation became central to the cultural politics of the second wave feminist movement…”9 In other words, the politics of personal style played an undeniably critical role in women’s fight for bodily autonomy and equal opportunity during social movements of the 1960s and ‘70s.

Postmodernists also typically rejected the idea of one objective truth or reality. Consequently, the works of many postmodernists revolve around alternative, forgotten and newly developed epistemological structures that relied upon nontraditional methods. One such academic is social theorist Patricia Hill Collins, whose work posited that intersecting forms of hierarchical oppression come together to compose unique identities and diverse realities for different people. Specifically, Collins examined the way that race and gender come together as separate forces to form experiences of oppression unique to black women. Her research based on theories of intersectionality as well as nontraditional research methods such as qualitative interviews developed by black women in the late 20th century came to be known as Black Feminist Epistemology (BFE). Features of Collins’ epistemological method were developed by Black feminists throughout America who were simultaneously involved in calls for Black power and women’s liberation throughout the 1960s and into later decades. One unique feature of BFE was incorporation of the concept of intersectionality, a term coined by American activist and academic Kimberle Crenshaw in her essay titled “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Policies.” Crenshaw explains, “Because the intersectional experience is greater than the sum of racism and sexism, any analysis that does not take intersectionality into account cannot sufficiently addressthe particular manner in which Black women are subordinated.”10 The theory of intersectionality has since been used to understand oppressive experiences unique to Latina women and queer identities among others. Notions of intersectionality and the fight for civil rights among women from separate social classes is reflected in the ways that Black women’s style diverged from their Caucasian counterparts in the 1960s and 70s. Unique demands for freedom required unique displays of socialpositioning from black women that articulated their personal wants and needs. Less organized forms of resistance toprevailing power structures from black women included the notion of “styling out,” while organizations such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee expressly outlined the importance of garments like denim overalls to their sociopolitical agendas.11 Black women’s distinct deviation from styles and clothing worn by white feminists in the 1960s showcases the uniquely simultaneous demands for sexual freedom and racial equality that marginalized postmodern feminists urged during this period.

Promotion of alternative knowledge and practice in existing areas expectedly transformed art and literature. Theconnection of art to mass culture and politics through postmodern interpretations of society allowed creators and audiences to explore new creative outlets and unique political strategies in areas including historically lesser arts like garment design. In After the Great Divide, Andreas Huyssen explores how postmodern thinking that emerged after World War II challenged prevailing modernist interpretations of art and rejected “the necessary separation of high art from mass culture, politics, and the everyday.”12 Postmodern interpretations of art blurred distinctions between artistic and political expression in luxury and emerging mass markets which allowed a wider audience to engage in unique personal expression through clothing consumption and design.

Consequently, the postmodern art movement of the 1950s and 60s allowed designers and public audiences to view fashion as not only a necessary utility, but as an innovative artform. Scholar Llewellyn Negrin reveals that around the mid-1900s, artists began to question the hierarchies of art production and subverted practical notions of utility by emphasizing a balance between the useful and the aesthetic. Garment design was a key trade in which notably earlier artists like William Morris and contemporary designers like Rei Kawakubo worked to fundamentally change perceptions of fashion design in artistic spaces.13 The slow acceptance of fashion into the art world allowed designers and consumers to explore more creative and artistic functions of fashion that had previously been neglected due to rigid social constraints. Along with this, growing queer communities in American cities began using the expressive nature of fashion to directly display sexual and gender orientation in public spaces despite the condemnation of homosexuality and ‘gender regression’ in many parts of the United States. The use of clothing as a political tool which encouraged self-expression and personal freedom by gay and transgender people was directly related to—if not completely centered upon— showcasing their complex identities through material objects in ways outlined by theorists like Baudrillard.

The popularization of postmodern concepts like sign value, identity, and fashion as art allowed a variety of sociopolitical movements to be defined largely by aesthetics of individual activists who pioneered issues that prioritized women’s liberation. Even those uninvolved in active and vocal demands for freedom who engaged styles utilized by specific social groups came to be associated with these groups themselves. Baudrillard explains, “never again will the real have to be produced. This is the vital function of the model in a system of death… A hyperreal henceforth sheltered from the imaginary, and from any distinction between the real and the imaginary, leaving room only for the orbital recurrence of models and the simulated generation of difference.” In other words, social symbols speak for themselves and those who engage them. 14 The symbolic representation of reality (in this case, protesting the oppression of women in American society through style) overcomes the importance of reality (the hypothetical lack of involvement in social conflicts from the subject displaying the social symbol). Thus, even those who unconsciously participated in style trends worn by activists propelled social causes bysymbolically associating themselves with the movement which conveyed solidarity in the minds of others. Activists, however, purposefully engaged signatory properties of clothing in strategies aimed at dismantling oppressive structures.

The mini skirt was an infamous example of clothing’s political sign value during the 1960s and 70s. Mini skirts, along with other scantily clad garments like the bikini, were worn by American women and around the globe as a way of reclaiming sexual power and bodily autonomy. Furthermore, black feminists supporting the Civil Rights Movement in the United States during the 1960s and 70s used fashion and uniform to subvert acceptability politics in black communities as well as promote equal rights among men and women through carefully crafted androgyny. Lesbians and queer communities also advocated androgyny and self-presentation as central to wider calls for political freedom and social acceptance. These strategies and fashion trends of the 1960s and 70s exemplify the close connection between clothing, political conflict, and contemporaneous postmodern theories due to their reliance on postmodern interpretations of behavior and resistance. The convergence of these concepts allowed feminists to establish political freedom more effectively in America than ever before.

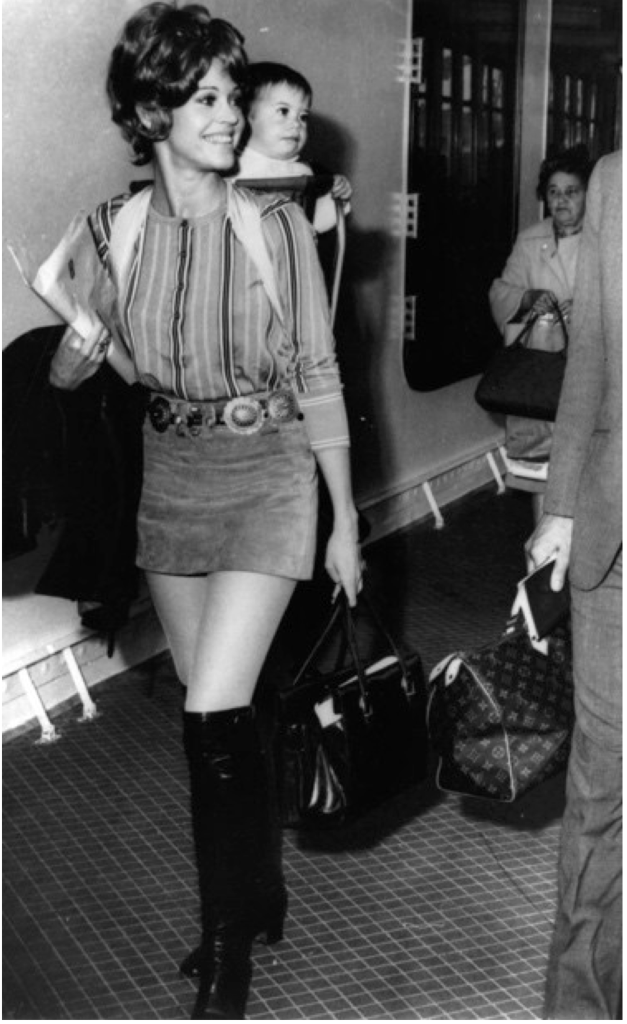

Mary Quant is commonly credited with the invention of the miniskirt: a garment notoriously viewed as a symbol used by activists of the late 20th century to embolden calls for women’s liberation and bodily autonomy. She enthusiastically recognized her contribution to challenges aimed at prevailing social structures which upheld patriarchy and subjugated femininity, and “enjoyed adapting minimal styles which subverted traditional social and gender roles.”15Quant undeniably introduced the miniskirt to rebellious western audiences who were eager to express styles separate from older generations which showcased individual autonomy. Miniskirts allowed women to casually confront longstanding traditions of gender presentation, sexual repression, and motherhood expected by patriarchal western societies, ultimately establishing bodily autonomy and personal freedom as central to personal wardrobe choices. Along withother societal advancements like The Pill and abortion rights established in 1974 by the U.S. Supreme Court, miniskirts supported long lost ideals of sexual freedom and domestic liberation for women across America; unlike the former revolutionary developments, the miniskirt was a visual representation of the political power that each woman had gained within American society which constantly reminded audiences of feminism’s success and popularity.

American Actress and Activist Jane Fonda and daughter in Le Havre, France, 1969.16

Quant’s claim to the invention of the mini skirt is disputed, however. Globalization and the rise of cross cultural connection most likely allowed designers around the globe to take inspiration from their peers resulting in numerous interpretations of significant innovative silhouettes in the 1960s.

Other scholars like Tanisha C. Ford point to women in Tanzania as the original inspiration of “minis,” and credits sources like Drum Magazine, a South African publication aimed at black readers, with popularizing the revolutionary style in the 1960s.17 Regardless of who is credited with the design, creative and sociopolitical intent remains the same: the use of clothing to send a social or political message became a primary means by which disenfranchised communities could voice opinions or circumvent notions of acceptability in the status quo. Women across the globe conveniently used the mini skirt as a form of sexual freedom and reclamation of bodily autonomy which strongly supported global calls for women’s liberation in the 1960s and following decades.

Widespread acceptance and adoption of this style was not a coincidence. The global popularity of the miniskirt suggests, “…there was a willingness from young women to defend their choices, which illustrates the conviction they held in the decisions they made, and their desire for these choices to be accepted by society,” historian Isabelle Duff argues in The Morality of the Miniskirt. “Fashion, long held in the domain of women, was a tool for liberation.”18Simply put, women’s wardrobe choices in the 1960s were not merely trends based on desirability or acceptance, but intentionally disruptive displays of personal power and opposition to outdated world views. The inherent social meaning ascribed to the mini skirt attracted many feminist consumers who relied on its sign value as a means ofvisually establishing a contrarian identity within patriarchal American culture. Consequently, the style was dominant in depictions of the second wave feminist movement. The process whereby feminists purposefully positioned themselves in contradiction to western expectations is not unlike the process described by Baudrillard by which material objects are used to establish identity of the self.

Furthermore, the re-imagination of style and dress as politically transformative and beneficial to calls for freedom allowed second wave feminists to successfully engage postmodern frameworks which related to subverting societal power dynamics and systemic oppression.

Similar to the way that many American feminists saw the mini skirt as universal symbol of sexual liberation, they often saw demands and experiences of middle-class white women as central to all demands for women’s liberation and explanations of patriarchy. Third wave feminist Judith Butler explains, “The urgency of feminism to establish a universal status for patriarchy in order to strengthen the appearance of feminism’s own claims to be representative has occasionally motivated the shortcut to a categorial or fictive universality of the structure of domination, held to produce women’s common subjugated experience.”19 The idea that relatively privileged women’s experiences defined the totality of patriarchy and sexism was, of course, not true, and feminists engaged in work that examined intersectionality recognized the need to represent black and queer feminists demands in a particular way that showcased experiences different than or contrary to those of white feminists. The Combahee River Collective’s A Black Feminist Statement published in 1977 reads: “A Black feminist presence has evolved most obviously in connection with the second wave of the American women’s movement beginning in the late 1960s. Black, other Third World, and working women have been involved in the feminist movement from its start, but both outside reactionary forces and racism and elitism withinthe movement itself have served to obscure our participation.”20 For this reason, many second wave feminists who felt unrecognized by the mainstream movement mainly organized by and for white women opted instead for communities, actions, and demands which embraced intersectionality and upheld historically marginalized voices moving into the late 1970s.

Representations of race and gender through personal style by Black women in America during the 1960s and 70s not only represents a promotion of postmodern understanding of the subject and identity in relation to material objects, but a clear understanding of intersecting identities and the subjectivity of reality proposed by postmodern theorists likePatricia Hill Collins who emerged out of this era of political conflict and social uprising. Black feminists were actively aware of the false objectivity present in white feminist narratives of sexism and patriarchy that were popularized during the 60s. As aresult, many strove to construct knowledges and understandings that prioritized the lived reality of black women andother minorities in an attempt to ameliorate the exclusion of black women from feminist spaces and society altogether. The re-imagination of black feminist spaces follows societal trends of postmodern thought and behavior that subverted traditional social structures and sought to establish innovative understandings of modern society.

One way that intersectional feminists made their unique demands easily recognizable was by using personal style and political expression through dress. Black feminists across the United States frequently utilized style and dress to subvert notions of blackness, acceptability, and womanhood during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. Generalized trends like “soul style” and “styling out” coupled with more specific dress tendencies like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s denim uniform allowed Black Americans to use fashion as an immediate means of sociopolitical self-expression throughout the 1960s. Black women particularly used these fashion trends to culturally align themselves and reclaim social power within American society. Styling decisions not only came to symbolize Black Power in the minds of nonaligned citizens but encouraged those supporting the movement to adopt certain characteristics of style as a show of solidarity to the movement.

‘Soul Style’ was characterized by the Americanization of African aesthetics by Black citizens who strove to showcase a cultural connection to diasporas in Africa during the Black Power Movement.21 This style was a transformative way for Black women (and men) to subtly participate in sociopolitical conversations alongside direct calls for equal rights and protected citizenship. Historian Tanisha C. Ford outlines the importance of soul style to the BlackPower Movement and calls for civil rights in the 1960s; her 2015 book Liberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and theGlobal Politics of Soul explores how personal style was purposefully used as a means of promoting political agendas and subverting conservative notions of blackness and acceptability in South Africa, the United States, and the United Kingdom by activists and ordinary citizens alike. Ford explains, “[Angela] Davis did not ignore the fact that natural hairstyles and African inspired clothing were fashionable in the black power era. She contextualized her style within a larger international history in which Africana women incorporated the concept of “styling-out,” or dressing fashionably, into the quest for black freedom and gender equality.”22 From this perspective, the expression of personal pride through style and dress manifested not primarily through fine materials or expensive products, but in cultural connections to personal heritage and solidarity with liberating social movements.

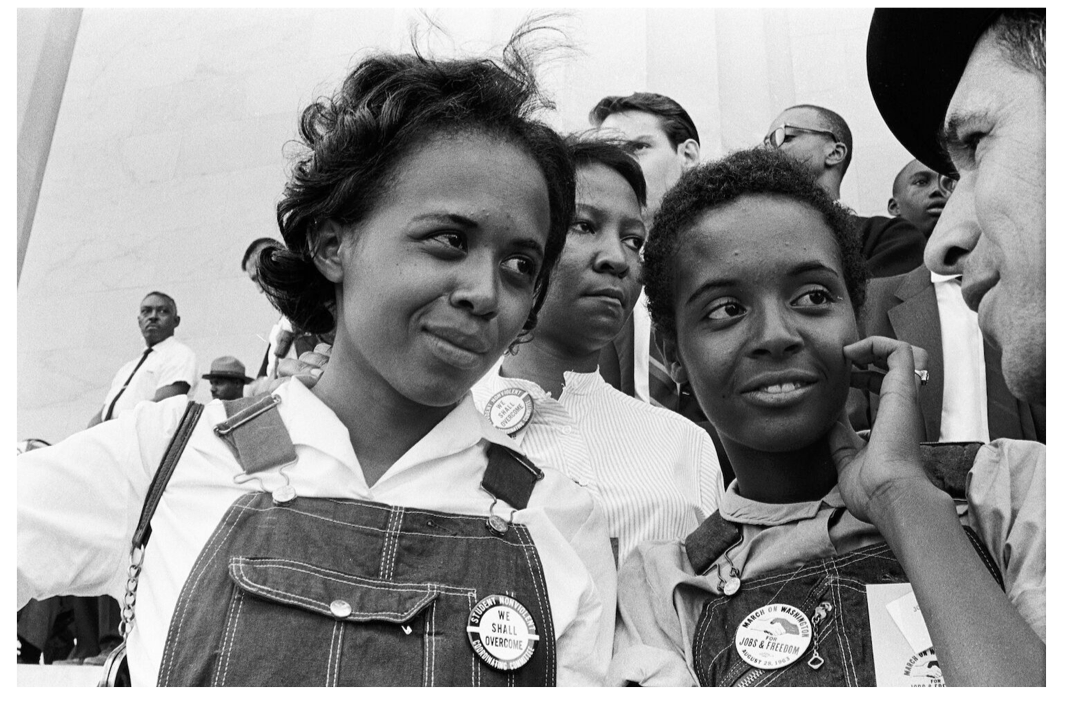

American Activists Dorie Ladner and sister Joyce Ladner atthe 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.23

The use of uniformity by social groups to express a political standing during the call for black freedom in the 1960s was particularly effective in garnering support for the movement. One group that successfully used uniforms as a supportive tool in their sociopolitical agenda was the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, an activist group committed to non-violent protests against the obstruction of black civil liberties. SNCC was heavily involved in campaigns such as the Freedom Rides in the summer of 1961 which encouraged black voter registration and the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Organizations like SNCC purposefully used clothing such as denim overalls to visually align themselves with middle class Americans and appeal to wider audiences who could potentially relate to the group’s calls for freedom, especially among women.

While the SNCC uniform was used to appeal to working Americans of any gender, Ford suggests, “denim overalls in particular provided an androgynous self-representation that reinforced women’s political aims…The women used the uniform to consciously transgress a black middle-class worldview that marginalized certain types of women and particular displays of blackness and black culture.”24 This represents a shift among black women in the acceptable presentation of femininity which abandons those tactics that rely on gendered expectations long used by their feminist foremothers. SNCC women keenly recognized the necessity of androgynous self-representation in the fight for political power under patriarchy, and personal style’s intimate connection to the quest for bodily autonomy and equal opportunity. The SNCC uniform silently presented a message of its own that supported the vocal demands of black feminists involved in the Civil Rights Movement which strengthened solidarity within the movement and vocal calls for freedom.

Androgynous self-representation was also used by queer feminists as a means of deconstructing traditional interpretations of gender identity and sexual orientation that were promoted by patriarchal standards in American society and regularly protected by local or state law. Queer activists involved in rebellions like the Stonewall Riots of 1969 recognized the transformative power of clothing and self-expression in the fight for political representation and social equality. In fact, clothing and personal style were central to the cause of the uprising wherein steadfast lesbians revolted against constant harassment of queer residents from New York City’s Greenwich Village and state restrictions on expressive freedom through the New York State Gender Appropriate Clothing Statute established in the 19th century.

In The Stonewall Riots: A Documentary History, historian Marc Stein explores how a “consumer’s republic” had come to define American social life in the second half of the twentieth century, and “gay Americans increasingly demanded the same rights to consume that others took for granted or fought to exercise.”25 I agree with Stein’s assertion that queer communities accurately recognized the connection between limited social participation, economic exclusion, and political oppression, though his analysis lacks focus on of the consumption of clothing and composition of personal style which was integral leading up to political conflicts involving queer communities and structural forces which condemned the promotion of homosexuality or ‘gender regression’. Clothing and style were central to structural justifications for the oppression of queer communities in the United States, and outdated laws centered around gender expression were often evoked as a way to limit visual expressions of queerness. Conversely, clothing was a primary tool used by gay Americans to reclaim the ‘rights to consume’ outlined by Stein; the visual representation of gender expression through clothing and style, like contemporaneous women’s movements, insisted on bodily autonomy and personal freedom not despite—but because of—historical limitations placed on dress in these communities. Style was intentionally integrated into the quest for political freedom among queer activists in order to ensure social visibility and material resistance to longstanding oppressive forces that were subverted by political activists and postmodern scholars beginning in the 1960s.

In the context of Stonewall, the legal justification for oppression of queer expression rested in a New York State Criminal Statute commonly known as the “three article law.” As the nickname suggests, the statute required that citizens be wearing at least three articles of gender appropriate clothing in public or otherwise risk arrest. An account from former Stonewall employee Harry Beard reveals that one ofthe first arrests in what culminated to be the Stonewall Riots relied on this statute as justification for harassment of a lesbian patron of the Stonewall Inn. “Arrested for not wearing three pieces of clothing correct for her gender according to New York law, she was handcuffed…There is no doubt that, furious for whatever reason, she put up a fight.”26Several supporting sources cited by David Carter in Stonewall: the Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution insist that this event is what initially provoked violent outbursts from queer Greenwich Village residents.27 Clothing and personal style not only advertised implicational symbols which supported free self-expression, but laid expressly in the middle of sociopolitical conflicts involving queer communities and oppressive power structures including the infamous Stonewall Riots of 1969.

Like other liberatory movements in this period, queer communities fighting for representation used postmodern concepts of subject, identity, and art in their organizations of political activism and demands for civic equality. Theinterconnectedness between identity and personal style for people like butch lesbians, trans women and trans men among others echoes theories proposed by Baudrillard which suggest that separation between identity and objects that represent identity is essentially nonexistent in postmodern society. Beyond this, historical repression of queer identities makes the symbolic representation of identity almost necessary to establish concrete resistance to traditional or oppressive functions of heterosexist society which reinforce more broad discriminatory practices like economic and social exclusion. Gender based representation laws remained intact in New York until the beginning of the 21st century, but clear opposition to these repressive laws manifested in trends which represented sexual freedom and styles adopted by queer individuals that eventually helped establish widespread support for gay rights in America.

Conclusion

Frameworks provided by postmodern interpretations of culture, society, and behavior provided second wave feminists with the ideological framework and praxis necessary to effectively weaponize clothing as a political tool inthe 1960s. In earlier decades, feminists often neglected to explicitly align wardrobe choices with political aims or refused to deviate from traditional gender expectations altogether. Because of this, attempts to androgenize women’s fashion in the late 19th and early 20th century were not effective in garnering social support for women’s liberation and equality and were in fact often counterintuitive. It wasn’t until the development and popularization of postmodern thought and practice that American women defined appearance and personal style as a signifier or extension of personal identity in response to oppressive traditions upheld by modernity. The rise of postmodern thinking and practice gave voice to alternative modes of operation in several areas of society, and postmodern theorists questioned basic assumptions behind commonly held beliefs that structured society. Resulting literature from sociologists like Baudrillard and Collins supported widespread societal discoveries of sign value, intersectionality, and power dynamics that characterized the postmodern movement. These concepts were used by both activists and ordinary citizens to bolster calls for political liberation among women, people of color, and queer communities in American society.

Specifically, American women utilized the sign value associated with certain displays of personal style and self-expression to effectively support calls for independence, autonomy, and equality. Articles like the mini skirt and SNCC’s denim overalls consequentially became symbolically representative of demands for freedom, and popularizednontraditional representations of feminine and black identities. Articulations of gender expression through personal style were central to the ways in which queer communities contradicted traditional notions of acceptability that were upheld by outdated legal, social, and moral justifications. Furthermore, persistent stylistic choices among women and queer people in the 1960s and 70s which reflected desires for personal freedom and individual autonomy opened opportunities of expression to generations of independent beneficiaries who came afterwards. Recognizing the importance of style and dress to women’s history allows historians to uncover cultural connections to politics, economy, and social life regarding women that might otherwise have gone unnoticed in numbered reports, statistical analyses, and logistical reasoning that is commonly proposed by traditional historians. Furthermore, an insistence on the importance of clothing to women’s political desires and successes shows how women and other activists often used self-expression as a political tool in and of itself, contrary to the idea proposed by many historiansthat personal style was not central to demands for freedom. To this day, the effects of postmodern theory including theuse of clothing as a sociopolitical tool are enjoyed by 21st century American women and queer communities who regularly exercise dress practices that were promoted by second wave feminists and sexual liberationists in the second half of the 20th century.

Notes

1 Isabelle Duff, “The Morality of the Miniskirt” in Trinity Women’s Review, (Vol. 1 No. 1 2017), 23.

2 Betty Luther Hillman, “‘The Clothes I Wear Help Me to Know My Own Power’: The Politics of Gender Presentation in the Era of Women’s Liberation.” in Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies (Vol. 34 No. 2, 2013), 155–85.

3 Robert E. Riegel. “Women’s Clothes and Women’s Rights” in American Quarterly, (Vol. 15 No. 3, 1963), 390-401.

4 Riegel, 394.

5 Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Ida B. Wells pocket diary, 1885-1887. University of Chicago Library Special Collections Research Center.

6 Ula Taylor, “The Historical Evolution of Black Feminist Theory and Praxis” in Journal of Black Studies,

(Vol. 29, No. 2 1998), 236.

7Joseph Kermin and Gary Tomlinson, “Chapter 23: The Late Twentieth Century” in Listen 10th Edition

(New York: W. W. Norton & Company 2019), 368.

8 Jean Baudrillard, “The Non-Functional System, or Subjective Discourse” in The System of Objects, trans. James Benedict, (London: Verso 1996, originally published 1968), 4-17.

9 Hillman, “The Politics of Gender Presentation”, 155.

10 Kimberle Crenshaw, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine,Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Policies” in University of Chicago Legal Forym: Vol. 1989, No. 1., 140.

11 Tanisha C. Ford, Liberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of Soul, (University of North Carolina Press 2015), 3.

12Andreas Huyssen, “The Hidden Dialectic: Avant Garde—Technology—Mass Culture” in After The Great Divide: Modernism, Mass Culture, Postmodernism, (Indiana University Press 1987), 10.

13 Negrin, Llewelyn. “Fashion as Art or Art as Fashion?” In Fashion: Tyranny and Revelation by Damayanthie Eluwawalage, (Boston: Brill, 2019), 261-270.

14 Baudrillard, “The Nonfunctional System”, 3.

15Mary Quant Exhibition, Victoria & Albert Museum, South Kensington, 2019.

16 Central Press. Fonda and Child, STF/AFP/Getty Images, 1969.

17 Ford, Liberated Threads, 164-174.

18 Duff, “Morality of the Miniskirt”, p. 26.

19 Judith Butler, “Subjects of Sex/Gender/Desire” in Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, (New York: Routledge, 2006), 6.

20 Combahee River Collective, “A Black Feminist Statement”, in The Second Wave: A Reader in Feminist Theory by Linda Nicholson, (New York: Routledge 1997), 63-70. Originally published in 1977.

21 Ford, Liberated Threads.

22 Ford, p. 3.

23 Danny Lyon, SNCC (2020), (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2020), photo originally taken in 1963.

24 Ford, Liberated Threads, 84.

25 Marc Stein, “Part II: Stonewall” in The Stonewall Riots: A Documentary History, p. 151.

26 David Carter, “’We’re Taking the Place!’” in Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution

27 Carter, 145-158.

Bibliography

Baudrillard, Jean. “The Non-Functional System, or Subjective Discourse” in The System of Objects. Originally published in 1968. Translated by James Benedict. London: Verso. 1996.

Butler, Judith. “Subjects of Sex/Gender/Desire” in Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge. 1990. pp. 1-44. ISBN: 0-203-90275-0.

Carter, David. “’We’re Taking the Place!’” in Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution. New York: St. Martin’s Press. 2004. pp. 149-158. ISBN: 0-312-20025-0 Central Press. Fondaand Child. Hulton Archive. STF/AFP/Getty Images. 1969.

Combahee River Collective. “A Black Feminist Statement” in The Second Wave: A Reader in Feminist Theory.Edited by Linda Nicholson. New York: Routledge. 1997. pp. 63-70. ISBN: 978-0-415-91761-2.

Crenshaw, Kimberle. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Policies” in University of Chicago Legal Forum. Vol. 1989, Iss. 1, Article 8. 139-167.

Duff, Isabelle. “The Morality of the Miniskirt” in Trinity Women’s Review, Vol. 1 No. 1. Dublin: Trinity College Dublin. 2017). pp. 23-34.

Ford, Tanisha C. Liberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of Soul. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. 2015.

Hillman, Betty Luther. “’The Clothes I Wear Help Me to Know My Own Power’: The Politics of Gender Presentationin the Era of Women’s Liberation” in Frontiers: A Journal of Women’s Studies, Vol. 34 No. 2 (2013). pp. 155-185. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5250/fronjwomestud.34.2.0155.

Huyssen, Andreas. “The Hidden Dialectic: Avant Garde—Technology—Mass Culture” in After the Great Divide:Modernism, Mass Culture, Postmodernism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press 1987. pp. 3-15.

Kermin, Joseph and Gary Tomlinson. “Chapter 23: The Late Twentieth Century” in Listen 10th Edition. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 2019. pp. 368-388. ISBN: 978-1-324-03944- 0.

Lyon, Danny. SNCC (2020). New York: Whitney Museum of American Art. 2020. https://whitney.org/events/sncc-oct-29

Riegel, Robert E. “Women’s Clothes and Women’s Rights” in American Quarterly, Vol. 15 No. 3. 1963. pp. 390-401.

Stein, Marc. “Part II: Stonewall” in The Stonewall Riots: A Documentary History, New York: New York University Press. 2019. pp. 126-185. ISBN: 978-1-479-85828-6.

Taylor, Ula. “The Historical Evolution of Black Feminist Theory and Praxis” in Journal of Black Studies, Vol. 29 No. 2.1998. pp. 234-253. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2668091.

V&A Kensington. Mary Quant Exhibition. London: Victoria and Albert Museum South Kensington. 2019.

Wells-Barnett, Ida B. Ida B. Wells pocket diary, 1885-1887. Chicago: University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center. https://blackwomenssuffrage.dp.la/collections/ida-b- wells/ibwells-0009-008