College of Social and Behavioral Science

163 The Impact of the Thrive Program on Youth Well-Being

Abigail McDonald; Marissa Diener; Alexander Becraft; and Mitchell Wulfman

Faculty Mentor: Marissa Lynn Diener (Family & Consumer Studies, University of Utah)

Mental health is a growing issue among the youth in Utah. The SHARP survey analyzes prevention needs across the state of Utah for students in grades 6, 8, 10, and 12. The SHARP (Student Health and RiskPrevention) survey is a statewide survey given every 2 years to students in most public and some charter schools across Utah. The purpose of this survey is to determine the amount of substance use and antisocial behavior present in adolescent populations as well as determine the risk and protective factors that predict these behaviors (Utah Department of Health and Human Services, 2021). This includes issues with mental and physical health, gang involvement, and academics. The results from the 2023 SHARP survey showed that thepercentage of Utah youth with moderate and high needs for mental health treatment are high and have continued to increase each year. Sixty-seven percent of youth surveyed showed moderate depressive symptoms and ten percent showed high depressive symptoms. Eighteen percent had seriously considered suicide in the past 12 months, and seven percent indicated they had attempted suicide. Twenty percent felt isolated from others.The results of this survey show the growing need of mental health intervention and prevention programs in Utah. The present study evaluates the effectiveness of a program called Thrive to improve mental health outcomes in youth.

The Thrive Program

The Thrive program is based on cognitive behavioral therapy, socioemotional learning, and positive psychology. Cognitive behavioral therapy or CBT is used to identify and change dysfunctional feelings or thoughts and situations that might trigger them. Patients learn to modify and cope with these thoughts and feelings. A study looking at the effect of CBT on children and adolescents with anxiety found that CBT increases post-treatment remission in anxiety compared to those who did not receive treatment (James et al., 2020). CBT has been proven to be an effective form of treatment which is why it was integrated into the Thrive program.

Socioemotional learning is also integrated into the Thrive Program. Socioemotional leaning is an educational method that encourages the learner to develop and employ social and emotional skills such as self-awareness, social-awareness, and decision-making skills. As adolescents develop, they are challenged in a number of ways. Having the appropriate skills to be able to adapt socially and emotionally is very important for their well-being. One study that looked at social emotional learning programs found that there was asignificantly positive effect on the participants. The largest effects were found in self-awareness and social awareness. There was also a decrease in psychosocial health problems in students who participated (van deSande et al., 2019). It is important for children to be able to adapt socially and emotionally as they develop.These skills are a crucial part of one’s happiness and well-being.

Positive psychology is a fundamental part of the Thrive program. Positive psychology focuses on positive behaviors, feelings, and emotions. The goal is to promote one’s well-being and happiness. A meta-analysis of 51 positive psychology interventions found that they significantly improved participants’ mental health and well-being and decreased depressive symptoms (Sin et al., 2009).

Another meta-analysis focused specifically on the effects of school-based positive psychology in adolescents. This study focused on youth between the ages of 10 to 18 years old. The duration of the programs lasted anywhere from 4 to 30 weeks. Similar to the previous meta-analysis, they concluded that these interventions enhanced well-being and reduced depression symptoms. They also found that those effects stayed significant in the long run (Tejada-Gallardo et al., 2020). The Thrive Program also aims to support student’s well-being and mental health as they develop. Thrive offers this in a group-based program where adolescents are encouraged to support one another. Lessons are designed for the students to be able to make connections to their own life and apply the skills they are learning. It is clear that positive psychology interventions in schools improve overall well-being in adolescents.

The Thrive Program is adapted from a similar program called WeBeWell which focuses on adults, specifically college students. Thrive is 6 weeks long. It is an out-of-school program that the youth can sign up for. Participants are placed into groups based on their age that meet virtually once a week for an hour. Each week has a different topic that facilitators lead the group on. Topics include gratitude, strengths, goals, relationships, restructuring negative thinking patterns, and mindfulness and meditation. Other resources on the weekly topics are also sent out to the participants and their parents at the beginning of the week. Participants have the opportunity to share their own experiences and apply the lessons to their own lives. Thrive aims to determine the impact of the program on participants’ depression, anxiety, and well-being.

Both WeBeWell and Thrive were adapted from a program called ENHANCE which stands for Enduring Happiness and Continued Self-Enhancement. (Heintzelman et al., 2020) The ENHANCE program is a 12-week long program for adults. In a randomized controlled trial of ENHANCE, participants completed pre and postassessments to determine the success of the program. One group of participants took part in in-person group therapy while another group did the same program but online. The goal of ENHANCE was to improve participants overall well-being, happiness, and life satisfaction. Studies found that the program did significantly improve well-being, happiness, and life satisfaction as well as decrease negative mental health symptoms. Thrive is similar to ENHANCE in that it is a program that aims to benefit the well-being of its participants. Thrive differs in that it is a shorter program, it is strictly online, and it works with adolescents.

There are many other programs that aim to improve the mental health and wellbeing of their participants. One example is the Maytiv positive psychology school program. This program is based in Israel and focuses on students in middle school. Teachers are trained based on positive psychology curriculum and incorporate it intothe classroom. The program consists of stories, exercises, discussions, writing, and then action. They found that students in the program had increases in peer relations, emotional engagement, GPA, and school engagement (Shoshani et al., 2016). Thrive works with a similar age group and is also influenced by positive psychology. Thrive differs from the Maytiv program in that it is not connected to school, participants are in smaller groups with 2-3 facilitators, and there are different topics for each of the 6 weeks.

Current Study

How did the Thrive program impact youth well-being?

Method

Procedure

Upon enrollment, participants completed a pretest. After completing the Thrive program, they completed a post test. These tests consisted of well-being, depression, and anxiety measures.

Participants received an $80.00 stipend for completing the program. In order to complete, they needed to take the pre and post tests and attend 5 out of the 6 of the weekly groups. The Thrive evaluation received IRB approval.

Participants

Participants were recruited through schools, youth organizations, and Latinos in Action. They were all in middle school with 49 girls and 38 boys.

Measures

Well-being was measured using the Youth Quality of Life Instrument (Salum et al., 2012).

This survey includes 15 items and uses a rating scale where participants were asked to rank how much they relate to each statement on a scale of zero to ten. Zero being not at all and ten being very much. Participants took this survey both before and after the Thrive 6-week program in order to determine whether their quality of life improved. Some examples of statements from this survey are, “I feel good about myself” and “I feel safe when I am at home”. The 15 items were summed to create an overall composite score. Internal reliability was found to be highly reliable for both the pre (a=0.92) and post (a=0.92) surveys.

Anxiety symptoms were measured using the GAD-7 (Spitzer et al., 2006). This survey is used to determine the level of anxiety that participants experience both before and after participating in the Thrive program. The survey is made up of 7 prompts which determine how often participants experience symptoms. The responses rank from zero to three. Zero meaning not at all, 1 is several days, 2 is more than half the days, and 3 is nearly every day. This is used as both a pre and post survey. Internal reliability was found to be highly reliable for both the pre (a=0.84) and post (a=0.83) surveys. Depression was measured using the CES-10 scale (Andresen et al., 1994). This survey consists of 10 statements that participants rated on a 4-point scale. The lowest meaning rarely or none of the time and the highest meaning all of the time. The score from the survey is a sum of the 10 items. Two items were reverse scored. Statements from the survey included, “I was bothered by things that usually don’t bother me” and “I felt lonely”. The internal reliability for the depression scale was found to be adequate for pre (a=0.73) and post (a=0.71) surveys.

Results

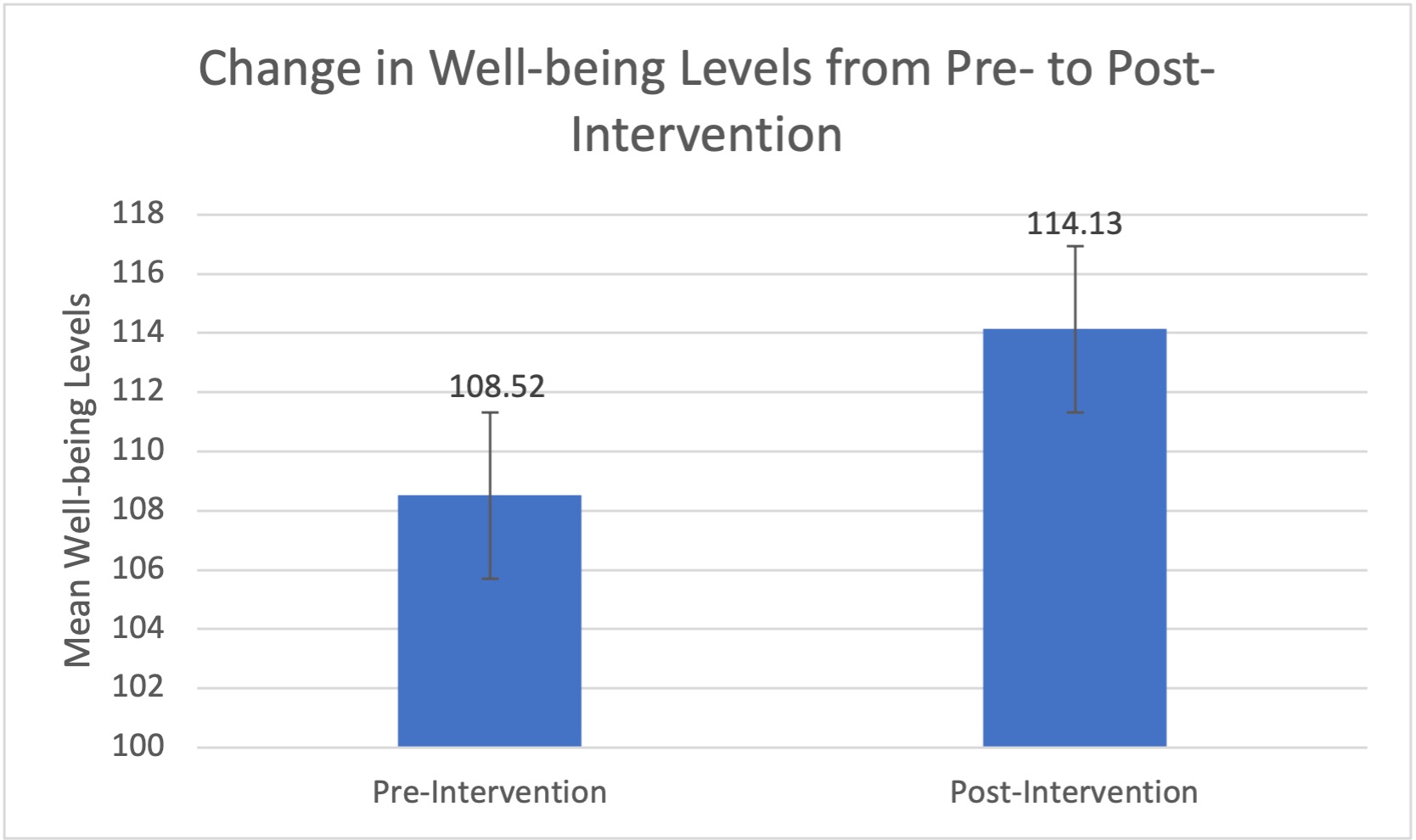

T tests were used to examine whether mean levels of depression, anxiety, and quality of life differed over the course of the study. The participant’s wellbeing pre scores (M=108.52, SD=24.73) and post scores(M=114.13, SD=24.32) show an increase in wellbeing over the course of the program. t (115) =-3.095, p=.002.

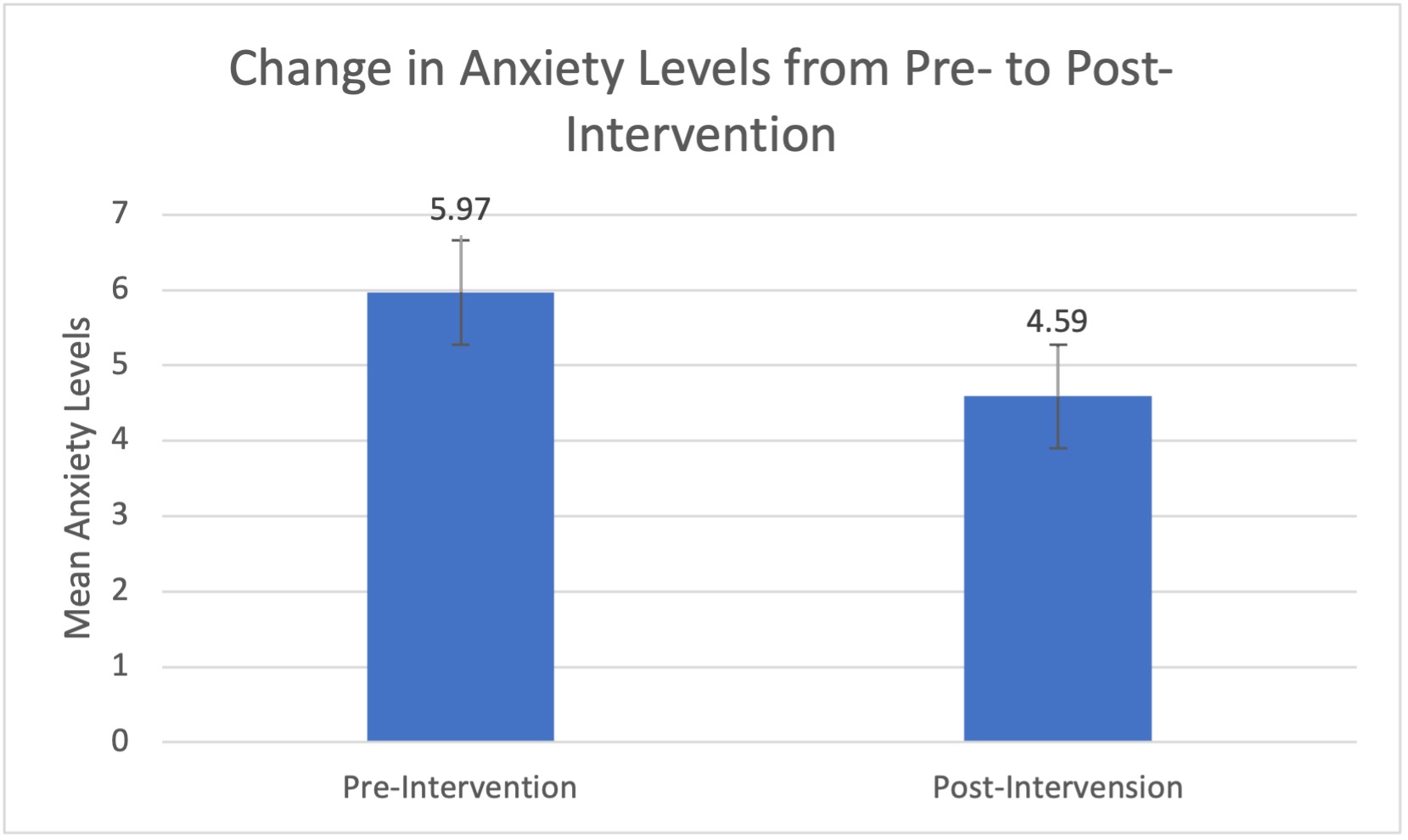

There was a significant decrease from participant’s anxiety pre scores (M=5.97, SD=4.51), to their post scores (M=4.59, SD=3.97), indicating a decrease in anxiety. t (115) = 3.87, p< .001

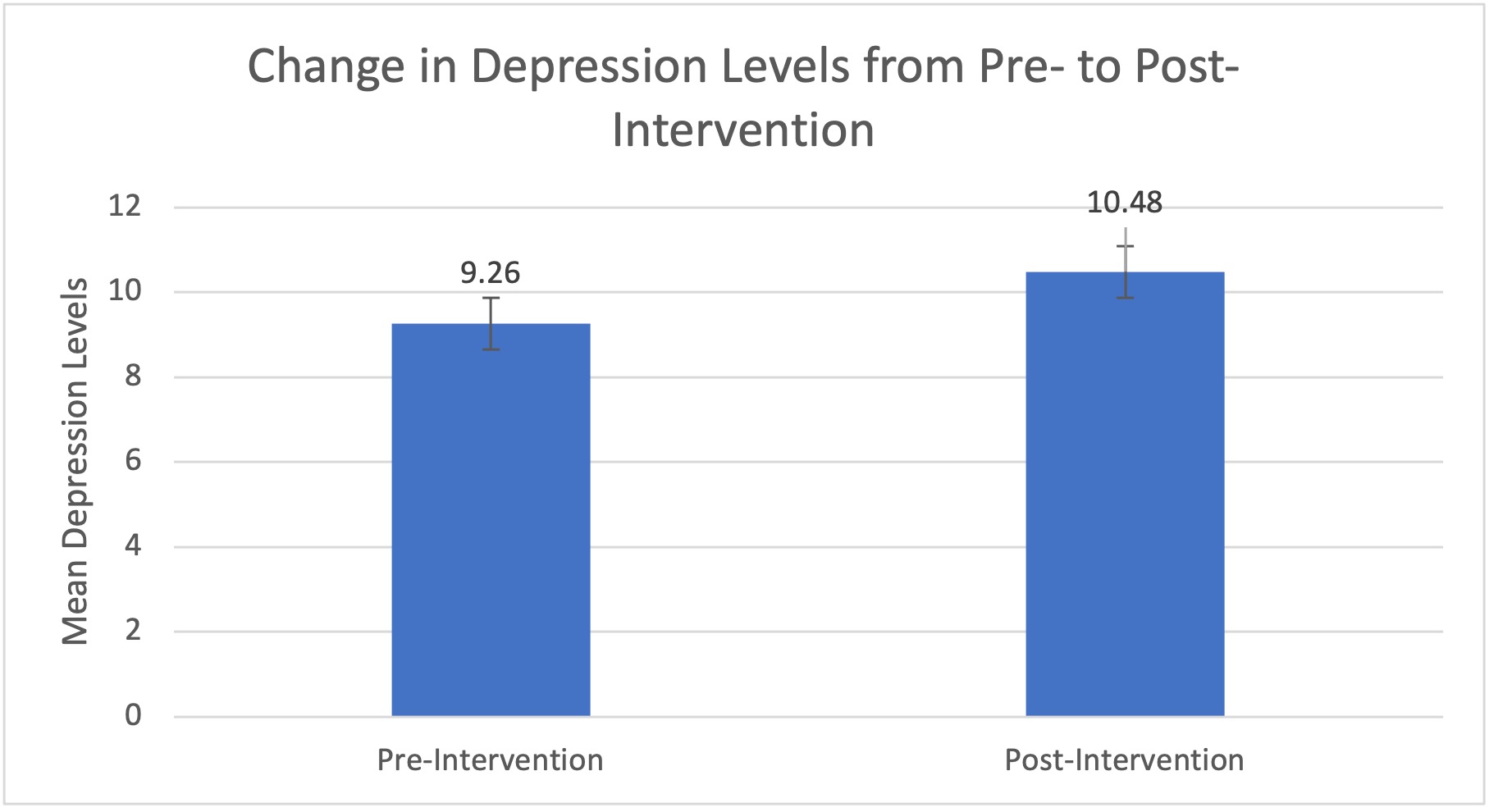

The results from the depression survey pre-test (M = 9.26, SD = 4.81) and post-test (M = 10.48, SD = 3.4) indicate that the participant depression scores went up., t (115) = -2.87, p = .005.

Discussion

Anxiety and quality of life improved over the course of the program. These findings are in line with theMaytiv and Heintzelman studies. Out-of-school programs are so important in supporting youth mental health After just 6 weeks of the Thrive Program, participants experienced less symptoms of anxiety and increased well-being.

We don’t understand the depression finding. We haven’t seen an increase in our high school or collegedata. We plan to replicate that with another set of data. The increase could be due to depression going up over the course of the academic calendar or the participants being more willing to be open about their depression symptoms. There could also be a selection effect where parents encouraged the program for youth who were previously showing depression symptoms.

This research is preliminary, and our research is ongoing. The Thrive program has expanded since the collection of the data in this study. We hope to continue growing as a program and addressing the mental health and well-being of adolescents.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by WeBeWell, Live Like Sam, and Schmidt Futures. Special thanks to Marissa Diener, Alexander Becraft, and Mitchell Wulfman for their guidance and knowledge as well as the participants.

The principal investigator of this study, Alexander Becraft, and researcher, Mitchell Wulfman, are both executives of the WeBeWell organization and, as a result, have a conflict of interest. The University of Utah’s Conflict of Interest Office and the Institutional Review Board have reviewed and managed these conflicts of interest.”

References

Andresen, E. M., Malmgren, J. A., Carter, W. B., & Patrick, D. L. (1994). Center for Epidemiological Studies Short Depression Scale (CESD-10) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t10141-000

Heintzelman, S., Kushlev, K., Lutes, L. D., Wirtz, D., Kanippayoor, J. M., Leitner,D., Oishi, S., & Diener, E. (2020). ENHANCE: Evidence for the Efficacy of a Comprehensive Intervention Program to Promote Subjective Well-Being. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Applied, 26(2), 360–383. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000254

James, A., Soler, A., & Weatherall, R. (2020). Cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013162.pub2

Salum GA, Patrick DL, Isolan LR, Manfro GG, Fleck MP. (2012). Youth Quality of Life Instrument- Research version (YQOL-R): psychometric properties in a community sample, J Pediatr, 88(5), 443-448.

Sin, N. L., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2009). Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice-friendly meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(5), 467–487. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20593

Student Health And Risk Prevention: Prevention Needs Assessment Survey. (2021). State of Utah Department of Human Services: Division of Substance Abuse and Mental Health.https://dsamhtraining.utah.gov/_documents/SHARPreports/2021/StateofUtahProfileRep ort.pdf

Shoshani, A., Steinmetz, S., & Kanat-Maymon, Y. (2016). Effects of the maytiv positive psychology school program on early adolescents’ well-being, engagement, and achievement. Journal of School Psychology, 57, 73–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2016.05.003

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2006). Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t02591-000

Tejada-Gallardo, C., Blasco-Belled, A., Torrelles-Nadal, C., & Alsinet, C. (2020). Effects of school- based multicomponent positive psychology interventions on well-being and distress in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(10), 1943–1960. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01289-9

van de Sande, M. C., Fekkes, M., Kocken, P. L., Diekstra, R. F., Reis, R., & Gravesteijn, C. (2019). Do universal social and emotional learning programs for secondary school students enhance the competencies they address? A systematic review. Psychology in the Schools, 56(10), 1545– 1567. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22307